Abstract

Evidence of the impact of climate change on health is growing. Health systems need to be prepared and gradually adapt to the effects of climate change, including extreme weather events.

Fossil fuel combustion as the driver of climate change poses a tremendous burden of disease. In turn, cutting greenhouse gas emissions in all sectors will achieve health co-benefits. If all countries meet the Paris Agreement by 2030, the annual number of avoidable premature deaths could total 138,000 across the entire European Region of the World Health Organization (WHO).

Several international frameworks promote a stronger commitment by countries to implementing the necessary adaptations in the health sector and to addressing health considerations in adaptation measures in other sectors. The WHO has a mandate from its member states to identify solutions and help prevent or reduce health impacts, including those from climate change.

National governments are continuing to establish public health adaptation measures, which provide a rationale for and trigger action on climate change by the health community. Effective national responses to climate risks require strategic analyses of current and anticipated threats. Health professionals need to play a proactive role in promoting health arguments and evidence in the formulation of national climate change adaptation and mitigation responses. To this end, country capacities need to be further strengthened to identify and address local health risks posed by climate change and to develop, implement and evaluate health-focused interventions through integrated approaches. Building climate-resilient and environmentally sustainable health care facilities is an essential pillar of health sector leadership to address climate change.

Zusammenfassung

Es gibt immer mehr Erkenntnisse zu den Auswirkungen des Klimawandels auf die Gesundheit. Die Gesundheitssysteme müssen darauf vorbereitet werden und sich schrittweise an die Auswirkungen des Klimawandels einschließlich extremer Wetterereignisse anpassen. Von der Verbrennung fossiler Brennstoffe als treibender Faktor des Klimawandels geht eine große Krankheitslast aus. Umgekehrt wird die Senkung der Treibhausgasemissionen in allen Sektoren auch mit positiven Nebeneffekten für die Gesundheit einhergehen. Wenn alle Länder bis 2030 das Pariser Übereinkommen erfüllen, könnte sich die jährliche Zahl der vermeidbaren vorzeitigen Todesfälle in der gesamten europäischen Region der Weltgesundheitsorganisation (WHO) auf 138.000 belaufen. Mehrere internationale Rahmenbedingungen fördern ein stärkeres Engagement der Länder für die Umsetzung notwendiger Anpassungen im Gesundheitssektor und für die Berücksichtigung gesundheitspolitischer Aspekte bei Anpassungsmaßnahmen anderer Sektoren. Die WHO hat von ihren Mitgliedstaaten den Auftrag, Lösungen zu benennen und zur Vermeidung oder Verringerung negativer gesundheitlicher Auswirkungen, auch durch den Klimawandel, beizutragen. Die nationalen Regierungen führen weiterhin Anpassungen im Bereich der öffentlichen Gesundheit ein, die eine Begründung für Maßnahmen der Gesundheitsgemeinschaft gegen den Klimawandel bieten und solche Maßnahmen auslösen. Wirksame innerstaatliche Reaktionen auf Klimarisiken erfordern strategische Analysen aktueller und erwarteter Bedrohungen. Die Angehörigen der Gesundheitsberufe müssen eine proaktive Rolle spielen, indem sie die stärkere Berücksichtigung gesundheitlicher Argumente und Erkenntnisse bei der Formulierung innerstaatlicher Maßnahmen zur Anpassung an den Klimawandel und zum Klimaschutz fördern. Hierzu müssen die Kapazitäten der Länder weiter ausgebaut werden, damit von Klimaänderungen ausgehende lokale Gesundheitsrisiken identifiziert werden können, damit diesen entgegengewirkt werden kann und damit durch integrierte Ansätze gesundheitsförderliche Maßnahmen entwickelt, durchgeführt und bewertet werden können. Der Aufbau klimaresistenter und ökologisch nachhaltiger Gesundheitseinrichtungen ist eine wesentliche Säule der Führungsrolle des Gesundheitssektors bei der Bekämpfung des Klimawandels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Some of the climatic change in recent years has established new record levels, such as for global and European temperatures, winter Arctic sea ice extent and sea levels [1]. Climate change is already affecting human health, with increasing exposures and vulnerability recorded worldwide [2].

