Abstract

Purpose

Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) can manifest as fungus balls in preexisting cavities of lung parenchyma and recurrent hemoptysis is among the most frequent complications. Radiotherapy can be considered for treatment-refractory aspergilloma and severe hemoptysis. To the best of our knowledge, we present the first application of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for a pulmonary aspergilloma in a patient with limited functional lung capacity. The topic was further expanded on with a systematic review of the literature addressing the implementation of radiotherapy in CPA patients.

Case report

A 52-year-old man presented with recurring and treatment-refractory hemoptysis caused by chronic cavitary aspergillosis localized in the left lower lobe. We applied SBRT on two consecutive days with a total dose of 16 Gy. Hemoptysis frequency decreased to a clinically insignificant level.

Systematic review

We performed a systematic search of the literature in line with the PRISMA statement. The initial PubMed search resulted in 230 articles, of which 9 were included.

Results

The available literature contained 35 patients with CPA who received radiotherapy. Dose fractionation usually ranged from 2 to 4 Gy per fraction, applied almost exclusively in conventional two-dimensional (2D) techniques. There is no report of SBRT usage in such a scenario. Most cases report a positive treatment response after irradiation.

Conclusion

The presented case demonstrates long-term clinical stability after SBRT for recurrent hemoptysis due to pulmonary aspergilloma. The systematic literature search revealed that concept definition is still uncertain, and further work is necessary to establish radiotherapy in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pulmonary aspergillosis can be subdivided into allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA), and chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) [1]. While ABPA is characterized by inflammatory immune-mediated pulmonary processes caused by exposure to Aspergillus antigens, IPA is an acute and severe fungal infection of the lung, mostly affecting heavily immunocompromised patients treated with chemotherapy and/or immunosuppressive therapies for conditions such as hematologic malignancies, solid tumors, or organ transplantations [1, 2]. Invasive growth of the Aspergillus hyphae can even lead to hematogenous dissemination to distant organs including the central nervous system [1]. In contrast, CPA usually affects immunocompetent individuals with underlying pulmonary diseases. Risk factors include pulmonary tuberculosis (TB), which is the most frequent predisposing factor, but also other diseases causing pulmonary fibrosis and cavity formation such as treated lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or fibrocystic sarcoidosis [3, 4]. CPA itself comprises different forms of long-term fungal infections of the lung, varying in clinical manifestation and severity. Chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis (CCPA) and chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis (CFPA)—its terminal evolution if left untreated—are the most frequent entities. CPA is most commonly caused by Aspergillus fumigatus. After colonization of pre-existing pulmonary cavities, it usually presents with aspergillomas, which are composed of fungal hyphae, inflammatory cells, extracellular matrix, and necrotic material [3, 5]. Clinically, CPA manifests with chronic cough, breathlessness, chest pain, fever, weight loss, and hemoptysis. The latter occurs in more than 60% of patients [6]. For diagnosis of CPA, symptoms have to persist for at least 3 months. Besides that, diagnosis of CPA involves microbiological or serological evidence of an Aspergillus infection and exclusion of other explanations and suspicious findings in thoracic imaging [3]. Gold standard imaging is CT angiography to precisely localize the aspergilloma and detect possible infiltration of the surrounding vasculature. The affected cavities can vary in wall thickness and contain one or even more fungus balls, often surrounded by a characteristic crescent of air [3]. Surgical resection is considered the preferred and a potentially curative option for symptomatic patients with sufficient respiratory reserve and unilateral or localized manifestations [3, 4, 7]. Additionally, surgery should always be considered in cases of severe hemoptysis [3]. Additionally, long-term antifungal pharmacotherapy with azole derivates or amphotericin B is also recommended for patients with CPA to reduce respiratory symptoms and prevent disease progression [7, 8]. Antifungal medication can also be directly administered into a symptomatic aspergilloma cavity via CT-guided percutaneous or endobronchial instillation [4]. In refractory cases or massive hemoptysis, which occasionally can become life-threatening, bronchial artery embolization (BAE) is an option to stop the bleeding in patients unfit for surgery. However, the recurrence rate of hemoptysis in patients with CPA after BAE is more than 50% [9]. Radiotherapy, on the other hand, is not yet mentioned in the latest multidisciplinary consensus guidelines [7] and currently only considered an option for treatment-refractory aspergilloma and extensive hemoptysis by a small number of clinicians according to the screened literature. To the best of our knowledge, we present the first application of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for a pulmonary aspergilloma, delivered with a robotic technique in a patient with limited functional lung capacity. The topic is further expanded on with a systematic review of the literature.

