Abstract

We perform earthquake cycle simulations with the goal of studying the characteristics of source scaling relations and strong ground motions in multi-segmented fault ruptures. The 1992 Mw 7.3 Landers earthquake is chosen as a target earthquake to validate our methodology. The model includes the fault geometry for the three-segmented Landers rupture from the SCEC community fault model, extended at both ends to a total length of 200 km, and limited to a depth to 15 km. We assume the faults are governed by rate-and-state (RS) friction, with a heterogeneous, correlated spatial distribution of characteristic weakening distance Dc. Multiple earthquake cycles on this non-planar fault system are modeled with a quasi-dynamic solver based on the boundary element method, substantially accelerated by implementing a hierarchical-matrix method. The resulting seismic ruptures are recomputed using a fully-dynamic solver based on the spectral element method, with the same RS friction law. The simulated earthquakes nucleate on different sections of the fault, and include events similar to the Mw 7.3 Landers earthquake. We obtain slip velocity functions, rupture times and magnitudes that can be compared to seismological observations. The simulated ground motions are validated by comparison of simulated and recorded response spectra.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Due to the lack of dense recordings of strong ground motions in the vicinity of faults, numerical modeling is a necessary tool for the assessment of variability of strong ground motions in potentially devastating large earthquakes. In a simulation-based seismic hazard analysis, it is critical to be able to generate a large number of physically self-consistent source models whose rupture process captures the main physics of earthquake rupture and is consistent with the spatio-temporal heterogeneity of past earthquakes (e.g. Field 2019). Such a set of source models can be used for verification of assumptions underlying strong ground motion simulation schemes (e.g. Irikura and Miyake 2011) and for constraining seismic source inversion. A wide range of physics-based models have been used for this purpose.

Ideally such modeling includes current knowledge of earthquake source physics, sufficiently accurate simulation of the radiated wave field, and a spatially variable, realistic distribution of near-surface geologic conditions. With the aim of including the physical mechanisms governing the rupture process, kinematic and dynamic rupture modeling has been applied to compute ground motions (Andrews 1976; Dalguer et al. 2007; Galvez et al. 2016; Ely et al. 2010; Olsen et al. 1997; Oglesby et al. 2012; Ripperger et al. 2008; Shi and Day 2013; Wollherr et al. 2018).

It is relatively straightforward to generate kinematic rupture models with a certain level of earthquake slip heterogeneity (Irikura and Miyake 2011; Somerville et al. 1999), but this kinematic approach uses simplified assumptions about the temporal evolution of the rupture process and often fails to capture the essential physics of earthquake rupture. In a recent multi-fault rupture event (the Mw 7.8 Kaikoura earthquake), the rupture propagated on many different fault branches and was arrested due to unfavorable orientation of these branches with respect to the regional tectonic stress (Ando and Kaneko 2018; Ulrich et al. 2019). These complex multi-segment rupture processes are difficult to incorporate consistently in kinematic rupture modeling, as the dynamic stress distribution is not included. Another pitfall of kinematic modeling is that it does not address the question of how large the rupture will grow and which branches will break during the rupture process.

In addition to heterogeneous stress distribution, correlation between different source parameters, such as peak slip rate, final slip and rupture velocity, is also present during the earthquake rupture (Gabriel et al. 2013; Song et al. 2013). Recent attempts to include the dependence of source parameters on local fault geometry have been performed in pseudo-dynamic rupture models by Trugman and Dunham (2014) and with 2-point statistics by Song et al. (2014). Even though pseudo-dynamic modeling enhances the incorporation of elements of earthquake source physics, it requires large catalogs of dynamic models to obtain reliable correlations between source parameters (Trugman and Dunham 2014).

Dynamic rupture modeling produces a physically self-consistent model for a single earthquake, given a set of dynamic input parameters describing initial stresses and a friction law. However, assigning initial conditions for each dynamic simulation is not trivial and often requires additional assumptions. A common attempt to set up initial stress conditions is by using stochastic distributions. For instance, Bauman and Dalguer (2014) generated a set of 300 dynamic rupture models by varying the normal stress and initial shear-stress using Von Karman stochastic distribution. However, this way of setting initial stress conditions does not incorporate the residual stress left by previous events and as a result the earthquake magnitude and rupture process can be biased.

From the standpoint of earthquake physics, the potential complexity of the problem requires an initial approach based on a simplified yet versatile mechanical model. Many previous efforts have been focused on studying the effects of heterogeneities in fault strength and initial stress on dynamic rupture models, while keeping the assumed friction laws as simple as possible (e.g. Ripperger et al. 2007, 2008; Olsen et al. 1997; Oglesby et al. 2012; Dalguer et al. 2007; Shi and Day 2013; Ely et al. 2010; Wollher et al. 2018; Andrews and Ma 2016; Ulrich et al. 2019). Such efforts are based on single-rupture dynamic models in which heterogeneous distributions of fault stress and strength are prescribed quite independently, and without a systematic relation to non-planar fault geometry. However, from a mechanical point of view, stress and strength heterogeneities and fault geometry cannot be prescribed arbitrarily. The interdependence of fault stress, strength and geometry must be consistent with a mechanical model of deformation and stress evolution over the longer time scale of the earthquake cycle. For instance, it is expected that stress concentrations can develop at the edges of asperities (defined as fault sub-regions delimited by frictional contrasts), introducing a correlation between stress and strength that enhances high frequency radiation at asperity edges. Stress concentrations are also expected near fault kinks and bends. Failure to account for such mechanical correlations leaves the dynamic rupture modeling framework so unconstrained that virtually any outcome is possible with sufficient tuning.

