Abstract

Background

Several observational studies have suggested a worrying reduction in hospitalisations for acute coronary syndromes in the emergency cardiology department in the last few months all over the world. The aim of the present study is to assess the impact of the current COVID-19 health crisis on admission for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in the cardiology department of a tertiary general hospital in Germany with a COVID-19 ward.

Methods and results

The authors retrieved clinical data evaluating consecutive patients with ACS admitted to their emergency cardiology department. Data from January to June 2020, as well as for a 5-week period corresponding to this yearʼs COVID-19 outbreak in south-west Germany (23rd March–26th April), were analysed and compared to data from equivalent weeks in the previous 2 years. A trend of reduction in admissions for ACS was observed from the beginning of the outbreak in the region at the end of March 2020. This trend continued and even intensified after a fall in COVID-19 cases in the area; the number of ACS patients in April 2020 was 25% and in June 29% lower than in January 2020 (p-value for linear trend <0.001). An even more consistent reduction was observed as compared with the equivalent weeks in the previous 2 years (38% and 30% lower than in 2019 and 2018, respectively; p = 0.009).

Conclusions

The COVID-19 health and social crisis has caused a worrying trend of reduced cardiological admissions for ACS, without evidence of a decrease in its incidence. Understanding and counteracting the causes appears to be crucial to avoiding major long-term consequences for healthcare systems worldwide.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Mehrere Beobachtungsstudien weisen auf einen besorgniserregenden Rückgang der Hospitalisierungen wegen eines akuten Koronarsyndroms (ACS) in kardiologischen Notaufnahmen über die vergangenen Monate hin – und das weltweit. Ziel der vorliegenden Studie war es, die Auswirkungen der gegenwärtigen COVID-19-Gesundheitskrise auf die Aufnahmen wegen ACS in der kardiologischen Abteilung eines deutschen Krankenhauses der Tertiärversorgung mit COVID-19-Station zu untersuchen.

Methoden und Ergebnisse

Ausgewertet wurden klinische Daten konsekutiver Patienten mit ACS, die in der kardiologischen Notaufnahme der Autoren behandelt worden waren. Daten von Januar bis Juni 2020 sowie aus einer 5‑wöchigen Phase, die den diesjährigen COVID-19-Ausbruch in Südwestdeutschland abdeckt (23. März bis 26. April), wurden analysiert und mit Daten aus den entsprechenden Wochen der beiden Vorjahre verglichen. Ein Trend zu reduzierten Aufnahmen wegen ACS zeigte sich ab Beginn des Ausbruchs in der Region Ende März 2020. Dieser Trend hielt an und verstärkte sich nach einem Abfall der COVID-19-Fälle in der Region sogar; die Zahl der Patienten mit ACS war im April 2020 25% und im Juni 29 % niedriger als im Januar 2020 (p-Wert für linearen Trend <0,001). Eine noch beständigere Reduktion zeigte sich im Vergleich mit den entsprechenden Wochen in den beiden Vorjahren (38 % und 30 % niedriger als 2019 bzw. 2018; p = 0,009).

Schlussfolgerungen

Die gesundheitliche und gesellschaftliche Krise durch COVID-19 hat zu einem besorgniserregenden Rückgang kardiologischer Aufnahmen wegen ACS geführt, ohne dass es Hinweise auf eine reduzierte Inzidenz geben würde. Es erscheint von wesentlicher Bedeutung, die Ursachen zu verstehen und ihnen entgegenzuwirken, um schwerwiegende Langzeitfolgen für Gesundheitssysteme weltweit zu vermeiden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ongoing Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2), has been associated with an increased death toll worldwide. Due to high infectiousness and initial reports of severe morbidity and mortality associated with the disease, virtually every country in the world, including Germany, has taken serious preventive measures, including home isolations, limitations and monitoring of transportation and workplaces [1].