Methods

Case report

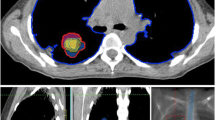

In 2015, a then 52-year-old man was referred to our radiation oncology department for evaluation of hemostatic treatment. He presented with chest pain, dyspnea, fatigue, loss of appetite, weight loss, recurrent respiratory infections, and episodes of significant hemoptysis. Medical history included pulmonary TB in 1995 (Fig. 1), which was adequately treated with antitubercular medications for 6 months, resulting in a residual cavity in the left lower lobe. Hemoptysis first occurred a couple of years after initial TB treatment and symptoms had become aggravated since then. In 2007, the patient presented with a new episode of hemoptysis. His medical history and a CT scan of the chest lead to the differential diagnosis of pulmonary aspergillosis. The patient was hemodynamically stable and a hemoglobin of 155 g/L (reference value 135–168 g/L) was measured. Since bronchoscopy confirmed endobronchial bleeding from the segments where the lesion was located, partial resection of the left inferior lobe was performed in the same year. Aspergilloma was confirmed by histopathological examination of the resected lung tissue. A post-interventional CT scan of the chest, however, showed persistence of the aspergilloma. In addition, persistence was suggested microbiologically by positive Aspergillus cultures from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and sputum at different timepoints. In the following years, three attempts at endovascular embolization of pulmonary arteries, the first in 2008, were performed due to recurring hemoptysis, without achieving lasting hemostasis. Therefore, long-term antifungal therapy with itraconazole was initiated in 2009 and continued for 2.5 years. In addition to the aspergillosis, the patient was diagnosed with a pulmonary actinomycosis in 2015, a rare opportunistic bacterial infection of the lung. Actinomyces were also isolated from a bronchoscopic biopsy in the left lower lobe. Although Aspergillus cultures and Aspergillus precipitin could not reaffirm aspergilloma persistence at that time, these results did not definitely rule out a concomitant fungal and bacterial infection. The patient’s pulmonary function was further reduced after suffering multiple pulmonary emboli. The last complete pulmonary function testing prior to radiotherapy was performed in 2013. It revealed a vital capacity (VC) of 2.15 L (44% of reference value), forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) of 1.55 L (41%), and a diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) of 7.4 mmol/min/kPa (71%), so that the patient was considered unfit for further surgical interventions. During the first consultation in our clinic, the patient reported recurrent episodes of hemoptysis causing blood loss of more than 100 ml per day. A CT of the chest showed a persistent, spiculated, partly cavernous lesion in the left lower lobe with a diameter of approximately 5 cm (Fig. 2a). Treatment planning also included an 18F‑FDG-PET/CT scan to localize the fungal manifestation and identified the metabolically active inflamed vascular lining of the cavity as the most likely cause of bleeding (Fig. 3a). SBRT with a total dose of 16 Gy was applied in two fractions of 8 Gy on consecutive days with a robotic arm-mounted linear accelerator equipped with an iris collimator (CyberKnife®, Accuray Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA; Fig. 3b). Dose was prescribed to the 80% isodose line and the ray-tracing algorithm was used for dose calculation. After acquisition of a 4D-planning CT to account for respiratory motion, the planning target volume (PTV) was generated from an internal target volume (ITV), adding a 2-mm margin. Despite an irregularly shaped PTV, the chosen irradiation technique allowed us to achieve a conformal dose distribution of the target volume and tolerable doses for relevant organs at risk (OAR) as shown in the dose–volume histogram (DVH; Fig. 3c). The treatment was well tolerated, and no side effects were reported by the patient. During the 6 years of follow-up at our department, the patient has reported a significant decrease in hemoptysis frequency and volume, and no new long-term medication or invasive treatments have been necessary since then. When he presented at the hospital’s emergency unit with dyspnea and small-volume hemoptysis in 2016, there were no signs of an active or older bleeding evident in CT or bronchoscopy. Hemoglobin level remained stable at around 140 g/L over the years and fell below 120 g/L only once during an episode of community-acquired pneumonia in 2016 not accompanied by hemoptysis. Regular CT scans of the chest confirmed a stable size of the pulmonary lesion after an initial pseudoprogression, which is often observed after SBRT for large target volumes (Fig. 2b; [10]).

