Abstract

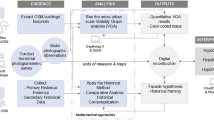

In the Bramante’s church of Santa Maria Presso San Satiro, a successful integration between architecture and perspective solves the lack of space for the choir building. The surprising effectiveness of the trick that simulates a choir depth comparable to the transept’s length was a “Mirabile artificio”. Just because of the perceived room, historians tied the church to the debate on the central plan and the development of the building of San Pietro in Rome. The present research elaborated an accurate laser scanner architectural survey and subsequent digital modeling to find perspective variables and verify the original design concept. 3D reconstruction of virtual architecture unveils the point of view of the simulation, confirming the common hypothesis about architecture, despite the different point of view. The digital model highlights metric evidence, which leads to a vantage point that collimates fake choir in nave perspective, identifying the “Mirabile artificio” as a case of anamorphosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction, the Church

The paper shows the goal of a yearlong research about the Renaissance church of “Santa Maria presso San Satiro” in Milan, one of Donato Bramante’s most famous works due to the wonderful solution of its fake choir, where a shallow solid perspective simulates the same depth of the transept.

Bramante was the architect on a documentary basis, but despite several studies on the church, there are no documents or drawings describing how he managed to construct the fake choir to simulate a Latin cross with a tau plan. He, who was already known as “il Prospettivo”, established his fame with this fake room, which paved the path for architectural perspective and scenography by transforming perspective from a rational representation of space into a perceptual illusion.

The research succeeds a wider-ranging research project on Architectural Perspective, funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Scientific Research in 2012, those output unveiled some particularities that suggested further studies on the church with to understand the real reason of the appellation “Mirabile Artificio” (admirable artifice) that the church earned whit the esteem of contemporary people. It is the first exceptional example of the use of a deceptive perspective application, revealing the further integration of perspective and architecture during the XVI and XVIII centuries.

Does the appellation “Mirabile Artificio” only stem from the artifice that solves the lack of space? None of previous study explained it.

Some argumentation about the church and the survey’s evidences are important for the comprehension of second research outcome.

The church is a landmark in the architectural debate on the San Pietro edifice in Rome, also with reference to the Renaissance development of the central plan. This is the common opinion among historians, despite the fact that the nave is longer than the transept. Both references to San Pietro and the central plant stem from the artifice that offers the perspective solution and solves the constraints that prevented the construction of a long masonry choir. This perspective application with an illusory intent was new and totally extraneous to the concept of mathematical measurement of space that featured in the first Renaissance, and it opened the way to the “quadrature” flowering in interior decoration and to further Baroque applications in scenography (Salvatore and Baglioni 2017).

The interior offers a cross plan, and the church is considered a prelude to the central plan, simulating a Greek cross. This was the case with several other Renaissance churches dedicated to Santa Maria, the majority of which have a central plan. The building is linked to a prodigious event (Lotz 1955). In 1442, Maria’s portrait in the chapel close to the small San Satiro shrine was erected before 879 by Ansperto, Archbishop of Milan (Buratti 1992) was stabbed, after which it bled, drewing many pilgrims. Duke Ludovico Sforza financed a new, bigger church to host the holy image on the altar (Marrucci 1987), with the left arm of the transept in front of the shrine entrance. The engagement resulted in a basilica between the shrine and Via Torino. A narrow street at the back prevented from building a deep choir beyond the transept, so Bramante created a fake choir with a perspective in wood and plaster, which gave the illusion of the space he was unable to build (Fig. 1).

The frontal view of the choir recalls Masaccio's Trinity with a real scale application of Donatello's “relief perspective”, achieving a realistic effect by visualizing a different space from the built one. This solution was innovative in the strong relationship with the architecture. Perspective was no longer a mere representation of a metric space. It became a device to change the space introducing to Architectural Perspective (Rossi 2016).

