Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Endothelial cells (ECs) and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) play key roles in the development of intimal hyperplasia in saphenous vein (SV) bypass grafts. In diabetic patients, insulin administration controls hyperglycaemia but cardiovascular complications remain. Insulin is synthesised as a pro-peptide, from which C-peptide is cleaved and released into the circulation with insulin; exogenous insulin lacks C-peptide. Here we investigate modulation of human SV neointima formation and SV-EC and SV-SMC function by insulin and C-peptide.

Methods

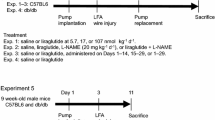

Effects of insulin and C-peptide on neointima formation (organ cultures), EC and SMC proliferation (cell counting), EC migration (scratch wound), SMC migration (Boyden chamber) and signalling (immunoblotting) were examined. A real-time RT–PCR array identified insulin-responsive genes, and results were confirmed by real-time RT–PCR. Targeted gene silencing (siRNA) was used to assess functional relevance.

Results

Insulin (100 nmol/l) augmented SV neointimal thickening (70% increase, 14 days), SMC proliferation (55% increase, 7 days) and migration (150% increase, 6 h); effects were abrogated by 10 nmol/l C-peptide. C-peptide did not affect insulin-induced Akt or extracellular signal-regulated kinase signalling (15 min), but array data and gene silencing implicated sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1 (SREBF1). Insulin (1–100 nmol/l) did not modify EC proliferation or migration, whereas 10 nmol/l C-peptide stimulated EC proliferation by 40% (5 days).

Conclusions/interpretation

Our data support a causative role for insulin in human SV neointima formation with a novel counter-regulatory effect of proinsulin C-peptide. Thus, C-peptide can limit the detrimental effects of insulin on SMC function. Co-supplementing insulin therapy with C-peptide could improve therapy in insulin-treated patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adults with diabetes have an increased prevalence of coronary heart disease compared with non-diabetic individuals [1–4]. Intensive control of hyperglycaemia retards diabetic microvascular complications (e.g. retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy) [5], but beneficial macrovascular effects (coronary atherosclerosis) are less apparent [6]. Long-term outcomes of revascularisation are disappointing, irrespective of the mode: angioplasty, stenting or coronary artery bypass grafting [1, 7, 8].

The autologous saphenous vein (SV) is used routinely as a conduit for coronary artery bypass grafts. Occlusions caused by intimal hyperplasia are common [9–11], with only ∼50% of grafts patent after 10 years and fewer in diabetic patients [12]. Implantation of the SV graft immediately exposes it to arterial pressure, with profound effects on endothelial cell (EC) and smooth muscle cell (SMC) biology. Loss of homeostatic regulation due to EC damage promotes SMC proliferation and migration in the graft wall, culminating in intimal hyperplasia and graft occlusion [13].

Insulin effectively controls blood glucose but can itself stimulate SMC proliferation and migration [14], increasing neointima formation in balloon-injured arteries of normal and diabetic rats [15–17]. Insulin also reportedly enhanced neointima formation in organ-cultured SV in tissue from five patients [18]. Insulin acting on SV-SMCs may therefore contribute to the pathogenesis of intimal hyperplasia in insulin-dependent diabetic patients.

Human proinsulin C-peptide is a 31-amino-acid peptide that links the A and B chains of proinsulin, ensuring its correct folding [19–21]. C-peptide is cleaved from proinsulin and released into the circulation with insulin in equimolar concentrations. Early studies reported no biological function of C-peptide [22], an observation supported by lack of interspecies conservation of the C-peptide sequence, both in chain length and amino acid composition. However, it is now apparent that human proinsulin C-peptide is biologically active and modulates cellular function [20]. Type 1 diabetic patients receive insulin therapy from an early stage, and the majority of type 2 patients over time also require insulin. Exogenously administered insulin does not contain C-peptide. Low sustained concentrations of C-peptide are beneficial [23–25], and chronic administration of replacement C-peptide with insulin ameliorates microvascular complications in animal models and type 1 diabetic patients [19, 20, 26]. A combination of insulin and C-peptide may therefore provide a more effective treatment for diabetic patients than insulin alone.

Here we explored the interplay between human insulin and proinsulin C-peptide on intimal hyperplasia in organ-cultured SVs from patients without diabetes and on the two key cell types involved in neointima formation, ECs and SMCs, to resolve their independent and joint cell-type-specific effects.

Methods

Materials

Cell culture reagents were purchased from Invitrogen (Paisley, UK), except FBS from LabTech International (Ringmer, UK). Proinsulin C-peptide, insulin and PDGF-BB were from Sigma (Poole, UK). PD98059 and LY294002 were from Calbiochem (Nottingham, UK). Migration assay chambers were from BD Biosciences (Oxford, UK).

Tissue and cell culture

Samples of SV and internal mammary artery (IMA) were obtained from non-diabetic patients undergoing elective coronary artery bypass grafting at the Leeds General Infirmary, with local ethical committee approval and informed patient consent. The study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2000. Organ cultures were performed using undistended SV as we have described previously [27] in the absence or presence of insulin, alone or with C-peptide. Segments were fixed and processed to 10 μm. Neointimal thickness was determined using computational analysis on high field magnification at 60 μm intervals along each section by two independent observers.

SMCs were cultured from human SV, IMA and aortic root by an explant technique as we have described previously [28]. SMCs were maintained at 37°C in DMEM containing 25 mmol/l glucose and 10% FBS in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. SV-ECs were harvested by collagenase digestion and cultured as described previously [29]. Experiments were performed on cells of passage number 2–6 from different patients.

