Abstract

Purpose

To synthesise the evidence on the impact of pre-operative direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) on health outcomes for patients who sustain a hip fracture.

Method

A rapid systematic review of three databases (MEDLINE, Embase and Scopus) for English-language articles from January 2000 to August 2021 was conducted. Abstracts and full text were screened by two reviewers and articles were critically appraised. Data synthesis was undertaken to summarise health outcomes examined for DOAC users versus a no anticoagulant group. Key information was extracted for study type, country and time frame, population and sample size, type of DOACs, comparator population(s), key definitions, health outcome(s), and summary study findings.

Results

There were 21 articles identified. Of the 18 studies that examined time to surgery, 12 (57.1%) found DOAC users had a longer time to surgery than individuals not using anticoagulants. Five (83.3%) of six studies identified that DOAC users had a lower proportion of surgery conducted within 48 h Four (40.0%) of ten studies reporting hospital length of stay (LOS) identified a higher LOS for DOAC users. Where reported, DOAC users did not have increased mortality, blood loss, transfusion rates, complication rates of stroke, re-operation or readmissions compared to individuals not using anticoagulants.

Conclusions

The effect of DOAC use on hip fracture patient health was mixed, although patients on DOACs had a longer time to surgery. The review highlights the need for consistent measurement of health outcomes in patients with a hip fracture to determine the most appropriate management of patients with a hip fracture taking DOACs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sustaining a hip fracture is a serious injury for older adults aged ≥ 65 years, as the injury typically requires surgery, can result in ongoing mobility issues, reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL) or death [1,2,3,4]. Much of the evidence indicates that hip fracture surgery should be performed within 1 or 2 days after hospital admission to achieve the best health outcomes, and reduce hospital length of stay (LOS), the likelihood of complications, and mortality [5,6,7,8]. However, many older adults with a hip fracture have underlying chronic comorbid conditions, such as thromboembolic disease or atrial fibrillation, that are managed with antithrombotic medication [9]. Traditionally, the use of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) anticoagulants, such as warfarin, has necessitated reversal of their effects pre-operatively to reduce the patient’s international normalized ratio (INR) which may lead to delayed surgical intervention [10, 11].

Unlike VKAs, the use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), including factor Xa inhibitors (i.e., apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban) and a direct thrombin inhibitor (i.e., dabigatran), has the benefit of predictable pharmacokinetics without the need for regular monitoring [10]. However, the use of DOACs has resulted in acknowledged variations in practice in relation to health utilisation outcomes, such as time to surgery, after a hip fracture [10, 12]. While national clinical guidelines recommend hip fracture surgery within 48 hof hospital admission [13,14,15], there are few consistent guidelines around the pre-fracture use of DOACs and hip fracture surgery.

It is unclear whether the timing of surgical intervention for hip fracture patients prescribed DOACs adversely affects patient or health utilisation outcomes, such as blood loss or hospital LOS, respectively. Any delay to surgery needs to be balanced against potential increased risk of patient complications such as delirium, infection or thromboembolism. The HIP ATTACK study demonstrated that operating within 6 h of presentation with a hip fracture had no detrimental effect and was associated with a lower risk of delirium, urinary tract infection, and moderate to severe pain scores on days 4–7 compared to standard care [16]. Early surgery in HIP ATTACK led to faster mobilisation, a shorter hospital LOS and no difference in mortality compared to usual care [16].

Surgical delays to allow medical optimisation of patients taking pre-fracture anticoagulation treatment aim to reduce intra- and post-operative blood loss [17] and may be necessary to deliver safe regional anaesthesia [18]. As the use of DOACs is increasing among older adults [19], and with the number of hip fractures worldwide estimated to rise to 6.26 million by 2050 [20], whether there is evidence of a detrimental effect on health outcomes of older adults taking DOACs pre-operatively needs to be collated and synthesised. The aim of this systematic rapid review is to synthesise the current evidence on the impact of pre-operative DOACs on patient health outcomes for patients who sustain a hip fracture. This will inform future research, audit and guideline development.

Methods

This rapid systematic review synthesises the evidence on the impact of pre-operative DOACs on the health outcomes of older adults who underwent hip fracture surgery. The review records the type of DOACs examined, whether any comparator population(s) were included, the type of primary and secondary health outcomes examined, and summarises the findings of each study.