Several scholars studied the fake choir and its illusory effect, searching for the station point corresponding to the illusion of the same depth of the transept’s aisles, but they suggested different Station Point distances, founding the same hypothesis on different lengths. (Fig. 2). Bruschi (1969: 745–750), and later Camerota (2006: 247–248), identified the station point at a 2.6 m height and the observer’s distance in golden ratio with the width of the picture plane, defined by the nave width. The comparison with the real building, demonstrates that they based on an arbitrary graphical reconstruction of the choir geometry, as it cannot be superimposed even on the existing surveys by Maspero (1938) and Cassina (1940/1962), which are rather correct in the perspective point, and are relatively consistent with the laser scanner survey we carried out in 2013.

Bruschi’s work on Bramante is seminal, but he probably worked without a measured survey, as most historians did fifty years ago. In Italy, during the XIX and early XX centuries, many monument elevations were based on Alinari’s photos.Footnote 1 E. Robbiani (1980: 264) and R. Sinisgalli (2001) set the station point at the height of 2.10 m and the observer on the edge of the first bay at about 13.90 m from the picture plane. Here again, the published drawing cannot be superimposed onto the existing surveys (Fig. 2).

A difference in the point of view’s height is surprising, but it can be explained by the lack of a measured survey. The central vanishing point lies on the concurrence point of the vault’s straight lines simulating the depth ribs of the fake choir. This point is easy to find on vertical plane photos and it is quite correct in both Maspero and Cassina’s surveys, which overlap. Their focus was the concept, not the application. They probably based the choir elevation on photos from higher station points, which would raise the coffers’ point of convergence in the fake vault, fixing the central point in the tabernacle, suggesting an “ideologic” reconstruction of the perspective, apparently vitiated by a symbolic prejudice. These station points are higher than the solution described in Renaissance treatises; Alberti fits at 3 Florentine arms, corresponding to about 1.75 m, comparable to the height of the eye of a man of good build.

Most architectural historians underline the role of the church in the development of the central plan and the debate on San Pietro’s building in Rome (Bruschi 1969). Moreover, when considering the perceived rather than the built space, it is not comparable to a Greek cross because the nave has 5 bays while the transept wings and fake choir have just 3. In any case, this ideal layout bears some resemblance to Bramante’s San Pietro. He designed a central plan imprinted with all the following architectural goals for the new church, which had to be the most remarkable building in the Roman Catholic Church. Bramante’s concept recalls San Satiro, becoming the template for subsequent projects, confirms the Milanese church’s role in the debate over San Pietro and the development of the central plan, despite its tau plan (Fig. 3).

The Research: Survey and Digital Simulation

No other study followed the geomatic survey published by Adele Buratti in 1992, which focused more on the church structure and on its façade than on the structure of the choir’s "relief perspective," which was only briefly represented in the section. Prior to important research on the Architectural Perspective in Italy that granted the opportunity of a laser scanner survey (Buratti et al. 2018), any geometric analysis of the perspective looked at the relationship between the fake choir and the actual architecture in order to understand the real significance of the Bramante experiment.

The survey provided a thorough 3D model of the church’s virtual space, accepting the premise that the choir is as long as the transept wing. By working on the virtual model, we fixed the station point in a conclusive position on real architecture, confirming the accepted theory. Experimental application on the digital model confirms theories concerning Bramante’s objectives (Fig. 4).

The survey highlighted some irregularities in the architecture as well as in the choir, already discussed in previous publications (Buratti et al. 2018, 2019).

It is worth restating that the digital survey illustrates Bramante’s dexterity in concealing several architectural constraints. The building’s layout is regular, but it exhibits certain symmetry anomalies, emphasizing Bramante’s skills in applying illusion devices to hide the constraints resulting from pre-existent structures, such as:

-

The shift between the nave and choir axis

-

The cornice’s overhang to hide the circular dome over a rectangular transept,

-

The asymmetry of the fake choir and its shift with the nave.

-

The different width of the nave and transept (1 Milan foot = 0.594936481 cm) precluded the direct use of the transept wing, but this was circumvented by using 3 nave bays instead of the transept.

