Abstract

We construct a bi-Hamiltonian structure for the holomorphic spin Sutherland hierarchy based on collective spin variables. The construction relies on Poisson reduction of a bi-Hamiltonian structure on the holomorphic cotangent bundle of \(\mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})\), which itself arises from the canonical symplectic structure and the Poisson structure of the Heisenberg double of the standard \(\mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})\) Poisson–Lie group. The previously obtained bi-Hamiltonian structures of the hyperbolic and trigonometric real forms are recovered on real slices of the holomorphic spin Sutherland model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The theory of integrable systems is an interesting field of mathematics motivated by influential examples of exactly solvable models of theoretical physics. For reviews, see, for example, [4, 5, 22, 25]. There exist several approaches to integrability. One of the most popular ones in connection with classical integrable systems is the bi-Hamiltonian method, which originates from the work of Magri [18] on the KdV equation, and plays an important role in generalizations of this infinite-dimensional bi-Hamiltonian system [8]. As can be seen in the reviews, among finite-dimensional integrable systems the central position is occupied by Toda models and the models that carry the names of Calogero, Moser, Sutherland, Ruijsenaars and Schneider. The Toda models have a relatively well-developed bi-Hamiltonian description [25]. The Calogero–Moser-type models and their generalizations are much less explored from this point of view, except for the rational Calogero–Moser model [2, 7, 11]. In our recent work [12, 13], we made a step towards improving this situation by providing a bi-Hamiltonian interpretation for a family of spin extended hyperbolic and trigonometric Sutherland models. In these references, we investigated real-analytic Hamiltonian systems and here wish to extend the pertinent results to the corresponding complex holomorphic case.

Specifically, the aim of this paper is to derive a bi-Hamiltonian description for the hierarchy of holomorphic evolution equations of the form

where Q is an invertible complex diagonal matrix of size \(n\times n\), L is an arbitrary \(n\times n\) complex matrix, and the subscript 0 means diagonal part. The eigenvalues \(Q_j\) of Q are required to be distinct, ensuring that the formula

gives a well-defined linear operator on the off-diagonal subspace of \(\mathrm{gl}(n,\mathbb {C})\). By definition, \({{\mathcal {R}}}(Q)\in \mathrm {End}(\mathrm{gl}(n,\mathbb {C}))\) vanishes on the diagonal matrices, and one can recognize it as the basic dynamical r-matrix [6, 9]. Like in the real case [12], it follows from the classical dynamical Yang–Baxter equation satisfied by \({{\mathcal {R}}}(Q)\) that the evolutional derivations (1.1) pairwise commute if they act on such ‘observables’ f(Q, L) that are invariant with respect to conjugations of L by invertible diagonal matrices.

The system (1.1) has a well-known interpretation as a holomorphic Hamiltonian system [17]. This arises from the parametrization

where p is an arbitrary diagonal and \(\phi \) is an arbitrary off-diagonal matrix. The diagonal entries \(p_j\) of p and \(q_j\) in \(Q_j = e^{q_j}\) form canonically conjugate pairs. The vanishing of the diagonal part of \(\phi \) represents a constraint on the linear Poisson space \(\mathrm{gl}(n,\mathbb {C})\), and this is responsible for the gauge transformations acting on L as conjugations by diagonal matrices. The \(k=1\) member of the hierarchy (1.1) is governed by the standard spin Sutherland Hamiltonian

For this reason, we may refer to (1.1) as the holomorphic spin Sutherland hierarchy.

It is also known (see, for example, [21]) that the holomorphic spin Sutherland hierarchy is a reduction of a natural integrable system on the cotangent bundle \(\mathfrak {M}:=T^* \mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})\) equipped with its canonical symplectic form. Before reduction, the elements of \(\mathfrak {M}\) can be represented by pairs (g, L), where g belongs to the configuration space and \((g,L) \mapsto L\) is the moment map for left-translations. The Hamiltonians \(\mathrm {tr}(L^k)\) generate an integrable system on \(\mathfrak {M}\), which reduces to the spin Sutherland system by keeping only the observables that are invariant under simultaneous conjugations of g and L by arbitrary elements of \(\mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})\). This procedure is called Poisson reduction. We shall demonstrate that the unreduced integrable system on \(\mathfrak {M}\) possesses a bi-Hamiltonian structure that descends to a bi-Hamiltonian structure of the spin Sutherland hierarchy via the Poisson reduction.

A holomorphic (or even a continuous) function on \(\mathfrak {M}\) that is invariant under the \(\mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})\) action (3.1) can be recovered from its restriction to \(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg}\), the subset of \(\mathfrak {M}\) consisting of the pairs (Q, L) with diagonal and regular \(Q\in \mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})\). Moreover, the restricted function inherits invariance with respect to the normalizer of the diagonal subgroup \(G_0< \mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})\), which includes \(G_0\). This explains the gauge symmetry of the hierarchy (1.1) and lends justification to the restriction on the eigenvalues of Q.

The bi-Hamiltonian structure on \(\mathfrak {M}\) involves in addition to the canonical Poisson bracket associated with the universal cotangent bundle symplectic form another one that we construct from Semenov–Tian–Shansky’s Poisson bracket of the Heisenberg double of \(\mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})\) endowed with its standard Poisson–Lie group structure [23]. Surprisingly, we could not find it in the literature that the canonical symplectic structure of the cotangent bundle \(\mathfrak {M}\) can be complemented to a bi-Hamiltonian structure in this manner. So this appears to be a novel result, which is given by Theorems 2.1, 2.2 and Proposition 2.4 in Sect. 2. The actual derivation of the second Poisson bracket (2.13) is relegated to an appendix. The heart of the paper is Sect. 3, where we derive the bi-Hamiltonian structure of the system (1.1) by Poisson reduction. The main results are encapsulated by Theorem 3.5 and Proposition 3.7. The first reduced Poisson bracket (3.34) is associated with the spin Sutherland interpretation by means of the parametrization (1.3). The formula of the second reduced Poisson bracket is given by equation (3.35). After deriving the holomorphic bi-Hamiltonian structure in Sect. 3, we shall explain in Sect. 4 that it allows us to recover the bi-Hamiltonian structures of the hyperbolic and trigonometric real forms derived earlier by different means [12, 13]. In the final section, we summarize the main results once more and highlight a few open problems.

