Abstract

Soon after its introduction the mushroom speciesAgaricus bitorquis, which is immune to virus disease and prefers a warm climate, was threatened by the competitorDiehliomyces microsporus, false truffle. This fungus also likes warmth, and used to occur in crops ofA. bisporus.

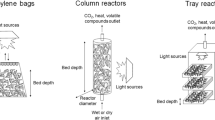

Mycelium and ascocarps were grown on several nutrient media. Optimum temperatures for mycelial growth were 26°C and 32°C, with a slight depression at 30°C. In trials in isolated growingrooms strain Somycel 2.017 ofA. bitorquis was generally used since it appeared to be highly sensitive to the competition of false truffle. Inoculation with mycelium, ascocarps or ascospores ofD. microsporus nearly always resulted in the presence of the competitor and in decreased mushroom yields. Even ten spores per m2 causedD. microsporus. The time of inoculation was most important: irrespective of the kind of inoculum, inoculation only resulted in both false truffle and yeild loss, if applied from spawning until a few days after casing. Inoculation at a later date could result in false truffle, but yield was not decreased.

As germination in vitro of ascospores failed, even after addition of various triggers, ascospore suspensions were treated at various temperatures for several periods. Then mushroom growing trays spawned with Somycel 2.017 were inoculated with the treated suspensions giving 7–11×107 spores/m2. The ascospores could not withstand 85°C for 0.5 h, 80°C for 1 h and 70°C for 3 h. Spontaneous incidence of false truffle, however, could not always be prevented and interfered with the results of these trials. It is possible that the thermal death-point of the ascospores is below 85°C. Fruiting bodies and ascospores did not survive ‘peak-heating’ at the beginning and cooking out (compost temperature 12 h at 70°C) at the end of a crop. After cooking out, however,D. microsporus could still be present in the wood of trays and contaminate a following crop if no wood preservative was applied.

Yield of Somycel 2.017 was reduced by the competition ofD. microsporus much more than yeilds of other strains ofA. bitorquis. The least sensitive were the highly productive strains Horst K26 and Horst K32.

The effects of fungicides onD. microsporus in vitro and in growing trials did not correspond. The fungicides tested so far could not prevent or controlD. microsporus. Growing of less sensitive strains ofA. bitorquis together with sanitary measures early in the crop and at the end of the crop, however, can prevent the competitor. failure to turn up of false truffle. To understand the discrepancy between the in vitro effects of several fungicides and their effect in inoculated mushroom trays, the rate of adsorption of benomyl in the substrate and probably the interrelationships between antagonists andD. microsporus require further research. Other strains ofA. bitorquis than Somycel 2.017 appeared to be less sensitive to the competition. Among these, highly productive strains Horst K26 and Horst K32 will not be hindered byD. microsporus if the following precautions are exercised: cooking out at the end of a crop (compost temperature 70°C for 12 hours), followed by treatment of the wood with SPCP; protection by hygiene early in the crop, i.e. covering of the compost by a thin plastic sheet during mycelial growth followed by a quick execution of casing.