Key reports of global and European relevance include the series of government-approved reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), specifically the special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C [2] and its fifth assessment report, which reviewed the evidence on climate change and health and provided summaries for policy-makers [3, 4]. The health synthesis report aims to summarize the findings of the IPCC special 1.5 report regarding the relationship between climate change and health [5]. In 2015, the Lancet Commission published the report on climate change and global environmental change [6]. In 2017, the WHO Regional Office for Europe presented an update on protecting health in Europe from climate change, drawing on the extensive body of new research and evidence [7].

Health impacts of climate change and variability are being observed: direct impacts result through temperature increases, heat waves, storms, forest fires, floods and droughts. Indirect impacts are mediated through the effects of climate change on biodiversity, vectors distribution, allergens, ecosystems and productive sectors, such as agriculture, water and food supplies.

Climate change will affect everybody, but vulnerability to weather and climate change depends on people’s level of exposure, their personal characteristics (such as age, education, income and health status) and their access to health services. Elderly people, children, outdoor workers and homeless people are particularly susceptible population groups [8, 9]. The effects of exposure can be direct or indirect, for example heat spells may directly cause heat stress, dehydration or heat stroke, while the worsening of cardiovascular and respiratory conditions or electrolyte disorders may be indirect consequences [10, 11]. Climate change affects environmental conditions and social infrastructure, which also determine the health effects, ranging from death to loss of well-being and productivity.

The pathways by which climate change can affect health have been explained in a number of conceptual frameworks [6, 12]. Fig. 1 presents a combination and adaptation of these frameworks relevant to the WHO European Region [7].

Pathways of climate change and health (adapted from WHO Regional Office for Europe [7])

The WHO Regional Office for Europe works with the Member States to generate evidence, develop supporting tools and to identify best policy options to minimize the health effects of climate change. The aim of this article is to support the communication and implementation of existing global and regional commitments and priorities to protect health from the adverse effects of climate change.

Climate change is a matter of public health

Climate change is influencing mortality, injury and morbidity rates of both communicable (such as vector- and waterborne diseases) and non-communicable (such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases as well as mental health issues) diseases [6, 7, 9].

The increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events due to climate change pose growing risks to human health. Heat-waves were the deadliest extreme climate event in Europe between 1991 and 2015, particularly in southern and western Europe. Several extreme heat-waves have occurred since 2000 (in 2003, 2006, 2007, 2010, 2014, 2015 and 2016) [1]. Exceptionally persistent and high July temperatures in 2018 baked countries across the WHO European Region, including northern Europe and even above the Arctic circle in Lapland, setting the stage for catastrophic forest fires in Greece, for example [13]. Sweden experienced a large number of wildfires due to a prolonged heatwave in summer 2018, which the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency considered the most serious in the modern history of the country [14]. In the summer of 2017, Portugal was severely affected by wildfires, which occurred during a concurrent heatwave and severe drought, killing 65 people [15]. In Greece, Italy and France, severe alert warning messages were also issued in 2017, indicating that even healthy and active people could suffer from possible negative effects. In Italy, hospital admissions went up by 15% during the heatwave [16]. The heatwave during the summer of 2003 claimed more than 70,000 lives across mostly western European countries [17], and in 2010 many eastern European cities recorded extremely high temperatures, particularly in the Russian Federation, where the deaths attributable to these high temperatures were estimated at around 55,000 [18]. Urban populations are at risk of multiple exposures; for example air pollution also increases the health risks associated with high temperatures [11].

High air temperatures can adversely affect food quality during transport, storage and handling. Elevated marine water temperatures accelerate the growth rate of certain pathogens, such as Vibrio species that can cause foodborne outbreaks after eating seafood and wound infections in injured skin exposed to contaminated marine water [1].

Cold spells were the deadliest weather extremes in eastern Europe, with cumulative numbers of deaths of 28 per 1,000,000 people over the whole time period (1991–2015) [1]. Prolonged cold spells affect physiological and pathological health, especially among elderly people and those with respiratory and cardiovascular diseases [19].

By the end of the 21st century, two thirds of Europeans could be exposed to weather-related disasters every year, compared with only 5% during the period 1981–2010. Climate change is the dominant driver of the projected trends, accounting for more than 90% of the rise in the risk to humans [20]. Flood events registered since 1991 have caused the death of more than 2000 people in the WHO European Region, affected 8.7 million others and generated at least 72 billion Euro in losses [21]. Two thirds of deaths associated with flooding occur from drowning; the rest result from physical trauma, heart attacks, electrocution, carbon monoxide poisoning or fire associated with flooding. Infectious disease vectors such as mosquitoes and rodents may also increase as a result of flooding [1].