Therefore, to enable the generation of initial stresses for dynamic rupture models that are consistent with the distribution of fault strength and fault geometry, in this study we employ earthquake cycle modeling (e.g. Tullis 2012 and references therein, Matsu’ura 2005). Our approach involves producing earthquakes based on the rate-and-state (RS) friction law in order to examine the impact of assumed statistical characteristics of heterogeneities (e.g. Hillers et al. 2006, 2007). The earthquake cycle is modelled using a quasi-dynamic solver under the rate-and-state (RS) friction law (Dieterich 1979; Ruina 1983). Each simulation assumes a 2D distribution of the characteristic weakening distance Dc in RS friction, and depth dependent frictional parameters a and b. The dynamic rupture parameters (initial stresses, Dc, a, b and the state) extracted from the multi-cycle simulations are then used as input parameters in fully-dynamic single-event rupture modelling using SPECFEM3D (Galvez et al. 2014, 2016) with the same RS friction law. Considering seismic wave generation and propagation, fully-dynamic simulations improve the consistency of transient stress changes in front of the rupture tip, and in comparison, with quasi-dynamic cycle simulations in previous works (Hillers et al. 2007; Luo et al. 2017; Tullis 2012 and references therein) improves the accuracy of simulated models.

A single RS cycle simulation that spans several thousand years can generate multiple earthquake scenarios with spatio-temporal complexity similar to past earthquakes. A limited number of RS cycle models can thereby provide a sufficiently large database of moderate-to-large earthquakes. This dataset is used to investigate the dynamic rupture characteristics of each single event through spontaneous rupture modeling and their sensitivities to initial input models such as the critical distance, Dc. Dynamic rupture models give access to rupture properties that may be poorly resolved by source inversion, e.g. spatial correlation of high slip and high slip-rate areas, source time functions, and rupture velocities (Schmedes et al. 2010; Field 2019). Most importantly, individual events are not the result of ad hoc tuning of stress and strength heterogeneities; they are the result of the spatio-temporal evolution of the governing parameters on the frictional interface in response to steady tectonic loading.

In order to validate the results of such simulations, we seek to model events that reproduce fault slip distributions and ground motions similar to those recorded during the Mw 7.3 1992 Landers earthquake. This event occurred on a multi-segment fault system. Fault segmentation introduces complexity into the rupture process. For instance, the change of strike between fault segments enhances strong variations of stress. In fact, Oglesby and Mai (2012) show that the normal stress varies from positive (clamping) to negative (unclamping) between fault segments, which leads to unfavorable or favorable conditions, respectively for rupture growth. The spectral element method (SEM) is used here for dynamic simulations because it can handle complex fault geometries and heterogeneous media. In particular, the SPECFEM3D software for dynamic ruptures on unstructured meshes (Galvez et al. 2014) is used for this study. To allow for multi-segmented fault ruptures in the quasi-dynamic components of our earthquake cycle modelling, acceleration by a hierarchical matrix method (Bradley et al. 2014) is included.

2 Earthquake Cycles

For earthquake cycle modelling we adopt the rate-and-state friction law of Dieterich (1979) and Ruina (1983) and solve the quasi-dynamic cycle problem with a boundary element method using adaptive time stepping (QDYN, Luo et al. 2017a, 2017b, 2018). In the rate-and-state framework used in QDYN, the fault is always slipping and the shear stress “τ” remains equal to the fault strength:

where σ is the effective normal stress (Luo et al. 2018). The friction coefficient depends on the sliding velocity V and state variable “θ” by:

where the state variable is interpreted as being a measure of maturity of contacts on a fault surface (Hillers et al. 2006). \(\mu_{0}\) is the reference friction (0.6) and \(V_{o}\) the reference velocity equals to 5 mm/year. \(D_{c}\) is the characteristic weakening distance and \(a, b\) the constitutive parameters of direct and evolution effect. The state variable follows the aging law (Dieterich 1979):

The evolution of slip velocity on the fault plane is associated with the redistribution of shear stress (e.g., Hillers et al. 2006). In the quasi-dynamic limit the shear stress is related to the slip velocity by:

where \(\tau^{0}\) is the background stress, \(\eta = \frac{\mu }{{2V_{s} }}\) the seismic radiation damping, \(\mu\) the shear modulus and \(V_{s}\) the shear wave velocity. \(\tau_{i}^{r}\) is the shear stress at the i–th fault cell due to the slip on all fault cells:

where \(V_{pl}\) is the tectonic slip rate loading, \(u_{j}\) the slip at the j–th fault cell, and \(K_{ij}\) the “stiffness matrix” representing the stress on the i–th fault cell produced by unitary slip on the j–th fault cell. Analytical formulas for static stresses induced by rectangular dislocations in a homogeneous elastic half-space (Okada 1992) are used to compute the K matrix. The formulas include the free surface conditions. As our fault system is composed by 5 fault segments with variable strike (Fig. 1), it is not possible to use optimizations developed for planar faults, such as constructing K in the Fourier domain (Rice 1993) and exploiting translational invariance to compute stresses as convolutions using the Fast Fourier Transform. Instead, we accelerate our quasi-dynamic simulations by applying to K a matrix compression technique, the hierarchical matrix (H-matrix) decomposition (Othani et al. 2011; Bradley et al. 2014). The verification of our H-matrix implementation in QDYN is presented in the appendix.

