Abstract

The management of airborne emissions from silicon and ferrosilicon production is, in many ways, similar to the management of airborne emissions from other metallurgical industries, but certain challenges are highly branch-specific, for example the dust types generated and the management of NO X emissions by furnace design and operation. A major difficulty in the mission to reduce emissions is that information about emission types and sources as well as abatement and measurement methods is often scarce, incomplete and scattered. The sheer diversity and complexity of the subject presents a hurdle, especially for new professionals in the field. This article focuses on the airborne emissions from Si and FeSi production, including greenhouse gases, nitrogen oxides, airborne particulate matter also known as dust, polyaromatic hydrocarbons and heavy metals. The aim is to summarize current knowledge in a state-of-the-art overview intended to introduce fresh industry engineers and academic researchers to the technological aspects relevant to the reduction of airborne emissions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Elemental silicon is often referred to as “silicon metal” although it is not a true metal but a semi-metal (metalloid). “High-silicon alloys” typically denote silicon-containing alloys in which silicon dominates the behavior in the production furnace. This normally includes metallurgical grade silicon (MG-Si) with 96–99% purity and ferrosilicon (FeSi) with a silicon content of 65–90%.1 – 3

Table I shows the world production of silicon alloys in recent years. In 2015, an estimated 68% of the global high-silicon alloy production was produced in China.4

In Europe, emissions and waste associated with the production of silicon and ferrosilicon are regulated at both national and EU levels, and there are similar divisions between state/territorial and federal legislations in the USA, Canada and Australia. Some of the national environmental agencies offer guidelines and recommendations, published to complement and detail the legal requirements of this industrial branch.6 – 10 Throughout this article, Norwegian legislation and practices are often cited because they are among the most stringent and comprehensive sets of rules. In some countries, emission data are made publically available through annual publications in open databases.11 – 14

The management of airborne emissions from silicon production is, in many ways, similar to the management of airborne emissions from other metallurgical industries, such as other smelters, foundries and electrochemical metal production. Nonetheless, certain challenges are specific to the silicon alloy-producing industry, for example, the specific dust types and the management of NO X emissions. A commonly encountered difficulty in the mission to reduce emissions is that information on emission types and sources as well as abatement and measurement methods is often scarce, incomplete and scattered. Much progress in emission abatement has been achieved in the industry itself over the last decades, but such work is rarely published. At best, it may be partially presented at industry-specific conferences or in confidential reports, producing little or no documentation available through database search engines. When the industry cooperates with research institutions, journal articles are published within a vast range of different scientific fields, such as atmosphere and aerosol physics, chemistry, process metallurgy, occupational hygiene and environmental monitoring. The sheer diversity and complexity of the subject presents a hurdle, especially for new professionals in this field.

The aim of this literature review is to summarize current knowledge on emission types and concentrations, as well as suitable measurement techniques developed in and relevant to the Si- and FeSi-producing industry. It is an attempt to create a state-of-the-art overview, which can introduce researchers, engineers and others to the relevant technological aspects. The focus of this article is the airborne emissions of particular significance to the silicon industry, including greenhouse gases (GHG), nitrogen oxides (NO X ), particulate matter (PM), polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) and heavy metals.

Silicon Production and Emissions

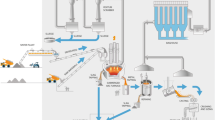

The submerged arc furnace (SAF) is the core process for silicon production. Figure 1 schematically illustrates the production process steps and emission sources.

The primary raw material for silicon production is quartz. The reductants include coal, charcoal, wood chips and sometimes coke. In addition, iron pellets or sinter are included in the raw materials for ferrosilicon (FeSi). The raw materials and reductants are crushed and weighed before they are charged to the furnace. The high-temperature process continuously consumes the carbon-based electrodes. Both ferrosilicon (FeSi) and metallurgical grade silicon (MG-Si) are typically produced this way and the product is hereafter simply referred to as the “silicon alloy”.

While the overall carbothermic reduction reaction of quartz in the furnace may be expressed as;

the furnace is often described as a reactor consisting of two zones; an inner (lower) hot zone and an outer (upper) colder zone. In the hot zone, liquid Si and SiO gas are produced at temperatures around 2000°C through various sub-reactions, giving different stoichiometric versions of the overall reaction:

In the outer zone, SiO ascending from the inner (lower) hot zone reacts with carbon materials according to:

and condenses, depending on temperature, according to either:

or:

Furnace operation and raw material properties will determine the Si yield, i.e. how much SiO gas leaves the furnace. This will, in turn, affect the composition of the furnace off-gas. The raw silicon alloy produced in the furnace hot zone is tapped from the furnace and refined in a slag process before it is cast in molds for cooling. The solidified product is also crushed, sized, weighed and packed at the plant before it is sent to the customer.1 , 15 – 17 The most commonly considered emission types, emission points and their origin, as discussed in this article, are listed in Table II.

While most gases are generated in the furnace itself, dust is generated in almost every step of the silicon production process. The transport and handling of raw materials, reductants and products at ambient conditions generates PM through mechanical impact. Hot processes on the other hand, such as tapping, refining and casting, are sources of thermally generated fumes. Most of the processes are equipped with ventilation systems and the collected off-gases are typically transported through a system of heat exchangers and filters before escaping through the chimney. The furnace dust collected in the filters is commercially termed “micro-silica” and is used in a variety of applications, such as concrete filling.

“Fugitive” or “diffuse” emissions are emissions which do not pass through a stack, chimney, vent, duct or other functionally equivalent opening. Typical fugitive emissions in the metallurgical industry are gases and PM leaking into the working atmosphere from closed or encapsulated processes, where the hoods are not capable of capturing 100% of the emissions.

Gaseous Emissions

Major Greenhouse Gases (GHG)

In the production of silicon alloys, the carbonaceous reductants are usually coal and coke, but bio-carbon (charcoal and wood chips) may also be used. The carbothermic reduction of the quartz to Si will create CO gas through the overall oxide reduction reaction:1

The CO gas will oxidise to CO2 at the furnace charge top in an open or semi-closed furnace. Methane (CH4) and volatile hydrocarbons are also generated in the combustion of the carbonaceous materials and electrodes (pre-baked for MG-Si production and Søderberg-type for FeSi production). Iron-bearing raw materials added as oxides in FeSi production are reduced to metallic iron through the CO gas and the volatile hydrocarbons in the furnace, hence generating CO2. In the top part of the furnace, the Boudouard reaction may also contribute to CO2 emissions:

The extent of GHG emission is highly dependent on:

-

1.

Type of alloy Reduction of quartz requires more energy (i.e. carbon and electricity) than iron oxides, so the higher the Si content, the higher the GHG emissions.

-

2.