A relevant part of the healthcare system has also been redirected in management of COVID-19 cases. As a result of this and as a measure to avoid in-hospital contagion, elective non-urgent procedures and hospital admissions were drastically reduced and postponed in all medical specialties, while the management of urgent cases proceeded unchanged [2]. However, recent publications show that urgent and potentially life-saving procedures and admissions have also been inadvertently reduced, the reasons for such troublesome findings being likely multifactorial and not yet studied in depth [3,4,5,6,7,8].

Furthermore, several observational studies have suggested a worrisome reduction in hospitalisations for acute coronary syndromes in the emergency cardiology department in the last few months all over the world [3, 6]. Especially in older individuals with various co-morbidities in which symptoms of acute coronary events are usually less specific, a delay in diagnosis and lack of appropriate treatment can lead to rapid deterioration and death as well as chronic, long-lasting disabilities [9, 10].

In accordance with the instructions given, the authorsʼ hospital changed its structure as a tertiary hospital and dedicated part of the intensive care unit as well as medical wards to the treatment of severe and mild COVID-19 cases and reduced all non-urgent procedures. The aim of the present study is to assess the impact of the current COVID-19 health crisis on admissions for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in the emergency cardiology department of a tertiary general hospital in Germany with a COVID-19 ward.

Methods

The design of the present study is an observational, retrospective analysis of urgent visits and admissions to the authorsʼ emergency cardiology department with ACS during the COVID-19 crisis as compared to equivalent periods in the previous years. Clinical data evaluating consecutive patients with ACS admitted to the cardiological department of Municipal Hospital of Karlsruhe, Germany, were retrieved. The data were collected for the period between January 1st and June 30th 2020 and equivalent months in the preceding 2 years, including a 5-week period corresponding to this year’s COVID-19 outbreak in south-west Germany (23rd March–26th April).

Measurements

Data were extracted from the hospital’s database on all visits to the authorsʼ emergency cardiology department during the aforementioned period according to initial and discharge diagnosis. For the present study, only patients with confirmed ACS at discharge were considered.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as absolute numbers or percentages and compared by chi-squared test adjusted with the Bonferroni method. Linear-trend models were estimated to evaluate differences in admissions during the studied period of time in three different years (2018, 2019 and 2020) and throughout the same year. All tests were two-sided, and a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

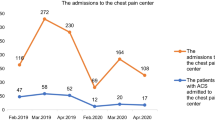

During the first 6 months of 2020, there were a total of 270 admissions for ACS to the authorsʼ emergency cardiology department. In comparison, in the same period in 2019 and in 2018, admissions for ACS were 353 and 326, respectively, representing a decline of 24% and 19%. A trend of reduction in admissions for ACS was observed from the beginning of the outbreak in the region at the end of March 2020; in particular, admissions for ACS were 25% lower in April compared to January 2020 (p-value for linear trend <0.001). The absolute number of admissions in March and April this year was at its absolute lowest compared to any other month in the previous 3 years (Fig. 1). This trend continued and even intensified after a reduction of COVID-19 cases in the area: in May 2020, the number of patients with ACS was 19% and in June 29% lower than in January 2020 (p-value for linear trend <0.001). A similar trend was not observed in previous years (Fig. 1).

Considering the 5‑week period of the COVID-19 outbreak in south-west Germany, an even more significant and consistent reduction was observed compared with equivalent periods in the previous 2 years (38% and 30% lower than in 2019 and 2018, respectively; p-value = 0.009) (Fig. 2).

Finally, the total number of coronary angiographies and percutaneous coronary interventions performed in the authorsʼ cardiology department was 41% and 42%, respectively, lower than in 2019 (p-value <0.001 for both years) and 31% and 42%, respectively, than in 2018 (p-value <0.001 for both years) (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The main finding of the present study is the dramatic reduction in the number of hospitalizations for ACS at the authorsʼ hospital during and after this year’s COVID-19 outbreak. This phenomenon started as COVID-19 cases increased and continued with increased significance even as the outbreak faded.

The authorsʼ hospital is a tertiary medical facility which provides advanced medical care for the population of the city of Karlsruhe and its sub-urban area (ca. 450,000 people). The cardiology department in this study includes a 12-bed intensive care unit, a 12-bed cardiac care unit and a 22-bed sub-intensive care unit.

