Abstract

Objectives

This qualitative investigation documents Bulgarian perspectives on public health following its accession to the European Union (EU) and explores perceived obstacles to the modernization of public health sciences to more effectively address the country’s high rates of premature avoidable mortality.

Methods

28 semi-structured interviews were conducted throughout Bulgaria in April 2007 with Bulgarian academics, clinicians, policymakers and students in Sofia, Varna and Pleven. Full transcripts were subjected to formal thematic analysis.

Results

Respondents identified various barriers to the development and modernization to public health infrastructures in Bulgaria that were classified by four key interlinked themes: (1) institutional and political, (2) financial, (3) dearth of local epidemiological studies, and (4) insufficient public health capacity.

Conclusions

This study is the first to explore specific perspectives and beliefs regarding barriers to the development, modernization, and utilization of public health sciences in Bulgaria. Although the reorientation and strengthening of public health institutions are unlikely to proceed without resistance, optimism for improvement in this field exists now that Bulgaria has joined the EU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bulgaria, a former communist country located in southeastern Europe, entered the European Union (EU) in January 2007. The majority of the transitional period since 1989 was marked by political instability, corruption and severe economic hardship (Georgieva et al. 2007). Bulgaria was one of the last countries among the new post-communist EU member states (EU8+2) to regain its pre-transition GDP level (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development 2008). Mass impoverishment and an ineffective medical system have contributed materially to stagnating population health indicators. High premature mortality, low birth rates and extensive emigration of predominantly young economically active people have resulted in an ageing of the population and a rapid decrease of its size from 8.987 million at the end of 1988 to 7.640 million at the end of 2007 (National Center for Health Information 2007; Georgieva et al. 2002; National Statistical Institute 2008).

Although Bulgaria is now officially part of the EU, a formidable gap exists between the health status of its population and that of the older EU member states (EU15), especially with respect to the country’s alarming cardiovascular disease (CVD) burden (Georgieva et al. 2007; Stein et al. 2000). While life expectancy at birth in the West (EU15) has been steadily improving and was 77 years for men in 2006, the life expectancy of Bulgarian males corresponds with its 1970 level of 69 years (WHO 2009). Of the gap in life expectancy at birth in 2002 between Bulgaria and the combined EU15, over 80% originated from differences in mortality from CVD alone, namely myocardial infarction and stroke (Zatonski et al. 2008). Bulgaria’s inability to control non-communicable disease (NCD) risks contrasts with the recent experience of other post-communist states such as Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Slovenia where there have been substantial recent declines in mortality from CVD (Zatonski et al. 2008).

Furthermore, risk factor awareness remains low within Bulgaria (Stein et al. 2000; Dokova et al. 2005). Additionally, research and training opportunities in public health sciences basic to the control of vascular risk (notably CVD epidemiology) remain limited (Dokova et al. 2005; Rechel and McKee 2003). Preventive programs targeting long-known modifiable risk factors including high blood pressure, smoking, high cholesterol, high saturated fat and salt intake and low fruit and vegetable consumption have not sufficiently addressed the population’s health risk behaviors (Georgieva et al. 2002; Stein et al. 2000; Dokova et al. 2005; Rechel and McKee 2003; Powles et al. 2005).

Nearly 20 years after the ‘fall of the Wall’, Bulgaria continues to struggle with reconstructing its Soviet era public health infrastructure (Georgieva et al. 2007). The Semashko model public health system of the communist period was designed in the first half of the twentieth century to deal principally with maternal and child health and communicable diseases (Field 1967). In post-war Bulgaria, this system was developed and deployed in isolation from western advances in NCD epidemiology and modern public health initiatives. Clinical services have also remained largely untouched by the concepts of evidence-based medicine (McKee 2007; Terris 1988). The following explanation of Bulgaria’s current public health infrastructure and public health financing provides important context to the barriers identified in this study.

