Abstract

About 20–25% of all ischemic strokes are of cardioembolic etiology, with atrial fibrillation and heart failure as the most common underlying pathologies. Diagnostic work-up by noninvasive cardiac imaging is essential since it may lead to changes in therapy, e.g., in—but not exclusively—secondary stroke prevention. Echocardiography remains the cornerstone of cardiac imaging after ischemic stroke, with the combination of transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography as gold standard thanks to their high sensitivity for many common pathologies. Transesophageal echocardiography should be considered as the initial diagnostic tool when a cardioembolic source of stroke is suspected. However, to date, there is no proven benefit of transesophageal echocardiography-related therapy changes on the main outcomes after ischemic stroke. Based on the currently available data, cardiac computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging should be regarded as complementary methods to echocardiography, providing additional information in specific situations; however, they cannot be recommended as first-line modalities.

Zusammenfassung

Etwa 20–25 % der ischämischen Schlaganfälle sind kardioembolischer Genese mit Vorhofflimmern und Herzinsuffizienz als den häufigsten Ursachen. Die diagnostische Aufarbeitung mittels kardialer Bildgebung ist unerlässlich, da sie zu therapeutischen Veränderungen führen kann, beispielsweise, aber nicht ausschließlich, hinsichtlich der sekundären Schlaganfallprävention. Die Echokardiographie bleibt die Basis der kardialen Bildgebung nach einem ischämischen Schlaganfall mit der Kombination aus transthorakaler und transösophagealer Echokardiographie als Goldstandard aufgrund der hohen Sensitivität für die häufigsten pathologischen Veränderungen. Bei einem klinischen Verdacht auf einen kardioembolischen Schlaganfall sollte die transösophageale Echokardiographie als initiale Untersuchung erwogen werden. Allerdings wurde bisher nicht anhand einer Studie nachgewiesen, dass die aufgrund der transösophagealen Echokardiographie geänderten therapeutischen Maßnahmen für die Hauptendpunkte nach Schlaganfall von Vorteil seien. Auf der Grundlage der derzeit verfügbaren Studien sollten die kardiale Computertomographie und die kardiale Magnetresonanztomographie als ergänzende Methoden zur Echokardiographie betrachtet werden, die in bestimmten Situationen zusätzliche Informationen liefern können, aber nicht als Standarddiagnostik dienen sollten.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In Europe, about 87% of all strokes are considered to be ischemic and 13% are hemorrhagic strokes [1]. According to the TOAST (Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Ischemic Stroke) criteria [2], ischemic stroke can be divided into five categories based on the assumed etiology:

-

Large-artery atherosclerosis,

-

Cardioembolism,

-

Small-vessel occlusion,

-

Stroke of other determined etiology,

-

Stroke of undetermined (cryptogenic) etiology.

Cardioembolism accounts for about 20–25% of all ischemic strokes [3]. However, the pathogenesis of stroke remains unexplained in up to 30% of all patients (so-called cryptogenic stroke). This may be due to competing causes of stroke (i.e., ipsilateral carotid stenosis and atrial fibrillation [AF]), insufficient diagnostic work-up, or standard diagnostic work-up without relevant pathological findings. Based on long-term electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring, it is assumed that a significant proportion of suspected cryptogenic strokes might have been of cardioembolic origin [4,5,6]. Compared with non-cardioembolic strokes, cardioembolic strokes are more severe and are associated with increased mortality and disability and a high recurrence rate [7, 8]. A thorough work-up after stroke is important since it might lead to changes in secondary stroke prevention [9].

For cardiac sources of embolism, a distinction was made between high-risk and low-risk cardiovascular sources (Table 1). The most common causes of cardioembolism are AF, left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and LV thrombus, endocarditis, prosthetic valves, and patent foramen ovale (PFO), with AF accounting for the majority of cases [10]. Although screening for AF by ECG, monitoring during stroke unit stay, and, if suspicion for AF is high, additional longer-term ECG monitoring have become routine, sequential cardiac imaging after ischemic stroke is less well established [11]. This is usually achieved with transthoracic (TTE) or transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). Transthoracic echocardiography has been increasingly performed as part of stroke work-up in the past few years, whereas TEE is used infrequently [12,13,14,15]. In recent years, some studies have assessed the potential benefits of cardiac computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) regarding the evaluation of sources of cardioembolism.

The objective of this work is to provide an overview of the available clinical data on cardiac imaging after acute ischemic stroke including cardiac CT and MRI. Imaging results may vary significantly depending on the settings, machines, and protocols used for imaging, but details on technical aspects are beyond the scope of this review. The general advantages and disadvantages of all four imaging modalities are summarized in Fig. 1.

