Abstract

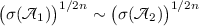

The spectra of n-Laplacian operators \((-\Delta )^n\) on finite metric graphs are studied. An effective secular equation is derived and the spectral asymptotics are analysed, exploiting the fact that the secular function is close to a trigonometric polynomial. The notion of the quasispectrum is introduced, and its uniqueness is proved using the theory of almost periodic functions. To achieve this, new results concerning roots of functions close to almost periodic functions are proved. The results obtained on almost periodic functions are of general interest outside the theory of differential operators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 Motivation

Quantum graphs have proved to be an important area of research in both physics and mathematics. By quantum graphs, one understands ordinary differential equations on metric graphs, coupled by matching conditions at the vertices. Most works on the subject consider second-order (Schrödinger) differential operators (see, for example, [8, 20, 21, 25, 28, 34, 36, 40, 41, 45, 51]), but the methods developed can be generalised to differential expressions of arbitrary order. This has already been done in the case of first-order (Dirac and momentum) and to some extent fourth-order operators (e.g. [11, 13, 22, 27, 32]). The recent status of research in this area is well reflected in the monographs [8, 41].

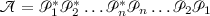

Recent development in spectral theory of Schrödinger operators on metric graphs has seen a connection with trigonometric polynomials and the classical theory of almost periodic functions (see [12, 47]). These studies were based on the Gutkin–Kottos–Smilansky formula for the secular equation for the Laplacian [28, 35]

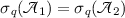

where \( {\mathbf {S}}_\text {e} \) and \( {\mathbf {S}}_\text {v} \) are the edge and vertex scattering matrices (see Sect. 5), respectively. For scaling-invariant vertex conditions, \( {\mathbf {S}}_\text {v} \) is independent of the energy, whilst the entries of \( {\mathbf {S}}_\text {e} \) are given by exponentials with real frequencies; hence, the secular function is a trigonometric polynomial of the form

where \( a_j \in {\mathbb {C}} \) and \( r_j \in {\mathbb {R}}\), not necessarily rationally dependent. For general vertex conditions and Schrödinger operators with nonzero potentials, the eigenvalues are not given by zeros of trigonometric polynomials, but are asymptotically close to such zeros, leading to the notion of asymptotic isospectrality. The approximating trigonometric polynomials correspond to Laplacians with uniquely determined scaling-invariant vertex conditions. Due to the rigidity of zeros of trigonometric polynomials, one may not only describe spectral asymptotics, but also solve certain inverse problems.

The present paper is devoted to the spectral theory of higher-order differential operators on metric graphs, more precisely of n-Laplacians associated with the differential expression \( \left( - \frac{\mathrm{d}^2}{\mathrm{d}x^2} \right) ^n \) on the edges. Our goal is twofold:

-

to derive an efficient parameterisation of all self-adjoint vertex conditions leading to an explicit secular equation generalising (1.1);

-

to study spectral asymptotics for n-Laplacians with scaling-invariant conditions,

postponing the analysis of general vertex conditions to the second part of our study.

It appears that even the spectra of n-Laplacians with scaling-invariant vertex conditions are hardly ever described by trigonometric polynomials or, even more generally, almost periodic functions. Nevertheless, we show that such functions do play an important role in their spectral analysis. In particular we introduce the notion of the quasispectrum, which not only asymptotically approximates the actual spectrum but is also unique. The quasispectrum coincides with the (2nth root of the) spectrum of a certain Dirac operator on the same metric graph which itself is therefore described by zeros of a trigonometric polynomial. This is akin to determining the Laplacian spectrum from the eigenvalues of the Schrödinger operator in earlier works. This once again illustrates the power of almost periodic functions and the rigidity of their zeros.

A key ingredient in all of this is the study of roots of a certain class of functions which are close to almost periodic functions, holomorphic perturbations as we call them: we show that the roots of a holomorphic perturbation of an almost periodic function are aymptotically close to those of the almost periodic function. One can prove a kind of equivalence relation between such functions, which has the consequence that two n-Laplacians are asymptotically isospectral if and only if they have the same quasispectrum. For this purpose, new results concerning (classical) almost periodic functions are proved; we believe that these results have wider applications.

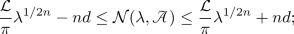

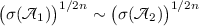

To understand why it is unavoidable to use almost periodic functions, as opposed to more conventional approaches, we recall the asympotics for the Schrödinger operator. The eigenvalues (discrete and accumulating towards \( + \infty \)) satisfy Weyl’s law [8, 41]

with \( {\mathcal {L}} \) being the total length of the graph. However, no further refinement of the asymptotics of the form \(k_j = \frac{\pi }{{\mathcal {L}}} j + c_0 + c_{-1} j^{-1} + \cdots \) is possible unless the graph is an interval or a loop. One may derive certain asymptotic expansions of this type, but just for subsequences of eigenvalues like in [16].

In the first half of this paper, we revise the issue of vertex conditions. There is already a well-established theory for parameterising self-adjoint extensions of symmetric operators by unitary matrices using boundary triples (see [14, 18, 19, 26, 33]). Equivalent, more classical approaches include von Neumann extension theory (see [56]) or Birman–Krein–Vishik theory (see [1]). For Schrödinger operators on metric graphs, parameterisation of vertex conditions via the scattering matrix has proved to be useful, not least due to clear physical interpretation of the parameter. Our first goal was thus to establish a similar approach for n-Laplacians. Using unitary parameterisation via boundary triples, one can easily describe which conditions are scaling-invariant, or non-Robin, but the corresponding secular equation is difficult to analyse. Therefore, we develop an alternative approach via the so-called vertex transmission matrix which leads to a more effective secular equation, allowing one to study spectral asymptotics. Note that in the case of the Laplacian (\(n=1\)), the two approaches are identical, and the parameter coincides with the vertex scattering matrix. Surprisingly the secular equation for higher-order operators has not been written in any form yet.

In the second half of the paper, the focus turns to almost periodic functions, and from this, we establish spectral asymptotics for n-Laplacians with scaling-invariant vertex conditions by comparing the secular equation with a certain reference trigonometric polynomial, the set of whose positive roots we identify as the quasispectum. As we have already mentioned, the quasispectrum is unique and can be interpreted as the spectrum of a Dirac operator. This operator replaces the reference Laplacian (denoted \( L_0^{{\mathbf {S}}_{\mathrm{v}} (\infty )}\) in [47]) used to describe the asymptotics for the Schrödinger equation.

Throughout this paper, we are focused on the 2nth derivative \((-\Delta )^n\), but the results obtained open the way to studying spectral asymptotics for arbitrary ordinary differential operators on graphs with the most general vertex conditions and variable coefficients.

1.2 Vertex Conditions and Spectral Asymptotics

From a mathematical point of view, quantum graphs is a perfect area for experiment relating to extension theory of symmetric operators. The most general vertex conditions for self-adjoint extensions of symmetric operators can be described using the theory of boundary triples [6], also [26, 33]. For Laplacians on metric graphs, all possible vertex conditions were first described in [34]; this approach resembles our formula (2.5) and has the disadvantage of being non-unique—multiplying all matrices \( A_r \) by an invertible matrix does not change the linear solution subspace. Two alternative but complementing approaches leading to unique set of parameters were suggested in [36] (in terms of a linear subspace and a Hermitian matrix) and [45] (in terms of the vertex scattering matrix). The first approach is efficient when working with the quadratic form and therefore is efficient in proving spectral estimates, whilst the vertex scattering matrix used in the second approach directly appears in the secular equation. Methods for estimating eigenvalues, such as graph surgery, are discussed in [7, 23, 30, 31, 42, 43, 52], and properties of the ground state in the presence of a potential in [39, 46]. Spectral asymptotics are discussed in [16, 37, 47, 48]. The notion of isospectrality for these operators was first discussed in [28] and then in [4, 5, 53], and asymptotic isospectrality in [47]. Inverse problems are addressed in [2, 3, 38, 43, 48, 54, 55].

In the case of bi-Laplacians, a characterisation of all vertex conditions corresponding to self-adjoint operators can be found in [27]. More detailed expositions involving spectra (e.g. Weyl asymptotics) for bi-Laplacians with selected vertex conditions can be found for instance in [17]. See also [49] for physical and [32] for mathematical interpretations of certain conditions. Vertex conditions for differential operators of arbitrary order have been derived in [15]; the parameterisation again resembles our formula (2.5).

2 Differential Operators on Metric Graphs

Matrices of various sizes in terms of the natural numbers d and n, recurring throughout this paper, will play a range of roles. The most important matrices have sizes \(d\times d\), which for consistency we denote in bold, e.g. \({\mathbf {A}}\), and \(nd\times nd\), which are double-struck, e.g. \({\mathbb {A}}\). Those of other sizes have no special notation, e.g. A, and in that case the dimensions are always specified.

2.1 Differential Operators: Metric Graphs and Vertex Conditions

Let E be a finite set of edges, that is, intervals taken from different copies of \({\mathbb {R}}\). Let \(N:=|E|\) be the total number of edges, and d the total number of endpoints. For the majority of this paper, we consider only compact graphs, so the intervals are all bounded, in which case \(d=2N\). Labelling the edges in E as \(e_1,\dots e_N\), we shall label the endpoints \(x_1,\dots ,x_d\) to satisfy \(e_j=[x_j,x_{N+j}]\) for \(j=1,\dots ,N\).Footnote 1 Under this labelling, if \(j\le N\) then we call \(x_j\) (the smallest value in the interval) a left endpoint, whilst for \(N<j\le d\), we call \(x_j\) (the largest value in the interval) a right endpoint. Where necessary, we denote by \(e(x_j)\) the edge that has \(x_j\) as an endpoint.

Consider the set of all endpoints \( \left\{ x_j \right\} _{j=1}^d \) and its partition into M equivalence classes v forming the vertex set V:

The set of vertices induces an equivalence relation \(\sim \) on the disjoint union of edges as follows: given \(x,y\in \bigsqcup _{e\in E}e\), we say that \(x\sim y\) if and only if either

-

(i)

x and y belong to the same edge \(e\in E\) and \(x=y\), or

-

(ii)

x and y are endpoints that belong to the same vertex v.