Proliferation assays

SV-EC proliferation assays were performed by seeding cells from different patients in 24-well culture plates at a density of 10,000 per well in full endothelial growth medium (20% FBS). After 30–32 h incubation cells were quiesced in medium containing 1% FBS for 16 h. Cells were then exposed to control growth medium (1% or 10% FBS as appropriate) and selected concentrations of insulin, C-peptide or in combination. Medium and drugs were replaced on days 2 and 4 and viable cell number determined in triplicate wells on day 5 using Trypan Blue and a haemocytometer.

SV-SMC and IMA-SMC proliferation assays were performed essentially as described previously [28]. After plating (10,000 cells per well), cells were incubated overnight in full growth medium, then quiesced in serum-free medium for 3 days before transfer to control growth medium (DMEM with 0.2% FBS and 10 ng/ml platelet-derived growth factor) alone or with appropriate supplements (insulin and/or C-peptide). Medium and drugs were replaced on days 2 and 4 and viable cell number determined in triplicate wells on the appropriate day (usually day 7).

Migration assays

SV-EC migration was investigated in six-well plates using a modification of a ‘scratch wound’ method [30]. Briefly, duplicate scratches were made with a sterile 1 ml pipette tip in confluent endothelial monolayers, reference points etched in the dishes and images were captured (0 h). Cells were then exposed to the relevant media with appropriate stimuli in a tissue-culture incubator for an additional 24 h. Further images were then captured by aligning the dishes with the reference point made at time 0 h, and a second image acquired. Distances of each scratch closure were determined by measuring the cell-denuded area at equal intervals along the wound at each time point for each treatment condition.

SV-SMC migration was studied using a modified Boyden chamber technique, as we have described previously [28]. Cells (100,000) from different patients were loaded in the upper chamber in medium supplemented with 0.4% FBS. The lower chamber contained 0.4% FBS with appropriate supplements (insulin and/or C-peptide). After incubation for 6 h at 37°C in a tissue-culture incubator, duplicate membranes were processed and evaluated by counting migrated cells on the underside of the membrane in 10 random fields under high power (×400) light microscopy [28].

Immunoblotting

Serum-starved cells were exposed to serum-free medium containing insulin and/or C-peptide for 15 min before preparing whole cell homogenates and immunoblotting as described previously [31]. Phosphorylation of Akt (Ser473) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (Thr202/Tyr204) was determined using phospho-specific and expression antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Hitchin, UK). Immunolabelled bands were visualised by chemiluminescence and densitometric analysis performed as previously described [32].

PCR arrays

Serum-deprived SV-SMCs were exposed to 0.4% FBS alone or supplemented with 100 nmol/l insulin for 6 h before extracting RNA and performing first-strand cDNA synthesis [33]. The cDNA was confirmed to be of suitable quality for array analysis using the SuperArray QC PCR array (SABiosciences) and the ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System. Samples of cDNA were then analysed using the Insulin Signalling Pathway Array (SABiosciences). Cycle threshold (Ct) values were obtained using Sequence Detection Software SDS v1.2.3 (Applied Biosystems) and data analysed by comparing Ct values of 84 insulin pathway genes with those of five different housekeeping genes using the SuperArray PCR array analysis software (SABiosciences).

Real-time PCR

Real-time RT–PCR performed as described previously [33] using the ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System with the following human Taqman primer/probe sets: sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1 (SREBF1) (product number Hs01088691_m1), IGF 1 receptor (IGF1R) (Hs00541255_s1), sorbin and SH3 domain containing protein 1 (SORBS1) (Hs00908953_m1) and GLUT4 (Hs00168966_m1). Data were expressed as a percentage of hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT1) mRNA levels (Hs99999909_m1 primers) using the formula \(2^{{ - \Delta {\text{C}}_{{\text{t}}} }} \times 100\), or normalised to control sample using the formula \(2^{{ - \Delta \Delta {\text{C}}_{{\text{t}}} }}\).

SREBF1 gene silencing

SV-SMCs were transfected with a combination of four different SREBF1-targeted siRNA oligonucleotides (100 nmol/l) (SMARTPool; Dharmacon, Cramlington, UK) using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen), as described previously [34]. Control cells were transfected in the absence of siRNA (mock transfected). Effects on protein levels were determined by immunoblotting with mouse monoclonal anti-SREBF1 antibody (ab3259, Abcam), using the method described above. The effects of SREBF1 gene silencing on SV-SMC migration were determined 36 h after transfection.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means ± SEM, with n representing the number of experiments on cells/tissue from different patients. Data were analysed as ratios using repeated measures one-way ANOVA with the Newman–Keuls post hoc test, using GraphPad Prism software (www.graphpad.com). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Neointimal thickening in organ-cultured human SV

The ability of insulin to modulate neointima formation was investigated using organ-cultured human SV from ten different patients (Fig. 1). Mean neointima thickness was 10.4 ± 1.4 µm (median 11.7 µm, range 5.2–16.6 µm) after 14 days’ incubation and increased by 70% (p < 0.01) following supplementation with 100 nmol/l insulin (mean 17.7 ± 2.6 µm, median 16.7 µm, range 6.5–31.4 µm). Treatment of SV cultures with C-peptide (10 nmol/l) together with insulin (100 nmol/l) prevented the increase in neointima (mean 8.8 ± 1.36 µm, median 8.9 µm, range 4.8–15.5 µm).