Cardiac imaging after acute ischemic stroke

Transthoracic vs. transesophageal echocardiography

Both TTE and TEE have specific advantages and disadvantages. Transthoracic echocardiography is well suited to imaging of anterior cardiac structures including the ventricles, while posterior structures such as the left atrium (LA) and the left atrial appendage (LAA) are less well captured because of the greater distance to the probe. Image quality may be limited owing to specific patient characteristics (e.g., chest wall abnormalities, lung disease, or obesity). On the other hand, TEE has hardly any acoustic limitations thanks to the proximity of the imaging probe to the LA and thoracic aorta. Therefore, it is intended for diagnosis of abnormalities not detected on TTE (Table 2). Despite its semi-invasive nature, TEE is considered to be a safe procedure and serious complications such as gastroesophageal injuries, major bleeding, or sustained dysrhythmias are rare [16]. Nevertheless, it is often necessary to use mild sedation and certain conditions constitute a contraindication for TEE (Table 3).

Current guidelines do not provide clear recommendations regarding the use of echocardiography for stroke patients. Whereas the guideline on acute stroke management issued by the American Heart Association [17] does not mention echocardiography at all, the European Stroke Organization guideline [18] recommends echocardiography in selected patients (Class III, Level B recommendation). However, the European Stroke Organization guideline does not provide any recommendation as to the choice of TTE or TEE. Current echocardiography guidelines recommend routine use of TTE as a screening tool for potential cardiac sources of embolism [19, 20]. Transesophageal echocardiography might also be considered as an initial or supplemental test in specific patients, e.g., in cases of suspected endocarditis if TTE is normal. Transesophageal echocardiography is not recommended if potential results will not change the therapeutic decisions. Owing to the lack of clear recommendations, the diagnostic use of TEE and TTE varies considerably between stroke centers [21].

In a predominantly prospective, two-center study of 824 ischemic stroke patients, 95% of all patients with cardiac pathologies identified by TEE had an abnormal TTE and/or AF [22]. Furthermore, TEE did not result in additional findings that changed the therapeutic regimen to oral anticoagulation (OAC) in patients with normal TTE and sinus rhythm. In another prospective nonrandomized single-center study of 231 patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) and no indication for OAC after routine work-up (not including prolonged rhythm monitoring), de Bruijn et al. [23] found a thrombus in 18% of the patients undergoing TEE compared with 2% of patients undergoing TTE. Almost all of these thrombi were located in the LAA. Harloff et al. [24] evaluated the additional benefit of TEE compared with routine work-up in a prospective, single-center study of 503 ischemic stroke patients. The TEE findings led to OAC administration in 8% of 212 patients with as-yet cryptogenic ischemic stroke. However, there was only a single case with an evidence-based indication for OAC (LA thrombus), while in all other cases the indication for OAC was debatable (e.g., LA spontaneous echo contrast [SEC] or aortic thrombi). In a retrospective analysis of 441 unselected patients with ischemic stroke or TIA, TEE was superior to TTE in identifying potential sources of cardioembolism [25]. The difference was mainly due to detection of LAA thrombi, aortic thrombi, and PFO. The additional diagnostic yield of TEE decreased significantly if individuals with known AF or cardiac disease (e.g., congestive heart failure or coronary artery disease) were excluded [25]. Nevertheless, a retrospective analysis identified a non-AF-related major source of embolism in 3.8% of 185 AF patients with acute ischemic stroke undergoing TEE and/or TTE. In addition, 32% of 75 AF patients undergoing TEE had aortic plaques [26].

Echocardiography vs. magnetic resonance imaging

In a prospective single-center study of 103 ischemic stroke patients, cardiac MRI identified a potential stroke etiology in an additional 6.1% of patients with a cryptogenic stroke according to routine work-up including TEE and in most cases TTE [27]. Four of these five patients had wall motion abnormalities in three or more segments, one was diagnosed with an aortic plaque of ≥4 mm that was missed on echocardiography. However, cardiac MRI failed to reveal a TEE-detected high-risk source of embolism in five cases. In four of these five cases, cardiac MRI was terminated prematurely on behalf of the patient or the urgent need to examine another stroke patient. Of note, late gadolinium enhancement—consistent with previous myocardial infarction—was found in 13 (14.6%) out of 89 stroke patients completing cardiac MRI, of whom only two had known coronary artery disease. The detection of subclinical past myocardial infarction with the help of cardiac MRI in stroke patients is in line with findings from prior studies [28, 29].