2 Bi-Hamiltonian Hierarchy on the Cotangent Bundle

Let us denote \(G:= \mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})\) and equip its Lie algebra \({{\mathcal {G}}}:=\mathrm{gl}(n,\mathbb {C})\) with the trace form

This is a non-degenerate, symmetric bilinear form that enjoys the invariance property

Any \(X\in {{\mathcal {G}}}\) admits the unique decomposition

into strictly upper triangular part \(X_>\), diagonal part \(X_0\), and strictly lower triangular part \(X_<\). Thus, \({{\mathcal {G}}}\) is the vector space direct sum of the corresponding subalgebras

We shall use the standard solution of the modified classical Yang–Baxter equation on \({{\mathcal {G}}}\), \(r\in \mathrm {End}({{\mathcal {G}}})\) given by

and define also

Our aim is to present two holomorphic Poisson structures on the complex manifold

Denote \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})\) the commutative algebra of holomorphic functions on \(\mathfrak {M}\). For any \(F \in \mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})\), introduce the \({{\mathcal {G}}}\)-valued derivatives \(\nabla _1 F\), \(\nabla _1'F\) and \(d_2 F\) by the defining relations

and

where z is a complex variable and \(X\in {{\mathcal {G}}}\) is arbitrary. In addition, it will be convenient to define the \({{\mathcal {G}}}\)-valued functions \(\nabla _2 F\) and \(\nabla _2' F\) by

Note that

and a similar relation holds between \(\nabla _2 F\) and \(\nabla _2' F\) whenever L is invertible.

Theorem 2.1

For holomorphic functions \(F, H\in \mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})\), the following formulae define two Poisson brackets:

and

where the derivatives are evaluated at (g, L), and we put rX for r(X).

Proof

The first bracket is easily seen to be the Poisson bracket associated with the canonical symplectic form of the holomorphic cotangent bundle of G, which is identified with \(G \times {{\mathcal {G}}}\) using right-translations and the trace form on \({{\mathcal {G}}}\). The anti-symmetry and the Jacobi identity of the second bracket can be verified by direct calculation. More conceptually, they follow from the fact that locally, in a neighbourhood of \(({{\varvec{1}}}_n,{{\varvec{1}}}_n)\in G\times {{\mathcal {G}}}\), the second bracket can be transformed into Semenov–Tian–Shansky’s [23] Poisson bracket on the Heisenberg double of the standard Poisson–Lie group G. This is explained in the appendix. \(\square \)

Let us display the explicit formula of the Poisson brackets of the evaluation functions given by the matrix elements \(g_{ij}\) and the linear functions \(L_a := \langle T_a, L \rangle \) associated with an arbitrary basis \(T_a\) of \({{\mathcal {G}}}\), whose dual basis is \(T^a\), \(\langle T^b, T_a\rangle = \delta _a^b\). One may use the standard basis of elementary matrices, \(e_{ij}\) defined by \((e_{ij})_{kl} = \delta _{ik} \delta _{jl}\), but we find it convenient to keep a general basis. We obtain directly from the definitions

These give the first Poisson bracket immediately

Then, elementary calculations lead to the following formulae of the second Poisson bracket,

where \(\mathrm {sgn}\) is the usual sign function, and

By using the standard basis and evaluating the matrix multiplications, one may also spell out the last two equations as

where \(\delta _{(i>k)} := 1\) if \(i>k\) and is zero otherwise.

Let us recall that two Poisson brackets on the same manifold are called compatible if their arbitrary linear combination is also a Poisson bracket [18]. Compatible Poisson brackets often arise by taking the Lie derivative of a given Poisson bracket along a suitable vector field. If W is a vector field and \(\{\ ,\ \}\) is Poisson bracket, then the Lie derivative bracket is given by

where W[F] denotes the derivative of the function F along W. This bracket automatically satisfies all the standard properties of a Poisson bracket, except the Jacobi identity. However, if the Jacobi identity holds for \(\{\ ,\ \}^W\), then \(\{\ ,\ \}^W\) and \(\{\ ,\ \}\) are compatible Poisson brackets [10, 24].

Theorem 2.2

The first Poisson bracket of Theorem 2.1 is the Lie derivative of the second Poisson bracket along the holomorphic vector field, W, on \(\mathfrak {M}\) whose integral curve through the initial value (g, L) is

where \({{\varvec{1}}}_n\) is the unit matrix. Consequently, the two Poisson brackets are compatible.

Proof

By the general result quoted above [10, 24], it is enough to check that

holds for arbitrary holomorphic functions. Moreover, because of the properties of derivations, it is sufficient to verify this for the evaluation functions \(g_{ij}\) and \(L_a\) that yield coordinates on the manifold \(\mathfrak {M}\). Now, it is clear that \(W[g_{ij}]=0\) and \(W[L_a]\) is a constant. Therefore, if both F and H are evaluation functions, then \(\{ F,H\}_2^W= W[\{F,H\}_2]\). Thus, we see from (2.16) that the relation \(\{ g_{ij}, g_{kl}\}_2^W=0\) is valid. To proceed further, we use that \(W[g]\equiv \sum _{ij} W[g_{ij}] e_{ij}=0\) and \(W[L] \equiv \sum _a W[L_a] T^a= {{\varvec{1}}}_n\). Then, it follows from the formulae (2.17) and (2.18) that

Comparison with (2.15) implies the claim of the theorem. \(\square \)

Remark 2.3

The first line in (2.13) represents the standard multiplicative Poisson structure on the group G. The second line of \(\{\ ,\ \}_2\) can be recognized as the holomorphic extension of the well-known Semenov–Tian–Shansky bracket from G to \({{\mathcal {G}}}\), where G is regarded as an open submanifold of \({{\mathcal {G}}}\). We recall that the Semenov–Tian–Shansky bracket originates from the Poisson–Lie group dual to G [4, 23].

