Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Polymorphisms of the butyrylcholinesterase gene (BCHE) are reported to associate with Alzheimer’s disease and a recent study found a significant association of the BCHE K variant (G1615A/Ala539Thr) with Type 2 diabetes. The objectives of our study were to examine whether the BCHE K variant is associated with Type 2 diabetes or estimates of pancreatic beta cell function in large-scale populations of glucose-tolerant Caucasians.

Methods

The variant was genotyped in association studies comprising a total of 1408 Type 2 diabetic patients and 4935 glucose-tolerant control subjects. Genotype–phenotype studies were carried out in the 4935 glucose-tolerant control subjects.

Results

There was no difference in allele frequency between Type 2 diabetic patients and control subjects (20.3% [95% confidence interval: 18.8–21.8] vs 20.4% [19.6–21.2], non-significant). In the genotype–phenotype studies we found no consistent association with BMI, fasting or post-OGTT plasma glucose, serum insulin or serum C-peptide levels.

Conclusions/interpretation

The present study does not support the suggestion that the BCHE K polymorphism is associated with Type 2 diabetes or with estimates of pancreatic beta cell function in large-scale Danish Caucasian populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amyloid fibrils formed from pancreatic islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) may be present in more than 90% of cases of Type 2 diabetes [1]. Little is known about the molecular mechanisms causing the change of the monomeric, soluble IAPP form to insoluble refolded fibrils. Severe islet amyloidosis is correlated with the need for insulin therapy, loss of islet beta cells and may affect up to 80% of islets of Type 2 diabetic patients [1]. Amyloid fibrils cause excessive production of superoxide radicals, lipid peroxidation and nitric oxide inactivation, all of which may contribute to beta cell apoptosis [1]. The huge variation in pancreatic islet amyloid production and disposition is, however, not explained by variations in IAPP [1, 2].

Cytotoxic effects similar to those of pancreatic beta cell amyloid fibrils have been seen with fibrils formed from the amyloid peptide that occurs in Alzheimer’s disease, and indeed, deposition of amyloid plaques in the brain of Alzheimer patients is a characteristic histopathological feature [1, 3, 4]. The mechanisms of fibril-induced toxicity, both in Alzheimer’s disease and in Type 2 diabetes, involve interaction between the cell membranes and mis-folded insoluble peptides. It is therefore possible that these molecular processes share common regulatory elements [1].

The BCHE gene (3q26) is expressed in many tissues including white adipose tissue, liver, brain and pancreas [5, 6] and may have a direct biological impact on the pathogenesis of the amyloidosis related to Alzheimer’s disease [7]. Several variants have been identified in BCHE, the most common being a point mutation at nucleotide 1615 (GCA to ACA) predicting an alanine to threonine substitution at codon 539 [8, 9]. In the pertinent literature, this BCHE polymorphism, which has an allelic frequency of about 20% among Caucasians, is often termed the K variant. This variant is associated with a 30% reduction of the catalytic activity of the secreted and circulating BCHE protein [8] and has a high propensity for beta sheet formation, which may be related to amyloidogenesis [10, 11]. It is thus of interest that studies have shown an association between the codon 539 threonine allele and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease [12, 13, 14].

As reasoned above, BCHE is also a plausible biological candidate gene in the pathogenesis of the common and probably polygenic forms of Type 2 diabetes. Moreover, a locus on chromosome 3q27 has been linked to Type 2 diabetes in a French population [15]. The objectives of the present study were to elucidate whether the widespread and functional K polymorphism of BCHE is associated in large groups of Danish Caucasians with Type 2 diabetes or altered insulin secretion in response to oral glucose.

Subjects, materials and methods

Subjects

Genotyping of the K variant was performed in two separate studies.

The first study involved a group of unrelated Type 2 diabetic patients recruited at Steno Diabetes Center and a group of unrelated normal glucose-tolerant (NGT) subjects randomly sampled between 1994 and 1997 at Steno Diabetes Center and Research Centre for Prevention and Health [16]. In the group of Type 2 diabetic patients (n=809, 496 men, 313 women), the median age was 62 years (interquartile range: 53–69), the age of clinical diagnosis 55 years (48–63), BMI 28.0 kg/m2 (25.4–31.6) and HbA1c 7.9% (6.8–9.1). These patients were treated with diet alone (27%), with oral hypoglycaemic agents (OHA) (58%), or with insulin alone or in combination with OHA (15%). In the group of NGT participants (n=511, 239 men, 272 women) the age was 60 years (52–61) and BMI 25.1 kg/m2 (23.2–27.6).

