Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Diabetes has been identified as a risk factor for poor prognosis of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). The aim of this study is to identify high-risk phenotypes of diabetes associated with COVID-19 severity and death.

Methods

This is the first edition of a living systematic review and meta-analysis on observational studies investigating phenotypes in individuals with diabetes and COVID-19-related death and severity. Four different databases were searched up to 10 October 2020. We used a random effects meta-analysis to calculate summary relative risks (SRR) with 95% CI. The certainty of evidence was evaluated by the GRADE tool.

Results

A total of 22 articles, including 17,687 individuals, met our inclusion criteria. For COVID-19-related death among individuals with diabetes and COVID-19, there was high to moderate certainty of evidence for associations (SRR [95% CI]) between male sex (1.28 [1.02, 1.61], n = 10 studies), older age (>65 years: 3.49 [1.82, 6.69], n = 6 studies), pre-existing comorbidities (cardiovascular disease: 1.56 [1.09, 2.24], n = 8 studies; chronic kidney disease: 1.93 [1.28, 2.90], n = 6 studies; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 1.40 [1.21, 1.62], n = 5 studies), diabetes treatment (insulin use: 1.75 [1.01, 3.03], n = 5 studies; metformin use: 0.50 [0.28, 0.90], n = 4 studies) and blood glucose at admission (≥11 mmol/l: 8.60 [2.25, 32.83], n = 2 studies). Similar, but generally weaker and less precise associations were observed between risk phenotypes of diabetes and severity of COVID-19.

Conclusions/interpretation

Individuals with a more severe course of diabetes have a poorer prognosis of COVID-19 compared with individuals with a milder course of disease. To further strengthen the evidence, more studies on this topic that account for potential confounders are warranted.

Registration

PROSPERO registration ID CRD42020193692.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The WHO declared coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), a disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), a global pandemic [1]. As of the 5 November 2020, more than 48.1 million cases of SARS-CoV-2 infections and more than 1.2 million deaths have been reported worldwide [2]. Among other concomitant medical conditions (e.g., underlying CVD, respiratory diseases, hypertension and obesity), diabetes has been identified as a risk factor for poor prognosis among individuals with COVID-19 [3,4,5,6]. Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses on diabetes and COVID-19 prognosis have observed an approximately two- to threefold increased risk of mortality due to COVID-19 for people with diabetes compared with people without diabetes [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

However, diabetes is a complex and heterogeneous disease and recent studies have found that there are differences in associations of specific phenotypes of diabetes with comorbidities and complications [15]. Regarding COVID-19, phenotypes related to more severe forms of diabetes, such as uncontrolled blood glucose, the presence of diabetes-related complications, a higher BMI, elevated biomarkers for liver damage and inflammation, are linked to early death, endotracheal intubations or admission to intensive care units (ICUs) [16,17,18]. However, some of the findings are still conflicting, imprecisely estimated or affected by risk of bias, such as confounding. Thus, findings from single studies are difficult to translate to clinical practice. To provide the best available evidence for the identification of risk phenotypes of diabetes in association with COVID-19 severity and death, a systematic review and meta-analysis is needed that summarises the findings, reveals more robust estimates, considers risk of bias and evaluates the certainty of evidence. Therefore, we are conducting a living systematic review and meta-analysis on the associations between phenotypes of diabetes and confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection with relation to COVID-19 death and severity.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

This is the first edition of a living systematic review and meta-analysis, which was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [19]. We plan to update the living review frequently, as long as relevant evidence on this topic becomes available. We searched PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), Web of Science (www.webofknowledge.com), Epistemonikos (www.epistemonikos.org) and the COVID-19 Research Database (WHO) (https://search.bvsalud.org/global-literature-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov). A protocol was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020193692). The literature search was conducted from inception up to 14 August 2020 by using predefined search terms (see electronic supplementary material (ESM) Table 1). To identify studies that were published after the last update, we continuously searched PubMed using the e-mail alert service, which was based on our search terms described above. The last update was on 10 October 2020. We did not apply any restrictions or filters. The screening of the studies was performed by two independent researchers (AL, MN) and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion with two other researchers (CH, SS). Titles and abstracts were scanned according to the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria (see below) and potentially relevant full texts were assessed for eligibility. Reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews on this topic were screened for further relevant studies.