Carbonaceous material mix The levels of fixed carbon and volatile matter depend on the choice of carbon materials, which in turn affect GHG emissions. In national emission inventories, only emissions from fossil carbon are accounted for and therefore the use of charcoal lowers the reported specific CO2 emissions.

-

3.

Furnace operation Furnace operation and charging method strongly influence the emissions, in particular of CH4 and NO X . More even charging will generally reduce emissions as compared to batch-wise charging.

The tapped alloy will contain some of the added carbon, mainly in the form of carbides, as the solubility of carbon is generally low compared to other ferroalloys (typically in the order of 0.005–0.02% at 1400–1600°C, depending on the alloy Si content). Typical GHG emissions from this industry have been assessed and documented by a number of authors.18 – 20 The 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories21 and Lindstad et al.22 present a summary of pre-2006 work in terms of general, operation-based and reductant materials-based emission factors. These emission factors are still in use for national GHG inventories.

Typically, most production emissions are reported on the basis of raw material type/use and production tonnage. Then, control measurements are carried out to verify the calculated numbers. Coke and coals are the main contributors to the GHG emissions, but the carbon-based electrodes and electrode paste will also contribute substantially. Typical compositions are shown in Table III which is a summary of data from Lindstad et al.22 Recent, personal communications with the Norwegian industry indicate that the total %C in coal and electrode paste may be approximately 81% and 94%, respectively.23

Based on the above summarised raw material- and production-based emissions, generic (average), total emission factors for different high Si alloys are summarised in Table IV. Note that CH4 emissions based on semi-closed furnaces with the sprinkle charging and off-gas temperatures >750°C are used as default values in these factors.

All hydrocarbon emissions are highly dependent on both alloy type and operation, which in turn lead to high variations and uncertainties of reported data. Lindstad et al.24 estimated typical CH4 emissions for different alloys and furnace operations in the 1990s. Comparing these estimates to the reported CH4 emission values from Norwegian Si and FeSi smelters (available at norskeutslipp.no12 for the period 2002–2014), the discrepancy is of the order of a factor of 10. The reported values are lower than those calculated using emission factors for a given production tonnage. With such large divergences of data, there is undoubtedly room for improvement.

Nitrogen Oxides, NOx

Nitrogen oxides (NO and NO2; often referred to as NO X ) are important emissions due to their role in the atmospheric reactions creating fine particles and ozone smog. NO X emissions also contribute to a suite of year-round environmental problems, including acid rain, eutrophication (stimulated growth of algae and bacteria) and bronchial suffering.

Figure 2 illustrates the temperature dynamics of the three main NO X formation mechanisms compared to typical processes and operation temperatures for silicon alloy production. The fuel and thermal formation mechanisms are the dominant mechanisms in electric arc furnaces producing ferrosilicon and silicon. Fuel NO X is formed by oxidation of the nitrogen components present in the solid fuel, while thermal NO X is formed by direct oxidation of nitrogen (from the air) at temperatures above 1400°C. Such temperatures are frequently observed in the furnace hood.25 – 27

Temperature dependence of NO X formation mechanisms compared to process temperatures in Si production. (Adaptation of original figure by DeNevers28)

Combustion of gaseous SiO above the charge surface and in the tap-hole may locally increase the temperature. The amount of SiO(g) released from the charge will therefore also influence NO X formation, while any SiO reducing measures also seem to reduce NO X emissions. The Norwegian Ferroalloy Association (FFF), SINTEF and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) have collaborated on NO X -reducing strategies for over 20 years and the investments have proven successful.27 , 29 , 30 While some of this work is available through international journals and conference publications, a significant part of the results and achievements remain unpublished. For this paper, we have had the opportunity to read and evaluate some unpublished work in conjunction with the published papers, and we have, with permission from the authors and industrial partners, chosen to include brief summaries of some of the major, unpublished findings and conclusions in this field.

Research initiatives have both focused on waste gas dynamics in general31 and NO X emissions in particular (see also Table V; Fig. 4).32 Efforts to understand the NO X formation have shown that furnace design and furnace operating procedures, such as stoking and charging, heavily influence NO X emissions.33 – 39 Reported NO X emission values vary greatly, with typical values ranging from 500 to 1500 ton per site and year.12 The NO X production is inversely proportional to the silicon yield (low Si yield, high SiO losses), at least up to a certain level of silica fume formation. NO X also forms during tapping, when an oxygen lance is used to open up the tapping channel to increase the metal flow out of the furnace.26 , 40 , 41 The general correlation between SiO and NO X emission is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Correlation between furnace emissions of NO X gas and SiO2 fume with simultaneous temperature measurements (reproduced with permission from Grådahl et al.25)

The NO X formation is also correlated to the moisture content of the furnace gas.42 , 43 Moisture is introduced through the raw materials and, hence, will vary throughout the materials charging cycle. It is well documented that the injection of water vapor into a combustion engine increases the heat capacity (C P ) of the off-gas, so that the temperature cannot exceed the limit for thermal NO X production.44 – 46 Although not validated, it is likely that this effect, in part at least, explains the observations made in high silicon alloy production.27 , 42 , 43

The effect of the furnace hood design and the inlet for false air on the NO X emission has been thoroughly studied and modeled by Kamfjord26 and others,47 – 49 but most of this work is not published. The main conclusions from the unpublished reports are that the amount of air and its flow path throughout the hood determines when, where and whether oxygen and nitrogen are mixed for a sufficiently long time in a sufficiently hot zone to produce NO X . Optimization of furnace hood designs is very complex and the trial-and-error approach is both time- and cost-consuming. Therefore, modeling capabilities are extremely valuable. A modeling concept for predicting turbulent flows, heat transfer, combustion and NO X formation in the furnace hood of a typical submerged arc furnace where silicon or ferrosilicon is produced has been developed. Currently, it is not accurate enough to calculate the true NO X emissions, but it can predict whether it increases or decreases when changes are made in the design or process operations.50 – 55

Primary strategies for NO X reduction includes modifications to the furnace operation, process management and/or the SAF system itself.56 – 58 For silicon alloy production, this means:40 , 59

-

Reducing the combustion temperature through active cooling of the primary flame zone.

-

Avoiding the “blowing” of SiO-rich gas up through the charge surface.

-

Frequent stoking and semi-continuous charging. Grådahl et al.25 found that it was possible to reduce NO X emissions from poorly operated furnaces by 50% if best practices were implemented.

-

Recycling the flue gas to reduce excess air above the charge.

Secondary strategies includes chemical reduction treatments for the flue gas from the furnace, such as selective catalytic or non-catalytic reduction with ammonia (NH3) or urea (CO(NH2)2),60 as used in steel production.61 To date, there is no literature on the use of secondary methods for silicon alloy production, and the effect of such chemical treatments on the silica fume quality is therefore unknown.