Current public health infrastructure

Bulgaria’s public health network consists of 28 Regional Inspectorates of Public Health Protection and Inspection, which are centrally managed by the Ministry of Health, and responsible for control of communicable diseases, health promotion and disease prevention. National health programs are implemented by these 28 Regional Health Centers. There are four national centers for health protection including the National Center for Public Health Protection, the National Center for Infectious and Parasitic Diseases, the National Council on Narcotic Drugs, and the National Center for Radiobiology and Radiation Protection (Georgieva et al. 2007). Additionally, there are five medical universities with public health departments and a large number of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) active in the health sector. Bulgaria’s National Health Promotion Strategy for 2007–2012 focuses on immunization, screening programs and ‘regular medical check-ups’ (Georgieva et al. 2007). However, this document has been criticized for its inconformity with the principles of evidence-based policy making (Salchev et al. 2008). Specifically, screening coverage is low, at least in the case of cervical screening (Todorova et al. 2009), and health promotion programs lack the commitment needed to achieve substantial reductions in CVD risk. The introduction of clinical pathways as a payment mechanism for hospitals through the National Health Insurance Fund has led to distortion of morbidity statistics due to preferential coding of diagnoses that are reimbursed at a higher rate and this may complicate the monitoring of disease outcomes related to prevention programs (Rechel 2009).

Financial context for public health

In the 1990s, the Bulgarian healthcare system was chronically underfunded due to the overall economic recession. Public expenditure on health services as a percentage of GDP fell to 3.5% of GDP in 1998, a figure much lower than the EU15 average of 8.6%. The introduction of a national health insurance system in 1998 aimed to increase the health services budget and ensure stability in financing the sector. Nevertheless, expenditures on health services from the state budget in Bulgaria are still low compared to other EU countries, representing 4.3% of GDP in 2007 (Ministry of Health 2008). In 2004, average public expenditure on health services in the EU15 was 2,089 USD (purchasing power parity, PPP) per capita, while in Bulgaria it was 386 USD (PPP) per capita, considerably lower than the EU(8+2) average of 625 USD (PPP) (WHO 2009). In this situation, the development of internally funded public health initiatives is not likely without major political commitment. The absence of local cost-effectiveness studies also makes it more difficult to convince policymakers that proven preventive programs are likely to be more cost-effective than treatment services.

In spite of increasing exposure to modern public health sciences through international collaborative training and research projects since 1989, the tools of epidemiology and evidence-based medicine remain underutilized in Bulgaria (Stein et al. 2000). From an external point of view, it is difficult to understand why these tools of modern public health have not been used to address Bulgaria’s heavy burden of avoidable disease. This is the first documented study that employs an internal qualitative methodology to gain insight into these complex issues.

Methods

Theoretical framework

Literature on the transition of the medical and public health systems in central and eastern Europe as well as the former Soviet Union informed this study’s theoretical framework. The healthcare system reforms of these countries focused mainly on changes in the financing systems and introduction of general practice-based primary care (Rechel and McKee 2009). Addressing the wider determinants of health through health-promoting public policies has received much less attention throughout the transition period (Rechel and McKee 2003). As Rivkin-Fish observed, many reforms undermined collective models of action and societal forms of responsibility in the post-Soviet era (Rivkin-Fish 2005). Lifestyle risk factors such as diet, exercise, smoking, and heavy drinking have been suggested to have a major role in the higher morbidity and mortality from preventable causes (Boys et al. 1991; McKee 1999; Perlman et al. 2007; Perlman and Bobak 2008; Georgieva et al. 1999; Cockerham 1999). The public health service in the former Soviet Union was based on sanitary-epidemiological stations, dealing primarily with communicable disease control and environmental health (Tkatchenko et al. 2000; Garrett 2001). Epidemiology was not applied to studying and preventing NCD, and rigorous quantitative methodologies were not employed in research (McKee 2007; Garrett 2001). Furthermore, public health strategies were dominated by medical models rather than adopting multi-sectoral approaches (Terris 1988; Tkatchenko et al. 2000).