Effect of insulin and C-peptide on neointimal thickness in organ-cultured human SV. SV segments were cultured for 14 days in 30% FBS alone (control) or supplemented with 100 nmol/l insulin and/or human C-peptide (10 nmol/l). a Representative sections of 14-day cultured segments, stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Scale bars, 30 μm. I, intima; M, media; NI, neointima. b Image analysis of full-length SV sections to calculate mean neointima thickness. Scatter plot shows individual values from ten different patients, with data from the same patients linked. ***p < 0.001 (n = 10)

Proliferation and migration of ECs promote re-endothelialisation of the damaged vessel wall, thereby limiting neointimal development. By contrast, SMC proliferation and migration contribute to neointimal development. We therefore investigated the effects of insulin and C-peptide on SV-EC and SV-SMC proliferation and migration.

Endothelial cell proliferation

Figure 2a shows SV-EC counts from ten different patients cultured in 10% FBS with no change in cell number in response to 1–100 nmol/l insulin after 5 days. Similarly, no effect of insulin was seen in cells exposed to 1% FBS (data not shown). When cells were exposed to C-peptide (10 nmol/l) alone, a significant increase in cell number of ∼40% was observed, which was not affected by insulin (Fig. 2b). Further studies revealed that C-peptide increased SV-EC proliferation at concentrations as low as 0.1 nmol/l (Fig. 2c).

Effect of insulin and C-peptide on human SV-EC proliferation and migration. a SV-EC proliferation. Quiesced cells treated with 10% FBS supplemented with 0–100 nmol/l insulin. Cells counted on day 0 and after 5 days with insulin and/or C-peptide treatment. ANOVA: p = 0.599 for effect of insulin on day 5 (n = 10). Post hoc: all non significant. b SV-EC proliferation. Medium supplemented with 10 nmol/l C-peptide alone or in combination with 1–100 nmol/l insulin for 5 days. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01 (n = 4). c SV-EC proliferation. Medium supplemented with 0.1–10 nmol/l C-peptide for 5 days. ANOVA: p < 0.001 for effect of C-peptide. Post hoc: **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 (n = 6). d SV-EC migration. Representative images of wounded endothelial cell monolayers in 10% FBS at 0 h and 24 h. Migration distances of SV-EC in 1% FBS (e) or 10% FBS (f) with insulin (100 nmol/l), C-peptide (10 nmol/l) or both (n = 4). ANOVA with post hoc: all NS

Endothelial cell migration

In the scratch wound assay, SV-ECs at the wound edge migrate to repopulate a denuded area created by the scratch (Fig. 2d). Cells exposed to 1% FBS (Fig. 2e) had half the migratory capacity of cells in 10% FBS (Fig. 2f). No modulatory effects were observed with either insulin, C-peptide or both together in either 1% or 10% FBS-supplemented media (Fig. 2e, f).

Smooth muscle cell proliferation

SV-SMCs from four different patients cultured in control growth medium exhibited a 2.5-fold increase in cell number after 7 days compared with day 0 (Fig. 3a). C-peptide did not affect cell number observed in the absence of insulin, but supplementation with 10–100 nmol/l insulin further increased SV-SMC proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner (ANOVA p < 0.0001), with 100 nmol/l insulin stimulating a 55% increase in cell number (Fig. 3a). These mitogenic effects of insulin were prevented by co-incubation with 10 nmol/l C-peptide (Fig. 3a). The mean number of detached cells observed throughout the proliferation assays was <1% of the total and was unaffected by any treatment (data not shown).

Effect of insulin and C-peptide on human SMC proliferation. Quiesced SMC incubated in medium containing 0.2% FBS + 10 ng/ml platelet-derived growth factor supplemented with insulin and/or C-peptide. Cells counted on day 0 (before additions) and after 7 days unless stated otherwise. a SV-SMCs exposed to 0–100 nmol/l insulin alone (white bars) or insulin together with 10 nmol/l C-peptide (black bars). ANOVA: p < 0.0001 for effect of insulin (***p < 0.001 post hoc); p = 0.3084 for effect of insulin + C-peptide (n = 4). †† p < 0.01, ††† p < 0.001 for effect of C-peptide in presence of insulin. b IMA-SMCs from the same patients as (a) exposed to 0–100 nmol/l insulin alone (white bars) or insulin together with 10 nmol/l C-peptide (black bars). ANOVA: p = 0.3743 for effect of insulin; p = 0.7783 for effect of insulin + C-peptide (n = 4). Post hoc: all NS. c SV-SMCs exposed to control basal medium (black squares) or basal medium supplemented with 100 nmol/l insulin (white squares) or 100 nmol/l insulin plus 10 nmol/l C-peptide (black circles) for 7 days. Cells counted on days 0–4 and 7. Area under curve analysis: control vs insulin, p < 0.01; control vs insulin + C-peptide, p > 0.05; insulin vs insulin + C-peptide, p < 0.05 (n = 4). d SV-SMCs exposed to 0–10 nmol/l C-peptide alone (white bars) or together with 50 nmol/l insulin (black bars). *p < 0.05; NS, not significant for effect of insulin (n = 4). e SV-SMCs exposed to medium supplemented without (white bars) or with (black bars) 100 nmol/l insulin in absence (‘control’) or presence of 10 nmol/l C-peptide or 10 nmol/l scrambled C-peptide. *p < 0.05 (n = 5). f Human aortic SMCs exposed to control basal medium (‘Ctrl’) or basal medium supplemented with 10 nmol/l C-peptide, 100 nmol/l insulin, or both together for 7 days. *p < 0.05 (n = 3)

IMA-SMCs cultured from the same four patients as the SV-SMCs, displayed a 2.1-fold increase in cell number after 7 days treatment in control growth medium (Fig. 3b), which was lower than that observed for SV-SMCs. In stark contrast to SV-SMCs, insulin (10–100 nmol/l) had no effect on IMA-SMC proliferation, and C-peptide (10 nmol/l) did not modulate proliferation in the presence or absence of insulin (Fig. 3b).