Baher et al. [28] evaluated the additional benefit of cardiac MRI in 85 ischemic stroke patients after routine work-up including TTE, but not TEE. Cardiac MRI identified a potential source of embolism in 26% of cases, which were classified as a cryptogenic stroke after routine work-up. Three of these patients had an evident embolic source (LV thrombus [n = 2] or complex aortic thrombus). In the remaining three patients, cardiac MRI detected a low-risk embolic source (atrial septal aneurysm [ASA] [n = 2] or PFO/ASA).

Echocardiography vs. computed tomography

Boussel et al. [30] evaluated the role of cardiac CT in a small cohort of patients with cryptogenic stroke. Compared with TEE as reference, CT had a sensitivity of 72% and a specificity of 95% for correct identification of the embolic source. All cases of aortic atheroma diagnosed with TEE were also detected by using CT. Sipola et al. [29] investigated whether combined examination of the heart, aorta, and brain-supplying arteries with CT could improve the diagnosis of stroke etiology compared with standard diagnostics including TTE and TEE in 140 patients with suspected cardioembolic stroke or TIA mainly based on brain imaging findings. The authors conclude that the combined use of CT and TTE/TEE was more sensitive than TTE/TEE alone for detecting at least one high-risk finding. This was mainly due to the detection of previous myocardial infarctions, which were considered as a high-risk embolic source in this study. Computed tomography further identified one additional LV thrombus, but CT was not suitable for diagnosing small LA thrombi. In an earlier prospective single-center study of 137 stroke patients with a high cardiovascular risk profile, cardiac CT was of similar diagnostic value to TEE regarding the identification of high-risk sources of embolism [31]. However, CT failed to detect many low-risk sources of embolism such as PFO/ASA. Furthermore, CT did not yield any additional findings to TEE.

Cardiac imaging for specific sources of cardioembolism

As indicated earlier, all four imaging modalities differ significantly in terms of their diagnostic performance regarding specific sources of cardioembolism (Table 2).

Left ventricular thrombus and cardiomyopathy

The development of an LV thrombus is a severe complication of myocardial infarction. Its incidence has decreased significantly with the rise of modern reperfusion measures, but LV thrombus may still occur in up to 8% of patients after ST-elevation myocardial infarction [32, 33]. Left ventricular thrombi are associated with an increased risk for ischemic stroke, which can be reduced by the use of OAC [34, 35].

Cardiac MRI has been shown to have higher sensitivity and specificity for the detection of LV thrombi when compared with TTE and TEE and is considered the gold standard in this setting [36,37,38]. Nevertheless, TTE is most frequently used for the detection of LV thrombus and may serve as an initial screening test [32]. The diagnostic accuracy of TTE can be improved by the application of endocardial border definition contrast agent resulting in a sensitivity of 61% compared with cardiac MRI [38]. Since many LV thrombi are located in the region of the LV apex, TEE is not superior to TTE for the detection of LV thrombi [23, 36]. If there is high suspicion for an LV thrombus despite a normal finding on TTE, cardiac MRI should be performed for further clarification [39]. If cardiac MRI is not available, CT might also be an option [29, 30, 40, 41].

While LV thrombi are most commonly seen in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, other cardiomyopathies are also associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke. Dilated cardiomyopathy is characterized by a reduction in LV ejection fraction and dilatation of the ventricle, and therefore initial screening can be done by TTE. For further refinement of the etiology, cardiac MRI can be helpful [42]. Reports on the incidence of thromboembolism in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy showed varying results with incidence ranging from 1.7 to 3.5 events per 100 patient-years [43,44,45]. Another rare cardiomyopathy that may cause cardioembolic stroke is LV non-compaction [46, 47]. It is characterized by multiple prominent ventricular trabeculations with intertrabecular spaces communicating within the ventricular cavity [46]. Transthoracic echocardiography is the initial imaging modality of choice, and application of contrast agent should be considered as it enhances the endocardial border definition unmasking the deep intertrabecular recesses [20, 47]. Again, cardiac MRI might be performed to confirm the diagnosis and exclude LV thrombi.

Left atrial (appendage) thrombus

The LA and the LAA are the most common sites for intracardiac thrombi and characteristics of both structures have been linked to incident AF and stroke recurrence [48,49,50,51,52]. Left atrial dilation is associated with incident AF and other cardiovascular diseases [50]. Furthermore, the risk of stroke for individuals in sinus rhythm increases along with LA dimensions [53]. In stroke patients with known AF, LA enlargement is a predictor of a higher rate of recurrent stroke or systemic embolism [49]. Before an LAA thrombus manifests, SEC and a reduced LAA flow peak velocity can often be detected [54]. The presence of SEC in patients with AF after stroke has been associated with a poor prognosis and is related to poor long-term functional outcome [48].