We included studies of any design that reported risk estimates (HR, RR or OR with 95% CI) for associations between phenotypes (general characteristics of individuals, diabetes-specific characteristics, presence of diabetes-related complications or underlying comorbidities, and laboratory parameters) and death and severity of COVID-19 in individuals with diabetes and WHO-defined confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection [20]. Severity of COVID-19 was defined as a composite endpoint, including death, endotracheal intubation for mechanical ventilation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, septic shock, ICU admission, multiple organ dysfunction or failure, or hospital admission. Studies without primary clinical data (including modelling studies), editorials, letters, commentaries, reviews, articles not in English and guidelines were excluded. If studies on the same cohort/data were identified, we selected the study with the largest number of cases. Studies with mixed populations (including individuals without diabetes or without COVID-19) were excluded [21,22,23]. We successfully contacted study authors and received missing data or corrections for implausible data [16, 17, 24,25,26,27] and, thus, no study had to be excluded due to missing data. As the authors of one report did not reply to our request [28], we assumed that in statistical analyses of continuous measures, the variable was investigated as per 1 unit increase.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

One investigator extracted relevant data using a pre-piloted form and another investigator double-checked it for accuracy (AL, MN). Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by discussion with a third researcher (SS). The extracted data of interest are listed in ESM Table 2.

Three researchers (AL, MN, SS) independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies in pairs of two by applying the validated Cochrane tool, Quality In Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) [29]. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion. The tool includes the following six domains: study participation, study attrition, prognostic factor measurements, outcome measurements, study confounding and statistical analysis/reporting (see ESM Methods and ESM Table 3 for more details).

Data analysis

For similar exposures (with similar reference groups [e.g., men vs women; obese vs normal weight; use of insulin: yes vs no; pre-existing comorbidities: yes vs no]), meta-analyses were conducted separately for the two outcomes: death and severity. We calculated summary RRs (SRR) and 95% CIs using DerSimonian and Laird random effects models and I2 statistic to assess statistical heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of the funnel plots and applying Egger’s test if more than ten studies were identified for one association [30]. To explore the influence of potential confounding, we conducted stratified analysis by adjustment for important confounders (low/moderate risk vs high risk of bias in the confounding domain of the QUIPS tool). We defined low risk of bias as inclusion of a minimal adjustment set in the statistical analysis (including age, sex, BMI, at least one comorbid condition), moderate if one of the aforementioned confounders was missing, and high if more than one of the aforementioned confounders was missing and/or univariate analyses were conducted. Since it has been shown that the 95% CIs derived from the DerSimonian and Laird method can provide false-positive findings when summarising few studies with small sample sizes, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by calculating the 95% CIs derived from the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method, which has been shown to result in more adequate error rates than the DerSimonian and Laird method [31]. All statistical analyses were conducted with Stata software version 15.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Certainty of evidence

Certainty of evidence of pooled associations was evaluated by two authors independently (MN, SS) using the GRADE tool [32]. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. The tool covers the following aspects: study design, risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, publication bias, the magnitude of effects, dose–response relations and the impact of residual confounding. The certainty of evidence could be rated as high, moderate, low or very low. The certainty of evidence is described as the ‘extent of the confidence that a risk estimate of an association is correct or is adequate with the aim to support a particular decision or recommendation’ [33]. A high certainty of evidence means that it is very unlikely that the inclusion of future studies will change the effect estimate, whereas a very low certainty of evidence means that it is very likely that the inclusion of future studies will change the results.

