Abstract

We investigated the constitutive parameters in the rate- and state-dependent friction (RSF) law by conducting numerical simulations, using the friction data from large-scale biaxial rock friction experiments for Indian metagabbro. The sliding surface area was 1.5 m long and 0.5 m wide, slid for 400 s under a normal stress of 1.33 MPa at a loading velocity of either 0.1 or 1.0 mm/s. During the experiments, many stick–slips were observed and those features were as follows. (1) The friction drop and recurrence time of the stick–slip events increased with cumulative slip displacement in an experiment before which the gouges on the surface were removed, but they became almost constant throughout an experiment conducted after several experiments without gouge removal. (2) The friction drop was larger and the recurrence time was shorter in the experiments with faster loading velocity. We applied a one-degree-of-freedom spring-slider model with mass to estimate the RSF parameters by fitting the stick–slip intervals and slip-weakening curves measured based on spring force and acceleration of the specimens. We developed an efficient algorithm for the numerical time integration, and we conducted forward modeling for evolution parameters (b) and the state-evolution distances (\(L_{\text{c}}\)), keeping the direct effect parameter (a) constant. We then identified the confident range of b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) values. Comparison between the results of the experiments and our simulations suggests that both b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) increase as the cumulative slip displacement increases, and b increases and \(L_{\text{c}}\) decreases as the loading velocity increases. Conventional RSF laws could not explain the large-scale friction data, and more complex state evolution laws are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

An earthquake cycle involves a very wide range of slip velocities, from orders of magnitude slower than a plate motion to as fast as a slip velocity at a rupture front during an earthquake. As earthquakes occur on a fault repeatedly, the internal structure of the shear zone and its mechanical properties are considered to evolve with increasing cumulative slip displacement (e.g., Beeler et al. 1996). The modeling of a sequence of earthquakes over the geologically long time scale probably requires a fault constitutive law which can comprehensively describe the mechanical properties of faults over the wide range of slip velocities and cumulative displacement.

The rate- and state-dependent friction (RSF) laws have been widely used to simulate earthquake sequences (e.g., Hori et al. 2004; Lapusta and Liu 2009; Noda and Lapusta 2013). These laws were originally proposed to model laboratory experimental data (Dieterich 1978, 1979; Ruina 1983), and the RSF parameters have been investigated using biaxial loading apparatuses at the low slip velocity from ~0.01 μm/s to ~1 cm/s, in which the cumulative displacement was of the order of cm at most (e.g., Mair and Marone 1999).

To achieve higher slip velocity and larger cumulative displacement, rotary shear apparatuses were developed (e.g., Tullis and Weeks 1986; Tsutsumi and Shimamoto 1997). Beeler et al. (1996) estimated the RSF parameters for large cumulative displacement at the slip velocity of 1–10 μm/s. Since a rotary shear apparatus is capable of producing high slip velocity up to a seismic rate, steady-state friction coefficients of various rock types have been investigated at a wide range of slip velocities, and a remarkable velocity-weakening property of rock friction was revealed (e.g., Di Toro et al. 2011). Although a rotary shear apparatus enables the investigation of rock friction properties with a wide range of slip velocities and large displacement as described above, the apparatus would not be suitable to investigate stick–slip behavior, which could be considered analogous to a sequence of earthquakes on natural faults (Brace and Byerlee 1966). To study the effect of cumulative displacement, it is important to consider the history of slip velocity in nature. In usual friction experiments at low slip rates, steady-state sliding of a fault is simulated, and the shear zone internal structure is developed under such circumstances. Natural fault hosting a sequence of earthquakes experiences quite different deformation conditions (e.g., repeated transients in the slip velocity with stress concentration at rupture fronts), and the resulting internal structure should be different from what is developed under steady-state sliding. Since the evolution of the internal structure causes evolution in the parameters in RSF (e.g., Beeler et al. 1996), it is important to study them in experiments with stick–slips to better understand behavior of seismogenic faults.

In addition to the limitations of the slip velocity and the cumulative displacement, conventional studies used small (on the order of 10 cm at most) rock specimens to estimate the constitutive friction parameters (e.g., Dieterich 1972; Marone and Cox 1994; Beeler et al. 1996). The constitutive friction parameters estimated for the small rock specimens may be different from those for the large rock specimens, as Yamashita et al. (2015) suggested that rock friction in meter-sized rock specimens starts to decrease at a work rate (the product of the shear stress and the slip rate) one order of magnitude smaller than that in centimeter-sized rock specimens.

Many previous studies stated above obtained the RSF parameters by the method of step changes in load point velocity. The RSF parameters can be estimated also from stick–slip behaviors (Mitchell et al. 2015). Mitchell et al. (2015) performed the inversions of experimental data for unstable sliding using a spring-slider model, but they ignored the inertia in their numerical simulations [see their Eq. (7)], which may lead to inaccurate estimation of the RSF parameters because in the quasi-static system, finite amplitude periodic oscillations are observed for very limited parameters and the slip velocity becomes infinite in unstable sliding regimes (Gu et al. 1984) where the inertia makes the slip and stress evolution completely different (Rice and Tse 1986).

In this study, we estimated the RSF constitutive parameters for the data obtained in experiment data by large-scale (on the order of meters) biaxial rock friction experiments conducted by Fukuyama et al. (2014) to investigate the dependence of the parameters on the loading velocity and cumulative displacement. For the estimation, we performed fully dynamic simulations of a single-degree-of-freedom spring-slider model. For efficient calculation, we developed a new algorithm of numerical simulations which tremendously reduces the calculation time relative to conventional methods such as embedded Runge–Kutta method.

2 Large-Scale Biaxial Rock Friction Experiments

2.1 Experimental Procedure

Fukuyama et al. (2014) constructed a large-scale biaxial friction apparatus using a large-scale shaking Table (15 m wide and 14.5 m long) at the National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Resilience (NIED) in Japan. Figure 1a shows a schematic diagram of the apparatus. A pair of rock specimens made of Indian metagabbro (see Fukuyama et al. 2016 for its mineral composition) was used. The lower specimen moved with the shaking table and the upper specimen was fixed to the outer base of the shaking table by a reaction force bar. The simulated fault between the specimens was 1.5 m long and 0.5 m wide, slid at the nominal loading velocity (\(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\)) of either 0.1 or 1.0 mm/s in a single experiment. The shaking table was instructed to move at the constant loading velocity, but the loading velocity oscillated slightly, which will be detailed in Sect. 2.2.2. The slip displacement was approx. 40 and 400 mm for experiments with \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) of 0.1 and 1.0 mm/s, respectively. The specimens were reused in a series of experiments.

a A schematic diagram and b an equivalent mechanical model of a large-scale rock friction apparatus. The spring force \(F_{\text{s1}}\) is measured by a horizontal load cell, and the normal force \(F_{\text{n}}\) is measured by three vertical load cells. The relative displacement of the sliding surfaces u is measured by two laser displacement transducers with different measurement ranges: short-range (LDT, green squares) and long-range (LDT-L, magenta squares). In this study, the LDT-L was installed on the side plate attached to the end of the lower specimen and its target was attached at the edge of the upper specimen. The LDT and its target were attached at the center of the lower and upper specimens, respectively. Acceleration (\(a_{1}\) and \(a_{2}\)) was measured in the upper and lower specimens at 20 mm from the slip interface by two accelerometers installed there (yellow circles). The table displacement l was measured by a magnetostrictive linear-position sensor installed at the bottom of the shaking table (purple squares)

Shear force on the simulated fault was produced by the movement of shaking table and was sustained by the reaction bar. The constant normal stress of 1.33 MPa was applied by three jacks and was measured using three load cells serially connected to each jack (Fig. 1a). Before the first experiment, the sliding surfaces were flattened within 0.01 mm undulation by a large-scale surface grinder. After each experiment, we sometimes removed and other times left gouge particles produced during the previous experiments. It should be noted that even when the gouge particles were not removed, detailed gouge structure might not be preserved because we have to unload the normal stress and separate two sliding surfaces at each end of the experiment due to the limitation of shaking table operation. The detailed conditions of experiments analyzed in this study are shown in Table 1.

