Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Individuals carrying variants of the transcription factor 7-like 2 gene (TCF7L2) are at increased risk for type 2 diabetes. These metabolic genetic risk factors have been linked to diminished pancreatic islet-cell responsiveness to incretins, thus pharmacological interventions aimed at amplifying endogenous incretin biology may be affected. However, clinical evidence from randomised controlled trials so far is lacking. We investigated the influence of TCF7L2 risk alleles on the response to treatment with the dipeptidylpeptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor linagliptin from four 24 week, phase III, placebo-controlled trials.

Methods

Pharmacogenomic samples and clinical data were available from 961 patients with type 2 diabetes. Whole-blood DNA samples were genotyped for TCF7L2 single-nucleotide polymorphisms in conjunction with assessments of 24 week changes in HbA1c.

Results

Linagliptin lowered HbA1c meaningfully in all three genotypes of rs7903146 (non-risk variant carriers CC [n = 356]: −0.82% [−9.0 mmol/mol], p < 0.0001; heterozygous CT [n = 264]: −0.77% [−8.4 mmol/mol], p < 0.0001; homozygous risk variant carriers TT [n = 73]: −0.57% [−6.2 mmol/mol], p < 0.0006). No significant treatment differences were seen between CC and CT patients, although HbA1c response was reduced in TT compared with CC patients (~0.26% [~2.8 mmol/mol], p = 0.0182).

Conclusions/interpretation

Linagliptin significantly improved hyperglycaemia in patients with type 2 diabetes both with and without the TCF7L2 gene diabetes risk alleles. However, differences in treatment response were observed, indicating that diabetes susceptibility genes may be an important contributor to the inter-individual variability of treatment response.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Diabetes is a fast-growing global epidemic with an increasing prevalence worldwide [1]. Several genes have been associated with type 2 diabetes susceptibility or manifestation, including genes encoding receptors, transcription factors, cell cycle-associated proteins, modifiers of signal transduction, ion channels and others [2–4]. Recently, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of a gene encoding transcription factor 7-like 2 were shown to have the strongest known genetic risk factor for type 2 diabetes among all diabetes-associated gene SNPs [5, 6]. The risk of developing diabetes is twice as high in homozygous TCF7L2 risk variant (rs7903146) carriers (TT) compared with non-risk carriers (CC) [7, 8]. The initial findings have been replicated in independent studies in multiple ethnic populations and were summarised in a large global meta-analysis [5]. Pharmacogenetic studies reported a significant association between TCF7L2 risk variants and efficacy of sulfonylurea treatment, with a twofold greater likelihood of sulfonylurea treatment failure in TCF7L2 risk carriers [9]. The mechanisms by which TCF7L2 polymorphisms increase diabetes risk and affect the treatment response to insulin secretagogues were thought to be related to impaired incretin-induced insulin secretion, impaired suppression of glucagon or impaired glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion [10–13]. Depending on the underlying mechanism, the response to other insulin secretagogues, such as the novel class of dipeptidylpeptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, also may be affected.

Incretin hormones amplify the first phase of insulin secretion [14]. The advantage of incretin-based therapies, like orally active DPP-4 inhibitors, is that they have a glucose-dependent insulinotropic action with no intrinsic risk for causing hypoglycaemia. Linagliptin, a potent and selective inhibitor of DPP-4, improves glucose homeostasis in patients with diabetes by blocking the degradation of incretins and thus improving insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner [15, 16]. Linagliptin has been approved for the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes [16, 17]. Since linagliptin and the high-risk polymorphisms of TCF7L2 both affect the same process responsible for the first phase of insulin secretion, it can be hypothesised that the response to linagliptin therapy may differ in patients depending on their allele status. Therefore, we wanted to explore whether the efficacy response to linagliptin (i.e. change from baseline in HbA1c or change from baseline in 2 h postprandial plasma glucose [PPG] after 24 weeks of treatment) is dependent on the TCF7L2 genotype in a retrospective analysis of clinical data.

