Abstract

The post-mortem inspection of domestic pigs within the European Union was revised in 2014, primarily to include visual meat inspection of each carcase and offal. Palpations and incisions were removed from routine meat inspection procedures, as they are mostly used to detect pathological lesions caused by organisms irrelevant for public health, and instead can cause cross-contamination of carcases with foodborne pathogens. However, examination of all external surfaces of the carcase and organs, declaration of patho-physiological lesions as unfit for human consumption, and possibility for minimal handling of carcases and offals were held in place. In addition, the European Food Safety Authority suggested that palpation and incisions should be performed outside the slaughter line, but this was not incorporated in the revised legislation. We surveyed in 2014 the opinions of meat inspectors and veterinarians using an online questionnaire to determine what practical measures are required for the visual meat inspection procedure and when meat inspection staff consider additional palpations and incisions necessary. Based on the survey, turning the carcase and organs or technical arrangements such as mirrors were seen necessary to view all external surfaces. In addition, the pluck set cannot be trimmed on the side line. Local lesions, such as abscesses and lesions in the lymph nodes, signs of systemic infection and lymphoma, were the major lesions requiring additional post-mortem meat inspection procedures. Meat inspection personnel raised concerns on the poor quality of food chain information and export requirements demanding palpations and incisions. The efficient use of visual meat inspection requires legislation to better support the implementation and application of it, changes in the slaughter line layout and a possibility to classify incoming pig batches based on their risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The post-mortem inspection procedure for slaughtered domestic pigs within the European Union was revised in 2014 (EC No 854/2004; EU No 219/2014). According to the revised regulation, post-mortem inspection is visual, with additional incision and palpation in place if possible risk to public health, animal health or animal welfare is indicated. Suspicion of these risks may arise during ante-mortem or post-mortem inspection, or based on epidemiological data or food chain information (FCI). The revision was based on the scientific opinion of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), which stated that the most important public health risks in pork, namely Salmonella spp., Yersinia enterocolitica, Toxoplasma gondii and Trichinella spp., cannot be identified during traditional post-mortem inspection including incisions and palpations (EFSA 2011). In fact, patho-physiological changes, such as abscesses, are an aesthetic meat quality issue that do not affect food safety, and palpations and incisions may spread pathogenic bacteria during meat inspection (EU No 219/2014; EFSA 2011). Therefore, palpations and incisions were omitted from routine meat inspection in the EU (EU No 219/2014). EFSA also recommended that when palpations and incisions are necessary they should be performed outside the slaughter line, but this was not required by the revised Regulation (EC) No 854/2004 (EU No 219/2014; EFSA 2011). According to Regulation (EC) No 854/2004, an official veterinarian is required to view all external surfaces during post-mortem inspection. In addition, the official veterinarian must declare meat unfit for human consumption if it indicates patho-physiological changes.

In 2014, an online questionnaire was prepared for meat inspection veterinarians and meat inspectors, to investigate whether performing visual meat inspection is possible in practice in Finnish slaughterhouses, as regulated in Regulation (EC) No 854/2004 and recommended by EFSA (2011). In this legislation derived study, our aim was to investigate, whether it is technically possible to (1) visually inspect all parts of a carcase, pluck set and intestines without handling the inspected part (“hands off” inspection) and (2) further reduce cross-contamination by frequent hand washing and by trimming pluck sets on a side line. In addition, (3) meat inspection staff and veterinary pathologists were asked what types of abnormalities, possible diagnoses or pathologies they consider to require additional palpations and incisions listed in the Commission Regulation (EU) No 219/2014.