-

Due to the asymmetry in the fake choir and the axes shift, the positions of the Station Point (SP) and P3, which are on the same straight-line coinciding with the longitudinal axis, remain uncertain (Fig. 5)

The mesh of the nave’s point clouds facilitated the reconstruction of the virtual choir, confirming the hypothesis of a central plan with a transept as long as the nave and choir. Little adaptation to the digital model was required due to their different brightnesses. The virtual choir model then allowed collimation between points in the illusory space and the “real” perspective choir to search for the theoretical PV in the intersection between the collimation lines and the church axis on the horizontal plane. While the determination of the horizon was immediate, the reverse perspective collimation in SP showed a shift between the right and left half because of small asymmetries in the architecture and collimation uncertainty. Therefore, the station point resulted in an interpolation of possible points inside a wider area in which the station point is not the center of gravity. It is the axis point that better solves the design problem. The reference to a modular grid based on the historical system was the only available tool to confirm the original design point.

Following these premises, and assuming the depth of the theoretical choir is equal to the length of the transept arm, the reconstruction sets the station point at 39 Milanese feet before the choir’s frontal plane, which is supposed to be the picture plane π. It falls in the “central” bay of a theoretical Greek cross plan. The depth of the fake choir in Bramante’s “perspective machine” is 3 Milanese feet. The station point is 4 feet from the original floor level, corresponding to 3 Florentine arms, as Alberti recommends. This lower horizon confirms that previous scholars did not base their reverse perspective on architectural surveys.

While the height, referred to in the purported original floor plan,Footnote 2 is expressed by a significant number, the distance is not. Otherwise, the sum of the two distances is 42 feet, which is equivalent to 7 Trabucchi (1 Trabucco = 6 feet). This suggests that Bramante put his operative picture plane on the back wall of the choir (Fig. 6).

The overlapping of the longitudinal section with a grid of Milanese feet validates the goal through numerical evidence. It confirms the theory that the fake choir repeats the depth of the transept arm since the perspective variables are bound to each other, and the position of the centre depends on the presumed depth. At the same time, the search for the station point and its verification highlights certain anomalies, thereby initiating a new phase of research.

The modelling of the fake and virtual choirs identifies the position of the station point with sufficient precision, in accordance with the architectural articulation indicated by historians’ critics. The SP lies just inside the boundary of a theoretical central plan, where the perspective may range from the dome to the lantern, as Robbiani pointed out. This may confirm that Bramante wanted a cross plan with three bays, but in the nave which has five. This is not a central plan.

The survey results revealed certain anomalies, thus raising new questions which sparked renewed interest in the fake choir and further study on the digital model, with the goal of clarifying what the “Mirabile Artificio” truly was, which is actually the persistence of the illusion along the axis. The simulation on the virtual model shows that the illusion survives along the church axis up to the station point. It is no longer noticeable because a double entrance door has prevented entry into the church on the perspective axis for decades. The following development sheds new light on the role of Bramante’s masterpiece in the development of the architectural perspective and its relationship to the debate over the central plan and the building of San Pietro in Rome.

The “Mirabile Artificio”

The illusion remains effective as one moves into the nave up to the fake choir’s SP. Some interventions in the church, particularly the contemporary wooden inner door and the higher floor level, obstruct the SP’s visual observation in the nave. The virtual path along the axis in the digital model prevents the effects of transformation. As Robbiani writes, shortly after the SP, in the middle of the central bay, one can see the dome up to the lantern. Assuming that the “Mirabile Artificio” is the dynamic effectiveness of the illusion along the nave, the range is only verifiable through digital simulation because of the modern entrance door that prevents axial entrance. The perspective effect is quite convincing in the 3D simulation all along the nave to the choir’s station point, as well as when moving left or right up to roughly 5 Milanese feet, corresponding to half of the nave width. Left and right are not identical because of the church’s slight asymmetry, which enlarges the perspective range in the overall perception. However, the persistence along the length suggests a kind of dynamic station point along the axis, up to the SP of the choir, where the illusion vanishes.