This equivalence relation yields a metric graph

Given a metric graph \(\Gamma \), we are interested in operators in the Hilbert space \(L_2(\Gamma ):=\bigoplus _{e\in E} L_2(e)\). The inner product associated with this space is the sum of standard \(L_2\) inner products on each edge \(e\in E\). Explicitly, that is

We usually omit the subscript when writing the \(L_2(\Gamma )\) inner product.

The focus of this paper is on differential operators in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) with formal expression \({\mathfrak {p}}^{2n}\) for some \(n\in {\mathbb {N}}\), where \({\mathfrak {p}}:=-\mathrm {i}\frac{\mathrm {d}}{\mathrm {d}x}\). However, for later convenience, the following conventions are stated more generally permitting \(n\in \frac{1}{2}{\mathbb {N}}\). The functions in the domain of such an operator are all from the Sobolev space \({{\widetilde{H}}}^{2n}(\Gamma )\), which is the set of functions in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) which on each edge e are contained in the Sobolev space \(H^{2n}(e)=W_2^{2n}(e)\). In general, we shall impose further restrictions on the domain in the form of linear conditions at the endpoints. To be able to write such conditions independently of the direction of parameterisation of the edges, we define for each \(r=0,1,...,2n-1\) the normal r th derivative of \(\psi \in {{\widetilde{H}}}^{2n}(\Gamma )\) at the endpoint \(x_j\) to be

where

We then denote by \(\partial ^r\varvec{\Psi }\) the vector of normal rth derivatives at all endpoints of E (ordered according to the indices of the endpoints). We usually write \(\varvec{\Psi }:=\partial ^0\varvec{\Psi }\).

Given \(n\in \frac{1}{2}{\mathbb {N}}\), the most general (linear) boundary conditions that can be imposed on functions in \({{\widetilde{H}}}^{2n}(\Gamma )\) are of the form

where \( A_0, A_1,\dots , A_{2n-1}\) are arbitrary \(l\times d\) matrices for a certain \(l\in {\mathbb {N}}\). Without loss of generality, it may be assumed that \(l\le 2nd\) since otherwise there will certainly be redundancies. Taking \(l=2nd\) is thus sufficient to express all possible conditions using matrices of consistent dimensions.

The domain of an operator  in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) given by

in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) given by  with boundary conditions (2.5) is

with boundary conditions (2.5) is

The conditions governed by (2.5) are called the vertex conditions for  . Note that the matrices \( A_r \) are not uniquely determined by the solution space for (2.5). For integer n, it will be established in Sect. 3.1 that any vertex conditions leading to self-adjoint operators can be written in this form with \(l=nd\).

. Note that the matrices \( A_r \) are not uniquely determined by the solution space for (2.5). For integer n, it will be established in Sect. 3.1 that any vertex conditions leading to self-adjoint operators can be written in this form with \(l=nd\).

The Hilbert spaces \(L_2(\Gamma )\) and \({{\widetilde{H}}}^{2n}(\Gamma )\) are independent of the vertex structure, i.e. how the edges are connected to one another. In other words, one could substitute \(\Gamma \) with any other metric graph with the same edges, and the Hilbert spaces would be the same. However, it is natural to assume that the vertex conditions (2.5) of an operator in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) respect the vertex structure of \(\Gamma \). This means that the conditions can be written separately connecting boundary values associated with each vertex v. In other words, considering equivalent conditions and simultaneously permuting the endpoints from \( {\mathbb {C}}^d \), all matrices \( A_r \) can be put into the same block diagonal form determined by the vertices. Moreover, such representation should be minimal in the sense that it is impossible to write equivalent vertex conditions with a finer partition of the endpoints into equivalence classes.

Everything that has been said so far can clearly be adapted for more general linear differential expressions \({\mathfrak {a}}\), but one would have to be more careful when stating the admissible domains.

2.2 First-Order Operators

The first-order differential operators in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) with expression \({\mathfrak {p}}\) are the only odd-ordered operators that will play a significant role in our studies (see for instance [22]). Fixing \(l\ge d\), vertex conditions of any such operator with differential expression \({\mathfrak {p}}\) can be expressed in the form \(A_0\varvec{\Psi }=0\) for some \(l\times d\) matrix \(A_0\).Footnote 2 Given such a matrix \( A_0\), denote by \([ A_0]\) its equivalence class modulo left multiplication by invertible \(l\times l\) matrices. The vertex conditions corresponding to any element of this class are equivalent. Denote by  the operator

the operator  with these vertex conditions. Defining the sign matrix

with these vertex conditions. Defining the sign matrix

and \(\sigma (x_j)\) is given by (2.4), the following simple result holds.

Lemma 2.1

The adjoint of the operator  is given by

is given by

where \(B_0\) is any \(l\times d\) matrix with \(rank (B_0)=d-rank ( A_0 )\) and such that \( A_0B_0^*=0\).

Proof

The domain of  is the set of \(\phi \in L_2(\Gamma )\) for which

is the set of \(\phi \in L_2(\Gamma )\) for which  is bounded among \(\psi \in \text {dom}(A)\) with respect to the \(L_2\)-norm. Taking \( \psi \in C_0^\infty (e)\), we see that

is bounded among \(\psi \in \text {dom}(A)\) with respect to the \(L_2\)-norm. Taking \( \psi \in C_0^\infty (e)\), we see that  is contained in \( \bigoplus _e W_2^1 (e).\) For \(\phi \in \bigoplus _e W_2^1 (e)\), the inner product equates to \(\langle {\mathfrak {p}}\phi ,\psi \rangle -\mathrm {i}\langle \varvec{\Sigma }\varvec{\Phi },\varvec{\Psi }\rangle _{{\mathbb {C}}^d}\). As \(\ker A_0=\text {ran}\,B_0^*\) for any matrix \(B_0\) like in the statement of the lemma, this form is bounded if and only if \(\langle \varvec{\Sigma }\varvec{\Phi },\varvec{\Psi }\rangle _{{\mathbb {C}}^d}=0\) for all \(\varvec{\Psi }\in \text {ran}\,B_0^*\), that is if and only if \(\varvec{\Sigma }\varvec{\Phi }\in \ker B_0\). \(\square \)

is contained in \( \bigoplus _e W_2^1 (e).\) For \(\phi \in \bigoplus _e W_2^1 (e)\), the inner product equates to \(\langle {\mathfrak {p}}\phi ,\psi \rangle -\mathrm {i}\langle \varvec{\Sigma }\varvec{\Phi },\varvec{\Psi }\rangle _{{\mathbb {C}}^d}\). As \(\ker A_0=\text {ran}\,B_0^*\) for any matrix \(B_0\) like in the statement of the lemma, this form is bounded if and only if \(\langle \varvec{\Sigma }\varvec{\Phi },\varvec{\Psi }\rangle _{{\mathbb {C}}^d}=0\) for all \(\varvec{\Psi }\in \text {ran}\,B_0^*\), that is if and only if \(\varvec{\Sigma }\varvec{\Phi }\in \ker B_0\). \(\square \)

For instance, the minimal operator  is related to the maximal operator

is related to the maximal operator  via

via  . The product

. The product  is a Laplacian with Dirichlet vertex conditions at all endpoints, whilst

is a Laplacian with Dirichlet vertex conditions at all endpoints, whilst  has Neumann vertex conditions at all endpoints. The metric graphs whose vertex structure is respected by the vertex conditions of these operators have all their edges disconnected. On the other hand, given a metric graph \(\Gamma \), if

has Neumann vertex conditions at all endpoints. The metric graphs whose vertex structure is respected by the vertex conditions of these operators have all their edges disconnected. On the other hand, given a metric graph \(\Gamma \), if  is the operator which imposes continuity of functions in its domain at the vertices of \(\Gamma \), then

is the operator which imposes continuity of functions in its domain at the vertices of \(\Gamma \), then  is the operator which imposes the condition that \(\sum _{x_j\in v}\sigma (x_j)\psi (x_j)=0\) at each vertex v. Then the domain of the Laplacian

is the operator which imposes the condition that \(\sum _{x_j\in v}\sigma (x_j)\psi (x_j)=0\) at each vertex v. Then the domain of the Laplacian

consists of functions \(\psi \in {{\widetilde{H}}}^{2n}(\Gamma )\) satisfying continuity and the Kirchhoff condition \(\sum _{x_j\in v}\partial \psi (x_j)=0\) at every vertex v: these vertex conditions for this operator are frequently referred to in the literature as (among other names) standard vertex conditions for \(\Gamma \) (see [45]). Note that representation (2.9) was used in [24], leading to interesting results.

3 n-Laplacians on Metric Graphs

An n -Laplacian on \(\Gamma \) is an operator in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) with differential expression \((-\Delta )^n\), where \(-\Delta :={\mathfrak {p}}^2=-\frac{\mathrm {d}^2}{\mathrm {d}x^2}\) and \(n\in {\mathbb {N}}\): it shall always be assumed that it has vertex conditions of the form (2.5). One may choose to assume in everything which follows that the n-Laplacians in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) respect the vertex structure of \(\Gamma \), except where explicitly stated otherwise. Our first task is to establish which vertex conditions lead to self-adjoint operators.

3.1 Self-Adjoint n-Laplacians

To establish which vertex conditions correspond to self-adjoint n-Laplacians, we define the minimal n -Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) to be the operator  which has differential expression \( (-\Delta )^n \) and domain given by

which has differential expression \( (-\Delta )^n \) and domain given by

This is the symmetric n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) with the smallest domain characterised by imposing vertex conditions on functions in \({{\widetilde{H}}}^{2n}(\Gamma )\). We refer to its adjoint  as the maximal n -Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\), having the same differential expression, but with the domain

as the maximal n -Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\), having the same differential expression, but with the domain  . Generically, neither of these operators respect the vertex structure of \(\Gamma \). Every self-adjoint n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) is an extension of

. Generically, neither of these operators respect the vertex structure of \(\Gamma \). Every self-adjoint n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) is an extension of  and a restriction of

and a restriction of  . To describe all such self-adjoint operators, one may use the formalism of boundary triples.

