Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

The action of incretin hormones including glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is potentiated in animal models defective in glucagon action. It has been reported that such animal models maintain normoglycaemia under streptozotocin (STZ)-induced beta cell damage. However, the role of GIP in regulation of glucose metabolism under a combination of glucagon deficiency and STZ-induced beta cell damage has not been fully explored.

Methods

In this study, we investigated glucose metabolism in mice deficient in proglucagon-derived peptides (PGDPs)—namely glucagon gene knockout (GcgKO) mice—administered with STZ. Single high-dose STZ (200 mg/kg, hSTZ) or moderate-dose STZ for five consecutive days (50 mg/kg × 5, mSTZ) was administered to GcgKO mice. The contribution of GIP to glucose metabolism in GcgKO mice was also investigated by experiments employing dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP4) inhibitor (DPP4i) or Gcg–Gipr double knockout (DKO) mice.

Results

GcgKO mice developed severe diabetes by hSTZ administration despite the absence of glucagon. Administration of mSTZ decreased pancreatic insulin content to 18.8 ± 3.4 (%) in GcgKO mice, but ad libitum-fed blood glucose levels did not significantly increase. Glucose-induced insulin secretion was marginally impaired in mSTZ-treated GcgKO mice but was abolished in mSTZ-treated DKO mice. Although GcgKO mice lack GLP-1, treatment with DPP4i potentiated glucose-induced insulin secretion and ameliorated glucose intolerance in mSTZ-treated GcgKO mice, but did not increase beta cell area or significantly reduce apoptotic cells in islets.

Conclusions/interpretation

These results indicate that GIP has the potential to ameliorate glucose intolerance even under STZ-induced beta cell damage by increasing insulin secretion rather than by promoting beta cell survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Glucagon is secreted from pancreatic alpha cells and contributes to promoting hepatic glucose production [1]. Diabetic patients show a paradoxical secretion of glucagon in response to meal test [2] and such diabetic hyperglucagonaemia is thought to be due to the relative deficiency of insulin action [3]. Thus, blockade of glucagon action is considered to be a novel target for glucose-lowering drug development [3].

Several animal models deficient in glucagon action have been reported, including prohormone convertase 2 knockout mice [4, 5], glucagon receptor knockout (Gcgr −/−) mice [6], mice treated with glucagon receptor antisense oligonucleotide [7] and mice having pancreas-specific Arx ablation [8]. All of these animal models show lower blood glucose levels, suggesting that glucagon plays a major role in hepatic glucose production and the maintenance of blood glucose levels. Moreover, several studies demonstrated that such animal models do not develop hyperglycaemia after beta cell destruction by streptozotocin (STZ) treatment [8–11], suggesting that glucagon plays an indispensable role in hyperglycaemia caused by beta cell destruction.

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) are incretins released from intestinal K- and L cells, respectively, and potentiate insulin secretion from beta cells in a glucose-dependent manner [12, 13]. GLP-1 is produced from proglucagon, which also serves as a precursor of glucagon. Several animal models deficient in glucagon action show markedly elevated plasma GLP-1 levels [5–7, 14], suggesting that GLP-1 might contribute to normoglycaemia under STZ-induced beta cell destruction via extra-pancreatic effects. We previously generated mice lacking proglucagon-derived peptides (PGDPs), including glucagon and GLP-1 (GcgKO mice) [15]. GcgKO mice display increased insulin sensitivity due to glucagon deficiency and enhanced early-phase insulin secretion in a GIP-dependent manner [16]. In the present study, we investigated glucose metabolism in GcgKO mice administered with STZ. We found that GcgKO mice developed marked hyperglycaemia under the severe insulin deficiency caused by STZ-induced beta cell destruction despite the absence of glucagon. However, GcgKO mice displayed normoglycaemia under moderate insulin deficiency caused by moderate beta cell damage. We also investigated involvement of GIP in resistance to beta cell damage in GcgKO mice.

Methods

Materials

Acetaminophen, STZ and BSA were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Anagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP4) inhibitor (DPP4i) was provided from Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co. (Nagoya, Aichi, Japan).

Animals

GcgKO mice in a C57BL/6 background were established and maintained as previously reported (Gcg tm1Yhys) [15]. GcgKO heterozygous and wild-type mice were used as controls. GcgKO and heterozygous mice express green fluorescent protein (GFP) in cells expressing the glucagon gene. GIP receptor knockout (GiprKO) mice, originally generated in the C57BL/6 background (Gipr tm1Yse) [17], were obtained from RIKEN BRC (Tsukuba, Japan) through the National Bio-Resource Project of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan. GcgKO and GiprKO mice were intercrossed to obtain Gcg–Gipr double knockout (DKO) mice [16]. All mice used in this study were male. All procedures were conducted according to protocols and regulations approved by the Nagoya University Animal Experiment Committee.