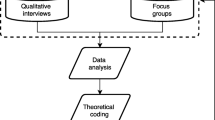

A qualitative research investigation was deemed most appropriate to learn about the perceptions regarding public health challenges within Bulgaria. We set out to explore the following research questions based on the aforementioned theoretical framework: How are the concepts of epidemiology and evidence-based medicine understood and applied to public health practice in Bulgaria? What are the perceived barriers to the development of modern public health sciences in Bulgaria? A topic guide was developed which sought to elicit: (1) awareness about the current major public health problems in Bulgaria; (2) current understanding of the terms “public health” and “epidemiology”; (3) perceptions about the value, necessity, generation and utilization of epidemiological evidence; and (4) the perceived barriers to the development of capacity in modern public health sciences in the context of EU integration. Through purposive and snowball sampling, we identified participants from each of the following levels of the healthcare system with positions relevant to public health: policymakers from governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (n = 10), practicing clinicians (n = 4), academics (n = 8) and students (n = 6). In April 2007, 28 semi-structured interviews (M 11, F 17) were conducted by KWS in English in Sofia (n = 15), Varna (n = 7), and Pleven (n = 6)—three cities in Bulgaria with medical universities and public health faculties. Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, coded and analysed, also by KWS, using a grounded thematic analytic approach (Cronin et al. 2008). The conduct of the study followed established ethical guidelines (British Sociological Association 2002). All data presented here come from respondents who signed the informed consent document designed for this study and their anonymity was strictly maintained. Despite numerous enquiries, no appropriate ethics committee in Bulgaria was identified at the time of the research. The Bulgarian Sociological Association (2007) was subsequently identified and approval for the research was granted.

Results

We focus on perceived obstacles to the development and modernization of public health, as they emerged from participants’ accounts. Respondents identified numerous historical, traditional and policy-related barriers, which were categorized into the following interlinked themes: (1) institutional and political, (2) financial, (3) dearth of local epidemiological studies, and (4) insufficient public health capacity barriers.

Theme #1: institutional and political barriers

As in other countries from the former Soviet bloc, epidemiology in Bulgaria has traditionally focused on communicable diseases, which constituted the greatest health concern prior to the 1960s. As one academic in Sofia stated, Bulgarian politicians “developed wonderful structures and prepared professionals to work with the problems of that time,” yet these dated policies, in the words of the respondents, have influenced policymakers a half century later in a way that prevents current policies “in strong and pointless ways” from adequately addressing the “changing realities” facing the country today. The majority of participants in this study noted that the limited concept that epidemiology and health surveillance only apply to communicable diseases remains, in spite of the immense NCD burden within the country. When asked about their views on epidemiology, leading health policymakers that had no record of modern public health training discussed exclusively surveillance of communicable diseases or identified “preparedness for pandemic influenza” or outbreaks of Hepatitis A as “all the main challenges” in public health. In contrast, respondents who had formal training in public health or epidemiology from abroad (n = 7) or had been directly involved with internationally initiated epidemiological studies within Bulgaria (n = 6) referred to this traditional epidemiological mindset that focuses on communicable diseases as an obstacle to the modernization of public health within the country (Table 1, Quote 1a).

Other traditional forms of governance continue to hinder the development of modern public health. Several participants described how a public debate on health matters has been absent—“we have never been used to making evidence-based planning,” everything was “simply decided.” Similar concerns that political interests continue to curb utilization of evidence in health policy formation were noted (Table 1, Quote 1b).

Lack of active public health legislation and weak enforcement of such legislation emerged as other important barriers to the modernization of public health sciences. A clinician from Sofia articulated other respondents’ concerns that while public health measures may be cited in official policy documents (i.e. anti-smoking initiatives), these remain “only in the books” and are “not strictly implemented in real life.” Another respondent stressed the controversy that while addressing CVD is listed as a priority in national strategic health documents, these policies are only “good wishes” as they are neither enforced nor bolstered by concrete implementation programs (Table 1, Quote 1c).