The relative displacement of the sliding surfaces was measured by two laser displacement transducers with different measurement ranges: a long-range transducer (LDT-L) and a short-range transducer (LDT). The LDT-L was installed on the side plate attached to the end of the lower specimen, and its target was attached at the edge of the upper specimen (magenta squares in Fig. 1a). The LDT and its target were attached at the center of the lower and upper specimens, respectively (green squares in Fig. 1a). Acceleration was measured by two accelerometers installed in the upper and lower specimens at 20 mm from the slip interfaces (yellow circles in Fig. 1a). The force applied by the reaction force bar \(F_{\text{s1}}\) was measured by a load cell (Fig. 1a).

The apparatus can be considered as a coupled two-degree-of-freedom model (Fig. 1b), in the same manner that Shimamoto et al. (1980) and Noda and Shimamoto (2009) did. The force applied by the reaction force bar corresponds to the spring force of the upper spring \(F_{\text{s1}}\). The loading velocity applied by the shaking table is represented by \(v_{\text{L}}\). The equations of motion in this system are:

where m is mass of the rock specimens, a is the acceleration of the specimens, k is the spring stiffness, u is the displacement of the specimens, subscripts 1 and 2 stand for the upper and lower specimens/springs, respectively, t is time, and \(F_{t}^{{ 2 {\text{d}}}}\) is the shear force between the two specimens. It should be noted that LDT and LDT-L measured u (\(=\!\! u_{1} - u_{2}\)), and that \(F_{t}^{{ 2 {\text{d}}}}\) could not be measured directly.

2.2 Experimental Results

2.2.1 Behavior of Stick–Slips

Figures 2 and 3 show the experimental results for the friction (\(\mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime } = {{F_{\text{s1}} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{F_{\text{s1}} } {F_{\text{n}} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {F_{\text{n}} }}\)) obtained by a shear load \(F_{\text{s1}}\) divided by a normal load \(F_{\text{n}}\) (Fig. 1a). We applied a 4-kHz Butterworth-type low-pass filter to the load cell data to remove high-frequency noise. Many stick–slip events occurred during the experiments, and they had the following features.

Results of an experiment (LB01-127) that started after the removal of gouges on the sliding surface. The loading velocity \(\bar{v}_{\rm{L}}\) was 0.1 mm/s. a Time history of reaction force \(F_{\text{s1}}\) normalized by the normal force \(F_{\text{n}}\). b, c Upper and lower panels show the time histories of \({{F_{\text{s1}} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{F_{\text{s1}} } {F_{\text{n}} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {F_{\text{n}} }}\) and cumulative displacement u, respectively, for time windows b W1 and c W2 in a. The origin times of b and c correspond to 161 and 299 s in a, respectively. The red star is referred to in Fig. 5

Time history of \({{F_{\text{s1}} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{F_{\text{s1}} } {F_{\text{n}} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {F_{\text{n}} }}\) for experiments before which several experiments were conducted without gouge removal. \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) was a 0.1 mm/s (LB01-134) and b 1.0 mm/s (LB01-142). The insets in a and b show the details for time windows W3 (20 s) and W4 (3 s), respectively. The origin times of the insets in a and b correspond to 301 and 278 s in their panels, respectively

The recurrence interval (\(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\)), friction drop (\(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\)), and displacement during a stick–slip event increased with cumulative slip displacement within a single experiment (LB01-127, Fig. 2a) if gouges on the surface were removed before it. The average \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\) increased from approx. 1.5 s at short cumulative displacement (~10 mm, window W1, Fig. 2b) to approx. 3.1 s at long cumulative displacement (~24 mm, window W2, Fig. 2c). The average \(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\) increased from approx. 0.022 at short cumulative displacement to approx. 0.046 at long cumulative displacement. The slip amount during a stick–slip event increased from approx. 0.14 mm at short cumulative displacement to approx. 0.32 mm at long cumulative displacement (bottom panels in Fig. 2b, c; black solid circles in Fig. 4). In contrast, \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\) and \(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\) became almost constant throughout the experiment when the gouge particles were left on the fault prior to the experiment (Fig. 3a; blue triangles in Fig. 4).

In addition to the dependence on the cumulative slip, those characteristics of stick–slips depended on \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\); the slip amount during an event and \(\Delta \mu^{\prime}_{\text{ob}}\) were larger and \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\) was shorter for the experiments with faster \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\). The average \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\) was approx. 3.6 s for slow \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) (\(\bar{v}_{\text{L}} = 0.1{\text{ mm/s}}\), LB01-134, window W3 in Fig. 3a) and approx. 0.44 s for fast \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) (\(\bar{v}_{\text{L}} = 1.0{\text{ mm/s}}\), LB01-142, window W4 in Fig. 3b). The average \(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\) was approx. 0.052 for slow \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) (window W3) and approx. 0.060 for fast \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) (window W4). The slip amounts per event were approx. 0.35 mm for slow \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) (window W3) and 0.39 mm for fast \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) (window W4) (blue triangles and red crosses in Fig. 4).

We estimated the shear force \(F_{t}^{{ 2 {\text{d}}}}\) as a function of slip on the fault \(u_{1} - u_{2}\) during the stick–slip events. Figure 5 shows an example for the event indicated by a red star in Fig. 2c. From Eq. (1), the shear force \(F_{t}^{{ 2 {\text{d}}}}\) is

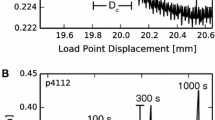

Estimation of a slip-weakening curve for the event marked by the red star in Fig. 2c. a Time history of the acceleration of the upper rock specimen \(a_{1}\). Three different low-pass filtered accelerations are shown: 1 kHz (light blue curve), 750 Hz (blue curve), and 500 Hz (black curve). b Time history of \({{F_{\text{s1}} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{F_{\text{s1}} } {F_{\text{n}} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {F_{\text{n}} }}\). c Time history of the displacement of the upper (black curve) and lower (blue curve) specimens estimated by double integration of the original acceleration waveforms. The relative displacement by acceleration (red curve) was consistent with that of the LDT (gray line). d Slip-weakening curves obtained using the acceleration data with a 1-kHz (light blue), 750-Hz (blue), and 500-Hz (black) low-pass filter applied

Following this equation, we can obtain \(F_{t}^{{ 2 {\text{d}}}}\) from the values of \(m_{1}\) calculated from rock density (2980 kg/m3) and mass volume, \(a_{1}\) measured by the accelerometer (Fig. 5a), and \(F_{\text{s1}} = - k_{1} u_{1}\) measured by the load cell (Fig. 5b).

For the estimation of \(u_{1} - u_{2}\), we conducted a double time-integration of \(a_{1} - a_{2}\) because LDT-L did not have enough resolution. Figure 5c shows a comparison of \(u_{1} - u_{2}\) obtained by the double time-integration of \(a_{1} - a_{2}\) and \(u\) measured by LDT, indicating that we can estimate the short-term slip displacement from the accelerograms. Examples of estimated slip-weakening curves are shown in Fig. 5d. In this estimation, we corrected the timing of the recording system as pointed out by Fukuyama et al. (2014). We applied a 400-Hz Butterworth-type low-pass filter to \(F_{\text{s1}}\). We examined the contribution from high-frequency waves by applying a 500-, 750-Hz, and 1-kHz low-pass Butterworth filter to the acceleration data, and we computed the slip-weakening curves (black, blue, light blue curves, respectively, in Fig. 5). Since we did not observe any significant differences in the slip-weakening curves, we confirmed that the high-frequency waves did not contribute to the estimated slip-weakening curves and used a 400-Hz cutoff. We will show the results using the acceleration data in which the 750-Hz low-pass filter was applied below.

We estimated the peak slip velocity during stick–slip events by time-integration of \(a_{1} - a_{2}\). The peak slip velocity was approx. 0.02 m/s for time window W1, 0.04 m/s for time windows W2 and W3, and 0.05 m/s for time window W4.