Since the sensitivity of TTE for the detection of LA/LAA thrombi is low, TEE is considered the standard diagnostic tool [23]. On the other hand, LA/LAA thrombus is very infrequently detected in the presence of sinus rhythm [22, 55]. Agmon et al. [55] found that patients with LA thrombus and sinus rhythm constitute a high-risk group characterized by structural cardiac abnormalities or previous AF. In a meta-analysis by Romero et al. [56], the mean sensitivity and specificity of cardiac CT was 96% and 92% compared with TEE, respectively. In a further subanalysis of seven mostly prospective, single-center studies in which delayed imaging CT was performed, sensitivity and specificity further increased to 100% and 99%, respectively. In addition to its noninvasive character, CT also offers a superior visualization of the anatomy of the LAA [57]. Although it has not been investigated as extensively as CT, cardiac MRI is also an alternative for the evaluation of the LAA [58]. In a recent retrospective register analysis of patients undergoing pulmonary vein isolation, all thrombi detected by TEE were also found with the use of delayed enhancement cardiac MRI [59]. Ohyama et al. [60] found that in 50 patients with non-valvular AF, all thrombi were successfully identified by cardiac MRI with TEE as the reference standard; but artifacts might result in false-positive findings.

Patent foramen ovale

A PFO results from the incomplete fusion of the septum primum and the septum secundum in the fossa ovalis [61]. This is a common phenomenon in the general population with a prevalence of about 25% and represents a potential mechanism for paradoxical embolisms via a right-to-left shunt [61, 62]. It is observed significantly more frequently in patients with cryptogenic stroke than in patients with clarified stroke etiology and is associated with an increased risk of stroke recurrence in the presence of an ASA [61, 63]. Recently published controlled trials of patients with cryptogenic stroke showed a significant reduction of stroke recurrence rate by interventional PFO closure compared with standard drug therapy [64, 65]. Based on the currently available data, an interventional PFO closure may be considered in selected patients with cryptogenic stroke, aged ≤60 years, with moderate-to-high atrial shunt volume [66].

The gold standard for the diagnosis of PFO is TEE with a so-called bubble test [67]. An agitated air–saline solution is injected intravenously and a possible bubble transition from the right to the left atrium is examined. If possible, this procedure is repeated while the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver. Screening for a shunt at atrial level can also be performed by TTE with a bubble test, which reliably detects large right-to-left shunts, while smaller shunts are frequently missed [67]. In order to establish the exact anatomy and the precise shunt volume, a TEE examination is necessary. Computed tomography is inferior to TEE with regard to the detection of interatrial septum abnormalities [30, 31, 68]. Kim et al. [68] retrospectively compared the diagnostic performance of TEE and CT in 152 stroke patients. The authors were able to visualize a left-to-right shunt in 21 of the 26 patients in whom a PFO was detected with TEE (sensitivity and specificity of CT were 73% and 98%, respectively). Cardiac MRI currently has no relevance in the diagnosis of a PFO. In a prospective study of patients with cryptogenic stroke, cardiac MRI detected only three out of 31 patients with PFO according to TEE [27]. The superiority of TEE in this regard is in line with data from previous studies, although cardiac MRI performed comparatively better [69, 70].

Valvular disease

Infective endocarditis (IE) constitutes a severe disease and one of its major complications is septic embolism [71]. Cerebral lesions can be found in up to 80% of patients with left-sided IE, with many episodes being silent and only detectable on cranial imaging [72,73,74]. The risk of embolism steadily declines after initiation of appropriate antimicrobial therapy [75]. According to current guidelines, TTE is recommended as the first-line imaging modality in cases of suspected IE [71]. However, TEE is superior to TTE in diagnosing IE especially in the case of small vegetations, poor image quality, or prosthetic heart valves [76]. Therefore, if there is persistent clinical suspicion, a TEE examination should be performed despite a normal TTE and repeated if deemed necessary [71]. Furthermore, TEE is obligatory in patients with an abnormal TTE in order to exclude potential complications such as a paravalvular abscess [71]. Besides securing the diagnosis, echocardiography can also aid in the prediction of embolic risk, e.g., vegetation size of >10 mm and mobility are the strongest independent risk factors for embolism [77, 78].

Computed tomography has a good diagnostic accuracy for IE lesions compared with TEE, but small vegetations and leaflet perforations may be missed [79, 80]. On the other hand, CT is often superior to TEE for the assessment of the perivalvular extent of the disease [79, 80]. Furthermore, it can be helpful in cases of prosthetic valve IE, in which acoustic shadows might decrease the sensitivity of TEE [81]. Owing to its lower spatial resolution, MRI does not play a role in the diagnosis of IE.

