Abstract

Purpose

Little is known regarding the links between mental disorder and lost income in low- and middle-income countries. The purpose of this study was to investigate the association between mental disorder and lost income in the first nationally representative psychiatric epidemiology survey in South Africa.

Methods

A probability sample of South African adults was administered the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview schedule to assess the presence of mental disorders as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, version IV.

Results

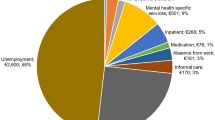

The presence of severe depression or anxiety disorders was associated with a significant reduction in earnings in the previous 12 months among both employed and unemployed South African adults (p = 0.0043). In simulations of costs to individuals, the mean estimated lost income associated with severe depression and anxiety disorders was $4,798 per adult per year, after adjustment for age, gender, substance abuse, education, marital status, and household size. Projections of total annual cost to South Africans living with these disorders in lost earnings, extrapolated from the sample, were $3.6 billion. These data indicate either that mental illness has a major economic impact, through the effect of disability and stigma on earnings, or that people in lower income groups are at increased risk of mental illness. The indirect costs of severe depression and anxiety disorders stand in stark contrast with the direct costs of treatment in South Africa, as illustrated by annual government spending on mental health services, amounting to an estimated $59 million for adults.

Conclusions

The findings of this study support the economic argument for investing in mental health care as a means of mitigating indirect costs of mental illness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The cost of mental illness is complex and difficult to measure. Yet, it is an important indicator of the economic burden of mental illness to a society. Traditionally, cost of mental illness studies has been divided into direct and indirect costs [1]. Indirect costs tend to outweigh direct costs in most studies [1]. Among indirect costs, the cost of lost income due to mental illness is an important element.

According to Amartya Sen, economic development needs to take into account not only the basket of goods (such as income and assets) that a person holds but also the relevant personal characteristics that govern how the primary goods are converted into the person’s ability to promote her or his ends [2]. For example, a person who is disabled may have a larger basket of primary goods but be less able to lead a normal life, or pursue her or his objectives, than another person with a smaller basket of primary goods. Mental health enters this framework as a set of “functionings” that enable the various things a person may value doing or being: “a person’s “capability” refers to the alternative combinations of functionings that are feasible for her to achieve” [2] (p.75). Taken together, mental health and income provide a basis for optimizing choice in the consumption of goods and services, as well as pursuit of valued life choices.

Mental disorders lead to lost income through the disabilities and stigma with which they are associated [3] and negatively influence a person’s ability to convert available income into capability—both key elements in the social selection or social drift pathway in the cycle of poverty and mental illness [4]. Conversely, low income increases the risk for mental disorders through increased risk of adverse life events and reduced access to resources that can buffer the effects of those life events—contributing to the social causation of mental illness [5]. A recent study from the United Kingdom has provided evidence of both social causation and social selection in the long-term predictors of adult depression and anxiety disorders [6].

Most studies showing an association between mental disorders and reduced income have been conducted in high-income countries [1, 7]. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), little is known regarding the links between mental disorder and reduced income, despite evidence of a substantial burden of mental illness [8, 9] and severely under-resourced mental health care systems [10, 11]. Studies have been conducted of indirect costs of mental illness in Taiwan [12] and Kenya [13], but both of these have adopted a human capital approach, which focuses on estimates of lost productivity, rather than reported lost income. Losses in income or paid production are particularly threatening (in terms of impoverishment) in low- and middle-income settings where compensation mechanisms such as welfare or disability benefits for mental illness are unavailable or limited.

Data regarding mental illness and lost income can provide estimates of some of the indirect economic costs of mental illness to these societies and strengthen the economic argument for investment in mental health care as a means of mitigating these costs and promoting more broad-based economic development. This is particularly pertinent in the light of emerging evidence from LMICs that providing mental health care can reduce disability and yield economic benefits to individuals and their households [14]. This study sets out to report on the association between mental disorder and lost income in the first nationally representative psychiatric epidemiology study in South Africa.

Methods

The South African Stress and Health (SASH) Study is a national survey of mental health conducted between January 2002 and June 2004. The study rationale, methods, and ethics approval have been described in detail previously [15, 16]. A probability sample of 4,351 South African adults (age ≥ 18 years) living in both households and hostel quarters was selected using a three-stage design. The response rate was 85.5 %, and individuals of all major racial and ethnic groups were included. The sample was weighted to ensure representation of each of the main ethnic groups [15]. All analyses employed person-level weights to account for the complex survey design, with adjustments for sample selection, non-response, and post-stratification factors as previously described. Calculations for estimation and inference were based on the Taylor series linearization method.