Definitions

Research articles were included in the rapid review if they examined health outcomes of patients who underwent hip fracture surgery. Articles were included if the population in the studies was primarily aged ≥ 60 years, was admitted to hospital after a hip fracture (e.g. intracapsular, trochanteric or subtrochanteric), and underwent surgery for the hip fracture (e.g. intramedullary nail or hip screw, hemiarthroplasty, total hip replacement).

The research articles included had to evaluate the impact of pre-operative DOACs (i.e., rivaroxaban, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban) on patient health outcomes. Comparator populations could include patients not taking DOACs, patients taking VKAs (e.g., warfarin) or patients taking oral platelet inhibitors (PAIs) (e.g., aspirin, clopidogrel, ticagrelor).

Patient health outcomes included those relating to health-care utilisation, such as time to surgery, mortality, hospital LOS, intensive care unit (ICU) LOS, blood loss, need for a blood transfusion, or post-operative complications (e.g., infection, bleeding, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis). For the purposes of this rapid review, measures of health outcomes related to life post-discharge, such as mental health, HRQoL, or ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), were excluded.

Data sources and eligibility criteria

A systematic search was conducted using three databases: MEDLINE, Embase, and Scopus. The search strategy was developed with a university librarian and included the following search terms: (anticoagulant* OR ‘oral anticoagulant’ OR ‘DOAC*’ OR Rivaroxaban OR Apixaban OR Dabigatran OR Edoxaban) AND ABS (‘hip fracture’ OR ‘hip surgery’) AND (postoperative* OR mortality OR ‘time to surgery’ OR ‘length of stay’ OR ‘complication*’ OR bleed* OR ‘blood loss’ OR embolism OR thrombosis OR ‘intensive care*’) (see Appendix 1 for full search strategy).

Articles were excluded if patients did not have surgery after their hip fracture, patients were not taking DOACs pre-operatively (other than comparator populations), if the article was a systematic review, other type of review, a single case report, a study protocol, or if there was insufficient detail regarding the health outcome(s) examined. Results were limited to English-language articles that were published in peer-review journals from 1 January 2000 to 31 August 2021. Snowballing of article reference lists and review of co-author repositories was conducted to identify any potential articles not previously identified.

Abstract screening

The full citation information including title and abstract of each article identified during the database searches was imported into Endnote X20 and duplicates removed. The abstracts were independently assessed for inclusion by two reviewers (SJ, NH), who met regularly to discuss any uncertainties. If the abstract did not report that the research evaluated the impact of pre-operative DOACs on patient health outcomes after hip fracture surgery it was excluded. Both reviewers (SJ, NH) screened 15.0% of the articles and the interrater percent agreement was 82.9%. Any disagreements on abstract inclusion were discussed with a third reviewer (RM) and consensus achieved.

Full-text screening, data extraction and quality review

The full text of each article was assessed by two reviewers (SJ, NH), if the article was included in the abstract review stage. Any article that did not meet the inclusion criteria was excluded. For articles that met the inclusion criteria, key information was extracted from each article during the full-text review by two reviewers (SJ, NH), including: authors and publication year; review objective/aim; study type, country and time frame examined, population and sample size, type of DOACs examined, comparator population(s), health outcome(s), and summary study findings. Data extraction results were independently appraised for accuracy by a third author (RM). The methodological quality of the articles was assessed by two reviewers (SJ, NH) and appraised by a third reviewer (RM) using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) cohort [21] or case–control [22] study checklists, where applicable. The quality of retrospective matched case-comparison studies was assessed with the case–control study checklist. Any clarifications regarding methodological quality were discussed between reviewers.

Data synthesis

The information on the included studies in the data extraction table was compared and a data synthesis was undertaken by one reviewer (RM) and appraised by two reviewers (HS and ST). The data synthesis involved identifying the most common health outcomes examined for DOAC users versus the no anticoagulant use comparator group. The findings for each health outcome were summarised as to whether DOAC users had a worse outcome than a no anticoagulant comparator population, where possible. The data extraction and data synthesis results were examined by two authors (HS and ST) and whether any recommendations could be made regarding the pre-operative use of DOACs and the timing of hip fracture surgery based on the existing research evidence was considered (Supplementary Table 1).