a Southern California Fault system (source: http://scedc.caltech.edu/significant/Mojave.html). Bold red lines show the extended Landers fault segments considered here. The Green dots indicate the fault segment boundaries. We included the Eureka-Peak and Gravel Hills—Harper faults to reach 200 km fault length. b The 3D fault view

As the fault strength is equal to the shear stress in this modeling, we equate the time derivatives of Eqs. (1, 4):

Equations (3, 6) form a set of ordinary differential equations solved in QDYN using the adapting time-stepping Bulirsch-Stoer routine (Rubin and Ampuero 2005).

We use QDYN with H-matrix to generate seismic events. Once an earthquake is nucleated and reaches seismic slip velocities (> 0.1 m/s), QDYN exports the stresses and friction parameters to a rupture dynamic solver based on the spectral element method with rate and state friction in SPECFEM3D to properly resolve the rupture process. However, we adopt a one-way coupling approach: we do not import the outputs of SPECFEM3D into QDYN. One modeling constraint is that the dynamic solver works with a time step that is small and constant (2.5 ms). To limit the computational cost, our dynamic simulations span a time window of few hundreds of seconds. As we are interested in large events (Mw > 7) and their corresponding ground motions, we set the slip velocity threshold to a value of 0.1 m/s that guarantees the rupture of large events accelerates to seismic speeds within the limited time of the dynamic simulations. In our tests with smaller threshold values (0.005–0.01 m/s), the slow nucleation process takes more than several minutes. In the future, we will explore optimal ways to fully couple the quasi-dynamic and fully-dynamic solvers (e.g., Duru et al. 2019).

In our methodology, each event is naturally nucleated, and the time step is decreased gradually to resolve the nucleation processes. Another advantage is that the initial stresses for the dynamic rupture modelling capture the stress evolution generated by previous events. In contrast to previous single-rupture fully-dynamic modelling (e.g., Ely et al. 2010; Olsen et al. 1997) we do not apply any artificial procedure to accelerate the rupture initiation. The nucleation process starts before the slip rate reaches our prescribed threshold, but we do not expect that the details of the aseismic slip process affect aspects of the eventual rupture that are important for strong motion simulation. Overall, with this approach we aim to obtain final slip, slip velocities, rupture time and rupture velocities, similar to those observed during earthquakes.

3 Landers Fault System

It is difficult to dynamically simulate small magnitude events if the rupture tends to propagate through the whole fault without stopping. In order to avoid this problem, we consider a naturally segmented fault system having segments of different strike. For this work it is also desirable to simulate large magnitude events up to Mw 7.8, which are possible on inland faults. With these two aims in mind, we focus this study on the Landers fault system (see Fig. 1a), which hosted the Mw 7.3 1992 Landers earthquake that is used here for validation.

3.1 Geometry and Mesh

The Landers fault model used in our study is composed of 5 segments. The 1992 Mw 7.3 Landers earthquake ruptured three fault segments: the Johnson Valley Fault, the Homestead Valley Fault and the Camp Rock-Emerson fault. To extend these segments to a length of 200 km (Mw 7.8), the Eureka-Peak fault and Graves Hills-Harper fault have been added at the ends, as shown Fig. 1a. Figure 1b shows a 3D view of our fault model.

In order to mesh the complex fault system, we made use of CUBIT, a state-of-the-art hexahedral mesh generation software. The mesh and the faults used in this study are shown in Fig. 2a. Minimal Dc values available for modeling depend on the minimum mesh size. In order to allow smaller Dc values and thus smaller nucleation area and event magnitude, we refine the mesh size in the inner box containing the fault domain (see Fig. 2b). This refinement allows accurate modeling of the rupture without a large increase in demand for computer resources, while inducing only minor disturbances in the wave propagation modeling. The grid size of the refined fault elements is about 800 m. Each fault element contains 4 internal nodes, leading to an average 200 m spacing on the fault. The grid size outside the inner box increases radially in a semi-sphere of 240 km radius. The semi-sphere boundaries are set as absorbing boundaries.

a Mesh for the Extended Landers Fault. The semi-sphere radius is 240 km. The semi-sphere faces are the absorbing boundaries. The grid size increases radially outside the inner box fault domain. b The mesh in the inner box fault domain. The mesh is unstructured and has an approximate 800 m grid size. 5 interpolation nodes are used in each element, therefore the effective grid size in the inner box and the fault is about 200 meters

3.2 Friction Parameters

In order to get an event that could reproduce major features of the target 1992 Landers earthquake, it is necessary to produce a number of large magnitude ruptures, from which a target rupture could be selected. This can be done easily if the model fault produces characteristic earthquakes, as expected for mature faults. The characteristic events are considered to be those that rupture repeatedly and approximately the same fault area, and have about the same magnitude, but not necessary the same final slip distribution or rupture nucleation point.