2 Materials and methods

An electronic questionnaire (Table 1) was prepared using Webropol (Helsinki, Finland) survey and analysis software. The questionnaire was sent to official veterinarians and official auxiliaries in all slaughterhouses supervised by the Finnish Food Safety Authority Evira (Finnish Food Authority 1.1.2019 onwards) along with regional directors (experienced meat inspection veterinarians and superiors to meat inspection veterinarians and meat inspectors in slaughterhouses) and senior inspectors in the Meat Inspection Unit of Evira responsible for the management and guidance of meat inspection personnel. The questionnaire was sent in spring 2014. The list of full time meat inspection veterinarians (n = 52) and official auxiliaries (n = 48) was compiled from email lists owned by Evira. In addition, a list of production animal pathologists (n = 13) working for Evira and at the University of Helsinki, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine was compiled from the contact lists of both organizations and by verifying the accuracy of the list from one pathologist working at both organizations. The questionnaire was sent as an email link. After the original message, a reminder email was sent on three occasions to recipients who had not answered the questionnaire. The reason and changes made to the meat inspection procedure were shortly described in the forewords of the questionnaire.

The questionnaire comprised of four parts:

- 1.

Respondent background

- 2.

Visual meat inspection in practice

- 3.

Incisions and palpations according to revised Regulation (EU) No 854/2004 and

- 4.

Other comments (Table 1).

Questions 1–13 were treated as bivariate questions and were also modified from simple Yes/No responses to a 3-level scale: “Yes”, “Handling or technical arrangements needed at the very least” and “No” based on the open comments. Questions 14–17 were treated as a 3-level scale (Figs. 2 and 3) and also reduced to a simple bivariate Yes/No. The concerns expressed by veterinarians and meat inspectors concerning visual meat inspection were gathered from the open comments (questions 1–13) and open questions (17, 27 and 28). The opinions of the required incisions and palpations were collected from the open questions 18–26. The data were processed and figures created using Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). A two-tailed Fisher’s exact test was used to analyse binomial scales and scaled questions, where the answers were divided into positive and negative alternatives, using SPSS statistical software (PASW Statistics 18.0, SPSS IBM, USA). The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to analyse the 3-level scales.

3 Results

Responses were received from 16 veterinarians and 17 meat inspectors (official auxiliaries), with a total response rate of 27%. The responding veterinarians consisted of ten official veterinarians, three out of four regional directors and one out of six senior inspectors from the meat inspection unit of Evira, along with two pathologists from Evira and the University of Helsinki. The response rates for veterinarians and meat inspectors were 21 and 35%, respectively. The official veterinarians and meat inspectors that answered the questionnaire represent five slaughterhouses that together slaughter over 95% of pigs in Finland (Supplementary info 1, Supplementary material).

3.1 Omission of palpations and incisions in routine meat inspection

Over 50% of the veterinarians and meat inspectors considered the visual inspection of the head and throat, mouth, fauces and tongue along with the pleura and peritoneum to be possible without handling. The opinions of veterinarians and meat inspectors did not differ significantly from each other (Table 2 and Fig. 1). In other sites, over 50% of both veterinarians and meat inspectors did not consider “hands off” meat inspection possible. Handling or technical arrangements at the very least were considered necessary (Fig. 1). The opinions of meat inspectors and veterinarians were not significantly different regarding the omission of palpations and incisions except for the umbilical region and the joints of young animals, where 81% of veterinarians and 31% of meat inspectors considered visual inspection to be possible (Table 2 and Fig. 1). In the open comments and questions, the meat inspection personnel expressed various concerns of the visual meat inspections, particularly on the lack of visibility to the external surfaces, in cases were handling of the inspected parts is not allowed and also within inspected parts, when routine incisions are omitted (Table 3).