Samenvatting

De teelt van de warmteminnende champignonsoortAgaricus bitorquis, die immuun is voor virusziekte, werd al spoedig na introductie bedreigd door de eveneens warmteminnende concurrentDiehliomyces microsporus, valse truffel. Deze schimmel kwam vroeger voor in teelten vanA. bisporus; de sporen zouden een temperatuur van 82°C gedurende 5 uur kunnen overleven (Lambert, 1932). Tabel 1 geeft de myceliumgroei op verschillende voedingsbodems en de vorming van vruchtlichamen (Fig. 1A, B) weer. De optimale temperaturen voor myceliumgroei waren 26°C en 32°C, met een licht depressie bij 30°C (Fig. 2). Proeven in geïsoleerde teeltruimten werden voornamelijk uitgevoerd met Somycel 2.017, een ras vanA. bitorquis. Inoculatie met mycelium, vruchtlichamen en/of ascosporen vanD. microsporus, al of niet in reincultuur gekweekt, leidde vrijwel steeds tot de aanwezigheid van de concurrent in de geïnoculeerde teeltkisten (Fig. 1C, D), waarbij vruchtlichamen met ascosporen (Fig. 1E) gevormd werden en tot een reductie van het aantal champignons. Tien sporen per m2 waren al voldoende omD. microsporus te doen aanslaan (Fig. 3). Het tijdstip van inoculatie bleek van groot belang te zijn: onafhankelijk van de aard van het inoculum leverde dit slechts zowel valse truffel als oogstreductie op, indien het werd aangebracht in de periode vanaf enten tot enkele dagen na het afdekken (Tabel 2 en Fig. 4). Inoculatie op latere tijdstippen kon wel tot valse truffel leiden, maar niet tot oogstreductie.

Aangezien de kieming van ascosporen in vitro slechte resultaten opleverede, ook na toevoeging van diverse stimulantia, werden ascosporensuspensies in vitro gedurende verschillende tijden bij verschillende temperaturen behandeld; vervolgens werden teeltkisten met de behandelde suspensies geïnoculeerd (7 tot 11×107 sporen/m2). De kisten waren tevoren geënt met Somycel 2.017. Een aantal proeven wees uit, dat de ascosporen 1/2 uur 85°C, 1 uur 80°C en 3 uur 70°C, niet overleefden (Tabel 3). Het spontaan optreden van valse truffel kon echter niet altijd worden voorkomen en beïnvloedde de uitkomsten van deze proeven. Daarom is het mogelijk, dat de sporen al bij een lagere temperatuur worden gedood Vruchtlichamen en ascosporen werden gedood door het ‘uitzweten’ aan het begin van een teelt en door het ‘doodstomen’ aan het einde van een teelt (composttemperatuur 12 uur 70°C) maar de schimmel bleek in het laatste geval wel over te kunnen blijven in het hout van teeltkisten als er vervolgens geen houtontsmettingsmiddel werd toegepast.

Somycel 2.017 leed verhoudingsgewijs meer schade door concurrentie vanD. microsporus dan enkele andere rassen (Tabel 4 en. 5). Inoculatie met ascosporen bleek bij de minst gevoelige en meest produktieve rassen Horst K26 en Horst K32 slechts te gelukken in extreem droge compost; bij Somycel 2.017 daarentegen zowel in compost met een laag als met een hoog vochtgehalte. Inoculatie met mycelium veroorzaakte meer valse truffel en meer schade naarmate de compost natter was (Tabel 5).

De werking van een aantal fungiciden in vitro (Tabel 6) en in teeltkisten (Tabel 7) stemde niet overeen. Aangezien de tot nu toe getoetste fungicidenD. microsporus niet kunnen voorkomen of bestrijden, moet preventie van deze concurrent worden gezocht in het telen van weinig gevoelige rassen vanA. bitorquis in combinatie met hygiënische maatregelen vroeg in en aan het eind van de teelt.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Baker, K. F. & Cook, R. J., 1974. Biological control of plant pathogens. W. H. Freeman Co., San Francisco, 433 pp.

Beach, W. S., 1937. Control of mushroom diseases and weed fungi. Bull. Penna agric. Exp. Stn 351, 32 pp.

Bels-Koning, H. C. & Bels, P. J., 1958. Handleiding voor de champignoncultuur. Proefstation voor de Champignoncultuur, Horst (L.), 295 pp.

Bollen, G. J. & Zaayen, A. van, 1975. Resistance to benzimidazole fungicides in pathogenic strains ofVerticillium fungicola. Neth. J. Pl. Path. 81: 157–167.

Diehl, W. W. & Lambert, E. B., 1930. A new truffle in beds of cultivated mushrooms. Mycologia 22: 223–226.