Climate change is likely to cause changes in ecological systems that will affect the risk of infectious diseases in the WHO European Region through water, food, air, rodents and arthropod vectors [7, 22]. Waterborne pathogens may be transmitted through two major exposure pathways: drinking water (if water treatment and disinfection are inappropriate) and recreational water use. Heavy precipitation and flooding events can disrupt water treatment and distribution infrastructures, increasing the risk of ingress of faecal pathogens and thus of waterborne outbreaks [21, 22].

Climate risks associated with increases in drought frequency and magnitude include impacts on quality and quantity of freshwater resources, including eutrophication and algae blooms, with possible impacts on drinking-water quality. Droughts may also compromise food safety and security and cause mental health effects, vector-borne diseases and injuries due to lower than usual water levels in lakes and rivers that are used for recreation [23]. Many parts of the Mediterranean region experienced significant drought in 2017, including Italy with the most severe anomalies in annual rainfall 26% below the 1961–1990 average [24]. Water scarcity is accelerating across the European Region and can pose additional challenges for providing sustainable water and sanitation services. The occurrence of waterborne diseases is related to water quality and may be affected by changes in runoff, seasonality and frequency of extreme events such as heavy rains, floods and droughts [12]. Areas under high water stress, for example, are estimated to increase from 19% in 2007 to 35% by the 2070s, by which time the number of additional people affected is expected to reach 16 million to 44 million [7].

Global and regional policy frameworks for climate action and health

An important aspect of tackling challenges around health and climate change is establishing mechanisms to monitor health impacts and setting targets to reduce these. Several international policy frameworks and platforms are in place (Table 1); these stipulate a clear mandate to foster stronger engagement of the health sector with climate change adaptation and mitigation.

Since 1999, with the adoption of the Declaration of the Third Ministerial Conference on Environment and Health held in London, United Kingdom [33], Member States of the WHO European Region have been committed to action towards mitigation of and adaptation to climate change.

Health in climate change adaptation

Coherent multisectoral action is necessary to effectively tackle the challenges posed by climate change. Health considerations are increasingly on the agendas of sectors and actors addressing climate change. In turn, a consideration of climate change warrants a correspondingly prominent place on the health agenda. The effects of climate change may threaten the overall progress made in reducing the burden of diseases and injuries by increasing morbidity and mortality. Evidence suggests that there is a very high benefit–cost ratio for health adaptation, and that higher benefits are achieved with early adaptation action [34].

Under the UNFCCC process, the Paris Agreement on Climate Change is the first universal, legally binding global deal to combat climate change and adapt to its effects [25]. Its global goal on adaptation focuses on “enhancing adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience and reducing vulnerability to climate change, with a view to contributing to sustainable development and ensuring an adequate adaptation response in the context of the global temperature goal”. With regard to health, implementation of the Paris Agreement provides its parties with opportunities to strengthen the climate resilience of their health systems—for example, through improved disease surveillance and preparedness for extreme weather events and ensuring climate-resilient health facilities, with undisturbed access of health facilities to essential services such as energy, water and sanitation.

With regard to the Paris Agreement, only 18% of all 53 WHO European Member States refer to health in their “intended nationally determined contributions” (INDCs) when outlining commitments to achieving climate-related policy goals and targets, compared with 67% of countries globally [35].

To promote and position health as a key driver for climate actions, the health community needs to play an active role in awareness-raising and advocacy, and in strengthening the evidence base on the health impacts of climate change. This also includes integrating climate resilience into existing and future core health system programming and developing tools to assess the health implications of mitigation policies [36].

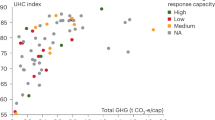

The WHO carried out targeted surveys in 2012 and 2017 among its Member States (i. e. with 22 countries participating in 2012 and 20 countries in 2017) to track the status and progress of how health is positioned in existing climate change policies and programming in the European Region [37, 38]. The surveys primarily focused on governance of climate change and health, the status of health vulnerability and impact assessments, the existence of national adaptation health policies, the strengthening of health systems and the raising of awareness. The findings are summarized in Fig. 2.