Possibility of performing visual inspection in the slaughter line without handling the carcase, pluck set or intestines (questions 1–13) according to the opinions of veterinarians (Vet) and meat inspectors (MI). The columns show the percentage of respondents when their responses were divided into categories “Yes”, “Handling or technical arrangements needed at the very least” and “No”. *The opinions of veterinarians and meat inspectors differed significantly (Mann-Whitney U, p =0.03)

3.2 Reduction of cross-contamination in the slaughter line

When practical aspects of visual meat inspection were inquired, about 67% of meat inspectors considered washing their hands between every carcase and pluck set (comprising the tongue, larynx, oesophagus, trachea, lungs, heart, liver, kidneys) possible. Veterinarians provided a similar estimate, as 55 and 64% considered hand washing after every carcase and every pluck set possible, respectively (Table 4; Fig. 2). The majority of both veterinarians (73%) and meat inspectors (75%) considered the trimming of pluck sets outside the slaughter line impossible (Table 4; Fig. 3). The open comments showed that trimming the abnormal offal outside the slaughter line was considered problematic, as the side line would become crammed (8/21 respondents) and some farms with low quality pigs would require a lot of trimming (4/21). Slaughterhouse layout is planned for trimming the offal on the line (2/21), whereas carcases requiring a lot of trimming are sent to the side line.

Possibility of washing hands after each carcase or pluck set according to the opinions of veterinarians (Vet) and meat inspectors (MI). The columns show the percentage of respondents when their responses were divided into categories “After each carcase or pluck set”, “After every second carcase or pluck set” “More rarely”. The opinions of veterinarians and meat inspectors did not differ significantly

Possibility to trim pluck sets on a side line or elsewhere out of a slaughter line according to the opinions of veterinarians (Vet) and meat inspectors (MI). The columns show the percentage of respondents when their responses were divided into categories “Yes”, “Yes, but with difficulty” and “No”. The opinions of veterinarians and meat inspectors did not differ significantly

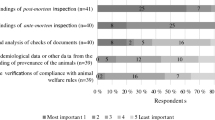

3.3 Additional palpations and incisions

The veterinarians and meat inspectors were asked to describe any local lesions and lesions occurring elsewhere in the carcase or organs indicating a need for additional post-mortem procedures. Mycobacteria was the most commonly mentioned infective agent that required additional palpations and incisions for its preliminary diagnosis (Table 5). The most common local lesions requiring additional post-mortem procedures were abscesses (mentioned 52 times in nine organs or carcase parts) and enlarged or otherwise abnormal lymph nodes (mentioned 26 times in nine organs or carcase parts) (Supplementary table 1, Supplementary material). Other described local lesions were related to the organ in question (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary material). Other commonly mentioned reasons for additional post-mortem procedures were systemic infection and lymphoma (Table 5).

Veterinarians associated systemic infection with all carcase parts and organs. Meat inspectors related systemic infection with the submaxillary lymph nodes, heart, gastric and mesenteric lymph nodes, the spleen and kidneys and the renal lymph nodes. Mycobacteria, Erysipelothrix, Ascaris and cysticerus were mentioned more than once in the open questions (Table 5). Mycobacteria were related to the lymph nodes, lungs, liver, spleen and kidneys.

The spleen and gastric and mesenteric lymph nodes were most noted for possible neoplasms, lymphoma in particular. Other sites mentioned were the lungs and bronchial and mediastinal lymph nodes, submaxillary lymph nodes, the kidneys and renal lymph nodes and the liver and its lymph nodes (Table 5).