Results

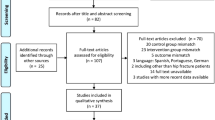

A total of 318 articles were identified during the database searches. After removing duplicates, 233 articles remained. After abstract review, 34 full-text articles were examined, along with 11 articles from snowballing. A final 21 articles were included in the rapid review (Fig. 1).

Study type, country and comparator population

Around three-quarters (76.2%) were retrospective cohort studies, with five (23.8%) case–control/comparison designs. The number of patients taking DOACs in the studies ranged from 11 to 1063, with a median of 33 patients. Three (14.3%) studies each were conducted in Australia, the United Kingdom (UK), Israel, and the United States (US), two (9.5%) each in Canada, Germany and Norway, and one (4.8%) study each in Austria, Denmark and Italy. Ten (47.6%) studies used two comparison groups, seven (33.3%) used one comparison group, two (9.5%) studies used three comparison groups and two (9.5%) studies used four comparison groups. The comparison groups involved patients not taking any anticoagulants pre-surgery (n = 18 groups), patients taking VKAs (n = 14 groups), and patients taking PAIs (n = 7 groups).

Patient age and common health outcomes

The age inclusion criteria varied for patients, eight (38.1%) studies included patients aged ≥ 65 years, four (19.0%) studies included patients aged ≥ 60 years, one (4.8%) study included patients aged > 70 years, five (23.8%) studies did not specify their patient age inclusion criteria, but the mean age of patients in these studies was in the mid-80 s. Where indicated, the mean patient age ranged from 80.7 to 85.0 years and median age ranged from 83.5 to 86.0 years (Table 1).

The most common health outcomes examined were time to surgery (100%), mortality (95.2%; n = 20), blood loss (76.2%; n = 16), post-operative complications (52.4%; n = 11) and hospital LOS (47.6%; n = 10). Type of anaesthesia used during surgery was only recorded in five (23.8%) studies. Information regarding when DOAC use ceased prior to surgery was not often recorded (9.5%; n = 2).

Time to surgery

Time to surgery (either exact or within < 48 h was not defined in six (30.0%) studies. Of the 18 studies that examined exact time to surgery, 12 (57.1%) identified that DOAC users had a longer time to surgery, 5 (23.8%) found no difference in time to surgery, and 1 (4.8%) study identified a longer time to surgery for closed reduction internal fixation, but not for hemiarthroplasty compared to patients not using anticoagulants prior to surgery. Five (83.3%) of six studies identified that DOAC users had a lower proportion of surgeries conducted within 48 h compared to patients not using anticoagulants.

Blood loss and transfusions

Blood loss definitions varied and none of the nine studies that reported blood loss found a difference in blood loss between patients using DOACs versus no anticoagulants. Only 2 (18.2%) of the 11 studies that reported on the proportion of transfusions between DOACs compared to patients not using anticoagulants found a higher proportion of blood transfusions for patients using DOACs.

Post-operative complications and hospital LOS

No difference was found in post-operative complication rates for the eight studies that reported on complications and no difference was found for the three studies that reported on the incidence of stroke between DOAC users and patients not using anticoagulants. One (50.0%) of two studies that reported on wound ooze (defined as clinically identified ooze with or without bleeding) found a higher proportion of ooze for DOAC users versus patients not using anticoagulants. One (14.3%) of the seven studies that reported on re-operations/readmissions identified a higher proportion of readmissions for DOAC users, compared to patients not using anticoagulants. Four (40.0%) of the ten studies that reported on hospital LOS identified a higher LOS for DOAC users.

Mortality

Seven (87.5%) of 8 studies that reported in-hospital mortality, 12 (92.3%) of 13 studies that reported 30-day mortality, and 6 (85.7%) of 7 studies that reported mortality at 1-year identified no difference in mortality rates for DOAC users compared to patients not using anticoagulants. One (14.3%) study identified a higher 1-year mortality for DOAC users for closed reduction internal fixation, but not for hemiarthroplasty compared to patients not using anticoagulants.

Quality assessment

Methodological quality assessment measures for articles varied and few studies (38.1%; n = 8) received all ‘Yes’ ratings (Tables 2 and 3).