Timeline of important diagnostic and therapeutic steps. The upper part graphically shows onset and end of hemoptysis. The upward arrows indicate the most severe episodes of hemoptysis measured by bronchoscopic findings and patient-reported frequency and quantity. BAE bronchial artery embolization, CT computed tomography, SBRT stereotactic body radiotherapy

Pre- and postradiotherapy (RT) imaging. a Pre-RT thoracic CT scan 8 years after partial surgical resection of the left inferior lobe. The aspergilloma is localized adjacent to the great pulmonary vessels, showing the characteristic radiographic feature of the “air-crescent sign” (white arrow). b Aspergilloma decreased in size at 3‑year follow-up and no further interventions were necessary. After mild episodes of hemoptysis initially, no further episodes have been reported since then. CT computed tomography, RT radiotherapy

Treatment planning and modalities including dose–volume histogram (DVH). a Treatment planning included an 18F‑FDG-PET/CT scan to precisely localize the fungal manifestation and the primarily inflamed and eroded vascular lining of the cavity, most likely causing the bleeding. b 16 Gy was applied in two fractions of 8 Gy on consecutive days with a robotic arm-mounted linear accelerator. Dose was prescribed to the 80% isodose line. PTV (red) was generated from an ITV (green) by adding a 2-mm margin. The ITV accounts for motion of the target lesion during respiration registered by a 4D planning CT. The PTV on the other hand accounts for setup and planning uncertainties. c The DVH represents the exact radiation dose (shown as percentage of the prescribed dose) delivered to the target volumes and organs at risk (OAR; also shown as percentage of total volume). CT computed tomography, CTV clinical target volume, FDG fluorodeoxyglucose, ITV internal target volume, PET positron emission tomography, PTV planning target volume, RT radiotherapy

Systematic review

Search strategy and data collection

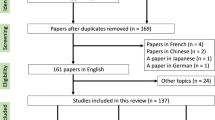

We performed a systematic search of the literature to find any reported cases of radiotherapy applied to patients with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Due to the limited number of reports, we also included case reports of individual patients. First, we conducted a PubMed search for reports including at least one of the possible combinations of the terms [“mycetoma” or “fung*” or “aspergill*”] and [“lung” or “haemopt*” or “bronchopulmonary” or “pulmonary”] and [“irradiat*” or “radiotherapy” or “radio-therapy” or “sbrt”] in the title or abstract without any limitations regarding the date of publication. Additionally, we performed a cross-reference search with Scopus and screened the databases of both the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) and the European Society for Radiation Oncology (ESTRO) for relevant congress abstracts. The literature search was performed in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement, meaning that findings were evaluated by two persons separately [11].

Results

The initial PubMed search delivered 230 results, of which only 5 fulfilled the thematic criteria. Four articles were manually added after cross-reference checking (Fig. 4). One Spanish article was also included after translation [12]. The final nine articles included 35 patients (Table 1), 21 of them reported in the largest case series so far by Sapienza et al. [13]. Where reported, radiotherapy was delivered in a 2D conventional technique, with opposed fields in most cases. Application of a 3D conformal technique with parallel opposed-oblique fields was only reported for one patient [14]. The prescribed doses ranged from 2 to 4 Gy per fraction, with total doses between 7 and 30 Gy (up to 34 Gy in case of recurrence) [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Weekly fractions of 3.5 Gy up to varying total doses have been reported by multiple authors [14, 18, 20]. Mean follow-up period across all reports was 4 years and 5 months. None of the studies reported any significant acute or late toxicities with exception of mild cough [13]. Sapienza et al. also reported an improvement of performance status in all patients 30 days after treatment. Almost all patients showed a lasting treatment response, either identified by a reduction of Aspergillus precipitin, disappearance of hemoptysis, or a decrease in aspergilloma size in chest imaging. Sapienza et al. calculated a 5-year local control rate of 82% [13]. One patient needed an increased dose of 34 Gy due to persistent hemoptysis after 20 Gy had initially been applied. Another patient of the same cohort was treated with a second course of 20 Gy after recurrence of bleeding [13]. As far as reported, only three of 35 patients died as a direct consequence of recurrent hemoptysis during the reported follow-up periods [13, 14].

Discussion

We present a first case of a CPA patient with recurrent hemoptysis despite previous surgery, bronchial artery embolization, and antifungal treatment, whose symptoms were finally controlled successfully by SBRT. As the literature contains only narrative reviews [4, 20] about radiotherapeutic treatment of CPA, we also performed a systematic review.