2.2.2 Behavior of Experimental Apparatus

Since we used a shaking table system, which was originally developed for the vibration experiments of large-scale constructions, we needed to carefully examine the behavior of the shaking table during the friction experiments. The shaking table was instructed to move at the constant loading velocity \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) (instructed loading velocity to the apparatus), but the loading velocity oscillated slightly. This is due to the delay of servo controller response of the actuator of the shaking table. As can be seen in Fig. 6, we observed that the shaking table moved faster than \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) immediately after a stick–slip event occurred. This might have been the result of dynamic overshoot of shear stress observed by the friction apparatus during a stick–slip event. The shaking table moved slightly slower than \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) just after the fast movements. Note that the total movement of the shaking table was consistent with \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}} t\) as a long time period average.

a, b Observed force (\(F_{\text{s1}}\)), laser displacement (u), table displacement (l), displacements by accelerometers (\(u_{1}\) and \(u_{2}\)) and their differences. c Observed table displacement (l) and estimated straight line (red line). a Longer time frame for \(F_{\text{s1}}\), u, and l. b Shorter time window indicated by broken square in a. Note that the stick–slip event in b is the same as that shown in Fig. 5, although the origin time for plotting was different

We estimated the fast and slow loading velocity, \(v_{\text{Lf}}\) and \(v_{\text{Ls}}\), respectively, and the duration of the fast movement, \(d_{\text{f}}\), from the observed movement of the shaking table (l), as follows. We divided each time window from W1 to W4 (Figs. 2, 3) into the shorter time windows for large and small slopes of l, and we estimated l for each time window by a straight line, as shown in Fig. 6c. The average values of the large and small slopes and the duration of the large slopes correspond to \(v_{\text{Lf}}\), \(v_{\text{Ls}}\), and \(d_{\text{f}}\), respectively. Table 2 lists the values for each time window from W1 to W4.

We estimated the stiffness \(k_{1}\) for each time window from W1 to W4. We measured the increasing rate of the spring force (\(\dot{F}_{\text{s1}}\)) during each stick from Figs. 2 and 3, and obtained \(k_{1} = {{\dot{F}_{\text{s1}} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\dot{F}_{\text{s1}} } {v_{\text{Ls}} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {v_{\text{Ls}} }}\). The average values of \(k_{1}\) for each time window were almost the same, as shown in Table 3.

The fast recovery of the friction immediately after the sharp friction drop observed at a stick–slip event would be related to the oscillation of the shaking table. This is because the ratio of \(\dot{F}_{\text{s1}}\) during the fast recovery of the friction and during stick was similar to the ratio of \(v_{\text{Lf}}\) and \(v_{\text{Ls}}\), that is, the stiffness \(k_{1}\) was almost constant through our experiments.

3 Method for Numerical Simulations

We applied a spring-slider model with mass with one-degree-of-freedom (Fig. 7) to explain the stick–slips because we found that the displacement of the lower specimen is approx. 10% of that of the upper specimen during dominant slip (16.653–16.664 s in Fig. 5c) and can be ignored. The equation of motion is

where v is the slip velocity, t is time, \(F_{\text{s}}\) is spring force, \(F_{\text{t}}\) is the shear force on the fault, and m is mass. We perform dynamic simulations (i.e., accounting for the inertial effects), in contrast to the previous studies which ignored the inertia at low slip velocity (e.g., Rice and Tse 1986; Bizzarri 2011). \(F_{\text{s}}\) is

where \(F_{0}\) is the steady-state shear force at a reference slip velocity of the friction law \(v_{0}\), k is the spring stiffness, \(v_{\text{L}}\) is the load point velocity, and u is the fault displacement. \(F_{\rm{t}}\) is assumed to obey the RSF law. We examine both Slip law (Ruina law)

and Aging law (Slowness law)

where a and b are parameters representing the direct and evolution effects, respectively, \(\theta\) is the state variable, and \(L_{\text{c}}\) is the critical slip distance (e.g., Marone 1998a). We calculated m from rock density and dimensions (Table 4). We used the estimated values of \(k_{1}\) (Table 3) as k, which was constant in our simulations because \(k_{1}\) was almost constant through the experiments, as stated in Sect. 2.2.2. The parameters used in the simulations are shown in Table 4.

If we solve Eqs. (4)–(7) for the Slip law and Eqs. (4), (5), (8), and (9) for the Aging law by the Runge–Kutta method with adaptive step-size control (Press et al. 1992), it takes too long to integrate in time domain during interseismic periods for some of the parameter sets. Therefore, we newly developed an efficient algorithm for the numerical time integration which is an example of the exponential time differencing method (e.g., Cox and Matthews 2002) similar to that used by Noda and Lapusta (2010), as described in “Appendices 1 and 2”.

We confirmed for the Slip law that the time-integration method provided results that were identical to those obtained by the Runge–Kutta method, but required only for 1/10,000 of the calculation time for \(a = 0.008\), \(b = 0.0092\), \(L_\text{c} = 0.5 \, \upmu {\text{m}}\), and the constant \(v_{\text{L}}\) of 0.1 mm/s (Fig. 18).

The loading velocity slightly fluctuated in our experiments, as stated in Sect. 2.2.2. Therefore, we assumed in our simulations that \(v_{\rm{L}}\) is the faster loading velocity \(v_{\text{Lf}}\) for the duration of \(d_{\text{f}}\) after a stick–slip event finishes and \(v_{\text{L}}\) is the slightly slower loading velocity \(v_{\text{Ls}}\) at other times. We defined that the event occurs when \(v > 10v_{\text{Ls}}\) and it finishes when \(v \le v_{\text{Ls}}\). Table 2 lists the values of \(v_{\text{Lf}}\), \(d_{\text{f}}\), and \(v_{\text{Ls}}\), which were decided from the observed movement of the shaking table (Sect. 2.2.2).

Using the new time-integration method, we conducted many numerical simulations with various combinations of the evolution parameter b and the state-evolution distance \(L_{\text{c}}\) while keeping the direct effect parameter a constant. We then estimated the combinations of b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) which reproduce the recurrence time and the friction drop consistent with \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\) and \(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\). We also calculated the slip-weakening curve with each combination, because we could not determine the optimal parameters only by the recurrence time and the friction drop as described in the next section.

4 Results

4.1 Slip Law

4.1.1 Dependence of Constitutive Parameters on Cumulative Displacement

We estimated the combinations of constitutive parameters b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) to reproduce the stick–slip events that occurred at short and long cumulative displacement in the experiment LB01-127 with \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}} = 0.1{\text{ mm/s}}\) (windows W1 and W2 in Fig. 2).

First, we modeled the observed recurrence time of the stick–slip events (\(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\)) and the observed friction drop (\(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\)). Figure 8a, b shows the computational results of the recurrence time of the stick–slip events (\(\Delta T_{\text{sy}}\)) and friction drop (\(\Delta \mu^{\prime}_{\text{sy}}\)), respectively, for various combinations of b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) values for the long cumulative displacements (window W2). The colored and gray circles indicate the parameters with which the system reached the limit cycle and the stable sliding, respectively. The crosses indicate parameters which provide the combination of plural recurrence time. The multiple recurrence time does not appear in the simulations for the constant \(v_{\text{L}}\); it comes from the changes in \(v_{\text{L}}\) in our simulations. If \(\Delta T_{\text{sy}}\) for \(v_{\text{Lf}}\) is shorter than \(d_{\text{f}}\) (duration of \(v_{\text{Lf}}\)), the stick–slip events occur during \(v_{\text{L}}\) of \(v_{\text{Ls}}\) and \(v_{\text{Lf}}\), and the multiple recurrence time arises. Our simulations are not suitable in these cases because \(v_{\text{L}}\) decreases from \(v_{\rm{Lf}}\) to \(v_{\rm {Ls}}\) after duration \(d_{\text{f}}\), whether or not a stick–slip event occurs during \(v_{\text{Lf}}\). However, we need not consider these cases because \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\) is much larger than \(d_{\text{f}}\). The diamonds show the parameter sets (b, \(L_{\text{c}}\)) that provide \(\Delta T_{\text{sy}}\) within \(\Delta \bar{T} \pm \sigma_{\text{T}}\) and \(\Delta \mu_{\text{sy}}^{\prime }\) within \(\Delta \bar{\mu }^{\prime } \pm \sigma_{\mu }\), where \(\Delta \bar{T}\) and \(\Delta \bar{\mu }^{\prime }\) are the average \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\) and \(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\) for window W2, respectively, and \(\sigma_{\text{T}}\) and \(\sigma_{\mu }\) are the standard deviation of \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\) and \(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\) for window W2, respectively. The parameter sets providing \(\Delta T_{\text{sy}}\) within \(\Delta \bar{T} \pm \sigma_{\text{T}}\) are similar to those providing \(\Delta \mu_{\text{sy}}^{\prime }\) within \(\Delta \bar{\mu }^{\prime } \pm \sigma_{\mu }\). To model \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\) and \(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\) simultaneously, we calculated the following evaluation function

as shown in Fig. 8c. The diamonds in Fig. 8c indicate the parameter sets with which \(J_{1} \le 5.99146\). If the recurrence time and the friction drop exhibit normal distributions and they are independent of each other, \(J_{1}\) follows the Chi-squared distribution with two-degrees-of-freedom, and \(J_{1} \le 5.99146\) corresponds to the 95% confidence regions. Although this assumption is inadequate because the recurrence time correlates with the friction drop, the small \(J_{1}\) indicates that \(\Delta T_{\text{sy}}\) and \(\Delta \mu_{\text{sy}}^{\prime }\) are consistent with \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\) and \(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\). That is, b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) values shown by the diamonds in Fig. 8c can reasonably reproduce \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\) and \(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\). Figure 8c shows that \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\) and \(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\) have little information on \(L_{\text{c}}\), and thus we cannot constrain the parameter set of b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) uniquely only from the recurrence time and friction drop data.