CASP Appraisal Checklist questions

1. Did the study address a clearly focussed issue? | 6b. Was the follow-up of subjects long enough? |

2. Was the cohort recruited in an acceptable way? | 7. What are the results of this study? |

3. Was the exposure accurately measured to minimise bias? | 8. How precise are the results? |

4. Was the outcome accurately measured to minimise bias? | 9. Do you believe the results? |

5a. Have the authors identified all important confounding factors? | 10. Can the results be applied to the local population? |

5b. Have they taken into account the confounding factors in the design and/or analysis? | 11. Do the results of this study fit with other available evidence? |

6a. Was the follow-up of the subjects complete enough? | 12. Does the study have implications for practice? |

CASP Appraisal Checklist questions

1. Did the study address a clearly focussed issue? | 6b. Have the authors taken account of the potential confounding factors in the design and/or in their analysis? |

2. Did the authors use an appropriate method to answer their question? | 7. How large was the treatment effect? |

3. Were the cases recruited in an acceptable way? | 8. How precise was the estimate of the treatment effect? |

4. Were the controls selected in an acceptable way? | 9. Do you believe the results? |

5. Was the exposure accurately measured to minimise bias? | 10. Can the results be applied to the local population? |

6a. Aside from the experimental intervention, were the groups treated equally? | 11. Do the results of this study fit with other available evidence? |

Discussion

This rapid review identified 21 studies that examined the impact of pre-operative DOAC use on hip fracture patients’ health outcomes. Overall, in these studies the effect of DOAC use on hip fracture patient health outcomes compared to patients not taking any anticoagulants was mixed. Compared to patients not taking anticoagulants, in 57.1% of studies DOAC users had a longer time to surgery, 40.0% had a longer hospital LOS, 18.2% had a higher proportion of blood transfusions, and 14.3% had a higher proportion of readmissions, where each of these outcomes was examined. No difference was identified in overall blood loss, post-operative complication rates, stroke, or in-hospital, 30-day or 1-year mortality between DOAC users and patients not taking any anticoagulants in studies that examined these patient outcomes.

The advantages of using DOACs are that they are taken orally and are associated with fewer dietary and other medication interactions [10, 23]. DOACs have a fast therapeutic onset, lower complication and monitoring requirements, and are more cost-effective compared to VKAs, such as warfarin [10, 24]. A systematic review and meta-analysis that examined the effect of DOAC or VKA use on time to surgery and mortality for hip fracture patients found that time to surgery was 15.5 h longer for patients taking DOACs than patients not on anticoagulants, with no difference in time to surgery for patients taking DOACs versus VKAs, and that there was no difference in in-hospital mortality for patients taking DOACs compared to patients not on anticoagulants [25].

While this rapid review found that time to surgery was reported as longer for patients using DOACs pre-operatively, whether or not the surgery was conducted within 48 h was only examined by one-third of studies, with five of six studies identifying a lower proportion of surgery conducted within 48 h for patients taking DOACs versus no anticoagulants. Prior research has largely indicated that better health outcomes after hip fracture surgery are associated with surgery that is conducted within 48 h of patient admission [5,6,7,8]. In one study, hip fracture surgery for DOAC users within 24 h of admission was not associated with increased blood loss, transfusion rates or 30-day mortality compared to matched patients not taking anticoagulants [26]. However, larger population-based studies are needed to further examine patient outcomes for DOAC users undergoing surgery < 24 h after admission.

The current review found no difference in overall blood loss or post-operative complication rates, and only two studies consistently identified higher mortality rates for hip fracture patients taking DOACs versus no anticoagulants. Prior systematic reviews and meta-analyses of health outcomes of DOACs users compared to patients taking VKAs not limited to trauma found that DOAC users had a reduced patient complication and mortality risk, and showed no difference in blood loss [27,28,29,30], except for dabigatran which was associated with a higher risk of gastrointestinal bleeding compared to VKAs [31]. That there was no difference found for patients taking DOACs versus no anticoagulants for mortality, post-operative complications or blood loss may stem in part from a delayed time to surgery for patients taking DOACs as surgical teams aim to optimise these patients prior to surgery to achieve the best outcomes possible. Given a randomised controlled trial is unlikely to take place, and there are large clinical hip fracture registries in a number of countries which measure high-level outcomes in hip fracture patients, developing a consensus and monitoring approach for time to surgery for patients taking DOACs may guide practice in the future.