SO X , Dioxin, and Other Gases

A great number of gases may be present in the furnace flue gases, some of which are regularly measured while some are more occasionally detected and documented. Examples of such gases include sulfur oxides (SO X ) and other compounds such as H2S and various volatile organic compounds (VOC).1 , 62

SO X emissions are often mentioned as a type of gaseous emissions which occurs in the silicon alloy industry, but very few authors seem to have specifically studied these emissions. The origin of SO2 gas is the sulfur content of the raw materials, primarily reductants, and the reported emissions levels are typically calculated based on material balances. While abatement methods for post-filter cleaning of SO2 are available, the current installation rate is primarily inhibited by investment costs.59 Grådahl et al.25 showed the correlation of SO2 and CO gas emissions with certain furnace events called “avalanches” (collapse of charge burden near the electrodes), the occurrence of which could be reduced by use of semi-continuous charging procedures. The reported SO2 emissions from silicon alloy production are typically of the same order of magnitude as the NO X emissions.1 , 12 Table V illustrate typical values of NO X and SO X off-gas concentrations, varying with furnace and product type. The values presented in the Table are averaged means of several measurements on different furnaces performed irregularly over some 20 years (1995–2016). Only a small fraction of the data has been previously published.25 , 27 The measurement campaigns were carried out by SINTEF, NTNU and FFF in Norway, The results were compiled by S. Grådahl at SINTEF for the sake of this article, and the data are published with permission from FFF.

Dioxins are a class of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) which are highly toxic to human health. Like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), dioxins may be both gaseous and particle-bound, depending on temperature. The generation of dioxins in combustion and metallurgical processes is, in a general sense, quite well established.63 , 64 , 25 The destruction of dioxins and organic compounds, such as furans and PAH’s, at high temperatures allow for efficient reduction or even elimination in modern, semi-closed SAFs. Furnace design and operation are keys and can be optimized for close control of the flue gas temperature, see Fig. 4. Tveit et al.59 suggest that the use of a heat exchange system (where off-gases are effectively cooled, post-furnace, in a steam boiler) will allow for higher off-gas temperatures and therefore have the same reducing effect on this type of emissions.

Off-gas emissions of PAH, dioxin and NOx for (A) a batch-fed, open SAF, (B) a semi-closed SAF with semi-continuous charging and (C) a semi-closed SAF with semi-continuous charging and off-gas temperatures >800°C (reproduced with permission from Grådahl et al.25)

Particle-Bound Gaseous Compounds

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, PAH

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) consist of organic structures having more than two joined aromatic (benzene) rings. Anthropogenic PAHs are typically formed by incomplete combustion of organic materials like oil, wood, or garbage. The lighter compounds, with few aromatic rings, are gaseous at room temperature whereas the larger molecular compounds are liquid or solid and commonly adsorbed on particles, for example, soot. PAHs belong to the Persistent Organic Pollutants (POP), a group of airborne emissions which are particularly resistant to degradation. Some of the PAH compounds are linked to various forms of cancer and the US Environment Protection Agency (EPA) has identified 16 priority PAHs, based on their potential to induce adverse environmental and health effects. The main sources of PAH in silicon alloy production is the combustion of reductants in the furnace and the baking of electrodes. Typical PAH and NO X emissions for different furnace operations are listed/plotted in Fig. 4. Reported PAH values from Norwegian plants range from 10 to 70 kg per site and year. PAH emissions from industrial sites are estimated by use of emission factors.65 – 70

PAH formation is linked to soot formation which in turn is influenced by furnace design and operation and varies throughout the charging cycle.59 As PAHs are destroyed at high temperatures, emissions can be significantly reduced by increased off-gas temperatures as illustrated in Fig. 4 by Grådahl et al.25 The reference case (A) represents a traditional open furnace with batch charging. The second case (B) is a semi-closed furnace, with feeding tubes through which the raw materials were fed semi-continuously (every minute). Case (C) represents the semi-closed furnace with average off-gas temperatures raised from 635°C to 812°C. The increased temperature leads to the destruction of PAH and dioxin but may also increase the formation of thermal NO X .

Heavy Metals

Heavy metals enter the production process as trace elements in the raw materials and electrodes and are redistributed to metal, slag, fume and gas. The concentrations depend on the alloy composition and the process temperatures. At temperatures of 1600°C or higher, certain metals such as Zn, Pb, Cd, Na, Mn and Fe go into the gas phase and may escape as metal vapor. When the off-gas temperature drops, the metal vapors are condensed and therefore often collected with the dust. Myrhaug and Tveit71 , 72 showed that a boiling point model can be used to predict the redistribution of an element in the furnace, as shown in Fig. 5. Næss et al.73 showed that the model is also applicable to the refining ladle, with some modifications due to the oxidation of elements, as shown in Fig. 6.

Distribution of trace elements from SAF (reproduced with permission from Myrhaug and Tveit71)

Distribution of trace elements from the gas-blown refining ladle (reproduced with permission from Næss et al.73)

The Norwegian legislation for heavy metal emissions appears to be one of the most rigorous in the world, requiring emission control of 11 trace elements for silicon alloy production facilities. These trace elements are: As, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Hg, Mo, Ni, Pb, Se and Zn. The European, USA and other partners to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) have put special emphasis on lead, cadmium and mercury.74 The reported emissions of trace elements are often based on material balances and may vary greatly between plants, but an example is shown in Table VI.59

Mercury constitutes a special case among the airborne heavy metal emissions as international legislation has long been stringent with respect to this metal.75 In silicon alloy plants, the particulate control devices (e.g., fabric filter or wet scrubber) capture the particle-bound mercury. The more volatile elemental mercury is emitted to the atmosphere if no further gas treatment is applied. Hg and Cd levels in the off-gas may be reduced by the use of bag filters with an adsorbent injection (such as activated carbon or lignite coke).8 , 76 , 77

Emission estimates to air through the filter systems must cover both gaseous and particle-bound heavy metals, but a major challenge for the estimation is the low concentrations of these elements in the material flows. Mercury typically has detection limits (DL) given in units of parts per billion (ppb) whereas the other heavy metals have DL of the order of magnitude of parts per million (ppm). Hence, very significant measurement uncertainties are introduced and it is often impossible to “close” the material balance for individual elements. The total uncertainty for elements such as Co, Hg and Mo is often around or above 100%. These uncertainties may be lowered by continuous, on-line measurements after the filter systems, but such measurements are often practically challenging. Additionally, large uncertainties are also related to sampling and representability.73 , 78

Particulate Emissions

Airborne PM is an important constituent in the diffuse emissions escaping the plants and may not only affect the air quality inside the plant but also in the local, urban communities as well as the environment at large. The PM may be harmful if inhaled and exposure to high levels of particles has been linked to cancer, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other respiratory and cardiovascular syndromes.79 – 86