Synthetic a recurrence intervals \(\Delta T_{\text{sy}}\) and b friction drop \(\Delta \mu_{\text{sy}}^{\prime }\), and c evaluation function \(J_{1}\) plotted as a function of the constitutive parameters b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) in numerical simulations for long cumulative displacement of the LB01-127 (Fig. 2c, window W2). Gray circles show parameters with which the system reaches stable sliding. Crosses indicate parameters which provide multiple recurrence time. Diamonds in a and b show the parameters which provide \(\Delta T_{\text{sy}}\) within \(\Delta \bar{T} \pm \sigma_{\text{T}}\) and \(\Delta \mu_{\text{sy}}^{\prime }\) within \(\Delta \bar{\mu }^{\prime } \pm \sigma_{\mu }\), respectively. Diamonds in c indicate \(J_{1} \le 5.99146\)

To further constrain the possible range of \(L_{\text{c}}\), we tried to fit the slip-weakening curves (Fig. 5d). We examined the following evaluation function

for event i, where \(Nj(i)\) is the number of data for the event i, and \(\mu_{\text{sy}}\) and \(\mu_{\text{ob}}\) are the synthetic and observed shear force divided by the normal force, respectively. For this calculation, we applied the linear interpolation to the numerical result. Note that the initial friction coefficient \(\mu_{0} = {{F_{0} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{F_{0} } {F_{n} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {F_{\rm{n}} }}\) affects only the absolute level of \(\mu_{\text{sy}}\). We analyzed all of the events for window W2. Figure 9a shows the average \(\bar{J}_{2} = \sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{{N_{i} }} {J_{2} (i)/N_{i} }\), where \(N_{i}\) is the number of the events, for many computations with parameter sets (b, \(L_{\text{c}}\)). The diamonds show \(\bar{J}_{2}\) less than the minimum value of \(\bar{J}_{2} + \sigma_{\rm{J}}\) in all simulations, where \(\sigma_{\text{J}}\) is the standard deviation of \(J_{2} (i)\) for each simulation. The parameter set with small value of \(\bar{J}_{2}\) can reproduce the observed slip-weakening curves, but the parameter set with large value of \(\bar{J}_{2}\) cannot, as demonstrated in Fig. 9b.

a \(\bar{J}_{2}\) plotted as a function of the constitutive parameters b and \(L_\text{c}\) and b comparison of observed (blue circles) and synthetic (red lines) slip-weakening curves for long cumulative displacement of LB01-127 (Fig. 2c, window W2). Diamonds in a indicate \(\bar{J}_{2}\) less than the minimum value of \(\bar{J}_{2} + \sigma_{\rm{J}}\). Small letters ‘c’ and ‘e’ in a correspond to those in b. Small letter ‘c’ corresponds to the star in Fig. 10a. We plotted the observed slip-weakening curves for all of the events in window W2 (blue circles in b)

For a joint inversion of the recurrence time, the friction drop, and the slip-weakening curves, we evaluated the following function

as shown in Fig. 10a, where \({{\alpha_{1} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\alpha_{1} } {\alpha_{2} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\alpha_{2} }}\) is a weight coefficient, \(\alpha_{1}\) is the average of \(J_{1}\) in the range of \(J_{1} \le 5.99146\) (diamonds in Fig. 8c), \(\alpha_{2}\) is the average of \(\bar{J}_{2}\) less than the minimum value of \(\bar{J}_{2} + \sigma_{\rm {J}}\) (diamonds in Fig. 9a). The minimum of J (star in Fig. 10a) gives the optimum parameter set \((b , { }L_{\rm {c}} ) = (0.0094 , { }0.3 \, \upmu {\text{m}})\), and \(J \le 2\alpha_{1}\) (diamonds in Fig. 10a) can be a possible range of b and \(L_{\text{c}}\). The comparison of the observed and synthetic time histories for 20 s of displacement and of the spring force is shown in Fig. 10b, c. Our simulation could reproduce the very sharp friction drop and the subsequent fast recovery of the friction observed at a stick–slip event. These behaviors in our simulation result from the variable \(v_{\text{L}}\) (Table 2) because the features do not appear in the simulations with the constant \(v_{\text{L}}\). In addition, the synthetic recurrence time, slip amount during an event, cumulative slip for 20 s, friction drop, and the slip-weakening curves for the optimum parameter set are similar to the observations, as demonstrated in Fig. 10b, c and by the red solid line in Fig. 9b.

a J plotted as a function of the RSF parameters b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) and time history of b the cumulative displacement u and c spring force (\({{F_{{{\text{s}}1}} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{F_{{{\text{s}}1}} } {F_{\text{n}} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {F_{\text{n}} }}\) and \({{F_{\text{s}} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{F_{\text{s}} } {F_{\text{n}} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {F_{\text{n}} }}\)) for the large cumulative displacements of LB01-127 (Fig. 2c, window W2). a Star and diamonds show the optimum and the possible parameter sets, respectively. The method of the calculation of the possible range is stated in the text. b, c Blue lines show the experimental data and red lines show the synthetic data for the optimum parameter set (star in a). The observed and synthetic data are plotted by the same scales. c The initial coefficient of friction \(\mu_{0}\) is set arbitrarily for plotting

We estimated the combinations of b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) to reproduce the stick–slip events that occurred at the short cumulative slip displacement (window W1), in the same manner as at the long cumulative slip displacement (window W2). By a joint inversion of the recurrence time, the friction drop, and the slip-weakening curves (Eq. (12)), we obtained the optimum parameter set \((b, \, L_{\text{c}} ) = (0.0085, \, 0.09 \, \upmu {\text{m}})\), as shown in Fig. 11. Our simulations cannot reproduce the observed fluctuations with events of \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\), \(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\), slip amount during an event, and the slip-weakening curves, which are larger than those at the long cumulative slip displacement. However, \(\Delta T_{\text{sy}}\), \(\Delta \mu_{\text{sy}}^{\prime }\), slip amount during an event, and the slip-weakening curves for a large value of J are out of the observed fluctuations. Therefore, our estimation is reasonable.

a J plotted as a function of the RSF parameters b and \(L_\text{c}\) and b–d comparison of the observed and synthetic data for the optimum parameter set (star in a) for the small cumulative displacements of LB01-127 (Fig. 2b, window W1). a–d are drawn in the same manner as in Figs. 9b and 10, respectively

Possible parameter sets (b, \(L_{\text{c}}\)) are summarized in Fig. 12. For the short cumulative slip displacement case (window W1), \((b , { }L_{\text{c}} ) = (0.0085 , { }0.09 \, \upmu {\text{m}})\) was the best of the examined cases (i.e., J was the minimum, Fig. 11a), and the possible ranges for b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) were \(b = 0.0085\) and \(0.04 \le L_{\text{c}} \le 0.1 \, \upmu {\text{m}}\), respectively (triangles in Fig. 12). For the long cumulative slip displacement case (window W2), \((b , { }L_{\text{c}} ) = (0.0094 , { }0.3 \, \upmu {\text{m}})\) was the best (Fig. 10a), and the possible ranges of b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) were \(0.0092 \le b \le 0.0096\) and \(0.04 \le L_{\text{c}} \le 0.8 \, \upmu {\text{m}}\), respectively (circles in Fig. 12).