Results

Literature search and characteristics of included studies

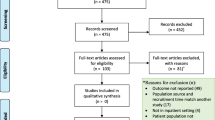

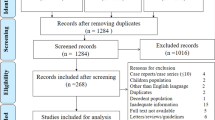

In total, 4150 records were identified from the databases. After exclusion of duplicates, the titles and abstracts from 2546 articles were screened and, out of these, 213 articles were read in full length. Five relevant articles were identified from the PubMed e-mail alert service. In total, 22 articles [16,17,18, 24,25,26,27,28, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] were included (Fig. 1). The number of people (with diabetes and COVID-19) ranged from 29 (smallest study) to 9460 (largest study). In total, our systematic review included 17,687 individuals. The reasons for exclusion of studies are provided in ESM Table 4. Most of the studies (n = 14) were conducted in Asia (China, n = 8; South Korea, n = 3; Singapore, n = 1; Iran, n = 1; Israel n = 1), whilst five studies were conducted in North America (USA, n = 4; Mexico, n = 1) and three studies in Europe (France, n = 1; Italy, n = 1; Spain, n = 1). The majority of the studies were conducted in the hospital setting and used data from hospital-based records, with a few exceptions: one study included data from a national registry [17] and two used data from health insurance records [40, 41]. Type of diabetes was not specified in n = 13 studies, n = 5 studies only included individuals with type 2 diabetes and n = 4 studies focused on both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The characteristics of the studies are shown in Table 1 and more detailed information about the setting, the identified exposures and considered confounders in each study is shown in ESM Table 5. Risk of bias was low in n = 6 studies, moderate in n = 8 studies and high in n = 8 studies (ESM Fig. 1). The main reason for high risk of bias was insufficient adjustment for confounding factors and/or inappropriate statistical analysis and reporting of the findings (ESM Fig. 2).

General risk factors and COVID-19-related death and COVID-19 severity in individuals with diabetes and COVID-19

There is high certainty of evidence that male sex compared with female sex was associated with increased risk of COVID-19-related death (SRR 1.28 [95% CI 1.02, 1.61]; n = 10 studies) and COVID-19 severity (SRR 1.36 [95% CI 1.13, 1.64]; n = 11 studies) in individuals with diabetes and COVID-19. In addition, older age (>65 years) was associated with higher risk of COVID-19-related death (SRR 3.49 [95% CI 1.82, 6.69]; n = 6 studies; moderate certainty of evidence) and with COVID-19 severity (SRR 1.67 [95% CI 1.00; 2.76]; n = 6 studies; low certainty of evidence). With each 5 year increase in age, the relative risk for COVID-19-related death increased by 43% (95% CI 12%, 83%; n = 5 studies) and for severity by 25% (95% CI 11%, 40%; n = 7 studies), both with moderate certainty of evidence. There were no clear associations between smoking, being overweight and being obese with risk of COVID-19-related death or COVID-19 severity (certainty of evidence ranged from very low to moderate) (Figs 2, 3, ESM Table 6 and ESM Table 7).

Prognostic factors and COVID-19-associated death in individuals with diabetes and COVID-19. aPoorly controlled blood glucose was defined as when the lowest fasting blood glucose was ≥3.9 mmol/l and the highest 2 h plasma glucose level exceeded 10.0 mmol/l during the observation window. bRenin inhibitors included ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) and non-specified renin–angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors. DPP4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase

Prognostic factors and severity of COVID-19 in individuals with diabetes and COVID-19. Severity is defined as a composite endpoint including death, tracheal intubation for mechanical ventilation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, septic shock, intensive care unit admission, multiple organ dysfunction or failure, or hospital admission. aPoorly controlled blood glucose defined as when the lowest fasting blood glucose was ≥3.9 mmol/l and the highest 2 h plasma glucose level exceeded 10.0 mmol/l during the observation window. bRenin inhibitors included ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) and non-specified renin–angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors. DPP4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase

Diabetes-specific risk factors and COVID-19-related death and COVID-19 severity in individuals with diabetes and COVID-19

Only a few studies investigated diabetes-specific factors related to COVID-19; thus the estimates were mostly imprecisely estimated and certainty of evidence was mainly low or very low. No association was observed between HbA1c and risk of COVID-19-related death or severity of COVID-19. Higher blood glucose at admission was associated with increased risk of COVID-19-related death and severity. The strongest associations were observed for blood glucose levels >11 mmol/l at admission and death (SRR 8.60 [95% CI 2.25, 32.83]; n = 2 studies; moderate certainty of evidence). With each 1 mmol/l increase in blood glucose at admission, the relative risk for COVID-19-related death and severity of COVID-19 increased by 10% (death: 10% [95% CI 5%, 16%], n = 2 studies; severity: 10% [95% CI 4%, 16%], n = 3 studies; low certainty of evidence for both). Participants with chronic insulin use compared with non-users of insulin had a higher relative risk of dying (SRR 1.75 [95% CI 1.01, 3.03]; n = 5 studies; high certainty of evidence), while participants using metformin compared with non-users of metformin were at lower relative risk of dying (SRR 0.50 [95% CI 0.28, 0.90]; n = 4 studies; moderate certainty of evidence) (Figs 2, 3, ESM Table 6 and ESM Table 7).