Methods

Data sources

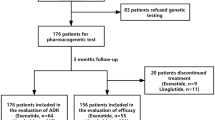

We conducted analyses of data from four phase III clinical trials—NCT00601250 [18], NCT00602472 [19], NCT00621140 [20] and NCT00641043 [21] (www.clinicaltrials.gov)—that evaluated the safety and efficacy of linagliptin, as monotherapy or in combination with other glucose-lowering therapy, in improving glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes (Table 1). Patients were on stable doses of diabetes medications or, for NCT621140, on no medications except for linagliptin or placebo. Out of a total of 2,651 patients randomised to different arms in the four trials, 987 patients gave informed consent for pharmacogenomic analyses. Both clinical and pharmacogenomic data needed for the current analyses were available for 961 patients, of which 693 were treated with linagliptin and 268 received placebo (Fig. 1). Depending on the trial, patients continued to receive other glucose-lowering medication in accordance with the objectives of that trial. Demographic and baseline characteristics of the patients included in these analyses are given in Table 2.

Clinical objectives

The primary clinical endpoint in all four studies was change in HbA1c (%) from baseline after 24 weeks of treatment, defined as difference between HbA1c (%) at 24 weeks and HbA1c (%) at baseline. A secondary objective in studies NCT00601250 [18] and NCT00621140 [20] was change from baseline in 2 h PPG.

Genotype analysis

DNA was extracted from whole-blood samples and normalised to a standard concentration of 50 ng/μl. In addition, 92 blinded DNA samples from the same study were used to validate the detected genotypes. Locus-specific DNA fragments were amplified by PCR with 50 ng genomic DNA and 5 μmol/l each of forward and reverse primers. Purified PCR products were sequenced using the Sanger method [22] in a reaction containing 2 μmol/l sequencing primer and BigDye Terminator v3.1 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The sequencing primers were selected to detect the presence of the following TCF7L2 variants in the sample: rs7903146 (C > T; intron), rs12255372 (G > T; intron), rs10885406 (A > G; intron) and rs731788 (C > G; near 3' region microRNA binding site).

Statistical analyses

Data were pooled from all randomised patients from the four trials listed (Table 1) who were treated with at least one dose of study medication, had baseline measurements of HbA1c, had at least one measurement of HbA1c while on treatment, had genetic polymorphism data available and passed the genetic mismatch quality control criteria. If the HbA1c data after 24 weeks of treatment were not available, the last observed data point was carried forward for the analysis. The homogeneity of the treatment effect on the primary endpoint change in HbA1c (%) from baseline after 24 weeks in the genotype subgroups was investigated using an ANCOVA. Baseline HbA1c was the linear covariate, while washout period for prior oral glucose-lowering therapy (yes/no), treatment-genotype group (genotype groups CC, CT and TT for patients treated with linagliptin and the placebo group), race and study were set as fixed classification effects. Pairwise comparisons between homozygous non-risk (CC) and heterozygous risk (CT) or homozygous risk (TT) variant carriers receiving linagliptin as monotherapy or in combination with other anti-hyperglycaemic agents were also performed. To evaluate how representative the subgroup of patients with available pharmacogenomic data was with respect to their response to linagliptin therapy, the results obtained from these analyses were compared with those from the corresponding ANCOVA analyses on the pooled clinical data from all patients in the four studies. Demographic variables and baseline characteristics of the genotyped subpopulation were tested for differences between treatment–genotype groups (genotype groups CC, CT and TT for patients receiving linagliptin, and the placebo group) by χ 2 test, Fisher’s exact test or ANOVA.

Additional analyses were performed to address the potential influence of study, demographic and baseline characteristics by subgroup analyses as well as by incorporating them as additional factors or covariates into the ANCOVA model. Sensitivity analysis to investigate the impact of the last observation carried forward (LOCF) imputation was performed using only observed cases. SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for all analyses.

Results

Demographic and baseline characteristics

Demographic variables and baseline characteristics were tested for differences between treatment–genotype groups (genotype groups CC, CT and TT for patients receiving linagliptin, and the placebo group). A significant difference was observed only for race (p < 0.0001) due to different frequencies of the TCF7L2 risk allele in different ethnicities (see Table 3), so race was included into the ANCOVA model. The observed slight differences for baseline weight (p = 0.0443) and BMI (p = 0.0518) had no influence on the results when including them additionally into the ANCOVA model.