Our goal is to generate characteristic events similar to Mw 7.3 Landers with a certain variability of seismic moment. It is computational expensive to generate realistic seismicity with a broad range of magnitudes, as it requires small grid size and large Dc variability. Therefore, we opt for a heterogeneous Dc lognormal distribution with a small standard deviation of log (Dc), “sigmalog(Dc)”, because such rather uniform Dc distribution produces seismicity dominated by characteristic large events (Mw > 7). As shown by Hillers et al. (2007, Fig. 4a, b), by increasing sigmalog(Dc), the seismicity becomes more irregular and spans a wide range of magnitudes (Mw > 5). Following these previous findings, we adopt the Dc distribution shown in Fig. 3. We consider a relatively small sigmalog(Dc) typical of mature faults. The correlation length for the Dc distribution is 2.25 km (Fig. 3, top). The mean and sigmalog(Dc) are 0.025 m and 0.25, respectively (Fig. 3, bottom).

Figure 4 shows the a-b and normal stress values as a function of depth. The region of (a-b) < 0 defines the area of velocity weakening, where both small and large events nucleate. This defines the width of the seismogenic zone, which goes from the surface down to 15 km depth, as shown in Fig. 4. Note that large ruptures may propagate into nearby regions with (a-b) > 0. The normal stress increases linearly from 0 to 6 km depth, then saturates at 120 MPa due to existence of overpressure fluids (e.g., Sibson 1992; Streit and Cox 2001). Our estimate of the saturated normal stress is larger than in Hillers et al. (2007, 50 MPa) or in Luo et al. (2017, 75 MPa) but consistent with dynamic source inversion for the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake (Urata et al. 2017, 100 MPa).

Using this fault parametrization, and thanks to the implementation of the H-matrix method, we were able to simulate multiple events along the Landers fault system. We generated about 30 events (Fig. 5) spanning the magnitude range of Mw 7.0–7.8, and nucleated on different sections of the Landers fault system.

4 Validation of Earthquake Cycle Modelling by Ground Motion Simulation

To validate earthquake source models and strong ground motion prediction methodologies, validation “in average” by comparison with ground motion prediction models (GMPE’s) is widely used (e.g. Dreger and Jordan 2014). However, data sets that are used for construction of GMPEs frequently have a shortage of near-fault records, which in turn are important for hazard assessment of critical facilities. In this study we validate earthquake cycle models by comparison of observed and simulated records and response spectra for the Mw 7.3 1992 Landers earthquake, for which many near-fault strong motion records are available.

4.1 Method of Validation

Among our 30 simulated events we selected events that satisfy the following criteria. (1) Magnitude should be nearly equal to that of the 1992 Landers earthquake, Mw 7.3. (2) The event should break the same 3 fault segments as the 1992 Landers earthquake, i.e. the Johnson Valley, the Homestead Valley and the Camp Rock-Emerson faults. (3) Rupture initiation should be close to the hypocentre of the 1992 Landers earthquake. Using these criteria, we selected two simulated events, a Mw 7.3 event at time 1245.2 years and Mw 7.31 event at time 1831.3 years. The slip distributions of the selected events are shown in Fig. 6 and compared with the multi-time-window source inversion result of Wald and Heaton (1994). Data for this figure are downloaded from the Finite-Source Rupture Model Database (http://equake-re.info/SRCMOD/). Other inversion results (e.g. Cohee and Beroza 1994, Cotton and Campillo 1995, Hernandez et al. 1999) have roughly similar slip distributions.

Procedure for selection of events for the validation. Top: slip distribution of the 1992 Landers earthquake from the source inversion by Wald and Heaton (1994). Middle and bottom: slip models of two selected simulated events occurring at times 1245.2 years and 1831.3 years. They have moment magnitude, slip distribution, rupture nucleation and ruptured segments similar to the 1992 Landers earthquake. Red circles are rupture initiation areas. Vertical dashed lines mark segment boundaries; segment names are signed in the middle plot

Recordings of the 1992 Landers earthquakes were downloaded from the Center for Engineering Strong Motion Data (https://www.strongmotioncenter.org/). Only processed records were used. A map of the selected stations is shown in Fig. 7. The sites are divided into basin and non-basin sites using the SCEC community velocity model (version 4, Lee and Chen 2016, Small et al. 2017). In order to avoid additional uncertainties related to uncertainties in the velocity model, only non-basin sites were used for validation. The recording at Lucerne was downloaded from the PEER Ground Motion Database (https://ngawest2.berkley.edu). This record has no absolute time. We aligned simulated and observed records by fitting their S-wave arrivals. A somewhat similar alignment of the S-wave was used by Wald and Heaton (1994) for this record.