Denote by \(V_H^i\) \((i=1,2)\) the Hamiltonian vector field associated with the holomorphic function H through the respective Poisson bracket \(\{\ ,\ \}_i\). For any holomorphic function, we have the derivatives

We are interested in the Hamiltonians

Proposition 2.4

The vector fields associated with the functions \(H_m\) are bi-Hamiltonian, since we have

The derivatives of the matrix elements of \((g,L)\in \mathfrak {M}\) give

and the flow of \(V_{H_m}^2 = V_{H_{m+1}}^1\) through the initial value (g(0), L(0)) is

Proof

We obtain the derivatives

As a result of (2.10),

and thus, by (2.7),

The substitution of these relations into the formulae of Proposition 2.1 gives

By the very meaning of the Hamiltonian vector field associated with a function, these Poisson brackets imply (2.28), and then, (2.29) follows, too. \(\square \)

Like in the compact case [13], we call the \(H_m\) ‘free Hamiltonians’ and conclude from Proposition 2.4 that they generate a bi-Hamiltonian hierarchy on the holomorphic cotangent bundle \(\mathfrak {M}\).

3 The Reduced Bi-Hamiltonian Hierarchy

The essence of Hamiltonian symmetry reduction is that one keeps only the ‘observables’ that are invariant with respect to the pertinent group action. Here, we apply this principle to the adjoint action of G on \(\mathfrak {M}\), for which \(\eta \in G\) acts by the holomorphic diffeomorphism \(A_\eta \),

Thus, we keep only the G invariant holomorphic functions on \(\mathfrak {M}\), whose set is denoted

For invariant functions, the formula of the second Poisson brackets simplifies drastically.

Lemma 3.1

For \(F, H\in \mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})^G\), the formula (2.13) can be rewritten as follows:

Proof

We start by noting that for a G invariant function H, the relation

implies the identity

Indeed, since \(e^{zX} L e^{-zX} =L+ z X L - z LX + \mathrm {o}(z)\), taking the derivative of both sides of (3.4) at \(z=0\) gives

Since X is arbitrary, (3.5) follows.

Formally, (3.3) is obtained from (2.13) by setting r to zero, i.e. r cancels from all terms. The verification of this cancellation relies on the identity (3.5) and is completely straightforward. We express \(\nabla _1' H\) through the other derivatives with the help of (3.5), apply the same to \(\nabla _1' F\) and then collect terms in (2.13). To cancel all terms containing r, we use also that \(\langle rX,Y\rangle = - \langle X, rY\rangle \). After cancelling those terms, the equality (3.3) is obtained by utilizing the identity

which is verified by means of the definitions (2.1) and (2.10). \(\square \)

Lemma 3.2

\(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})^G\) is closed with respect to both Poisson brackets of Theorem 2.1.

Proof

Let us observe that the derivatives of the G invariant functions are equivariant,

and similar for \(\nabla _i' H\). In order to see this, notice that

holds for any \(X\in {{\mathcal {G}}}\) and \(\eta \in G\) if H is an invariant function. By taking derivative, we obtain

This leads to the \(i=1\) case of (3.8). The property

follows in a similar manner, and it implies the \(i=2\) case of (3.8).

By combining the formulas (2.12) and (3.3) with the equivariance property of the derivatives of F and H, we may conclude from (2.2) that if F, H are invariant, then so is \(\{F,H\}_i\) for \(i=1,2\). \(\square \)

We wish to characterize the Poisson algebras of the G invariant functions. To start, we consider the diagonal subgroup \(G_0 < G\),

and its regular part \(G_0^\mathrm {reg}\), where \(Q_i \ne Q_j\) for all \(i\ne j\). We let \({{\mathcal {N}}}< G\) denote the normalizer of \(G_0\) in G,

The normalizer contains \(G_0\) as a normal subgroup, and the corresponding quotient is the permutation group,

We also let \(G^\mathrm {reg}\subset G\) denote the dense open subset consisting of the conjugacy classes having representatives in \(G_0^\mathrm {reg}\). Next, we define

and

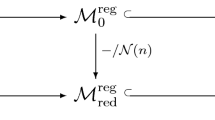

These are complex manifolds, equipped with their own holomorphic functions. Now, we introduce the chain of commutative algebras

The last two sets contain the respective invariant elements of \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})\), and \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})_\mathrm {red}\) contains the restrictions of the elements of \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})^G\) to \(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg}\). To put this in a more formal manner, let

be the tautological embedding. Then, pull-back by \(\iota \) provides an isomorphism between \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})^G\) and \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})_\mathrm {red}\). We here used that any holomorphic (or even continuous) function on \(\mathfrak {M}\) is uniquely determined by its restriction to \(\mathfrak {M}^\mathrm {reg}\). Similar, we obtain the map

which is also injective and surjective.

It may be worth elucidating why the pull-back (3.19) is an isomorphism. To this end, consider any map \(\eta : G^\mathrm {reg}\rightarrow G\) such that \(\eta (g) g \eta (g)^{-1} \in G_0^\mathrm {reg}\). Notice that \(\eta (g)\) is unique up to left-multiplication by elements of \({{\mathcal {N}}}\) (3.13). Consequently, if \(f\in \mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})^{{\mathcal {N}}}\), then

yields a well-defined, G invariant function on \(\mathfrak {M}^\mathrm {reg}\), which restricts to f. The function F is holomorphic, since locally, on an open set around any fixed \(g_0 \in G^\mathrm {reg}\), one can choose \(\eta (g)\) to depend holomorphically on g. Regarding this classical result of perturbation theory, see, for example, Theorem 2.1 in [1].

Definition 3.3

Let \(f,h \in \mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})_\mathrm {red}\) be related to \(F,H \in \mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})^G\) by \(f = F \circ \iota \) and \(h = H \circ \iota \). In consequence of Lemma 3.2, we can define \(\{f, h\}^\mathrm {red}_i \in \mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})_\mathrm {red}\) by the relation

This gives rise to the reduced Poisson algebras \((\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})_\mathrm {red}, \{\ ,\ \}_i^\mathrm {red})\).