Distribution of allelic and genotype frequencies

The allelic and genotype frequencies of the various TCF7L2 polymorphisms were determined for the cohort of consenting patients and the data categorised by race. The data for SNP rs7903146, which has the strongest association with type 2 diabetes, are shown in Table 3. The minor allelic frequency for the T allele was highest among white patients (34.3%) and lowest among Asian patients (18.5%), with black patients falling in the middle (20.0%). Homozygous TT occurred in 12.1% of white and 6.0% of Asian patients, but was absent in the black patients (Table 3), possibly owing to the low number of black patients participating in these studies. The observed frequencies in the white and Asian patients are concordant with publicly available allele and genotype frequencies [23, 24]. Results for the other polymorphisms and haplotypes were similar to those for rs7903146 (data not shown).

Comparison of clinical response between genotyped subgroup and all patients

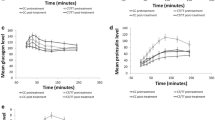

To determine whether the subgroup for which genomic analysis was performed was representative of the population of patients who participated in all four trials, the clinical response observed for the subgroup was compared with that of the whole patient population (Fig. 2). The clinical responses to treatment with linagliptin or placebo in the subgroups for which pharmacogenomic data were available were essentially identical to those of the corresponding treatment groups in the whole cohort of patients from the four clinical trials—reduction in HbA1c was similar in the two groups treated with linagliptin and HbA1c did not change from baseline in the two groups receiving placebo. These results suggest that the pharmacogenomic subgroups were representative of the entire pooled patient population.

Adjusted mean difference between HbA1c (%) at a given time and HbA1c (%) at baseline (change in HbA1c [%] from baseline) with 95% CIs for the whole cohort of patients from the four clinical trials and the subgroup for which pharmacogenomic data were available. ANCOVA model includes baseline HbA1c as linear covariate and prior oral glucose-lowering therapy (yes/no), treatment, study and treatment-by-study interaction as fixed classification effects. Placebo complete clinical data, n = 728; placebo genotyped subgroup, n = 268; linagliptin complete clinical data, n = 1,876; linagliptin genotyped subgroup, n = 693. Black triangles, placebo complete clinical data; white triangles, placebo genotyped subgroup; black circles, linagliptin complete clinical data; white circles, linagliptin genotyped subgroup. To convert values for HbA1c in DCCT % to mmol/mol, multiply by 10.929 and then subtract 23.50

Subgroup analyses

To address possible differences between the trials, we analysed each trial separately as well as in a pooled analysis again, incorporating additionally the study-by-treatment–genotype group interaction effect in the ANCOVA model. No significant heterogeneity of effects across the trials was observed. Detailed information and results of ANCOVA for each specific trial in comparison to the whole study population are given in electronic supplementary material (ESM) Table 1.

Association of genotype with clinical response

Based on TCF7L2 rs7903146 genotype, patients receiving linagliptin therapy were categorised into three groups: CC (homozygous non-risk allele carrier), CT (heterozygous) and TT (homozygous risk allele carrier). The strongest, almost identical, response to linagliptin therapy (i.e. lowering of HbA1c) was observed in patients with homozygous CC (n = 356; p < 0.0001) and heterozygous CT (n = 264; p < 0.0001) genotypes with a decrease of 0.82% (9.0 mmol/mol) and 0.77% (8.4 mmol/mol) in HbA1c, respectively, compared with baseline (Fig. 3). A less robust, but still statistically (p = 0.0006) and clinically significant, decrease of 0.57% (6.2 mmol/mol) in HbA1c in response to linagliptin therapy after 24 weeks was observed in patients who were homozygous TT (n = 73). The difference in response to linagliptin therapy between homozygous TT patients and homozygous CC patients was statistically significant (p = 0.0182).