The World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI) [17] was used to assess the presence of mental disorders as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, version IV (DSM-IV) [18]. The CIDI is a fully structured diagnostic interview that is lay administered and can generate diagnoses according to both the WHO International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) and the DSM-IV diagnostic systems. The translation of the English version of CIDI into the six other South African languages used in the SASH study was carried out according to WHO recommendations of iterative back-translation conducted by panels of bilingual and multilingual experts. Discrepancies found in the back-translation were resolved by consensus of an expert panel.

The mental disorders assessed in the SASH study were anxiety disorders [panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)], mood disorders (major depressive disorder, dysthymia), substance disorders (alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse, drug dependence), and intermittent explosive disorder. DSM-IV organic exclusion rules and diagnostic hierarchy rules were applied to all diagnoses, except in the case of substance use disorders where abuse was defined with or without dependence. Disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar mood disorder were not included in the SASH survey, as these disorders would require a clinical assessment, and the available resources for the study were only able to support lay administered instruments such as the CIDI.

In the analysis of lost income, only severe depression and anxiety disorders were included. Respondents were included if they (a) satisfied the criteria for any of the following disorders in the previous 12 months: major depressive episode, agoraphobia, PTSD, GAD, social phobia, specific phobia, intermittent explosive disorder, adult separation anxiety, and dysthymia and (b) either attempted suicide in the past 12 months or had a high level of impairment in the social, family, occupational, or study domains.

All respondents were asked to report their personal earnings in the past 12 months, before taxes. Respondents were instructed to count only wages and other stipends from employment, not pensions, investments, or other financial assistances or income (such as grants).

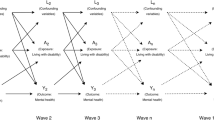

Analysis followed the same approach as that of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication in the United States of America [7]. Multiple regression analysis was conducted of 12-month personal earnings on those with DSM-IV mental disorders, controlling for age, gender, substance abuse, education, marital status, and household size. Projections of total annual cost to South Africa in lost earnings were extrapolated from the sample by multiplying the lost earnings per individual with severe depression or anxiety disorders by the prevalence of these disorders and the total population. We used generalized linear regression models to examine the associations between severe depression and anxiety disorders (as the independent variable) with different measures of lost income (as dependent variables). First, we examined 12-month earnings as a continuous variable, modeled with a logarithmic link function and normal error distribution; the resulting coefficients can be interpreted as the mean difference in 12-month income, comparing individuals with and without severe depression and anxiety disorders. Normality was tested using standard methods (for example Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). We ran separate models for both employed and unemployed individuals and employed individuals only. In addition, we examined any income in the preceding 12 months as a binary-dependent variable, modeled with a logit function; the resulting odds ratios can be interpreted as the relative odds of reporting any income in the preceding 12 months for individuals with and without severe depression and anxiety disorders. All models were adjusted for participant sex, age, alcohol dependence (12 months), alcohol abuse without dependence (12 months), drug dependence (12 months), drug abuse without dependence (12 months), alcohol dependence (lifetime), alcohol abuse without dependence (lifetime), drug dependence (lifetime), and drug abuse without dependence (lifetime).

All recruitment, consent, and field procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of the University of Michigan, Harvard Medical School, and by a single project assurance of compliance from the Medical University of South Africa that was approved by the National Institute of Mental Health. The research conforms to the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

In the sample as a whole, major depressive disorder, agoraphobia, and alcohol abuse were the most prevalent DSM-IV disorders. Anxiety disorders were the most prevalent group of disorders, followed by substance use disorders. The number of people from whom data on lost earnings were collected was 4,074, comprising 2,436 women and 1,638 men. The prevalence estimates were 3.3 % for severe 12-month depression and anxiety disorders, 10.1 % for all other (non-severe) 12-month disorders, and 10.1 % for other lifetime disorders (Table 1). There were significant gender differences in the prevalence of these disorders (p < 0.05). There were also significant gender differences in all substance use disorders (p < 0.05), with the exception of 12-month drug dependence. Only 37.7 % of the sample reported any earnings in the previous 12 months. Significantly more men had any earnings in the previous 12 months than women (p < 0.05).

The presence of severe mental disorder was associated with a significant loss of income in the previous 12 months among South African adults (Table 2). In Model 1 (employed and unemployed), severe depression and anxiety disorders were associated with reduced income for the entire sample, including both employed and unemployed groups (p = 0.0043). In Model 2, severe depression and anxiety disorders were not associated with the presence of income (p = 0.99). In Model 3, severe depression and anxiety disorders were associated with reduced earnings among employed people only (p = 0.0063).

In simulations of costs to individuals, the mean estimated impact of severe depression and anxiety disorders was $4,798 per person, after adjustment for age, gender, substance abuse, education, marital status, and household size (Table 3). This impact was felt more acutely by women, among whom the mean estimated lost earnings associated with severe depression and anxiety disorders was $6,390 compared as $1,313 in men. Projections of total annual cost in lost earnings for South Africans with these disorders, extrapolated from the sample, are $3,626,666,995, assuming estimated lost earnings due to individuals with severe depression and anxiety disorders of $4,798, 12-month prevalence of 3.25 %, and the South African adult population (20–64 years) of 23,257,556 based on the 2001 South African census [19].