STZ treatment

To induce moderate damage to beta cells in the mice, STZ was administered i.p. at a dose of 50 mg (kg body weight [BW])−1 for five consecutive days (moderate-dose STZ [mSTZ]) [18]. To induce beta cell destruction, 200 mg STZ (kg BW)−1 was injected after 16 h-fast (high-dose STZ [hSTZ]) [19].

DPP4i treatment

Anagliptin was administered through feed water at a concentration of 0.625 mg/ml from 7 days before starting STZ treatment to the end of the experiment.

Glucose tolerance tests

OGTT and i.p. glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) (2 g/kg BW) were performed as previously described [16].

Gastric emptying

Liquid and solid phase of gastric emptying were assessed as previously described [20].

Biochemical analyses

Blood glucose levels were measured using an Antsense Blood Glucose Meter (Horiba, Kyoto, Japan). Plasma GIP and insulin were measured using Rat/Mouse GIP (total) ELISA (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) and Mouse Insulin ELISA Kit (Morinaga Institute of Biological Science, Kanagawa, Japan) as previously reported [21]. Blood samples for measurements of biologically intact GLP-1 and GIP were collected using BD P800 tubes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Plasma levels of biologically intact GLP-1 and GIP were evaluated using the following immunoassays according to manufacturers’ instructions: GLP-1, Active GLP-1 (ver. 2) Kit (Meso Scale Discovery, Rockville, MD, USA) and GIP, Mouse GIP, Active form Assay Kit (Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Gunma, Japan).

Pancreatic insulin and GIP content analysis

Pancreatic tissue was homogenised in Krebs-Ringer buffer (pH 7.4) on ice. Tissue homogenate was extracted overnight in acid-ethanol (1.5% (vol./vol.) HCl in 75% (vol./vol.) EtOH). Tissue extracts were diluted 1:100 or 1:200 for insulin measurement. Diluted extracts were measured by HTRF Insulin Kit (Cisbio Bioassays, Codolet, France). Pancreatic insulin content was corrected by tissue weight for analysis. Tissue extracts were diluted 1:3 with Krebs-Ringer buffer for GIP measurement and protein content assay. Diluted extracts were measured by Rat/Mouse GIP (total) ELISA (Merck Millipore) and BCA protein assay (Sigma-Aldrich). Pancreatic GIP content was corrected by protein content for analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue preparation and analyses have been described in detail previously [16]. Pancreas tissue was collected 1 day after the final administration of mSTZ to analyse cleaved caspase-3 and at 9 weeks of age to analyse beta cell mass. For analysis of cleaved caspase-3, sections were treated in citrate buffer-based Target Retrieval Solution (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) before primary antibody incubation. Sections were incubated overnight with primary antibodies to cleaved caspase-3 (1:300; #9661; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and/or insulin (1:150; ab7842; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). Secondary antibodies (Alexa fluor 488, 594; 1:500; A-11073, A-11037 or A-11076; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) were applied and incubated for 90 min at room temperature. Antibodies used are commercially available and widely used for immunohistochemistry. Fluorescent images were taken using BZ-9000 Fluorescence Microscope (Keyence, Osaka, Japan). The number of islets used to analyse cleaved caspase-3 was 355. The total areas of islets, insulin-positive cells (beta cells) and cleaved caspase-3 were analysed using BZ-X analyser software (Keyence).

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated by ANOVA or a Student’s t test using GraphPad Prism 6 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

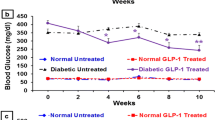

Severe hyperglycaemia is induced by hSTZ-induced beta cell ablation in GcgKO mice

To evaluate glucose metabolism under beta cell dysfunction in the GcgKO and control mice, STZ was given at a high dose (200 mg/kg, one shot; Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 1a, both GcgKO and control mice displayed severe hyperglycaemia at 4, 7 and 9 days after hSTZ administration. In accord with the blood glucose levels, plasma insulin levels were significantly decreased to <40 pmol/l in both groups (Fig. 1b). Pancreatic insulin content was analysed 9 days after hSTZ administration, and showed nearly 90% of the beta cells to be ablated in both GcgKO and control mice (Fig. 1c). These findings demonstrate that severe destruction of beta cells causes hyperglycaemia even in GcgKO mice, which lack PGDPs including glucagon, indicating that glucagon action is not requisite for persistent hyperglycaemia.