The main goal of this paper is to derive formulae for the reduced Poisson brackets (3.21). To do so, we now note that any \(f\in \mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})\) has the \({{\mathcal {G}}}_0\)-valued derivative \(\nabla _1 f\) and the \({{\mathcal {G}}}\)-valued derivative \(d_2 f\), defined by

which are required for all \(X_0\in {{\mathcal {G}}}_0\) (2.4), \(X\in {{\mathcal {G}}}\). For any \(Q\in G_0\), the linear operator \({\mathrm {Ad}}_Q: {{\mathcal {G}}}\rightarrow {{\mathcal {G}}}\) acts as \({\mathrm {Ad}}_Q(X) = Q X Q^{-1}\). Set

where \({{\mathcal {G}}}_<\) (resp. \({{\mathcal {G}}}_>\)) is the strictly lower (resp. upper) triangular subalgebra of \({{\mathcal {G}}}\) introduced in (2.4). Notice that for \(Q\in G_0^\mathrm {reg}\) the operator \(({\mathrm {Ad}}_Q - {\mathrm {id}})\) maps \({{\mathcal {G}}}_\perp \) to \({{\mathcal {G}}}_\perp \) in an invertible manner. Building on (2.3), we have the decomposition

Using this, for any \(Q\in G_0^\mathrm {reg}\), the ‘dynamical r-matrix’ \({{\mathcal {R}}}(Q) \in \mathrm {End}({{\mathcal {G}}})\) is given by

and we remark its anti-symmetry property

This can be seen by writing \(Q=e^q\) with \(q\in {{\mathcal {G}}}_0\) , whereby we obtain

Here, \(\mathrm {ad}_q(X_\perp ) = [q, X_\perp ]\), which gives an anti-symmetric, invertible linear operator on \({{\mathcal {G}}}_\perp \). (The invertibility holds since \(Q\in G_0^\mathrm {reg}\) and is needed for \(\coth \frac{1}{2}\mathrm {ad}_q\) to be well defined on \({{\mathcal {G}}}_\perp \).) Below, we shall also employ the shorthand

Lemma 3.4

Consider \(f\in \mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})^{{\mathcal {N}}}\) given by \(f = F \circ \iota \), where \(F \in \mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M}^\mathrm {reg})^G\). Then, the derivatives of f and F satisfy the following relations at any \((Q,L) \in \mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg}\):

Proof

The equalities (3.29) hold since f is the restriction of F. In particular, it satisfies

Concerning (3.30), the equality of the \({{\mathcal {G}}}_0\) parts, \((\nabla _1 F(Q,L))_0 = (\nabla _1 f(Q,L))_0\), is obvious. Then, take any \(T \in {{\mathcal {G}}}_\perp \), for which we have

Therefore,

which implies (3.30). \(\square \)

Theorem 3.5

For \(f,h\in \mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})_\mathrm {reg}\), the reduced Poisson brackets defined by (3.21) can be described explicitly as follows:

and

where all derivatives are taken at \((Q,L)\in \mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg}\), and the notation (2.10) is in force. These formulae give two compatible Poisson brackets on \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})_\mathrm {red}\).

Proof

Let us begin with the first bracket, and note that at \((Q,L)\in \mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg}\), we have

since this follows from (3.30). Now, the third term together with the analogous one coming from \(- \langle \nabla _1 H, d_2 F\rangle \) cancels the last term of (2.12). Taking advantage of (3.26), the terms containing \({{\mathcal {R}}}(Q)\) give the expression written in (3.34).

Turning to the second bracket, we may start from (3.3), which is valid for elements of \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})^G\). Using (3.30) with \([L, d_2 f] = \nabla _2 f - \nabla _2' f\), we can write

This holds at (Q, L), since f, h are the restrictions of \(F,H\in \mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})^G\). We then combine (3.37) with the second term in (3.3). Collecting terms and using the anti-symmetry (3.26), we obtain

Moreover, we have

which cancels the contribution of the last two terms of (3.3). In conclusion, we see that the first and second lines in (3.37) and their counterparts ensuring anti-symmetry give the claimed formula (3.35).

We know from Theorem 2.2 that the original Poisson brackets on \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})\) are compatible, which means that their arbitrary linear combination \(\{\ ,\ \}:= x \{\ ,\ \}_1 + y\{\ ,\ \}_2\) satisfies the Jacobi identity. In particular, the Jacobi identity holds for elements of \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})^G\) as well. It is thus plain from Definition 3.3 that the arbitrary linear combination \(\{\ ,\ \}^\mathrm {red}= x \{\ ,\ \}_1^\mathrm {red}+ y \{\ ,\ \}_2^\mathrm {red}\) also satisfies the Jacobi identity. In this way, the compatibility of the two reduced Poisson brackets is inherited from the compatibility of the original Poisson brackets. \(\square \)

Remark 3.6

It can be shown that the formulae of Theorem 3.5 give Poisson brackets on \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})^{{\mathcal {N}}}\) and on \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})^{G_0}\) as well. Indeed, we can repeat the reduction starting from \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M}^\mathrm {reg})^G\) using the map (3.19), and this leads to the reduced Poisson brackets on \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})^{{\mathcal {N}}}\). Then, the closure on \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})^{G_0}\) follows from (3.14) and the local nature of the Poisson brackets. Because of (3.14), the quotient by \({{\mathcal {N}}}\) can be taken in two steps,

Since the action of \(S_n\) is free, the Poisson structure on \(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg}/{{\mathcal {N}}}\), which carries the functions \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})^{{\mathcal {N}}}\), lifts to a Poisson structure on \(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg}/G_0\), whose ring of functions is \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})^{G_0}\).

Now, we turn to the reduction of the Hamiltonian vector fields (2.28) to vector fields on \(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg}\). There are two ways to proceed. One may either directly associate vector fields to the reduced Hamiltonians using the reduced Poisson brackets or can suitably ‘project’ the original Hamiltonian vector fields. Of course, the two methods lead to the same result.

We apply the first method to the reduced Hamiltonians \(h_m:= H_m\circ \iota \in \mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})_\mathrm {red}\), which are given by

We have to find the vector fields \(Y_m^i\) on \(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg}\) that satisfy

These vector fields are not unique, since one may add any vector field to \(Y_m^i\) that is tangent to the orbits of the residual gauge transformations belonging to the group \(G_0\). This ambiguity does not affect the derivatives of the elements of \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})_\mathrm {red}\), and we may call any \(Y_m^i\) satisfying (3.42) the reduced Hamiltonian vector field associated with \(h_m\) and the respective Poisson bracket.