Almost all processes involved in silicon alloy production produces PM in some form. In this article, the terms particulate matter and dust are used as synonyms and primarily used for solid particles. The term aerosol includes both liquid and solid particles and the term fume relates to thermally generated aerosols. Table VII provides an overview of the PM sources and a rough estimate of their relative importance to indoor air PM concentrations and to PM emissions from the plant.8 , 26

The furnace generates most of the PM, through combustion of escaping SiO gas from the furnace hot zone to SiO2 above the charge surface. A typical metal yield of between 80% and 90% means that up to 10–20% of incoming Si-units in the furnace escape as fumed silica. Modern ventilation and filter systems have enabled efficient collection of this type of dust and it even constitutes a profitable by-product (microsilica). A typical Norwegian PM emission limit is approximately 30 mg/Nm3. The characteristics of microsilica have been described in the literature as agglomerates of amorphous silica spheres.71 , 87 , 88

The PM in the silicon alloy industry includes both fine (FP) and ultrafine particles (UFP), i.e. particles with aerodynamic diameters of <2.5 µm and <0.1 µm, respectively. UFPs represent a rather special case of particulate matter as the large surface area implies higher reactivity and different physico-chemical properties than the larger particles.89 – 91 Current administrative norms as well as other limits are established in mass concentrations, but UFPs make little contribution to the mass concentration.92 – 94

Measurements of dust and NO X above the furnace charge and in the off-gas show strong correlations. The SiO “combustion” is a highly exothermic reaction which produces high-temperature zones locally. In these high-temperatures zones, thermal NO X production is promoted (see the NO X section).26 , 95

It is clear from Table IV that the major sources of PM, both inside the plant and escaping from the plant, are those which involve the liquid alloy. Tapping, refining, casting and other operations where high-temperature liquid alloy is in contact with air produces a silica fume which has many similarities to the microsilica.26 , 73 , 78 , 92 , 93 , 96 , 97 Figure 7 shows an SEM picture and an ELPI particle size distribution for thermally generated fume particles from ferrosilicon tapping. Naess et al.96 , 98 studied the process by which this type of silica dust forms, and concluded that the main dust formation mechanism is the active oxidation of the liquid silicon alloy, while a small fraction (<1%) of the dust particles would form by splashing (droplet expulsion).97 The active oxidation was found to occur in two steps in which the silicon would first react with oxygen to form SiO gas which would then oxidize further to SiO2.97 , 99 – 101 The kinetics of this process is governed by oxygen access to the alloy surface, and therefore highly dependent on the dynamics of the alloy surface exposed to the air.102 , 103 Depending on the gas flow rate, a refining ladle for MG-Si generates 0.8–1.7 kg SiO2 per ton Si.

Fume from FeSi furnace tapping area. (a) Scanning electron micrograph of the fume particles. (b) Particle size distribution as measured by an electrical low pressure impactor (reproduced with permission from Kero et al.93)

The dust from the handling and transport of solid materials, such as the product and the raw materials, is fundamentally different from the dust generated by the active oxidation. It is typically coarser, and the physical and chemical properties depend on the material from which it was generated. Raw material handling and transport can, for example, produce airborne crystalline alpha-quartz which is a health hazard in its own right. No literature on the generation, collection and reduction of the mechanically generated PM in high-Si alloy smelters has been found.

Emission Measurement Techniques

Off-gas monitoring in MG-Si and FeSi production is connected to a couple of specific challenges compared to emission measurements in other industries. The gas temperature in proximity of the furnace is very high, as illustrated in Fig. 2 and this constitutes a major difficulty, as described below. Another difficulty is the high PM concentrations before the filter. The wear on instruments installed in particle-laden gas streams is considerable, and material deposits on the instruments risk completely off-setting the results obtained in such conditions. In addition, data handling and the interpretation of results is made difficult by the varying conditions caused by the industrial operation.

The IPPC BREF documents10 offer some general guidelines for emissions monitoring. Timing considerations, such as averaging time and sampling/data collection frequency, are of prime importance and depend heavily on the processes. Hence, process understanding is essential. Figure 8 gives an overview of the variety of measurement methods available for airborne emissions. A bordering field of science is that of occupational hygiene, a topic which is outside the scope of this article and will not be covered here. Hence, only measurement methods using stationary devices will be described.

The concentration of the detected pollutant is read as a function of time with in situ, direct-reading or in-line instruments. They operate in real time and are often equipped with data logging. Indirect instruments are samplers which collect the pollutant over a certain time interval with subsequent laboratory analysis. This is sometimes referred to as ex situ analysis. Active or extractive sampling refers to the use of a pump to draw the polluted air into the instrument whereas passive methods operate without alteration of the air flow.10 , 104 , 105

In addition to in situ and extractive measurements, the materials balance (process- or site-specific mass flow calculations) are often carried out to estimate the emissions of, for example, heavy metals and CO2.

To report the correct emissions of the different components, representative flow measurement in the off-gas channel is an essential complement to correct concentration measurements. Different measuring principles are used, like pitot tubes, annubars, orifice plates, ultrasonic flowmeters and thermal mass flow meters. Extractive measurement techniques applied to off-gas ducts and pipes often call for isokinetic sampling and/or dilution, which can be extremely challenging in terms of practical operation. Both procedures will also, inevitably, introduce additional error sources and increase uncertainty, especially under the non-ideal conditions of industrial operations.105 – 107

Gas Measurements

Round-the-clock gas measurements are desirable, but may be difficult to achieve in high-temperature dusty gas streams. Most melting plants have no chimney after the baghouse filter and, therefore, all the gas measurements have to be done in the duct before the filter. This is an extremely harsh environment and continuous measurements are therefore very challenging. Optical sensors are the first choice, typically recommended for most continuous industrial measurement applications, but their use is often limited by high gas temperatures. Instruments based on extractive principles will automatically decrease the gas temperature (as the gas is drawn out of the duct) which enables more straightforward detection of gas species. The high dust load in the furnace off-gas will, however, be very challenging for most of the commercially available devices. Nonetheless, these types of instruments are frequently used in the industry today, albeit not often for continuous measurements. The second-best option is systematic measurements for some hours at a time. This is the most common industrial approach for gas component measurements in off-gas from silicon alloy production.

In situ Measurements

In situ gas analyzers measure the gas directly inside a duct or across an open path (0–500 m) with very short response times. The measuring principle is usually some form of optical spectroscopy, often ultraviolet (UV) or infrared (IR). In smelters, the instruments are selected based on their ability to operate in hot, dirty and dusty gas conditions.

The tunable diode laser (TDL) has become standard instrumentation for NO measurements at most Norwegian plants,25 , 108 and can be used in off-gas ducts prior to the baghouse filter, despite the high temperatures and high dust concentrations. It can detect many different gas species including NO, H2O, NH3, HCl, and HF in a gaseous mixture if coupled with laser absorption spectrometry (TDLAS). The advantage of TDLAS over other techniques for concentration measurement is its ability to achieve very low detection limits and very short response time.