(a) Blood glucose levels, (b) plasma insulin levels and (c) pancreatic insulin content in control and GcgKO mice after hSTZ treatment (200 mg/kg). STZ was i.p. injected at a dose of 200 mg/kg BW after overnight (16 h) fast. (a) Blood glucose levels under ad libitum-fed states were measured in both GcgKO and control mice before (baseline) and at 4, 7 and 9 days after hSTZ administration. (b) Plasma insulin levels under ad libitum-fed states were measured before and 9 days after hSTZ injection. (c) Pancreatic insulin content was analysed at 9 days after hSTZ injection. **p < 0.01, saline-treated vs hSTZ-treated. White bars, saline-control; light grey bars, hSTZ-control; black bars, saline-GcgKO; dark grey bars, hSTZ-GcgKO. n = 6–9 per group

Normoglycaemia is maintained in GcgKO mice after mSTZ treatment

We next analysed glucose metabolism in mSTZ (50 mg/kg once daily for 5 days)-treated control and GcgKO mice (Fig. 2). Beta cell damage in mice treated with mSTZ was milder than that in mice treated with hSTZ by analysis of the fluorescent images of cleaved caspase-3 (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] Fig. 1). In contrast to hSTZ administration, mSTZ treatment revealed differential effects on blood glucose levels in control and GcgKO mice. As shown in Fig. 2a, blood glucose levels in mSTZ-treated GcgKO (mSTZ-GcgKO) mice were not significantly elevated compared with those in saline (154 mmol/l NaCl)-treated GcgKO (saline-GcgKO) mice, whereas those in mSTZ-treated control (mSTZ-control) mice were significantly elevated at 2 weeks and thereafter. After mSTZ administration, plasma insulin levels in control mice were significantly decreased, but they were not changed in GcgKO mice (Fig. 2b). Plasma GIP levels were significantly higher in GcgKO than in control mice. To determine whether absence of GLP-1 and increased GIP modify motility of the gastrointestinal tract in GcgKO mice, the gastric emptying rate was evaluated to assess solid phase gastric emptying. Acetaminophen absorption test also was performed to assess liquid phase gastric emptying. There was no significant difference between control and GcgKO mice in either liquid (152.02 ± 6.79 μmol/l in control; 161.66 ± 13.94 μmol/l in GcgKO; p = 0.557) or solid phase (39.3 ± 11.3% in control; 28.5 ± 12.2% in GcgKO; p = 0.539) gastric emptying rate (ESM Fig. 2).

(a) Blood glucose levels, (b) plasma insulin levels and (c) plasma GIP levels in control and GcgKO mice after mSTZ treatment in ad libitum-fed states. STZ or saline was i.p. injected once daily at a dose of 50 mg/kg BW for five consecutive days. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; NS, not significant. Significance of blood glucose levels is expressed vs saline-treated mice (a). Plasma insulin levels were evaluated at 5 weeks (b). Significance of plasma GIP levels was tested for control vs GcgKO mice (c). White circles and solid line, saline-control; black circles and solid line, mSTZ-control; white squares and dashed line, saline-GcgKO; black squares and dashed line, mSTZ-GcgKO (a). White bars, saline-control; light grey bars, mSTZ-control; black bars, saline-GcgKO; dark grey bars, mSTZ-GcgKO (b, c). n = 6–12, saline-control; n = 12–15, mSTZ-control; n = 4–10, saline-GcgKO; n = 5–12, mSTZ-GcgKO

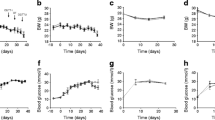

GIP contributes to glucose homeostasis in GcgKO mice

To assess the role of GIP in glucose homeostasis of mSTZ-treated GcgKO mice, we treated the DKO mice with mSTZ (mSTZ-DKO) and analysed glucose tolerance. Glucose tolerance of DKO mice without STZ treatment was comparable with that of control mice [16]. Blood glucose levels under ad libitum-fed conditions in mSTZ-DKO mice were not significantly different from those in mSTZ-GcgKO mice or non-diabetic GiprKO mice; and plasma insulin levels under ad libitum-fed conditions in mSTZ-DKO mice were not significantly different from those in mSTZ-GcgKO mice (Fig. 3a, b). However, glucose tolerance and insulin secretion during OGTT in mSTZ-DKO mice were impaired compared with those in mSTZ-GcgKO and saline-treated mice (Fig. 3c, d and data not shown), indicating a significant role of GIP in beta cell function under mSTZ-induced damage. On the other hand, no significant difference in glucose levels was observed between mSTZ-GcgKO and mSTZ-DKO mice during IPGTT (Fig. 3e). Significant increase in insulin level in response to i.p. glucose load was observed in mSTZ-GcgKO but not in mSTZ-DKO mice (Fig. 3f). The apparently differential insulin sensitivity observed between these two models might be due to presence or absence of the GIP receptor. Previous studies have shown that mice deficient in GIP action are more sensitive to insulin than control mice [22, 23].