Several academics and policymakers described a lack of “horizontal collaboration” between ministries and departments as a hurdle for implementing effective health policy. A policymaker involved in a variety of international epidemiological investigations explained that public health in Bulgaria remains the sole responsibility of a limited health or medical sector rather than involving other sectors to develop more holistic policies that adequately address public health challenges (Table 1, Quote 1d). Further, he and other respondents noted that a “drawback” of Bulgaria’s National Health Strategy 2007–2012 was that this issue was not “dealt with seriously” (Table 1).

Theme #2: financial

Every respondent referenced Bulgaria’s challenging socio-economic situation as a major factor affecting the field of public health. Academics and clinicians expressed concerns that scientific research is poorly financed, especially epidemiological investigations. These financial challenges were explained as (1) due to Bulgaria’s “poor” economic condition (Table 2, Quotes 2a, 2b), as well as (2) an inability to “value” epidemiological studies that aim to better understand Bulgarian-specific health challenges (Table 2, Quote 2c). All respondents felt that improving Bulgaria’s economic condition (i.e. an anticipated outcome of EU accession and health reform opportunities) could have a positive effect on public health initiatives within the country. Interestingly, however, one respondent cautioned that this narrow focus on Bulgarian economic reform might further delay necessary advancements in the traditionally underfunded public health sector (Table 2, Quote 2d).

Theme #3: dearth of local epidemiological studies

The lack of nationally initiated, high-quality public health research emerged as a major concern to many participants, specifically the insufficient effort to collect quality local data regarding NCD (Table 3, Quote 3a). Primarily those respondents that had obtained formal training in epidemiology and public health from abroad (n = 7) discussed the “poor quality” of the current state of Bulgarian-specific research. They and others noted the limited English-speaking capacity within Bulgaria as a potential limitation to Bulgaria’s ability to access and learn from international research that may enhance familiarity with the application of modern public health sciences (Table 3, Quote 3b). This restricted access, combined with the “lack of locally generated reliable data,” was perceived to be a crucial obstacle to evidence-based clinical and public health practice. In spite of these concerns, many were optimistic that Bulgaria’s recent accession to the EU could positively affect this trend (Table 3, Quote 3c).

Theme #4: insufficient public health capacity

Almost every respondent stated that Bulgaria suffers from a deficiency in specialists trained in modern public health and epidemiology. Surprisingly, one policymaker in Sofia noted that financial resources may not be the limiting factor, but rather the limited human resources dedicated to this field (Table 4, Quote 4a).

Respondents expressed their concerns with the fact that older physicians, who tend to be unfamiliar with modern public health disciplines, almost exclusively occupied the leading health policymaking positions in Bulgaria. An academic from Pleven stated that these “older generation doctors” in health policy leadership “do not know much about epidemiology.” Consequently, respondents felt that these policymakers have limited ability to utilize and appreciate epidemiological findings as they direct the formation of Bulgarian health policy (Table 4, Quote 4b).

Some academics noted that Bulgaria currently has limited capabilities to provide quality training in epidemiology as most of the senior academic staff “do not have formal training in epidemiology so they cannot be useful to their PhD students as tutors.” Contrasting this apparent lack of capacity, those who had received public health training abroad stated that there currently exists little demand for professionals trained in modern public health within the country. Degrees earned abroad “were not recognized” in Bulgaria and “did not mean anything” to their colleagues and officials within their institutions. Concerns that a formal education in public health is not valued, appreciated and utilized in the country were clearly indicated (Table 4, Quote 4c). Low salaries and the “lack of perspective, incentives or career possibilities” undermine young professionals’ motivation to work in public health. For example, a recent graduate of a public health program abroad discussed his “second thoughts” about remaining in the field after he realized how “very hard” it would be to pursue a career within Bulgaria, “especially outside of Sofia.”

Broad EU optimism

Despite these documented perceived challenges and barriers, nearly every respondent optimistically discussed the potential role of the EU to advance Bulgaria’s development of modern public health sciences. For instance, when asked to share her perspectives on Bulgaria’s future with respect to public health, an academic from Pleven summarized her optimism for inevitable improvement to the field as a result of Bulgaria’s entrance into the EU (Table 5, Quote 5a). Interestingly, a policymaker who also captured the respondents’ commonly stated optimism articulated that if Bulgaria fails to address these public health burdens internally, then the presence of the EU as an external force will demand and thus provoke necessary change within the field of public health (Table 5, Quote 5b).