A time course of the effects of insulin and C-peptide on SV-SMC proliferation revealed that the mitogenic effects of insulin, and the attenuating effects of C-peptide, were evident over a 3–7 day period (Fig. 3c). Comparison of areas under the proliferation curves revealed that cells exposed to insulin proliferated at a higher rate than control cells (p < 0.01) or cells cultured in the presence of both insulin plus C-peptide (p < 0.05). There was no difference in proliferation rates between control cells and those cultured with insulin plus C-peptide. Further studies revealed that C-peptide attenuated insulin-induced SV-SMC proliferation at concentrations as low as 0.1 nmol/l (Fig. 3d). In contrast to C-peptide, a scrambled version of C-peptide (31-mer with the same amino acid content as C-peptide but in a random order) had no effect on proliferation of SV-SMCs in the absence or presence of insulin (Fig. 3e).

In view of C-peptide’s lack of effect on arterial vs venous SMCs, and a previous report that it increased aortic SMC proliferation in the absence of insulin [35], we investigated the effects of insulin and C-peptide on SMCs cultured from human aortic root (Fig. 3f). C-peptide increased proliferation of human aortic SMCs (35% increase) in agreement with Walcher et al. [35]. Insulin alone also stimulated a 28% increase in aortic SMC number. Insulin and C-peptide together showed no additive proliferative response compared with either agent alone (Fig. 3f), and scrambled C-peptide had no effect (data not shown).

Smooth muscle cell migration

SMC migration was assessed using Boyden chambers. A significant increase (2.5-fold) was observed in migration towards a 100 nmol/l insulin stimulus (Fig. 4a). Consistent with C-peptide’s effects on neointima formation and SV-SMC proliferation (Figs 1, 3), inclusion of 10 nmol/l C-peptide with insulin fully prevented insulin-induced migration of SV-SMCs (Fig. 4a, n = 11 patients). Pre-treatment with inhibitors of the ERK pathway (PD98059) or phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway (LY294002) fully prevented insulin-induced migration (Fig. 4b), indicating essential roles for these signalling pathways.

Effect of insulin and C-peptide on SV-SMC migration and signalling. a Migration of SV-SMCs from 11 patients towards basal medium (control), or medium supplemented with 100 nmol/l insulin alone, or 100 nmol/l insulin plus 10 nmol/l C-peptide. ***p < 0.001 (n = 11). b SV-SMC migration towards 100 nmol/l insulin stimulus following pretreatment with 30 μmol/l PD98059 (ERK pathway inhibitor) or 10 μmol/l LY294002 (PI3K/Akt pathway inhibitor). The bar chart depicts the mean number of migrated cells per high power (HP) field. ***p < 0.001 (n = 4). c, d SV-SMCs exposed to serum-free medium (SFM) alone or supplemented with 50 nmol/l insulin and/or 10 nmol/l C-peptide for 15 min before preparing homogenates and immunoblotting for phosphorylated and total Akt (c) or ERK (d). The bar charts depict densitometric ratios of phospho- to total Akt/ERK from five separate experiments. ***p < 0.001 (n = 5)

Smooth muscle cell signalling

We next investigated whether C-peptide could be acting by inhibiting the ERK or PI3K/Akt pathways, the two major pathways that lie downstream of the insulin receptor. Insulin stimulated phosphorylation of Akt (Fig. 4c), but ERK phosphorylation was not markedly increased, probably owing to the high basal level of ERK activation in these cells (Fig. 4d). C-peptide alone or in combination with insulin did not modulate Akt or ERK signalling (Fig. 4c,d). Thus, C-peptide ablates the effects of insulin on SV-SMC function independently of ERK or Akt signalling pathways.

Smooth muscle cell gene expression

To identify insulin-responsive genes modulated by C-peptide, we used a SYBR-Green-based real-time RT–PCR array to monitor expression of 84 genes involved in insulin signalling, including insulin-receptor-associated proteins, components of the ERK and Akt pathways, insulin-responsive genes, transcription factors and genes involved in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. SV-SMCs from six patients were treated with or without 100 nmol/l insulin for 6 h before extracting RNA. Concomitant migration assays were performed to confirm the functional effects of insulin and C-peptide on SV-SMC migration (Fig. 5a).