Hemoptysis is the most frequent and possibly life-threatening complication of CPA. Various treatment approaches have been reported aimed at controlling hemoptysis and disease progression in CPA. An estimated 3 million patients are affected by CPA worldwide. Approximately 20% of patients with post-tuberculosis cavities in the lung [21, 22] suffer from CPA. Therefore, CPA can be regarded as a global health burden, although detailed data of morbidity and mortality barely exist. In this context, it is possible that the utilization of radiotherapy to control hemoptysis in CPA is underreported in the literature.

Radiotherapy is already established as an efficient and well-tolerated option to control bleeding of tumors [23]. Hemostatic radiotherapy is thought to work by inducing edema, endothelial damage causing capillary necrosis, formation of thrombosis, and both vascular and perivascular fibrosis [4, 24]. It is currently not well established whether radiotherapy may additionally have a direct fungicidal effect. Aspergillus species can be inactivated by ultraviolet light and visible light irradiation of certain wavelengths can alter their metabolism, growth, and toxin production [25, 26]. A dose–response relationship has been reported for gamma rays. Doses of 10 and 50 Gy increased the in vitro growth of different fungi species, not including Aspergillus fumigatus, whereas higher doses of 1000 and 5000 Gy inactivated protein and polysaccharide synthesis [27]. Agricultural studies also show that gamma-irradiation with doses in the magnitude of kGy can be used for effectively decreasing fungal contamination [28, 29]. This might indicate that the lower doses usually applied in patients may not have a direct antifungal effect. However, fungal radioresistance varies greatly between species and the in vivo effect of radiation-induced tissue reaction on growth and metabolism of Aspergillus fumigatus has not been widely studied.

Consequently, the ideal dose fractionation for hemostatic radiotherapy is still discussed controversially. Depending on tumor entity, anatomic localization, and severity of bleeding, fractionation schemes are typically in the range of 10 × 2 Gy, 4–13 × 3 Gy, 3–6 × 4 Gy, or 4–5 × 5 Gy [23]. However, short-course hypofractionated schemes such as 1 × 8 Gy were shown to achieve equal bleeding control of approximately 90%, with lower risks of treatment interruption, incompliance, and hospitalization [30]. A single fraction of 8 Gy also emerged as the preferred scheme for hemoptysis in a large survey among Dutch radiation oncologists [31]. The reported fractionation schemes used for patients with hemoptysis caused by CPA may have been guided by the established and conservative hemostatic schemes. In contrast, we applied an escalated dose of 2 × 8 Gy on consecutive days in the reported case with great success and no reported side effects. This was chosen in consideration of the younger patient age and the fact that this was not a palliative cancer setting. In general, hypofractionation with SBRT also has logistic advantages and can spare a patient with limited respiratory reserve multiple trips to the hospital. The stereotactic technique and the localization of the pulmonary lesion further allowed us to avoid excess doses to organs at risk (Fig. 3c). However, precise treatment planning, dose calculation and treatment delivery is a necessity when performing SBRT to larger targets to avoid excess toxicity, especially in cases of centrally located thoracic target volumes. Some reports indicate an increased risk of pneumonitis, bronchopulmonary hemorrhage, fistulation, or neuropathy [32, 33]. Radiation-induced edema might also cause transient dyspnea. However, these studies applied considerably higher doses of at least 8 × 5 Gy or even 7 × 8 Gy in an oncologic setting. On the other hand, for more peripherally located thoracic tumors, even SBRT with one to three fractions with higher biologically equivalent doses did not result in an increase in major toxicity [34]. We therefore did not expect major side effects for the chosen fractionation in our case. Moreover, there is no plausible radiobiological explanation not to apply the dose hypofractionated or as a single fraction in this setting, because there is no known alpha/beta ratio difference between the target volume (i.e. fungus-infested tissue) and the tissue in its vicinity to exploit in order to protect the healthy tissue.

Notably, young age, blood-tinged sputum, and thick wall cavities have been identified as independent risk factors for severe hemoptysis in patients with aspergilloma [35]. The fact that the configuration of the cavity wall but not the initial size of the fungus ball is an independent prognostic marker might also speak for the beneficial use of additional 18F‑FDG-PET/CT imaging to identify particularly eroded and inflamed parts of this critical area. PET imaging has already become an essential part of the daily routine in radiation oncology [36]. In fact, it is also implemented in the management of invasive fungal infections for evaluating disease activity, expansion, and treatment response to antifungal agents [37, 38]. Regarding other radiologic modalities, respiratory-gated thoracic MRI imaging may also offer potential benefits for treatment planning by helping to identify eroded and affected parts of the aspergilloma wall with increased spatial resolution.