Strong motion sites that recorded 1992 Landers earthquake (triangles). Color map is the surface shear wave velocity (Vs) distribution according to the SCEC community velocity model (see Lee and Chen 2016). Dark blue areas are major basins. Non-basin sites (light blue triangles) are used for validation

We simulated ground motion waveforms for the two selected events without making any modifications to their source characteristics. We used the sources generated by the dynamic models and then simulated waveforms using a separate wave propagation software. We consider only the slip rate functions in cells of the dynamic source that have slip rate larger than 0.02 m/s. Due to the large number of cells (up to 2 million for a Mw 7.3 event) we used the staggered grid 3D-FDM method of Graves (1996) instead of the discrete wavenumber method (Bouchon 1981) widely used for 1D velocity structures. The velocity model for the seismic wave propagation modelling is the 1D model used for source inversion by Wald and Heaton (1994) (see Table 1), which is a regional velocity model with an additional shallow low-velocity layer (geotechnical layer) that mimics thin alluvial layers at non-basin sites. The presence of the geotechnical layer(s) is important for simulation of short period ground motions in engineering applications; so we used a 1D velocity structure for validation, instead of the uniform half-space that was used for rupture dynamic simulation and earthquake cycle modeling.

4.2 Validation Results

The shortest period resolved by our FDM simulations was 1.0 s. The longest usable period of the observed records is 10 s. For waveform comparisons both observed and simulated waveforms were bandpass filtered in the 1–10 s period range, and then velocity response spectra Sv were calculated. Figure 8 shows simulated waveforms at non-basin sites for the second selected event (t = 1831.3 years), and comparison with observations. The first selected event (t = 1245.2 years) has roughly similar waveforms, except their first-arrival times are different due to the more northerly location of the rupture starting point.

Among 11 non-basin sites, 7 sites had good waveform fit: the amplitude, duration and predominant periods are well reproduced in the simulated waveforms. These sites are Fort Irwin, Yermo, Barstow, Lucerne, WW-Swarthout, WW-Nielson and Big Bear. Most of these sites are in the forward direction of rupture propagation, so the directivity effect is strong. Site Lucerne is the nearest recording site to the surface rupture and our reproduction of its recorded waveforms indicates that our near surface a-b settings in Fig. 4 are realistic.

At the remaining four sites, there is limited agreement between modelled and observed waveforms; only peak amplitudes are reproduced. These sites are Phelan, Joshua Tree, Silent Valley and Hemet, and most of them are located in the backward rupture direction. The recorded waveforms at these sites have a prominent long-period wave-packet, e.g. a wave after 40 s at Silent Valley in Fig. 8, having long predominant period 5.7 s, or a wave after 30 s at Joshua three, having 2.8 s predominant period. These waves may be the result of a smaller basin amplification that was not considered in the simulations (see the areas of reduced near surface velocities (Vs ~ 2.5 km/s) near sites Silent Valley and Joshua Tree in Fig. 7). Cohee and Beroza 1994 used Hemet and Silent Valley for the 1D source inversion and could not reproduce the long-period wave train on the EW component. Hemet and Silent Valley are located beside the San Jacinto Fault. It is possible that a low-velocity zone around this fault and the neighboring San Andreas Fault form a waveguide for long-period waves into the Hemet and Silent Valley sites (see discussion of Lee and Chen 2016 on their Fig. 1f). Such features are not included in our assumed velocity model.

The simulated response spectra Sv fit the data within a factor of 2 for most sites, even those that have limited waveform fit. We consider this to be a good fit for such spontaneously generated source model without any additional tuning. Average observed/synthetic spectral ratios and their standard deviations are shown in Fig. 9 for both selected events. There are no systematic discrepancies in average spectral ratios in the valid period range 2–10 s.

5 Discussion

In this study we validated multi-cycle earthquake simulations on a multi-segment fault system by comparison of modelled and observed waveform response spectra for the 1992 Landers earthquake. For more comprehensive validation, comparison of the ground motion attributes for a larger set of simulated events with GMPEs is necessary. We will do this in the near future, and anticipate some tuning of parameter settings (fault width, normal stress, etc.) may be necessary to achieve that.

Simulated events provide valuable insights on detailed features of rupture models, which have a potential impact on ground motions even though they cannot be resolved by waveform source inversions. Dynamic rupture simulations by Pulido and Dalguer (2008) and Galvez et al. (2017a, b) show that as the rupture front propagates, it encounters regions of strong asperities and once it propagates throughout the asperity, the slip increases and high slip velocities arise at the boundaries of the asperities due to the drastic change in rupture velocity. If confirmed, these features may improve strong ground motion predictions.

In our simulations Dc is the only heterogeneous model parameter. Heterogeneity of stress drop and strength excess is the spontaneous result of earthquake cycles. For this reason, correlations with Dc, the only parameter that remains unchanged throughout multiple cycles, are most important. They may allow us to extrapolate features observed in past earthquakes to future earthquakes on the same fault.

Finally, analysis of the discrepancy between short-period and long-period generation areas is also important. We will examine the scaling properties of the simulated earthquakes, with a particular focus on quantifying the distinct locations of areas of large slip and large slip velocity as a function of magnitude. The analysis will be supported by insight from the analysis of other dynamic quantities, including rupture speed, dynamic stress drop, rise time and general attributes of band-pass filtered slip velocity time histories. Our goal will be to understand the mechanical origin of the phenomenon at a sufficient level to provide a physical basis for the formulation of simplified methods to account for distinct short- and long-period slip in kinematic or pseudo-dynamic earthquake source generation algorithms for engineering ground motion prediction.