Effect of insulin and C-peptide on SV-SMC gene expression. a SV-SMC migration towards 100 nmol/l insulin in the absence or presence of C-peptide (10 nmol/l). ***p < 0.001 (n = 6). b SV-SMC from the same six patients with 100 nmol/l insulin for 6 h before extracting RNA and performing PCR array. Data expressed as volcano plot in which the x-axis depicts changes in mRNA levels (increases to the right of the origin, decreases to the left), and y-axis depicts statistical significance. Full data are available as ESM (Table 1). c, d Real-time RT–PCR data of SREBF1 or IGF1R mRNA levels following 6 h treatment of SV-SMCs with 100 nmol/l insulin alone or together with 10 nmol/l C-peptide as percentage of HPRT1 housekeeping gene mRNA levels. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (n = 6). e, f Real-time RT–PCR of SREBF1 or IGF1R mRNA levels following 1–6 h treatment of SV-SMC with 100 nmol/l insulin alone (white bars) or together with 10 nmol/l C-peptide (black bars) (n = 3). Data are expressed relative to HPRT levels and normalised to 0 h sample. SREBF ANOVA: p = 0.004 for effect of insulin alone (*p < 0.05 post hoc); p = 0.713 for effect of insulin + C-peptide. + p < 0.05 for effect of C-peptide in presence of insulin. IGFR1 ANOVA: p = 0.018 for effect of insulin alone (*p < 0.05 post hoc); p = 0.026 for effect of insulin + C-peptide (*p < 0.05 post hoc). There was no significant effect of C-peptide in the presence of insulin

Data are presented in Fig. 5b as a volcano plot with full data included in the Electronic supplementary material (ESM) Table 1. We selected four genes for further study based on changes in transcript levels and reproducibility (statistical significance): namely IGF1R, SORBS1, GLUT4 and SREBF1.

Taqman primer/probe sets were utilised to confirm array data using the same RNA samples. The insulin-induced increase in SREBF1 mRNA expression and decrease in IGF1R mRNA expression were confirmed by RT–PCR (Fig. 5c,d). However, the array data could not be confirmed for SORBS1 or GLUT4 (data not shown).

Insulin-induced SREBF1 mRNA expression was fully prevented by co-incubation with C-peptide (Fig. 5c). By contrast, the effect of insulin on IGF1R expression was not modulated by C-peptide (Fig. 5d). The acute temporal profiles of SREBF1 and IGF1R mRNA expression in response to insulin, with or without C-peptide, were then determined over the 6 h period (Fig. 5e,f). Insulin-induced SREBF1 mRNA expression was evident after 3 h and rose thereafter, reaching a 40% increase after 6 h (ANOVA, p < 0.01) (Fig. 5e). No increase in SREBF1 mRNA levels was apparent when C-peptide was present with insulin (ANOVA, p = 0.713) (Fig. 5e). In contrast to SREBF1, the insulin-induced decrease in IGF1R mRNA expression after 2–6 h (ANOVA, p < 0.05) was not modulated by C-peptide (Fig. 5f).

Effect of SREBF1 gene silencing on SV-SMC migration

The above data implicated SREBF1 as a molecular target for the antagonistic effects of C-peptide on insulin-induced SV-SMC proliferation and migration. To confirm that SREBF1 expression was involved in insulin-induced SV-SMC migration, we employed a gene-silencing approach. SREBF1 protein production was markedly reduced 24–72 h following siRNA transfection, although a return of production was evident at the 96 h time point (Fig. 6a). SREBF1 gene silencing had no effect on basal SV-SMC migration but specifically prevented insulin-induced migration, to a level comparable with the inhibition achieved with C-peptide (Fig. 6b). SREBF1 knockdown had no modulatory effect on insulin-induced cell migration in the presence of C-peptide, suggesting that C-peptide and SREBF1 siRNA may be acting on the same target i.e. reducing SREBF1 expression. Thus, insulin-induced SV-SMC migration requires SREBF1 expression, and the ability of C-peptide to prevent insulin-induced migration may be explained through a reduction in SREBF1 expression.

Effect of SREBF1 gene silencing on insulin-induced SV-SMC migration. Cells were mock-transfected or transfected with SREBF1-targeted siRNA before measuring SREBF1 protein and SV-SMC migration. a Immunoblot showing SREBF1 protein production 24–96 h after transfection with or without SREBF1 siRNA. The arrow indicates the position of the SREBF1 band (125 kDa). b Migration assay showing effects of SREBF1 gene silencing (36 h) on SV-SMC migration towards basal medium (control; white bars), or medium supplemented with 100 nmol/l insulin alone (black bars) or together with 10 nmol/l C-peptide (hatched bars). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (n = 6)

Discussion

The principal finding of our study was that neointima formation in organ-cultured human SVs was increased in the presence of insulin, an effect abrogated by proinsulin C-peptide. Neointima formation requires SMC migration and proliferation, both of which were induced by insulin and fully inhibited by C-peptide. The effects of C-peptide were not a result of inhibition of insulin-mediated Akt and ERK signalling, but were related to reduced insulin-induced SREBF1 expression.

In agreement with earlier studies [15, 18] we revealed a causative role for insulin in neointima formation but importantly demonstrated a counter-regulatory effect of C-peptide. Our model mimics the situation of insulin-treated diabetes, with the presence of insulin but not C-peptide, and suggests that co-supplementing insulin with C-peptide could provide a better treatment than insulin alone.

Damage to the SVs during harvesting and implantation inevitably induces endothelial dysfunction, a feature associated with neointima formation. As effective re-endothelialisation is known to inhibit neointimal hyperplasia [36], we investigated whether insulin and/or C-peptide could modulate EC migration and/or proliferation. Insulin did not alter EC proliferation, whereas C-peptide induced an increase, an effect maintained in the presence of insulin. Migration was not affected by either insulin or C-peptide. Thus, C-peptide acts directly on SMCs to prevent neointima formation while increasing EC proliferation to promote re-endothelialisation [36].

