Abstract

The Pomerania region (northwest part of Poland) occupies a significant position, where the largest European tectonic boundary is situated. This is the area of the contact between the East European Craton (EEC) and the Paleozoic Platform (PP) and it is known as the Trans-European Suture Zone (TESZ). The TESZ was formed during Paleozoic time as a consequence of the collision of several crustal units and it extends from the Black Sea in the southeast to the British Isles in the northwest. It is a region of key importance for our understanding of the tectonic history of Europe. Previous magnetotelluric (MT) results, based on 2-D inverse modeling, show that the contact zone is of lithospheric discontinuity character and there are distinct differences in geoelectric structures between the Precambrian EEC, transitional zone (TESZ), and the younger PP. The presence of a significant conductor at mid and lower crustal depths was also shown. Thus, the main aim of the research presented here was to obtain detailed, 3-D images of electrical conductivity in the crust and upper mantle and its regional distribution below the TESZ in the northwest part of Poland. To accomplish this task we applied the latest 3-D inversion codes, which allowed us to get more realistic model geometries. Additionally, to confirm and complement the study, the Horizontal Magnetic Tensor (HMT) analysis was realized. This method gives us an opportunity to efficiently locate the position of well-conducting structures. As a result we obtain a clearer, three-dimensional model of conductivity distribution, where highly conductive rock complexes appear which we tentatively connected to deformation fronts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction and Geological Background

In the Cambrian, the microcontinent Avalonia broke off from Gondwana and at the end of the Ordovician it collided with the Baltica continent. Afterwards, the combined Baltica and Avalonia collided progressively with Laurentia forming the Laurussia continent. This collision caused a mountain building era named the Caledonian orogeny. The Permo-Carboniferous collision of the continents Gondwana, Laurussia, and Baltica, termed the Variscan orogeny, molded the late Paleozoic supercontinent of Pangaea. Nowadays, the placement and mutual positions of Variscan Deformation Fronts (VDF) and Caledonian Deformation Fronts (CDF) are still a subject of discussion. Figure 1 shows a tectonic map of Central Europe.

In Central Europe the most noteworthy and important boundary between the main geotectonic units is the so-called Teisseyre-Tornquist Zone (TTZ). The TTZ is a broad fault zone and part of the Trans-European Suture Zone (TESZ) which separates the Proterozoic East European Craton (EEC) from the Paleozoic Platform (PP). The TESZ is covered by thick Permian–Cenozoic sedimentary layers along almost its entire length. The Permian sediments are represented by thick Upper Permian–Zechstein evaporites (salt and anhydrite) and carbonates (Plein 1990; Scheck and Bayer 1999). The Post-Permian differentiation was governed by a couple of phases of Mesozoic tectonic activity, including Triassic extensional events and Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous extension/transtension, e.g., (Dadlez 2003). Accordingly, those and later tectonic phases of the movements of Zechstein salt redounded to sedimentation and the subsequent deformation of Mesozoic and Cenozoic structures. As a result the present-day Central European part of the TESZ has been filled by a wide variety of salt structures (walls, diapirs and pillows). The total sedimentary thickness ranges from about 4−8 km in the EEC to 8–15 km in the TTZ and the PP. A well-conducting, saline aquifer is characteristic for the study area; it extends throughout the entire North German–Polish Basin.

The study region has been an object of intensive seismic investigations. For the area considered in this paper several seismic profiles were conducted (Guterch et al. 1994; Janik et al. 2002). The seismic survey sees low-velocity rocks with low velocity gradients and velocity contrasts at seismic boundaries (0.3–0.5 km/s) in the upper crust of the TESZ, whereas the lower crust is characterized by a high velocity gradient and strong ringing reflectivity, indicating a distinctly laminar seismic structure (Janik et al. 2002).

It this paper, we analyze two methods based on electromagnetic (EM) soundings and provide information on electrical resistivity distribution in the Earth. Previous results together with new data will be discussed in more detail and the application of recent 3-D inversion codes allows us to obtain more realistic model geometries as before.

2 Methods

Earlier magnetotelluric (MT) and magnetovariational (MV) transects across the Polish Basin have provided many data concerning the structure of lithosphere. They were interpreted in a two-dimensional manner (Ernst et al. 2008; Habibian et al. 2010; Schäfer et al. 2011). This was certainly justified for most of the data besides the central part of the profiles, where significant 3-D behavior appears.

