Abstract

Objective

Mobile head computed tomography (CT) scanners can reduce transport-related complications in neurointensive care unit (NICU) patients and decrease the burden on NICU staff; however, the initial investment cost and reduced image quality of early mobile scanners have prevented their widespread clinical use. Here, we report our initial experience with a novel 32-row mobile CT scanner for use in NICUs.

Methods

Over a 2-year period, 107 patients received a mobile head CT scan. The technical characteristics of the scanner and the organizational procedures are described in detail. Patient characteristics were retrospectively collected and image quality was subjectively evaluated on a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 5 and compared with a stationary CT scanner.

Results

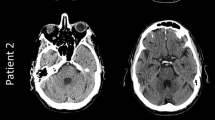

Mobile head CT was used for follow-up of intracranial hemorrhage in 51%, routine postoperative imaging in 28%, evaluation of neurological deterioration in 14%, bedside monitoring after external ventricular drain placement in 4%, and follow-up of ischemic stroke in 3% of cases. Diagnostic imaging quality was achieved in all cases, eliminating the need for stationary CT scanning. The overall image quality of mobile CT (median 4 points) was inferior to that of conventional stationary CT (median 5 points, p < 0.01), but was rated with 4 or 5 points in the majority of cases.

Conclusions

State-of-the-art mobile CT was found to be easy to use and maneuver and has the potential to expedite the diagnosis of NICU patients and reduce staff workload. Image quality was adequate for common NICU issues.

Zusammenfassung

Ziel

Durch mobile Kopf-Computertomographie(CT)-Scanner können transportbedingte Komplikationen bei Patienten auf neurologischen Intensivstationen (NICU) und die Belastung des Personals dort vermindert werden, jedoch haben die anfänglichen Investitionskosten und eine verminderte Bildqualität der frühen mobilen Scanner ihre Verbreitung im klinischen Einsatz verhindert. In der vorliegenden Arbeit berichten die Autoren über ihre ersten Erfahrungen mit einem neuartigen mobilen 32-Zeilen-CT-Scanner für den Einsatz auf NICU.

Methoden

In einem Zeitraum von 2 Jahren wurde bei 107 Patienten eine mobile Kopf-CT-Untersuchung durchgeführt. Technische Merkmale des Geräts und organisatorische Abläufe werden detailliert beschrieben. Die Patientenmerkmale wurden retrospektiv erhoben und die Bildqualität subjektiv auf einer Likert-Skala von 0 bis 5 bewertet und mit einem stationären CT-Scanner verglichen.

Ergebnisse

Die mobile Kopf-CT kam für Nachuntersuchungen bei intrakranialer Blutung in 51%, für postoperative Routinebildgebung in 28%, zur Beurteilung einer neurologischen Verschlechterung in 14%, zum Bedside-Monitoring nach externer Ventrikeldrainagenplatzierung in 4% und für Nachuntersuchungen bei ischämischem Schlaganfall in 3% der Fälle zum Einsatz. Dabei wurde in allen Fällen eine zu diagnostischen Zwecken ausreichende Bildqualität erzielt, wodurch keine Notwendigkeit einer Untersuchung mittels stationärem CT-Gerät mehr bestand. Die Bildqualität des mobilen CT-Geräts (Median: 4 Punkte) war insgesamt schlechter als die des herkömmlichen stationären CT-Geräts (Median: 5 Punkte; p < 0,01), allerdings in der Mehrzahl der Fälle mit 4 oder 5 Punkten bewertet worden.

Schlussfolgerung

Das mobile CT-Gerät auf dem neuesten Stand wurde als einfach zu bedienen und zu bewegen empfunden und hat das Potenzial, die Diagnosestellung bei NICU-Patienten zu beschleunigen sowie die Belastung des Personals zu reduzieren. Für die üblichen NICU-Fragestellungen war die Bildqualität ausreichend.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability statement

The data will be made available upon reasonable request.