In agreement with a previous study [37], insulin increased migration of SV-SMCs via ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways. However, C-peptide’s counter-regulation was not due to inhibition of these pathways. The mode of action of C-peptide is unknown, although it binds to human cell membranes [38] and its target may be a G-protein-coupled receptor in some tissues [39]. C-peptide has been shown to internalise in Swiss 3T3 and HEK 293 cells [40], and a very recent study in human aortic ECs and umbilical artery SMCs indicated that C-peptide was internalised by early endosomes [41]. Whether the endosomal pathway is functional in human SV-SMCs and required for C-peptide trafficking will require elucidation in future studies. Importantly, our data do not support speculation that C-peptide binds to the insulin receptor [42]. Thus, in human SV-SMCs, C-peptide acts independently of the insulin receptor and its immediate downstream signalling pathways.

Insulin increased SV-SMC proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner. C-peptide even at very low concentration abolished these effects, consistent with its activity at nanomolar concentrations found in plasma [43] and full saturation of C-peptide binding sites at low nanomolar concentrations [38].

In the vasculature, the reported effects of C-peptide are at variance and potentially explained by different experimental approaches. Two previous studies have claimed that C-peptide reduces SMC proliferation. One report used rat SMCs and human C-peptide and saw a modest effect on high glucose-induced (25 mmol/l) proliferation, but only after 3 weeks [44]. A more recent study using human arterial SMCs also observed increased proliferation with high glucose culture that was attenuated by C-peptide [45]. By contrast, our data differ from those reporting a mitogenic effect of C-peptide on human and rat aortic SMCs [35], in which C-peptide was coupled to activation of PI3K/Akt and ERK pathways, which were not modulated by C-peptide in our study using SV-SMCs. This raises the intriguing possibility that C-peptide has opposing effects on SMCs from different vascular beds. To test this, we cultured human aortic SMCs and found that C-peptide was pro-proliferative, in agreement with the findings of Walcher et al. [35]. However, when aortic SMCs were cultured in the presence of insulin, itself a mitogen, no additive effect of C-peptide was observed. Unlike our present study, in none of the above studies was the effect of insulin investigated. It is also important to note that in individuals without diabetes C-peptide is only ever present with insulin. The findings of all these reports can therefore be reconciled by taking into account species and source of SMCs, together with insulin, C-peptide and glucose concentrations.

In contrast to the SVs, IMA grafts provide better long-term patency even in diabetic patients [46], indicating resistance to restenosis. This remarkable difference in patency between conduits is clearly multifactorial, but we have previously shown that SV-SMCs are inherently more proliferative than IMA-SMCs from the same patients [32]. In direct contrast to SV cells, insulin did not promote IMA-SMC proliferation, which may help explain the similar patency rates of IMA grafts in insulin-treated patients compared with those in non-diabetic patients [46]. The inability of insulin to induce IMA-SMC proliferation was not due to lack of insulin signalling, as both Akt and ERK phosphorylation were evident in insulin-treated IMA-SMCs (data not shown). These data highlight the importance of using relevant cell types and add to the concept of cell-type-specific effects of both insulin and C-peptide.

Having established the effects of insulin and C-peptide on SV-SMC migration and proliferation, we used an insulin signalling array to identify potential molecular mechanisms. SREBF1 mRNA expression was increased in response to insulin; an effect attenuated by C-peptide. SREBF1 gene silencing selectively attenuated the insulin-induced component of SV-SMC migration, strongly suggesting that the ability of C-peptide to reduce SV-SMC migration is due to inhibition of insulin-induced SREBF1 expression. SREBF1 (SREBP1) is a member of the basic helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper (bHLH-Zip) family of transcription factors that regulate lipid and carbohydrate metabolism [47]. A role for SREBF1 in proliferation of murine aortic SMCs is reported [48]. SREBF1, by regulating lipid and cholesterol biosynthesis, may play a role in plasma membrane synthesis and could optimise membrane properties for SV-SMC migration and proliferation in response to insulin. Importantly, these effects of insulin can be abrogated by C-peptide.

Vascular SMC proliferation is induced by a plethora of growth factors and cytokines, and additionally hyperinsulinaemia has been implicated as an important risk factor for atherosclerotic lesion formation in diabetic patients through increased SMC proliferation [49]. Here we have shown that insulin and its C-peptide differ in their effects on cells from different vascular beds. These peptides are normally secreted in equimolar amounts but this relationship is perturbed when exogenous, recombinant insulin is administered to replace natural synthesis.

A potential limitation of our study was the use of 100 nmol/l insulin: a supraphysiological concentration when compared with that observed in vivo after a meal in normal (∼0.3–0.4 nmol/l) or insulin-resistant (∼1.4–1.5 nmol/l) individuals. Relatively high concentrations of insulin are often required in vitro to observe functional effects, probably reflecting the numerous differences between in-vitro functional assays and the situation in vivo. Lower concentrations of insulin (e.g. 25 nmol/l) also resulted in increased SV-SMC proliferation in our experiments (Fig. 3a), but we selected the 100 nmol/l concentration based on the reproducibility and magnitude of its effects. One strength of our study was the use of cells from multiple patients. Interestingly, C-peptide had maximal effects on SV-EC and SV-SMC proliferation at concentrations as low as 0.1 nmol/l (Figs 2c, 3d): levels of C-peptide that are physiologically relevant.

During the last decade there has been a wealth of new information regarding the impact of C-peptide on a variety of cell types and specific cell functions. However, until recently the major focus has been on the microvascular complications of type 1 diabetes [50], with its effects in type 2 diabetes being less well explored. It is generally perceived that C-peptide is beneficial (for reviews see [51, 52]), although the mechanisms underlying such effects appear to be tissue- and cell-type specific, and insulin is not always necessary for C-peptide to function. Indeed, our own data, for example, indicate a differential effect of C-peptide on SMCs from aorta and SV. In this respect, elucidation of the specific mechanisms underlying the functional effects of C-peptide in relevant cell types is of key importance.