Overall, we may conclude that, after tuning the friction model so that simulated ruptures could reproduce a wide range of observed features of earthquakes, the fully dynamic multicycle methodology, developed here, is a valuable instrument for studying aspects of the earthquake rupture that cannot be directly observed nor inferred by source inversion. Except for its large computational cost, this methodology has many advantages in comparison with regular single rupture dynamic simulations, as summarized in Table 2.

6 Conclusions

A large number of events with Mw 7.0–7.8 were successfully simulated by physics-based fully-dynamic multi-cycle earthquake simulations on a model of the non-planar, multi-segment Landers fault system. Among the large number of simulated source models, two events have Mw and slip distribution similar to the 1992 Landers earthquake, and are suitable for validation. Waveform simulations for these two models lead to average response spectra and waveforms in good agreement with the recordings of the 1992 Landers earthquake.

References

Ando, R., & Kaneko, Y. (2018). Dynamic rupture simulation reproduces spontaneous multifault rupture and arrest during the 2016 Mw 7.9 Kaikoura earthquake. Geophysical Research Letters,45, 12875–12883. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL080550.

Andrews, D. J. (1976). Rupture propagation with finite stress in antiplane strain. Journal of Geophysical Research,81, 3575.

Andrews, D. J., & Ma, S. (2016). Validating a dynamic earthquake model to produce realistic ground motion. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America,106(2), 665–672. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120150251.

Bauman, C., & Dalguer, L. (2014). Evaluating the compability of dynamic rupture-based synthetic ground motion with empirical ground-motion prediction equation. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America,104(2), 634–652. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120130077.

Bouchon, M. (1981). A simple method to calculate green’s function for elastic layered media. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America,71, 959.

Bradley, A. M. (2014). Software for efficient static dislocation-traction calculations in fault simulators. Seismological Research Letters,85, 1358. https://doi.org/10.1785/0220140092.

Cohee, B. P., & Beroza, G. C. (1994). Slip distribution of the 1992 Landers earthquake and its implications for earthquake source mechanics. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America,84, 692.

Cotton, F., & Campillo, M. (1995). Frequency-domain inversion of strong motions—application to the 1992 landers earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research,100, 3961.

Dalguer, L. A., & Day, S. M. (2007). Staggered-grid split-node method for spontaneous rupture simulation. Journal of Geophysical Research,112, B02302. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004467.

Dalguer, L. A., Miyake, H., Day, S., & Irikura, J. (2008). Surface rupturing and buried dynamic-rupture models calibrated with statistical observations of past earthquakes. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America,98, 1147–1161.

Dieterich, J. H. (1979). Modeling of rock friction, 1. Experimental results and constitutive equations. Journal of Geophysical Research,84, 2161–2168.

Dreger, D. S., & Jordan, T. H. (2014). Introduction to the focus section on validation of the SCEC Broadband platform V14.3 simulation methods. Seismological Research Letters,86, 15. https://doi.org/10.1785/0220140233.

Duru, K., Allison, K.L., Rivet, M., & Dunham, E. (2019). Dynamic rupture and earthquake sequence simulations using the wave equation in second-order form. Geophysical Journal International(in review)

Ely, G. P., Day, S. M., & Minster, J. B. (2010). Dynamic rupture models for the southern San Andreas fault. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America,100(1), 131–150. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120090187.

Field, E. H. (2019). How physics-based earthquake simulators might help improve earthquake forecasts. Seismol: Research Letters. https://doi.org/10.1785/0220180299.

Gabriel, A., Ampuero, J.-P., Dalguer, L., & Mai, M. (2013). Source properties of dynamic rupture pulses with off-fault plasticity. Journal of Geophysical Research,118(8), 4117–4126. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrb.50213.

Galvez, P., Ampuero, J. P., Dalguer, L. A., Somala, S. N., & Nissen-Meyer, T. (2014). Dynamic earthquake rupture modelled with an unstructured 3D spectral element method applied to the 2011 M9 Tohoku earthquake. Geophysical Journal International,198, 1222.

Galvez, P., Dalguer, L. A., Ampuero, J. P., & Giardini, D. (2016). Rupture reactivation during the 2011 Tohoku earthquake: dynamic rupture and ground motion simulations. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America,106, 819. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120150153.

Galvez, P., Somerville, P., & Petukhin, A. (2017b). Multicycle Dynamic simulations of Inner Fault Parameters of Inland Faults, PSHA Workshop: Future Directions for Probabilistic Seismic Hazard Assessment at a Local, National and Transnational Scale. Lenzburg, Switzerland, poster B3, http://www.seismo.ethz.ch/export/sites/sedsite/research-and-teaching/.galleries/pdf_psha/Poster_Galvez.pdf. Accessed 14 Sept 2018.

Galvez, P., Somerville, P., Petukhin, A., Miyakoshi, K., Ampuero, J. P., & Luo, Y. (2017a). Characteristics of strong ground motion generation areas inferred from fully dynamic multicycle earthquake simulations. 2017 Joint Meeting of Earth and Planetary Science, Chiba, Japan, SCG70-02, https://confit.atlas.jp/guide/event/jpguagu2017/subject/SCG70-02/tables?cryptoId. Accessed 14 Sept 2018.