. To describe all such self-adjoint operators, one may use the formalism of boundary triples.

Given a symmetric operator  in a Hilbert space \({\mathfrak {H}}\), a boundary triple \(({\mathcal {H}},\varvec{\Gamma }_0,\varvec{\Gamma }_1)\) for

in a Hilbert space \({\mathfrak {H}}\), a boundary triple \(({\mathcal {H}},\varvec{\Gamma }_0,\varvec{\Gamma }_1)\) for  consists of a Hilbert space \({\mathcal {H}}\) called the boundary space, together with two boundary maps

consists of a Hilbert space \({\mathcal {H}}\) called the boundary space, together with two boundary maps  such that

such that

for some real constant c. The dimension of \({\mathcal {H}}\) must be equal to the defect index of  (Theorem 1.5, Ch. 3, [26]); for n-Laplacians in \(L_2(\Gamma )\), this will be nd.

(Theorem 1.5, Ch. 3, [26]); for n-Laplacians in \(L_2(\Gamma )\), this will be nd.

Proposition 3.1

(Theorem 1.6, Ch. 3, [26]). Let \(({\mathcal {H}},\varvec{\Gamma }_0,\varvec{\Gamma }_1)\) be a boundary triple for an operator  on a Hilbert space \({\mathfrak {H}}\). Then an extension

on a Hilbert space \({\mathfrak {H}}\). Then an extension  of

of  is self-adjoint if and only if there exists a \(\dim ({\mathcal {H}})\times \dim ({\mathcal {H}})\) unitary matrix \({\mathbb {U}}\) such that

is self-adjoint if and only if there exists a \(\dim ({\mathcal {H}})\times \dim ({\mathcal {H}})\) unitary matrix \({\mathbb {U}}\) such that  is the largest subset of

is the largest subset of  on which

on which

holds.

The sesquilinear boundary form for the n-Laplacian  is given by \(\Omega (\phi ,\psi )=\langle \phi , (-\Delta )^n \psi \rangle -\langle (-\Delta )^n \phi ,\psi \rangle \) for all

is given by \(\Omega (\phi ,\psi )=\langle \phi , (-\Delta )^n \psi \rangle -\langle (-\Delta )^n \phi ,\psi \rangle \) for all  . To derive an explicit expression, we define for each \(k\in {\mathbb {R}}\backslash \{0\}\) the boundary maps \(\varvec{\Gamma }_0(k),\varvec{\Gamma }_1(k): {{\widetilde{H}}}^{2n}(\Gamma )\rightarrow {\mathbb {C}}^{nd}\) by

. To derive an explicit expression, we define for each \(k\in {\mathbb {R}}\backslash \{0\}\) the boundary maps \(\varvec{\Gamma }_0(k),\varvec{\Gamma }_1(k): {{\widetilde{H}}}^{2n}(\Gamma )\rightarrow {\mathbb {C}}^{nd}\) by

Here, \( {\mathbb {C}}^{nd} \) is the boundary space. Integration by parts implies that

for  , independently of k. Thus, \(({\mathbb {C}}^{nd},\varvec{\Gamma }_0(k),\varvec{\Gamma }_1(k))\) is a boundary triple for

, independently of k. Thus, \(({\mathbb {C}}^{nd},\varvec{\Gamma }_0(k),\varvec{\Gamma }_1(k))\) is a boundary triple for  for any real \( k \ne 0\) .

for any real \( k \ne 0\) .

The following type of result is a standard ingredient in the theory of boundary triples. For Schrödinger operators on metric graphs, see Lemma 2.2, [34], equation (10), [29], Theorem 6, [36], and Theorem 2.6, [45]; these results are summarised in Theorem 1.4.4, [8]. Our theorem can be seen as a generalisation of these results in the Laplacian case, together with Theorem 3.1, [27] for bi-Laplacians, and Theorem 3.4, [15] for higher-order operators. Operators here are not required to respect the vertex structure of \(\Gamma \).

Theorem 3.2

Let  be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) with fixed vertex conditions. For any given \(k\in {\mathbb {R}}\backslash \{0\}\), let \(\varvec{\Gamma }_0(k),\varvec{\Gamma }_1(k): {{\widetilde{H}}}^{2n}(\Gamma )\rightarrow {\mathbb {C}}^{nd}\) be the boundary maps (3.1). Then, the following are equivalent:

be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) with fixed vertex conditions. For any given \(k\in {\mathbb {R}}\backslash \{0\}\), let \(\varvec{\Gamma }_0(k),\varvec{\Gamma }_1(k): {{\widetilde{H}}}^{2n}(\Gamma )\rightarrow {\mathbb {C}}^{nd}\) be the boundary maps (3.1). Then, the following are equivalent:

-

(a)

is self-adjoint;

is self-adjoint; -

(b)

there exists an \(nd\times nd\) unitary matrix \({\mathbb {U}}(k)\) such that

if and only if $$\begin{aligned} \mathrm {i}({\mathbb {U}}(k)-{\mathbb {I}})\varvec{\Gamma }_0(k) \psi =({\mathbb {U}}(k)+{\mathbb {I}})\varvec{\Gamma }_1(k)\psi ; \end{aligned}$$(3.3)

if and only if $$\begin{aligned} \mathrm {i}({\mathbb {U}}(k)-{\mathbb {I}})\varvec{\Gamma }_0(k) \psi =({\mathbb {U}}(k)+{\mathbb {I}})\varvec{\Gamma }_1(k)\psi ; \end{aligned}$$(3.3) -

(c)

there exist a subspace \(X\subseteq {\mathbb {C}}^{nd}\) and a Hermitian linear map \(T\in {\mathcal {L}}(X)\) such that

if and only if $$\begin{aligned} \varvec{\Gamma }_0(1)\psi \in X,\qquad \varvec{\Gamma }_1(1) \psi +T\varvec{\Gamma }_0(1)\psi \in X^\perp ; \end{aligned}$$(3.4)

if and only if $$\begin{aligned} \varvec{\Gamma }_0(1)\psi \in X,\qquad \varvec{\Gamma }_1(1) \psi +T\varvec{\Gamma }_0(1)\psi \in X^\perp ; \end{aligned}$$(3.4) -

(d)

there exist matrices \( A_0, A_1,\dots , A_{2n-1}\) of size \(nd\times d\) for which

$$\begin{aligned} \sum _{j=0}^{n-1}(-1)^j A_j A_{2n-1-j}^* \end{aligned}$$(3.5)is Hermitian and the concatenated matrix \(\left( A_0\Bigg | A_1\Bigg |\ldots \Bigg | A_{2n-1}\right) \) has maximal rank nd, such that

if and only if $$\begin{aligned} \sum _{s=0}^{2n-1} A_s\partial ^s\varvec{\Psi }=0. \end{aligned}$$(3.6)

if and only if $$\begin{aligned} \sum _{s=0}^{2n-1} A_s\partial ^s\varvec{\Psi }=0. \end{aligned}$$(3.6)

Proof

See “Appendix A.” \(\square \)

Remark

The concatenated matrix \(\left( A_0\Bigg | A_1\Bigg |\ldots \Bigg | A_{2n-1}\right) \) defining the vertex conditions (3.6) of a self-adjoint n-Laplacian is unique up to left multiplication by an invertible \(nd\times nd\) matrix.

Example 3.3

A bi-Laplacian  in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) is self-adjoint if and only if its vertex conditions can be written in the form \(A_0\varvec{\Psi }+A_1\partial \varvec{\Psi }+A_2\partial ^2\varvec{\Psi }+A_3\partial ^3\varvec{\Psi }=0\) for some \(2d\times d\) matrices \(A_0,A_1,A_2,A_3\) such that \(A_0A_3^*-A_1A_2^*\) is Hermitian and \(\text {rank}\left( A_0\Bigg |A_1\Bigg |A_2\Bigg |A_3\right) =2d\).

in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) is self-adjoint if and only if its vertex conditions can be written in the form \(A_0\varvec{\Psi }+A_1\partial \varvec{\Psi }+A_2\partial ^2\varvec{\Psi }+A_3\partial ^3\varvec{\Psi }=0\) for some \(2d\times d\) matrices \(A_0,A_1,A_2,A_3\) such that \(A_0A_3^*-A_1A_2^*\) is Hermitian and \(\text {rank}\left( A_0\Bigg |A_1\Bigg |A_2\Bigg |A_3\right) =2d\).

For any prescribed \(k\in {\mathbb {R}}\backslash \{0\}\), the unitary matrix \({\mathbb {U}}(k)\) serves as a parameter for all self-adjoint n-Laplacians in \(L_2(\Gamma )\). More precisely, writing  to avoid ambiguity, the map

to avoid ambiguity, the map  gives a bijection between the set of unitary \(nd\times nd\) matrices and the set of all self-adjoint n-Laplacians on graphs formed of the edges in E (not just those which respect the vertex structure). The unitary parameter can be computed explicitly using formula (A.5) in “Appendix A,” given the vertex conditions written in the form (3.6), and is a unitary matrix-valued holomorphic function of k. For Laplacians, \({\mathbb {U}}(k)\) is just the vertex scattering matrix from the existing literature (see [45]). For higher n, it serves as an analogue purely by virtue of equation (3.3), although is not itself a scattering matrix for the associated n-Laplacian in any rigorous physical or mathematical sense. The matrix which better fits that role is introduced in Sect. 4.2.

gives a bijection between the set of unitary \(nd\times nd\) matrices and the set of all self-adjoint n-Laplacians on graphs formed of the edges in E (not just those which respect the vertex structure). The unitary parameter can be computed explicitly using formula (A.5) in “Appendix A,” given the vertex conditions written in the form (3.6), and is a unitary matrix-valued holomorphic function of k. For Laplacians, \({\mathbb {U}}(k)\) is just the vertex scattering matrix from the existing literature (see [45]). For higher n, it serves as an analogue purely by virtue of equation (3.3), although is not itself a scattering matrix for the associated n-Laplacian in any rigorous physical or mathematical sense. The matrix which better fits that role is introduced in Sect. 4.2.