Discussion

Main findings

This investigation documents the existence of substantial perceived historical, political, financial and institutional barriers to utilizing public health sciences for improving population health within Bulgaria—especially those required to promote effective control over the country’s most common preventable causes of premature death.

Many respondents from the older generations referred to former Soviet influence when considering the weak development of public health within the country today, implicitly acknowledging a profound institutional conservatism. Although all the ten post-communist countries now within the EU have experienced the epidemiological transition from communicable diseases to NCD, the Soviet tradition of applying epidemiological principles to only communicable diseases continues to hinder advancement of this discipline (Delnoij et al. 2003). As early as 1988, Terris (1988) made strikingly similar observations on the limiting nature of the Semashko heritage.

Participants articulated their concern that the lack of local exemplar population-based studies meant that their utility to the implementation of national health programs could not be demonstrated. As such, these epidemiological studies are not funded and thus cannot be shown to be of value within Bulgaria.

Respondents from all backgrounds believed that Bulgaria’s socio-economic situation had a negative effect upon the development of public health infrastructures, yet were optimistic that EU membership may help reverse this trend. Academics and policymakers who had participated in international epidemiological investigations or had trained for their public health degrees abroad highlighted an urgent need to build public health capacity within the country. Alternatively, all interviewed students with a potential interest in public health (n = 6) either noted a concern that there would be “no place for them” or expressed plans to leave Bulgaria in order to pursue their career. Despite these various perceived barriers, respondents consistently noted that being part of the EU offers new opportunities and fresh optimism to address and overcome these barriers.

Comparison with existing literature

While similar barriers and challenges facing Bulgaria have been referenced from an external standpoint (Georgieva et al. 2002, 2007; Rechel and McKee 2003), this is the first documented investigation to characterize internal perceived barriers to the modernization and utilization of public health sciences to address NCD within the country. Our findings corroborate observations regarding challenges to public health research in other countries of southeastern Europe that include insufficient funding, lack of expertise and lack of quality local data (Burazeri et al. 2009).

Respondents’ concerns with government strategies associated with public health cited in this study are important to consider in the context of Bulgaria’s current public health infrastructure and its National Health Strategy as previously described. Specifically, respondents in our study expressed concerns that routine health statistics are not sufficient to inform public health policy on NCD since they are limited to mortality data (Table 3, Quote 3a). Internal negative perspectives regarding government effectiveness as cited by respondents are consistent with Bulgaria’s previous poor rankings on this measure (World Bank 2008).

Bulgaria’s poor economic situation as a barrier to the development of modern public health sciences identified in this study has also been noted elsewhere (Rechel and McKee 2003). Participants commented on being limited to studies funded by the non-governmental sector, regional or external funding agencies, or pharmaceutical companies as financing of the public health sector remains poor.

Public health capacity building

Respondents’ concerns with the lack of identity or a professional place for public health specialists and epidemiologists in Bulgaria are consistent with previous findings (Popova et al. 2004). Studies specifically investigating Bulgaria’s public health capacity have noted shortages of public health professionals in spite of an increasing awareness of the discipline within the country (Vankova and de Leeuw 2001). Some reports have described Bulgaria’s efforts to develop postgraduate training in public health as successes for the country (Rechel and McKee 2003; Vankova and de Leeuw 2001); however, this investigation reveals useful internal data suggesting that this advanced training has not been properly “recognized”, “valued” or utilized. Such challenges may help explain why the 1992-95 EU-funded Trans European Mobility Scheme for University Studies (TEMPUS) project, which aimed to boost public health capacity by training individuals in modern public health sciences, has not been as successful as originally expected (Vankova and de Leeuw 2001). There appears to be a conflict in that Bulgarian officials recognize a need for more public health professionals within the country, yet young professionals have “no motivation” to enter the field since there appears to be insufficient opportunity for professional development. Such a sentiment may relate to a lack of transparent and meritocratic recruitment procedures in the country where corruption is recognized by two-thirds of citizens as the single most serious problem facing Bulgaria (Center for the Study of Democracy 2009).