The first case in the region was reported on the 28th of February, while the outbreak peaked at the end of the month [11]. The German government enforced quarantine measures including limitations on public and working activities, as well state school closure on 24th of March [12]. In compliance with the enforced measures, the authors postponed all elective, deferrable activities on the 28th of March until the 26th of April, and a significant part of their resources was shifted to the management of severe and mild COVID-19 cases.

An initial evaluation of visits to their emergency department included vital parameters (i.e. blood pressure, temperature, oxygen saturation), as well as a standard 12-channel electrocardiogram and a brief medical history. Patients with signs and symptoms suspicious for respiratory infectious diseases underwent imaging screening of the lung (i.e. radiography or computed tomography scan), as well as swab testing for SARS-COV‑2, and remained isolated in the authorsʼ COVID-19 area until test results were available. In the case of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) with suspected COVID-19, the protocol dictates immediate cardiac catheterization in a dedicated catheter laboratory with all protective measures in place, including proper negative pressure room ventilation and personal protective devices such as FFP‑3 face masks, in accordance with guidelines of the German Society of Cardiology [13]. With regard to door-to-balloon intervals, a possible delay in care delivery has been observed in the current literature [5], while other studies showed no significant delay in ACS management throughout the STEMI Network in Germany, and as the authorsʼ managing protocols did not change during the outbreak, they do not expect a significant delay to have taken place in their hospital [2].

The total number of cardiac catheterisations and percutaneous coronary interventions with stenting was also significantly reduced. This could be partially due to a combination of reduced hospitalisations for acute cardiological diseases and of lack of elective procedures in the authorsʼ cardiological department during the outbreak.

Although a link between viral infections and, more specifically, between coronaviruses and acute cardiovascular events has been known and well established [13,14,15], many recent studies, in agreement with the present findings, point to a significant reduction in hospitalisations for such events [3,4,5,6,7]. A large multi-centre study in Italy recorded a reduction of up to 59% in admissions for ACS during the peak of the outbreak in Italy compared to equivalent periods in the previous years [6]. Similar observations were reported in Spain, the United States, Austria and China [4, 7, 16, 17].

Many studies have been conducted to investigate this phenomenon [6, 13, 18]. First, the fear of contagion at the hospital may have discouraged access to emergency medical facilities. The fact that the reduction in admissions at the authorsʼ facilities continued, and even became more consistent as the number of COVID-19 cases dropped and the government loosened quarantine measures, suggests that this psychological element may represent an important factor. This may imply a troublesome increase in elapsed, non-treated ACS in the general population that did not seek medical attention. This appears to also apply to non-cardiological acute diseases. In concordance with this hypothesis, Kristoffersen et al. demonstrated not only that the admissions for acute stroke in a Norwegian hospital decreased during the COVID-19 outbreak, but also the severity of the disease was more significant than in previous years, suggesting either that patients with mild forms of the disease did not seek medical attention at all or that they waited until worsening of the symptoms before seeking medical help [8]. The extent of such non-treated cases and their effect on public health will become apparent in the near future, when data on general mortality during the COVID-19 outbreak and on rates of post-myocardial infarction heart failure and arrhythmias become available [9, 10]. A second hypothesis is linked to the fact that the authors cannot completely exclude the possibility that a true reduction in the incidence of ACS as a potential beneficial result of low mental and physical stress during the quarantine might have partially contributed to the lower number of admissions to the emergency cardiology department in question [19]. Although data on the current COVID-19 outbreaks are not yet available, Wang et al. showed how people undergoing quarantine during the H1N1 2009 outbreak in China did not suffer from more stressful experiences than people not affected by quarantine measures [20]. On the other hand, arterial and venous thromboembolic events and cases of disseminated intravascular dissemination have been described in the recent literature, as COVID-19 is associated with an inflammatory status characterised by coagulation activation and endothelial dysfunction [21,22,23].