Governance mechanisms on climate change and health improved between 2012 and 2017. In 2012, already 96% of responding countries had established a multisectoral committee on climate change whose primary role is to coordinate actions and policies for both adaptation and mitigation, including relevant health aspects. In 2017, all responding countries confirmed the existence of such a governmental body.

Similar progress could be observed in implementing health vulnerability and impact assessments. These assessments are a key instrument to provide information for decision-makers on the extent and magnitude of likely health risks attributable to climate change and to identify and prepare for changing health risks. They can suggest priority policies and programmes that can prevent or reduce the severity of future climate change health impacts. WHO developed a guideline that is designed to provide the basics on conducting a national or sub-national health vulnerability and impact assessments [39]. In 2012, 77% of the 22 responding countries stated that they had conducted health-specific assessments of the impacts, vulnerability and adaptation to climate change. In 2017, the percentage of countries performing such assessments had increased to 85% of the 20 responding countries.

Adaptation is defined by the IPCC as “the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects. In human systems, adaptation seeks to moderate harm or exploit beneficial opportunities. In natural systems, human interventions may facilitate adjustment to expected climate and its effects” [12]. As climate change is one of the many factors associated with the incidence of numerous adverse health outcomes, there is a need to design policies, plans and measures that address the health risks of climate change in order to prevent and reduce the severity of current and future impacts. The development of adaptation plans and programmes for the health sector will depend on and vary according to the specific needs identified during vulnerability impact assessments [40, 41]. In 2012, national health adaptation plans or strategies on climate change had been developed in 64% of the 22 responding countries, with nine countries (40%) reporting that these policies were approved by the government. In 2017, 15 of the responding countries had developed a climate change health adaptation strategy and an associated implementation plan (75%), and these were approved by the government in 13 countries (65%).

In 2012, 83% of responding countries reported that they had taken actions towards strengthening public health capacities and health systems to cope with impacts of climate change; at 85% in 2017, this figure remained almost unchanged. The examples of measures taken by Member States to improve health systems included strengthened early-warning systems and responses, infectious disease surveillance, as well as improved water and sanitation services.

In 2012, 75% of responding Member States reported a high level of awareness of the relevance of health effects on climate change and a sizeable influence in political developments as compared with 65% in 2017. Examples on well-developed health communications regarding extreme weather events showed that climate change and health are perceived as an important topic in political developments [37, 38].

The need to minimize and prevent adverse climate change-related health outcomes highlights the need for inclusion of health as a consideration in all policies, across all sectors. The 2030 Agenda specifically addresses health (Sustainable Development Goal/SDG 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages) and climate change (SDG 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts), as well as a range of targets that support action to protect and promote health through increasing adaptive capacity and health resilience to climate risks, prioritizing mitigation actions that benefit health and pushing the health sector to become less carbon-intensive and more environment-friendly [26]. While responding to climate change is a cross-government priority in many countries, it requires the health sector to work both internally and in a coordinated manner with other actors, often under a single climate change strategy and coordinating mechanism, to define adequate measures. Implementation of the UNFCCC is strongly supported by the 2030 Agenda, which explicitly acknowledges that the UNFCCC “is the primary international, intergovernmental forum for negotiating the global response to climate change”.

The health sector therefore needs to lead adaptation planning for health, working with other sectors to achieve health benefits.

Health in climate change mitigation

Both air pollutants and greenhouse gases (GHG) are emitted from many of the same sectors, including energy, transport, housing and agriculture. The short-lived climate pollutants such as black carbon, methane and ozone have important impacts on both climate and health. Fossil fuel combustion as the driver of climate change poses a large burden of disease, including a major contribution to the 7 million deaths from outdoor and indoor air pollution annually [7].

The Paris Agreement on Climate Change identifies and promotes measures that both mitigate climate change and improve health, for example, by reducing carbon emissions, air pollution and the environmental impact of the health sector itself [25].

Countries in the WHO European Region have made very substantial commitments to reducing their GHG emissions. The combined commitment of the 53 Member States is equivalent to reducing overall GHG emissions in the region by 26% by 2030, estimated in comparison with baseline emissions in 1990 [41]. Most have set targets to reduce carbon emissions below 1990 levels, while others have set emission caps or intend to reduce future emission growth rates relative to a “business as usual” scenario. Further reductions could be achieved through international cooperation, knowledge sharing and financial support.