Extractive Gas Sampling Devices

Extractive techniques are acceptable for quantification of non-reactive gas species, such as NO, CO and CO2, as they may be allowed to cool down before detection. Species like HCl, SO2 or H2O, however, have to be kept at a constant, high temperature which may be achieved by an electrically heated sample hose.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) devices have been tested and proven useful in ferroalloy industries in spite of the harsh conditions.42 , 43 Several gas species may be detected simultaneously as well as solid or liquid aerosols, but components with a symmetrical electron binding cannot be assessed. Grådahl et al.109 showed that an FTIR (with in-house analysis software) can be used over an open-path, such as a slag-pit, in ferroalloy smelters.

For gas components with a symmetrical electron binding (such as H2, N2 and O2), mass spectrometry (MS), gas chromatography (GC) or Raman spectroscopy may be used, but these methods tend to have slow response times. Promisingly, Kjos et al.110 demonstrated the industrial relevance of a combined GC–MS instrument in flue gas from aluminum electrolysis and was able to detect very low (sub-ppb) concentrations.

PM Measurements

While many different measurement techniques offer the ability to characterize and quantify the airborne particulate matter, very few of the commercially available instruments are tested in industrial melting plants or validated for the specific types of PM encountered there. PM characteristics, such as optical properties, sizes, shapes, density, etc., may heavily influence the measurements, and site-specific calibrations are typically necessary to ensure reasonable accuracy.

Airborne particulate matter is often classified by the aerodynamic diameter (D p ) of the particles, but the terminology is far from unambiguous. In occupational hygiene and medicine, exposure terminology is based on how the aerosols may penetrate the body through the respiratory system. It is then common to distinguish between the inhalable, thoracic and respirable fractions where the term “respirable” indicates that the aerosol may penetrate the body all the way down to the alveolar region of the lungs.105 , 107 Another common and more technical terminology for airborne particulate matter is based on the so-called PM standards. For example, PM10 refers to all aerosols with D p < 10 µm and PM2.5 refers to the concentration (in total mass per unit volume of air) of particles with aerodynamic diameter <2.5 µm. PM2.5 is a subset of PM10 and is sometimes referred to as fine particles.104 , 107 , 111 Yet other terminologies exist and are used in parallel with the aforementioned ones in the literature. For instance, Preining112 defines the terms fine, ultrafine (UFP) and nanosized (NP) as particles with D p < 750 nm, D p < 100 nm and D p < 25 nm, respectively.

In situ PM Measurements

Passive instruments are typically long-range instruments for measuring across a gas stream in a duct. These are typically laser-based instruments and other optical sensors. Such instruments have been used in the silicon alloy industry to assess fuming rates,78 , 97 and to continuously monitor PM emissions as well as workplace atmosphere.113 For roof measurements, Grådahl et al.113 recommends the use of directional anemometers (able to detect not only wind speed but also direction) in combination with long-range, open-path devices.

Unpublished reports,114 – 116 however, emphasise a need for site-specific calibration which can be performed using gravimetric filters. A number of filter cassettes are then mounted on wires along the laser line-of-sight, and the mass readings of the lasers are compared and adjusted to the dust mass collected by the filters as a means for calibration. Several reports indicate that, without such calibration, the optical instruments are not reliable for concentration measurements but may still be useful for relative measurements for improved process understanding and control.

Extractive PM Measurements

Extractive measurements on hot, particle-laden or otherwise dirty off-gases typically require dilution of the gas stream before it enters the sensitive instrument. Dilution may, however, be challenging in terms of practical operation and also introduces additional error sources with significant implications for data treatment and calibration. The purpose of the dilution is typically two-fold: first, to cool the gas stream to temperatures that can be handled by the instrument; and second, to dilute the particle concentration to a level which can be detected and/or quantified by the instrument and/or avoid condensation or clogging inside the instrument. The cooling in itself introduces error sources such as potential condensation of gases into aerosols and deposition of substances onto surfaces inside the instrument.104 , 105 , 117

A number of extractive methods for PM quantification have been tested in the silicon alloy industry, including gravimetric filters, optical devices, mobility sizers and impactors. Gravimetric filters offer a robust, cheap and simple way to assess PM weight concentration.104 , 113 A standard optical particle counter (OPC) and a condensation particle counter (CPC) appear to be less useful in silicon plants as they detect too-low PM concentrations.94 , 113 Mobility particle sizers 117 , 118 and electrical low-pressure impactors (ELPI)92 – 94 appear better suited for PM measurements in silicon plants, although these instruments are larger, heavier and more cumbersome to operate. Data interpretation is also more challenging, especially for the ELPI.119 – 121

Conclusion

In this literature review, current knowledge developed in, and relevant to, the Si- and FeSi-producing industry has been summarized. The article is primarily based on information available in the open literature, but some previously unpublished reports, of utmost relevance to the topics, have also been summarized and included. It contains state-of-the-art overviews for gaseous and particle-bound airborne emissions. Relevant technological aspects for the control and reduction of GHG, (NO X ), (PAH), heavy metals and PM are introduced.

A number of research areas that need prioritized consideration have been identified:

-

Emissions of GHGs other than CO2, such as hydrocarbons. For methane, the discrepancy between the very limited reported emission data and emissions calculated by standard emission factors is of the order of a factor of 10.

-

The use of chemical NO X reduction treatments for SAF off-gases and the potential effect of such treatments on the silica fume quality.

-

The mechanical generation of dust from handling and transport of raw materials as well as solid products has not been studied. Effective methods for the collection and reduction of such dust are needed.

Most gaseous emissions are reported and monitored by use of emission factors. The overall GHG emissions from FeSi and MG-Si production are reasonably well understood and quantified, with the exception of hydrocarbons. The extent of GHG emissions is highly dependent on the carbon and electricity consumption (which in turn depends on the type of Si/FeSi alloy), the carbonaceous material mix, charging methods and furnace operation. The furnace design, flue gas management and furnace operating procedures, such as stoking and charging, heavily influence NO X emissions. Measurements show strong correlations between PM and NO X formation above the furnace charge. Localized temperature control can only be achieved by limiting the extent of silica fume production through SiO(g) combustion.

Close flue gas temperature control is extremely important for several reasons. One reason is the delicate trade-off between PAH and NO X management. PAHs are destructed at high temperatures, and PAH emissions can be significantly reduced when off-gas temperatures are kept above 800°C.

PAH and heavy metals are simultaneously present as gases and particulate forms, and their distribution is highly temperature-dependent. The particle-bound compounds are often collected in the particulate control devices (e.g., fabric filter or wet scrubber). The more volatile compounds, however, will risk being emitted to the atmosphere if no further gas treatment is applied, for example, by the use of bag filters with adsorbent injection to remove Hg and Cd.