TCF7L2 rs7903146 genotype-associated adjusted mean difference between HbA1c (%) at a given time and HbA1c (%) at baseline (change in HbA1c [%] from baseline) with 95% CIs. Linagliptin CC, n = 356; linagliptin CT, n = 264; linagliptin TT, n = 73; placebo, n = 268. ****p < 0.0001 vs placebo at 24 weeks; † p < 0.05, linagliptin-treated homozygous CC vs homozygous TT patients at 24 weeks. Black circles, linagliptin CC; black squares, linagliptin CT; white circles, linagliptin TT; black triangles, placebo. To convert values for HbA1c in DCCT % to mmol/mol, multiply by 10.929 and then subtract 23.50

The comparison of the number of patients in LOCF analyses vs the number of patients with observed 24 week data indicate that we have >80% observed cases in the linagliptin-treated group and >70% in the placebo group. The results, based only on observed cases, showed a significant difference of ~0.23% (p = 0.0392) between linagliptin-treated homozygous TT and non-risk-carrier CC patients and this is in concordance with the results obtained in the analyses for the LOCF set.

Association of genotype with PPG levels

Patients receiving placebo showed an increase from baseline in 2 h PPG levels with a mean rise of 2.13 mmol/l (ESM Fig. 1), which is likely related to the washout of previous glucose-lowering agents in the two clinical studies NCT00601250 [18] and NCT00621140 [20]. This was in accordance with an increase in HbA1c levels in the placebo group in those two studies. Similar to the observed HbA1c levels after treatment, all patients treated with linagliptin showed a decrease from baseline in 2 h PPG levels after 24 weeks. Patients homozygous for the wild-type allele (CC) showed the greatest decrease from baseline in 2 h PPG levels, with a mean decrease of 2.78 mmol/l. Although there was greater variability in patients heterozygous for the risk allele (CT), the reduction from baseline in 2 h PPG levels was similar to that observed in the homozygous CC patients, with a mean decrease of 2.55 mmol/l. Patients homozygous for the risk allele (TT) showed the smallest decrease from baseline in 2 h PPG levels (1.65 mmol/l), although it should be noted that only a few patients’ data (n = 6) was available for this group.

Discussion

The present studies have been undertaken to assess the impact of TCF7L2 genotypes on the response to incretin-based therapy, for the first time in a longitudinal setting. This is important because genetic polymorphism has been suggested to contribute to the susceptibility of individuals to environmental stimuli, resulting in increased prevalence of diabetes. Of the many genes investigated, TCF7L2, a β-catenin bipartite transcription factor, integral to the upregulation of incretin secretion from intestinal endocrine L cells and the proliferation of pancreatic beta cells [25–27], has the strongest known association with diabetes [5, 6]. The high-risk genotypes of TCF7L2 SNPs rs7903146 and rs12255372 are strongly associated with reduced insulin secretion, possibly owing to impaired response to incretins [10, 11] and impaired beta cell function [10, 12, 13]. Accordingly, we tested the hypothesis that the efficacy response to linagliptin therapy, which acts via inhibition of incretin degradation, may be reduced in patients with type 2 diabetes who have high-risk TCF7L2 genotypes. It is possible that these individuals may be genetically predisposed to produce and secrete less incretin or have an impaired incretin response compared with those with wild-type genotype.

As expected, in the pooled analyses, the HbA1c levels of patients showed no change from baseline when administered placebo. In response to treatment with linagliptin, wild-type homozygous patients exhibited a robust −0.82% (−9.0 mmol/mol) reduction from baseline in HbA1c levels (p < 0.0001). In contrast, the response to treatment with linagliptin in patients who were homozygous for the risk allele was reduced (−0.57% [−6.2 mmol/mol] decrease from baseline in HbA1c on average; p < 0.0006), but still clinically meaningful (>0.5% [>5.5 mmol/mol] decrease).

Similar to the observations for HbA1c, homozygous wild-type patients treated with linagliptin showed a decrease in 2 h PPG levels compared with patients receiving placebo. Heterozygous patients exhibited a response similar to that observed for homozygous wild-type patients and homozygous risk carriers (TT) showed the least decrease from baseline in 2 h PPG levels. However, the number of patients in each of these groups was small and probably not sufficient to allow meaningful conclusions to be made.