As in the Laplacian (\(n=1\)) case, the unitary parameter easily allows one to determine which endpoints are connected via the vertex conditions and therefore to understand whether the vertex conditions are consistent with the vertex structure or not. The vertices in the graph are determined by the irreducible decomposition of \( {\mathbb {U}}(k) \). More precisely, given a specific graph \(\Gamma \), the unitary matrices corresponding to self-adjoint n-Laplacians in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) are precisely those which have an irreducible block diagonal structure with respect to the vertices; that is to say, if we reorder the rows and columns of \({\mathbb {U}}(k)\) to group all boundary values of functions and derivatives at the same vertex together, then \({\mathbb {U}}(k)\) should be block diagonal, and it should not be possible to form smaller blocks by just permutations of endpoints. For instance, if the unitary matrix is irreducible, then all endpoints are joined together in a single vertex. In such a way, one can place restrictions on the unitary parameter so as to only parameterise self-adjoint n-Laplacians which preserve the vertex structure.

To ensure that in what follows we are dealing only with self-adjoint n-Laplacians in \(L_2(\Gamma )\), according to Theorem 3.2, we shall work from now on under the following assumption:

Assumption 3.4

The vertex conditions can be written in the form (3.3) for some \(k\in {\mathbb {R}}\backslash \{0\}\) and some \(nd\times nd\) unitary matrix \({\mathbb {U}}(k)\).

3.2 Elementary Spectral Properties

Having identified the self-adjoint Laplacians, our next goal is to analyse their spectra. Everything that follows concerns only compact graphs, with the exceptions of the constructions of the vertex transmission matrix and vertex scattering matrix in Sects. 4.1 and 4.2, respectively, which is valid even for finite non-compact graphs.

Given an operator  with a real, discrete spectrum which is bounded below, we shall denote its eigenvalues, counting multiplicities, by

with a real, discrete spectrum which is bounded below, we shall denote its eigenvalues, counting multiplicities, by  . For \(\lambda \in {\mathbb {R}}\), denote by

. For \(\lambda \in {\mathbb {R}}\), denote by  the eigenvalue counting function of

the eigenvalue counting function of  , that is the number of eigenvalues of

, that is the number of eigenvalues of  of value at most equal to \(\lambda \). Owing, in part, to the fact that finite rank perturbations in the resolvent sense preserve the discreteness of the spectrum, one deduces the following theorem; the reader is likely to be familiar with these results for other operators, for which reason the proof is deferred to “Appendix A.”

of value at most equal to \(\lambda \). Owing, in part, to the fact that finite rank perturbations in the resolvent sense preserve the discreteness of the spectrum, one deduces the following theorem; the reader is likely to be familiar with these results for other operators, for which reason the proof is deferred to “Appendix A.”

Theorem 3.5

Let  be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\), and suppose that \(\Gamma \) is compact. Under Assumption 3.4:

be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\), and suppose that \(\Gamma \) is compact. Under Assumption 3.4:

-

(i)

the spectrum of

is pure discrete;

is pure discrete; -

(ii)

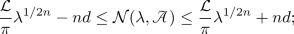

if E has d endpoints and total length \({\mathcal {L}}\), then for \(\lambda >0\),

(3.7)

(3.7) -

(iii)

the eigenvalues of

satisfy the Weyl law

satisfy the Weyl law  (3.8)

(3.8)as \(j\rightarrow \infty \).

Proof

See “Appendix A.” \(\square \)

4 Transmission Matrices and the Secular Equation for n-Laplacians

In the spectral theory of Laplace operators on metric graphs, the main ingredient of the scattering matrix approach to parameterising the vertex conditions is that solutions to the equation \(-\Delta \psi =k^2\psi \) on the edges can be written in a certain basis of incoming and outgoing waves: the corresponding amplitudes are related via the unitary vertex scattering matrix (see [35, 45]). For self-adjoint n-Laplacians, one may also introduce a \(d\times d\) vertex scattering matrix (see Sect. 4.2), but for \(n\ge 2\) it does not work as a parameter: vertex conditions are described by \( n^2 d^2 \) real parameters, whilst vertex scattering matrices contain just \( d^2 \) real parameters.

4.1 The Vertex Transmission Matrix

Let  be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) satisfying Assumption 3.4. Throughout the rest of this paper, write \(\omega :=\mathrm {e}^{\pi \mathrm {i}/n}\). Any function \(\psi \in {{\widetilde{H}}}^{2n}(\Gamma )\) which satisfies the formal differential equation

be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) satisfying Assumption 3.4. Throughout the rest of this paper, write \(\omega :=\mathrm {e}^{\pi \mathrm {i}/n}\). Any function \(\psi \in {{\widetilde{H}}}^{2n}(\Gamma )\) which satisfies the formal differential equation

on the edge \(e(x_j)\) can be written in the form

for some amplitudes \(a_j^l,b_j^l\in {\mathbb {C}}\) corresponding to the endpoint \(x_j\). The terms with amplitudes \(a_j^l\) serve as analogues of the incoming waves to the endpoint \(x_j\) (from the scattering theory of Laplacians), and in the same way, the terms with amplitudes \(b_j^l\) are the analogues of outgoing waves. Note that this analogy is purely formal since only the amplitudes with \(l=0\) actually correspond to plane waves. Writing the amplitudes as column vectors \({\mathbf {a}}^l:=\{a_j^l\}_{j=1}^d\) and \({\mathbf {b}}^l:=\{b_j^l\}_{j=1}^d\) for \(l=0,1,\dots ,n-1\), we can introduce a formal analogue of the vertex scattering matrix for general \(n\in {\mathbb {N}}\), called the vertex transmission matrix. This is defined to be the \(nd\times nd\) matrix \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}(k)\) such that a function \(\psi \), which for each j has the form (4.2) in x in a neighbourhood of \(x_j\), satisfies the vertex conditions of  if and only if the amplitudes solve

if and only if the amplitudes solve

Note that this definition takes into account the vertex conditions only, and so we consider the amplitudes independently of whether they correspond to different endpoints of the same edge. This is necessary in order to be able to determine \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}(k)\) uniquely. We may write  to avoid ambiguity.

to avoid ambiguity.

The matrix can be constructed explicitly as follows: let \(\psi \in L_2(\Gamma )\) be any function which in a neighbourhood of each vertex \(x_j\) has the form (4.2). Then from the vertex conditions (3.6), we get the system of equations

where the \(nd\times nd\) matrix \({\mathbb {Y}}(k)\) is defined for all \(k\in {\mathbb {C}}\) by

This matrix is clearly not unique for  , but the associated linear relation (4.4) is uniquely determined. Wherever \({\mathbb {Y}}(k)\) is invertible, we then have

, but the associated linear relation (4.4) is uniquely determined. Wherever \({\mathbb {Y}}(k)\) is invertible, we then have

In general, \(\det {\mathbb {Y}}(k)\) may have nonzero roots which could be real, and thus, \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}(k)\) may be not everywhere defined on \({\mathbb {R}}\). Denote by  the set of values of \(k\in {\mathbb {C}}\) at which \({\mathbb {Y}}(k)\) is not invertible; it contains all singularities of \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}(k)\), but it should be noted that some of these singularities may be removable. We shall show that this set is finite.

the set of values of \(k\in {\mathbb {C}}\) at which \({\mathbb {Y}}(k)\) is not invertible; it contains all singularities of \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}(k)\), but it should be noted that some of these singularities may be removable. We shall show that this set is finite.

Example 4.1

Consider the bi-Laplacian  in \(L_2([0,\infty ))\) with vertex conditions (3.6), where

in \(L_2([0,\infty ))\) with vertex conditions (3.6), where  ,

,  ,

,  . It follows from Example 3.3 that it is self-adjoint. The matrix (4.5) is

. It follows from Example 3.3 that it is self-adjoint. The matrix (4.5) is

Now, \(\det {\mathbb {Y}}(k)\) is a polynomial of degree five and has five distinct roots forming the set  . It is clear for instance that

. It is clear for instance that  , and one finds that this is a singularity of \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}\) which is not removable.

, and one finds that this is a singularity of \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}\) which is not removable.

Lemma 4.2

Let  be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\). Under Assumption 3.4,

be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\). Under Assumption 3.4,

-

(i)

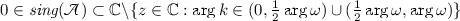

if \(k\in {\mathbb {C}}\backslash \{0\}\), then

if and only if there exists a non-trivial solution of (4.4) with \({\mathbf {b}}^l={\mathbf {0}}\) for all \(l=0,\dots , n-1\);

if and only if there exists a non-trivial solution of (4.4) with \({\mathbf {b}}^l={\mathbf {0}}\) for all \(l=0,\dots , n-1\); -

(ii)

,

, -

(iii)

.

.

Proof

-

(i):

For \(k\ne 0\), the matrix \({\mathbb {Y}}(k)\) is not invertible if and only if there exists a nonzero vector \({\mathbf {a}}\) such that \({\mathbb {Y}}(k){\mathbf {a}}={\mathbf {0}}\).