In summary, our study is the first to report a direct modulatory effect of proinsulin C-peptide on the potentially deleterious effects of insulin on human SV neointima formation, through effects on both SMC and EC function. Our data implicate SREBF1 as a candidate for further investigation. Co-administration of C-peptide with insulin may improve SV bypass graft patency rates in insulin-treated diabetic patients. Clinical trials will be necessary to test this hypothesis.

Abbreviations

- EC:

-

Endothelial cell

- ERK:

-

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- HPRT1:

-

Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1

- IGF1R:

-

IGF 1 receptor

- IMA:

-

Internal mammary artery

- PI3K:

-

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- SMC:

-

Smooth muscle cell

- SORBS1:

-

Sorbin and SH3 domain containing protein 1

- SREBF1:

-

Sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1

- SV:

-

Saphenous vein

References

Hakala T, Pitkanen O, Halonen P, Mustonen J, Turpeinen A, Hippelainen M (2005) Early and late outcome after coronary artery bypass surgery in diabetic patients. Scand Cardiovasc J 39:177–181

Ledru F, Ducimetiere P, Battaglia S et al (2001) New diagnostic criteria for diabetes and coronary artery disease: insights from an angiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol 37:1543–1550

Herlitz J, Brandrup-Wognsen G, Caidahl K et al (1997) Mortality and morbidity among patients who undergo combined valve and coronary artery bypass surgery: early and late results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 12:836–846

Stone PH, Muller JE, Hartwell T et al (1989) The effect of diabetes mellitus on prognosis and serial left ventricular function after acute myocardial infarction: contribution of both coronary disease and diastolic left ventricular dysfunction to the adverse prognosis. The MILIS Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol 14:49–57

Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY et al (2005) Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 353:2643–2653

Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T et al (2009) Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 360:129–139

Cutlip DE, Chauhan MS, Baim DS et al (2002) Clinical restenosis after coronary stenting: perspectives from multicenter clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 40:2082–2089

Kornowski R, Mintz GS, Kent KM et al (1997) Increased restenosis in diabetes mellitus after coronary interventions is due to exaggerated intimal hyperplasia. A serial intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation 95:1366–1369

Gitman MR, Okrainec K, Nguyen H et al (2005) Impact of diabetes on 12-month outcomes following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: results from the ROSETTA–CABG Registry. Can J Cardiol 21:1169–1174

Lorusso R, Pentiricci S, Raddino R et al (2003) Influence of type 2 diabetes on functional and structural properties of coronary artery bypass conduits. Diabetes 52:2814–2820

Thourani VH, Weintraub WS, Stein B et al (1999) Influence of diabetes mellitus on early and late outcome after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg 67:1045–1052

Suma H (1999) Arterial grafts in coronary bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 5:141–145

Wallitt EJ, Jevon M, Hornick PI (2007) Therapeutics of vein graft intimal hyperplasia: 100 years on. Ann Thorac Surg 84:317–323

Forsyth EA, Aly HM, Najjar SF, Neville RF, Sidawy AN (1997) Transforming growth factor beta 1 inhibits the proliferative effect of insulin on human infragenicular vascular smooth muscle cells. J Vasc Surg 25:432–436

Foster E, Zhang S, Kahn AM (2006) Insulin stimulates arterial neointima formation in normal rats after balloon injury. Diabetes Obes Metab 8:348–351

Indolfi C, Torella D, Cavuto L et al (2001) Effects of balloon injury on neointimal hyperplasia in streptozotocin-induced diabetes and in hyperinsulinemic nondiabetic pancreatic islet-transplanted rats. Circulation 103:2980–2986

Park SH, Marso SP, Zhou Z, Foroudi F, Topol EJ, Lincoff AM (2001) Neointimal hyperplasia after arterial injury is increased in a rat model of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Circulation 104:815–819

Huang B, Dreyer T, Heidt M et al (2002) Insulin and local growth factor PDGF induce intimal hyperplasia in bypass graft culture models of saphenous vein and internal mammary artery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 21:1002–1008

Wahren J (2004) C-peptide: new findings and therapeutic implications in diabetes. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 24:180–189

Wahren J, Shafqat J, Johansson J, Chibalin A, Ekberg K, Jornvall H (2004) Molecular and cellular effects of C-peptide—new perspectives on an old peptide. Exp Diabesity Res 5:15–23

Hoffman M (1997) Connecting peptide, correcting peptide? Ann Intern Med 127:1147–1148

Kitabchi AE (1977) Proinsulin and C-peptide: a review. Metabolism 26:547–587

Sjoberg S, Gunnarsson R, Gjotterberg M, Lefvert AK, Persson A, Ostman J (1987) Residual insulin production, glycaemic control and prevalence of microvascular lesions and polyneuropathy in long-term type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 30:208–213

Sjoberg S, Gjotterberg M, Berglund L, Moller E, Ostman J (1991) Residual C-peptide excretion is associated with a better long-term glycemic control and slower progress of retinopathy in type I (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. J Diabet Complications 5:18–22

Zerbini G, Mangili R, Luzi L (1999) Higher post-absorptive C-peptide levels in type 1 diabetic patients without renal complications. Diabet Med 16:1048

