Abstract

Background

One of the most important components of suicide prevention strategies is to target people who repeat self-harm as they are a high risk group. However, there is some evidence that the incidence of repeat self-harm is lower in Asia than in the West. The objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence of previous self-harm among a consecutive series of self-harm patients presenting to hospitals in rural Sri Lanka.

Method

Six hundred and ninety-eight self-poisoning patients presenting to medical wards at two hospitals in Sri Lanka were interviewed about their previous episodes of self-harm.

Results

Sixty-one (8.7%, 95% CI 6.7–11%) patients reported at least one previous episode of self-harm [37 (10.7%) male, 24 (6.8%) female]; only 19 (2.7%, 95% CI 1.6–4.2%) patients had made more than one previous attempt.

Conclusion

The low prevalence of previous self-harm is consistent with previous Asian research and is considerably lower than that seen in the West. Explanations for these low levels of repeat self-harm require investigation. Our data indicate that a focus on the aftercare of those who attempt suicide in Sri Lanka may have a smaller impact on suicide incidence than may be possible in the West.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Suicide is a major cause of preventable mortality throughout industrialised and non-industrialised nations [1]. More than half of the world’s suicides occur in Asia, mostly in rural communities. One key component of international suicide prevention strategies is to target individuals who self-harm as they represent an important high-risk group [2]. Around half of the people who present to hospital following self-harm in the West have previously self-harmed and around 20% repeat self-harm within 12 months of their index episode [3–6]. Risk of repetition of self-harm and later suicide is high in the West. More than 5% of the people who have attended hospital after an episode of self-harm will have died by suicide within 9 years [4].

Evidence from a number of Asian studies indicates that levels of previous self-harm amongst those who present to hospital following self-harm and who die by suicide are low. Only 17% of admissions to a tertiary hospital in urban Colombo, Sri Lanka, had a past history of self-harm [7]. Other studies from different regions of Sri Lanka report that between 1 and 26% of self-poisoning cases have previously self-harmed [8–10]. In a study carried out in southern India only 13% of suicides had previously self-harmed [11]. In Sri Lanka, a recent study found that 26% of suicides had made a previous “suicidal gesture” [12], a figure similar to that of 25% reported in a large Chinese study [13]. These findings are lower than figures of 30–47% reported in the West [14].

We have investigated the prevalence of reports of previous self-harm amongst a consecutive series of self-poisoning patients presenting to one general and one tertiary hospital in Sri Lanka.

Method

All self-poisoning patients admitted to Polonnaruwa General Hospital (July 2005 and January 2006) and to Peradeniya Teaching Hospital (November 2006–March 2007) were seen on admission by study doctors who recorded their history of previous self-harm. Both study hospitals are referral hospitals. Polonnaruwa hospital [District population is 358,984 (July 2001)] [15] serves a rural area and 60% of its poisoning admissions are transfers from other rural hospital. Peradeniya hospital [District population is 1,279,028 (July 2001)] [15] serves a more urban area; 45% of its poisoning admissions are transfers from rural hospitals, the remainder are directly admitted from the community.

Data collection

Patients were asked to recall previous episodes of self-harm (e.g. poisoning, hanging, and drowning). All conscious patients [Glasgow coma scale (GCS) > 15] were interviewed on admission soon after initial resuscitation. Patients with lower GCS scores were interviewed prior to discharge.

Validation of the responses of the study participant’s previous self-harm history was performed by cross-matching the age, gender, name, village of each study subject against previous admission recorded on the research databases for the previous 3 years in Polonnaruwa. Validation was not possible in Peradeniya as there were no research databases prior to the start of this study.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval for data collection was obtained from ethics committees of the Australian National University, Sri Lanka Medical Association, and Medical Faculties of Peradeniya and Colombo Universities.

Data analysis

Data were entered onto an excel database and analysed using Stata version 10 [16].