Besides IE, prosthetic valves might also lead to cerebral embolism as a result of thrombus formation, which is often caused by an inadequate anticoagulation [82]. The incidence rate of mechanical valve thrombosis in patients using anticoagulation is about 0.4 per 100 patient-years, whereas it is believed to be lower in patients with bioprosthesis [83, 84]. The thrombus might cause obstruction of the valve, which can be detected on TTE using the Doppler technique [85]. If suspicion of thrombus formation is high, TEE should be performed for further evaluation. If TEE remains inconclusive, it should be followed by CT for assessment of potential thrombus or pannus [85].

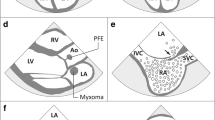

Cardiac tumors

Primary cardiac tumors are rare and usually benign [86]. Myxomas are the most common primary cardiac tumors and are usually located in the LA. Cerebral embolism occurs in about 30% of cases [87]. Papillary fibroelastomas are by far the most frequent valve-associated tumors and together with myxomas account for the majority of primary cardiac tumors in adults [20, 88, 89]. They are often first diagnosed after thromboembolic stroke [90]. Echocardiography is usually sufficient for the diagnosis of intracardiac tumors with TEE, providing higher sensitivity and spatial resolution [91]. Cardiac CT and MRI generate excellent high-resolution images and can provide important additional information on the extent of the tumor and vascularization. Cardiac MRI is preferred over CT because specific MRI sequences can aid in tissue characterization and in the differential diagnosis including signs of malignancy [89].

Conclusion

Echocardiography remains the cornerstone of cardiac imaging after acute ischemic stroke. Based on the currently available literature, TTE and TEE should be considered as complementary methods. Transthoracic echocardiography provides comprehensive information on cardiac structure and function and should the first method of choice in most patients. However, TEE might offer additional information especially in patients with a suspected cardioembolic source of stroke and therefore should be considered as the initial examination in these patients. Cardiac CT or MRI may be taken into account as an alternative if TEE is not possible/not available in a timely manner. Currently, the evidence on the effect of cardiac imaging-based changes in clinical management on prognosis after stroke remains scarce, but will hopefully accumulate in the future.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- ASA:

-

Atrial septal aneurysm

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- IE:

-

Infective endocarditis

- LA:

-

Left atrial/left atrium

- LAA:

-

Left atrial appendage

- LV:

-

Left ventricular

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- OAC:

-

Oral anticoagulation

- PFO:

-

Patent foramen ovale

- TEE:

-

Transesophageal echocardiography

- TIA:

-

Transient ischemic attack

- TTE:

-

Transthoracic echocardiography

References

Grysiewicz RA, Thomas K, Pandey DK (2008) Epidemiology of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke: incidence, prevalence, mortality, and risk factors. Neurol Clin 26:871–895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2008.07.003

Adams HP et al (1993) Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke 24:35–41

Kolominsky-Rabas PL, la (2001) Epidemiology of ischemic stroke subtypes according to TOAST criteria: incidence, recurrence, and long-term survival in ischemic stroke subtypes: a population-based study. Stroke 32:2735–2740

Hart RG et al (2014) Embolic strokes of undetermined source: the case for a new clinical construct. Lancet Neurol 13:429–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70310-7

Sanna T et al (2014) Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 370:2478–2486. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1313600

Li L et al (2015) Incidence, outcome, risk factors, and long-term prognosis of cryptogenic transient ischaemic attack and ischaemic stroke: a population-based study. Lancet Neurol 14:903–913. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(15)00132-5

Marini C et al (2005) Contribution of atrial fibrillation to incidence and outcome of ischemic stroke: results from a population-based study. Stroke 36:1115–1119. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000166053.83476.4a

Yasaka M et al (2018) Recurrent stroke and bleeding events after acute cardioembolic stroke-analysis using Japanese healthcare database from acute-care institutions. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 27:1012–1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.11.002

Kernan WN et al (2014) Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 45:2160–2236. https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0000000000000024

Kim Y et al (2016) Novel echocardiographic indicator for potential cardioembolic stroke. Eur J Neurol 23:613–620. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12909

Haeusler KG et al (2018) Expert opinion paper on atrial fibrillation detection after ischemic stroke. Clin Res Cardiol 107:871–880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-018-1256-9

Ng VT et al (2016) Temporal trends in the use of investigations after stroke or transient ischemic attack. Med Care 54:430–434. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000499

Grau AJ et al (2010) Quality monitoring of acute stroke care in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, 2001–2006. Stroke 41:1495–1500. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.110.582239

Uchino K et al (2004) Ischemic stroke subtypes among Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites: the BASIC Project. Baillieres Clin Neurol 63:574–576