In spite of these referenced barriers, an equally important finding is the overwhelming optimism that Bulgaria’s entrance into the EU will help motivate the necessary changes that public health specialists desire for the country, a sentiment consistent with previous reports (McKee et al. 2007). Recently, Bulgaria has joined a number of cross-national public health projects including the European Network for Workplace Health Promotion since 1998, the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs since 1999, the Health Behavior in School-aged Children study network since 2004, and the European Health Literacy Survey since 2009. Bulgaria’s increasing involvement in international research ventures grounded in modern epidemiology further underscores reason for optimism as such involvement will motivate prioritization of building this capacity to meet future demands.

Summary

Although Bulgaria is now part of the EU, this investigation reveals that great strides must be taken within the country to ensure a greater internal capacity to develop, utilize, invest in and rely upon modern public health sciences to combat its leading challenges, notably those of CVD. The public health community of Bulgaria must better collaborate to develop strategies to translate research and evidence into inter-sectoral public health policies. Bulgaria should, therefore, capitalize on its EU member status and involvement in international research collaborations to invest in programs, training incentives and professional development for individuals who are prepared, and those willing to be prepared, to address, investigate, and mitigate the public health problems facing the country, most notably, its preventable CVD burden. Their optimism may be warranted, but not without great effort.

Limitations of this study

This study’s major limitation involved the fact that it was not possible to communicate directly with potential Bulgarian-speaking respondents whose backgrounds and experiences may have been extremely relevant to this research question but unattainable due to the language barrier.

References

Boys RJ, Forster DP et al (1991) Mortality from causes amenable and non-amenable to medical care: the experience of eastern Europe. BMJ 303(6807):879–883

British Sociological Association (2002) Statement of ethical practice for the British Sociological Association. British Sociological Association, Durham

Bulgarian Sociological Association (2007) Statement of ethical practice for the Bulgarian Sociological Association (in Bulgarian). Available at http://www.bsa-bg.org/. Accessed 15 February 2009

Burazeri G, Brand H, Laaser U (2009) Public health research needs and challenges in transitional countries of South Eastern Europe. Italian J Public Health 6(1):48–51

Center for the Study of Democracy (2009) Crime without punishment: countering corruption and organized crime in Bulgaria. Center for the Study of Democracy, Sofia

Cockerham W (1999) Health and social change in Russia and Eastern Europe. Routledge, New York

Cronin A, Alexander VD, Fielding J, Moran-Ellis J, Thomas H (2008) The analytic integration of qualitative data sources. In: Alasuutari P, Bickman L, Brannen J (eds) The Sage handbook of social research methods. Sage Publications, London

Delnoij DM, Klazinga NS, van der Velden K (2003) Building integrated health systems in central and eastern Europe: an analysis of WHO and World Bank views and their relevance to health systems in transition. Eur J Public Health 13(3):240–245

Dokova KG, Stoeva KJ, Kirov PI, Feschieva NG, Petrova SP, Powles JW (2005) Public understanding of the causes of high stroke risk in northeast Bulgaria. Eur J Public Health 15(3):313–316

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Country factsheets (2008) Available on http://www.ebrd.com/country/index.htm. Accessed 1 March 2009

Field MG (1967) Soviet socialized medicine: an introduction. Free Press, New York

Garrett L (2001) Bourgeois physiology: the collapse of all semblances of public health in the former Soviet Socialist Republics. In: Garrett L (ed) Betrayal of trust: the collapse of global public health. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Georgieva L, Powles JW et al (1999) Fruit and vegetables and ischaemic heart disease in Eastern Europe a hospital-based case control study in Sofia, Bulgaria. Cent Eur J Public Health 7(2):87–90

Georgieva L, Powles JW, Genchev G, Salchev P, Poptodorov G (2002) Bulgarian population in transitional period. Croat Med J 43(2):240–244