Most measures and policies to reduce GHG emissions can benefit human health, if adequately designed and implemented. Carbon-cutting policies that are known to provide health benefits include those that reduce emissions of health-damaging pollutants through changes in energy production, energy efficiency, sustainable transportation and control of landfills, among others.

These commitments are reflected in Member States’ official submissions to the Secretariat of UNFCCC as INDCs, which reflect countries’ ambition to reduce emissions, given their capabilities and circumstances. The annual preventable premature mortality could amount to 138,000 deaths across the whole WHO European Region, of which 33% (45,350 deaths) would be averted across 28 countries of the European Union in 2030 and beyond. In economic terms, the benefit of reduced emissions is equivalent to a savings of 244–564 billion US dollars, or 1%–2% of the WHO European Region gross domestic product (at purchasing power parity prices). The saved costs of illnesses (34.3 billion US dollars) amount to between 6% and 14% of the total economic benefit [41].

Conclusions

The protection of health from the effects of climate change has developed from a niche topic to high-level policy attention, as reflected in international agreements such as the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Increasingly, the call to integrate health into all policies and the need to consider climate change in all policies are being recognized and implemented. Understanding and awareness of health risks from climate change is growing fast within the health community; this needs to be reflected as core elements in training and career development for health professionals. Capacity-building is supported through the setting of norms and standards, the development of technical guidance and training courses and the mainstreaming of climate change and health topics into medical and public health training.

The health sector can support and inform policy-making towards the full potential of healthy mitigation through intersectoral action, advocacy, health impact assessment, identifying health co-benefits and win–win policy options and leading by example in reducing its own carbon emissions.

WHO aspires, among others, to support national, regional and global advocacy, provide evidence through country profiles and business cases for investment, ensure technical and capacity-building support for implementation and support climate-resilience, energy and water access in health care facilities. The WHO thirteenth general programme of work (GPW13) is woven around three strategic priorities, each setting a goal of 1 billion people and collectively known as the “triple billion” goal. These include: 1 billion more people benefiting from universal health coverage, 1 billion more people better protected from health emergencies and 1 billion more people enjoying better health and well-being. GPW13 highlights the importance of addressing climate change and health, specifically in small island developing states and other vulnerable settings, and of strengthening cross-sectoral collaboration towards health in all policies. To this end, WHO aims “to ensure that health systems become resilient to extreme weather and climate-sensitive disease” and “to help countries to ensure that global carbon emissions are falling so as to bring health ‘co-benefits’” by 2030 [32].

The draft WHO global strategy on health, environment and climate change, which is to be considered by the Seventy-second World Health Assembly in May 2019, aims to support GPW13 in providing a vision and way forward on how the world and its health community can respond to environmental health and climate change risks and challenges up to 2030 [42]. In the WHO European Region for the priority area of climate change and health, the Ostrava Declaration on Environment and Health calls upon “countries to strengthen adaptive capacity and resilience to climate change-related health risks, to support measures to mitigate climate change and to achieve health co-benefits in line with the Paris Agreement”. To achieve these objectives and planned ones in the forthcoming strategy, countries can include in their national portfolios some proposed actions listed in Table 2.

The health community should be fully engaged in the national intersectoral mechanisms for adaptation to climate change, including contributing to the development of the health components of national adaptation plans, of nationally determined contributions to the UNFCCC and of the national SDG implementation plans.

Vladimir Kendrovski and Oliver Schmoll are staff members of the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decision or stated policy of the World Health Organization.

References

European Environment Agency (2017) Climate change, impacts and vulnerability in Europe 2016. http://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/climate-change-impacts-and-vulnerability-2016. Accessed 11 Oct 2018

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2018) Global warming of 1.5°C. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2018/07/SR15_SPM_version_stand_alone_LR.pdf. Accessed 26 Feb 2019 (An IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas mission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty)

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2014) Summary for policymakers. In: Core Writing Team, Pachauri RK, Meyer LA (eds.) Climate change 2014: Synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva: IPCC. http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/. Accessed 11 Nov 2018

Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner GK, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J et al (eds) (2013) Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/. Accessed 11 Nov 2018

Ebi K, Campbell-Lendrum D, Wyns A (2018) The 1.5 health report: Synthesis on health & climate science in the IPCC Sr1.5. http://www.who.int/globalchange/181008_the_1_5_healthreport.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 26 Feb 2019