Published reviews and practical guidelines have indicated there is no consensus on an appropriate DOAC free period prior to acute hip fracture surgery [32,33,34]. The recommended time to surgery in guidelines has ranged from 12 h after the last dose to up to 4 days, depending on half-life of the DOAC and patient renal function [32,33,34,35]. Most recommendations on time to surgery for patients pre-operatively taking DOACs have been made for patients undergoing elective surgery [32], and there has been limited examination of DOACs and time to surgery in the acute care setting, such as for hip fracture.

This systematic rapid review has identified that the research evidence surrounding pre-operative DOAC use and time to surgery is mainly derived from retrospective cohort studies conducted at single facilities which describe current varied practice. The review identified limited evidence to support the development of practical clinical guidelines on the management of hip fracture patients taking DOACs. These studies indicate that almost two-thirds of DOAC users are delayed to hip fracture surgery compared to patients not taking any anticoagulants. Whether a delay to surgery for hip fracture patients taking DOACs pre-operatively is justified needs further clarification from robust, large population-based studies [32, 35], along with further pragmatic investigation of the use of reversal agents for DOACs prior to acute hip fracture surgery [36].

This rapid review has also shown there is a need for consistency in the type of health outcomes examined post-hip fracture surgery to determine the effect of DOACs on patient outcomes. This includes providing clear definitions for each health outcome examined, particularly for the measurement of blood loss, noting the hours prior to surgery that DOAC use ceased, the type of anaesthesia used during surgery, and the specific type of post-operative complications examined. In six (33.3%) studies in this review [26, 37,38,39,40,41], a matched comparison group was used or data were matched post hoc, but matching criteria were not consistent across studies, nor were consistent comparator groups used. Where matching was not used, only six (40.0%) studies specified and adjusted for potential covariates [42,43,44,45,46,47], indicating potential limitations of sample size to conduct regression analyses. In ten (47.6%) studies, there were less than 50 patients taking DOACs.

With the ageing population and the growth of chronic diseases, the use of DOACs in older hip fracture patients is likely to increase [9]. Further pragmatic research is needed to examine the impact of pre-operative DOAC use on hip fracture patient health outcomes, including examining patient experience measures along with patient-reported outcome measures, particularly regarding HRQoL and ADLs.

The strengths of this rapid review were that it followed the PRISMA guidelines, it used a comprehensive keyword search strategy involving three databases, a university medical librarian assisted with the development of the keyword search terms, and multiple reviewers were involved in the data extraction phase with high interrater reliability. Any clarifications or disagreements were discussed between reviewers and consensus was obtained. However, there were some limitations of the review. Studies published in non-English languages were excluded, which may result in language bias. The rapid review did not examine clinical trials registries, so any trials currently underway were excluded. Three studies included patients aged < 65 years; however the mean patient age in these studies was in the 80 s, warranting their inclusion.

Conclusions

This review found limited evidence to support guidelines on the management of hip fracture patients taking DOACs. The effect of DOAC use on hip fracture patient health outcomes compared to patients not taking any anticoagulants was mixed, although patients on DOACs had a longer time to surgery. It highlights the need for robust, population-based studies and the consistent examination of hip fracture surgery health outcomes to determine the most appropriate management of patients with a hip fracture taking a DOAC.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Sharma S, Mueller C, Stewart R, Veronese N, Vancampfort D, Koyanagi A, Lamb S, Perera G, Stubbs B. Predictors of falls and fractures leading to hospitalization in people with dementia: a representative cohort study. J Am Med Directors Assoc. 2018.

Abrahamsen B, Van Staa T, Ariely R, Olson M, Cooper C. Excess mortality following hip fracture: a systematic epidemiological review. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1633–50.

Lystad R, Cameron C, Mitchell R. Mortality risk among older Australians hospitalised with hip fracture: a population-based matched cohort study. Arch Osteoporos. 2017;12:67.

Dyer S, Crotty M, Fairhall N, Magaziner J, Beaupre L, Cameron I, Sherrington C. A critical review of the long-term disability outcomes following hip fracture. BMC Geriatr. 2017;16:158.