The projective pattern of the “Mirabile Artificio” originated from a simple 3D scheme. The study of San Satiro’s survey shows how Bramante’s innovative solution originated from the dynamic transposition of the scheme described by Leon Battista Alberti in De Pictura (1435). It corresponds to the demonstration by Piero della Francesca of the XIII theorem in De Prospectiva Pingendi (Nicco Fasola 1984; Migliari et al. 2016; Casale 2018; Cocchiarella 2021), written between 1474 and 1482, when Bramante built the church (Fig. 7). The reference to Alberti and Piero's pattern raises new questions about the “Mirabile Artificio”. In light of survey evidence, attributing it to the simple choir simulation is reductive. Rather, it seems to be a reference to the "dynamic" persistence of the virtual choir along the nave.

Knowing the position of SP does not solve any questions concerning the choir’s realization, nor does it explain the illusion’s effectiveness all along the nave, where you can live in the 3D simulation, because it is the point where it begins to fail. In fact, the problem is not the choir’s perspective, but the collimation with the nave’s perspective. That happens if and when all the depth lines converge on a single point, which means that the fake choir and the nave’s depth lines collimate (Fig. 8). Furthermore, the station point SP is far enough ahead to see the nave inside the visual cone.

The solution lies in the vantage point VP, which collimates the choir and the nave perspective into a sole perspective point P on the picture plane. This does not explain the evidence resulting from the virtual simulation, which suggests that it is not a vantage point, but a vantage line. The real problem is explaining why the collimation does not fail in the walk between the VP and SP. The longitudinal section demonstrates that Bramante’s “perspective machine” refers to the same graphic scheme and demonstrates his deft mastery of the projective-perceptive process, which fixes all perspective variables at key points in the church design. The church’s particular proportions and measurements demonstrate that the whole project was the result of a rigorous geometric control of the fake choir perspective, which is the keystone of research goals. On the surveyed longitudinal section, the Alberti and Piero’s perspective pattern fixes the vantage point VP in a particular position. By extending the line between the fake choir front’s springing point A on the plane π, its translation A2 on π2 intersects the axis in VP, just on the vertical of the cornice of the internal façade wall.

The vantage point is not just on the door, but it is on the first step inside the church, and it is exactly 42 feet from the inner plane of cross vault π2, which is symmetrical to π0 with regard to the transept axis. This peculiarity prompts us to consider what happens at this point, searching for an explanation for such a precise coincidence that does not appear to be fortuitous. In the VP, the nave perspective collimates with the view of the fake choir (Fig. 9).

Therefore, the “Mirabile Artificio” is not the static perception of a dilated space, but the dynamic management of the visual perception that creates a virtual space from VP to SP, beyond which the illusion disappears. It is the effect of the picture plane translation, which does not change the perspective, as everybody knows.

The 3D transposition explains what happens in Bramante’s “perspective machine.” This new pattern shows that SP and VP are the two extremes between which the station point may move, maintaining the right perspective. VP matches the translation of the picture plane from the choir to the nave’s main arches. The station point (SP) loses its importance as the relief-perspective vantage point, becoming the end point of the perspective artifice that appears when walking from the entrance to the altar in the first three bays of the nave from the VP to the SP (Fig. 10).

The pattern translates Alberti and Piero’s scheme that rules the solid perspective construction, moving the picture plane within the cross-vault depth, whose pillars have capitals the same height as the springing line of the fake choir. Simply put, the church’s “perspective machine” adapts the pattern to the church. Recourse to a modular space explains the operation, verifying the effect on a set of cubes: in (1) it is ½ l and l, respectively, and in (2) it is l and 2 l. The first cube’s perspectives on the first and second “face” are equal, and they translate by l. That is hardly a matter of chance.

Taking into account π1 on the back wall and π2 on the first side of the transept, the vantage point VP is just on entering the church, where the perspective encompasses three bays of the nave. The distance P depends on the translation of the picture plane and collimation of two perspectives admits a single solution depending on the translation distance, as shown by a set of cubes (Fig. 10). One of these (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H) encloses the choir. The latter is put into perspective from the station point (P′) at zero height and a distance equal to half the cube side (1/2 l) on the faces E, F, G, and H (square). The cube perspective is reduced in the points A′, B′, C′, and D′. If the station point is moved to P at a distance equal to 3/2 l from P and the frame on the second face of the second cube I, L, M, and N, and the two cubes (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H and E, F, G, H, I, L, M, and N) are placed in perspective at the points E′, F′, A″, B″, G′, H′, C″, D″, I, L, M, and N, they are ½ l and l in a) and l and 2 l in b), respectively. Only in the case of square bays does the second length double the first distance. The ratio changes with rectangular bays, adapting to different proportions.