Giruparajah M et al (2015) Global survey of the diagnostic evaluation and management of cryptogenic ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke 10:1031–1036. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijs.12509

Hilberath JN et al (2010) Safety of transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 23:1115–1127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2010.08.013 (quiz 1220–1111)

Powers WJ et al (2018) 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute Ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 49:e46–e110. https://doi.org/10.1161/str.0000000000000158

European Stroke Organisation (2008) Guidelines for management of ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack 2008. Cerebrovasc Dis 25:457–507. https://doi.org/10.1159/000131083

Saric M et al (2016) Guidelines for the use of echocardiography in the evaluation of a cardiac source of embolism. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 29:1–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2015.09.011

Pepi M et al (2010) Recommendations for echocardiography use in the diagnosis and management of cardiac sources of embolism: European Association of Echocardiography (EAE) (a registered branch of the ESC). Eur J Echocardiogr 11:461–476. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejechocard/jeq045

Heidrich J et al (2007) Variations in the use of diagnostic procedures after acute stroke in Europe: results from the BIOMED II study of stroke care. Eur J Neurol 14:255–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01573.x

Leung DY et al (1995) Selection of patients for transesophageal echocardiography after stroke and systemic embolic events. Role of transthoracic echocardiography. Stroke 26:1820–1824

de Bruijn SF et al (2006) Transesophageal echocardiography is superior to transthoracic echocardiography in management of patients of any age with transient ischemic attack or stroke. Stroke 37:2531–2534. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.0000241064.46659.69

Harloff A et al (2006) Therapeutic strategies after examination by transesophageal echocardiography in 503 patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke 37:859–864. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000202592.87021.b7

Strandberg M et al (2002) Transoesophageal echocardiography in selecting patients for anticoagulation after ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 73:29–33

Herm J et al (2013) Should transesophageal echocardiography be performed in acute stroke patients with atrial fibrillation? J Clin Neurosci 20:554–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2012.03.049

Haeusler KG et al (2017) Feasibility and diagnostic value of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging after acute Ischemic stroke of undetermined origin. Stroke 48:1241–1247. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.016227

Baher A et al (2014) Cardiac MRI improves identification of etiology of acute ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 37:277–284. https://doi.org/10.1159/000360073

Sipola P et al (2013) Computed tomography and echocardiography together reveal more high-risk findings than echocardiography alone in the diagnostics of stroke etiology. Cerebrovasc Dis 35:521–530. https://doi.org/10.1159/000350734

Boussel L et al (2011) Ischemic stroke: etiologic work-up with multidetector CT of heart and extra- and intracranial arteries. Radiology 258:206–212. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.10100804

Hur J et al (2009) Cardiac computed tomographic angiography for detection of cardiac sources of embolism in stroke patients. Stroke 40:2073–2078. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.108.537928

Weinsaft JW et al (2016) Echocardiographic algorithm for post-myocardial infarction LV thrombus: a gatekeeper for thrombus evaluation by delayed enhancement CMR. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 9:505–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.06.017

Gianstefani S et al (2014) Incidence and predictors of early left ventricular thrombus after ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the contemporary era of primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 113:1111–1116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.12.015

Vaitkus PT, Barnathan ES (1993) Embolic potential, prevention and management of mural thrombus complicating anterior myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 22:1004–1009

Stratton JR, Resnick AD (1987) Increased embolic risk in patients with left ventricular thrombi. Circulation 75:1004–1011

Srichai MB et al (2006) Clinical, imaging, and pathological characteristics of left ventricular thrombus: a comparison of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, transthoracic echocardiography, and transesophageal echocardiography with surgical or pathological validation. Am Heart J 152:75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2005.08.021

Barkhausen J et al (2002) Detection and characterization of intracardiac thrombi on MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 179:1539–1544. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.179.6.1791539

Weinsaft JW et al (2009) Contrast-enhanced anatomic imaging as compared to contrast-enhanced tissue characterization for detection of left ventricular thrombus. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2:969–979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.03.017

Takasugi J et al (2017) Detection of left ventricular thrombus by cardiac magnetic resonance in embolic stroke of undetermined source. Stroke 48:2434–2440. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.117.018263

Goldstein JA et al (1986) Evaluation of left ventricular thrombi by contrast-enhanced computed tomography and two-dimensional echocardiography. Am J Cardiol 57:757–760

Bittencourt MS et al (2012) Left ventricular thrombus attenuation characterization in cardiac computed tomography angiography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 6:121–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcct.2011.12.006

Ponikowski P et al (2016) 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 37:2129–2200. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128