Moja L, Piatti A, Pecoraro V, Ricci C, Virgili G, Salanti G, Germagnoli L, Liberati A, Banfi G. Timing matters in hip fracture surgery: patients operated within 48 hours have better outcomes. A meta-analysis and meta-regression of over 190,000 patients. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46175.

Leer-Salvesen S, Engesæter LB, Dybvik E, Furnes O, Kristensen TB, Gjertsen J-E. Does time from fracture to surgery affect mortality and intraoperative medical complications for hip fracture patients? An observational study of 73 557 patients reported to the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register. Bone Joint J. 2019;101:1129–37.

Klestil T, Röder C, Stotter C, Winkler B, Nehrer S, Lutz M, Klerings I, Wagner G, Gartlehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B. Impact of timing of surgery in elderly hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1–15.

Orosz GM, Magaziner J, Hannan EL, Morrison RS, Koval K, Gilbert M, McLaughlin M, Halm EA, Wang JJ, Litke A. Association of timing of surgery for hip fracture and patient outcomes. JAMA. 2004;291:1738–43.

Damanti S, Braham S, Pasina L. Anticoagulation in frail older people. J Geriatr Cardiol: JGC. 2019;16:844–6.

Taranu R, Redclift C, Williams P, Diament M, Tate A, Maddox J, Wilson F, Eardley W. Use of anticoagulants remains a significant threat to timely hip fracture surgery. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2018;9:2151459318764150.

Caruso G, Andreotti M, Marko T, Tonon F, Corradi N, Rizzato D, Valentini A, Valpiani G, Massari L. The impact of warfarin on operative delay and 1-year mortality in elderly patients with hip fracture: a retrospective observational study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14:1–9.

Lott A, Haglin J, Belayneh R, Konda SR, Leucht P, Egol KA. Surgical delay is not warranted for patients with hip fractures receiving non-warfarin anticoagulants. Orthopedics. 2019;42:e331–5.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, The management of hip fracture in adults, 2011, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London.

Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry Steering Group, Australian and New Zealand Guideline for Hip Fracture Care, 2014, Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry Steering Group: Sydney.

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Management of hip fractures in the elderly. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline, 2014, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: Rosemont, IL.

Borges FK, Bhandari M, Guerra-Farfan E, Patel A, Sigamani A, Umer M, Tiboni ME, del Mar Villar-Casares M, Tandon V, Tomas-Hernandez J. Accelerated surgery versus standard care in hip fracture (HIP ATTACK): an international, randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet. 2020;395:698–708.

Lizaur-Utrilla A, Martinez-Mendez D, Collados-Maestre I, Miralles-Muñoz FA, Marco-Gomez L, Lopez-Prats FA. Early surgery within 2 days for hip fracture is not reliable as healthcare quality indicator. Injury. 2016;47:1530–5.

Dailiana Z, Papakostidou I, Varitimidis S, Michalitsis S, Veloni A, Malizos K. Surgical treatment of hip fractures: factors influencing mortality. Hippokratia. 2013;17:252.

Fohtung RB, Novak E, Rich MW. Effect of new oral anticoagulants on prescribing practices for atrial fibrillation in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:2405–12.

Harvey N, Dennison E, Cooper C. Osteoporosis: impact on health and economics. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:99–105.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Cohort study checklist. 2018 [cited 2021 6/10/2021]; Available from: https://casp-uk.net/.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP case–control study checklist. 2018 [cited 2021 6/10/2021]; Available from: https://casp-uk.net/.

Cherubini A, Carrieri B, Marinelli P. Advantages and disadvantages of direct oral anticoagulants in older patients. Geriatr Care. 2018; 4.

Liew A, Douketis J. Perioperative management of patients who are receiving a novel oral anticoagulant. Intern Emerg Med. 2013;8:477–84.

You D, Xu Y, Ponich B, Ronksley P, Skeith L, Korley R, Carrier M, Schneider PS. Effect of oral anticoagulant use on surgical delay and mortality in hip fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone Joint J. 2021;103:222–33.