Comorbidities, complications and medication use and COVID-19-related death and COVID-19 severity in individuals with diabetes and COVID-19

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was associated with increased risk of COVID-19-related death (SRR 1.40 [1.21, 1.62]; n = 5 studies) and COVID-19 severity (SRR 1.36 [95% CI 1.11, 1.66]; n = 6 studies), both graded as high certainty of evidence. Moderate certainty of evidence was observed for associations between total CVD (SRR 1.56 [95% CI 1.09, 2.24]; n = 8 studies) and chronic kidney disease (CKD; SRR 1.93 [95% CI 1.28, 2.90]; n = 6 studies) with COVID-19-related death, and low certainty of evidence was observed for associations between cerebrovascular diseases and death (SRR 2.11 [95% CI 1.36, 3.26]; n = 2 studies). In general, the associations for these comorbidities and complications were weaker for COVID-19 severity and imprecisely estimated, with the exception of COPD.

No clear associations could be observed for hypertension, cancer (type not specified), any comorbidity, liver disease, dementia, statin use and renin inhibitor use (including ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers [ARBs] and non-specified renin–angiotensin system [RAS] inhibitors) before admission with COVID-19 severity and/or COVID-19-related death (certainty of evidence very low to moderate). (Figs 2, 3, ESM Table 6 and ESM Table 7).

Laboratory parameters on admission and COVID-19-related death and COVID-19 severity in individuals with diabetes and COVID-19

There was an association of white blood cell and neutrophil counts with elevated relative risk of COVID-19-related death and COVID-19 severity (low to very low certainty of evidence), and for creatinine with COVID-19 severity (moderate certainty of evidence). Lymphocyte count (per 1 × 109/l) was inversely associated with both outcomes (death: SRR 0.28 [95% CI 0.09, 0.87], n = 4 studies, low certainty of evidence; severity: SRR 0.33 [95% CI 0.14, 0.79], n = 4 studies, moderate certainty of evidence). For C-reactive protein (CRP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and albumin, associations were imprecisely estimated and certainty of evidence was very low (Figs 2, 3, ESM Table 6 and ESM Table 7).

Subgroup analysis, heterogeneity, publication bias and sensitivity analysis

For each association, meta-analyses were stratified by low/moderate vs high risk of bias due to confounding (ESM Fig. 3–41). Apparently, but imprecisely estimated, stronger associations were observed for older age (>65 years; ESM Fig. 4) and CKD (ESM Fig. 25) with COVID-19-related death in studies with high risk vs low/moderate risk of bias due to confounding (SRR [95%] for between studies for age > 65 years: 3.63 [0.86, 15.29], pbetween studies = 0.07; SRR [95%] for between studies for CKD: 2.53 [0.93, 6.88], pbetween studies = 0.06). In general, heterogeneity was higher for severity than for COVID-19-related death (Figs 2, 3), which could be explained by the inclusion of different criteria for severity and for outcomes as a composite outcome. In addition, we identified high heterogeneity especially for the laboratory findings, which is likely due to different analytical methods and reference ranges.

Publication bias was only examined for male sex (≥10 studies), and publication bias was not observed for COVID-19-related death or COVID-19 severity (ESM Fig. 42).

In a sensitivity analysis, we calculated the 95% CIs by applying the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method. In general, the findings were comparable. The discrepancies were mainly observed for meta-analyses based on few numbers of primary studies (n ≤ 5; ESM Table 8 and ESM Table 9).

Discussion

In our living systematic review and meta-analysis, we summarised the current knowledge on associations between phenotypes of individuals with diabetes and confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection regarding COVID-19-related death and COVID-19 severity and evaluated their certainty of evidence. Moderate to high certainty of evidence for higher risk of COVID-19-related death was observed for male sex, older age, CVD, CKD, COPD, high plasma blood glucose at admission and chronic insulin use. Metformin use was inversely associated with death. For COVID-19 severity, similar associations were observed in general, but estimates were lower and less precise.