Graves, R. W. (1996). Simulating seismic wave propagation in 3D elastic media using staggered-grid finite differences. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America,86, 1091.

Hernandez, B., Cotton, F., & Canpillo, M. (1999). Contribution of radar interferometry to a two-step inversion of the kinematic process of the 1992 Landers earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research,104, 13083.

Hillers, G., Ben-Zion, Y., & Mai, P. M. (2006). Seismicity on a fault with rate- and state-dependent friction and spatial variations of the critical slip distance. Journal of Geophysical Research,111, 2156. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JB003859.

Hillers, G., Mai, P. M., Ben-Zion, Y., & Ampuero, J. P. (2007). Statistical properties of seismicity of fault zones at different evolutionary stages. Geophysical Journal International,169, 515.

Irikura, K., & Miyake, H. (2011). Recipe for predicting strong ground motion from crustal earthquake scenarios. Pure and Applied Geophysics,168, 85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-010-0150-9.

Lee, E.-J., & Chen, P. (2016). Improved basin structures in Southern California obtained through full-3D seismic waveform tomography (F3DT). Seismological Research Letters,87, 874. https://doi.org/10.1785/0220160013.

Luo, Y., & Ampuero, J.-P. (2018). Stability with heterogeneous friction properties and effective normal stress. Tectonophysics,733, 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2017.11.006.

Luo, Y., Ampuero, J. P., Galvez, P., Ende, M., & Idini, B. (2017a). QDYN: a Quasi-dynamic earthquake simulator (v1.1). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.322459.

Luo, Y., Ampuero, J. P., Miyakoshi, K., & Irikura, K. (2017b). Source rupture effects on earthquake moment-area scaling relations. Pure and Applied Geophysics,174, 3331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-017-1467-4.

Matsu’ura, M. (2005). Quest for predictability of geodynamic processes through computer simulation. Computing in Science and Engineering,7(4), 43.

Oglesby, D., & Mai, P. M. (2012). Fault geometry, rupture dynamics and ground motion from potential earthquakes on the north anatolian fault under the sea of Marmara. Geophysical Journal International,188, 1071. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2011.05289.x.

Ohtani, M., Hirahara, K., Takahashi, Y., Hori, T., Hyodo, M., Nakashima, H., et al. (2011). Fast computation of quasidynamic earthquake cycle simulation with hierarchical matrices. Procedia Computer Science,4, 1456.

Okada, Y. (1992). Internal deformation due to shear and tensile faults in half-space. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America,82, 1018–1040.

Olsen, K. B., Madariaga, R. J., & Archuleta, R. J. (1997). Three-dimensional dynamic simulations of the 1992 landers earthquake. Science,278, 834. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.278.5339.834.

Rice, J. R. (1993). Spatio-temporal complexity of slip on a fault. Journal of Geophysical Research,112, 9885–9907.

Ripperger, J., Ampuero, J. P., Mai, P. M., & Giardini, D. (2007). Earthquake source characteristics from dynamic rupture with constrained stochastic fault stress. Journal of Geophysical Research,112, B04311. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004515.

Ripperger, J., Mai, P. M., & Ampuero, J. P. (2008). Variability of near-field ground motion from dynamic earthquake rupture simulations. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America,98, 1207. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120070076.

Rubin, A. M., & Ampuero, J.-P. (2005). Earthquake nucleation on (aging) rate and state faults. Journal of Gephysical Research, 110, B11312.

Ruina, A. (1983). Slip instability and state variable friction laws. Journal of Geophysical Research,88, 10359–10370.

Schmedes, J., Archuleta, R. J., & Lavalle´e, D. (2010). Correlation of earthquake source parameters inferred from dynamic rupture simulations. Journal of Geophysical Research,115, B03304. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JB006689.

Shi, Z., & Day, S. (2013). Rupture dynamics and ground motion from 3-D rough-fault simulations. Journal of Geophysical Research,118, 1122–1141. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrb.50094.

Sibson, R. H. (1992). Implications of fault-valve behaviour for rupture nucleation and recurrence. Tectonophysics,211, 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1951(92)90065-E.

Small, P., Gill, D., Maechling, P. J., Taborda, R., Callaghan, S., Jordan, T. H., et al. (2017). The SCEC unified community velocity model software framework. Seismological Research Letters,88, 1539. https://doi.org/10.1785/0220170082.

Somerville, P., Irikura, K., Graves, R., Sawada, S., Wald, D., Abrahamson, N., et al. (1999). Characterizing crustal earthquake slip models for the prediction of strong ground motion. Seismological Research Letters, 70, 59–80.

Song, S. G., & Dalguer, L. A. (2013). Importance of 1-point statistics in earthquake source modeling for ground motion simulation. Geophysical Journal International,192, 1255. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggs089.

Song, S. G., Dalguer, L., & Mai, M. P. (2014). Pseudo- dynamic source modelling with 1-point and 2-point statistics of earthquake source parameters. Geophysical Journal International, 196, 1770–1786.

Streit, J. E., & Cox, S. F. (2001). Fluid pressures at hypocenters of moderate to large earthquakes. Journal of Geophysical Research,106, 2235–2243.