-

(ii):

It is clear from (4.5) that

. Consider the d-star graph and on it the n-Laplacian with vertex conditions determined by

. Consider the d-star graph and on it the n-Laplacian with vertex conditions determined by  . Suppose for a contradiction that

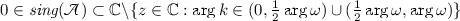

. Suppose for a contradiction that  is such that \(\arg k\in (0,\frac{1}{2}\arg \omega )\cup (\frac{1}{2}\arg \omega ,\arg \omega )\). Now, part (i) implies that there exists a vector \({\mathbf {a}} \) satisfying (4.4) with \( {\mathbf {b}}={\mathbf {0}}. \) By assumption, \(\mathfrak {Re}[\mathrm {i}\omega ^lk]<0\) for all \(l=0,\dots ,n-1\), so every \(\psi \) decays exponentially along every half line (it is not identically zero on at least one of these). Thus, \(\psi \) is an eigenfunction of the n-Laplacian operator on the d-star graph with the aforementioned vertex conditions. But by self-adjointness, the spectrum of this operator is real, and so, we get a contradiction since \(k^{2n}\notin {\mathbb {R}}\).

is such that \(\arg k\in (0,\frac{1}{2}\arg \omega )\cup (\frac{1}{2}\arg \omega ,\arg \omega )\). Now, part (i) implies that there exists a vector \({\mathbf {a}} \) satisfying (4.4) with \( {\mathbf {b}}={\mathbf {0}}. \) By assumption, \(\mathfrak {Re}[\mathrm {i}\omega ^lk]<0\) for all \(l=0,\dots ,n-1\), so every \(\psi \) decays exponentially along every half line (it is not identically zero on at least one of these). Thus, \(\psi \) is an eigenfunction of the n-Laplacian operator on the d-star graph with the aforementioned vertex conditions. But by self-adjointness, the spectrum of this operator is real, and so, we get a contradiction since \(k^{2n}\notin {\mathbb {R}}\). -

(iii):

By definition (4.5), it follows that \(\det {\mathbb {Y}}(k)\) is a polynomial of degree at most \((n-1)^{nd}\). By part (ii), \(\det {\mathbb {Y}}(k)\not \equiv 0\), and thus, it has at most \((n-1)^{nd}\) roots.

\(\square \)

Remark

Given a bi-Laplacian  in \(L_2(\Gamma )\), one can show that for

in \(L_2(\Gamma )\), one can show that for  , the operator

, the operator  is self-adjoint if and only if

is self-adjoint if and only if  for some matrices \({\mathbf {S}},{\mathbf {B}},{\mathbf {C}},{\mathbf {D}}\) such that \({\mathbf {S}}{\mathbf {S}}^*={\mathbf {I}}\), \({\mathbf {S}}{\mathbf {C}}^*=\mathrm {i}{\mathbf {B}}\) and \({\mathbf {C}}{\mathbf {C}}^*=\mathrm {i}({\mathbf {D}}-{\mathbf {D}}^*)\). In principle, this can be generalised to parameterise higher-order n-Laplacians by \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}(k)\), but \({\mathbb {U}}(k)\) is a much more convenient parameter.

for some matrices \({\mathbf {S}},{\mathbf {B}},{\mathbf {C}},{\mathbf {D}}\) such that \({\mathbf {S}}{\mathbf {S}}^*={\mathbf {I}}\), \({\mathbf {S}}{\mathbf {C}}^*=\mathrm {i}{\mathbf {B}}\) and \({\mathbf {C}}{\mathbf {C}}^*=\mathrm {i}({\mathbf {D}}-{\mathbf {D}}^*)\). In principle, this can be generalised to parameterise higher-order n-Laplacians by \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}(k)\), but \({\mathbb {U}}(k)\) is a much more convenient parameter.

4.2 The Vertex Scattering Matrix

Given an n-Laplacian  in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) satisfying Assumption 3.4, denote by \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}(k)\) the upper left \(d\times d\) block of \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}(k)\):

in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) satisfying Assumption 3.4, denote by \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}(k)\) the upper left \(d\times d\) block of \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}(k)\):

This is the matrix which relates the amplitudes \({\mathbf {a}}^0\) and \({\mathbf {b}}^0\) of classical incoming and outgoing plane waves \(\mathrm {e}^{\mathrm {i}k|x-x_j|}\) and \(\mathrm {e}^{-\mathrm {i}k|x-x_j|}\), respectively. We refer to \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}(k)\) as the vertex scattering matrix of  . If there is ambiguity, we may write it as

. If there is ambiguity, we may write it as  . One can show that it is unitary on \({\mathbb {R}}\) and is thus defined even when \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}(k)\) is not: since each entry of \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}(k)\) is then a bounded rational function of k on

. One can show that it is unitary on \({\mathbb {R}}\) and is thus defined even when \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}(k)\) is not: since each entry of \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}(k)\) is then a bounded rational function of k on  , it can be extended to all of \({\mathbb {R}}\) by taking limits. The proof of this is elementary but messy, so we defer it to “Appendix B.”

, it can be extended to all of \({\mathbb {R}}\) by taking limits. The proof of this is elementary but messy, so we defer it to “Appendix B.”

Theorem 4.3

Let  be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\). Under Assumption 3.4, the vertex scattering matrix \({\mathbf {S}}_v (k)\) is unitary for all \(k\in {\mathbb {R}}\).

be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\). Under Assumption 3.4, the vertex scattering matrix \({\mathbf {S}}_v (k)\) is unitary for all \(k\in {\mathbb {R}}\).

Proof

See “Appendix B.” \(\square \)

This fact is not surprising since the vertex scattering matrix as we define it coincides with the scattering matrix from the mathematical scattering theory (see [57]) for a certain pair of operators on the non-compact star graph with different vertex conditions. This matrix will play a key role in analysing the spectral asymptotics (see Sect. 6). In the case of the bi-Laplacian (\(n=2\)) for instance, given a physical network of beams, it should be possible to measure \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}(k)\) for certain values of k by generating plane waves far along each beam and measuring how these are scattered: for solutions with \({\mathbf {b}}^1 = {\mathbf {0}}\), we have \({\mathbf {a}}^0={\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}(k){\mathbf {b}}^0\). However, unlike in the Laplacian case, in general for \(n\ge 2\), knowledge of \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}(k)\) alone is not sufficient to determine the vertex conditions. Nevertheless, if one can be sure that the vertex conditions are scaling-invariant (Sect. 5), then one can determine a lot more about the vertex conditions from \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}(k)\) (e.g. Corollary 5.4) even though we shall see that for such conditions the matrix is constant.

4.3 The Edge Transmission Matrix

Let  be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) satisfying Assumption 3.4, and suppose, as we shall for the remainder of the paper, that all \(N=d/2\) edges are compact. A function \( \psi \) is an eigenfunction of

be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) satisfying Assumption 3.4, and suppose, as we shall for the remainder of the paper, that all \(N=d/2\) edges are compact. A function \( \psi \) is an eigenfunction of  if and only if it satisfies the differential equation (4.1) on the edges, together with the vertex conditions. Every such function can be written as (4.2) for all \(x\in e(x_j)\). The amplitudes \(a_j^l, b_j^l\) are not independent: one connection comes from the vertex conditions (c.f. (4.3)); the other comes from the edges. On each (compact) edge, \(\psi \) has two expressions, one associated with each endpoint. These expressions match if and only if

if and only if it satisfies the differential equation (4.1) on the edges, together with the vertex conditions. Every such function can be written as (4.2) for all \(x\in e(x_j)\). The amplitudes \(a_j^l, b_j^l\) are not independent: one connection comes from the vertex conditions (c.f. (4.3)); the other comes from the edges. On each (compact) edge, \(\psi \) has two expressions, one associated with each endpoint. These expressions match if and only if

for all \(j=1,\dots ,N=d/2\), where \(\ell _j\) is the length of edge \(e_j\) (c.f., for example, [28]). This can be encoded into an \(nd\times nd\) matrix \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {e}(k)\) (like the edge scattering matrix for Laplacians, c.f. [45]) such that the expressions match if and only if

We refer to \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {e}(k)\) as the edge transmission matrix corresponding to the set of edges E. It is independent of the vertex conditions of  and hence also independent of the topology of the induced graph

and hence also independent of the topology of the induced graph  . It is clear from (4.8) that this matrix is given explicitly by

. It is clear from (4.8) that this matrix is given explicitly by

where

and \(\Lambda :=\text {diag}(\ell _1,\dots ,\ell _N)\) is the diagonal matrix whose nonzero entries are the lengths of the (compact) edges. Comparing with [45], we see that \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {e}(k)\) is precisely the edge scattering matrix for Laplacians on the same set E of edges.

4.4 The Secular Equation

Theorem 4.4

Let  be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\), and suppose that all of the edges in E are compact. Under Assumption 3.4, nonzero spectrum of

be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\), and suppose that all of the edges in E are compact. Under Assumption 3.4, nonzero spectrum of  is given by the set of solutions \(\lambda =k^{2n}\) to the equation

is given by the set of solutions \(\lambda =k^{2n}\) to the equation

where \({\mathbb {Y}}(k)\) is expressed as (4.5) in terms of the vertex conditions (3.6), and the geometric multiplicity of \(\lambda \) equals the dimension of \(\ker [{\mathbb {Y}}(k)+{\mathbb {Y}}(-k){\mathbb {T}}_\text {e}(k)]\). Those values of k that are not in  are equivalently the solutions of

are equivalently the solutions of

Proof

We saw in Sect. 4.1 that a nonzero function \(\psi \) of the form (4.2) in a neighbourhood of each endpoint \(x_j\) satisfies the vertex conditions of  if and only if the amplitudes satisfy (4.4). Moreover, as all edges are compact, we saw in Sect. 4.2 that (4.9) must hold. Thus, \(\psi \) is an eigenvector of

if and only if the amplitudes satisfy (4.4). Moreover, as all edges are compact, we saw in Sect. 4.2 that (4.9) must hold. Thus, \(\psi \) is an eigenvector of  if and only if both of these hold, equivalently, if and only if

if and only if both of these hold, equivalently, if and only if

A non-trivial vector solution of this equations exists if and only if k solves (4.12). In other words, \(\lambda \ne 0\) is an eigenvalue of  if and only \(\lambda =k^{2n}\) for some solution k of (4.12) which one may assume without loss of generality is such that \(\arg k\in [0,\pi /n)\).

if and only \(\lambda =k^{2n}\) for some solution k of (4.12) which one may assume without loss of generality is such that \(\arg k\in [0,\pi /n)\).