4 Discussion

In their responses to the questionnaire, veterinarians and meat inspectors raised several concerns on visual meat inspection. The most prominent issue raised was visibility. The question of visibility was also raised in a previous study performed in the UK (Tongue et al. 2013). According to Regulation (EC) No 854/2004, Annex I, Section I, Chapter II, Part D, point 1, all external surfaces must be viewed in the post-mortem inspection and minimal handling of the carcases and offal or special technical facilities may be required (EC No 854/2004). Throughout the questionnaire, the meat inspection staff noted that this is not possible in most cases without at least handling the carcase and organs or modifying the slaughter line. In addition, a lack of visibility of sites known to harbour patho-physiological changes, particularly the heart, was seen as a problem. The EFSA (2011) stated that microbial agents causing conditions detected at post-mortem pig inspection (e.g. pneumonia, abscesses, endocarditis and pericarditis) are mostly caused by non-zoonotic agents and those that are zoonotic, are mainly occupational, not foodborne risks. Therefore, the reduced visibility does not lead to increased food safety risk, as shown in various studies (Alban et al. 2008; Hill et al. 2013; Pacheco et al. 2013; Tongue et al. 2013; Kruse et al. 2015; Blagojevic et al. 2015; Ghidini et al. 2018). To fulfill the legislative requirement to inspect all external surfaces, different technical solutions may be used, such as mirrors or systems that rotate carcases to allow visibility to all carcase surfaces (Tongue et al. 2013). Different ways to present pluck set and intestines could also be considered. Regulation (EC) No 854/2004 also divides the responsibility of removing patho-physiological changes between the food business operator (FBO) and official control. The operator’s HACCP-based procedures should guarantee to the extent possible that meat does not contain patho-physiological abnormalities or changes (Annex I, Section I, Chapter I, Point 2a) and an official veterinarian has to declare meat unfit for human consumption if it indicates patho-physiological changes (Annex I, Section IV, Chapter V, Point 1p). Most patho-physiological changes are currently seen merely as an aesthetic meat quality issue and irrelevant for food safety (EU No 219/2014; EFSA 2011). In Australia, Pointon et al. (2018) have suggested that the removal of patho-physiological changes could be left as the responsibility of FBOs. EFSA (2011) suggested that with visually undetected heart abnormalities, the removal of the affected hearts could be done during cutting within the abattoir meat quality assurance system. However, EFSA also noted that the responsibility allocation is done by regulators (EFSA 2011). The responsibilities of FBOs and official controls were not changed in the revised Regulation (EC) No 854/2004 nor in Regulation (EC) 2019/627. If patho-physiological changes were to be left outside official controls, the use of meat inspection data to facilitate animal health and welfare should be taken into account. Meat inspection data can provide good information on the health and welfare status of pig farms. It could be used in the surveillance of animal diseases and also to estimate the health, welfare and quality of slaughter pigs (Stärk et al. 2014; Heinonen et al. 2018), although visual meat inspection leads to a loss of data concerning animal health and welfare (Tongue et al. 2013).

4.1 Reduction of cross-contamination

As avoiding cross-contamination is the reason behind the changed meat inspection policy, handling the carcase and organs should be limited to the absolute minimum and hands should be washed if handling is needed. EFSA also recommended that incisions, palpations and subsequent trimming should be done outside the slaughter line. However, neither “hands off” meat inspection (minimal handling of the carcase and offal is allowed in 854/2004 Annex I, Section I, Chapter II, Part D, Point 1) nor performing additional meat inspection procedures outside the slaughter line was incorporated in the revised regulation. According to the meat inspection staff, incisions, palpations and trimming of the pluck set cannot be performed on a side line or elsewhere away from the slaughter line, as the side lines are not large enough and the slaughter lines are designed for on-line inspection and trimming of pluck sets in Finnish slaughterhouses. Tongue et al. (2013) also noted that detention rails in the UK are of insufficient capacity and suggested that further inspections must occur on the slaughter line. Hand washing after each handled carcase and pluck set was mainly considered possible. The Commission implementing regulation (EU 2019/627), applied from 14th December 2019, still requires for the competent authority to check all external surfaces of carcase and offal (article 12 point 3), but no longer specifically mentions that minimal handling is allowed. The site where additional meat inspection procedures should be done, is not specified in the Regulation. However, the Regulation states that “The competent authorities may require the food business operator to provide special technical facilities and sufficient space to check offal” (EU No 2019/627, article 12 point 2). It would seem that Regulation (EU) No 2019/627 takes visual inspection somewhat better into account than the revised Regulation (EC) No 854/2004.