The second study involved a population-based group of unrelated NGT subjects sampled at Research Centre for Prevention and Health [17] and a group of unrelated Type 2 diabetic patients recruited at Steno Diabetes Center and Research Centre for Prevention and Health [16, 17]. In the group of Type 2 diabetic patients (n=599, 338 men, 261 women) the median age was 55 years (46–60), age of diagnosis 53 years (45–60), BMI 29.1 kg/m2 (26.1–32.9), and HbA1c 6.5% (6.0–7.5). Treatment of these patients was: by diet alone (26%), with OHA (20%), or with insulin alone or in combination with OHA (12%). For 248 (42%) of the patients, diabetes was diagnosed upon examination for inclusion in this study, and they were therefore not receiving any treatment. In the group of NGT participants (n=4424, 2052 men, 2372 women) the median age was 45 years (40–50), BMI 25.0 kg/m2 (22.7–27.6) and 14.5% had a family history of Type 2 diabetes.

In both studies we performed case–control studies as well as genotype–phenotype studies in the NGT subjects. Diabetes was diagnosed according to 1999 WHO criteria [18]. All control subjects underwent a standard 75-g OGTT. All participants were Danish Caucasians by self-report. Informed written consent was obtained before participation. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Copenhagen and was in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki II.

Biochemical assays

Blood samples were drawn after a 12-h overnight fast and plasma glucose, serum-specific insulin levels, serum C-peptide, and HbA1c were measured using Steno Diabetes Center routine methods [17, 19].

Genotyping

In the first study, the BCHE K variant was genotyped using restriction site generating PCR-RFLP analysis with forward primer 5′-AAG TGG GTC AAG AAA AGA GCA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TGC TTT CCA CTC CCA TTC AG-3′ (mismatched nucleotide underlined). PCR amplification was carried out in a volume of 25 µl with 2 mmol/l MgCl2 and annealing at 57 °C, followed by digestion with AluI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass., USA). In the second study genotyping was performed using a chip-based matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry (DNA MassARRAY) of PCR-generated primer extension products as described [20]. The genotyping success rates of the RFLP-based method and the mass-spectrometry-based method were 97% and 96% respectively. Genotyping 10% of the study participants with any of the two genotyping methodologies resulted in an error rate of less than 0.5%.

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test was applied to examine differences in allele frequencies and genotype distributions between diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. A general linear model was used to test variables (or transformed variables) for differences between genotype groups in the two samples of unrelated NGT subjects. Genotype and sex were considered as fixed factors and age and BMI as covariates. All phenotype analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS, Chicago, Ill., USA) version 11.5. A two-sided p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Results of both case-control studies were combined by logistic regression using RGui version 1.7.0 (http://mirrors.sunsite.dk/cran/), which was also used for the power calculation (power.prop.test method).

Results

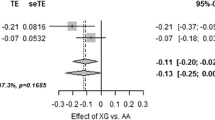

In the two separate case-control studies of association of the BCHE K variant with Type 2 diabetes, genotypes were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. No difference in genotype distribution or allele frequency was found in either of the studies (Table 1). Combined analysis of 1408 Type 2 diabetic patients and 4935 glucose-tolerant subjects was performed and yielded no difference in genotype distribution (p=1.0). In a simple combination of allele frequencies from the two studies there was also no significant difference between Type 2 diabetic patients and glucose-tolerant control subjects (20.3% [95% CI: 18.8–21.8] vs 20.4% [19.6–21.2] respectively, p=0.9). When we combined the oldest control subjects from both studies (1408 sex-matched NGT subjects, median age 55 years [interquartile range: 55–60]) and compared them with the total number of diabetic patients, this yielded a similar non-significant result (data not shown). We also did sub-stratification according to sex, age at diabetes diagnosis, BMI below or equal to and above 30 kg/m2, or insulin requirement. However, this, too, failed to reveal significant associations between subsets of Type 2 diabetes and BCHE genotypes (data not shown).