It remains only to check multiplicities. On each edge \(e_j\), where \(j=1,\dots ,N\) (\(=d/2\)), there is a bijection between the amplitudes \(a_j^0\dots ,a_j^{n-1},b_j^0,\dots ,b_j^{n-1}\) and solutions of the eigenvalue problem \((-\Delta )^n\psi _j=\lambda \psi _j\) on that edge. Moreover, it follows from the relations (4.8) that there is a bijective correspondence between the amplitudes \(a_j^0,a_{j+N}^0,\dots ,a_j^{n-1},a_{j+N}^{n-1}\) associated with that edge and the solutions of the eigenvalue problem along that edge via (4.2). Hence, the vector solutions of equation (4.14) for fixed \(\arg k\) are in bijection with the \(\lambda =k^{2n}\) eigenstates of the n-Laplacian. \(\square \)

Example 4.5

Consider the bi-Laplacian  in \(L_2([0,\ell ])\) with the same vertex conditions as the operator from Example 4.1, but now applied at both endpoints. One has

in \(L_2([0,\ell ])\) with the same vertex conditions as the operator from Example 4.1, but now applied at both endpoints. One has

The nonzero eigenvalues are then the values \(k^2\) for which k solves (4.12). It follows from Example 4.1 that \(k=1\) is an irremovable singularity of \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}(k)\) for this operator as well. However, one finds that if \(\ell =\pi \), then \(k=1\) will be a root of (4.12). Hence, in this case, one could not pick up the eigenvalue 1 using the alternative equation (4.13).

Equation (4.13) serves as a secular equation for  , although the finite number of possible instances where solutions of (4.12) coincide with singularities of \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}(k)\) must be taken into account. It is a generalisation of the secular equation for self-adjoint Laplacians

, although the finite number of possible instances where solutions of (4.12) coincide with singularities of \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}(k)\) must be taken into account. It is a generalisation of the secular equation for self-adjoint Laplacians  which has the form \(\det [{\mathbf {I}}-{\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}(k){\mathbf {S}}_\text {e}(k)]=0\), where \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}(k)\) and \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {e}(k)\) are the vertex scattering matrix and the edge scattering matrix respectivey for

which has the form \(\det [{\mathbf {I}}-{\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}(k){\mathbf {S}}_\text {e}(k)]=0\), where \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}(k)\) and \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {e}(k)\) are the vertex scattering matrix and the edge scattering matrix respectivey for  (see, for example, [28, 35, 44]). Much more can be said about the spectrum of

(see, for example, [28, 35, 44]). Much more can be said about the spectrum of  in the case that \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}\) is independent of k—corresponding to so-called scaling-invariant vertex conditions—which is largely due to the fact that in this case, the determinant is a trigonometric polynomial (see, for example, [47]). It would then be a natural step to study the n-Laplacians whose vertex conditions are such that \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}\) is independent of k. In that case,

in the case that \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}\) is independent of k—corresponding to so-called scaling-invariant vertex conditions—which is largely due to the fact that in this case, the determinant is a trigonometric polynomial (see, for example, [47]). It would then be a natural step to study the n-Laplacians whose vertex conditions are such that \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}\) is independent of k. In that case,  so equation (4.13) would give all of the (nonzero) eigenvalues of

so equation (4.13) would give all of the (nonzero) eigenvalues of  .

.

Remark

Whilst one could similarly derive a secular equation in terms of the unitary parameter \({\mathbb {U}}\), thereby avoiding the issue of singularities, the corresponding (non-unitary) matrix for the edges is less versatile than \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {e}\) due to the particular choice of basis of solutions of (4.1) needed (c.f. “Appendix B”).

5 Scaling-Invariant Vertex Conditions

Definition

The vertex conditions of differential operator in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) are called scaling-invariant if and only if, for any \(c>0\), \( \psi (x) \) satisfies the vertex conditions on \(\Gamma \) whenever \(\psi (cx)\) does on \(c\Gamma \).

Scaling-invariant vertex conditions have the characterising property that \(\lambda \) is an eigenvalue of an n-Laplacian on E with such conditions if and only if \(c^{2n}\lambda \) is an eigenvalue of the n-Laplacian on cE with the same vertex conditions.

Given an n-Laplacian  in \(L_2(\Gamma )\), not necessarily self-adjoint, its vertex conditions (2.5) are scaling-invariant (i.e. hold independently of the choice of scaling \(c>0\)) if and only if they can equivalently be written

in \(L_2(\Gamma )\), not necessarily self-adjoint, its vertex conditions (2.5) are scaling-invariant (i.e. hold independently of the choice of scaling \(c>0\)) if and only if they can equivalently be written

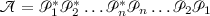

Thus,  is a product of first-order differential operators, and in the notation of Sect. 2.2, it can be expressed as

is a product of first-order differential operators, and in the notation of Sect. 2.2, it can be expressed as

On the other hand, any operator of this form is an n-Laplacian with scaling-invariant vertex conditions. We seek the subset of these which are also self-adjoint.

Remark

For Laplacians (\(n=1\)), the vertex conditions are scaling-invariant if and only if the so-called Robin part of the associated quadratic form vanishes (Theorem 2.1.6, [8]): these are precisely the Laplacians which can be written as a product of a first-order operator and its adjoint. More generally, we claim (though shall not prove in this paper) that self-adjoint n-Laplacians with non-Robin vertex conditions are those which can be written in the form  for some nth derivative operator

for some nth derivative operator  . Then the following theorem will imply that for \(n\ge 2\) scaling-invariant vertex conditions do not give all non-Robin n-Laplacians.

. Then the following theorem will imply that for \(n\ge 2\) scaling-invariant vertex conditions do not give all non-Robin n-Laplacians.

Theorem 5.1

Let  be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) with vertex conditions (3.6) and let \(k\in {\mathbb {R}}\backslash \{0\}\). Under Assumption 3.4, the following are equivalent:

be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) with vertex conditions (3.6) and let \(k\in {\mathbb {R}}\backslash \{0\}\). Under Assumption 3.4, the following are equivalent:

-

(a)

has scaling-invariant vertex conditions,

has scaling-invariant vertex conditions, -

(b)

for some first-order differential operators

for some first-order differential operators  in \(L_2(\Gamma )\),Footnote 3

in \(L_2(\Gamma )\),Footnote 3 -

(c)

\( A_0 A_{2n-1}^*= A_1 A_{2n-2}^*=\dots = A_{n-1} A_n^*=0\),

-

(d)

\({\mathbb {U}}\) is independent of k,

-

(e)

\({\mathbb {T}}_v \) is independent of k,

-

(f)

there exist \(d\times d\) unitary Hermitian matrices \({\mathbf {U}}_1,\dots ,{\mathbf {U}}_n\) such that

$$\begin{aligned} {\mathbb {U}}(k)=\begin{pmatrix}{\mathbf {U}}_1&{}\quad 0&{}\quad \ldots &{}\quad 0\\ 0&{}\quad -{\mathbf {U}}_2&{}\quad \ldots &{}\quad 0\\ \vdots &{}\quad \vdots &{}\quad \ddots &{}\quad \vdots \\ 0&{}\quad 0&{}\quad \ldots &{}\quad (-1)^{n-1}{\mathbf {U}}_n\end{pmatrix}. \end{aligned}$$(5.2)

In this case, \({\mathbf {U}}_j\) is the vertex scattering matrix of the Laplacian

Proof

(a)\(\Leftrightarrow \)(b)\(\Leftrightarrow \)(c): Recall that  has scaling-invariant vertex conditions if and only if the operator can be decomposed in the following way:

has scaling-invariant vertex conditions if and only if the operator can be decomposed in the following way:

in the notation of Sect. 2.2. Then  is self-adjoint and scaling-invariant if and only if additionally

is self-adjoint and scaling-invariant if and only if additionally  for all j, which by Lemma 2.1 is if and only if \( A_j A_{2n-1-j}^*=0\) (and \(\text {rank}( A_j)+\text {rank}( A_{2n-1-j})=d\)).

for all j, which by Lemma 2.1 is if and only if \( A_j A_{2n-1-j}^*=0\) (and \(\text {rank}( A_j)+\text {rank}( A_{2n-1-j})=d\)).

(c)\(\Rightarrow \)(d),(f): The vertex conditions can be written \({\mathbb {A}}(k)\varvec{\Gamma }_0(k)\psi ={\mathbb {B}}(k)\varvec{\Gamma }_1(k)\psi \) for each \(k\in {\mathbb {R}}\backslash \{0\}\), where \({\mathbb {A}}(k),{\mathbb {B}}(k)\) are defined by (A.2) in the proof of Theorem 3.2. If (c) holds, then one can assume without loss of generality that the \({\mathbb {A}}(k),{\mathbb {B}}(k)\) are block diagonal with blocks of size \(d\times d\), and in particular, \({\mathbb {A}}(k){\mathbb {B}}(k)^*=0\). But since these vertex conditions are also equivalent to (3.3), there exists \({\mathbb {X}}\in \text {GL}(nd)\) such that \({\mathbb {X}}{\mathbb {A}}(k)=\mathrm {i}({\mathbb {U}}(k)-{\mathbb {I}})\) and \({\mathbb {X}}{\mathbb {B}}(k)={\mathbb {U}}(k)+{\mathbb {I}}\). Then \({\mathbb {A}}(k){\mathbb {B}}(k)^*=0\) implies that \({\mathbb {U}}(k)={\mathbb {U}}(k)^*\). It then follows from (A.5) that \({\mathbb {U}}(k)\) has the form (5.2). Moreover, (c) implies that in fact (A.3) and (A.4) hold for all (complex) \(k\in {\mathbb {C}}\backslash \{0\}\), whence \({\mathbb {U}}(k)\) is unitary for all \(k\in {\mathbb {C}}\), and by (A.5), it is holomorphic. Liouville’s theorem then implies that it must be constant.

(d)\(\Leftrightarrow \)(e): See Corollary B.2.

(d)\(\Rightarrow \)(a): By Theorem 3.2, the vertex conditions can be written in the form \(\mathrm {i}({\mathbb {U}}(k)-{\mathbb {I}})\varvec{\Gamma }_0(k) \psi =({\mathbb {U}}(k)+{\mathbb {I}})\varvec{\Gamma }_1(k)\psi \) for every \(k\in {\mathbb {R}}\backslash \{0\}\). If \({\mathbb {U}}\) is independent of k, then this implies that \({\mathbb {U}}\) must be block diagonal, consisting of blocks of size \(d\times d\), and that in fact \(\mathrm {i}({\mathbb {U}}-{\mathbb {I}})\varvec{\Gamma }_0(k)\psi =({\mathbb {U}} +{\mathbb {I}})\varvec{\Gamma }_1(k)\psi =0\) for all \(k\in {\mathbb {R}}\backslash \{0\}\). Hence, the vertex conditions are scaling-invariant (c.f. (5.1)).