Dieleman-van Zaayen, A., 1972. Spread, prevention and control of mushroom virus disease. Mushr. Sci. 8: 131–154.

Emerson, M. R., 1948. Chemical activation of ascospore germination inNeurospora crassa. J. Bact. 55: 327–330.

Ferguson, M. C., 1902. A preliminary study of the germination of the spores ofAgaricus campestris and other Basidiomycetous fungi. Bull. Bur. Pl. Ind. U.S. Dep. Agric. (Washington) 16, 43 pp.

Fritsche, G., 1976. Welche Möglichkeiten eröffnet der viersporige ChampignonAgaricus bitorquis (Quél.). Sacc. dem Züchter? Theor. appl. Genet. 47: 125–131.

Fritsche, G. & Sengbusch, R. von, 1962. Die. züchterische Bearbeitung des Kulturchampignons (Psalliota bispora Lge.). Probleme und erste eigene Ergebnisse. Züchter 32: 189–199.

Gandy, D. G., Duncan, C. W. & Edwards, R. L., 1953. The use of copper sulphate for control of ‘truffle’ (Pseudobalsamia microspora). Mushr. Sci. 2: 167–174.

Gerrits, J. P. G., 1977. The supplementation of horse manure compost and synthetic compost with chicken manure and other nitrogen sources. Mushr. Sci. 9II, Taiwan: 77–98.

Gilkey, H. M., 1954. Taxonomic notes on Tuberales. Mycologia 46: 783–793.

Glasscock, H. H. & Ware, W. M., 1941. Investigations on the invasion of mushroom beds byPseudobalsmia microspora. Ann. appl. Biol. 28: 85–90.

Hasselbach, O. E. & Mutsers, P., 1971.Agaricus bitorquis (Quél.) Sacc. een warmteminnend familielid van de champignon. Champignoncultuur 15: 211–219.

Kligman, A. M., 1944. Control of the truffle in beds of the cultivated mushroom. Phytopathology 34: 376–384

Lambert, E. B., 1930. Two new diseases of cultivated mushrooms. Phytopathology 20: 917–919.

Lambert, E. B., 1932. The truffle disease of cultivated mushrooms. News Letter, Div. Mycol. and Dis. Sur. B.P.I., U.S. Dep. Agric. (neostyled), 4 pp.

Lambert, E. B. & Ayers, T. T., 1957. Thermal death times for some pests of cultivated mushroom (Agaricus campestris L.). Pl. Dis. Reptr 41: 348–353.

Olivier, J.-M., & Guillaumes, J., 1975. Trois nouvelles maladies dans les champignonnières françaises. Annls Phytopath. 7: 357–358.

Pompen, Th. G. M., 1975. De teeltwijze van K26 en K32. Champignoncultuur 19: 283–289.

Poppe, J. A., 1972. Un excellentAgaricus tétra-sporique cultivable commericalement avec succès. Mushr. Sci. 8: 517–525.

Sanderson, F. R., 1973. Benomyl for the control of false truffle. Mushr. J. 12: 546–547.

Schisler, L. C., Sinden, J. W. & Sigel, E. M., 1968. Etiology of mummy disease of cultivated mushrooms. Phytopathology 58: 944–948.

Stoller, B. B., 1962. Some practical aspects of making mushroom spawn. Mushr. Sci. 5: 170–184.

Sussman, A. S. & Halvorson, H. O. 1966. Spores. Their dormancy and germination. Harper & Row, New York, London, 354 pp.

Zaayen, A. van, 1976. Immunity of strains ofAgaricus bitorquis to mushroom virus disease. Neth. J. Pl. Path. 82: 121–131.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Van Zaayen, A., Van Der Pol-Luiten, B. Heat resistance, biology and prevention of Diehliomyces microsporus in crops of Agaricus species. Netherlands Journal of Plant Pathology 83, 221–240 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01977035

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01977035