Results

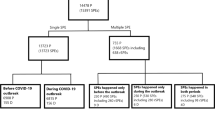

During the study period, 816 self-poisoning patients were admitted to the two study hospitals (579 to Polonnaruwa and 237 to Peradeniya). Altogether 118 (14.5%) patients were excluded from the study because data on their previous episodes of self-harm were incomplete or not recorded because of death (n = 20), transfer to other hospitals (n = 4), or oversight by the study doctors (n = 94). The patients included in the analysis (n = 698) had lower case fatality (6.1%, 95% CI 4.4–8.2%) compared to excluded patients (16.9%, 95% CI 10.6–24.9%) although the age (median age 24 vs. 25 years) and sex distributions (50.4 vs. 50.8% female) respectively of included and excluded patients were similar. Amongst the 698 included in the analysis the common methods of self-poisoning were the ingestion of pesticides [n = 313 (44.8%)], pharmaceuticals [n = 188 (26.9%)], and oleander (Thevetia peruviana) seeds [n = 119 (17.0%)]. Median length of hospital stay for our study subjects was 3 days (IQR 2–3).

Sixty-one patients (8.7%, 95% CI 6.7–11%) reported at least one previous episode of self-harm (Table 1). Levels of previous self-harm were higher in males (n = 37, 10.7%) than females (n = 24, 6.8%, p = 0.03). Subjects with a previous history of self-harm were older than those without such a history (median ages 29 vs. 23 years, p = 0.05); similar proportions of those with (45.9%) and without (44.7%) a previous episode of self-harm ingested pesticides in their index admission (χ2 = 0.03, p = 0.86).

Few patients reported more than one previous episode of self-harm: only 19 (2.7%, 95% CI 1.6–4.2%) patients had made two or more previous attempts. The proportion of patients with a past history of self-harm in Polonnaruwa hospital was lower than that of Peradeniya [36/467 (7.7%) in Polonnaruwa vs. 25/231 (10.8%) in Peradeniya (χ2 = 1.87, p = 0.17)]. Case fatality amongst those who had previously self-harmed was similar (6.6%) to those who had not previously self-harmed (6.1%) (χ2 = 0.01, p = 0.89).

Discussion

Only 8.7% of patients reported previous episodes of self-harm. This finding is consistent with a previous study from rural Sri Lanka which reported that only 8% of self-harm patients had previously self-harmed [17] and half that reported for urban Sri Lanka (17%) [7]. These figures are considerably lower than those reported in the West [3–6].

The main strengths of our study are its large size (n = 698 self-harm patients) and clinical assessment of past episodes of self-harm. However, it has a few limitations. Firstly, prospective data on repeat self-harm were not available as long-term follow-up of the study patients was not possible due to limited resources. Secondly, we relied on patient self-report of past self-harm; whilst under-reporting is possible, we found no evidence of previous episodes of self-harm from a search of the study databases in one of the hospitals. Lastly, patients who died at home or prior to transfer from rural hospital to our study hospitals were not included in our study; such patients may have a different profile of previous self-harm compared to study participants.

It is important to better understand the reasons for the low levels of repeat self-harm in rural Asia compared to the West. Possible explanations include: the high case-fatality (>5%) associated with the first episode [18], meaning high-risk patients are removed from the pool of patients at risk of repetition; different approaches to the clinical management of index episodes with low levels of mental health follow-up; and differences in the aetiology of self-harm in rural Asia. Furthermore, the longer lengths of hospital stay in Sri Lankan hospitals (average 3–4 days) [19], in part due to the greater toxicity of the substances taken in episodes of self-poisoning and decisions by some physicians to observe patient on the medical ward, may contribute because the risk of repeat self-harm is greatest in the days immediately following an index event [6] and patients are less likely to repeat self-harm whilst in hospital. In contrast, in the West, the median length of hospital stay is around 1 day and many patients who present to hospital following self-harm are not admitted [6, 20]. Thus many patients at high risk of repetition may be returned to their community and the pre-existing circumstances that surrounded their original self-poisoning within hours of their episode of self-harm.

The case fatality amongst self-poisoning patients included over the period of our study was 7.7% (63/816). This figure is considerably higher than that reported in the West (0.5–1.5%) [21, 22]; but is in keeping with previous reports from Sri Lanka [18] and other studies from developing countries in Asia [23, 24]. The higher case fatality mainly reflects the greater toxicity of the substances commonly ingested by people who self-poison in Sri Lanka (pesticides and yellow oleander) compared to those taken by self-poisoning patients in the West (analgesics and psychotropic medications).