In the initial genotype–phenotype study (study 1) we showed no significant association of the K polymorphism with fasting or post-OGTT plasma glucose, serum insulin or serum C-peptide levels (Table 2). Applying a recessive model of inheritance, we demonstrated that homozygous carriers of the variant had a higher BMI. Thus, in the 20 glucose-tolerant subjects who were homozygous carriers of the Thr-allele we found a median BMI of 28.1 kg/m2 (interquartile range: 25.8–29.8) versus 25.1 kg/m2 (23.2–27.6) in 491 glucose-tolerant subjects who were either wild-type or heterozygous for the Thr-allele (p=0.03). However, in study 2 we failed to replicate an association between the K variant and increased BMI (Table 3). The genotype–phenotype studies were also stratified according to sex and BMI; however, the analyses in the subgroups did not show any significant genotype–phenotype associations (data not shown). Moreover, in a subset of 248 screen-detected Type 2 diabetic patients the Thr-allele frequency was 19.2% (95% CI: 15.7–22.6), a value that was similar to the frequency observed in the remaining diabetic patients.

Discussion

In the present large-scale studies we were unable to show evidence for a significant association between the functional amino acid polymorphism at codon 539 of BCHE and Type 2 diabetes in the Danish population. This was also the case when the group of diabetic patients were sub-stratified according to sex, age of clinical diabetes onset, BMI, or need of insulin therapy. The present findings are in contrast to a recent British study involving 276 Type 2 diabetic subjects and 348 non-diabetic subjects; however, the latter subjects were not classified according to their response to a standardised OGTT [21, 22]. In the British study, the allele frequencies were 22.8% (95% CI: 19.3–26.3) and 15.8% (13.1–18.5) among Type 2 diabetic patients and non-diabetic subjects respectively. Assuming a significance level of 0.05 our study has a power of 99.7% for detecting a difference of the same magnitude as that reported in the British study, and a power of 65% to detect a relative diabetes risk of 1.2. Thus, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that the K variant of BCHE has a diabetogenic impact. Differences in ethnicity and known glucose tolerance status of the control subjects may account for some of the discrepancy observed. However, the failure to replicate the original finding may be primarily attributable to differences in sample sizes, as larger studies often give a more conservative estimate of the genetic effect [23]. The observation that small studies may yield more favourable outcomes than larger studies suggests either genuine heterogeneity or a bias against publication of small studies with negative results [23]. This underscores the need for large, well-characterised samples in investigations of Type 2 diabetes and other genetically complex diseases.

To show subtle effects of the K variant on pancreatic beta cell function, we measured serum insulin and C-peptide release after an oral glucose load in the population-based samples of normal glucose-tolerant subjects. No consistent impact of the gene variant could be demonstrated.

In conclusion, our study showed no association between the BCHE codon 539 Thr-allele and Type 2 diabetes. It was not possible to replicate the initial finding of a higher BMI in homozygous carriers of the BCHE polymorphism in 4424 glucose-tolerant subjects, and no association with other pre-diabetic phenotypes was demonstrated.

Abbreviations

- BCHE:

-

butyrylcholinesterase

- IAPP:

-

islet amyloid polypeptide

- MAF:

-

minor allele frequency

- NGT:

-

normal glucose-tolerant

- OHA:

-

oral hypoglycaemic agent

References

Jaikaran ETAS, Clark A (2001) Islet amyloid and Type 2 diabetes: from molecular misfolding to islet pathophysiology. Biochim Biophys Acta 1537:179–203

Pildal J, Lajer M, Hansen SK et al. (2003) Studies of variability in the islet amyloid polypeptide gene in relation to Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 20:491–494

Tilley L, Morgan K, Kalsheker N (1998) Genetic risk factors in Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Pathol 51:293–304

Mesulam MM, Geula C (1994) Butyrylcholinesterase reactivity differentiates the amyloid plaques of aging from those of dementia. Ann Neurol 36:722–727

Darvesh S, Graham DL, Hopkins DA (1998) Distribution of butyrylcholinesterase in the human amygdala and hippocampal formation. J Comp Neurol 393:374–390