Watts N, Adger WN, Agnolucci P, Blackstock J, Byass P, Cai W et al (2015) Health and climate change: Policy responses to protect public health. Lancet 386(10006):1861–1914. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60854-6 (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673615608546, accessed 11.10.2018)

WHO Regional Office for Europe (2017) Protecting health in Europe from climate change: 2017 update. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/355792/ProtectingHealthEuropeFromClimateChange.pdf?ua=1,accessed. Accessed 26 Feb 2019 (http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/Climate-change/publications/2017/protecting-health-in-europe-from-climate-change-2017-update)

Paavola J (2017) Health impacts of climate change and health and social inequalities in the UK. Environ Health 16(Suppl 1):113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0328-z

Wolf T, Lyne K, Martinez GS, Kendrovski V (2015) The health effects of climate change in the WHO European region. Climate 3:901–936

Åström DO, Forsberg B, Edvinsson S, Rocklöv J (2013) Acute fatal effects of short-lasting extreme temperatures in Stockholm, Sweden: Evidence across a century of change. Epidemiology 24(6):820–829. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ede.0000434530.62353.0b

Analitis A, Michelozzi P, D’Ippoliti D, De’Donato F, Menne B, Matthies F et al (2014) Effects of heat waves on mortality: Effect modification and confounding by air pollutants. Epidemiology 25(1):15–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/ede.0b013e31828ac01b

Smith KR, Woodward A, Campbell-Lendrum D, Chadee DD, Honda Y, Liu Q et al (2014) Human health: Impacts, adaptation, and co-benefits. http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg2/. Accessed 11 Nov 2018 (In: Field CB, Barros VR, Dokken DJ, Mach KJ, Mastrandrea MD, Bilir TE et al. (eds). Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Lancet Editorial (2018 Heatwaves and Health. Lancet. 392(10145):359. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30434-3

MSB Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (2018) Announcement to the general public the 23rd of July. https://www.msb.se/en/Tools/News/Announcement-to-the-general-public-23-July/. Accessed 26 Feb 2019

Viegas DX (2017) O complexo de incêndios de Pedrógão Grande e concelhos limítrofes, iniciado a 17 de junho de 2017 [The complex of fires of Great Pedrógão and bordering counties, starting on 17 June 2017]. Coimbra: Centro de Estudos sobre Incêndios Florestais, Universidade de Coimbra

The Lancet Countdown: Tracking Progress on Health and Climate Change (2017) Lancet Countdown: EU policy briefing. http://www.lancetcountdown.org/resources/. Accessed 15 Oct 2018

Robine JM, Cheung SL, Le Roy S, Van Oyen H, Griffiths C, Michel JP et al (2008) Death toll exceeded 70 000 in Europe during the summer of 2003. C R Biol 331(2):171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crvi.2007.12.001

Barriopedro D, Fischer M, Luterbacher J, Trigo M, García-Herrara R (2011) The hot summer of 2010: Redrawing the temperature record map of Europe. Science 332:220–224. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1201224

Ryti N, Guo Y, Jaakkola J (2015) Global association of cold spells and adverse health effects: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Health Perspect 124(1):12–22. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1408104

Forzieri G, Cescatti A, Batista e Silva F, Feyen L (2017) Increasing risk over time of weather-related hazards to the European population: A data-driven prognostic study. Lancet Planet Health 1(5):e200–e208. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30082-7

WHO Regional Office for Europe (2017) Flooding: Managing health risks in the WHO European Region. http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/flooding-managing-health-risks-in-the-who-european-region-2017. Accessed 17 Oct 2018

Semenza JC, Lindgren E, Balkanyi L, Espinosa L, Almquist MS, Penttinen P et al (2016) Determinants and drivers of infectious disease threat events in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis 22(4):581–589. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2204.151073

Stanke C, Murray V, Amlôt R, Nurse J, Williams R (2012) The effects of flooding on mental health: Outcomes and recommendations from a review of the literature. PLoS Curr 1. https://doi.org/10.1371/4f9f1fa9c3cae

World Meteorological Organization (2018) WMO statement on the state of the global climate in 2017. https://library.wmo.int/doc_num.php?explnum_id=4453. Accessed 26 Feb 2019

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2015) The Paris Agreement. In: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. http://unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9485.php. Accessed 12 Nov 2018 (UFCCC/CP/2015/L.9:3)