Now, a vector field Y on \(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg}\) is characterized by the corresponding derivatives of the evaluation functions that map \(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg}\ni (Q,L) \) to Q and L, respectively. We denote these derivatives by Y[Q] and Y[L]. Then, for any \(f\in \mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})\), the chain rule gives

Proposition 3.7

For all \(m\in \mathbb {N}\), the reduced Hamiltonian vector fields \(Y_m^i\) (3.42) can be specified by the formulae

Proof

It is enough to verify that any \(f \in \mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})_\mathrm {red}\) and \(h_m\) (3.41), for \(m\in \mathbb {N}\), satisfy

To obtain this, note that

Because of (3.29), these relations of the derivatives reflect those that appeared in the proof of Proposition 2.4. Putting them into (3.34) gives the claim for \(\{f, h_{m+1}\}^1_\mathrm {red}\), since

To get \(\{f, h_m\}_2^\mathrm {red}\), we also use that \(\nabla _2 f - \nabla _2' f = [L, d_2 f]\). Then, the identity

implies (3.45). \(\square \)

We conclude from Proposition 3.7 that the evolutional vector fields on \(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg}\) that underlie the equations (1.1) induce commuting bi-Hamiltonian derivations of the commutative algebra of functions \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})_\mathrm {red}\). In this sense, the holomorphic spin Sutherland hierarchy (1.1) possesses a bi-Hamiltonian structure. It is worth noting that the same statement holds if we replace \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})_\mathrm {red}\) by either of the two spaces of functions in the chain (3.17). According to (3.19), \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})^{{\mathcal {N}}}\) arises by considering the invariants \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M}^\mathrm {reg})^G\) instead of \(\mathrm {Hol}(\mathfrak {M})^G\). However, it is the latter space that should be regarded as the proper algebra of functions on the quotient \(\mathfrak {M}/G\) that inherits complete flows from the bi-Hamiltonian hierarchy on \(\mathfrak {M}\). According to general principles [20], the flows on the singular Poisson space \(\mathfrak {M}/G\) are just the projections of the unreduced flows displayed explicitly in (2.29).

4 Recovering the Real Forms

It is interesting to see how the bi-Hamiltonian structures of the real forms of the system (1.1), described in [12, 13], can be recovered from the complex holomorphic case. First, let us consider the hyperbolic real form which is obtained by taking Q to be a real, positive matrix, \(Q=e^q\) with a real diagonal matrix q, and L to be a Hermitian matrix. This means that we replace \(\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg}\) by the ‘real slice’

and consider the real functions belonging to \(C^\infty (\mathfrak {R}\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})^{\mathbb {T}^n}\), where \(\mathbb {T}^n\) is the unitary subgroup of \(G_0\). For such a functionFootnote 1, say f, we can take \(\nabla _1 f\) to be a real diagonal matrix and \(d_2 f\) to be a Hermitian matrix. In fact, in [12] we applied

and defined the derivatives by

where \(t\in \mathbb {R}\), \(\delta q\) is an arbitrary real-diagonal matrix and \(\delta L\) is an arbitrary Hermitian matrix. Notice that the definitions entail

and, with \(\nabla _2 f \equiv L d_2 f\),

Proposition 4.1

If we consider \(f, h \in C^\infty (\mathfrak {R}\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})^{\mathbb {T}^n}\) with (4.1) and insert their derivatives as defined above into the right-hand sides of the formulae of Theorem 3.5, then we obtain the following real Poisson brackets:

and

which reproduce the real bi-Hamiltonian structure given in Theorem 1 of [12].

Proof

The proof relies on the identity

This can be seen, for example, from the formula (3.27), since

because in the present case q is a real diagonal matrix. To deal with the first bracket, note that \(\langle \nabla _1 f, d_2 h\rangle = \langle \nabla _1 f, d_2 h\rangle _\mathbb {R}\) as both \(\nabla _1 f\) and \(d_2 h\) are Hermitian. By using (4.8) and the definition (3.28), we see that \([ d_2 f, d_2 h]_{{{\mathcal {R}}}(Q)}\) is Hermitian as well, and thus,

Consequently, we obtain the formula (4.6) from (3.34)

Turning to the second bracket, the equality \(\nabla _2' h = (\nabla _2 h)^\dagger \) (4.5) implies

simply because \(\langle X, Y \rangle ^* = \langle X^\dagger , Y^\dagger \rangle \) holds for all \(X,Y\in {{\mathcal {G}}}\). Thus, the first line of (3.35) correctly gives the first two terms of (2.194.7). Moreover, on account of (4.5) and (4.8), we obtain

Therefore, (3.35) gives (2.194.7).

Comparison with Theorem 1 in [12] shows that the formulae (4.6) and (2.194.7) reproduce the real bi-Hamiltonian structure derived in that paper. We remark that our \(d_2 f\) (4.3) was denoted \(\nabla _2 f\), and our variable q corresponds to 2q in [12]. Taking this into account, the Poisson brackets of Proposition 4.1, multiplied by an overall factor 2, give precisely the Poisson brackets of [12]. \(\square \)

The real form treated above yields the hyperbolic spin Sutherland model, and now, we deal with the trigonometric case. For this purpose, we introduce the alternative real slice

and consider the real functions belonging to \(C^\infty (\mathfrak {R}'\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})^{\mathbb {T}^n}\). A bi-Hamiltonian structure on this space of functions was derived in [13], where we used the pairing

and defined the derivatives \(D_1 f\), which is a real diagonal matrix, and \(D_2 f\), which is an anti-Hermitian matrix, by the requirement

where \(t\in \mathbb {R}\), \(\delta q\) is an arbitrary real-diagonal matrix and \(\delta L\) is an arbitrary Hermitian matrix. It is readily seen that

and comparison with (2.8) motivates the definitions

This implies that \(\nabla _2 f := L d_2 f\) and \(\nabla _2' f := (d_2 f) L\) satisfy (4.5) in this case as well. An important difference is that instead of (4.8) in the present case, we have

because in (3.27) q gets replaced by \(\mathrm{i}q\) with a real q, and then, instead of (4.9) we have \(\mathrm {ad}_{\mathrm{i}q} X^\dagger = (\mathrm {ad}_{\mathrm{i}q} X)^\dagger \).