Parameter sets that provided stick–slip behaviors consistent with the experimental data in cases with the Slip law. Triangles and circles show the parameter sets for small and large cumulative displacement, respectively (slip dependence, Sect. 4.1.1). Squares show the rate-dependence (Sect. 4.1.2). Open and solid symbols correspond to \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) of 0.1 and 1.0 mm/s, respectively. Red symbols indicate the parameter sets with which J is the minimum

These results suggest that the evolution-related constitutive parameters (b and \(L_{\text{c}}\)) increased as the cumulative displacement increased, even in a single experiment. By comparing the triangles and the circles in Fig. 12, we can say that the b value is significantly different. The \(L_{\text{c}}\) value might be different between these two time windows, but the error range was too large to judge the differences.

We compared \(\Delta T_{\text{sy}}\) at limit cycles with \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\) not at limit cycles. The synthetic stick–slips reach a limit cycle after several stick–slips in the simulations with the possible parameters. However, the observed stick–slips did not reach a limit cycle even after many stick–slips occurred. Therefore, other processes such as changes in the state of the fault surfaces may have occurred in the experiment, which were not taken into account in synthetic model. This will be discussed in Sect. 5.

4.1.2 Dependence of Constitutive Parameters on Loading Velocity

We estimated the constitutive parameters b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) to reproduce the stick–slip events observed in experiments LB01-134 with the slow \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) (\(\bar{v}_{\text{L}} = 0.1{\text{ mm/s}}\)) and LB01-142 with the fast \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) (\(\bar{v}_{\text{L}} = 1.0{\text{ mm/s}}\)) (Fig. 3). Throughout each of these experiments, \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\) and \(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\) were almost constant (blue triangles and red crosses in Fig. 4). We estimated the constitutive parameters b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) in the same manner as that described in Sect. 4.1.1. Figures 13 and 14 show the results of the joint inversion of the recurrence time, the friction drop, and the slip-weakening curves for the slow and fast \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\), respectively. The observed fluctuations of \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\), \(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\), and the slip-weakening curves with events are smaller than those in LB01-127 (Sect. 4.1.1), and thus the synthetic slip-weakening curves fitted the observations better and we constrained the \(L_{\text{c}}\) value better.

For the case of the slow \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\), the best parameter set was \((b , { }L_\text{c} ) = (0.0098 , { }0. 9 { }\,\,\upmu {\text{m}})\), and the possible b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) values were \(0.0097 \le b \le 0.0098\) and \(0.7 \le L_{\text{c}} \le 1.0\,\, \upmu {\text{m}}\), respectively (open squares in Fig. 12). For the case of the fast \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\), the best parameter set was \((b , { }L_{\text{c}} ) = (0.0103 , { 0} . 1 \,\,{ }\upmu {\text{m}})\), and the possible b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) values were \(0.0103 \le b \le 0.0105\) and \(0.09 \le L_{\text{c}} \le 0.2 \, \upmu {\text{m}}\), respectively (solid squares in Fig. 12). Therefore, the constitutive parameters show clear dependence on \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\); b increases and \(L_{\text{c}}\) decreases as \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) increases. By comparing the open and solid squares in Fig. 12, we can say that the b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) values are significantly different.

4.2 Aging Law

We examined the Aging law, in the same manner as in Sect. 4.1 for the Slip law. The estimated constitutive parameters b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) and the possible ranges are summarized in Fig. 15. The results for the short and long cumulative displacements (triangles and circles in Fig. 15) suggest that the evolution-related constitutive parameters (b and \(L_{\text{c}}\)) increase as the cumulative displacement increases in a single experiment. The b value is significantly different. The \(L_{\text{c}}\) value can be different between these two time windows, but the error range was too large to judge the differences. The comparison of the results for the slow and fast \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) (open and solid squares) suggest that b increases and \(L_{\text{c}}\) decreases as \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) increases and that the b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) values are significantly different.

Parameter sets which provide stick–slip behaviors consistent with the experimental data in cases with the Aging law. This figure is drawn in the same manner as Fig. 12

The values of the evaluation functions \(J_{1}\), \(J_{2}\), and J (Eqs. (10)–(12)) for the estimated parameter sets were slightly different between the Slip and Aging laws, but we did not see any superiority of one over the other (Table 5). The b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) values estimated for the Aging law are smaller than for the Slip law (Fig. 12) in all of the examined cases (windows from W1 to W4). However, our results for the Aging law stated above are the same as for the Slip law in Sect. 4.1.

5 Discussion

The results of this study suggest that when a friction experiment starts without gouges on the fault, both the b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) values increase as the cumulative slip increases, as stated in Sect. 4.1.1. Beeler et al. (1996) also reported the decrease in \(a - b\) in some initially bare surface experiments. On the other hand, Leeman et al. (2016) suggested that decreases in both \(a - b\) and \(L_{\text{c}}\) with the cumulative slip. They constructed 3-mm-thick layers of powdered silica to simulate granular fault gauges, which might cause the contradiction between their results and ours on \(L_{\text{c}}\). Our results on the slip dependence of the RSF parameters can be partly explained by the production of gouges, since the state-evolution distance \(L_{\text{c}}\) increases with increasing gouge layer thickness as suggested by Marone and Kilgore (1993). In fact, many gouge particles were produced during the present friction experiments as described by Fukuyama et al. (2014). From the estimated gouge production rate, we calculated 5.013 × 10−7 and 1.303 × 10−6 m as averaged thicknesses of the gouge layers for W1 and W2 in LB01-127, respectively. See “Appendix 3” for detail of this estimation. Note that we estimated these thicknesses assuming that the produced gouge materials are uniformly distributed over the fault surface. Actually, the gouge materials were locally produced in and around the generated grooves as revealed by Yamashita et al. (2015). Therefore, these thicknesses could be minimum estimates. The estimated b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) values were larger in experiment LB01-134 (open squares in Figs. 12, 15) than in experiment LB01-127 (triangles and circles in Figs. 12, 15), which is consistent with the slip dependence described in Sect. 4.1.1, because LB01-134 was conducted after several experiments following LB01-127 without the removal of gouges. The conventional RSF laws with a single set of the RSF parameters were not sufficient to explain the results of the long cumulative displacement experiments, and more complex state evolution laws accounting for gouge production are needed to comprehensively describe the large-scale experimental data.

It is important to note that most earthquake cycle simulations (e.g., Hori et al. 2004; Lapusta and Liu 2009; Noda and Lapusta 2013) used the conventional RSF law with a single state-variable. Based on the present findings, however, the evolution of friction as a function of slip during evolution of the internal structure of the shear zone (e.g., accumulation of wear material) could not be well expressed by the conventional RSF law. To account for the large-scale behavior in which the apparent RSF parameters evolve with changes in the internal structures of the shear zone, a different framework is required.

We found an increase in b as \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) increased, as stated in Sect. 4.1.2. This indicates a positive correlation between \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) and the friction drop. Some previous studies, however, suggested that the friction drops of the stick–slip events decreased with the increase of the loading velocity (Karner and Marone 2000; Mair et al. 2002; Anthony and Marone 2005; McLaskey et al. 2012). The negative correlation between \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) and the friction drop shown by the previous studies can be interpreted to result from contact aging associated with frictional healing during the inter-seismic period of the seismic cycle. Our results do not deny the effect of the frictional healing because peak friction was slightly higher at lower \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) in our experiments as shown in Fig. 3. Instead, our results may suggest that the velocity-weakening effect is stronger than that expected from the conventional RSF law with a single set of the RSF parameters. The estimated peak slip velocity was approx. 0.02–0.05 m/s and higher for the faster \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) in our experiments (Sect. 2.2.1). In this velocity range, friction weakens as a function of slip velocity (e.g., Di Toro et al. 2011); therefore, larger friction drop would occur for higher slip velocity. Kato et al. (1991) obtained similar data in experiments with a granite specimen as well as a composite specimen of granite and marble. The correlation between the friction drop and the loading velocity might relate to the characteristics of the apparatus used in the experiments.