4.2 Food chain information

According to revised EC No 854/2004, the FCI should be used to decide whether a certain batch of pigs needs additional post-mortem procedures. The meat inspection staff suggested in their open answers that, e.g. the use of peat as bedding on farms (a risk for the Mycobacterium avium complex) (Matlova et al. 2005) could be used as an indicator. However, mycobacteria can also be found from other bedding materials besides peat (Pakarinen et al. 2007). Also, previous prevalence of arthritis and Erysipelothrix on a farm was suggested to be used when assessing the need for incisions. FCI quality was also observed to be inadequate for assisting in the decision-making, which has also been noted previously (Luukkanen et al. 2015; Felin et al. 2016). Felin et al. (2016) suggest the use of a prior partial condemnation rate and cough declared in the FCI, as these factors best predicted the partial condemnation rate for a batch. The efficient use of previous meat inspection results in decision-making would require a central database of meat inspection findings that would be used by official veterinarians. The use of FCI to assess the need for additional post-mortem procedures requires further development.

4.3 Export requirements

Official veterinarians noted that visual meat inspection does not fulfil current requirements of the export countries for domestic pigs. Certain exporting EU countries have negotiated the equivalence of visual meat inspection with the meat inspection performed in the third country. E.g. the United States Department of Agriculture Food Safety Inspection Services (USDA FSIS) has provided Denmark with an equivalence for the visual meat inspection of finisher pigs (United States Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service 2016). The Commission is negotiating with USDA for an equivalence for the visual meat inspection of pigs raised within the EU. Such negotiations are also needed with other countries where pork is exported.

4.4 Additional palpations and incisions

According to Regulation (EC) No 854/2004, additional post-mortem inspection procedures should be used, if findings of post-mortem inspection indicate a possible risk to public health, animal health or animal welfare (annex I, section IV, chapter IV, part B, point 2(d)). In our study, signs of local infections of the inspected carcase part or organ, abscesses, mycobacteria, systemic infection and lymphoma were the most common reasons given for additional post-mortem procedures. According to the EFSA report, none of these are considered risks for food safety (EFSA 2011), but rather animal health and welfare issues. Meat inspection data can provide good information on the health and welfare status of pig farms that could be used in the surveillance of animal diseases and also to estimate the health, welfare and quality of slaughter pigs (Stärk et al. 2014; Heinonen et al. 2018), although visual meat inspection leads to some loss of data concerning animal health and welfare (Tongue et al. 2013). Based on the literature, the detection of abscesses, embolic pneumonia, pyemia, fever/septicaemia decreases when using “hands off” visual meat inspection, but the reduction has either not been significant or has been considered not to pose an additional human health risk (Mousing et al. 1997; Tongue et al. 2013; Kruse et al. 2015; Ghidini et al. 2018). In addition, the detection of some local infections can be enhanced in visual meat inspection (Ghidini et al. 2018). In the open questions of our study, lesions in the lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys and their related lymph nodes, along with supramammary lymph nodes, and the umbilical region and joints were often visually clear, and therefore additional post-mortem procedures were not considered necessary to identify the lesion. This is also largely supported by a recent Italian study (Ghidini et al. 2018).

Mycobacteria was the most commonly mentioned microbe in the answers. During 1998–2012 the prevalence of mycobacterium-like lesions in slaughter pigs fluctuated between < 0.1 and 0.85% (Tirkkonen 2017) and Finland is officially free of Mycobacterium bovis (Commission Decision 2003/467/EC). Recently, Mycobacterium caprae has emerged in various European countries (Cvetnic et al. 2006; Rodríguez et al. 2011; Amato et al. 2017) and should also be considered. As passive surveillance, Evira recommended that in cases of pronounced or generalized mycobacterium-like lesions, samples should be sent for further identification of the causative agent (Evira 2015). Blagojevic et al. (2015) estimated that the change from traditional to visual inspection decreases the likelihood to detect the present lesions caused by Mycobacterium spp. in the intestines and related lymph nodes from low to negligible.