Finally, the fact that the emergency medical system was focused on COVID-19 and healthcare resources were reallocated to manage the pandemic may have largely contributed to the reduction in emergency cardiological admissions. This might have induced an attitude towards deferral of less urgent cases, at both the patient and the healthcare system levels. Other studies have also pointed in this direction: De Rosa et al., for example, showed how in Italy, in spite of a significant overall reduction in hospitalisations for ACS, the reduction for STEMI was less striking than that for NSTEMI [6]. Of note, this may also be true for the in-hospital management of ACS patients. In fact, at the authorsʼ hospital the number of total catheterisations and percutaneous coronary interventions in the catheterisation laboratory dropped significantly, showing a tendency to postpone non-urgent, deferrable cases during the outbreak.

Despite a reallocation of resources and beds in the cardiac intensive care unit in this study to address the COVID-19 outbreak, the reduction in admissions for ACS does not seem to be linked to the lack of non-COVID-19 beds, as intensive care beds in the non-COVID-19 area remained continuously available.

Limitations

The study has a number of limitations given that this is a retrospective analysis of the admissions to a hospital and, therefore, no data are available on the clinical characteristics or implications of those patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the COVID-19 health and social crisis has caused a worrisome trend of reduced cardiological admissions for ACS, without evidence of a decrease in its incidence. Understanding and counteracting the causes for this appears to be crucial in order to avoid major and long-standing consequences for healthcare systems worldwide.

References

Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, Ren R, Leung KSM, Lau EHY, Wong JY, Xing X, Xiang N, Wu Y, Li C, Chen Q, Li D, Liu T, Zhao J, Liu M, Tu W, Chen C, Jin L, Yang R, Wang Q, Zhou S, Wang R, Liu H, Luo Y, Liu Y, Shao G, Li H, Tao Z, Yang Y, Deng Z, Liu B, Ma Z, Zhang Y, Shi G, Lam TTY, Wu JT, Gao GF, Cowling BJ (2020) Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected. Pneumonia 382(13):1199–1207. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001316

Scholz KH, Lengenfelder B, Thilo C, Jeron A, Stefanow S, Janssens U, Bauersachs J, Schulze PC, Winter KD, Schröder J, Vom Dahl J, von Beckerath N, Seidl K, Friede T (2020) Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on regional STEMI care in Germany. Clin Res Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-020-01703-z

Tsioufis K, Chrysohoou C, Kariori M, Leontsinis I, Dalakouras I, Papanikolaou A, Charalambus G, Sambatakou H, Siasos G, Panagiotakos D, Tousoulis D (2020) The mystery of “missing” visits in an emergency cardiology department, in the era of COVID-19.; a time-series analysis in a tertiary Greek general hospital. Clin Res Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-020-01682-1

Garcia S, Albaghdadi MS, Meraj PM, Schmidt C, Garberich R, Jaffer FA, Dixon S, Rade JJ, Tannenbaum M, Chambers J, Huang PP, Henry TD (2020) Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 75(22):2871–2872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011

Tam CF, Cheung KS, Lam S, Wong A, Yung A, Sze M, Lam YM, Chan C, Tsang TC, Tsui M, Tse HF, Siu CW (2020) Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction care in Hong Kong, China. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 13(4):e6631. https://doi.org/10.1161/circoutcomes.120.006631

De Rosa S, Spaccarotella C, Basso C, Calabrò MP, Curcio A, Filardi PP, Mancone M, Mercuro G, Muscoli S, Nodari S, Pedrinelli R, Sinagra G, Indolfi C (2020) Reduction of hospitalizations for myocardial infarction in Italy in the COVID-19 era. Eur Heart J 41(22):2083–2088. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa409

Metzler B, Siostrzonek P, Binder RK, Bauer A, Reinstadler SJ (2020) Decline of acute coronary syndrome admissions in Austria since the outbreak of COVID-19: the pandemic response causes cardiac collateral damage. Eur Heart J 41(19):1852–1853. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa314

Kristoffersen ES, Jahr SH, Thommessen B, Rønning OM (2020) Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on stroke admission rates in a Norwegian population. Acta Neurol Scand. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.13307