Trugman, D. T., & Dunham, E. (2014). A 2D Pseudodynamic rupture model generator for earthquakes on geometrically complex faults. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America,104, 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120130138.

Tullis, T. E. (2012). Preface to the focused issue on earthquake simulators. Seismological Research Letters,83, 957–958.

Ulrich, T., Gabriel, A. A., Ampuero, J. P., & Xu, W. (2019). Dynamic viability of the 2016 Mw 78 Kaikoura earthquake cascade on weak crustal faults. Nature Communications,5, 6. https://doi.org/10.31223/osf.io/aed4b.

Urata, Y., Yoshida, K., Fukuyama, E., & Kubo, H. (2017). 3-D dynamic rupture simulations of the 2016 Kumamoto, Japan, earthquake Earth. Planets and Space,69, 150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-017-0733-0.

Wald, D. J., & Heaton, T. H. (1994). Spatial and temporal distribution of slip for the 1992 landers, California, earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America,84, 668.

Wollherr, S., Gabriel, A., & Uphoff, C. (2018). Off-fault plasticity in three-dimensional dynamic rupture simulations using a modal discontinuous galerkin method on unstructured meshes: implementation, verification and application. Geophysical Journal International,214, 1556–1584. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggy213.

Acknowledgements

This study was based on the 2017 research project ‘Examination for uncertainty of strong ground motion prediction for the inland crustal earthquakes’ by the Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA), Japan. We would like to thank Dr. Andrew Bradley for providing the H-matrix module and his valuable assistance in the usage of this library. The Super Computer Shaheen II at KAUST University has been used to run the models presented in this study. Shaheen II is a Cray XC40 delivering over 7.2 Pflop/s of theoretical peak performance. Overall the system has a total of 197,568 processor cores and 790 TB of aggregate memory. J. P. A. acknowledges funding from the French government, through the UCAJEDI Investments in the Future project managed by the National Research Agency (ANR) with the reference number ANR-15-IDEX-01. Special thanks to Ueli Schindler for all his unconditional support on this work at AECOM Switzerland Office.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

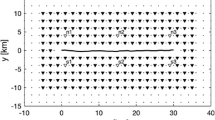

1.1 Implementation and test of the hierarchical-matrix method for earthquake cycle simulations

We implemented the Hierarchical matrix (H-matrix) method, first proposed in earthquake cycle modelling by Ohtani et al. (2011), to perform earthquake cycle modelling for the Landers fault system. The most computationally intensive part of the quasi-dynamic simulations is the matrix–vector product (MVP) K × V required at each time step to update stress rates. For N fault cells the K matrix has size (N,N) if the slip rake is fixed and only the rake-parallel component of shear stress is considered. V is a vector that contains the slip velocity at each fault cell and it has size N. In a trivial implementation, this MVP requires O(N2) operations and consumes most of the computing time. To accelerate the MVP, we implement the H-matrix method of Bradley et al. (2014) in QDYN.

The procedure to construct an H-matrix approximation of K has four parts. First, based on distance, cluster trees over mesh elements are formed. The cluster trees induce row and column permutations of K. Second, pairs of clusters are found that satisfy a criterion involving distance between the two clusters and their diameter. Third, the requested error tolerance ε is mapped to tolerances on each block Ki. The tolerance specifies the maximum error allowed. Fourth, each block is approximated by the low-rank approximation (LRA) that satisfies the block’s tolerance. While a Ki block requires O(m × n) storage, its H-matrix approximation requires only O(r(m + n)) storage.

We implemented the use of the H-matrix module “hmmvp” developed by Bradley et al. (2014) in the QDYN solver for earthquake cycle modelling in complex fault systems. This module makes use of the M approximation, which is a modification of Low-rank approximation (LRA). The M approximation allows for greater compression of the K matrix making MVP less time consuming than the LRA approximation for large N values. The hmmvp module contains C ++ routines that comprise the K matrix and a library to compute MVP. More details on this module are presented by Bradley et al. (2014). To validate our implementation, we perform earthquake cycle simulations for the planar fault shown at Fig. 10, top. This fault contains the Dc distribution for Case I (mature faults) of Galvez et al. (2017a). The model runs for a duration of about 1400 years using the FFT method of the original version of QDYN and our new implementation with the H-matrix method. The red star in Fig. 10, top represents the fault point taken as reference. As can be seen in Fig. 10, bottom, the slip velocities at the reference point obtained using the FFT and H-matrix are the same, verifying our implementation.

Verification of the H-matrix method. Top: The Dc distribution on the fault. The white star is the reference point. Bottom: Log (slip-velocity) at the reference point. The red points and the solid green line are the log (slip-velocity) computed using the FFT and H-matrix methods, respectively. The tolerance error of the H-matrix method needed to reproduce satisfactorily the FFT results is 10−8

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Galvez, P., Somerville, P., Petukhin, A. et al. Earthquake Cycle Modelling of Multi-segmented Faults: Dynamic Rupture and Ground Motion Simulation of the 1992 Mw 7.3 Landers Earthquake. Pure Appl. Geophys. 177, 2163–2179 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-019-02228-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-019-02228-x