Proposition 4.2

If we consider \(f, h \in C^\infty (\mathfrak {R}'\mathfrak {M}_0^\mathrm {reg})^{\mathbb {T}^n}\) with (4.13) and insert their derivatives as defined in (4.17) into the right-hand sides of the formulae of Theorem 3.5, then we obtain the following purely imaginary Poisson brackets:

and

Then, \(\mathrm{i}\{ f,h\}_1^{\mathbb {I}}\) and \(\mathrm{i}\{f,h\}_2^{\mathbb {I}}\) reproduce the real bi-Hamiltonian structure given in Theorem 4.5 of [13].

Proof

We detail only the first bracket, for which the first term of (3.34) gives

since \(\langle D_1 f, D_2 h\rangle \) is purely imaginary. The second term of (3.35) is similar, and the third term gives

since \([D_2 f, D_2 h]_{{{\mathcal {R}}}(Q)}\) is anti-Hermitian. To see this, we use (3.28) noting that \(D_2 f\) and, by (4.18), \({{\mathcal {R}}}(Q)(D_2f)\) are anti-Hermitian (and the same for h). Collecting terms, the formula (4.19) is obtained. The proof of (4.20) is analogous to the calculation presented in the proof of (2.194.7). The difference arises from the fact that now we have (4.18) instead of (4.8). The last statement of the proposition is a matter of obvious comparison with the formulae of Theorem 4.5 of [13] (but one should note that what we here call \(D_2 f\) was denoted \(d_2 f\) in that paper, and \(\langle \ ,\ \rangle _{\mathbb {I}}\) was denoted \(\langle \ ,\ \rangle \)). \(\square \)

5 Conclusion

In this paper, we developed a bi-Hamiltonian interpretation for the system of holomorphic evolution equations (1.1). The bi-Hamiltonian structure was found by interpreting this hierarchy as the Poisson reduction of a bi-Hamiltonian hierarchy on the holomorphic cotangent bundle \(T^*\mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})\), described by Theorems 2.1, 2.2 and Proposition 2.4. Our main result is given by Theorem 3.5 together with Proposition 3.7, which characterizes the reduced bi-Hamiltonian hierarchy. Then, we reproduced our previous results on real forms of the system [12, 13] by considering real slices of the holomorphic reduced phase space.

The first reduced Poisson structure and the associated interpretation as a spin Sutherland model are well known, and it is also known that the restrictions of the system to generic symplectic leaves of \(T^*\mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})/\mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})\) are integrable in the degenerate sense [21]. Experience with the real forms [13] indicates that the second Poisson structure should be tied in with a relation of the reduced system to spin Ruijsenaars–Schneider models, and degenerate integrability should also hold on the corresponding symplectic leaves. We plan to come back to this issue elsewhere. We remark in passing that although \(T^*\mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})/\mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})\) is not a manifold, this does not cause any serious difficulty, since it still can be decomposed as a disjoint union of symplectic leaves. This follows from general results on singular Hamiltonian reduction [20].

We finish by highlighting a few open problems for future work. First, it could be interesting to explore degenerate integrability directly on the Poisson space \(T^* \mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})/\mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})\), suitably adapting the formalism of the paper [15]. Second, we wish to gain a better conceptual understanding of the process whereby one goes from holomorphic Poisson spaces and integrable systems to their real forms and apply it to our case. The results of the recent study [3] should be relevant in this respect. Finally, it is a challenge to generalize our construction from the hyperbolic/trigonometric case to elliptic systems. The existence of a bi-Hamiltonian structure for the elliptic spin Calogero–Moser system appears to follow from the existence of such a structure for an integrable elliptic top on \(\mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})\) [14] via the symplectic Hecke correspondence [16, 19].

Notes

We could also consider real-analytic functions.

References

Andrew, A.L., Chu, K.-W.E., Lancaster, P.: Derivatives of eigenvalues and eigenvectors of matrix functions. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 14, 903–926 (1993)

Aniceto, I., Avan, J., Jevicki, A.: Poisson structures of Calogero–Moser and Ruijsenaars–Schneider models. J. Phys. A 43, 185201 (2010). arXiv:0912.3468 [hep-th]

Arathoon, P., Fontaine, M.: Real forms of holomorphic Hamiltonian systems. arXiv:2009.10417 [math.SG]

Arutyunov, G.: Elements of Classical and Quantum Integrable Systems. Springer, Berlin (2019)

Babelon, O., Bernard, D., Talon, M.: Introduction to Classical Integrable Systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2003)

Balog, J., Da̧browski, L., Fehér, L.: Classical \(r\)-matrix and exchange algebra in WZNW and Toda theories. Phys. Lett. B 244, 227–234 (1990)

Bartocci, C., Falqui, G., Mencattini, I., Ortenzi, G., Pedroni, M.: On the geometric origin of the bi-Hamiltonian structure of the Calogero–Moser system. Int. Math. Res. Not. 2010, 279–296 (2010). arXiv:0902.0953 [math-ph]

De Sole, A., Kac, V.G., Valeri, D.: Classical affine W-algebras and the associated integrable Hamiltonian hierarchies for classical Lie algebras. Commun. Math. Phys. 360, 851–918 (2018). arXiv:1705.10103 [math-ph]

Etingof, P., Varchenko, A.: Geometry and classification of solutions of the classical dynamical Yang–Baxter equation. Commun. Math. Phys. 192, 77–120 (1998). arXiv:q-alg/9703040

Falqui, G., Magri, F., Pedroni, M.: Bihamiltonian geometry, Darboux coverings, and linearization of the KP hierarchy. Commun. Math. Phys. 197, 303–324 (1998). arXiv:solv-int/9806002

Falqui, G., Mencattini, I.: Bi-Hamiltonian geometry and canonical spectral coordinates for the rational Calogero–Moser system. J. Geom. Phys. 118, 126–137 (2017). arXiv:1511.06339 [math-ph]