During the previous EMTESZ (electro-magnetic sounding of Trans European Suture Zone) project, 2-D resistivity models for two profiles (termed LT-7 and P2) were obtained. One of the major achievements of the project was to document the presence of northwest striking, well-conductive rock complexes. Beneath the central part of both profiles a conductive structure was deduced which reaches a minimum resistivity of about 2 \(\Omega\)m and lies at a depth of 10–20 km. The values of electrical conductivity obtained from the previous models, where integral conductivity locally exceeds 10,000 S, are attributed to the occurrence of sedimentary rocks. But it is still not possible to unequivocally establish either these are porous rocks filled with mineralized water, or rocks containing metals or graphite such as black or alum shales. 2-D models as shown by Ernst et al. (2008) and Habibian et al. (2010) can only be regarded as a first step and need to be improved by taking 3-D effects into account.

2.1 MT and MV Transfer Functions

Variations of the external geomagnetic field induce electric currents in the Earth, which direction and intensity depend on the electrical conductivity distribution of geological structures. Electromagnetic (EM) sounding methods either measure these currents directly or their respective secondary magnetic field and thus provide information on the electrical state of the crust or even the upper mantle. The variants magnetotellurics (MT) and magnetovariational (MV) sounding are routinely applied either individually or together to study the electrical conductivity structure of the Earth. MT comprises the determination of transfer functions between natural horizontal electric and magnetic field variations (impedance), on the other hand in MV transfer functions (tippers, vectors, magnetic tensors) between magnetic field components at spatially distributed sites are estimated.

Various transfer functions are determined:

-

1.

In the magnetotelluric method the relationship between horizontal components of the electric (E) and magnetic (H) fields defines the impedance tensor \(\mathbf {Z}\):

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} E_x \\ E_y \end{bmatrix}=\left[ \begin{array}{cc} Z_{xx} &{} Z_{xy}\\ Z_{yx} &{} Z_{yy} \end{array}\right] \begin{bmatrix} H_x \\ H_y \end{bmatrix}. \end{aligned}$$(1)The impedance is usually converted and displayed as a pair of real parameters: the apparent resistivity

$$\begin{aligned} \rho _{a\, i,j}=\frac{1}{\mu \omega } |Z_{i,j}|^2, \quad i,j\in \{x,y\} \end{aligned}$$(2)and the impedance phase

$$\begin{aligned} \varphi _{i,j}=arg(Z_{i,j}), \quad i,j\in \{x,y\}, \end{aligned}$$(3)where \(\omega\) is the angular frequency and \(\mu\) is the magnetic permeability.

-

2.

If the vertical magnetic field is recorded as well, the ratio of vertical to horizontal magnetic field components is also indicative of the electrical structure of the Earth and termed tipper \(\mathbf {T}\):

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} H_z \end{bmatrix}=\left[ \begin{array}{cc} {T_x},&{T_x} \end{array}\right] \begin{bmatrix} H_x \\ H_y \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned}$$(4)This transfer function is conventionally displayed as real and imaginary induction vectors \(\mathbf {C_u}\) and \(\mathbf {C_v}\):

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf {C_u}=\left[ \begin{array}{cc} Re\,\quad {T_x} \\ Re\,\quad {T_y} \end{array}\right] , \,\,\, \mathbf {C_v} =\left[ \begin{array}{cc} Im\,\quad {T_x} \\ Im \,\quad {T_y} \end{array}\right] \end{aligned}$$(5) -

3.

The magnetovariational transfer function between horizontal magnetic fields of a local and another distant (reference) is the so-called horizontal magnetic tensor (HMT):

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} H_x (p) \\ H_y(p) \end{bmatrix}=\mathbf {M}(p,p_\text{r}) \begin{bmatrix} H_x (p_\text{r}) \\ H_y(p_\text{r}) \end{bmatrix}. \end{aligned}$$(6)

Here p denotes a local observation point and \(p_\text{r}\) a reference site (e.g., Schmucker 1070; Berdichevsky and Dmitriev 2008). All above equations have been formulated in Cartesian coordinates, where the x-axis points towards north, y-axis points to east and z-axis points vertically inward.

These functions introduced here depend on location, Earth’s structure and frequency. They are routinely applied either individually or in some combination to study the electrical conductivity (or resistivity) of the Earth.

Between 2004 and 2013, new long-period soundings (T = 10–10,000 s) were carried out in Northwest Poland. Figure 2 shows those sites which are relevant for this study. Figure 3 displays two exemplary sites. Site Air represents good data quality while data at site Lys are of poorer quality (particularly the main diagonal of the impedance tensor) which was caused by near direct current (DC) railways and commuter trains. Robust remote-reference (RR) analysis was routinely applied by employing the scheme of Egbert and Booker (1986).