United Nations (2015) Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E;. Accessed 12 Nov 2018

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR) (2015) Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. https://www.unisdr.org/we/coordinate/sendai-framework. Accessed 12 Oct 2018

WHO Regional Office for Europe (2017) Declaration of the Sixth Ministerial Conference on Environment and Health. http://www.euro.who.int/en/media-centre/events/events/2017/06/sixth-ministerial-conference-on-environment-and-health/documentation/declaration-of-the-sixth-ministerial-conference-on-environment-and-health. Accessed 12 Nov 2018

WHO Regional Office for Europe (2017) Annex 1: Compendium of possible actions to advance the implementation of the Ostrava Declaration. http://www.euro.who.int/en/media-centre/events/events/2017/06/sixth-ministerial-conference-on-environment-and-health/documentation/declaration-of-the-sixth-ministerial-conference-on-environment-and-health/annex-1.-compendium-of-possible-actions-to-advance-the-implementation-of-the-ostrava-declaration. Accessed 12 Nov 2018

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, WHO Regional Office for Europe (2006) Protocol on water and health to the 1992 convention on the protection and use of transboundary watercourses and international lakes. http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/policy-documents/protocol-on-water-and-health-to-the-1992-convention-on-the-protection-and-use-of-transboundary-watercourses-and-international-lakes. Accessed 12 Nov 2018

World Health Organization (2008) Resolution WHA61.19. Climate change and health. http://www.who.int/globalchange/health_policy/wha_eb_documentation/en/. Accessed 12 Oct 2018

World Health Organization (2018) Thirteenth general programme of work 2019–2023. http://www.who.int/about/what-we-do/gpw-thirteen-consultation/en/. Accessed 12 Oct 2018

WHO Regional Office for Europe (1999) Declaration. Third Ministerial Conference on Environment and Health. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/88585/E69046.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 26 Feb 2019

Hutton G, Menne B (2014) Economic evidence on the health impacts of climate change in Europe. Environ Health Insights 8:43–52. https://doi.org/10.4137/EHI.S16486

Menne B, Kendrovski V (2017) WHO: Health in climate-change negotiations. In: Kickbusch I, Kökény M (eds.). Health diplomacy: European perspectives. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/347688/Health_Diplomacy_European_Perspectives.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 26 Feb 2019

World Health Organization (2015) Operational framework for building climate resilient health systems. http://www.who.int/globalchange/publications/building-climate-resilient-health-systems/en/. Accessed 11 Oct 2018

Wolf T, Martinez GS, Cheong GH, Williams E, Menne B (2014) Protecting health from climate change in the WHO European region. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11(6):6265–6280. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110606265

WHO Regional Office for Europe (2018) Public health and climate change adaptation policies in the European Union: Final report. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/386965/Pagoda-REPORT-final-published-2.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 17 Dec 2018

World Health Organization (2013) Protecting health from climate change: Vulnerability and adaptation assessment. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/104200/9789241564687_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 26 Feb 2019

World Health Organization (2014) WHO guidance to protect health from climate change through health adaptation planning. Discussion draft. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/137383/9789241508001_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 26 Feb 2019

WHO Regional Office for Europe (2018) Achieving health benefits from carbon reductions: Manual for CaRBonH calculation tool. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/386923/health-carbon-reductions-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 11 Dec 2018

World Health Organization (2018) Draft WHO global strategy on health, environment and climate change. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/378903/68id07e_GlobalStrategyHealthEnvironmentClimateChange_180547.pdf. Accessed 11 Dec 2018

Acknowledgements

The work was conducted in the context of a joint WHO/EC project with funding from the European Commission under grant agreement: “Addressing the impacts of climate change on health” (34.0202/2016/741645/SUB/CLIMA.A3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

V. Kendrovski and O. Schmoll declare that they have no competing interests.

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies performed were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case.

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the WHO, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The use of the WHO’s name, and the use of the WHO’s logo, shall be subject to a separate written licence agreement between the WHO and the user and is not authorized as part of this CC-IGO licence. Note that the link provided above includes additional terms and conditions of the licence.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kendrovski, V., Schmoll, O. Priorities for protecting health from climate change in the WHO European Region: recent regional activities. Bundesgesundheitsbl 62, 537–545 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-019-02943-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-019-02943-9