Conclusion

These data indicate that repetition of self-harm in Sri Lanka is very low, although prospective community-based studies are needed to confirm this. Approaches to suicide prevention in rural Sri Lanka focussing on self-harm patients may therefore have limited impact on the incidence of fatal and non-fatal repeat self-harm.

References

WHO (2002) The world health report 2002. Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. WHO

Taylor SJ, Kingdom D, Jenkins R (1997) How are nations trying to prevent suicide? An analysis of national suicide prevention strategies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 95(6):457–463

Skegg K (2005) Self-harm. Lancet 366(9495):1471–1483

Owens D, Horrocks J, House A (2002) Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 181:193–199

Hawton K et al (2003) Deliberate self-harm in Oxford, 1990–2000: a time of change in patient characteristics. Psychol Med 33(6):987–995

Carter GL et al (1999) Repetition of deliberate self-poisoning in an Australian hospital-treated population. Med J Aust 170(7):307–311

De Silva D, De Alwis S, Seneviratne R (2003) Deliberate self harm (DSH) at the National Hospital Sri Lanka (NHSL): significance of psychosocial factors and psychiatric morbidity. J Ceylon Coll Physicians 36:39–42

van der Hoek W, Konradsen F (2005) Risk factors for acute pesticide poisoning in Sri Lanka. Trop Med Int Health 10(6):589–596

Ganeshamoorthy R (1985) Spectrum of acute poisoning in Jaffna—a one year survey. Jaffna Med J 1:3–12

Samaraweera S et al (2008) Completed suicide among Sinhalese in Sri Lanka: a psychological autopsy study. Suicide Life Threat Behav 38(2):221–228

Gururaj G et al (2004) Risk factors for completed suicides: a case–control study from Bangalore, India. Inj Control Saf Promot 11(3):183–191

Abeyasinghe R, Gunnell D (2008) Psychological autopsy study of suicide in three rural and semi-rural districts of Sri Lanka. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 43(4):280–285

Phillips MR et al (2002) Risk factors for suicide in China: a national case-control psychological autopsy study. Lancet 360(9347):1728–1736

Gunnell D, Frankel S (1994) Prevention of suicide: aspirations and evidence. BMJ 308(6938):1227–1233

Department of Census and Statistics, Government of Sri Lanka (2001) Census of population and housing. Sri Lanka

StataCorp (2007) Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. StataCorp LP, College Station, TX

de Silva HJ et al (2000) Suicide in Sri Lanka: points to ponder. Ceylon Med J 45(1):17–24

Eddleston M et al (2005) Epidemiology of intentional self-poisoning in rural Sri Lanka. Br J Psychiatry 187:583–584

Ministry of Health (2006) Annual Health Bulletin. Ministry of Health, Colombo

Gunnell DJ, Brooks J, Peters TJ (1996) Epidemiology and patterns of hospital use after parasuicide in the south west of England. J Epidemiol Community Health 50(1):24–29

Gunnell D, Ho D, Murray V (2004) Medical management of deliberate drug overdose: a neglected area for suicide prevention? Emerg Med J 21(1):35–38

Spicer RS, MIller TR (2000) Sucide acts in 8 states: incidence and case fatality rates by demographics and methods. Am J Public Health 90(12):1885–1891

Thomas M et al (2000) Profile of hospital admissions following acute poisoning-experiences from a major teaching hospital in south India. Adverse Drug React Toxicol Rev 19(4):313–317

Singh S et al (1997) Changing pattern of acute poisoning in adults: experience of a large north-west Indian hospital 1970–1989. J Assoc Physicians India 45:194–197

Acknowledgments

We thank SACTRC doctors, directors, medical and nursing staff of the study hospitals for their immense support. The work was funded by a Wellcome Trust/NHMRC International Collaborative Research Grant GR071669MA to SACTRC and a Career Development Fellowship to ME (GR063560MA). DG is a senior investigator at National Institute for Health Research (NIHR).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, F., Perera, A., Wijayaweera, K. et al. The prevalence of previous self-harm amongst self-poisoning patients in Sri Lanka. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46, 517–520 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0217-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0217-z