It is particularly important to consider uncertainty parameters arising from every step of the monitoring process, yet their estimation is often less than trivial. Accuracy and sample representability are often limiting the trustworthiness of the obtained data. The use of material balances are, for example, sensitive to representability issues, and heavy metals assessment is highly uncertain due to the detection limits of currently available analysis methods. For flue gas measurements, averaging time and frequency are of prime importance, and such timing requirements always depend heavily on the processes at hand. Solid process understanding is therefore essential if useful data are to be produced.

Round-the-clock gas measurements are desirable, but may be difficult to achieve in high-temperature dusty gas streams. Smelter flue gas ducts present an extremely harsh environment where sampling is very challenging and the available instruments must be selected based on their ability to operate under such conditions. Dilution and isokinetic sampling requirements may present additional difficulties and typically increase uncertainty values. PM measurement principles often remain to be validated for the specific types of dust encountered in Si and FeSi smelters. Hence, site-specific calibrations are recommended to ensure reasonable accuracy.

References

A. Schei, J.K. Tuset, and H. Tveit, Production of High Silicon Alloys, 1st ed. (Trondheim: TAPIR Forlag, 1998).

R.I.S. Ltd, Silicon Market Overview; MMTA Market Overviews. Minor Metals Trade Association. Accessed 1 February 2016.

M. Tangstad, eds., Metal Production in Norway (Trondheim: Akademika Publishing, 2013).

E.K. Schnebele, Report No. ISBN 978-1-4113-4011-4, Silicon (Reston, Virginia: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, 2016).

L.A. Corathers, Report No. ISBN 978-1-4113-3765-7, Silicon (Reston, Virginia: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, 2014).

Environmental Code of Practice for Base Metals Smelters and Refineries. Environment & Climate Change Canada, Quebec, 1999.

National Pollutant Inventory (NPI) Guide. Department of the Environment, Canberra, 2015.

Best Available Techniques (BAT) Reference Document for the Non-ferrous Metals Industries. Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control (IPPC), 2014.

Emission Estimation Technique Manual for Non-ferrous Metal Manufacture. National Pollutant Inventory (NPI), Canberra, 2001.

Reference Document on the General Principles of Monitoring (BREF MON). Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control (IPPC), 2003.

European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (E-PRTR), The European Environment Agency (EEA). http://prtr.ec.europa.eu/#/home. Accessed 29 March 2016.

Total Emissions to Air in Norway—The Norwegian PRTR, The Norwegian Environment Agency. http://www.norskeutslipp.no/en/Frontpage/?SectorID=90. Accessed 1 February 2016.

National Pollutant Inventory (NPi), The Australian Government, Department of the Environment. http://www.npi.gov.au/. Accessed 29 March 2016.

National Pollutant Release Inventory (NPRI)—Tracking Pollution in Canada, Government of Canada, Department of Environment and Climate Change. http://www.ec.gc.ca/inrp-npri/. Accessed 29 March 2016.

Z. Jin, Carbon Behaviour During Si Production (Trondheim: Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2013).

E. Ringdalen and M. Tangstad, International Smelting Technology Symposium: Incorporating the 6th Advances in Sulfide Smelting Symposium, Orlando, Florida, 2012, pp. 195.

G. Tranell, M. Andersson, E. Ringdalen, O. Ostrovski, and J. Steinmo, INFACON XII, Helsinki, 2010.

T. Lindstad, Report No. STF80A04019, CO 2 Emissions from the Production of Silicon Alloys (Trondheim: SINTEF, 2004).

B.E. Monsen, T. Lindstad, and J.K. Tuset, ISS Electric Furnace Conference, 1998, pp. 371.

B.E. Monsen, Report No. STF24 A98537, CO 2 Emission Factors for Metallurgical Industry and Cement Production. 2nd Part: Production of Ferrosilicon and Silicon Metal in Norway (Trondheim: SINTEF, 1998).

S. Eggleston, L. Buendia, K. MIwa, T. Ngara, and K. Tanabe, eds., Industrial Processes and Product Use. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), vol. 3. (Hayama: Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), 2006).

T. Lindstad, S. Olsen, G. Tranell, T. Færden, and J. Lubetsky, INFACON XI, New Delhi, 2007, p. 459.

R. Chapana, Wacker Chemicals AS, Holla, Norway. Electronic Mail Correspondance to G. Tranell and I. Kero, 2016.

T. Lindstad, S.E. Olsen, G. Tranell, T. Færden, and J. Lubetsky, IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories.

S. Grådahl, S. Johansen, B. Ravary, B. Andresen, and H. Tveit, INFACON XI, New Delhi, 2007, pp. 479.

N.E. Kamfjord, Mass and Energy Balances of the Silicon Process—Improved Emission Standards, in Materials Science and Engineering (Trondheim: The Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2012).

E.H. Myrhaug, H. Tveit, N.E. Kamfjord, and G.J. Andersen, Silicon for the Chemical and Solar Industry XI, Bergen-Ulvik, 2012, pp. 95.

N. De Nevers, Air Pollution Control Engineering (Long Grove: Waveland Press, 2010).

P.I. Nikolaisen, Slik kuttet Elkem utslipp tilsvarende 150.000 dieselbiler på rekordtid, in Teknisk Ukeblad (Oslo: Teknisk Ukeblad Media AS, 2014).

H. Tveit and B. Wittgens, Grønnere Metallproduksjon, in Dagens Næringsliv (Oslo: Dagens Næringsliv AS, 2014).

S. Johansen, S. Graadahl, R. Gammelsæter, M. Raanes, A. Arntsberg, T. Lindstad, G. Enstad, and H. Tveit, Smelter Process Gas Handling and Treatment, San Diego, 1992, pp. 7.

S.T. Johansen, H. Tveit, S. Grådahl, A. Valderhaug, and J.Å. Byberg, INFACON VIII, Beijing, 1998.

B. Ravary and S.T. Johansen, 2nd International Conference on CFD in the Minerals and Process Industries, Melbourne, 1999, pp. 6.

N.E. Kamfjord, H. Tveit, and I. Solheim, 3rd International Symposium on High-Temperature Metallurgical Processing, Orlando, FL, 2012, pp. 411.

I. Solheim, R. Jensen, and N.E. Kamfjord, 3rd International Symposium on High-Temperature Metallurgical Processing, Orlando, Florida, 2012.

B. Ravary, C. Colomb, and S. Johansen, INFACON XI, New Delhi, 2007.

B. Panjwani, S. Andersson, and H. Midtdal, 8th International Conference on CFD in the Oil & Gas, Metallurgical and Process Industries, Trondheim, 2011.