The observed differences in linagliptin efficacy response of ~25% between TCF7L2 homozygous risk carriers (12% of whites) and non-risk carriers are in line with previous data of an association of TCF7L2 and sulfonylurea response [9]. This would support the recent postulation by Schäfer et al [28] that TCF7L2 variants are associated with a functional defect in the beta cells. Considering that the efficacy response to linagliptin in the TT carriers was clinically relevant, it is intriguing to speculate that a stronger loss of efficacy than that observed in this investigation would have been expected in homozygous carriers if a specific incretin-related defect was present. Based on present data, this cannot be ruled out. Another possibility for the lack of a more pronounced effect may be that polymorphisms in a single gene may not be sufficient to produce a significant change in a patient’s response to a DPP-4 inhibitor. Variants in additional genes could potentially contribute to inter-individual variability in response, and combined analyses of several risk genes for type 2 diabetes implicated in the regulation of beta cell function may further help explain the variability of efficacy response to insulin secretagogues.

The study has some limitations, mainly related to the relatively small sample size. This was addressed by combining the data from four clinical trials. However, we cannot completely rule out the influence of co-medication. The fact that we did observe the same trend for the differences in response to linagliptin treatment between CC wild-type and TT risk carriers by analysing each trial with different background therapies separately, supports our hypothesis. In addition, a disease–genetic process in TCF7L2 carriers could contribute to the effect, but the change in HbA1c level from baseline in the placebo groups did not reveal differences between CC and TT risk allele carriers, indicating a pharmacogenetic effect.

Nevertheless, results must be interpreted with some caution and should ideally be confirmed in a second cohort. Since linagliptin was the only DPP-4 inhibitor evaluated, it is unknown whether or not these observations are specific to linagliptin or whether they can be regarded as a class effect.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, these are the first studies testing the impact of TCF7L2 genotype on the response to incretin therapy (DPP-4 inhibitor) in a longitudinal cohort. Our analyses demonstrate for the first time that although the clinical response to the DPP-4 inhibitor linagliptin was somewhat attenuated in homozygous TCF7L2 risk carriers, this treatment results in a clinically meaningful glucose-lowering potency, even in homozygous high-risk allele carrier patients.

Abbreviations

- DPP-4:

-

Dipeptidylpeptidase-4

- PPG:

-

Postprandial plasma glucose

- SNP:

-

Single-nucleotide polymorphism

References

International Diabetes Federation (2011) IDF diabetes atlas. Available from www.idf.org/diabetesatlas, accessed 4 September 2012

Dupuis J, Langenberg C, Prokopenko I et al (2010) New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet 42:105–116

Frayling TM (2007) Genome-wide association studies provide new insights into type 2 diabetes aetiology. Nat Rev Genet 8:657–662

Voight BF, Scott LJ, Steinthorsdottir V et al (2010) Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nat Genet 42:579–589

Cauchi S, El Achhab Y, Choquet H et al (2007) TCF7L2 is reproducibly associated with type 2 diabetes in various ethnic groups: a global meta-analysis. J Mol Med (Berl) 85:777–782

Tong Y, Lin Y, Zhang Y et al (2009) Association between TCF7L2 gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to type 2 diabetes mellitus: a large Human Genome Epidemiology (HuGE) review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Genet 10:15

Grant SFA, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I et al (2006) Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 38:320–323

Helgason A, Palsson S, Thorleifsson G et al (2007) Refining the impact of TCF7L2 gene variants on type 2 diabetes and adaptive evolution. Nat Genet 39:218–225

Pearson ER, Donnelly LA, Kimber C et al (2007) Variation in TCF7L2 influences therapeutic response to sulfonylureas: a GoDARTs study. Diabetes 56:2178–2182

Lyssenko V, Lupi R, Marchetti P et al (2007) Mechanisms by which common variants in the TCF7L2 gene increase risk of type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest 117:2155–2163

Pilgaard K, Jensen CB, Schou JH et al (2009) The T allele of rs7903146 TCF7L2 is associated with impaired insulinotropic action of incretin hormones, reduced 24 h profiles of plasma insulin and glucagon, and increased hepatic glucose production in young healthy men. Diabetologia 52:1298–1307

Shu L, Matveyenko AV, Kerr-Conte J, Cho JH, McIntosh CH, Maedler K (2009) Decreased TCF7L2 protein levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus correlate with downregulation of GIP- and GLP-1 receptors and impaired beta-cell function. Hum Mol Genet 18:2388–2399