Comparing hemostatic radiotherapy to BAE as the current standard of care for hemoptysis in patients unfit for surgical interventions, both treatment modalities show great efficacy. Independent of the etiology of bleeding, BAE is particularly efficient for immediate hemostasis, with complete cessation of massive hemoptysis within the first 24 h in 85–96% of patients. However, rare but severe complications such as strokes, transient ischemic attacks, and transient quadriplegia are reported in some patients following BAE [39, 40]. Therefore, while BAE is the standard for acute and life-threatening cases of hemoptysis, hemostatic radiotherapy may be suitable for less severe scenarios and consolidation after initial BAE to prevent recurrence and the necessity of multiple interventions.

One obvious limitation of the present work is the limited number of reported cases. Given the favorable benefit–risk profile, larger studies of hemostatic radiotherapy in patients with aspergillosis appear viable. The CPAnet database is a prospective clinical register which is currently trying to improve the evidence base for management of CPA [41]. The direct antifungal effect of ionizing radiation, ideal dose and fractionation, and combination with BAE and/or antifungal medication would be of particular interest. Unfortunately, the highest burden of CPA is likely in low- and middle-income countries, where access to diagnostics and treatments like BAE, robotic linear accelerators, and PET/CT scanners may be limited, restricting treatment options for refractory cases of CPA with hemoptysis. However, while PET imaging may indeed be beneficial for target delineation, it is not indispensable, and SBRT can also be applied with most conventional gantry linear accelerators with sufficient precision in such scenarios.

Conclusion

We demonstrate the feasibility of long-term control of recurrent hemoptysis after SBRT due to CPA. SBRT ensured conformal dose delivery and acceptable radiation exposure of OARs for a large and irregularly shaped target volume. Further studies are necessary to identify the ideal dose fractionation and the most effective sequence when different conservative treatment modalities such as radiotherapy, BAE, and antifungal medication are combined. However, these are difficult to perform due to the relative scarcity of CPA cases in settings with adequate resources. An intensified interdisciplinary collaboration between pneumologists, thoracic surgeons, infectious disease specialists, and radiation oncologists, facilitated by case registries such as CPAnet, seems to be a good approach to improve treatment outcomes and gaining further insight into the optimal management of CPA.

Abbreviations

- ABPA:

-

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

- BAE:

-

Bronchial artery embolization

- CCPA:

-

Chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis

- CFPA:

-

Chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CPA:

-

Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CTV:

-

Clinical target volume

- DLCO:

-

Diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide

- DVH:

-

Dose–volume histogram

- 18F-FDG:

-

(18)F‑fluorodesoxyglucose

- FEV1 :

-

Forced expiratory volume in one second

- IPA:

-

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis

- ITV:

-

Internal target volume

- NR:

-

Not reported

- OAR:

-

Organs at risk

- PET:

-

Positron-emission tomography

- PTLD:

-

Post-tuberculosis lung disease

- PTV:

-

Planning target volume

- RT:

-

Radiotherapy

- SBRT:

-

Stereotactic body radiotherapy

- TB:

-

Pulmonary tuberculosis

- VC:

-

Vital capacity

References

Kanj A, Abdallah N, Soubani AO (2018) The spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Respir Med 141:121–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2018.06.029

Dandachi D, Dib R, Fernández-Cruz A, Jiang Y, Chaftari A‑M, Hachem R et al (2018) Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with solid tumours: risk factors and predictors of clinical outcomes. Ann Med 50(8):128. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2018.1518581

Denning DW, Cadranel J, Beigelman-Aubry C, Ader F, Chakrabarti A, Blot S et al (2016) Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management. Eur Respir J 47(1):45–68. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00583-2015

Lang M, Dai L, Chauhan N, Gill A (2020) Non-surgical treatment options for pulmonary aspergilloma. Respir Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2020.105903

Tochigi N, Okubo Y, Ando T, Wakayama M, Shinozaki M, Gocho K et al (2013) Histopathological implications of aspergillus infection in lung. Mediators Inflamm. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/809798