I. Solheim and N.E. Kamfjord, INFACON XIII, Almaty, 2013.

Ø. Skreiberg, Report No. SINTEF TR F5652 ISBN 82-594-2314-6, Evaluation of Detailed Gas-Phase Chemical Kinetics Mechanisms for NO X Modelling in Biomass- and MSW Combustion Applications (Trondheim: SINTEF, 2002).

J.E. Olsen, B. Wittgens, S. Grådahl, I. Solheim, and B. Panjwani, Report No. SINTEF A22929 ISBN: 978-82-14-05268-8 Status on NO X -Related Studies for the Norwegian Ferroalloy Industry (Trondheim: SINTEF, 2012).

M. Kadkhodabeigi, Modeling of Tapping Processes in Submerged Arc Furnaces, in Faculty of Natural Sciences and Technology, Department of Materials Science and Engineering (Trondheim: Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2011).

D. Slizovskiy, H. Tveit, I. Brede, G. Tranell, G.J. Andersen, N.E. Kamfjord, and B. Wittgens, Silicon for the Chemical and Solar Industry XII, Trondheim, 2014, pp. 207.

I. Brede, Report No. Master Thesis, Parameters Contributing to the Formation of NO X in the Silicon Furnace: The Effect of the Charging Frequency and Raw Material Composition on the Formation of NO (Trondheim: The Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2013).

M. Ishida, H. Ueki, and D. Sakaguchi, Report No., Prediction of NOx Reduction Rate Due to Port Water Injection in a DI Diesel Engine. SAE Technical Paper, 1997.

K. Kannan and M. Udayakumar, J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 4, 59 (2009).

A. Maiboom and X. Tauzia, Fuel 90, 3179 (2011).

C. Colomb and B. Ravary, Report No. SINTEF STF80MK F05231, Modelling Combustion and Thermal NO X Formation in Electric Arc Furnaces for the Production of Ferro-silicon and Silicon-Metal (Trondheim: SINTEF, 2005).

A. Simonsen, Report No. F7129, 3D CFD Simulation of NO X Combustion—Comparison with Experiments and Evaluation of NO X Reducing Strategies (Trondheim: SINTEF, 2008).

B. Solvang and H. Midtdal, Report No. F16884, A Generic Silicon Furnace Model for the Investigation of NO X Reduction Strategies Using CFD (Trondheim: SINTEF, 2009).

M. Bugge, B. Ravary, Ø. Skreiberg, L. Sørum, and T. Pettersen, Report No. SINTEF TR F 5553 ISBN 82-594-2204-2, A Status on NO X Related to Waste Combustion and Pyro-metallurgical Processes (Trondheim: SINTEF, 2001).

B. Ravary and M. Bugge, Report No. SINTEF STF24 F02579, Description and Analysis of Ferroalloy Processes in Connection with NO X Formation (Trondheim: SINTEF, 2002).

B. Ravary, C. Colomb, and S.T. Johansen, INFACON XI, New Delhi, 2007.

B. Ravary, S. Grådahl, and M. Bugge, Report No. STF80MK F05387, Analysis of NO X Formation in Electric Arc Furnaces Producing Ferro-silicon and Silicon Metal (Trondheim: SINTEF, 2005).

B. Ravary and K. Tang, Report No. SINTEF STF24 F03517 SiO Combustion in Furnaces for Ferroalloy Production and Its Influence on NO X Formation (Trondheim: SINTEF, 2003).

B. Panjwani and J. Olsen, European Combustion Meeting, Lund, 2013.

T. Echterhof and H. Pfeifer, ISIJ Int. 51, 1631 (2011).

T. Echterhof and H. Pfeifer, Metall. Mater. Trans. B 43, 163 (2012).

M. Kirschen, L. Voj, and H. Pfeifer, Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 7, 236 (2005).

H. Tveit, M. Storset, and I.J. Eikeland, Silicon for the Chemical Industry VII (Bergen: MS Trollfjord, 2004), pp. 55.

P. Forzatti, Appl. Catal. A 222, 221 (2001).

E. Chan, M. Riley, M.J. Thomson, and E. Evenson, ISIJ Int. 44, 429 (2004).

H. Tveit and I.J. Eikeland, Silicon for the Chemical Industry IV, Geiranger, 1998, pp. 365.

A. Buekens, L. Stieglitz, K. Hell, H. Huang, and P. Segers, Chemosphere 42, 729 (2001).

B.-W. Yu, G.-Z. Jin, Y.-H. Moon, M.-K. Kim, J.-D. Kyoung, and Y.-S. Chang, Chemosphere 62, 494 (2006).

G.C. Bandeira and H.E. Meneses, eds., Handbook of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons—Chemistry, Occurrence and Health Issues (New York: Chemistry Research and Applications, Nova Science Publishers Inc, 2013).

Y. Zhang and S. Tao, Atmos. Environ. 43, 812 (2009).

P. Boffetta, N. Jourenkova, and P. Gustavsson, Cancer Causes Control 8, 444 (1997).

H.-H. Yang, W.-J. Lee, S.-J. Chen, and S.-O. Lai, J. Hazard. Mater. 60, 159 (1998).

H.-H. Yang, S.-O. Lai, L.-T. Hsieh, H.-J. Hsueh, and T.-W. Chi, Chemosphere 48, 1061 (2002).

K. Ravindra, R. Sokhi, and R. Van Grieken, Atmos. Environ. 42, 2895 (2008).

E.H. Myrhaug and H. Tveit, 58th Electric Furnace Conference and 17th Process Technology Conference Proceedings (Warrendale, PA: Iron & Steel Society, 2000), pp. 591.

H. Tveit and E. Myrhaug, Silicon for the Chemical Industry V (Trondheim, Norway: The Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2000), pp. 23.

M.K. Naess, I. Kero, G. Tranell, K. Tang, and H. Tveit, JOM 66, 2343 (2014).

Aarhus Protocol on Heavy Metals Emissions. UNECE Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution (Aarhus: The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), 1998).

Minamata Convention on Mercury. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Geneva, 2013.

D. Haaland, M. Bruno, and T. Thomassen, INFACON IX—The Ninth International Ferroalloys Congress, Quebec, 2001.

Reference Document on Best Available Techniques in the Non Ferrous Metals Industries. Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control (IPPC), 2001.

M.K. Naess, I. Kero, and G. Tranell, JOM 65, 997 (2013).

H.L. Johnsen, Lung Function, Respiratory Symptoms, and Occupational Exposure, in Fakultetsdivisjon Akershus universitetssykehus (Oslo: University of Oslo, 2009).

H.L. Johnsen, S.M. Hetland, J. Šaltytė Benth, J. Kongerud, and V. Søyseth, Ann. Occup. Hyg. 52, 623 (2008).

H.L. Johnsen, V. Søyseth, S. Hetland, J.Š. Benth, and J. Kongerud, Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 81, 451 (2008).