The first cube (right) contains the image of the solid perspective on the picture plane, the second cube adds the perspective of another, as well as the central nave with the choir's solid perspective, aligning them. In fact, San Satiro’s longitudinal section illustrates the application of the pattern using parallelepipeds rather than cubes.

If the picture plane moves backwards with the station point by a distance equal to the side of the cube, the two perspectives overlap, and the illusion remains valid. Therefore, the station point (SP) would not be a privileged station point. It is merely the dividing line beyond which correspondence between reality and fiction dissolves. This pattern explains how Bramante implemented his concept through a square grid that fixed the elements of the scenic artifice, which was admirable because of its dynamism.

As Piero della Francesca wrote (Casale 2018; Cocchiarella 2021), the artifice solution is simply this double perspective pattern drawn in plan and section.

SP lies at a distance of 39 Mf if picture plane π1 lies on the back face of the transept. The fake choir P3’s coffer vault convergence point is approximately 8 Mf beyond π1, outside the church, while the back wall of the apse is 3 Mf away. Assuming the picture plane is π2, on the back wall, it divides the distance between the choir’s advanced and back plane in an approximate golden ratio (8 = 3 + 5 Mf). P3 falls into the street, leaving about 6 Mf (about 2.60 m) from the building on the other side of Via del Falcone, suggesting that the design and construction picture plane was π1 on the back wall, which is 42 Mf from the SP, that is, the same distance for the vantage point VP from π2 (Fig. 11).

The builders probably traced the wooden frame of the choir stretching wires between the two picture planes from P3, directly on the worksite prior to the construction of the back wall, or on a 1:1 scale model aside, without obstructing passage in the street. The distance between SP and P3 is 42 Mf, as is that between the SP and the entrance. The longitudinal section shows proportional relationships in the double perspective pattern: the significant measurements are in a series of numbers with the golden ratio but not the Fibonacci one (Fig. 11).

As highlighted by other scholars (Proietti and Gepshtein 2021), a double perspective is an anamorphosis. Bramante’s stratagem of aligning the solid perspective from the SP with the nave perspective from the vantage point VP is perhaps the first anamorphic experiment. In San Satiro, the illusion is effective from the entrance to the station point of the simulated choir. The key is in the perspective pattern that collimates the nave and the choir in a double perspective.

This pattern applies two coincident projection directions to two parallel picture planes; this combination does not distort but enhances the perspective.

The special case of two projections on parallel planes results in a dynamic perception without any strain along the distance between the VP (vantage point) and the SP (the fake choir’s station point). The distance between the SP and the picture plane is equal to the transept length, suggesting that Bramante could have drafted the fake choir frame on the real structure of the transept, aligning the vault from a station point on the shrine door. He applied Alberti’s perspective veil, anticipating Durer’s perspective machine (1538) with a real-scale application (Fig. 12).

Conclusion

Bramante's mastery springs forth in the elegance of the relationship between the real architecture and the perspective apparatus, demonstrating that once the architect acquired the instruments for the measurement of space in perspective, he exploited its representative potential, applying its illusory effect to interior decoration as a spatial integration of the architecture itself.

The fake choir of Santa Maria presso San Satiro in Milan is known as one of the most remarkable monuments in the city. It is a perspective apparatus capable of simulating a depth similar to the length of the transept arms in the thickness of a niche. It represents one of the most notable examples of the perceptive effectiveness of perspective, which was lost because of the floor elevation in the mid-sixteenth century and the construction of a wooden entrance door that altered visitors' access.

The artifact has astounded visitors since its construction. The awe inspired by the ingenious solution to the lack of space, which obviated the need for a real choir, gained the admiration of contemporaries, who named it the "Mirabile Artificio". It sparked interest in the design hypothesis underlying the perspective construction, and the choir and its perspective are not novel subjects of study. Although there are some references in the specific literature to hypotheses about the station point of relief perspective, nobody refers to the vantage point that collimates the nave and choir as the true solution to the illusion of effectiveness along the nave, up to the station point.