Fehér, L.: Bi-Hamiltonian structure of a dynamical system introduced by Braden and Hone. Nonlinearity 32, 4377–4394 (2019). arXiv:1901.03558 [math-ph]

Fehér, L.: Reduction of a bi-Hamiltonian hierarchy on \(T^*U(n)\) to spin Ruijsenaars–Sutherland models. Lett. Math. Phys. 110, 1057–1079 (2020). arXiv:1908.02467 [math-ph]

Khesin, B., Levin, A., Olshanetsky, M.: Bihamiltonian structures and quadratic algebras in hydrodynamics and on non-commutative torus. Commun. Math. Phys. 250, 581–612 (2004). arXiv:nlin/0309017 [nlin.SI]

Laurent-Gengoux, C., Miranda, E., Vanhaecke, P.: Action-angle coordinates for integrable systems on Poisson manifolds. Int. Math. Res. Not. 2011, 1839–1869. arXiv:0805.1679 [math.SG]

Levin, A.M., Olshanetsky, M.A., Zotov, A.: Hitchin systems—symplectic Hecke correspondence and two-dimensional version. Commun. Math. Phys. 236, 93–133 (2003). arXiv:nlin/0110045 [nlin.SI]

Li, L.-C., Xu, P.: A class of integrable spin Calogero–Moser systems. Commun. Math. Phys. 231, 257–286 (2002). arXiv:math/0105162 [math.QA]

Magri, F.: A simple model of the integrable Hamiltonian equation. J. Math. Phys. 19, 1156–1162 (1978)

Olshanetsky, M.: Classical integrable systems and gauge field theories. Phys. Part. Nucl. 40, 93–114 (2009). arXiv:0802.3857 [hep-th]

Ortega, J.-P., Ratiu, T.: Momentum Maps and Hamiltonian Reduction. Birkäuser, Basel (2004)

Reshetikhin, N.: Degenerate integrability of spin Calogero–Moser systems and the duality with the spin Ruijsenaars systems. Lett. Math. Phys. 63, 55–71 (2003). arXiv:math/0202245 [math.QA]

Ruijsenaars, S.N.M.: Systems of Calogero–Moser type. In: Proceedings of the 1994 CRM-Banff Summer School: Particles and Fields, pp. 251–352. Springer (1999)

Semenov–Tian–Shansky, M.A.: Dressing transformations and Poisson group actions. Publ. RIMS 21, 1237–1260 (1985)

Smirnov, R.G.: Bi-Hamiltonian formalism: a constructive approach. Lett. Math. Phys. 41, 333–347 (1997)

Suris, Y.B.: The Problem of Integrable Discretization: Hamiltonian Approach. Birkhäuser, Basel (2003)

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Maxime Fairon for several useful remarks on the manuscript. I am also grateful to Mikhail Olshanetsky for drawing my attention to relevant references. This work was supported by the NKFIH research Grant K134946 and was also supported partially by the Project GINOP-2.3.2-15-2016-00036 co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund and the budget of Hungary.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Szeged, Open Access Fund 5393.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Nikolai Kitanine.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A The Origin of the Second Poisson Bracket on \(G\times {{\mathcal {G}}}\)

A The Origin of the Second Poisson Bracket on \(G\times {{\mathcal {G}}}\)

In this appendix, we outline how the Poisson bracket \(\{\ ,\ \}_2\) (2.13) arises from the standard Poisson bracket [23] on the Heisenberg double of the \(\mathrm{GL}(n,\mathbb {C})\) Poisson–Lie group.

We start with the complex Lie group \(G\times G\) and denote its elements as pairs \((g_1, g_2)\). We equip the corresponding Lie algebra \({{\mathcal {G}}}\oplus {{\mathcal {G}}}\) with the non-degenerate bilinear form \(\langle \ , \ \rangle _2\), given by

for all \((X_1,X_2)\) and \((Y_1,Y_2)\) from \({{\mathcal {G}}}\oplus {{\mathcal {G}}}\). Then, we have the isotropic subalgebras,

and

Recall that \(r_\pm \) are defined in (2.6), and note that \({{\mathcal {G}}}\oplus {{\mathcal {G}}}\) is the vector space direct sum of the disjunct subspaces \({{\mathcal {G}}}^\delta \) and \({{\mathcal {G}}}^*\); \({{\mathcal {G}}}^\delta \) is isomorphic to \({{\mathcal {G}}}\), and \({{\mathcal {G}}}^*\) can be regarded as its linear dual space. We also introduce the corresponding subgroups of \(G\times G\),

and

where \(G_>\), \(G_<\) and \(G_0\) are the connected subgroups of G associated with the Lie subalgebras in the decomposition (2.4). That is, \(G_0\) contains the diagonal, invertible complex matrices, and \(G_>\) (resp. \(G_<\)) consists of the upper triangular (resp. lower triangular) complex matrices whose diagonal entries are all equal to 1.

In order to describe the pertinent Poisson structures, we need the Lie algebra-valued derivatives of holomorphic functions. For \({{\mathcal {F}}}\in \mathrm {Hol}(G\times G)\), we denote its \({{\mathcal {G}}}\oplus {{\mathcal {G}}}\)-valued left- and right-derivatives, respectively, by \({{\mathcal {D}}}{{\mathcal {F}}}\) and \({{\mathcal {D}}}' {{\mathcal {F}}}\). For example, we have

where \(z\in \mathbb {C}\) and \((X_1,X_2)\) runs over \({{\mathcal {G}}}\oplus {{\mathcal {G}}}\). Defined using \(\langle \ ,\ \rangle _2\), a holomorphic function \(\phi \) on \(G^\delta \) has the \({{\mathcal {G}}}^*\)-valued left- and right-derivatives, \(D \phi \) and \(D'\phi \). Analogously, the left- and right-derivatives \(D\chi \) and \(D'\chi \) of \(\chi \in \mathrm {Hol}(G^*)\) are \({{\mathcal {G}}}^\delta \)-valued.