Distribution of MT sites and major DC railway lines in NW Poland. Red triangles represent stations from the previous EMTESZ project (LT-7 profile), green triangles mark sites which were used for this study and include recently collected data. Data for sites Air and Lys are shown below, more data are displayed in the electronic supplement

Example of apparent resistivity \(\rho _\text{a}\) and phase \(\varphi\) curves (two upper rows) as functions of period. Site Air represents good data quality and it is located in the northern part of the mesh, while site Lys is located in the southern part, near one of the main Polish railway lines and represents rather bad data quality. Continuous line complies with response after inversion. Below induction vectors \(\mathbf {C_u}\) and \(\mathbf {C_v}\). Green color represents the response after inversion

Dimensionality and strike analysis employing the phase tensor method of Caldwell et al. (2004) yields an essentially three-dimensional subsurface beneath the TESZ. Figure 4 shows phase tensor ellipses and inductions vectors for each site of the array for four different periods. One can easily notice that the orientation of the vectors varies strongly with period. The color code refers to skew angle \(\beta\), which is significantly large (\(|\beta |\) >5°) for all periods, thus indicating more 3-D structure. Especially for the central part of the study area, change in orientation of the phase tensor ellipses is conspicuous. Neither in southernmost nor northern stations the phase tensor ellipses vary that strongly.

2.2 HMT Image of NW Poland

Afterwards the horizontal magnetic tensor (HMT) was analyzed. Application of the HMT method is a very informative way of tracing complexes of conductive rocks. This is because the greatest singular value of HMT (HMT invariant) reaches its maximum value above such structures (Jozwiak 2012). In a traditional approach to calculate the HMT, it is necessary to have synchronous recordings but a lastly developed algorithm (Nowożyński 2012) allowed us to determine the HMT from the magnetovariation data (tippers) collected at different times with different reference stations.

The magnetic field components are linked in two ways. The relationship (4) allows us to calculate the vertical component from the horizontal components, whereas, via the Hilbert transform, we are able to obtain the horizontal components from the vertical component. These dependencies generate a system of linear equations with which we are able to reconstruct the magnetic field components on the Earth’s surface. The Hilbert transform is determined using a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) thereupon the tippers have to be approximated on a rectangular grid. To achieve this, two-dimensional splines approximation of separated unknowns is used (Nowożyński 2012).

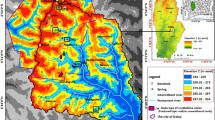

The method presented above is very helpful and facilitates to determine HMT in regions where the data set (tippers) is sufficiently dense. This is important since the induction vectors are calculated from field recording in one site and it is possible to systematically complement the data for areas of interest, and to use the ample archival set of such values existing throughout Poland. Furthermore, the obtained HMT values are not contaminated by the effect of various inhomogeneities in the vicinity of the reference station, since the results produced by the reconstruction procedure is equivalent to those for the reference station placed in infinity. The new method for the period of 1800 s was used for reference purposes. The result is shown in Fig. 5.

Spatial distribution of the most informative invariants (the largest singular value) of the HMT for NW part of Poland, calculated for the period of 1800 s. White dots mark MT sites used in this paper. Red color shows the locations of conducting structures. Gray lines indicate the hypothetical locations of the Variscan Deformation Front (VDF) and the Caledonian Deformation Front (CDF)

On the enlarged map, elongated regions of distinctly greater values of the HMT invariant (red color) are visible. The position of these large-scale conducting structures correlates quite well with the hypothetical range of the Caledonian and Variscan Deformation Fronts.

3 3-D Inverse Modeling

The parallel version of the ModEM package of Egbert and Kelbert (2012) was used for inversion. ModEM is an electromagnetic inverse modeling program written in FORTRAN 95 and based on a standard minimum-structure, non-linear conjugate gradients algorithm (NLCG). We used a parallel implementation (Meqbel 2009) on a Linux cluster with the standard message passing interface (MPI). Additionally to the full impedance tensor, the ModEM algorithm allows to invert the magnetic transfer function (tipper).