It was the first experimental case of perspective as an illusory artifact to change the built architecture and the perceived space within it, which paved the way for other applications in the following two centuries. They flourished in Italy, particularly in the fields of theatre scenography and quadrature. This latter is just the decoration of rooms with painted perspectives, which is characteristic of Italian Baroque (Rossi and Russo 2021).

The geometric pattern reveals a space concept that is open to scenic perception and perspective representation, confirming the importance of geometry in visual space control. San Satiro's solid perspective became the first model of modern theatrical scenography, which Bramante solved with a simple pattern. In this way, Bramante fixed the empirical basis before Guidobaldo dal Monte's coding (1600) and subsequent application in the baroque theatrical scenography (Baglioni and Salvatore 2017), according to the practical indications of Nicola Sabbatini (1638). At the end of the fifteenth century, in Milan, perspective became a helpful element for the definition of architectural space. Following Bramante's artifice, quadrature’s application to theatrical scenography was reworked.

Collimating the choir and nave in the real church is not easy, and the station point is too close to the transept to see the nave perspective. The projective problem is simply the collimation of two different perspectives: the illusion of the choir and the view of the nave. The "Mirabile Artificio" is Bramante’s dynamic effectiveness of inner virtual space, which enhances the relationship with the central plan. The station point satisfies the suppositions of architecture scholars, the statements of contemporary treatises, and the perceptive assumptions highlighted in Robbiani's study (Fig. 13).

Explaining the perspective design, the pattern, and the measurement in Milanese feet (Mf) clarifies the original layout and construction management. The reference to a metric grid of Milanese feet identifies the design concept, thus overcoming construction tolerances.

The meaning of “real measurement of space”, initially associated with perspective, was later extended to space and turned into the theatrical game between reality and fiction suggested by Bramante's work. He applied the same method that Alberti describes in the “quadrangolus” to create a virtual space which, like the two Brunelleschi plates, becomes “real” because the image has the same measure of reality. Because of this, the identity between the object and its image makes the measured representation “true.”

Perspective materializes the artifice by which the image interacts with real space, creating a figurative space that extends the room without a solution for continuity. The key is to integrate the station point of the “architectura picta” into real space by using pictorial or plastic devices to hide critical points in the boundary between real and virtual space.

The station point of relief perspective is only the first step to unraveling Bramante’s secret. No document verifies its position more than the architectural survey and the consistency of historical metrology. By aligning the fake choir with the transept’s actual width, the SP would advance in the nave towards the center of the Greek cross's arm, bringing the observer closer to the nave center of the theoretical central space, in a position that is conceptually significant. Once again, the survey leaves no room for doubt. The longitudinal section highlights a recurrence in the distance between significant perspective elements and proportions that underlines the correctness of the 3D model’s perspective reconstruction. Small irregularities and asymmetries widen the simulated perception of the main part of the nave. The digital check on the architectural survey verifies the theoretical design hypothesis concerning the simulation of an ideal model, which is coherent with the architecture despite the difference in the plan. Geometry confirms the consolidated historians’ thesis that the church is a reference to the central plan development in the late 1400 s. Bramante created a virtual view of a cross plan with transept arms, a choir, and a nave of the same length by placing the vantage point in the entrance of a nave that is longer than the other arms. Entering the church, the visual cone from the vantage point of the anamophosis shows the simulated perspective of a Greek cross layout (Fig. 14).

Notes

Alinari has been working for important international institutions since 1852. Alinari is the longest established company in the field of art and monument photography and used to edit architecture photos during the printing process in order to eliminate the vanishing point on the z axis.

During restorations in the twentieth century, a portion of a brick tile floor was found about 20 cm under the current floor level.

References

Baglioni, Leonardo and Salvatore, Marta. 2017. Principi proiettivi alla base della prospettiva solida nella scenografia di Guidobaldo dal Monte. In ed. A.A. V.V. Territori e frontiere della rappresentazione, 267–276. Roma: Gangemi.