Å. Hobbesland, H. Kjuus, and D.S. Thelle, Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 23, 342 (1997).

Å. Hobbesland, H. Kjuus, and D.S. Thelle, Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 23, 334 (1997).

V. Søyseth, H.L. Johnsen, M.D. Bugge, S.M. Hetland, and J. Kongerud, Am. J. Ind. Med. 54, 707 (2011).

V. Søyseth, H.L. Johnsen, M.D. Bugge, S.M. Hetland, and J. Kongerud, Occup. Environ. Med. 68, 24 (2011).

V. Søyseth, H.L. Johnsen, and J. Kongerud, Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 19, 158 (2013).

E. Dingsøyr, M. Dåstøl, and W.C. Wedberg, The 5. European Symposium Particle Characterization, Nurnberg, 1992.

H. Kolderup, J. Air Pollut. Control Assoc. 27, 127 (1977).

N. Li, C. Sioutas, A. Cho, D. Schmitz, C. Misra, J. Sempf, M. Wang, T. Oberley, J. Froines, and A. Nel, Environ. Health Perspect. 111, 455 (2003).

C. Monteiller, L. Tran, W. MacNee, S. Faux, A. Jones, B. Miller, and K. Donaldson, Occup. Environ. Med. 54, 609 (2007).

J.H. Vincent and C.F. Clement, Philos. Trans. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 358, 2673 (2000).

I. Kero, M. Naess, and G. Tranell, INFACON XIII, Almaty, 2013, pp. 945.

I. Kero, M. Naess, and G. Tranell, J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 12, 37 (2015).

I.T. Kero and R.B. Jørgensen, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13, 871 (2016).

N.E. Kamfjord, H. Tveit, M.K. Naess, and E.H. Myrhaug, 3rd International Symposium on High-Temperature Metallurgical Processing, Orlando, FL, 2012, pp. 401.

M.K. Naess, Mechanisms and Kinetics of Liquid Silicon Oxidation, in Materials Science and Engineering (Trondheim: Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2013).

M.K. Naess, G. Tranell, J.E. Olsen, N.E. Kamfjord, and K. Tang, Oxid. Met. 78, 239 (2012).

M. Næss, J. Olsen, S. Andersson, and G. Tranell, Oxid. Met. 82, 395 (2014).

M.K. Naess, G.M. Tranell, and N.E. Kamfjord, 2nd International Symposium on High-Temperature Metallurgical Processing (TMS Annual Meeting & Exhibition, San Diego, CA, 2011) pp. 239.

M.K. Naess, D.J. Young, J. Zhang, J.E. Olsen, and G. Tranell, Oxid. Met. 78, 363 (2012).

M.K. Naess, N. Smith, G. Tranell, and J.E. Olsen, INFACON XIII, Almaty, 2013.

J.E. Olsen, M. Næss, and G. Tranell, 8th International Conference on CFD in Oil & Gas—Metallurgical and Process Industries (Trondheim: SINTEF/NTNU, 2011).

J.E. Olsen, M.K. Næss, and G. Tranell, (TMS Annual Meeting, Orlando, 2012).

W.C. Hinds, Aerosol Technology: Properties, Behavior, and Measurement of Airborne Particles, vol. 1 (New York: Wiley, 1982), p. 442.

P. Kulkarni, eds., Aerosol Measurement—Principles, Techniques and Applications (Hoboken: Wiley, 2011).

H. Gaertner, Characteristics of Particulate Emissions from Aluminium Electrolysis Cells, in Materials Science and Engineering (Trondheim: Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2013).

J.H. Vincent, Aerosol Sampling—Science, Standards, Instrumentation and Applications (Chichester: Wiley, 2007).

B. Ravary and S. Grådahl, INFACON XII, Helsinki, 2010.

S. Grådahl, A. Ferber, T. Aarhaug, and A. Brunsvik, Report No. F21050, Measuring Fugitive Emissions at Eramet Kvinesdal (Trondheim: SINTEF, 2011).

O.S. Kjos, T.A. Aarhaug, B. Wittgens, and A. Brunsvik, in Light Metals 2014, ed. J. Grandfield (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2014), pp. 541–546

R. Sarangapani, R. Schlesinger, J. Brown and W. Wilson, Report No Vol I: EPA/600/P-99/002aF, Vol II: EPA/600/P-99/002bF, Air Quality Criteria for Particulate Matter (Triangle Park, NC: National Center for Environmental Assessment Research, 2004).

O. Preining, J. Aerosol Sci. 29, 481 (1998).

I. Kero, S. Grådahl, H. Fardal, and B. Wittgens, Sustainable Industrial Processing Summit (SIPS)—Takano International Symposium on Metals and Alloys, Antalya, 2015, pp. 123.

H. Fardal, Report No. F23807, Measuring of Dust Released from Production of Ferromanganese and Ferrosilicon (Trondheim: SINTEF, 2012).

S. Grådahl, H. Fardal, and I. Kero, Report No. F26839, Fugitive Dust Emissions at Wacker Holla (Trondheim: SINTEF, 2015).

S. Grådahl and H. Fardal, Report No. F26839, Fugitive Dust Emissions at ERAMET Sauda (Trondheim: SINTEF, 2013).

D.E. Evans, W.A. Heitbrink, T.J. Slavin, and T.M. Peters, Ann. Occup. Hyg. 52, 9 (2008).

K. Elihn and P. Berg, Ann. Occup. Hyg. mep033, 1 (2009).

H. Keskinen, S. Romakkaniemi, A. Jaatinen, P. Miettinen, E. Saukko, J. Jorma, J.M. Mäkelä, A. Virtanen, J.N. Smith, and A. Laaksonen, Aerosol Sci. Technol. 45, 1441 (2011).

H.D. Price, B. Stahlmecke, R. Arthur, H. Kaminski, J. Lindermann, E. Däuber, C. Asbach, T.A.J. Kuhlbusch, K.A. BéruBé, and T.P. Jones, J. Aerosol Sci. 76, 48 (2014).

J. Leskinen, J. Joutsensaari, J. Lyyränen, J. Koivisto, J. Ruusunen, M. Järvelä, T. Tuomi, K. Hämeri, A. Auvinen, and J. Jokiniemi, J. Nanopart. Res. 14, 1 (2012).

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by Norges Forskningsråd (NO) (Grant No. 237738). This article was enabled through funding from the Research Council of Norway through the center for research-driven innovation (SFI) Metal Production. The authors wish to thank Dr. Edin Myrhaug and Dr. Nils Eivind Kamfjord at Elkem AS for comments and discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11837-016-2202-9.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kero, I., Grådahl, S. & Tranell, G. Airborne Emissions from Si/FeSi Production. JOM 69, 365–380 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-016-2149-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-016-2149-x