Hou X, Zhang H, Kou L, Lv W, Lu J, Li J (2017) Clinical features and diagnosis of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in Chinese patients. Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000008315

Ullmann AJ, Aguado JM, Arikan-Akdagli S, Denning DW, Groll AH, Lagrou K et al (2018) Diagnosis and management of aspergillus diseases: executive summary of the 2017 ESCMID-ECMM-ERS guideline. Clin Microbiol Infect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2018.01.002

Al-Shair K, Atherton GT, Harris C, Ratcliffe L, Newton PJ, Denning DW (2013) Long-term antifungal treatment improves health status in patients with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: a longitudinal analysis. Clin Infect Dis 57(6):828–835. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit411

Shin B, Koh W‑JJ, Shin SW, Jeong B‑HH, Park HY, Suh GY et al (2016) Outcomes of bronchial artery embolization for life-threatening hemoptysis in patients with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0168373

Dağdelen M, Akovalı ES, Barlas C, Can G, Dinçbaş FÖ (2021) Interobserver agreement between interpretations of acute changes after lung stereotactic body radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol 197(5):423–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-020-01711-y

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Fernández Vázquez E, Zamarrón Sanz C, Alvarez Dobaño JM, Penela Penela P, González Patiño E (1994) Hemoptysis caused by aspergilloma treated with radiotherapy. An Med Interna 11(10):516–517

Sapienza LG, Gomes ML, Maliska C, Norberg AN (2015) Hemoptysis due to fungus ball after tuberculosis: a series of 21 cases treated with hemostatic radiotherapy. BMC Infect Dis 15(1):546. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-1288-y

Bastin DJ, Arifin AJ, Yaremko BP (2020) External-beam radiation therapy for aspergilloma-associated hemoptysis. Appl Radiat Oncol 9(1):40–42

Shneerson JM, Emerson PA, Phillips RH (1980) Radiotherapy for massive haemoptysis from an aspergilloma. Thorax 35(12):953. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.35.12.953

Sahoo RC, Rau PV, Kumar A, Shivananda PG (1989) Factors causing aspergillus precipitin seronegativity. J Assoc Physicians India 37(10):674

Sahoo RC, Rav PV, Kumar A, Shivananda PG (1990) Effect of antitubercular treatment and radiotherapy on aspergillus precipitin seropositivity in a concomitant case of pulmonary tuberculosis and bronchogenic carcinoma. J Assoc Physicians India 38(12):955–956

Falkson C, Sur R, Pacella J (2002) External beam radiotherapy: a treatment option for massive haemoptysis caused by mycetoma. Clin Oncol 14(3):233–235. https://doi.org/10.1053/clon.2002.0063

Glover S, Holt SG, Newman GH, Kingdon EJ (2007) Radiotherapy for a pulmonary aspergilloma complicating p‑ANCA positive small vessel vasculitis. J Infect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2006.12.007

Samuelian JM, Attia AA, Jensen CA, Monjazeb AM, Blackstock AW (2011) Treatment of hemoptysis associated with aspergilloma using external beam radiotherapy: a case report and literature review. Pract Radiat Oncol 1(4):279–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prro.2011.04.004

Barac A, Kosmidis C, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Salzer HJF (2019) Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis update: a year in review. Med Mycol. https://doi.org/10.1093/mmy/myy070

Denning DW, Pleuvry A, Cole DC (2011) Global burden of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis as a sequel to pulmonary tuberculosis. Bull World Health Organ 89(12):864–872. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.11.089441

Cihoric N, Crowe S, Eychmüller S, Aebersold DM, Ghadjar P (2012) Clinically significant bleeding in incurable cancer patients: effectiveness of hemostatic radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-717X-7-132

Chaw CL, Niblock PG, Chaw CS, Adamson DJ (2014) The role of palliative radiotherapy for haemostasis in unresectable gastric cancer: a single-institution experience. Ecancermedicalscience 8:384. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2014.384

Fuller KK, Ringelberg CS, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC (2013) The fungal pathogen aspergillus fumigatus regulates growth, metabolism, and stress resistance in response to light. mBio. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00142-13

Nourmoradi H, Nikaeen M, Stensvold CR, Mirhendi H (2012) Ultraviolet irradiation: an effective inactivation method of aspergillus spp. in water for the control of waterborne nosocomial aspergillosis. Water Res 46(18):5935–5940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2012.08.015