(a) Blood glucose levels, (b) plasma insulin levels, (c, d) OGTT and (e, f) IPGTT in saline-GiprKO, mSTZ-treated GiprKO mice (mSTZ-GiprKO), mSTZ-GcgKO and mSTZ-DKO mice. OGTT and IPGTT were performed 3 and 4 weeks after mSTZ administration, respectively. Plasma insulin levels were evaluated at 5 weeks (b). White triangles and solid line, saline-GiprKO; black triangles and solid line, mSTZ-GiprKO; black squares and dashed line, mSTZ-GcgKO; black triangles and dashed line, mSTZ-DKO (a, c, e). Diagonal-striped bars, saline-GiprKO; horizontal-striped bars, mSTZ-GiprKO; dark grey bars, mSTZ-GcgKO; horizontal-striped dark grey bars, mSTZ-DKO (b, d, f). n = 8–11, saline-GiprKO; n = 6–8, mSTZ-GiprKO; n = 5, mSTZ-GcgKO; n = 5–6, mSTZ-DKO. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs mSTZ-treated GcgKO mice (a, c, e). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, †† p < 0.01; NS, not significant (d, f)

DPP4i enhances glucose-induced insulin secretion only in mSTZ-treated GcgKO mice

Because GIP and GLP-1 are rapidly inactivated by DPP4 [12], DPP4 inhibitors are widely used for clinical treatment of diabetes as an insulin secretagogue. In addition, GIP and GLP-1 are considered to play a critical role in glucose-induced insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells and anti-apoptotic action for beta cell survival mediated by DPP4 inhibition [24, 25]. To investigate whether enhancement of GIP signalling by DPP4i improves glucose tolerance and/or protects beta cells in mSTZ-GcgKO mice, DPP4i was administered as shown in Fig. 4a. This treatment improved glucose tolerance by increasing insulin secretion during OGTT in non-diabetic wild-type mice (ESM Fig. 3a, b), but did not during IPGTT (ESM Fig 3c, d). DPP4i treatment also significantly increased active GIP and GLP-1 levels during OGTT as well as under ad libitum-fed status (ESM Fig 3e–h). Treatment with DPP4i did not affect blood glucose levels under ad libitum-fed states in either control or GcgKO mice after mSTZ treatment (Fig. 4a). Pancreatic insulin content was decreased to 18.1 ± 0.2 (%) in control mice and to 18.8 ± 3.4 (%) in GcgKO mice 9 weeks after mSTZ treatment, and DPP4i did not increase pancreatic insulin content in either mSTZ-control mice or mSTZ-GcgKO mice (Fig. 4b). On IPGTT and OGTT, both mSTZ-control and mSTZ-GcgKO mice showed impaired glucose intolerance relative to the corresponding saline-treated animals (Fig. 4c, e, g, i). However, treatment with DPP4i showed differential effects on mSTZ-control and mSTZ-GcgKO mice. Treatment by DPP4i failed to improve glucose intolerance and insulin secretory response in mSTZ-control mice during IPGTT (Fig. 4c, d) and OGTT (Fig. 4g, h). On the other hand, with the same treatment in GcgKO mice, blood glucose levels were significantly reduced at 30, 60 and 120 min during IPGTT (Fig. 4e) and at 30 and 60 min during OGTT (Fig. 4i). In addition, glucose-induced insulin secretion was increased during IPGTT and OGTT by chronic DPP4 inhibition in mSTZ-GcgKO mice (Fig. 4f, j). DPP4i treatment did not improve glucose tolerance or insulin secretion in mSTZ-DKO mice (ESM Fig. 4). These results indicate that insulin secretion by GIP plays an essential role in glucose metabolism in mSTZ-GcgKO mice under treatment with DPP4i. Pancreatic GIP contents were not reduced in hSTZ- or mSTZ-control mice. On the other hand, pancreatic GIP contents were significantly reduced in hSTZ-GcgKO mice but not in mSTZ-GcgKO mice (ESM Fig. 5).

(a) Blood glucose levels, (b) pancreatic insulin content, (c–f) IPGTT and (g–j) OGTT in GcgKO and control mice treated with DPP4i. IPGTT and OGTT were performed at 6 and 7 weeks after mSTZ injection, respectively. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, vs saline-treated (a, c, e, g, i). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; NS, not significant (b, d, f, h, j). White circles and solid line, saline-control; black circles and solid line, mSTZ-control; black triangles and solid line, mSTZ-DPP4i-control; white squares and dashed line, saline-GcgKO; black squares and dashed line, mSTZ-GcgKO; black diamonds and dashed line, mSTZ-DPP4i-GcgKO (a, c, e, g, i). White bars, saline-control; light grey bars, mSTZ-control; horizontal-striped light grey bars, mSTZ-DPP4i-control; black bars, saline-GcgKO; dark grey bars, mSTZ-GcgKO; diagonal-striped dark grey bars, mSTZ-DPP4i-GcgKO (b, d, f, h, j). n = 4–7, saline-control; n = 3–7, mSTZ-control; n = 7–8, mSTZ-DPP4i-control; n = 4–9, saline-GcgKO; n = 5–9, mSTZ-GcgKO; n = 5–6, mSTZ-DPP4i-GcgKO