Discussion

The findings of this study draw attention to the strong association between lost income and severe depression and anxiety disorders in South Africa. The total economic burden of mental illness is likely to be higher than that reported in this study, given the exclusion from this analysis of child and adolescent mental disorders and other severe chronic disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar mood disorder. In separate analysis, child and adolescent mental disorders in the SASH survey were associated with reduced educational attainment and likely subsequent income [20]. Furthermore, the study does not take into account either direct economic costs of mental illness, such as those associated with treatment or other indirect costs such as transport to health facilities, lost income among caregivers, and disability grants. The hidden costs to carer and family members are particularly important and frequently difficult to assess [21].

The findings in relation to gender are particularly striking. Women are at increased risk for depression and anxiety disorders, showing a 12-month prevalence approximately twice that of men, in keeping with international studies [8]. In addition, the impact of these disorders on women’s income is much greater than it is for men. This difference may be partially attributed to increased prevalence but may also be due to the more disabling impact of these disorders in women, or the possibility that women may be earning income in more unstable informal settings, which are more vulnerable to losses of income associated with illness.

The findings support other research that indicates that mental illness, through its strong association with reduced earnings, appears to have a major socio-economic impact on LMICs. For example, previous studies from LMICs, although using a human capital approach to measuring indirect costs, indicate a loss of productivity due to depression of $1,053 million in Taiwan [12] and a loss of productivity due to 5,678 admissions to psychiatric hospitals of $2,569,719 in Kenya during the 1998/1999 financial year [13]. The findings are also supported by other data from South Africa [22, 23] and Brazil, Chile, Uganda, and Zimbabwe [24–27] that indicate an association between socio-economic adversity and increased risk for mental illness. However, the dearth of longitudinal studies in LMICs means that it is difficult to draw any clear conclusions regarding causality, from our current knowledge base. There is also a strong possibility that the associations in this study reflect the increasing vulnerability to depression and anxiety disorders among low-income groups in South Africa, described elsewhere as the social causation of mental illness [3].

The indirect costs of severe depression and anxiety disorders stand in stark contrast with the direct costs in South Africa, as illustrated by government spending on mental health services. In 2005, this was estimated to be 1, 5, and 8 % of total health expenditure in Northern Cape, North West, and Mpumalanga provinces, respectively [28]. Projected to the total South African adult population [19], this amounts to annual government expenditure of $59,325,103—a figure which is dwarfed by the estimated lost earnings of $3,626,666,995 among adults with severe depression and anxiety disorders alone. Although there are limitations to comparisons of this nature (treatment does not necessarily lead to full recovery of lost earnings), such data do provide support for the argument that it costs South African society more to not treat than to treat mental illness. This adds support to the economic argument for preventing mental illness [29] and scaling up mental health care and rehabilitation services [14, 30], as a means of mitigating the economic burden of these illnesses.

There are several limitations to this study which need to be noted. As acknowledged previously, there are limitations to the SASH study in the validity of the instrumentation and its applicability to all of the cultural groups in South Africa [16, 31]. This analysis of lost income has been conducted only for adults with severe depression and anxiety disorders and does not take into consideration the lost earnings among adults with mild to moderate mental illness, children, and adolescents with any disorders or adults with other severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar mood disorder. Furthermore, the study is cross-sectional, making it difficult to draw conclusions regarding the causal relationship between lost income and depression/anxiety disorders, a feature which is shared among many epidemiological studies that examine socio-economic correlates of mental ill-health in LMICs [32]. Thus, the association noted here may be attributable to either social causation (those with lower income are at greater risk of depression and anxiety disorders) or to social selection (those with depression and anxiety disorders are at greater risk of losing income through increased health expenditure, job loss and reduced productivity associated with the increased disability and stigma of their conditions). Finally, one cannot conclude that the lost income associated with mental illness is a broader societal loss. For example, the wages that are not paid to people with depression and anxiety disorders may be used to employ other previously unemployed people and may not lead to a decrease in consumption and the implication that there is a broader economic loss.

Future research needs to address some of these limitations by conducting longitudinal studies in LMICs, examining the effects of interventions on the relationship between socio-economic factors and mental illness [14], and exploring the impact of mild–moderate mental disorders on income and production.