Sáez-Valero J, Fodero LR, Sjögren M et al. (2003) Glycosylation of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase changes as a function of the duration of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Res 72:520–526

Ghebremedhin E, Thal DR, Schultz C, Braak H (2002) Age-dependent association between butyrylcholinesterase K-variant and Alzheimer disease-related neuropathology in human brains. Neurosci Lett 320:25–28

Bartels CF, Jensen FS, Lockridge O et al. (1992) DNA mutation associated with the human butyrylcholinesterase K-variant and its linkage the atypical variant mutation and other polymorphic sites. Am J Hum Genet 50:1086–1103

Yen T, Nightingale BN, Burns JC, Sullivan DR, Stewart PM (2003) Butyrylcholinesterase (BCHE) genotyping for post-succinylcholine apnea in an Australian population. Clin Chem 49:1297–1308

Minor DL, Kim PS (1994) Measurement of the β-sheet-forming propensities of amino acids. Nature 367:660–663

Pepys MB, Hawkins PN, Booth DR et al. (1993) Human lysozyme gene mutations cause hereditary systemic amyloidosis. Nature 362:553–557

Wiebusch H, Poirier J, Sevigny P, Schappert K (1999) Further evidence for a synergistic association between APOE ε4 and BCHE-K in confirmed Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Genet 104:158–163

McIlroy SP, Crawford VL, Dynan KB et al. (2000) Butyrylcholinesterase K variant is genetically associated with late onset Alzheimer’s disease in Northern Ireland. J Med Genet 37:182–185

Lehmann DJ, Williams J, Mcbroom J, Smith AD (2001) Using meta-analysis to explain the diversity of results in genetic studies of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease and to identify high-risk subgroups. Neuroscience 108:541–554

Vionnet N, Hani EH, Dupont S et al. (2000) Genomewide search for Type 2 diabetes susceptibility genes in French Whites: evidence for a novel susceptibility locus for early-onset diabetes on chromosome 3q27-qter and independent replication of a Type 2 diabetes locus on chromosome 1q21-q24. Am J Hum Genet 67:1470–1480

Drivsholm T, Ibsen H, Schroll M, Davidsen M, Borch-Johnsen K (2001) Increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance among 60-year-old Danes. Diabet Med 18:126–132

Glümer C, Jørgensen T, Borch-Johnsen K (2003) Prevalences of diabetes and impaired glucose regulation in a Danish population: the Inter99 study. Diabetes Care 26:2335–2340

WHO Study Group (1999) Report of a WHO consultation: part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. World Health Organization, Geneva

Ek J, Andersen G, Urhammer SA et al. (2001) Mutation analysis of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1 (PGC-1) and relationships of identified amino acid polymorphisms to Type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 44:2220–2226

Buetow KH, Edmonson M, MacDonald R et al. (2001) High-throughput development and characterization of a genomewide collection of gene-based single nucleotide polymorphism markers by chip-based matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:581–584

Hashim Y, Sheperd D, Wiltshire S et al. (2001) Butyrylcholinesterase K variant on chromosome 3 q is associated with Type II diabetes in white Caucasian subjects. Diabetologia 44:2227–2230

Hashim Y, Sheperd D, Wiltshire S et al. (2002) Butyrylcholinesterase K variant on chromosome 3 q is associated with Type II diabetes in white Caucasian subjects. Diabetologia 45:459 (Errata)

Ioannidis JPA, Trikalinos TA, Ntzani EE et al. (2003) Genetic associations in large versus small studies: an empirical assessment. Lancet 361:567–571

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Danish Medical Research Council, the Danish Diabetes Association, the Danish Heart Foundation, the Velux Foundation, and the EEC (BMH4-CT98-3084 and QLRT-CT-1999-00 546). Professor H. B. Mortensen, MD, is thanked for valuable supervision of A. Johansen’s PhD project. We also thank Birger Thorsteinsson, DMSc, MD, for the collection of some of the patients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Johansen, A., Nielsen, EM.D., Andersen, G. et al. Large-scale studies of the functional K variant of the butyrylcholinesterase gene in relation to Type 2 diabetes and insulin secretion. Diabetologia 47, 1437–1441 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-004-1459-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-004-1459-7