GIP in GcgKO mice did not enhance beta cell survival after mSTZ treatment

It was reported that endogenous GIP plays a limited role in beta cell survival in STZ-induced diabetes models [25, 26]. To investigate the role of GIP in beta cell survival in the absence of PGDPs including GLP-1, we analysed apoptosis in islets and beta cell mass in the pancreas of mSTZ-GcgKO mice. The percentage of beta cells positive for cleaved caspase-3 was increased significantly by mSTZ treatment. Treatment of mSTZ-GcgKO with DPP4i did not significantly reduce caspase-positive cells (Fig. 5a, b) and beta cell mass in DPP4i-mSTZ-GcgKO mice was comparable with that in mSTZ-GcgKO mice (Fig. 5c, d). Pancreatic insulin content was similar between GcgKO mice and DKO mice 5 weeks after mSTZ treatment (ESM Fig. 6). These results suggest that improvement of insulin secretion and glucose tolerance in mSTZ-GcgKO mice by DPP4i-treatment is mediated through mechanisms other than promotion of beta cell survival.

(a, b) Cleaved caspase-3 immunopositivity and (c, d) beta cell area of islets from GcgKO mice. (b) Representative images of cleaved caspase-3-positive islets. Red, cleaved caspase-3; green, insulin; blue, DAPI. Scale bars, 50 μm. (d) Representative images of pancreas. Red, insulin; green, GFP (glucagon); blue, DAPI. Scale bars, 300 μm. Black bars, saline-GcgKO; dark grey bars, mSTZ-GcgKO; diagonal-striped dark grey bars, mSTZ-DPP4i-GcgKO (a, c). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; NS, not significant (p = 0.07 for [a])

Discussion

Glucagon increases hepatic glucose production; insulin inhibits glucose production [27]. The relative contribution of dysregulated glucagon secretion and impairment of insulin secretion to hyperglycaemia in diabetic patients has been a matter of debate [28]. It has been shown recently that administration of STZ to Gcgr −/− mice disrupted 90% of the beta cells and abolished glucose-induced insulin secretion yet failed to cause hyperglycaemia [10]. Based on this observation, it has been proposed that hyperglucagonaemia itself plays an essential role in increasing blood glucose levels.

However, in the present study we observed that GcgKO mice lacking both glucagon and GLP-1 developed hyperglycaemia upon hSTZ-induced beta cell ablation. This difference between Gcgr −/− and GcgKO is most likely due to the presence or absence of extra-pancreatic GLP-1 action. Several studies have shown that GLP-1 exhibits extra-pancreatic action in increasing insulin sensitivity and modulating glucose metabolism [9, 20, 29]. This is supported by studies employing Gcgr −/− Glp1r −/− double knockout mice and mice with diphtheria toxin mediated-ablation of alpha and L cells (Gluc-DTR). Both models are deficient in GLP-1 action and exhibit hyperglycaemia on STZ treatment, underscoring the critical importance of GLP-1 on glycaemic control under STZ-induced beta cell ablation [30–32]. Nevertheless, there are unique characteristics among Gcgr −/− Glp1r −/−, Gluc-DTR and GcgKO mice. GcgKO mice lack all proglucagon-derived peptides throughout life, while there is a decrease in PGDPs in Gluc-DTR mice: GLP-1 synthesis in Gluc-DTR mice returns to normal levels 7 days after injection of diphtheria toxin [33]. GLP-2 is present in Gcgr −/− Glp1r −/− mice, but is reduced or absent in Gluc-DTR and GcgKO mice, respectively. Thus, the presence or absence of GLP-2 and residual glucagon in Gluc-DTR mice does not seem to affect glycaemic control under beta cell ablation.

Nevertheless, GcgKO mice, which lack GLP-1, maintain normoglycaemia after mSTZ treatment, which causes persistent hyperglycaemia in the control mice. Thus, the requirement for insulin to maintain normal blood glucose levels is lower in both GcgKO and Gcgr −/− mice [9, 15, 34, 35]. In the present study, plasma insulin levels under ad libitum-fed states were comparable between mSTZ-control and mSTZ-GcgKO mice (Fig. 2b). Insulin levels in GcgKO mice before STZ treatment were not significantly different from those after mSTZ treatment. These findings indicate that insulin plays a critical role in the maintenance of glucose levels in mSTZ-GcgKO mice. Incretins regulate insulin secretion and GIP is the major incretin in GcgKO mice, which lack GLP-1 [36].