The estimated \(L_{\text{c}}\) values except for time window W3 are smaller than those obtained by the previous studies (0.7 μm or longer, e.g., Dieterich 1979; Marone et al. 1990). The small \(L_{\text{c}}\) could result from the thin gouge layer. As described above, Marone and Kilgore (1993) proposed a scaling relation that \(L_{\text{c}}\) is proportional to the gouge thickness. The gouge layer thicknesses estimated in this study are two orders of magnitude smaller than those in the previous experiments (e.g., Marone et al. 1990; Marone and Kilgore 1993); therefore, \(L_{\text{c}}\) could be smaller in our experiments than in the previous studies. The small \(L_{\text{c}}\) might be also related to the velocity weakening processes. This is because the previous studies obtained \(L_{\text{c}}\) by velocity step change tests, while we obtained \(L_{\text{c}}\) from stick–slips which involve high slip velocity (0.05 m/s at most).

Unstable (seismic) slip may occur for spring stiffness smaller than a critical value, as theoretically shown by Ruina (1983). Leeman et al. (2016) showed that the behaviors of stick–slips and stable sliding are related to normalized critical stiffness \(\kappa = {k \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {k {k_{\text{c}} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {k_{\text{c}} }}\) where \(k\) is loading system stiffness, \(k_{\text{c}} = {{\sigma_{\rm{n}} \left( {b - a} \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\sigma_{n} \left( {b - a} \right)} {L_{\rm{c}} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {L_{\text{c}} }}\) is critical stiffness of a fault, and \(\sigma_{\text{n}}\) is the normal stress. From the stiffness and the RSF parameters obtained in Sects. 2.2.2 and 4, we estimated \(\kappa\) as shown in Table 3. Many stick–slip events were observed for \(\kappa \ll 1\), which are consistent with Leeman et al. (2016) and the theoretical works (e.g., Ruina 1983). However, stick–slip behaviors cannot be explained only by \(\kappa\) in our experiments. For example, \(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\) of stick–slip events and slip amount per event were high in the order of W4, W3, W2, and W1, but \(\kappa\) was small in the different order.

We assumed that a value is constant since a is considered as the material property. However, a might depend on temperature change (e.g., Blanpied et al. 1995; Nakatani 2001) and on the loading velocity because Marone (1998b) showed that the static friction increases with the loading rate (1–10 μm/s) by double-direct shear experiments. To investigate the dependency of a on the estimation of b and \(L_{\text{c}}\), we conducted the same computation using \(a = 0.005\) and \(a = 0.011\) for window W2. We estimated the constitutive parameters (b, \(L_{\text{c}}\)) and their possible ranges, in the same manner as in Sect. 4.1.1, summarized in Fig. 16. The estimated \(L_{\text{c}}\) values were slightly different among the examined cases. On the other hand, the estimated \(b - a\) values increased as a values decrease because \(\Delta T_{\text{sy}}\) and \(\Delta \mu_{\text{sy}}^{\prime }\) depended on not only b value but also a value. The values of the evaluation functions \(J_{1}\), \(J_{2}\), and J (Eqs. (10)–(12)) for the estimated parameter sets were similar in the cases with different a values, as shown in Table 6. This means that the optimum parameter set (a, b, \(L_{\text{c}}\)) cannot be determined uniquely. Thus, the \(L_{\text{c}}\) values estimated in Sect. 4 do not depend on the choice of a value, but the dependence of b values on the cumulative displacement and on \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) could be explained by the dependence of a values.

Optimum parameters (red symbols) and possible ranges for long cumulative displacement in experiment LB01-127 (window W2) for various a values. Gray, open, and black circles show the possible ranges when a is equal to 0.005, 0.008, and 0.011, respectively. Open circles are the same as those in Fig. 12

Fukuyama et al. (2014) observed that a stick–slip event was initiated by the nucleation of a dynamic rupture, which propagated on the simulated fault surface. In this study, we used a one-degree-of-freedom spring-slider model (Fig. 7) and did not take into account the finiteness of the slip area. The minimum nucleation size for the Aging law for anti-plane strain,

where G is the shear modulus and \(\nu\) is the Poisson’s ratio, was estimated by Ampuero and Rubin (2008). G and \(\nu\) for Indian metagabbro used in our experiments are 39.3 and 0.31 GPa, respectively. From the parameters obtained in Sect. 4.2, \(L_{\text{b}}\) is estimated to be 0.31, 0.48, 2.8, and 0.36 m for windows W1 (short cumulative slip displacement), W2 (long cumulative slip displacement), W3 (slow \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\)), and W4 (fast \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\)), respectively. The increase in \(L_{\text{b}}\) for windows from W1 to W3 could represent the gouge production. The \(L_{\text{b}}\) values are smaller than the sample size, except for window W3; therefore, a rupture can propagate dynamically as a stick–slip event. It matters whether or not the sample size is larger than the nucleation size, and the effect of dynamic rupture propagation on the overall friction deserves future experimental and theoretical investigation.

There is evidence that the stick–slip behavior may be related to the damage of sliding surface as described below. Unfortunately, in the series LB01 presented here, we did not conduct the stick–slip experiment at the beginning. However, we observed the dependence of the stick–slip behavior on the slip surface damage in the LB09 series, in which the width of the lower rock specimen was reduced to 0.1 m to increase the normal stress to 6.7 MPa. The rock was Indian metagabbro, same as in the present experiments described above. The fault surface was repeatedly slid for 900 s at \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) of 0.01 mm/s, and the gouges were removed after each experiment. We compared the stick–slip behaviors at the same time window (600–700 s) to avoid the effect of cumulative slips from gouge removal.

We found that \(\Delta T_{\text{ob}}\) and \(\Delta \mu_{\text{ob}}^{\prime }\) were small in the first experiment of the LB09 series (Fig. 17a), whereas both became larger and almost constant in subsequent experiments (Fig. 17b). These observations support the idea that the friction drops and the recurrence time depend on the damage on the fault surface in addition to \(\bar{v}_{\text{L}}\) and the cumulative displacement demonstrated in this paper. The effects of the damage on the fault surface will be further investigated in future works.

Time history of \({{F_{{{\text{s}}1}} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{F_{{{\text{s}}1}} } {F_{\text{n}} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {F_{\text{n}} }}\) a for the first experiment with the rock specimens whose surfaces were prepared using a surface grinder and never used in any experiments (LB09-001) and b for the second experiment with the same specimens under the same conditions (LB09-002). Note that the gouges produced in the first experiment were removed before the second experiment

6 Conclusions

We estimated the constitutive parameters in the RSF law (for both Slip and Aging laws) by fitting numerical simulations to stick–slip experiments with a large-scale biaxial rock friction apparatus at the NIED. During the friction experiments, many stick–slip events were observed, and their features are summarized as follows. (1) The friction drop and recurrence time of the stick–slip events increased with cumulative displacement within a single experiment when gouges were removed before the experiment. (2) The friction drop and recurrence time became more or less constant throughout the experiment when the experiment was done after several experiments without removing gouges. (3) The friction drop became lager and the recurrence time was shorter for an experiment with faster loading velocity. We estimated the slip-weakening curves during the stick–slip events from measured spring force and the accelerations of the specimens. We applied a one-degree-of-freedom spring-slider model with mass to explain the observed stick–slips. We developed an efficient algorithm for numerical time integration, and we conducted many numerical simulations with various b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) values while keeping a constant. We then identified the values of b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) that provided a consistent recurrence time, friction drops, and slip-weakening curves during the stick–slip events.

The results of our analyses suggest that (1) both b and \(L_{\text{c}}\) increase as the cumulative displacement increases, and (2) b increases and \(L_{\text{c}}\) decreases as the loading velocity increases, for both Slip and Aging laws. Therefore, the conventional RSF laws with an invariable single set of the RSF parameters cannot explain the whole of the experimental data. More complex state evolution laws are needed to comprehensively describe the experimental data and to consider an earthquake cycle involving a wide range of slip velocities and a sequence of earthquakes over geologically long times during which the evolution of the internal structure of the shear zone is significant.

References

Ampuero, J.-P., & Rubin, A. M. (2008). Earthquake nucleation on rate and state faults—aging and slip laws. Journal of Geophysical Research, 113, B01302. doi:10.1029/2007JB005082.

Anthony, J. L., & Marone, C. (2005). Influence of particle characteristics on granular friction. Journal of Geophysical Research, 110, B08409. doi:10.1029/2004JB003399.

Beeler, N. M., Tullis, T. E., Blanpied, M. L., & Weeks, J. D. (1996). Frictional behavior of large displacement experimental faults. Journal of Geophysical Research, 101(B4), 8697–8715. doi:10.1029/96JB00411.