Bruschi, Arnaldo. 1969. Bramante architetto. Roma-Bari: Laterza.

Buratti Mazzotta, Adele (edited by). 1992. Insula Ansperti: il complesso monumentale di S. Satiro. Milano: Banca Agricola Milanese.

Buratti Giorgio, Mele Giampiero, and Rossi Michela. 2018. The Perspective as immaterial Building. The fake Choir of Santa Maria by San Satiro. In Salerno R ed., Drawing as (in)tangible Representation, 215–224. Rome: Gangemi.

Buratti Giorgio, Mele Giampiero, and Rossi Michela. 2019. Perspective Trials in the Manipulation of Space. The Bramante’s Fake Choir of Santa Maria presso San Satiro in Milan. Diségno. N. 4/2019, 41–52.

Camerota, Filippo. 2006. La prospettiva del Rinascimento: arte, architettura, scienza. Milano: Electa.

Casale, Andrea. 2018. Forme della percezione. Dal pensiero all’immagine, p. 156–157. Roma – Milano: Franco Angeli.

Cocchiarella, Luigi. 2021. Orthographic Anamnesis on Piero della Francesca’s Perspectival Treatise. In Nexus 20/21 Architecture and Mathematics Conference Book, 7–12. Turin: Kim Williams Books.

Dal Monte, Guidobaldo. 1600. Perspectivae libri sex. Pesaro: Girolamo Concordia.

Lotz, Wolfgang. 1955. Die ovalen Kirchenräume des Cinquecento. In Römisches Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte, vol. 7, 7–99. Wien: Wasmuth Schroll.

Marrucci, Rosa Auletta ed. 1987. La prospettiva bramantesca di Santa Maria presso San Satiro: storia, restauri e intervento conservativo. Milano: Banca Agricola Milanese. Catalog of the Exibition in Milan in 1987.

Migliari, Riccardo et al. 2016. Piero della Francesca De prospectiva pingendi. Roma: Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato.

Nicco Fasola, G. ed. 1984. Piero della Francesca. De Prospectiva Pingendi, 75. Edizione critica. Firenze: Le Lettere.

Proietti, Tiziana and Gepshtein, Stefan. 2021. Psychophysics of Architectural Proportion in Three Dimensions. In Nexus 20/21 Architecture and Mathematics Conference Book, 43–48. Turin: Kim Williams Books.

Robbiani, Eros. 1980. La verifica costruttiva del finto coro di Santa Maria presso San Satiro a Milano. In ed. Marisa Dalai Emiliani ed. La prospettiva rinascimentale: codificazioni e trasgressioni, Vol I, 215–231. Firenze: Centro Di.

Rossi, Michela. 2016. Architectural Perspective between Image and Building. Nexus Network Journal. Vol. 18/3, 577–583. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Rossi, Michela and Michele Russo ed. 2021. L’eredità di Bramante tra spazio virtuale e protodesign. Milano-Roma: Franco Angeli open access.

Sabbatini, Nicola. 1638. Pratica di fabbricar macchine e scene né teatri. Ravenna: Pietro de Paoli e Gio Battista Giovannelli.

Sinisgalli, Rocco. 2001. Verso una storia organica della prospettiva. Roma: Edizioni Kappa.

Acknowledgements

All authors worked together on the architectural survey and throughout the research development process, discussing survey evidence and expounding further considerations. Michela Rossi coordinated the work, Giampiero Mele dealt with historical references in treatises and practice, and Giorgio Buratti developed the point cloud in the virtual model for digital verifications. With reference to the final discussion in this article, Michela Rossi wrote the introduction, conclusion, and part of Sect. 3, Giorgio Buratti wrote Sect. 2 and part of 3, while Giampiero Mele wrote the perspective-machine description in Sect. 3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Buratti, G., Mele, G. & Rossi, M. The Masterly Perspective and Design of Bramante’s “Mirabile Artificio” in Milan. Nexus Netw J 24, 545–565 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00004-022-00604-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00004-022-00604-0