Mullins B, Akehurst H, Slattery D, Chesser T. Should surgery be delayed in patients taking direct oral anticoagulants who suffer a hip fracture? A retrospective, case-controlled observational study at a UK major trauma centre. BMJ Open. 2018; 8.

Sardar P, Chatterjee S, Chaudhari S, Lip GY. New oral anticoagulants in elderly adults: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:857–64.

Sadlon, AH and Tsakiris, DA. Direct oral anticoagulants in the elderly: systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence, current and future directions. Swiss Med Weekly. 2016; 146.

Grymonprez M, Steurbaut S, De Backer TL, Petrovic M, Lahousse L. Effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants in older patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1408.

Amin A, Garcia Reeves AB, Li X, Dhamane A, Luo X, Di Fusco M, Nadkarni A, Friend K, Rosenblatt L, Mardekian J. Effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants in older adults with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and heart failure. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0213614.

Sharma M, Cornelius VR, Patel JP, Davies JG, Molokhia M. Efficacy and harms of direct oral anticoagulants in the elderly for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism: systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2015;132:194–204.

Papachristos IV, Giannoudis PV. Proximal femur fractures in patients taking anticoagulants. EFORT Open Rev. 2020;5:699–706.

Shah R, Sheikh N, Mangwani J, Morgan N, Khairandish H. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) and neck of femur fractures: standardising the perioperative management and time to surgery. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2021;12:138–47.

Steffel J, Verhamme P, Potpara TS, Albaladejo P, Antz M, Desteghe L, Haeusler KG, Oldgren J, Reinecke H, Roldan-Schilling V. The 2018 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:1330–93.

Griffiths R, Babu S, Dixon P, Freeman N, Hurford D, Kelleher E, Moppett I, Ray D, Sahota O, Shields M. Guideline for the management of hip fractures 2020: Guideline by the Association of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2021;76:225–37.

Chaudhary R, Sharma T, Garg J, Sukhi A, Bliden K, Tantry U, Turagam M, Lakkireddy D, Gurbel P. Direct oral anticoagulants: a review on the current role and scope of reversal agents. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;49:271–86.

Franklin NA, Ali AH, Hurley RK, Mir HR, Beltran MJ. Outcomes of early surgical intervention in geriatric proximal femur fractures among patients receiving direct oral anticoagulation. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32:269–73.

King K, Polischuk M, Lynch G, Gergis A, Rajesh A, Shelfoon C, Kattar N, Sriselvakumar S, Cooke C. Early surgical fixation for hip fractures in patients taking direct oral anticoagulation: a retrospective cohort study. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2020; 11.

Tarrant SM, Catanach MJ, Sarrami M, Clapham M, Attia J, Balogh ZJ. Direct oral anticoagulants and timing of hip fracture surgery. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2200.

Mahmood A, Thornton L, Whittam DG, Maskell P, Hawkes DH, Harrison WJ. Pre-injury use of antiplatelet and anticoagulations therapy are associated with increased mortality in a cohort of 1038 hip fracture patients. Injury. 2021;52:1473–9.

Rostagno C, Cartei A, Polidori G, Civinini R, Ceccofiglio A, Rubbieri G, Curcio M, Boccaccini A, Peris A, Prisco D. Management of ongoing direct anticoagulant treatment in patients with hip fracture. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1–6.

Hourston GJM, Barrett MP, Khan WS, Vindlacheruvu M, McDonnell SM. New drug, new problem: do hip fracture patients taking NOACs experience delayed surgery, longer hospital stay, or poorer outcomes? Hip Int. 2020;30:799–804.

Leer-Salvesen S, Dybvik E, Ranhoff AH, Husebo BL, Dahl OE, Engesaeter LB, Gjertsen JE. Do direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) cause delayed surgery, longer length of hospital stay, and poorer outcome for hip fracture patients? Eur Geriatr Med. 2020;11:563–9.

Saliba W, Arbel A, Abu-Full Z, Cohen S, Rennert G, Preis M. Preoperative direct oral anticoagulants treatment and all-cause mortality in elderly patients with hip fracture: a retrospective cohort study. Thromb Res. 2020;189:48–54.

Schermann H, Gurel R, Gold A, Maman E, Dolkart O, Steinberg EL, Chechik O. Safety of urgent hip fracture surgery protocol under influence of direct oral anticoagulation medications. Injury. 2019;50:398–402.