Older age, male sex, obesity, hypertension, chronic pulmonary diseases, CVD, active cancer [3,4,5,6, 21], laboratory parameters (e.g. low lymphocyte count, and elevations in CRP, ALT and AST) [48] have been linked to a poor prognosis of COVID-19 in the general population infected with SARS-CoV-2. These risk factors among the general population are in line with the risk factors we identified in the diabetes populations, with some exceptions. Interestingly, we did not observe a positive association for obesity or hypertension with COVID-19 severity or death in people with diabetes and COVID-19. In addition, higher white blood cell (leucocyte) and neutrophil counts and lower lymphocyte counts also increased the relative risk for COVID-19-related death and COVID-19 severity in our meta-analyses. Nevertheless, we observed no clear associations for CRP (the most frequently measured biomarker of inflammation) or for liver enzymes (ALT, AST). However, only two to four primary studies in our meta-analyses included these biomarkers, and the certainty of evidence was low or very low, meaning that it is likely or very likely that further studies might change the results. Interestingly, findings from a large representative study in England indicated that higher HbA1c was associated with poor prognosis of COVID-19 in individuals with diabetes: the RR (95% CI) for HbA1c < 7.5% (<58.5 mmol/mol) and death was 1.31 (1.24, 1.37), and for HbA1c ≥ 7.5% (≥58.5 mmol/mol), it was 1.95 (1.83, 2.08) compared with individuals without diabetes [20]. In another population-based study of participants with diabetes (but not all with SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis), associations between HbA1c levels and death related to COVID-19 was less clear [23], which is comparable with our findings. Only at HbA1c values of ≥10% (≥85.8 mmol/mol) was a clear association observed (RR 2.23 [95% CI 1.50, 3.30]) compared with individuals with HbA1c values between 6.5% (47.5 mmol/mol) and 7% (53 mmol/mol).

Furthermore, high blood glucose at admission has been shown to be a marker for poor prognosis of COVID-19, even in individuals without pre-existing diabetes [49]. One study reported that individuals with well-controlled diabetes had a better prognosis of COVID-19 compared with individuals with poorly controlled diabetes [47]. In our meta-analysis, higher blood glucose at admission was also associated with worse prognosis of COVID-19. The certainty of evidence was very low to moderate because of the limited number of original studies.

Regarding glucose-lowering medication, chronic insulin use was associated with higher risk of COVID-19-related death, while metformin use was associated with lower risk. We speculate that it is not the treatment, per se, that is associated with prognosis of COVID-19, but rather that it represents an indicator of severity of diabetes. Unfortunately, our meta-analyses did not allow for stratification by diabetes severity or duration. We could also not stratify our meta-analyses by diabetes type.

Nevertheless, we observed a higher relative risk for COVID-19-related death when comparing type 2 with type 1 diabetes, but the findings were not statistically significant and only based on two studies and, thus, certainty of evidence was very low. On the contrary, a large population-based study from England indicated that, when compared with individuals without diabetes, individuals with type 1 diabetes had a worse prognosis than individuals with type 2 diabetes [22]. Holman et al. showed in their study (which included participants with diabetes but not all with SARS-CoV-2 infection) that age, sex, hypertension, obesity and comorbidities were associated with COVID-19-related death for both type 1 and type 2 diabetes [23]. Moreover, in these population-based studies, socioeconomic deprivation was associated with COVID-19-related death [21, 23]; we could not investigate associations with socioeconomic deprivation in our meta-analysis because these data were not available from the primary studies included.

After our last update, eligible studies providing important data have been published on this topic, such as the report from McGurnaghan et al., which covered the whole Scottish population, including individuals with diabetes [50]. In general, the data support our findings but provide new insights on further risk factors not included in our study. For example, a higher level of deprivation, any admission due to diabetic ketoacidosis or hypoglycaemia in the previous 5 years, pre-existing immune diseases, use of immunosuppressants and evidence for retinopathy were all associated with severity of COVID-19.