Natterson PD et al (1995) Risk of arterial embolization in 224 patients awaiting cardiac transplantation. Am Heart J 129:564–570

Katz SD et al (1993) Low incidence of stroke in ambulatory patients with heart failure: a prospective study. Am Heart J 126:141–146

Fuster V et al (1981) The natural history of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 47:525–531

Oechslin EN et al (2000) Long-term follow-up of 34 adults with isolated left ventricular noncompaction: a distinct cardiomyopathy with poor prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 36:493–500

Captur G, Nihoyannopoulos P (2010) Left ventricular non-compaction: genetic heterogeneity, diagnosis and clinical course. Int J Cardiol 140:145–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.07.003

Yoo J et al (2016) Poor outcome of stroke patients with atrial fibrillation in the presence of coexisting spontaneous echo contrast. Stroke 47:1920–1922. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013351

Paciaroni M et al (2016) Prognostic value of trans-thoracic echocardiography in patients with acute stroke and atrial fibrillation: findings from the RAF study. J Neurol 263:231–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-015-7957-3

Pritchett AM et al (2003) Left atrial volume as an index of left atrial size: a population-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol 41:1036–1043

Blackshear JL, Odell JA (1996) Appendage obliteration to reduce stroke in cardiac surgical patients with atrial fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg 61:755–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-4975(95)00887-x

Di Biase L et al (2012) Does the left atrial appendage morphology correlate with the risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation? Results from a multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol 60:531–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.032

Overvad TF et al (2016) Left atrial size and risk of stroke in patients in sinus rhythm. A systematic review. Thromb Haemost 116:206–219. https://doi.org/10.1160/th15-12-0923

Fatkin D, Kelly RP, Feneley MP (1994) Relations between left atrial appendage blood flow velocity, spontaneous echocardiographic contrast and thromboembolic risk in vivo. J Am Coll Cardiol 23:961–969

Agmon Y, Khandheria BK, Gentile F, Seward JB (2002) Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of patients with left atrial thrombus and sinus rhythm: experience in 20 643 consecutive transesophageal echocardiographic examinations. Circulation 105:27–31

Romero J et al (2013) Detection of left atrial appendage thrombus by cardiac computed tomography in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 6:185–194. https://doi.org/10.1161/circimaging.112.000153

Pathan F, Hecht H, Narula J, Marwick TH (2018) Roles of transesophageal echocardiography and cardiac computed tomography for evaluation of left atrial thrombus and associated pathology: a review and critical analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 11:616–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.12.019

Vira T et al (2018) Cardiac computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging vs. transoesophageal echocardiography for diagnosing left atrial appendage thrombi. Europace. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euy142

Kitkungvan D et al (2016) Detection of LA and LAA thrombus by CMR in patients referred for pulmonary vein isolation. Jacc Cardiovasc Imaging 9:809–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.11.029

Ohyama H et al (2003) Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and transesophageal echocardiography in detection of thrombus in the left atrial appendage. Stroke 34:2436–2439. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.0000090350.73614.0f

Mas JL et al (2001) Recurrent cerebrovascular events associated with patent foramen ovale, atrial septal aneurysm, or both. N Engl J Med 345:1740–1746. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa011503

Hagen PT, Scholz DG, Edwards WD (1984) Incidence and size of patent foramen ovale during the first 10 decades of life: an autopsy study of 965 normal hearts. Mayo Clin Proc 59:17–20

Handke M et al (2007) Patent foramen ovale and cryptogenic stroke in older patients. N Engl J Med 357:2262–2268. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa071422

Ntaios G et al (2018) Closure of patent foramen ovale versus medical therapy in patients with ccryptogenic stroke or transient Ischemic attack: updated systematic review and Meta-analysis. Stroke 49:412–418. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.117.020030

Lee PH et al (2018) Cryptogenic stroke and high-risk patent foramen ovale: the DEFENSE-PFO trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 71:2335–2342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.046

Diener HC et al (2018) Cryptogenic stroke and patent foramen ovale : S2e guidelines. Nervenarzt 89:1143–1153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-018-0609-y

Maffe S et al (2010) Transthoracic second harmonic two- and three-dimensional echocardiography for detection of patent foramen ovale. Eur J Echocardiogr 11:57–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejechocard/jep165

Kim YJ et al (2009) Patent foramen ovale: diagnosis with multidetector CT—comparison with transesophageal echocardiography. Radiology 250:61–67. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2501080559

Hamilton-Craig C et al (2011) Contrast transoesophageal echocardiography remains superior to contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of patent foramen ovale. Eur J Echocardiogr 12:222–227. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejechocard/jeq177