Scholz KH, Maier SKG, Maier LS, Lengenfelder B, Jacobshagen C, Jung J, Fleischmann C, Werner GS, Olbrich HG, Ott R, Mudra H, Seidl K, Schulze PC, Weiss C, Haimerl J, Friede T, Meyer T (2018) Impact of treatment delay on mortality in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients presenting with and without haemodynamic instability: results from the German prospective, multicentre FITT-STEMI trial. Eur Heart J 39(13):1065–1074. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy004

Zhang B, Shen DP, Zhou XC, Liu J, Huang RC, Wang YE, Chen AM, Zhu YR, Zhu H (2015) Long-term prognosis of patients with acute non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing different treatment strategies. Chin Med J 128(8):1026–1031. https://doi.org/10.4103/0366-6999.155071

ka-news (2020) Erster Corona-Fall in Karlsruhe bestätigt: Geschäftsreisender aus Nürnberg, Hotline für Bürger aktiv

Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (2020) Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: Chronik der bisherigen Maßnahmen

Böhm M, Frey N, Giannitsis E, Sliwa K, Zeiher AM (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and its implications for cardiovascular care: expert document from the German cardiac society and the world heart federation. Clin Res Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-020-01656-3

Yu CM, Wong RS, Wu EB, Kong SL, Wong J, Yip GW, Soo YO, Chiu ML, Chan YS, Hui D, Lee N, Wu A, Leung CB, Sung JJ (2006) Cardiovascular complications of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Postgrad Med J 82(964):140–144. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2005.037515

Liu PP, Blet A, Smyth D, Li H (2020) The science underlying COVID-19: implications for the cardiovascular system. Circulation 142(1):68–78. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.120.047549

Li B, Yang J, Zhao F, Zhi L, Wang X, Liu L, Bi Z, Zhao Y (2020) Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol 109(5):531–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-020-01626-9

Rodriguez-Leor O, Cid-Alvarez B (2020) ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction care during COVID-19. Losing sight of the forest for the trees. JACC Case Rep 2(10):1625–1627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.011

Katz JN, Sinha SS, Alviar CL, Dudzinski DM, Gage A, Brusca SB, Flanagan MC, Welch T, Geller BJ, Miller PE, Leonardi S, Bohula EA, Price S, Chaudhry SP, Metkus TS, O’Brien CG, Sionis A, Barnett CF, Jentzer JC, Solomon MA, Morrow DA, van Diepen S (2020) COVID-19 and disruptive modifications to cardiac critical care delivery: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol 76(1):72–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.029

Wirtz PH, von Känel R (2017) Psychological stress, inflammation, and coronary heart disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 19(11):111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-017-0919-x

Wang Y, Xu B, Zhao G, Cao R, He X, Fu S (2011) Is quarantine related to immediate negative psychological consequences during the 2009 H1N1 epidemic? Gen Hosp Psychiatry 33(1):75–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.11.001

Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, Cecconi M, Ferrazzi P, Sebastian T, Kucher N, Studt JD, Sacco C, Alexia B, Sandri MT, Barco S (2020) Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res 191:9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024

Klok FA, Kruip M, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers D, Kant KM, Kaptein FHJ, van Paassen J, Stals MAM, Huisman MV, Endeman H (2020) Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res 191:145–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013

Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, Mehra MR, Schuepbach RA, Ruschitzka F, Moch H (2020) Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet 395(10234):1417–1418. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30937-5

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

G. Vacanti, P. Bramlage, G. Schymik,C. Schmitt, A. Luik, P. Swojanowsky and P. Tzamalis declare that they have no competing interests.

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies performed were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case.

Additional information

Availability of data and material

Upon request

Contributors

Study conception, design, analysis and interpretation: PT, drafting of the manuscript: GV, PB and PT. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vacanti, G., Bramlage, P., Schymik, G. et al. Reduced rate of admissions for acute coronary syndromes during the COVID-19 pandemic: an observational analysis from a tertiary hospital in Germany. Herz 45, 663–667 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-020-04991-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-020-04991-3

Keywords

- Myocardial infarction

- Percutaneous coronary intervention

- Acute coronary events

- SARS-CoV‑2

- Coronary angiography