For the 3-D inversion 31 MT stations and 12 periods (four periods per decade) were used. The mesh was located in the northwest part of Poland, over a surface area (central part) of approximately 125 km × 125 km (Figs. 1, 5). The total grid size was 70 × 70 × 43, in x, y, and z directions, where the central part of the model held 52 × 52 cells (on the Earth’s surface). The full mesh extended over 1300 km in x and y and 600 km in z directions. The initial model was set to a background resistivity of 100 \(\Omega\)m (a homogeneous half-space). The initial model mesh was created by the MtTF software, developed at the IGF PAN by co-author of this paper, Nowożyński.

For the inverse modeling several attempts were made. In the beginning, the first tries consisted in choosing appropriate values for the model covariance. These parameters are responsible for the smoothing between any two model areas and might be defined for x, y and z directions separately. Our testing was started with covariances of 0.3 for all directions and turned out much too small (conductive area occurred only in a few first layers). Afterwards, the value was increased up to 0.7. In the end, to obtain the best resolution for the whole model we decided to modify the model covariance continuously from 0.7 to 0.5 for x and y directions and 0.7 for z direction. In addition to experimenting with covariances, we also modified the homogeneous halfspace of the initial model and included a well-conducting layer near the surface, which represents the saline aquifer encountered throughout the North German–Polish Basin. This layer was already resolved in previous studies (Ernst et al. 2008; Habibian et al. 2010; Schäfer et al. 2011).

After 188 iterations the final normalized root mean square (RMS) misfit was 1.86 (with 7.5 % error floor for impedance and 1.5 % for tippers). An example of data fit of the apparent resistivities, phases and tippers has been already shown in Fig. 3; the responses at all sites may be found in the electronic supplement. The resulting model of electrical resistivity is shown in Figs. 6, 7 and 8 in the following section.

4 Results

A high-resistivity basement can be separated here by the East European Craton (D) and the block of the Paleozoic Platform (C). The contact zone between the platforms is visible on our model (F). Below the conductive sedimentary cover (A), there is a non-conductive layer of Zechstein salt. The more resistive Czaplinek block marks here by well developed non-piercing salt domes of NW–SE trend (Fig. 6).

Plan view of the model at depths of 5, 10, 21 and 50 km. The letters B, B′ and F denote the same geological structures as in Fig. 6

Comparison of 2-D and 3-D models along LT-7 profile. a 2-D resistivity model obtained from inversion of TE and TM together with tipper and horizontal magnetic data for the LT-7 profile [modified from Habibian et al. 2010]. The blue square indicates the zone for 3-D interpretation. b Resistivity cross section along the central profile. Note, that horizontal exaggeration (HE) is about 1.5. The letters B, B′ and F denote the same geological structures as in Figs. 6 and 7

The WSW–ENE striking conductive complex (B) and related with it slightly more resistive structures (Figs. 7, 8b) one can see at a depth of 10–30 km (B). They are extending towards the west and located in a position of the Variscan Deformation Front (VDF) which is postulated by geologists (Narkiewicz and Dadlez 2008). These are probably foredeeps in front of mountain chains formed as a result of the orogenic movement.

The integrated conductivity reaches 10,000 S at 20–30 km depths. It is difficult to decide on the mechanism of such conductivity but they are likely metamorphosed sedimentary rocks. It was identified on the basis of a data analysis of seismic refraction as a Pre-Variscan consolidated crust (Dadlez 2006) and was characterized to low values of P wave velocity (5.85 km/s). Those rocks can contain metal sulfides or graphite, as well as they can be fractured rocks filled by mineral water.

In the north, the CDF is also seen at the margin of our 3-D model (B′) and in all probability a main part of it lies outside the soundings area, where we do not have data. Because of this we are not able to estimate its thickness and extent. However, the structure B′ seems to be much more shallow than the structures of VDF.

The resulting 3-D model generally confirms some of the major crustal conductive anomalies observed in the 2-D model of Habibian et al. (2010), which comprised joint inversion of impedance, tipper and inter-station magnetic transfer functions. The anomaly (A), (F) as well as the anomaly (B′) are distinct in both approaches (2-D and 3-D), whereas the anomaly B appears only in the models of 3-D inversions. This could be caused by 3-D character of these structures (see Fig. 4). Obviously, data affected by such 3-D structures cannot be rightly interpreted by 2-D algorithms. In this sense, the 3-D model is more realistic than the 2-D models.

Nevertheless, the presence of the anomaly F (Figs. 6, 7, 8) turned out to be the most surprising result of our inversion. As distinct from B and B′, its direction is close to the meridian. It is difficult to conclude about the genesis of this anomaly since in the literature there has been no notification of its existence so far.