Several reports suggest that GIP potentiates the early phase of glucose-induced insulin secretion to contribute to improved glycaemic control [16, 37–39]. GIP also has been reported to contribute to beta cell survival in vitro [40, 41], while GIP overexpression was found to enhance the increment of insulin content induced by high-fat diet feeding by decreasing beta cell apoptosis [39]. We previously reported that GIP was expressed not only in the gastrointestinal tract but also in pancreatic beta cells in GcgKO mice and that GIP hypersecretion contributes to the enhanced glucose-induced insulin secretion and improved glucose tolerance under non-diabetic states in GcgKO mice [16]. These findings led us to investigate whether GIP contributes to resistance to developing diabetes in mSTZ-GcgKO mice.

Moderate beta cell damage abolished insulin secretion in DKO but not in GcgKO mice (Fig. 3). Treatment with DPP4i potentiated glucose-induced insulin secretion and ameliorated glucose intolerance in mSTZ-GcgKO but not in mSTZ-DKO mice (Fig. 4, ESM Fig. 4). These results indicate that GIP played an important role in protecting mice deficient in PDGPs from diabetes. However, treatment with DPP4i did not significantly reduce the number of apoptotic cells in islets (Fig. 5), and blocking GIP actions did not modify pancreatic insulin content in mSTZ-treated mice (ESM Fig. 6). These results indicate that GIP does not contribute to beta cell protection in mSTZ-GcgKO mice but that it does contribute to increase insulin secretion from each of the beta cells.

It was reported recently that GIP and GLP-1 are secreted not only from enteroendocrine K- and L cells but also from pancreatic islets [16, 42–45]. In the present study, pancreatic GIP content in control mice decreased neither by hSTZ treatment nor by mSTZ treatment, most likely because GIP is expressed in pancreatic alpha cells [16, 26, 45]. On the other hand, GIP content in GcgKO pancreas was decreased by hSTZ treatment, confirming our previous results showing that GIP is expressed in beta cells in GcgKO. However, pancreatic GIP content was not changed by mSTZ treatment (ESM Fig. 5). The mechanism underlying the lack of change in pancreatic GIP content under the mSTZ-induced beta cell damage, including that of regeneration of GIP-positive cells, remains to be elucidated.

Islet-derived GLP-1 has been shown to enhance glucose-induced insulin secretion in vitro by using DPP4i in non-diabetic human and mouse islets [46]. In the present study, IPGTT and OGTT analyses suggested that both islet-derived GIP and gut-derived GIP contributes to improving glucose metabolism in mSTZ-GcgKO mice. In, addition, our results indicate that islet-derived GIP can exert an insulinotropic effect even when islet insulin contents are decreased under glucagon-deficient states. We therefore propose that combination therapy with glucagon antagonist and DPP4i might be considered as a therapeutic option to treat diabetes.

Abbreviations

- BW:

-

Body weight

- DKO:

-

Gcg–Gipr double knockout

- DPP4:

-

Dipeptidyl peptidase IV

- DPP4i:

-

DPP4 inhibitor

- GcgKO:

-

Glucagon gene knockout mice, which lack all the PGDPs including glucagon and GLP-1

- GIP:

-

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide

- GiprKO:

-

GIP receptor knockout

- GLP-1:

-

Glucagon-like peptide-1

- Gluc-DTR:

-

Mice with diphtheria toxin mediated-ablation of alpha and L cells

- hSTZ:

-

High-dose streptozotocin

- IPGTT:

-

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test

- mSTZ:

-

Moderate-dose streptozotocin

- PGDPs:

-

Proglucagon-derived peptides

- STZ:

-

Streptozotocin

References

Ramnanan CJ, Edgerton DS, Kraft G et al (2011) Physiologic action of glucagon on liver glucose metabolism. Diabetes Obes Metab 13(Suppl 1):S118–S125

Müller WA, Faloona GR, Aguilar-Parada E et al (1970) Abnormal alpha-cell function in diabetes. Response to carbohydrate and protein ingestion. N Engl J Med 283:109–115

Gromada J, Franklin I, Wollheim CB (2007) Alpha-cells of the endocrine pancreas: 35 years of research but the enigma remains. Endocr Rev 28:84–116

Furuta M, Yano H, Zhou A et al (1997) Defective prohormone processing and altered pancreatic islet morphology in mice lacking active SPC2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:6646–6651

Gagnon J, Mayne J, Chen A et al (2011) PCSK2-null mice exhibit delayed intestinal motility, reduced refeeding response and altered plasma levels of several regulatory peptides. Life Sci 88:212–217