Taken together, the risk group we identified for the population with diabetes and COVID-19, i.e. older individuals with comorbid conditions and using insulin, might simply reflect severity of diabetes or poor health conditions per se. Nevertheless, considering these phenotypes can be helpful for identifying people with diabetes and COVID-19 at high risk for poor outcomes and, therefore, those most likely to require early intensified treatment.

The strengths of our report include the comprehensive literature search that used four different databases, the assessment of risk of bias of the primary studies using a validated tool, the consideration of risk of bias due to confounding in our analysis and the assessment of the certainty of evidence by following the GRADE approach. In addition, our living review will be updated continuously and provide information regarding the best evidence on prognosis of COVID-19 among individuals with diabetes.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, there was a low number of primary studies for some of the associations assessed, including diabetes-specific factors (e.g. diabetes duration, HbA1c, use of specific glucose-lowering medications), certain comorbidities (e.g. cancer, liver disease, and dementia) and laboratory parameters at admission (e.g. CRP, differential blood cell count, liver enzymes). For these associations, the certainty of evidence was mainly graded as low or very low, reflecting that future research might change the findings. Second, the risk of bias was high for eight studies (36% of the studies included), mainly due to insufficient adjustment of important confounders. However, we stratified our meta-analyses by risk of bias due to confounding and the overall findings were robust, with two exceptions; older age and CKD were more strongly associated with COVID-19-related death in studies with high risk of bias compared with studies with low or moderate risk of bias due to confounding. Third, it was not possible to conduct stratified analyses by study design, data collection and diabetes type. Fourth, the primary studies did not account for possible specific treatment of COVID-19. Fifth, a general question remains as to whether deceased participants died with or due to COVID-19. Finally, these findings cannot be generalised to all individuals with diabetes infected with SARS-CoV-2 because only individuals with the more severe form of COVID-19 are included in the primary studies and the majority of the studies were conducted in the hospital setting.

In conclusion, our living systemic review and meta-analysis provides the best current evidence on associations between phenotypes of individuals with diabetes and confirmed SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19-related death and severity of COVID-19. Male sex, older age and pre-existing comorbidities (CVD, CKD and COPD), as well as the use of insulin, most of which are potential indicators for a more progressive course of diabetes, were associated with increased risk of COVID-19-related death and severity in individuals with diabetes and SARS-CoV-2, whereas metformin use had associations in the opposite direction. To strengthen the evidence, more primary studies investigating diabetes-specific risk factors, e.g. type and duration of diabetes or additional comorbidities (such as liver disease and neuropathy), and accounting for important confounders, are needed. We will continuously update this report to strengthen the evidence of already examined associations and to investigate further outcomes, such as long-term complications due to COVID-19 for individuals with diabetes.

Data availability

Data were extracted from published research papers, all of which are available and accessible. All datasets generated during the current study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors. The study protocol has been published (PROSPERO ID: CRD42020193692; www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/) and is unrestrictedly available.

Change history

19 June 2023

Editor's note: In rapidly evolving research areas information can change quickly. A living systematic review is one that is regularly updated to incorporate relevant new evidence as it becomes available. This living systematic review has now been updated and the article is available at:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-023-05928-1

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease-2019

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- QUIPS:

-

Quality In Prognosis Studies

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2

- SRR:

-

Summary relative risks

References

World Health Organization (2020) WHO announces COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic. Available from: www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic. Accessed: October 2020

John Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center (2020) COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed: October 2020

Li X, Guan B, Su T et al (2020) Impact of cardiovascular disease and cardiac injury on in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart 106(15):1142–1147. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317062

Foldi M, Farkas N, Kiss S et al (2020) Obesity is a risk factor for developing critical condition in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 21(10):e13095

Sanchez-Ramirez DC, Mackey D (2020) Underlying respiratory diseases, specifically COPD, and smoking are associated with severe COVID-19 outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Med 171:106096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106096

Nandy K, Salunke A, Pathak SK et al (2020) Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the impact of various comorbidities on serious events. Diabetes Metab Syndr 14(5):1017–1025

Mantovani A, Byrne CD, Zheng MH, Targher G (2020) Diabetes as a risk factor for greater COVID-19 severity and in-hospital death: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 30(8):1236–1248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2020.05.014