(f)\(\Rightarrow \)(a): If \({\mathbb {U}}(k)\) is of the form (5.2), then it is clear from the fact that the vertex conditions can be written in the form (3.3) that they are scaling-invariant (c.f. (5.1)).

Finally, suppose that any and thus all of the above hold. Then we have  for some first-order operators

for some first-order operators  . Now, the vertex conditions for

. Now, the vertex conditions for  can be written explicitly as

can be written explicitly as

and the non-Robin Laplacians  have vertex conditions

have vertex conditions

respectively. Thus, \({\mathbf {U}}_1,{\mathbf {U}}_2,{\mathbf {U}}_3,\dots \) must be their respective vertex scattering matrices (c.f. Theorem 3.2, or specifically for Laplacians: Theorem 2.1 in [45]). \(\square \)

Example 5.2

Let \(\Gamma \) be a compact finite metric graph with vertices V, and let  be the bi-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) with vertex conditions:

be the bi-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) with vertex conditions:

for all vertices \(v_m\in V\). Note that no conditions are imposed on the second derivates. This operator is the Friedrichs extension of the symmetric operator whose only conditions are continuity of functions at the vertices of \(\Gamma \) (see Example 4.5 in [27]). Clearly these vertex conditions are scaling-invariant: in particular  using the notation from Sect. 2.2. The unitary parameter for

using the notation from Sect. 2.2. The unitary parameter for  is

is

where \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {st}\) is the vertex scattering matrix for the standard Laplacian  mentioned in Sect. 2.2.

mentioned in Sect. 2.2.

The remainder of the paper is focused on the situation in which the vertex transmission matrix \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}\) is independent of k. To ensure that this is the case, according to Theorem 5.1, we shall work with n-Laplacians satisfying Assumption 3.4 together with the following:

Assumption 5.3

The vertex conditions are scaling-invariant, and all edges are compact.

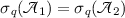

For bi-Laplacians satisfying these assumptions, one can establish the following relationship between the unitary parameter \({\mathbb {U}}\) and the vertex scattering matrix \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}\). It can be generalised for higher-order operators, but the computations become more involved so we do not present that here.

Corollary 5.4

Let  be a bi-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) satisfying Assumptions 3.4 and 5.3. Let \({\mathbf {S}}_v \) be the vertex scattering matrix for

be a bi-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) satisfying Assumptions 3.4 and 5.3. Let \({\mathbf {S}}_v \) be the vertex scattering matrix for  , and let \({\mathbf {U}}_1\) and \(-{\mathbf {U}}_2\) be the unitary Hermitian diagonal blocks of the unitary parameter \({\mathbb {U}}\) as given by (5.2). Then \(\mathrm {i}{\mathbf {I}}+{\mathbf {S}}_v \) is invertible, and

, and let \({\mathbf {U}}_1\) and \(-{\mathbf {U}}_2\) be the unitary Hermitian diagonal blocks of the unitary parameter \({\mathbb {U}}\) as given by (5.2). Then \(\mathrm {i}{\mathbf {I}}+{\mathbf {S}}_v \) is invertible, and

In particular, \({\mathbf {S}}_v \) is the vertex scattering matrix for a self-adjoint scaling-invariant bi-Laplacian if and only if there exist unitary Hermitian matrices \({\mathbf {U}}_1\) and \({\mathbf {U}}_2\) such that \({\mathbf {S}}_v =\mathrm {i}\{2{\mathbf {I}}+\mathrm {i}({\mathbf {U}}_1 +{\mathbf {U}}_2)\}^{-1}\{2{\mathbf {I}}-\mathrm {i}({\mathbf {U}}_1+{\mathbf {U}}_2)\}\). It is determined uniquely by the sum \({\mathbf {U}}_1+{\mathbf {U}}_2\) and thus corresponds to every bi-Laplacian with unitary Hermitian parameter  such that (5.3) holds. Moreover:

such that (5.3) holds. Moreover:

-

(i)

\({\mathbf {S}}_v ={\mathbf {S}}_v ^*\) if and only if \({\mathbf {U}}_1={\mathbf {U}}_2\), and in this case \({\mathbf {S}}_v ={\mathbf {U}}_1={\mathbf {U}}_2\),

-

(ii)

\({\mathbf {S}}_v =\mathrm {i}{\mathbf {I}}\) if and only if \({\mathbf {U}}_1=-{\mathbf {U}}_2\).

Proof

See “Appendix B.” \(\square \)

Remark

If \({\mathbf {U}}_1\) and \({\mathbf {U}}_2\) are unitary Hermitian matrices, then \(({\mathbf {U}}_1-{\mathbf {U}}_2)^2=4{\mathbf {I}} -({\mathbf {U}}_1+{\mathbf {U}}_2)^2\). Hence, one can use equation (5.3) to compute \(({\mathbf {U}}_1-{\mathbf {U}}_2)^2\) in terms of \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}\). However, in general this is not sufficient to obtain \({\mathbf {U}}_1\) and \({\mathbf {U}}_2\), and so, \( {\mathbf {S}}_\text {v} \) does not uniquely determine the corresponding bi-Laplacian.

6 The Secular Equation for Scaling-Invariant Vertex Conditions

6.1 More on the Secular Equation

For an n-Laplacian  in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) satisfying Assumptions 3.4 and 5.3, the vertex transmission matrix \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}\) is independent of k (Theorem 5.1), in which case the ‘secular equations’ (4.12) and (4.13) from Theorem 4.4 are completely equivalent. We thus refer to the function

in \(L_2(\Gamma )\) satisfying Assumptions 3.4 and 5.3, the vertex transmission matrix \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}\) is independent of k (Theorem 5.1), in which case the ‘secular equations’ (4.12) and (4.13) from Theorem 4.4 are completely equivalent. We thus refer to the function

as the secular function for  , and the equation \(\chi =0\) as the secular equation.

, and the equation \(\chi =0\) as the secular equation.

Let us decompose the transmission matrices \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}\) and \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {e}(k)\) into blocks in the following way:

The \((n-1)d\times (n-1)d\) matrix \({\tilde{T}}_\text {e}(k)\) consists of sub-blocks of the form \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {e}(\omega ^lk)\) for \(l\ge 1\), where we recall that \(\omega :=\mathrm {e}^{\pi \mathrm {i}/n}\). This means that if \(n\ge 2\), then the secular function is in general not a trigonometric polynomial like it is for Laplacians. The upside is that only \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {e}(k)\) has much influence on the secular equation for large k since \( {\tilde{T}}_\text {e}(k)\rightarrow 0\) exponentially as \(k\rightarrow \infty \). Indeed, dividing \(\chi (k)\) by an appropriate function (see Lemma 6.1) we get

where  . One needs to be careful in specifying where F is well defined, but then equation \(F=0\) is almost equivalent to the secular equation:

. One needs to be careful in specifying where F is well defined, but then equation \(F=0\) is almost equivalent to the secular equation:

Lemma 6.1

Let  be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\). Under Assumptions 3.4 and 5.3, for any \(\theta \in (0,\frac{\pi }{n})\), there exists \(\gamma _\theta \ge 0\) such that the function F is well defined in the sector \(\{z\in {\mathbb {C}}:|\arg (z-\gamma _\theta )|<\theta \}\), and has the same roots as the secular function \(\chi \) counting multiplicities.

be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\). Under Assumptions 3.4 and 5.3, for any \(\theta \in (0,\frac{\pi }{n})\), there exists \(\gamma _\theta \ge 0\) such that the function F is well defined in the sector \(\{z\in {\mathbb {C}}:|\arg (z-\gamma _\theta )|<\theta \}\), and has the same roots as the secular function \(\chi \) counting multiplicities.

Proof

For \(l=1,\dots ,n-1\), we have \(|\mathrm {e}^{\mathrm {i}\omega ^lk}|=\mathrm {e}^{-|k|\sin (\frac{\pi l}{n}+\arg k)}\le \mathrm {e}^{-|k|\sin (\frac{\pi }{n}-\theta )}\) on the sector \(|\arg k|<\theta \). Then \({\tilde{T}}_\text {e}(k)\) consists of exponentially decreasing blocks \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {e}(\omega ^lk)\) for \(l=1,\dots ,n-1\), so as \({\tilde{T}}_\text {v}\) is independent of k, there certainly exists \(\gamma _\theta >0\) such that the function

is bounded below by \(\frac{1}{2}\) on the shifted sector \(|\arg (z-\gamma _\theta )|\le \theta \) and thus has no zeros there. Then \({\mathbf {X}}(k)\) is well defined in this sector, and hence so is F. Since \(\chi (k)=F(k){\tilde{F}}(k)\), the result follows. \(\square \)

6.2 The Associated Trigonometric Polynomial and Dirac Operator

Due to the exponentially decreasing nature of the matrix \({\mathbf {X}}(k)\), the function F(k) is in some sense very close to the trigonometric polynomial

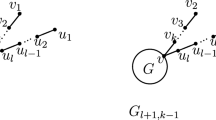

This looks very much like the secular function for a self-adjoint Laplacian, but in general this is not the case: despite being a constant unitary matrix, \({\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}\) is not necessarily Hermitian (c.f. Theorem 2.1.6, [8]). For instance, by Corollary 5.4, the scattering matrix for a self-adjoint bi-Laplacian with scaling-invariant conditions is Hermitian if and only if  is the square of a Laplacian. Nevertheless, the equation \(G=0\) is still the secular equation of a self-adjoint differential operator: given a \(d\times d\) unitary matrix \({\mathbf {U}}\), consider the Dirac operator

is the square of a Laplacian. Nevertheless, the equation \(G=0\) is still the secular equation of a self-adjoint differential operator: given a \(d\times d\) unitary matrix \({\mathbf {U}}\), consider the Dirac operator

Its spectrum is given by the roots of the secular function \(\det [{\mathbf {I}}-{\mathbf {U}}{\mathbf {S}}_\text {e}(k)]\). In the case that \({\mathbf {U}}:={\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}\) (6.5) is its secular function.