Neoplasms, with lymphomas most commonly mentioned by the meat inspection staff in our questionnaire, are rare in slaughter pigs and in Italy, the change from traditional to visual inspection did not decrease the detection of neoplasms (Ghidini et al. 2018).

4.5 Responses by the meat inspection staff

The veterinarians and meat inspectors responded very similarly to each question. The only question where the opinions of the two groups differed significantly was the visual inspection of the umbilical region and joints of young animals, where 81% of veterinarians and 31% of meat inspectors considered visual inspection possible. The most likely reason for this difference in opinions is that piglets are rarely slaughtered in Finland and there is therefore little experience in the inspection of young pigs. The response rate was fairly low. However, the responses represented Finnish pig meat inspection well, since three out of four regional directors and meat inspection staff from pig slaughterhouses slaughtering over 95% of pigs in Finland answered to the questionnaire.

5 Conclusions

The responses to this questionnaire highlighted similar concerns on the practical application of visual meat inspection also noted in other countries. New slaughter lines should facilitate the visual only inspection without touching the carcase and offal, and have a side line large enough for all additional palpations, incisions and trimming of the lesions. Furthermore, problems related to the quality of food chain information must be solved. Negotiations are needed concerning the requirements of the export countries for pig meat inspection. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/627 clarifies some of the practical questions in implementation of visual meat inspection: In the Regulation, the possibility for minimal handling of the carcase and offal is omitted and the possibility to require special technical facilities and sufficient space to check the offal is added.

References

Alban L, Vilstrup C, Steenberg B, et al (2008) Assessment of risk for humans associated with Supply Chain Meat Inspection—The Danish Way. Danish Agriculture and Food Council. 55 pp. https://lf.dk/aktuelt/publikationer/svinekod. Accessed 5 Dec 2019

Amato B, Capucchio TM, Biasibetti E et al (2017) Pathology and genetic findings in a rare case of Mycobacterium caprae infection in a sow. Vet Microbiol 205:71–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.05.010

Blagojevic B, Dadios N, Reinmann K et al (2015) Green offal inspection of cattle, small ruminants and pigs in the United Kingdom: impact assessment of changes in the inspection protocol on likelihood of detection of selected hazards. Res Vet Sci 100:31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2015.03.032

Commission Decision 2003/467/EC Commission Decision of 23 June 2003 establishing the official tuberculosis, brucellosis, and enzootic-bovine-leukosis-free status of certain Member States and regions of Member States as regards bovine herds (notified under document number C(2003) 1925) (Text with EEA relevance) (2003/467/EC)

Cvetnic Z, Spicic S, Katalinic-Jankovic V et al (2006) Mycobacterium caprae infection in cattle and pigs on one family farm in Croatia: a case report. Vet Med Praha 51:523

EC No 854/2004 Regulation (EC) No 854/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 laying down specific rules for the organisation of official controls on products of animal origin intended for human consumption

EFSA (2011) EFSA Panels on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ), on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM), and on Animal Health and Welfare (AHAW); Scientific Opinion on the public health hazards to be covered by inspection of meat (swine). EFSA J 9:198. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2351

EU 2019/627 Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/627 laying down uniform practical arrangements for the performance of official controls on products of animal origin intended for human consumption in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2017/625 of the European Parliament and of the Council and amending Commission Regulation (EC) 2074/2005 as regards official controls

EU No 219/2014 Commission Regulation (EU) No 219/2014 of 7 March 2014 amending Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 854/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the specific requirements for post-mortem inspection of domestic swine

Evira (2015) Post mortem meat inspection of domestic swine [Kotieläiminä pidettävien sikojen post mortem-tarkastus]. Evira Guidance 16041/1

Felin E, Jukola E, Raulo S et al (2016) Current food chain information provides insufficient information for modern meat inspection of pigs. Prev Vet Med 127:113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2016.03.007

Ghidini S, Zanardi E, Di Ciccio PA et al (2018) Development and test of a visual-only meat inspection system for heavy pigs in Northern Italy. BMC Vet Res 14:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-1329-4