Salama AM, Ali MI, El-Kirdassy ZHM (1977) A study on fungal radioresistance and sensitivity. Zentralbl Bakteriol Parasitenkd Infektionskr Hyg 132(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-4057(77)80030-0

Nemţanu MR, Braşoveanu M, Karaca G, Erper İ (2014) Inactivation effect of electron beam irradiation on fungal load of naturally contaminated maize seeds. J Sci Food Agric 94(13):2668–2673. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.6607

Nurtjahja K, Dharmaputra OS, Rahayu WP, Syarief R (2017) Gamma irradiation of aspergillus flavus strains associated with indonesian nutmeg (myristica fragrans). Food Sci Biotechnol 26(6):1755–1761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10068-017-0216-x

Sapienza LG, Ning MS, Jhingran A, Lin LL, Leão CR, da Silva BB et al (2019) Short-course palliative radiation therapy leads to excellent bleeding control: a single centre retrospective study. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 14:40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctro.2018.11.007

Strijbos J, van der Linden YM, Vos-Westerman H, van Baardwijk A (2019) Patterns of practice in palliative radiotherapy for bleeding tumours in the Netherlands; a survey study among radiation oncologists. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 15:70–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctro.2019.01.004

Lindberg K, Grozman V, Karlsson K, Lindberg S, Lax I, Wersäll P et al (2021) The HILUS-trial—a prospective nordic multicenter phase 2 study of ultracentral lung tumors treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy. J Thorac Oncol 16(7):1200–1210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2021.03.019

Grozman V, Onjukka E, Wersäll P, Lax I, Tsakonas G, Nyren S et al (2021) Extending hypofractionated stereotactic body radiotherapy to tumours larger than 70cc—effects and side effects. Acta Oncol 60(3):305–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2020.1866776

Ball D, Mai GT, Vinod S, Babington S, Ruben J, Kron T et al (2019) Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus standard radiotherapy in stage 1 non-small-cell lung cancer (TROG 09.02 CHISEL): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 20(4):494–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30896-9

Kim TH, Koo HJ, C‑MM L, S‑BB H, Huh JW, Jo KW et al (2019) Risk factors of severe hemoptysis in patients with fungus ball. J Thorac Dis 11(10):4249–4257. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2019.09.52

Lapa C, Nestle U, Albert NL, Baues C, Beer A, Buck A et al (2021) Value of PET imaging for radiation therapy. Strahlenther Onkol 197(9):1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-021-01812-2

Longhitano A, Alipour R, Khot A, Bajel A, Antippa P, Slavin M et al (2021) The role of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG PET/CT) in assessment of complex invasive fungal disease and opportunistic co-infections in patients with acute leukemia prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant. Transpl Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/tid.13547

Ankrah AO, Creemers-Schild D, de Keizer B, Klein HC, Dierckx RAJO, Kwee TC et al (2021) The added value of [18F]FDG PET/CT in the management of invasive fungal infections. Diagnostics. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11010137

Liu H, Zhang D, Zhang F, Yin J (2016) Immediate and long-term outcomes of endovascular treatment for massive hemoptysis. Int Angiol 35(5):469–476

Cornalba GP, Vella A, Barbosa F, Greco G, Michelozzi C, Sacrini A et al (2013) Bronchial and nonbronchial systemic artery embolization in managing haemoptysis: 31 years of experience. Radiol Med 118(7):1171–1183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11547-012-0866-y

Laursen CB, Davidsen JR, Van Acker L, Salzer HJF, Seidel D, Cornely OA et al (2020) CPAnet registry—an International chronic pulmonary aspergillosis registry. J Fungi (Basel) 6(3):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof6030096

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Bern

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AK analyzed the data, wrote the original draft, and generated tables and figures. DHS helped with screening the literature. DHS, GG, DMA, and OE critically reviewed the manuscript and helped with editing. OE conceived the idea for this work. OE and DMA supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

A. Koch, D.H. Schanne, G. Günther, D.M. Aebersold, and O. Elicin declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

Approval from the institution’s ethics committee was not required for this work. General written informed consent was given by the patient. The patient is not identifiable by the submitted text or images.

Additional information

Availability of data and materials

The article list screened for the systematic review is available from the corresponding author on request.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koch, A., Schanne, D.H., Günther, G. et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for recurrent hemoptysis due to chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: a case report and systematic review of the literature. Strahlenther Onkol 199, 192–200 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-022-02013-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-022-02013-1