Schuetze K, Eickhoff A, Dehner C, Gebhard F, Richter PH. Impact of oral anticoagulation on proximal femur fractures treated within 24h—a retrospective chart review. Injury. 2019;50:2040–4.

Daugaard C, Pedersen AB, Kristensen N, Johnsen S. Preoperative antithrombotic therapy and risk of blood transfusion and mortality following hip fracture surgery: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30:583–91.

Bruckbauer M, Prexl O, Voelckel W, Ziegler B, Grottke O, Maegele M, Schochl H. Impact of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with hip fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;33:e8–13.

Cafaro T, Simard C, Tagalakis V, Koolian M. Delayed time to emergency hip surgery in patients taking oral anticoagulants. Thromb Res. 2019;184:110–4.

Creeper K, Stafford A, Reynolds S, Samida S, P’Ng S, Glennon D, Seymour H, Grove C. Outcomes and anticoagulation use for elderly patients that present with an Acute Hip Fracture: multi‐centre, retrospective analysis. Int Med J. 2020.

Frenkel Rutenberg T, Velkes S, Vitenberg M, Leader A, Halavy Y, Raanani P, Yassin M, Spectre G. Morbidity and mortality after fragility hip fracture surgery in patients receiving vitamin K antagonists and direct oral anticoagulants. Thromb Res. 2018;166:106–12.

Gosch M, Jacobs M, Bail H, Grueninger S, Wicklein S. Outcome of older hip fracture patients on anticoagulation: a comparison of vitamin K-antagonists and Factor Xa inhibitors. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021;141:637–43.

Shani M, Yahalom R, Comaneshter D, Holtzman K, Blickstein D, Cohen A, Lustman A. Should patients treated with oral anti-coagulants be operated on within 48 h of hip fracture? J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021;51:1132–7.

Tran T, Delluc A, de Wit C, Petrcich W, Le Gal G, Carrier M. The impact of oral anticoagulation on time to surgery in patients hospitalized with hip fracture. Thromb Res. 2015;136:962–5.

Viktil KK, Lehre I, Ranhoff AH, Molden E. Serum concentrations and elimination rates of direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in older hip fracture patients hospitalized for surgery: a pilot study. Drugs Aging. 2019;36:65–71.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms Mary Simons, medical research librarian, for their expertise and guidance regarding the development of the search terminology.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This research did not receive any specific Grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. SJ conducted the database searches. SJ and NH conducted abstract, full-text screening and quality reviews. RM appraised the full-text screening and quality review results and conducted the data synthesis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by RM and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix 1: Search strategy for each database

Appendix 1: Search strategy for each database

Medline

“Exp Anticoagulants/” OR “Administration, Oral/” OR “Hip Fractures/su [Surgery]” OR “1 and 3” AND “limit 4 to "all aged (65 and over)" AND limit 5 to (“middle aged (45 plus years)” OR “all aged (65 and over)”) AND “limit 6 to (English language and (clinical trial, all” OR “randomized controlled trial” OR “systematic review”)).

Embase

“Exp hip fracture” OR “exp anticoagulant agent/” OR “1 and 2” OR “exp postoperative period/” OR “3 and 4” OR “(surgery or surgical).tw.” OR “1 and 6” OR “2 and 7” OR “4 and 8” AND “limit 9 to (English language and (clinical trial or randomized controlled trial))” AND “limit 12 to (English language and yr = “2011–2022”)”.

Scopus

(TITLE-ABS-KEY (anticoagulant* OR “oral anticoagulant” ORr “DOAC*” OR Rivaroxaban OR Apixaban OR Dabigatran OR Edoxaban) AND ABS (“hip fracture” OR “hip surgery”) AND ABS (postoperative* OR mortality OR “time to surgery” OR “length of stay” OR “complication*” OR bleed* OR “blood loss” OR embolism OR thrombosis OR “intensive care*”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mitchell, R.J., Jakobs, S., Halim, N. et al. Synthesis of the evidence on the impact of pre-operative direct oral anticoagulants on patient health outcomes after hip fracture surgery: rapid systematic review. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 48, 2567–2587 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-022-01937-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-022-01937-8