Huang I, Lim MA, Pranata R (2020) Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia - a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes Metab Syndr 14(4):395–403

Kumar A, Arora A, Sharma P et al (2020) Is diabetes mellitus associated with mortality and severity of COVID-19? A meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr 14(4):535–545

Parohan M, Yaghoubi S, Seraji A, Javanbakht MH, Sarraf P, Djalali M (2020) Risk factors for mortality in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Aging Male. https://doi.org/10.1080/13685538.2020.1774748

Li J, He X, Yuan Y et al (2021) Meta-analysis investigating the relationship between clinical features, outcomes, and severity of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pneumonia. Am J Infect Control 49(1):82–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.06.008

Guo L, Shi Z, Zhang Y et al (2020) Comorbid diabetes and the risk of disease severity or death among 8807 COVID-19 patients in China: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 166:108346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108346

Zhou Y, Yang Q, Chi J et al (2020) Comorbidities and the risk of severe or fatal outcomes associated with coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 99:47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.07.029

Shang L, Shao M, Guo Q et al (2020) Diabetes mellitus is associated with severe infection and mortality in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Med Res 51(7):700–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.07.005

Zaharia OP, Strassburger K, Strom A et al (2019) Risk of diabetes-associated diseases in subgroups of patients with recent-onset diabetes: a 5-year follow-up study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 7(9):684–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30187-1

Cariou B, Hadjadj S, Wargny M et al (2020) Phenotypic characteristics and prognosis of inpatients with COVID-19 and diabetes: the CORONADO study. Diabetologia 63(8):1500–1515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05180-x

Bello-Chavolla OY, Bahena-Lopez JP, Antonio-Villa NE et al (2020) Predicting mortality due to SARS-CoV-2: a mechanistic score relating obesity and diabetes to COVID-19 outcomes in Mexico. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 105(8):dgaa346

Liu Z, Bai X, Han X et al (2020) The association of diabetes and the prognosis of COVID-19 patients: a retrospective study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 169:108386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108386

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

World Health Organization (2020) WHO COVID-19: case definitions: updated in public health surveillance for COVID-19. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/337834. (Accessed: March 2021)

Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K et al (2020) Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 584(7821):430–436. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4

Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P et al (2020) Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 8(10):813–822. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30272-2

Holman N, Knighton P, Kar P et al (2020) Risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in England: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 8(10):823–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30271-0

Rastad H, Karim H, Ejtahed HS et al (2020) Risk and predictors of in-hospital mortality from COVID-19 in patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Diabetol Metab Syndr 12:57

Agarwal S, Schechter C, Southern W, Crandall JP, Tomer Y (2020) Preadmission diabetes-specific risk factors for mortality in hospitalized patients with diabetes and coronavirus disease 2019. Diabetes Care 43(10):2339–2344. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-1543

Li Y, Han X, Alwalid O et al (2020) Baseline characteristics and risk factors for short-term outcomes in 132 COVID-19 patients with diabetes in Wuhan China: a retrospective study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 166:108299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108299

Shi Q, Zhang X, Jiang F et al (2020) Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality of COVID-19 patients with diabetes in Wuhan, China: a two-center, retrospective study. Diabetes Care 43(7):1382–1391. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-0598

Acharya D, Lee K, Lee DS, Lee YS, Moon SS (2020) Mortality rate and predictors of mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients with diabetes. Healthcare 8(3):338. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030338

Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Cote P, Bombardier C (2013) Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med 158(4):280–286. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009

Higgins JPT, Green S (2011) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from: www.handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed October 2020

IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF (2014) The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol 14:25

Schunemann HJ, Cuello C, Akl EA et al (2019) GRADE guidelines: 18. How ROBINS-I and other tools to assess risk of bias in nonrandomized studies should be used to rate the certainty of a body of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 111:105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.01.012

Balshem H, Helfand M, Schunemann HJ et al (2011) GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 64(4):401–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015

Chen Y, Yang D, Cheng B et al (2020) Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with diabetes and COVID-19 in association with glucose-lowering medication. Diabetes Care 43(7):1399–1407. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-0660

Chung SM, Lee YY, Ha E et al (2020) The risk of diabetes on clinical outcomes in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Metab J 44(3):405–413. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2020.0105