Nusser T et al (2006) Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and transesophageal echocardiography in patients with transcatheter closure of patent foramen ovale. J Am Coll Cardiol 48:322–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.036

Habib G et al (2015) 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J 36:3075–3128. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319

Snygg-Martin U et al (2008) Cerebrovascular complications in patients with left-sided infective endocarditis are common: a prospective study using magnetic resonance imaging and neurochemical brain damage markers. Clin Infect Dis 47:23–30. https://doi.org/10.1086/588663

Grabowski M, Hryniewiecki T, Janas J, Stepinska J (2011) Clinically overt and silent cerebral embolism in the course of infective endocarditis. J Neurol 258:1133–1139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5897-5

Duval X et al (2010) Effect of early cerebral magnetic resonance imaging on clinical decisions in infective endocarditis: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med 152:497–504, w175. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-152-8-201004200-00006

Dickerman SA et al (2007) The relationship between the initiation of antimicrobial therapy and the incidence of stroke in infective endocarditis: an analysis from the ICE Prospective Cohort Study (ICE-PCS). Am Heart J 154:1086–1094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.023

Bai AD et al (2017) Diagnostic accuracy of transthoracic echocardiography for infective endocarditis findings using transesophageal echocardiography as the reference standard: a meta-analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 30:639–646.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2017.03.007

Rohmann S et al (1991) Prediction of rapid versus prolonged healing of infective endocarditis by monitoring vegetation size. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 4:465–474

Mohananey D et al (2018) Association of vegetation size with embolic risk in patients with infective Endocarditis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 178:502–510. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8653

Feuchtner GM et al (2009) Multislice computed tomography in infective endocarditis: comparison with transesophageal echocardiography and intraoperative findings. J Am Coll Cardiol 53:436–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.077

Habets J et al (2015) Are novel non-invasive imaging techniques needed in patients with suspected prosthetic heart valve endocarditis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 25:2125–2133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-3605-7

Bruun NE, Habib G, Thuny F, Sogaard P (2014) Cardiac imaging in infectious endocarditis. Eur Heart J 35:624–632. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht274

Durrleman N et al (2004) Prosthetic valve thrombosis: twenty-year experience at the Montreal Heart Institute. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 127:1388–1392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.12.013

Puvimanasinghe JP et al (2001) Prognosis after aortic valve replacement with a bioprosthesis: predictions based on meta-analysis and microsimulation. Circulation 103:1535–1541

Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR, Briet E (1994) Thromboembolic and bleeding complications in patients with mechanical heart valve prostheses. Circulation 89:635–641

Lim WY, Lloyd G, Bhattacharyya S (2017) Mechanical and surgical bioprosthetic valve thrombosis. Heart 103:1934–1941. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311856

Lam KY, Dickens P, Chan AC (1993) Tumors of the heart. A 20-year experience with a review of 12,485 consecutive autopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med 117:1027–1031

Pinede L, Duhaut P, Loire R (2001) Clinical presentation of left atrial cardiac myxoma. A series of 112 consecutive cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 80:159–172

Klarich KW et al (1997) Papillary fibroelastoma: echocardiographic characteristics for diagnosis and pathologic correlation. J Am Coll Cardiol 30:784–790

Hoey ET et al (2009) MRI and CT appearances of cardiac tumours in adults. Clin Radiol 64:1214–1230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2009.09.002

Gowda RM et al (2003) Cardiac papillary fibroelastoma: a comprehensive analysis of 725 cases. Am Heart J 146:404–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-8703(03)00249-7

Engberding R et al (1993) Diagnosis of heart tumours by transoesophageal echocardiography: a multicentre study in 154 patients. European Cooperative Study Group. Eur Heart J 14:1223–1228

Hahn RT et al (2013) Guidelines for performing a comprehensive transesophageal echocardiographic examination: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 26:921–964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2013.07.009

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

S. Camen declares that he has no conflict of interests. R. B. Schnabel has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 648131), German Ministry of Research and Education (BMBF 01ZX1408A), and German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK e.V.) (81Z1710103). R. B. Schnabel further reports lecture/advisory board fees from BMS/Pfizer. K.G. Haeusler reports study grants by Bayer and Sanofi-Aventis, lecture fees/advisory board fees from Sanofi-Aventis, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Edwards Lifesciences, Biotronik, and Medtronic.

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Camen, S., Haeusler, K.G. & Schnabel, R.B. Cardiac imaging after ischemic stroke. Herz 44, 296–303 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-019-4803-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-019-4803-x

Keywords

- Brain ischemia

- Computed tomography, X‑ray

- Embolism

- Magnetic resonance imaging

- Echocardiography, transesophageal