Georgieva L, Salchev P, Dimitrova S, Dimova A, Avdeeva O (2007) Bulgaria: health system review. Health Syst Transition 9(1):1–156

McKee M (1999) Alcohol in Russia. Alcohol Alcohol 34(6):824–829

McKee M (2007) Cochrane on communism: the influence of ideology on the search for evidence. Int J Epidemiol 36(2):269–273

McKee M, Balabanova D, Steriu A (2007) A new year, a new era: Romania and Bulgaria join the European Union (editorial). Eur J Public Health 17(2):119–120

Ministry of Health (2008) Health priority investment in the future of the nation. Annual report of the Minister of Health (in Bulgarian). Ministry of Health, Sofia

National Center for Health Information (2007) Public health statistics annual 2006. National Center for Health Information, Sofia

National Statistical Institute (2008) Population and demographic processes in 2007 (in Bulgarian). NSI, Sofia. Available on http://www.nsi.bg/Population/Population07.htm. Accessed 20 February 2009

Perlman F, Bobak M (2008) Socioeconomic and behavioral determinants of mortality in posttransition Russia: a prospective population study. Ann Epidemiol 18(2):92–100

Perlman F, Bobak M et al (2007) Trends in the prevalence of smoking in Russia during the transition to a market economy. Tob Control 16(5):299–305

Popova S, Kerekovska A, Feschieva N, Mircheva I (2004) Public health training needs assessment in Bulgaria: a necessary and continuous process. Scripta Sci Med 36:61–64

Powles JW, Zatonski W, Vander Hoorn S, Ezzati M (2005) The contribution of leading diseases and risk factors to excess losses of healthy life in Eastern Europe: burden of disease study. BMC Public Health 5:116

Rechel B (2009) Inequalities in access to health care for children in Bulgaria. PhD Thesis. University of Warwick

Rechel B, McKee M (2003) Healing the crisis: a prescription for public health in South Eastern Europe. London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London

Rechel B, McKee M (2009) Health reform in central and eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Lancet 374(9696):1186–1195

Rivkin-Fish M (2005) Women’s health in post-Soviet Russia: the politics of intervention. Indiana University Press, Bloomington

Salchev P, Hristov N, Georgieva L (2008) Evidence based policy-practical approaches. The Bulgarian National Health Strategy 2007–2012. Medical University of Sofia, Sofia

Stein AD, Stoyanovsky V, Mincheva V, Dimitrov E, Hodjeva D, Petkov A et al (2000) Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in a working Bulgarian population. Eur J Epidemiol 16(3):265–270

Terris M (1988) Restructuring and accelerating the development of the Soviet Health Service: preliminary observations and recommendations. J Public Health Policy 9(4):537–543

Tkatchenko E, McKee M et al (2000) Public health in Russia: the view from the inside. Health Policy Plan 15(2):164–169

Todorova I, Baban A, Alexandrova-Karamanova A, Bradley J (2009) Inequalities in cervical cancer screening in Eastern Europe: perspectives from Bulgaria and Romania. Int J Public Health 54:222–232

Vankova D, de Leeuw E (2001) Public health human capacity building in Bulgaria—theory and application of SWOT analysis. Internet J Public Health Educ 3:B18–B48

WHO (2009) Health for All Database. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen

World Bank (2008) Worldwide Governance Indicators 1996–2007. Available on http://go.world/bank.org/ATJXPHZMH0. Accessed 5 May 2009

Zatonski W, Manczuk M, Sulkowska U et al (2008) Closing the health gap in European Union Closing the Gap—reducing premature mortality. Baseline for Monitoring Health Evolution Following Enlargement, Warsaw

Acknowledgments

This project was partially financed by the Department of Public Health & Primary Care and Churchill College of the University of Cambridge. The authors wish to thank the interviewees who remain nameless in this study yet are deserving of our greatest appreciation as this project would have been impossible without their participation.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scott, K.W., Powles, J., Thomas, H. et al. Perceived barriers to the development of modern public health in Bulgaria: a qualitative study. Int J Public Health 56, 191–199 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-010-0140-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-010-0140-9