Gelling RW, Du XQ, Dichmann DS et al (2003) Lower blood glucose, hyperglucagonemia, and pancreatic alpha cell hyperplasia in glucagon receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:1438–1443

Sloop KW, Cao JX-C, Siesky AM et al (2004) Hepatic and glucagon-like peptide-1-mediated reversal of diabetes by glucagon receptor antisense oligonucleotide inhibitors. J Clin Invest 113:1571–1581

Hancock AS, Du A, Liu J et al (2010) Glucagon deficiency reduces hepatic glucose production and improves glucose tolerance in adult mice. Mol Endocrinol 24:1605–1614

Conarello SL, Jiang G, Mu J et al (2007) Glucagon receptor knockout mice are resistant to diet-induced obesity and streptozotocin-mediated beta cell loss and hyperglycaemia. Diabetologia 50:142–150

Lee Y, Wang M-Y, Du XQ et al (2011) Glucagon receptor knockout prevents insulin-deficient type 1 diabetes in mice. Diabetes 60:391–397

Omar BA, Andersen B, Hald J et al (2014) Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) and glucagon-like peptide 1 contribute to diabetes resistance in glucagon receptor-deficient mice. Diabetes 63:101–110

Baggio LL, Drucker DJ (2007) Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology 132:2131–2157

Seino Y, Yabe D (2013) Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon-like peptide-1: incretin actions beyond the pancreas. J Diabetes Investig 4:108–130

Longuet C, Robledo AM, Dean ED et al (2013) Liver-specific disruption of the murine glucagon receptor produces α-cell hyperplasia: evidence for a circulating α-cell growth factor. Diabetes 62:1196–1205

Hayashi Y, Yamamoto M, Mizoguchi H et al (2009) Mice deficient for glucagon gene-derived peptides display normoglycemia and hyperplasia of islet alpha-cells but not of intestinal L-cells. Mol Endocrinol 23:1990–1999

Fukami A, Seino Y, Ozaki N et al (2013) Ectopic expression of GIP in pancreatic β-cells maintains enhanced insulin secretion in mice with complete absence of proglucagon-derived peptides. Diabetes 62:510–518

Miyawaki K, Yamada Y, Yano H et al (1999) Glucose intolerance caused by a defect in the entero-insular axis: a study in gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:14843–14847

Li Y, Hansotia T, Yusta B et al (2003) Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor signaling modulates beta cell apoptosis. J Biol Chem 278:471–478

Collombat P, Xu X, Ravassard P et al (2009) The ectopic expression of Pax4 in the mouse pancreas converts progenitor cells into alpha and subsequently beta cells. Cell 138:449–462

Ali S, Lamont BJ, Charron MJ et al (2011) Dual elimination of the glucagon and GLP-1 receptors in mice reveals plasticity in the incretin axis. J Clin Invest 121:1917–1929

Sakamoto E, Seino Y, Fukami A et al (2012) Ingestion of a moderate high-sucrose diet results in glucose intolerance with reduced liver glucokinase activity and impaired glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion. J Diabetes Investig 3:432–440

Nasteska D, Harada N, Suzuki K et al (2014) Chronic reduction of GIP secretion alleviates obesity and insulin resistance under high-fat diet conditions. Diabetes 63:2332–2343

Moffett RC, Vasu S, Flatt PR (2015) Functional GIP receptors play a major role in islet compensatory response to high fat feeding in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta 1850:1206–1214

Hansotia T, Baggio LL, Delmeire D et al (2004) Double incretin receptor knockout (DIRKO) mice reveal an essential role for the enteroinsular axis in transducing the glucoregulatory actions of dpp-iv inhibitors. Diabetes 53:1326–1335

Maida A, Hansotia T, Longuet C et al (2009) Differential importance of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide vs glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor signaling for beta cell survival in mice. Gastroenterology 137:2146–2157

Vasu S, Moffett RC, Thorens B et al (2014) Role of endogenous GLP-1 and GIP in beta cell compensatory responses to insulin resistance and cellular stress. PLoS One 9:e101005

Saltiel AR, Kahn CR (2001) Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature 414:799–806

Mitrakou A, Kelley D, Veneman T et al (1990) Contribution of abnormal muscle and liver glucose metabolism to postprandial hyperglycemia in NIDDM. Diabetes 39:1381–1390

Lee Y, Shin S, Shigihara T et al (2007) Glucagon-like peptide-1 gene therapy in obese diabetic mice results in long-term cure of diabetes by improving insulin sensitivity and reducing hepatic gluconeogenesis. Diabetes 56:1671–1679

Jun LS, Millican RL, Hawkins ED et al (2015) Absence of glucagon and insulin action reveals a role for the GLP-1 receptor in endogenous glucose production. Diabetes 64:819–827