Now, we recall [23] that \(G\times G\) carries two natural Poisson brackets, which are given by

where \(R:= \frac{1}{2} \left( P_{{{\mathcal {G}}}^\delta } - P_{{{\mathcal {G}}}^*}\right) \) with the projections \(P_{{{\mathcal {G}}}^\delta }\) onto \({{\mathcal {G}}}^\delta \) and \(P_{{{\mathcal {G}}}^*}\) onto \({{\mathcal {G}}}^*\) defined via the vector space direct sum \({{\mathcal {G}}}\oplus {{\mathcal {G}}}= {{\mathcal {G}}}^\delta + {{\mathcal {G}}}^*\). The minus bracket is called the Drinfeld double bracket, and the plus one the Heisenberg double bracket. The former makes \(G\times G\) into a Poisson–Lie group, having the Poisson submanifolds \(G^\delta \) and \(G^*\), and the latter is symplectic in a neighbourhood of the identity.

Let us consider an open neighbourhood of the identity in \(G\times G\) whose elements can be factorized as

with \(g_{\delta L}, g_{\delta R}\in G^\delta \) and \(g_{*L}, g_{*R}\in G^*\). Restricting \((g_1, g_2)\) as well as all constituents in the factorizations to be near enough to the respective identity elements, the map

yields a local, biholomorphic diffeomorphism. As the first step towards deriving the bracket in (2.13), we use this diffeomorphism to transfer the plus Poisson bracket to a neighbourhood of the identity of \(G^\delta \times G^*\). The resulting Poisson structure then extends holomorphically to the full of \(G^\delta \times G^*\). For \({{\mathcal {G}}}, {{\mathcal {H}}}\in \mathrm {Hol}(G^\delta \times G^*)\), we denote the resulting Poisson bracket by \(\{{{\mathcal {F}}},{{\mathcal {H}}}\}_+'\). One can verify that it takes the following form:

where the derivatives on the right-hand side are taken at \((g_\delta ,g_*)\in G^\delta \times G^*\). The subscripts 1 and 2 refer to derivatives with respect to the first and second arguments; they are \({{\mathcal {G}}}^*\)- and \({{\mathcal {G}}}^\delta \)-valued, respectively. For example, we have

and

It is worth noting that

The derivatives \(D_1'\) and \(D_2'\) are defined analogously, cf. (2.8). The derivation of the formula (A.10) from \(\{\ ,\ \}_+\) in (A.7) can follow closely the proof of Proposition 2.1 in [13], where another Heisenberg double was treated. The formula (A.10) itself has the same structure as formula (2.18) in [13], and thus, we here omit its derivation.

In the second step towards getting \(\{\ ,\ \}_2\) in (2.13), we make use of a biholomorphic diffeomorphism between open neighbourhoods of the identity element of \(G^\delta \times G^*\) and the element \(({{\varvec{1}}}_n, {{\varvec{1}}}_n) \in G\times {{\mathcal {G}}}\). For \(g_\delta = (g,g)\) and \(g_* = (g_> g_0, (g_0 g_<)^{-1} )\), this is given by the map

A (locally defined) function \({{\mathcal {F}}}\) on \(G^\delta \times G^*\) then corresponds to a (locally defined) function F on \(G\times {{\mathcal {G}}}\) according to

To proceed further, we need an auxiliary result.

Lemma 5.1

For the functions \({{\mathcal {F}}}\) and F in (A.15), the derivatives \(D_i {{\mathcal {F}}}\) and \(D_i' {{\mathcal {F}}}\) \((i=1,2)\) defined in (A.11), (A.12) and the derivatives \(\nabla _i F\), \(\nabla _i' F\) defined in (2.8)–(2.10) are related as follows:

and

Proof

We begin by pointing out the identity

which is a consequence of (A.1) and (A.13). Now, the definitions of the derivatives ensure that

Because of (A.20) and the non-degeneracy of both pairings, this implies the identity (A.16), and (A.17) results in the same manner.

To derive (A.18), we may forget the \(g_\delta \)-dependence and assume (just for simplicity of writing) that \({{\mathcal {F}}}\) depends only on \(g_*\), which we now write as

referring to (A.5). By setting \({\hat{X}}:= (r_+X, r_-X)\) and writing D for \(D_2\), we have

since \(L= g_+ g_-^{-1}\). By simply expanding the exponential functions, this is equal to

To get this, we used the definitions (2.1), (2.10) together with the anti-symmetry of r (2.5) with respect to the trace form, and the identity (A.20). Thus, we have shown that

for arbitrary \({\hat{X}} \in {{\mathcal {G}}}^*\) (A.3). This implies (A.18) since \({{\mathcal {G}}}^\delta \) (A.2) and \({{\mathcal {G}}}^*\) (A.3) are in duality with respect to the non-degenerate pairing \(\langle \ ,\ \rangle _2\).

In order to derive (A.19), we again assume that \({{\mathcal {F}}}\) depends only on \(g_* = (g_+, g_-)\). Then, we note that, for any \(V\in {{\mathcal {G}}}\),

Of course, now \(D' {{\mathcal {F}}}(g_*) \equiv D'_2 {{\mathcal {F}}}(g_*) \in {{\mathcal {G}}}^\delta \). If we consider the decomposition

then

By using these, we can write

Hence, we have shown that

which implies the claimed formula. \(\square \)

We apply the local diffeomorphism (A.14) to transfer the Poisson bracket \(\{\ ,\ \}_+'\) (A.10) to a Poisson bracket of holomorphic functions defined locally on \(G \times {{\mathcal {G}}}\) (that is, on an open subset containing \(({{\varvec{1}}}_n, {{\varvec{1}}}_n) \in G\times {{\mathcal {G}}}\)). The formula of the transferred Poisson bracket is obtained by substituting the identities of Lemma 5.1 into (A.10) and then simply collecting terms. The result turns out to have the form \(\{\ ,\ \}_2\) given in (2.13), and it naturally extends to a globally well-defined Poisson bracket of holomorphic functions on \(\mathfrak {M}= G \times {{\mathcal {G}}}\).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fehér, L. Bi-Hamiltonian Structure of Spin Sutherland Models: The Holomorphic Case. Ann. Henri Poincaré 22, 4063–4085 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00023-021-01084-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00023-021-01084-7