To test the significance of structure F we carried out a sensitivity analysis by replacing the low resistivities with the “normal” resistivity of 100 \(\Omega\)m. An overall RMS analysis of respective stations was carried out and the station Low was chosen because here the misfit was bad, and the site is situated close to the removed anomaly. The table of RMS analysis of respective stations is presented in the electronic supplement. In Fig. 9 is shown the comparison between the original data from site Low and the result obtained from 3-D inversion (solid line) and forward modeling of the modified model (dotted line). The triangles mark the original data, a dotted line marks a forward modeling result, and points mark the final result. The difference between these two results proves very well that the structure has a influence for the 3-D inversion.

Perhaps, the only clue is to analyze the distribution of Pre-Zechstein faults (Krzywiec 2006). One can see that anomaly (F) is relatively close to one of the Pre-Zechstein faults (red, dashed line in Fig. 10). The position of the fault (F) is slightly shifted towards the northeast direction. Location of this fault zone was determined in the top of the Sub-Zechstein basement at a depth of about 5 km. However, it is a very approximate location because it is based on uncertain seismic reflection data (the salt complexes cause a very effective screening for reflection seismics), and it assumes an analysis of the process of forming the salt domes observed in the subsurface layers. In our model, the conductive structure (F) is much deeper and is slightly inclined. Therefore, these two structures are most likely associated with the same tectonic processes, and subsequently they have been mutually moved.

Comparison of the result obtain from the 3-D inversion drawn on a map of hypothetical fault zone within the Pre-Zechstein basement location. The result is shown for the horizontal plan for 12 km. The letters: B, B′ and F correspond to the main geological structures Variscan Front, Caledonian Front, and Pre-Zechstein fault (after Krzywiec et al. 2006; Krzywiec 2006). Note that the color scale is slightly different than for previous figures

In the next step, the obtained models have been compared to the results of the HMT analysis. Figure 5 shows the overall distribution of crustal conductivity anomalies in Poland and adjacent areas. The high values (red color) show the locations of conducting structures. The conductive areas correlate to structures (B) and (B′) very well. In all probability, we are dealing with the same zones. Note, however, that the exact position and depth of both deformation fronts and fault zones do not have any surface expression and are just inferred from other geophysical data which may suffer from resolution problems in this deep basin.

5 Discussion

The investigation area is located in the TESZ, the most pronounced geologic zone in Europe north of the Alpine. It marks the border between Proterozoic and Phanerozoic Europe with Variscan, Caledonian and Alpine orogenic elements (Berthelsen 1998). The structure of the Earth’s crust is characterized by sedimentary sequences that extend down to the top of Zechstein and older sedimentary rocks. Our results show two separate regions, EEC and PP, and the conductive lineament between and related to the TESZ. The model developed by us explains our MT soundings much better compared with previous interpretations in 2-D. It reflects the heterogeneity of the sedimentary cover very well and is compatible with other geological and borehole data. Nevertheless, the most important result of 3-D inverse modeling is the structure of the crust under the non-conductive layer of the Zechstein.

The obtained distribution of conductivity shows that the previously described conductive anomalies have much more complicated internal structure. Furthermore, the existence of a previously unknown conductive structure of meridional direction in the center of the study area has been established at a depth of 10–20 km.

In accordance with previous suggestions that anomalies (B) and (B′) might be a result of tectonic movements, appropriate Variscan and Caledonian and later, as a result of intense tectonic processes taking place in the area that they could be moved and also torn. The geometry of the conductive structures determined by us will be very useful in describing the nature of these processes.

References

Berdichevsky, M., & Dmitriev, V. (2008). Models and Methods of Magnetotellurics. Springer-Verlag, Berlin-Heidelberg.

Berthelsen, A. (1998). The Tornquist Zone northwest of the Carpathians: an intraplate pseudosuture. Geol. Foren. Stockh. Forh., 120, 223–230.

Caldwell, T., Bibby, H., & Brown, C. (2004). The magnetotelluric phase tensor. Geophys. J. Int., 158, 457-469. doi:10.1029/2007GL034610

Dadlez, R. (2003). Mesozoic thickness pattern in the mid-polish trough. Geol. Quart., 47, 223-240.

Dadlez, R. (2006). The Polish Basin-relationship between the crystalline, consolidated and sedimentary crust. Geol. Quart., 50 (1), 43–58.

Egbert, G., & Booker, J. (1986). Robust estimation of geomagnetic transfer functions. Geophys. J. R. astr. Soc., 87, 173–194.