Bizzarri, A. (2011). Temperature variations of constitutive parameters can significantly affect the fault dynamics. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 306, 272–278.

Blanpied, M. L., Lockner, D. A., & Byerlee, J. D. (1995). Frictional slip of granite at hydrothermal conditions. Journal of Geophysical Research, 100(B7), 13045–13064. doi:10.1029/95JB00862.

Brace, W. F., & Byerlee, J. D. (1966). Stick–slip as a mechanism for earthquakes. Science, 153(3739), 990–992. doi:10.1126/science.153.3739.990.

Cox, S. M., & Matthews, P. C. (2002). Exponential time differencing for stiff systems. Journal of Computational Physics, 176(2), 430–455. doi:10.1006/jcph.2002.6995.

Di Toro, G., Han, R., Hirose, T., De Paola, N., Nielsen, S., Mizoguchi, K., et al. (2011). Fault lubrication during earthquakes. Nature, 471, 494–498. doi:10.1038/nature09838.

Dieterich, J. H. (1972). Time-dependent friction in rocks. Journal of Geophysical Research, 77(20), 3690–3697. doi:10.1029/JB077i020p03690.

Dieterich, J. H. (1978). Time-dependent friction and the mechanics of stick–slip. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 116(4–5), 790–806. doi:10.1007/BF00876539.

Dieterich, J. H. (1979). Modeling of rock friction: 1. Experimental results and constitutive equations. Journal of Geophysical Research, 84(B5), 2161–2168. doi:10.1029/JB084iB05p02161.

Fukuyama, E., Yamashita, F., & Mizoguchi, K. (2016). Voids and rock friction at subseismic slip velocity. Journal of Geophysical Research (under Rev).

Fukuyama, E., et al. (2014). Large-scale biaxial friction experiments using a NIED large-scale shaking table—design of apparatus and preliminary results—. Report of the National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Prevention, 81, 15–35.

Gu, J.-C., Rice, J. R., Ruina, A. L., & Tse, S. T. (1984). Slip motion and stability of a single degree of freedom elastic system with rate and state dependent friction. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 32(3), 167–196. doi:10.1016/0022-5096(84)90007-3.

Hori, T., Kato, N., Hirahara, K., Baba, T., & Kaneda, Y. (2004). A numerical simulation of earthquake cycles along the Nankai Trough in southwest Japan: Lateral variation in frictional property due to the slab geometry controls the nucleation position. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 228, 215–226. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2004.09.033.

Karner, S. L., & Marone, C. (2000). Effects of loading rate and normal stress on stress drop and stick–slip recurrence interval. In J. B. Rundle, D. L. Turcotte, & W. Klein (Eds.), Geocomplexity and the Physics of Earthquakes (pp. 187–198). Washington, D. C.: American Geophysical Union.

Kato, N., Kusunose, K., Yamamoto, K., & Hirasawa, T. (1991). Slowly propagating slip events in a composite sample of granite and marble. Journal of Physics of the Earth, 39(2), 461–476.

Lapusta, N., & Liu, Y. (2009). Three-dimensional boundary integral modeling of spontaneous earthquake sequences and aseismic slip. Journal of Geophysical Research, 114, B09303. doi:10.1029/2008JB005934.

Leeman, J. R., Saffer, D. M., Scuderi, M. M., & Marone, C. (2016). Laboratory observations of slow earthquakes and the spectrum of tectonic fault slip modes. Nature Communications, 7, 11104. doi:10.1038/ncomms11104.

Mair, K., Frye, K. M., & Marone, C. (2002). Influence of grain characteristics on the friction of granular shear zones. Journal of Geophysical Research, 107(B10), 2219. doi:10.1029/2001JB000516.

Mair, K., & Marone, C. (1999). Friction of simulated fault gouge for a wide range of velocities and normal stresses. Journal of Geophysical Research, 104(B12), 28899. doi:10.1029/1999JB900279.

Marone, C. (1998a). Laboratory-derived friction laws and their application to seismic faulting. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 26, 643–696. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.26.1.643.

Marone, C. (1998b). The effect of loading rate on static friction and the rate of fault healing during the earthquake cycle. Nature,. doi:10.1038/34157.

Marone, C., & Cox, S. J. D. (1994). Scaling of rock friction constitutive parameters—the effects of surface-roughness and cumulative offset on friction of gabbro. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 143(1–3), 359–385. doi:10.1007/BF00874335.

Marone, C., & Kilgore, B. (1993). Scaling of the critical slip distance for seismic faulting with shear strain in fault zones. Nature, 362, 618–621. doi:10.1038/362618a0.

Marone, C., Raleigh, C. B., & Scholz, C. H. (1990). Frictional behavior and constitutive modeling of simulated fault gouge. Journal of Geophysical Research, 95(B5), 7007–7025.

McLaskey, G. C., Thomas, A. M., Glaser, S. D., & Nadeau, R. M. (2012). Fault healing promotes high-frequency earthquakes in laboratory experiments and on natural faults. Nature, 491, 101–104. doi:10.1038/nature11512.

Mitchell, E. K., Fialko, Y., & Brown, K. M. (2015). Frictional properties of gabbro at conditions corresponding to slow slip events in subduction zones. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 16(11), 4006–4020. doi:10.1002/2015GC006093.

Nakatani, M. (2001). Conceptual and physical clarification of rate and state friction: Frictional sliding as a thermally activated rheology. Journal of Geophysical Research, 106(B7), 13347–13380. doi:10.1029/2000JB900453.

Noda, H., & Lapusta, N. (2010). Three-dimensional earthquake sequence simulations with evolving temperature and pore pressure due to shear heating: Effect of heterogeneous hydraulic diffusivity. Journal of Geophysical Research, 115, B12314. doi:10.1029/2010JB007780.

Noda, H., & Lapusta, N. (2013). Stable creeping fault segments can become destructive as a result of dynamic weakening. Nature, 493, 518–521. doi:10.1038/nature11703.

Noda, H., & Shimamoto, T. (2009). Constitutive properties of clayey fault gouge from the Hanaore fault zone, southwest Japan. Journal of Geophysical Research, 114, B04409. doi:10.1029/2008JB005683.

Press, W. H., Flannery, B. P., Teukolsky, S. A., & Vetterling, W. T. (1992). Numerical recipes (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rice, J. R., & Tse, S. T. (1986). Dynamic motion of a single degree of freedom system following a rate and state dependent friction law. Journal of Geophysical Research, 91(B1), 521–530. doi:10.1029/JB091iB01p00521.

Ruina, A. (1983). Slip instability and state variable friction laws. Journal of Geophysical Research, 88(B12), 10359–10370. doi:10.1029/JB088iB12p10359.

Shimamoto, T., Handin, J., & Logan, J. M. (1980). Specimen-apparatus interaction during stick–slip in a tri axial compression machine: A decoupled two-degree-of-freedom model. Tectonophysics, 67, 175–205.

Tsutsumi, A., & Shimamoto, T. (1997). High-velocity frictional properties of gabbro. Geophysical Research Letters, 24(6), 699–702. doi:10.1029/97GL00503.

Tullis, T. E., & Weeks, J. D. (1986). Constitutive behavior and stability of frictional sliding of granite. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 124(3), 383–414. doi:10.1007/BF00877209.

Yamashita, F., Fukuyama, E., Mizoguchi, K., Takizawa, S., Xu, S., & Kawakata, H. (2015). Scale dependence of rock friction at high work rate. Nature, 528(7581), 254–257. doi:10.1038/nature16138.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the NIED research project entitled ‘Development of Earthquake Activity Monitoring and Forecasting’ and the JSPS KAKENHI, Grant No. 23340131. Assistance for the experiments provided by Tetsuhiro Togo, Hironori Kawakata, Nana Yoshimitsu, Tadashi Mikoshiba, Makoto Sato, Chikahiro Misawa, Toshiyuki Kanezawa, Hiroshi Kurokawa, Toya Sato, and Toshihiko Shimamoto is greatly appreciated. Anonymous reviewers’ comments were quite valuable in improving our manuscript. Friction experiment data are available upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Exponential Time Differencing Method for the SLIP Law

1.1 Governing Equations

A spring-slider system with one-degree-of-freedom consists of Eqs. (4)–(7) in the main text:

where dots on the top represent derivatives with respect to time t, \(A = aF_{\text{n}}\) and \(B = bF_{\text{n}}\) are parameters representing the direct and evolution effects, respectively, and the definitions of the other characters are the same as those in the main text. The time-derivative of Eq. (16) is:

Now we normalize these equations by introducing nondimensional parameters. The slip rate shall be normalized by the steady-state velocity:

The nondimensional time shall be defined as:

The nondimensional frictional stress difference from the steady-state is:

and the nondimensional spring force difference from the steady-state is:

The nondimensional state variable is:

The nondimensional equations then take the form of:

where primes represent derivatives with respect to the nondimensional time. The parameters in the nondimensional equations are:

D represents the significance of the direct effect with respect to the inertia, \(\kappa_{1}\) is the nondimensional spring constant, and C represents the significance of spring stiffness with respect to inertia. Note that \(C^{{{1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 2}} \right. \kern-0pt} 2}}}\) is proportional to the natural angular frequency of the harmonic oscillator.