Heinonen M, Bergman P, Fredriksson-Ahomaa M et al (2018) Sow mortality is associated with meat inspection findings. Livest Sci 208:90–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2017.12.011

Hill A, Brouwer A, Donaldson N et al (2013) A risk and benefit assessment for visual-only meat inspection of indoor and outdoor pigs in the United Kingdom. Food Control 30:255–264

Kruse AB, Larsen MH, Skou PB, Alban L (2015) Assessment of human health risk associated with pyaemia in Danish finisher pigs when conducting visual-only inspection of the lungs. Int J Food Microbiol 196:32–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.11.017

Luukkanen J, Kotisalo N, Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Lundén J (2015) Distribution and importance of meat inspection tasks in Finnish high-capacity slaughterhouses. Food Control 57:246–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.03.044

Matlova L, Dvorska L, Ayele WY et al (2005) Distribution of Mycobacterium avium complex isolates in tissue samples of pigs fed peat naturally contaminated with mycobacteria as a supplement. J Clin Microbiol 43:1261–1268. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.43.3.1261-1268.2005

Mousing J, Kyrval J, Jensen TK et al (1997) Meat safety consequences of implementing visual postmortem meat inspection procedures in Danish slaughter pigs. Vet Rec 140:472–477. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.140.18.472

Pacheco G, Kruse AB, Petersen JV, Alban L (2013) Assessment of risk associated with a change in meat inspection—Is mandatory palpation of the liver and lungs a necessary part of meat inspection in finisher pigs? Danish Agriculture and Food Council. 64 pp. https://lf.dk/aktuelt/publikationer/svinekod. Accessed 5 Dec 2019

Pakarinen J, Nieminen T, Tirkkonen T et al (2007) Proliferation of mycobacteria in a piggery environment revealed by mycobacterium-specific real-time quantitative PCR and 16S rRNA sandwich hybridization. Vet Microbiol 120:105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.10.016

Pointon A, Hamilton D, Kiermeier A (2018) Assessment of the post-mortem inspection of beef, sheep, goats and pigs in Australia: approach and qualitative risk-based results. Food Control 90:222–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.02.037

Rodríguez S, Bezos J, Romero B et al (2011) Mycobacterium caprae infection in livestock and wildlife, Spain. Emerg Infect Dis 17:532–535. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1703.100618

Stärk KDC, Alonso S, Dadios N et al (2014) Strengths and weaknesses of meat inspection as a contribution to animal health and welfare surveillance. Food Control 39:154–162

Tirkkonen BT (2017) Porcine mycobacteriosis caused by Mycobacterium avium subspecies hominissuis. Dissertationes Schola Doctoralis Scientiae Circumiectalis, Alimentariae, Biologicae, University of Helsinki, 44 pp. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-51-3508-7. Accessed 5 Dec 2019

Tongue SC, Abascal RO, McCrone I, et al (2013) Trial of visual inspection of fattening pigs from non-controlled housing conditions. Scotland’s Rural College, Inverness, Scotland, UK. Report number 2064957 (FS145003) 40 pp

United States Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service (2016) Final report of an audit conducted in Denmark May 23 to June 10, 2016 evaluating the food safety systems governing meat products exported to the United States of America. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/wcm/connect/c075889b-5901-4e19-a9cb-5b82de4b2a8b/2016-Denmark-FAR.pdf?MOD=AJPERES. Accessed 5 Dec 2019

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Helsinki including Helsinki University Central Hospital. We gratefully acknowledge the veterinarians and official auxiliaries for participating in this study. This survey did not receive external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Laukkanen-Ninios, R., Rahkila, R., Oivanen, L. et al. Views of veterinarians and meat inspectors concerning the practical application of visual meat inspection on domestic pigs in Finland. J Consum Prot Food Saf 15, 5–14 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00003-019-01265-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00003-019-01265-x