References

Hu T (2006) An international review of the national cost estimates of mental illness, 1990–2003. J Ment Health Policy Econ 9:3–13

Sen A (1999) Development as freedom. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Saraceno B, Itzhak L, Kohn R (2005) The public mental health significance of research on socio-economic factors in schizophrenia and major depression. World Psychiatry 4:181–185

Dohrenwend BP, Levav I, Shrout PE et al (1992) Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders: the causation-selection issue. Science 255:946–952

Aneshensel CS (2009) Toward explaining mental health disparities. J Health Soc Behav 50:377–394

Stansfeld S, Clark C, Rodgers B et al (2011) Repeated exposure to socioeconomic disadvantage and health selection as life course pathways to mid-life depressive and anxiety disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46:549–558

Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, Lakoma MD et al (2008) Individual and societal effects of mental disorders on earnings in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Am J Psychiatry 165:703–711

Kessler RC, Ustun TB (2008) The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: global perspectives on the epidemiology of mental disorders. Cambridge University Press, New York

Lopez DA, Mathers DC, Ezzati M et al (2006) Global burden of disease and risk factors. Oxford University Press and The World Bank, New York

Jacob KS, Sharan P, Mirza I et al (2007) Mental health systems in countries: where are we now? Lancet 370:1061–1077

Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M et al (2007) Resources for mental health:scarcity, inequity and inefficiency. Lancet 370:878–889

Yeh LL, Yue CL, Ming-Chin Y et al (1999) The economic cost of severely mentally ill patients. Chin. J Ment Health 1–15

Kirigia JM, Sambo LG (2003) Cost of mental and behavioural disorders in Kenya. Ann Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2:1–7

Lund C, De Silva M, Plagerson S et al (2011) Poverty and mental disorders: breaking the cycle in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 378:1502–1514

Williams DR, Herman A, Kessler RC et al (2004) The South Africa Stress and Health Study: rationale and design. Metab Brain Dis 19:135–147

Williams DR, Herman A, Stein DJ et al (2007) Prevalence, service use and demographic correlates of 12-month psychiatric disorders in South Africa: the South African stress and Health Study. Psychol Med 38:211–220

Kessler RC, Ustun TB (2004) The World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative version of the WHO-CIDI. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 13:95–121

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC

Statistics South Africa: Census (2001) Pretoria, Statistics South Africa. http://www.statssa.gov.za/census01/HTML/default.asp 2003

Myer L, Stein DJ, Jackson PB et al (2009) Impact of common mental disorders during childhood and adolescence on secondary school completion. S Afr Med J 99:354–356

Das J, Do QT, Friedman J et al (2009) Mental health patterns and consequences: results from survey data in five developing countries. World Bank Econ Rev 23:31–55

Bhagwanjee A, Parekh A, Paruk Z et al (1998) Prevalence of minor psychiatric disorders in an adult African rural community in South Africa. Psychol Med 28:1137–1147

Robertson BA, Ensink K, Parry CD et al (1999) Performance of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3) in an informal settlement area in South Africa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:1156–1164

Kinyanda E, Woodburn P, Tugumisirize J et al (2011) Poverty, life events and the risk for depression in Uganda. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46:35–44

Abas M, Broadhead J (1997) Depression and anxiety among women in an urban setting in Zimbabwe. Psychol Med 27:59–71

Almeida-Filho N, Lessa I, Maghalaes L et al (2004) Social inequality and depressive disorders in Bahia, Brazil: interactions of gender, ethnicity, and social class. Soc Sci Med 59:1339–1353

Araya R, Lewis G, Rojas G et al (2003) Education and income: which is more important for mental health? J Epidemiol Community Health 57:501–505

Lund C, Kleintjes S, Kakuma R et al (2009) Public sector mental health systems in South Africa: inter-provincial comparisons and policy implications. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 10.1007/s00127-009-0078-5

WHO (2004) Prevention of mental disorders: effective interventions and policy options, Geneva

Lancet Global Mental Health Group (2007) Scale up services for mental disorders: a call for action. Lancet 370:1241–1252

Stein DJ, Seedat S, Herman A et al (2007) Lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in South Africa. Br J Psychiatry 192(2):112–117

Patel V, Kleinman A (2003) Poverty and common mental disorders in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 81:609–615

Acknowledgments

The South African Stress and Health Study was carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the WMH staff for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and data analysis. These activities were supported by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R01-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. The South Africa Stress and Health study was funded by Grant R01-MH059575 from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of Drug Abuse with supplemental funding from the South African Department of Health and the University of Michigan. A complete list of WMH publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/. CL was funded by the Department for International Development (DfID), UK as part of the Programme for Improving Mental health care (PRIME). The opinions expressed in this paper are not necessarily those of DfID. We are grateful to the journal reviewers for their comments which have made substantive improvements to this paper.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Alan Flisher, who died tragically before the study was published.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lund, C., Myer, L., Stein, D.J. et al. Mental illness and lost income among adult South Africans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48, 845–851 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0587-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0587-5