Thorel F, Damond N, Chera S et al (2011) Normal glucagon signaling and β-cell function after near-total α-cell ablation in adult mice. Diabetes 60:2872–2882

Steenberg VR, Jensen SM, Pedersen J et al (2016) Acute disruption of glucagon secretion or action does not improve glucose tolerance in an insulin-deficient mouse model of diabetes. Diabetologia 59:363–370

Pedersen J, Ugleholdt RK, Jørgensen SM et al (2013) Glucose metabolism is altered after loss of L cells and α-cells but not influenced by loss of K cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 304:E60–E73

Watanabe C, Seino Y, Miyahira H et al (2012) Remodeling of hepatic metabolism and hyperaminoacidemia in mice deficient in proglucagon-derived peptides. Diabetes 61:74–84

Sørensen H, Winzell MS, Brand CL et al (2006) Glucagon receptor knockout mice display increased insulin sensitivity and impaired beta-cell function. Diabetes 55:3463–3469

Rorsman P, Braun M (2013) Regulation of insulin secretion in human pancreatic islets. Annu Rev Physiol 75:155–179

Widenmaier SB, Kim S-J, Yang GK et al (2010) A GIP receptor agonist exhibits beta-cell anti-apoptotic actions in rat models of diabetes resulting in improved beta-cell function and glycemic control. PLoS One 5:e9590

Seino S, Shibasaki T, Minami K (2011) Dynamics of insulin secretion and the clinical implications for obesity and diabetes. J Clin Invest 121:2118–2125

Kim S-J, Nian C, Karunakaran S et al (2012) GIP-overexpressing mice demonstrate reduced diet-induced obesity and steatosis, and improved glucose homeostasis. PLoS One 7:e40156

Trümper A, Trümper K, Hörsch D (2002) Mechanisms of mitogenic and anti-apoptotic signaling by glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in beta(INS-1)-cells. J Endocrinol 174:233–246

Ehses JA, Casilla VR, Doty T et al (2003) Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide promotes beta-(INS-1) cell survival via cyclic adenosine monophosphate-mediated caspase-3 inhibition and regulation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Endocrinology 144:4433–4445

Heller RS, Aponte GW (1995) Intra-islet regulation of hormone secretion by glucagon-like peptide-1-(7--36) amide. Am J Physiol 269:G852–G860

Hörsch D, Göke R, Eissele R et al (1997) Reciprocal cellular distribution of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) immunoreactivity and GLP-1 receptor mRNA in pancreatic islets of rat. Pancreas 14:290–294

Masur K, Tibaduiza EC, Chen C et al (2005) Basal receptor activation by locally produced glucagon-like peptide-1 contributes to maintaining beta-cell function. Mol Endocrinol 19:1373–1382

Fujita Y, Wideman RD, Asadi A et al (2010) Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide is expressed in pancreatic islet alpha-cells and promotes insulin secretion. Gastroenterology 138:1966–1975

Omar BA, Liehua L, Yamada Y et al (2014) Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) is expressed in mouse and human islets and its activity is decreased in human islets from individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 57:1876–1883

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co. Ltd for provision of anagliptin.

The authors address thanks to Yutaka Seino (Kansai Electric Power Medical Research Institute) for providing GiprKO mice and suggestions. The authors also thank H. Maeda (Kobe University) and M. Katagiri, M. Yamada and M. Yamamoto (Nagoya University) for technical assistance, and S. Seino (Kobe University) for helpful support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was supported by grants for young researchers from the Japan Association for Diabetes Education and Care to YS and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science to YS (25461338) and YHayashi (24659451, 15K15356 and 15H04681).

Duality of interest

YS and YHamada received a research grant from Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co., Ltd. All remaining authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with their contribution to this manuscript.

Contribution statement

AI, YS, NO, ST, YHamada, YO, HA and YHayashi participated in the research design; AI, YS, AF, RM, KK, YT, TI, HO and KI carried out the experiments; AI, YS and YHayashi wrote the manuscript; AI, YS, AF, RM, TI, HO, KI, NO, ST, YHamada, YO, HA and YHayashi contributed to discussions; AI, YS, KK, YT and YHayashi reviewed/revised the manuscript. DY and SS contributed to acquisition of data, intellectual discussions and writing of the manuscript. All authors gave approval of the final version to be published. YS is the guarantor of this work and had full access to all the data in the study, and takes responsibility for the integrity of data and the accuracy of data analysis.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Figures

(PDF 961 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Iida, A., Seino, Y., Fukami, A. et al. Endogenous GIP ameliorates impairment of insulin secretion in proglucagon-deficient mice under moderate beta cell damage induced by streptozotocin. Diabetologia 59, 1533–1541 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-016-3935-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-016-3935-2