Shu L, Sauter NS, Schulthess FT, Matveyenko AV, Oberholzer J, Maedler K (2008) Transcription factor 7-like 2 regulates beta-cell survival and function in human pancreatic islets. Diabetes 57:645–653

Woerle HJ, Carneiro L, Derani A, Goke B, Schirra J (2012) The role of endogenous incretin secretion as amplifier of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in healthy subjects and patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 61:2349–2358

Drucker DJ, Nauck MA (2006) The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet 368:1696–1705

Forst T, Uhlig-Laske B, Ring A, Ritzhaupt A, Graefe-Mody U, Dugi KA (2011) The oral DPP-4 inhibitor linagliptin significantly lowers HbA1c after 4 weeks of treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab 13:542–550

Deacon CF, Holst JJ (2010) Linagliptin, a xanthine-based dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor with an unusual profile for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 19:133–140

Taskinen MR, Rosenstock J, Tamminen I et al (2011) Safety and efficacy of linagliptin as add-on therapy to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Obes Metab 13:65–74

Owens DR, Swallow R, Dugi KA, Woerle HJ (2011) Efficacy and safety of linagliptin in persons with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled by a combination of metformin and sulphonylurea: a 24-week randomized study. Diabet Med 28:1352–1361

Del Prato S, Barnett AH, Huisman H, Neubacher D, Woerle HJ, Dugi KA (2011) Effect of linagliptin monotherapy on glycaemic control and markers of beta-cell function in patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 13:258–267

Gomis R, Espadero RM, Jones R, Woerle HJ, Dugi KA (2011) Efficacy and safety of initial combination therapy with linagliptin and pioglitazone in patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Obes Metab 13:653–661

Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR (1977) DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 74:5463–5467

National Center for Biotechnology Information (2012) Database of single nucleotide polymorphisms (dbSNP). National Library of Medicine, Bethesda

Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M et al (2001) dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res 29:308–311

Jin T (2008) The WNT signalling pathway and diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 51:1771–1780

Jin T, Liu L (2008) The Wnt signaling pathway effector TCF7L2 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mol Endocrinol 22:2383–2392

Yi F, Sun J, Lim GE, Fantus IG, Brubaker PL, Jin T (2008) Cross talk between the insulin and Wnt signaling pathways: evidence from intestinal endocrine L cells. Endocrinology 149:2341–2351

Schäfer SA, Tschritter O, Machicao F et al (2007) Impaired glucagon-like peptide-1-induced insulin secretion in carriers of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene polymorphisms. Diabetologia 50:2443–2450

Funding

This study was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim, Germany. The authors were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions, were involved at all stages of manuscript development and approved the final version. Medical writing assistance, supported financially by Boehringer Ingelheim, was provided by M. Nori, Envision Scientific Solutions, Southport, CT, USA during the preparation of this manuscript.

Duality of interest

HZ, CI, UGM, MM, HJW and KAD are all employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. BOB declares that there is no duality of interest associated with his contribution to this manuscript.

Contribution statement

HZ participated in study design, researched data and participated in writing the manuscript. CI researched data, performed statistical analyses and reviewed and edited the manuscript. UGM participated in study design, researched data, contributed to the interpretation of the data and participated in writing the manuscript. BOB contributed to the study design and discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript. MM contributed to the discussion and interpretation of the data and reviewed and edited the manuscript. HJW participated in the study design, contributed to the discussion and interpretation of the data and reviewed and edited the manuscript. KAD initiated the scientific investigation, participated in the study design, contributed to the discussion and interpretation of the data and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors gave their approval to the final version of the manuscript. HZ is the guarantor of this work and as such, had full access to all the data in the study, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Table 1

(PDF 38 kb)

ESM Fig. 1

(PDF 292 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Zimdahl, H., Ittrich, C., Graefe-Mody, U. et al. Influence of TCF7L2 gene variants on the therapeutic response to the dipeptidylpeptidase-4 inhibitor linagliptin. Diabetologia 57, 1869–1875 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-014-3276-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-014-3276-y