As G is a trigonometric polynomial with fewer terms, its roots are easier to compute than those of F, and one would hope to be able to use them to asymptotically approximate the eigenvalues of  . More precisely, one would expect that the roots of F become asymptotically closer to the roots of G. To prove such a result for two functions f and g, we would need to compute integrals of \(f'/f-g'/g\) along progressively smaller contours around more and more distant roots, and show that these are zero. One would therefore hope that they satisfy

. More precisely, one would expect that the roots of F become asymptotically closer to the roots of G. To prove such a result for two functions f and g, we would need to compute integrals of \(f'/f-g'/g\) along progressively smaller contours around more and more distant roots, and show that these are zero. One would therefore hope that they satisfy

for some appropriate (unbounded) open set \({\mathcal {U}}\). The sort of ‘appropriate set’ that we shall work with is what we refer to as a right half strip, namely anything of the form

for \(a,b,\gamma \in {\mathbb {R}}\).

Definition

If g is a trigonometric polynomial, or more generally an almost periodic function, then we shall refer to any holomorphic function f satisfying (6.7) as a holomorphic perturbation of g on \({\mathcal {U}}\).

For a complete proof of convergence of the roots of such functions, we need some results from the theory of almost periodic functions (see Sect. 7). The next lemma ensures that this theory would indeed be applicable to F and G.

Lemma 6.2

Let  be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\). Under Assumptions 3.4 and 5.3, the function

be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\). Under Assumptions 3.4 and 5.3, the function  is a holomorphic perturbation of

is a holomorphic perturbation of  on any right half strip \({\mathcal {U}}\).

on any right half strip \({\mathcal {U}}\).

Proof

Fix \(\theta \in (0,\frac{\pi }{n})\). It is sufficient to prove this result for any half strip which is contained in the sector \(\{z\in {\mathbb {C}}:|\arg (z-\gamma _\theta )|\le \theta \}\); recall from Lemma 6.1 that \(\gamma _\theta \ge 0\) was chosen such that the function \({\tilde{F}}\) defined by (6.4) satisfies \(|{\tilde{F}}|\ge \frac{1}{2}\) here.

Let \({\mathcal {Q}}\) be the following set of holomorphic functions defined on this sector:

where \({\mathbb {H}}_+\) denotes the upper half plane. Observe that \({\mathcal {Q}}\) is invariant under differentiation and multiplication by trigonometric polynomials. Given some \(h(k)={\tilde{F}}(k)^{-a}\sum _{m=1}^Mc_m\mathrm {e}^{\mathrm {i}\zeta _mk}\in {\mathcal {Q}}\), as \(\mathfrak {Im}\,k\) is bounded on \({\mathcal {U}}\) there exists a constant \(C_{h}>0\) such that \(|\mathrm {e}^{\mathrm {i}(\mathfrak {Re}\,\zeta _m)k}|=\mathrm {e}^{-(\mathfrak {Re}\,\zeta _m)\mathfrak {Im}\,k}\le C_{h}\) for \(m=1,\dots ,M\) whenever \(k\in {\mathcal {U}}\). Then \(|h(k)|\le 2^aC_{h}\sum _{m=1}^M |c_m| \mathrm {e}^{-(\mathfrak {Im}\,\zeta _m)\mathfrak {Re}\,k}\), so \(h\rightarrow 0\) as \(|k|\rightarrow 0\) on \({\mathcal {U}}\). To complete the proof, it is thus sufficient to show that \( F-G\in {\mathcal {Q}}\).

Recall from definitions (6.3) and (6.5) that \(F(k)=\det [({\mathbf {I}}-{\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}{\mathbf {S}}_\text {e}(k))-{\mathbf {X}}(k)]\) and \(G(k)=\det [{\mathbf {I}}-{\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}{\mathbf {S}}_\text {e}(k)]\). The entries of the matrix \({\mathbf {X}}(k)\) are all from \({\mathcal {Q}}\), whilst all entries of \({\mathbf {I}}-{\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}{\mathbf {S}}_\text {e}(k)\) are trigonometric polynomials. Now, the expression

can be written as a sum of determinants of matrices formed from combinations of rows of \({\mathbf {I}}-{\mathbf {S}}_\text {v}{\mathbf {S}}_\text {e}(k)\) and \({\mathbf {X}}(k)\). The only one of these determinants which does not involve rows of \({\mathbf {X}}(k)\) is equal to G(k) itself; the other determinants are thus all elements of \({\mathcal {Q}}\). Then \(F-G\in {\mathcal {Q}}\) as required. \(\square \)

6.3 Multiplicity of Eigenvalues

Given an eigenvalue \(\lambda =k^{2n}\) of  , we refer to the dimension of the \(\lambda \) eigenspace as the geometric multiplicity of \(\lambda \) and the order of k as a root of the secular function as the algebraic multiplicity of \(\lambda \).Footnote 4 As usual, assume that

, we refer to the dimension of the \(\lambda \) eigenspace as the geometric multiplicity of \(\lambda \) and the order of k as a root of the secular function as the algebraic multiplicity of \(\lambda \).Footnote 4 As usual, assume that  satisfies Assumption 5.3. Now, Lemma 6.1 implies that the algebraic multiplicity is equal to the order of k as a root of F, provided that \(k>\gamma _\theta \). Ideally, one would prove that the latter equals the geometric multiplicity of the eigenvalue. Of course, one can easily show that geometric multiplicity is at most equal to algebraic multiplicity:

satisfies Assumption 5.3. Now, Lemma 6.1 implies that the algebraic multiplicity is equal to the order of k as a root of F, provided that \(k>\gamma _\theta \). Ideally, one would prove that the latter equals the geometric multiplicity of the eigenvalue. Of course, one can easily show that geometric multiplicity is at most equal to algebraic multiplicity:

Lemma 6.3

Let  be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\). Under Assumptions 3.4 and 5.3, the geometric multiplicity of any positive eigenvalue \(\lambda >0\) of

be an n-Laplacian in \(L_2(\Gamma )\). Under Assumptions 3.4 and 5.3, the geometric multiplicity of any positive eigenvalue \(\lambda >0\) of  is at most equal to its algebraic multiplicity.

is at most equal to its algebraic multiplicity.

Proof

Let \(\lambda =k_0^{2n}\) be an eigenvalue of  with geometric multiplicity M. The matrix \({\mathbb {I}}-{\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}{\mathbb {T}}_\text {e}(k_0)\) has rank \(n-M\); in other words, any set of \(n-M+1\) of its columns is linearly dependent. Now, for each \(j=1,\dots ,M-1\), the jth derivative of (6.1),

with geometric multiplicity M. The matrix \({\mathbb {I}}-{\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}{\mathbb {T}}_\text {e}(k_0)\) has rank \(n-M\); in other words, any set of \(n-M+1\) of its columns is linearly dependent. Now, for each \(j=1,\dots ,M-1\), the jth derivative of (6.1),

can be written as a sum of determinants of matrices each of which contains at least \(n-j\) columns of the matrix \({\mathbb {I}}-{\mathbb {T}}_\text {v}{\mathbb {T}}_\text {e}(k)\). Thus, at \(k=k_0\), the jth derivative of F vanishes. Hence, \(k_0\) is a zero of \(\chi \) of order at least M. \(\square \)

It would be convenient to be able to see equality of these multiplicities in the same way as one can for Laplacians (see, for example, Theorem 3.7.1, [8]) or, more usefully for us, the Dirac operator  :

:

Lemma 6.4

The geometric multiplicity of any positive eigenvalue \(k>0\) of the Dirac operator  , defined by (6.6), is equal to its algebraic multiplicity as a root of the secular function \(\det [{\mathbf {I}}-{\mathbf {U}}{\mathbf {S}}_e (k)]\).

, defined by (6.6), is equal to its algebraic multiplicity as a root of the secular function \(\det [{\mathbf {I}}-{\mathbf {U}}{\mathbf {S}}_e (k)]\).

Proof

The proof is identical to the proof of Theorem 3.7.1 in [8]: the eigenvalues \(\mathrm {e}^{\mathrm {i}\theta _j(k)}\) of the matrix \({\mathbf {U}}{\mathbf {S}}_\text {e}(k)\) satisfy \(\det [{\mathbf {I}}-{\mathbf {U}}{\mathbf {S}}_\text {e}(k)]= \prod _{j=1}^d(1-\mathrm {e}^{\mathrm {i}\theta _j(k)})\). By unitarity of \({\mathbf {U}}\), one has \(\frac{\mathrm {d}\theta _j}{\mathrm {d}k}>0\) for every j according to Theorem 3.7.2 in [8]. Thus, the (algebraic) multiplicity of k as a root of \(\det [{\mathbf {I}}-{\mathbf {U}}{\mathbf {S}}_e (k)]\) is equal to the multiplicity of 1 as an eigenvalue of the matrix \({\mathbf {U}}{\mathbf {S}}_e(k)\). It is clear from the definition of the operator that the latter is equal to the (geometric) multiplicity of k as an eigenvalue of  . \(\square \)

. \(\square \)

Unfortunately, when \(n\ge 2\), the exponential components of \({\mathbb {T}}_\text {e}(k)\) impede this approach for n-Laplacians. To prove equality of the two notions of multiplicity for eigenvalues of  , at least for sufficiently large eigenvalues, we will again appeal to the theory of almost periodic functions. The complete proof is found in Theorem 6.3.

, at least for sufficiently large eigenvalues, we will again appeal to the theory of almost periodic functions. The complete proof is found in Theorem 6.3.

7 Almost Periodic Functions and Holomorphic Perturbations

We turn our attention now to the theory of almost periodic functions. For a detailed study of these functions, the reader is referred to [10] or Chapter VI in [50]. Before we recall the definition, we introduce the following conventions that are used throughout this section.

A (horizontal) strip is an open set \({\mathcal {S}}\subset {\mathbb {C}}\) of the form