Crouse A, Grimes T, Li P, Might M, Ovalle F, Shalev A (2021) Metformin use is associated with reduced mortality in a diverse population with Covid-19 and diabetes. Front Endocrinol 11:600439

Dalan R, Ang LW, Tan WYT et al (2020) The association of hypertension and diabetes pharmacotherapy with COVID-19 severity and immune signatures: an observational study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa098

de Abajo FJ, Rodriguez-Martin S, Lerma V et al (2020) Use of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of COVID-19 requiring admission to hospital: a case-population study. Lancet 395(10238):1705–1714. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31030-8

Luo P, Qiu L, Liu Y et al (2020) Metformin treatment was associated with decreased mortality in COVID-19 patients with diabetes in a retrospective analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 103(1):69–72. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0375

Merzon E, Green I, Shpigelman M et al (2020) Haemoglobin A1c is a predictor of COVID-19 severity in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev e3398. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3398

Rhee S, Lee J, Nam H, Kyoung D, Kim D (2021) Effects of a DPP-4 inhibitor and RAS blockade on clinical outcomes of patients with diabetes and COVID-19. Diabetes Metab J 45:251–259

Seiglie J, Platt J, Cromer SJ et al (2020) Diabetes as a risk factor for poor early outcomes in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Diabetes Care. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-1506

Shah P, Owens J, Franklin J, Jani Y, Kumar A, Doshi R (2020) Baseline use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/AT1 blocker and outcomes in hospitalized coronavirus disease 2019 African-American patients. J Hypertens 38:2537–2541

Shang J, Wang Q, Zhang H et al (2020) The relationship between diabetes mellitus and COVID-19 prognosis: a retrospective cohort study in Wuhan, China. Am J Med 134(1):E6–E14

Solerte SB, D'Addio F, Trevisan R et al (2020) Sitagliptin treatment at the time of hospitalization was associated with reduced mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes and COVID-19: a multicenter, case-control, retrospective, observational study. Diabetes Care 43(12):2999–3006. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-1521

Xu Z, Wang Z, Wang S et al (2020) The impact of type 2 diabetes and its management on the prognosis of patients with severe COVID-19. J Diabetes. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-0407.13084

Zhu L, She ZG, Cheng X et al (2020) Association of blood glucose control and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and pre-existing type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab 31(6):1068–1077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2020.04.021

Malik P, Patel U, Mehta D et al (2020) Biomarkers and outcomes of COVID-19 hospitalisations: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Evid Based Med. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111536

Wang S, Ma P, Zhang S et al (2020) Fasting blood glucose at admission is an independent predictor for 28-day mortality in patients with COVID-19 without previous diagnosis of diabetes: a multi-centre retrospective study. Diabetologia 63(10):2102–2111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05209-1

McGurnaghan SJ, Weir A, Bishop J et al (2021) Risks of and risk factors for COVID-19 disease in people with diabetes: a cohort study of the total population of Scotland. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 9(2):82–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30405-8

Authors’ relationships and activities

CH received speaker’s honoraria from Sanofi-Aventis and Lilly and research support from Sanofi-Aventis.

MR received personal fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim Pharma, Eli Lilly, Fishawack Group, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi US, Target NASH and Terra Firma, and investigator-initiated research support from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Nutricia/Danone and Sanofi-Aventis. All other authors declare that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The German Diabetes Center (DDZ) is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Science and Culture of the State North Rhine-Westphalia. This study was supported in part by a grant from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research to the German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD). The funders had no role in study design or data collection, analysis and interpretation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MR and SS designed the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AL, MN and SS performed the literature search and literature screening. CH assisted in the selection of eligible studies. AL and MN extracted data and KP assisted with extraction of data on treatment. AL, MN and SS assessed the risk of bias of the studies and MN and SS assessed the certainty of evidence of the associations. SS performed statistical analyses and OK assisted with the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to data acquisition, data interpretation, revision of manuscript drafts and have read and approved the final manuscript. SS is the guarantor of this work.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM

(PDF 9.16 mb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schlesinger, S., Neuenschwander, M., Lang, A. et al. Risk phenotypes of diabetes and association with COVID-19 severity and death: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 64, 1480–1491 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05458-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05458-8