There are four Eqs. (24)–(27), but we have one constraint from the friction law:

Therefore, the system is a three-dimensional ordinary differential equation. Since Eq. (32) describes the relation between w, g, and \(\varPsi\), we have only to integrate Eq. (25) and additional two equations among Eqs. (24), (26), and (27).

1.2 Exponential Time Differencing Method

By integrating Eqs. (25)–(27) with (32), we obtained the following second-order accurate (in terms of \(\tau_{1}\)) expressions at \(\tau_{1}\), supposing we have \(h_{0}\), \(g_{0}\), and \(\varPsi_{0}\) at \(\tau = 0\):

where

Note that \(g_{{{\text{ss}}0}}\) and \(\varPsi_{{{\text{ss}}0}}\) are (pseudo-)steady-state values which would be achieved if \(g\) and \(\varPsi\) were only variables in Eqs. (26) and (27), respectively. \(\tau_{\text{g}}\) and \(\tau_{\Psi }\) are decay time constants. Then we can estimate \(w\) at \(\tau_{1}\) as:

Adopting those starred values leads to a first-order integration scheme, but we can iterate this scheme to increase the order of accuracy (see Noda and Lapusta 2010). In the second-order scheme, we integrate the first half time-step using values at \(\tau = 0\):

and then the latter half using the starred values estimated above

where

We then estimate w at \(\tau_{1}\) as:

1.3 Variable Time Step for the Exponential Time Differencing Method

To decrease the calculation time, we use variable time steps determined by the following equation:

The time interval is \(\Delta \tau_{\hbox{max} }\) when the slip rate of the block v is very small. When v is nearly \(v_{\hbox{max} }\), the time interval is smaller than the time interval \(\Delta \tau_{\text{cnst}}\) for appropriate calculations with the constant time interval. We set \(\Delta \tau_{\hbox{max} } = 0.01\), \(\Delta \tau_{\text{cnst}} = 10^{ - 5}\), and \(v_{\hbox{max} } = 0.05{\text{ m/s}}\), which is consistent with the maximum slip rate in the large-scale experiments. Note that the slip increment for a time step is a fixed fraction of \(L_{\text{c}}\) because \(\tau\) is equal to \({{v_{0} t} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{v_{0} t} {L_{\text{c}} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {L_{\text{c}} }}\) and \(\Delta \tau\) is inversely proportional to v.

1.4 Comparison with the Runge–Kutta Method

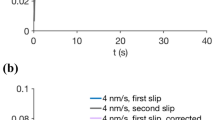

The parameters of an example problem are \(v_{\text{L}} = 0.1{\text{ mm/s}}\), \(b = 0.0092\), and \(L_{\text{c}} = 0.5 \, \upmu {\text{m}}\). Simulations were carried out until \(t = 20{\text{ s}}\). Figure 18 shows the stick–slip behaviors obtained by the Runge–Kutta method and our exponential time differencing method. They are almost identical; our numerical method works properly. The calculation time necessary for our method was approx. 1/10,000 of that needed to use the Runge–Kutta method.

Comparison of stick–slip behaviors obtained by the Runge–Kutta method (black curves) and our exponential time differencing method (red curves). a Changes in the friction coefficient \({{\left( {F_{\text{t}} - F_{0} } \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\left( {F_{\text{t}} - F_{0} } \right)} {F_{\text{n}} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {F_{\text{n}} }}\) as a function of slip velocity. b Time history of slip velocity for a stick–slip event

Appendix 2: Exponential Time Differencing Method for the AGING Law

We developed the same method for the Aging law as for the Slip law. The definitions of the characters in the following equations are the same as those in “Appendix 1”. We also used the same variable time step stated in “Appendix 1.3”.

2.1 Governing Equations

A spring-slider system with one-degree-of-freedom consists of Eqs. (4), (5), (8), and (9) in the main text:

where the definitions of the other characters are the same as those in “Appendix 1” and the main text. The time-derivative of Eq. (56) is:

Now we normalize these equations by introducing nondimensional parameters. Nondimensional slip rate, time, frictional stress difference from the steady-state, and spring force difference from the steady-state shall be defined as Eqs. (19)–(22). The nondimensional state variable is:

The nondimensional equations then take the form of Eqs. (24), (25) and

The parameters in the nondimensional equations, \(\beta\), D, C, and E, are Eqs. (28)–(31).

There are four Eqs. (24), (25), (60) and (61), but we have one constraint from the friction law:

Therefore, the system is a three-dimensional ordinary differential equation. Since Eq. (62) describes the relation between w, g, and \(\varPsi\), we have only to integrate Eq. (25) and additional two equations among Eqs. (24), (60), and (61).

2.2 Exponential Time Differencing Method

By integrating Eqs. (25), (60), (61) with (62), we obtained the second-order accurate (in terms of \(\tau_{1}\)) Eqs. (33)–(35), where \(\tau_{\text{g0}}\) and \(\tau_{\Psi 0}\) are Eqs. (38) and (40), respectively, and

Note that \(g_{\text{ss0}}\) and \(\varPsi_{\text{ss0}}\) are steady-state values which would be achieved if only \(g\) and \(\varPsi\) were variables in Eqs. (60) and (61), respectively. \(\tau_{\text{g}}\) and \(\tau_{\Psi }\) are decay time constants. Then we can estimate \(w\) at \(\tau_{1}\) as:

Adopting those starred values leads to a first-order integration scheme, but we can iterate this scheme to increase the order of accuracy (see Noda and Lapusta 2010). In the second-order scheme, we integrate the first half time-step using values at \(\tau = 0\), Eqs. (42)–(44), and then the latter half using the starred values estimated above, Eqs. (45)–(47), where \(\tau_{\rm{g1}}^{*}\) and \(\tau_{\Psi 1}^{*}\) are Eqs. (48) and (50), respectively, and

We then estimate w at \(\tau_{1}\) as:

Appendix 3: Estimation of Gouge Production Rate

To evaluate effect of the increasing gouge layer thickness, we estimated the gouge production rate from the volume of collected gouge material and amount of mechanical works done during the experiments. Mass of the gouge materials collected after the experiment LB01-111 was 12.0009 g. This gouge was produced by four frictional experiments, LB01-104, -106, -108, and -111. See Fukuyama et al. (2014) for the details of the experimental conditions. From the measured mass, we estimated the volume of the produced gouge material to be 6.330 × 10−6 m3 under the assumption that effective density of the gouge material of metagabbro is equal to 1896 kg/m3 following Yamashita et al. (2015). Total amount of mechanical works was calculated as 1.086 × 105 J from \(F_{\text{s1}}\) integrated over the entire slip distances in the four experiments. As the result, we estimated the gouge production rate to be 5.828 × 10−11 m3/J.

From this estimated rate, we can calculate the averaged thicknesses of the gouge layer for W1 and W2 in LB01-127 as 5.013 × 10−7 and 1.303 × 10−6 m, respectively. Note that we estimated these thicknesses assuming the produced gouge materials are uniformly distributed over the fault surface. Actually, the gouge material was locally produced in and around the generated grooves as revealed by Yamashita et al. (2015). Therefore, these thicknesses could be minimum estimates.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Urata, Y., Yamashita, F., Fukuyama, E. et al. Apparent Dependence of Rate- and State-Dependent Friction Parameters on Loading Velocity and Cumulative Displacement Inferred from Large-Scale Biaxial Friction Experiments. Pure Appl. Geophys. 174, 2217–2237 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-016-1422-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-016-1422-9