Joshua IG, Zhang Q, Falcone JC, Bratcher AP, Rodriguez WE, Tyagi SC (2005) Mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction with development of type 1 diabetes mellitus: role of insulin and C-peptide. J Cell Biochem 96:1149–1156

Porter KE, Varty K, Jones L, Bell PR, London NJ (1996) Human saphenous vein organ culture: a useful model of intimal hyperplasia? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 11:48–58

Porter KE, Naik J, Turner NA, Dickinson T, Thompson MM, London NJ (2002) Simvastatin inhibits human saphenous vein neointima formation via inhibition of smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration. J Vasc Surg 36:150–157

Aley PK, Porter KE, Boyle JP, Kemp PJ, Peers C (2005) Hypoxic modulation of Ca2+ signaling in human venous endothelial cells. Multiple roles for reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem 280:13349–13354

Liang CC, Park AY, Guan JL (2007) In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat Protoc 2:329–333

Turner NA, Ball SG, Balmforth AJ (2001) The mechanism of angiotensin II-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 activation is independent of angiotensin AT1A receptor internalisation. Cell Signal 13:269–277

Turner NA, Ho S, Warburton P, O'Regan DJ, Porter KE (2007) Smooth muscle cells cultured from human saphenous vein exhibit increased proliferation, invasion, and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in vitro compared with paired internal mammary artery cells. J Vasc Surg 45:1022–1028

Turner NA, Mughal RS, Warburton P, O'Regan DJ, Ball SG, Porter KE (2007) Mechanism of TNFa-induced IL-1a, IL-1b and IL-6 expression in human cardiac fibroblasts: effects of statins and thiazolidinediones. Cardiovasc Res 76:81–90

Turner NA, Hall KT, Ball SG, Porter KE (2007) Selective gene silencing of either MMP-2 or MMP-9 inhibits invasion of human saphenous vein smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis 193:36–43

Walcher D, Babiak C, Poletek P et al (2006) C-Peptide induces vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation: involvement of SRC-kinase, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2. Circ Res 99:1181–1187

Tanous D, Brasen JH, Choy K et al (2006) Probucol inhibits in-stent thrombosis and neointimal hyperplasia by promoting re-endothelialization. Atherosclerosis 189:342–349

Wang CC, Gurevich I, Draznin B (2003) Insulin affects vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype and migration via distinct signaling pathways. Diabetes 52:2562–2569

Rigler R, Pramanik A, Jonasson P et al (1999) Specific binding of proinsulin C-peptide to human cell membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:13318–13323

Al Rasheed NM, Meakin F, Royal EL et al (2004) Potent activation of multiple signalling pathways by C-peptide in opossum kidney proximal tubular cells. Diabetologia 47:987–997

Lindahl E, Nyman U, Melles E et al (2007) Cellular internalization of proinsulin C-peptide. Cell Mol Life Sci 64:479–486

Luppi P, Geng X, Cifarelli V, Drain P, Trucco M (2009) C-peptide is internalised in human endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells via early endosomes. Diabetologia 52:2218–2228

Grunberger G, Qiang X, Li Z et al (2001) Molecular basis for the insulinomimetic effects of C-peptide. Diabetologia 44:1247–1257

Wahren J, Ekberg K, Johansson J et al (2000) Role of C-peptide in human physiology. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 278:E759–E768

Kobayashi Y, Naruse K, Hamada Y et al (2005) Human proinsulin C-peptide prevents proliferation of rat aortic smooth muscle cells cultured in high-glucose conditions. Diabetologia 48:2396–2401

Cifarelli V, Luppi P, Tse HM, He J, Piganelli J, Trucco M (2008) Human proinsulin C-peptide reduces high glucose-induced proliferation and NF-kappaB activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis 201:248–257

Influence of diabetes on 5-year mortality and morbidity in a randomized trial comparing CABG and PTCA in patients with multivessel disease: the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI) (1997) Circulation 96:1761–1769

Raghow R, Yellaturu C, Deng X, Park EA, Elam MB (2008) SREBPs: the crossroads of physiological and pathological lipid homeostasis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 19:65–73

Zhou RH, Pesant S, Cohn HI, Eckhart AD (2008) Enhanced sterol response element-binding protein in postintervention restenotic blood vessels plays an important role in vascular smooth muscle proliferation. Life Sci 82:174–181

Despres JP, Lamarche B, Mauriege P, Cantin B, Lupien PJ, Dagenais GR (1996) Risk factors for ischaemic heart disease: is it time to measure insulin? Eur Heart J 17:1453–1454

Wahren J, Sima AA (2009) C-peptide is relevant in type 1 diabetes and its complications: summary and conclusions to the special issue. Rev Diabet Stud 6:223–224

Hills CE, Brunskill NJ (2009) Cellular and physiological effects of C-peptide. Clin Sci (Lond) 116:565–574

Nordquist L, Wahren J (2009) C-Peptide: the missing link in diabetic nephropathy? Rev Diabet Stud 6:203–210

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge funding from The British Heart Foundation and the University of Leeds, UK. S.G. Ball is a British Heart Foundation Professor of Cardiology. N.A. Turner is the recipient of a Research Councils UK Academic Fellowship. We are grateful to J. Kaye and C. Bauer for cell culture expertise.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Table 1

(XLS 44 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mughal, R.S., Scragg, J.L., Lister, P. et al. Cellular mechanisms by which proinsulin C-peptide prevents insulin-induced neointima formation in human saphenous vein. Diabetologia 53, 1761–1771 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-010-1736-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-010-1736-6