Egbert, G., & Kelbert, A. (2012). Computational recipes for electromagnetic inverse problems.Geophys. J. Int., 189. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2011.05347.x

Ernst, T., Brasse, H., Cerv, V., Hoffmann, N., Jankowski, J., Jozwiak, W., Kreutzmann, A., Neska, A., Palshin, N., Pedersen L. B., Smirnov, M., Sokolova, E., & Varentsov, I. M. (2008). Electromagnetic images of the deep structure of the Trans-European Suture Zone beneath Polish Pomerania. Geophys. Res. Lett., 35. doi:10.1029/2007GL034610

Guterch, A., Grad, M., Janik, T., Materzok, R., Luosto, U., Yliniemi, J., . . . Förste, K. (1994). Crustal structure of the transition zone between Precambrian and Variscan Europe from new seismic data along LT7 profile (NW Poland and eastern Germany). C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, ser.II, 319, 1489–1496.

Habibian, B., Brasse, H., Oskooi, B., Ernst, T., I., E. S., Varentsov, & EMTESZ Working Group. (2010). The conductivity structure across the Trans-European Suture Zone from magnetotelluric and magnetovariational data modeling.Phys. Earth Planet. Inter., 183. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2012.05458.x

Janik, T., Yliniemi, J., Grad, M., Thybo, H., Tiira, T., & Group, P. (2002). Crustal structure across the TESZ along POLONAISE’97 seismic profile P2 in NW Poland.Tectonophysics, 360, 129–152.

Jozwiak, W. (2012). Large-Scale Crustal Conductivity Pattern in Central Europe and Its Correlation to Deep Tectonic Structures. Pure Appl. Geophys., 169, 1737–1747. doi:10.1007/s00024-011-0435-7

Krzywiec, P. (2006). Triassic-jurassic evolution of the NW (Pomeranian) segment of the Mid-Polish Trough - basement tectonics vs. sedimentary patterns.Geol. Quart., 51, 139–150.

Krzywiec, P., Wybraniec, S., & Petecki, Z. (2006). Budowa tektoniczna podłoża bruzdy śródpolskiej w oparciu o wyniki analizy danych sejsmiki refleksyjnej oraz grawimetrii i magnetyki. [W:] Krzywiec P. & Jarosiński M. (red.) Struktura litosfery w centralnej i północnej Polsce - obszar projektu POLONAISE’97.Pr. Państw. Inst. Geol., 188, 107–130.

Meqbel, N. (2009). The electrical conductivity structure of the dead sea basin derived from 2D and 3D inversion of magnetotelluric data. PhD thesis, Free Univ. Berlin.

Narkiewicz, M., & Dadlez, R. (2008). Geological regional subdivision of poland: general guidelines and proposed schemes of sub-Cenozoic and sub-Permian units.Prz. Geol., 56, 391–397. doi:in Polish with English abstract

Nowożyński, K. (2012). Splines in the approximation of geomagnetic fields and their transforms at the Earth’s surface. Geophys. J. Int., 189 (3), 1369–1382. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2012.05458.x

Plein, E. (1990). The southern Permian Basin and its Paleogeography. In: Heling, D., Rothe, P., Förstner, U., Staffers, P. (Eds.), Sediments and Environmental Geochemistry - Selected Aspects and Case Histories. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, 124–133.

Scheck, M., & Bayer, U. (1999). Evolution of the Northeast German Basin inferences from a 3D structural model and subsidence analysis. Tectonophysics, 313 , 145–169.

Schäfer, A., Houpt, L., Brasse, H., Hoffmann, N., & EMTESZ Working Group. (2011). The North German Conductivity Anomaly revisited.Geophys. J. Int., 187. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2011.05145.x

Schmucker, U. (1970). Anomalies of geomagnetic variations in the southwestern United States. Univ. of California Press, Berkeley.

Acknowledgments

This work has been funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Poland (Grants: NCN 2011/01/B/ST10/07046 and NCN 2011/01/B/ST10/07305) and German Science Foundation (Grant: BR1351/9-1). The authors thank David Martens (FU Berlin) for providing his plotting routines. Finally, we thank the editor and two reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ślęzak, K., Jóźwiak, W., Nowożyński, K. et al. 3-D Inversion of MT Data for Imaging Deformation Fronts in NW Poland. Pure Appl. Geophys. 173, 2423–2434 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-016-1275-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-016-1275-2