References

Torbey MT (2019) Neurocritical care. Cambridge University Press

Williamson C, Morgan L, Klein JP (2017) Imaging in neurocritical care practice. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. Thieme, pp 840–852

Gunnarsson T, Theodorsson A, Karlsson P, Fridriksson S, Boström S, Persliden J et al (2000) Mobile computerized tomography scanning in the neurosurgery intensive care unit: increase in patient safety and reduction of staff workload. JNS 93:432–436

Smith I, Fleming S, Cernaianu A (1990) Mishaps during transport from the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 18:278–281

Abdullah AC, Adnan JS, Rahman NAA, Palur R (2017) Limited evaluation of image quality produced by a portable head CT scanner (CereTom) in a neurosurgery centre. Malaysian J Med Sci Mjms 24:104

McCollough CH, Bruesewitz MR, McNitt-Gray MF, Bush K, Ruckdeschel T, Payne JT et al (2004) The phantom portion of the American College of Radiology (ACR) computed tomography (CT) accreditation program: practical tips, artifact examples, and pitfalls to avoid. Med Phys 31:2423–2442

Durward QJ, Amacher AL, Del Maestro RF, Sibbald WJ (1983) Cerebral and cardiovascular responses to changes in head elevation in patients with intracranial hypertension. JNS 59:938–944

Chesnut RM, Temkin N, Carney N, Dikmen S, Rondina C, Videtta W et al (2012) A trial of intracranial-pressure monitoring in traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med 367:2471–2481

Smith M (2008) Monitoring intracranial pressure in traumatic brain injury. Anesth Analg 106:240–248

Chesnut RM, Bleck TP, Citerio G, Classen J, Cooper DJ, Coplin WM et al (2015) A consensus-based interpretation of the benchmark evidence from South American trials: treatment of intracranial pressure trial. J Neurotrauma 32:1722–1724

Miller JD, Becker DP, Ward JD, Sullivan HG, Adams WE, Rosner MJ (1977) Significance of intracranial hypertension in severe head injury. JNS 47:503–516

Teichgräber UK, Pinkernelle J, Jürgensen J‑S, Ricke J, Kaisers U (2003) Portable computed tomography performed on the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med 29:491–495

Butler WE, Piaggio CM, Constantinou C, Niklason L, Gonzalez RG, Cosgrove GR et al (1998) A mobile computed tomographic scanner with intraoperative and intensive care unit applications. Neurosurgery 42:1304–1310

Matson MB, Jarosz J, Gallacher D, Malcolm P, Holemans J, Leong C et al (1999) Evaluation of head examinations produced with a mobile CT unit. Br J Radiol 72:631–636

Carlson AP, Yonas H (2012) Portable head computed tomography scanner-technology and applications: experience with 3421 scans. J Neuroimaging 22:408–415

Masaryk T, Kolonick R, Painter T, Weinreb DB (2008) The economic and clinical benefits of portable head/neck CT imaging in the intensive care unit. Radiol Manag 30:50–54

Rumboldt Z, Huda W, All J (2009) Review of portable CT with assessment of a dedicated head CT scanner. Am J Neuroradiol 30:1630–1636

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

C. Kabbasch serves as consultant for Acandis GmbH (Pforzheim, Germany) and as proctor for MicroVention Inc./Sequent Medical (Aliso Viejo, CA, USA). D. Zopfs is on the speaker’s bureau of Philips (Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and lecturer for Amboss GmbH (Cologne, Germany). L. Goertz, Y. Al-Sewaidi, M. Habib, B. Reichardt and A. Ranft declare that they have no competing interests.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants or on human tissue were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1975 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was conducted in accordance with the STROBE guidelines in compliance with the national legislation and the Code of Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

The supplement containing this article is not sponsored by industry.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors Alexander Ranft and Christoph Kabbasch contributed equally to the manuscript as last authors.

Scan QR code & read article online

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goertz, L., Al-Sewaidi, Y., Habib, M. et al. Initial experience with a state-of-the-art mobile head CT scanner for use in neurointensive care units. Radiologie (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00117-024-01304-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00117-024-01304-1