Summary

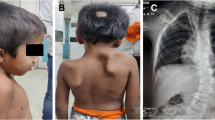

A five and a half weeks old female Kestrel exhibiting osteopathy of the pectoral and pelvic limbs, including symmetrical hyperdactyly, was investigated in order to clarify the pattern of the involved anatomical alterations and the possible causes of this developmental malformation. In the pectoral limb it consisted of a triplication of the alular digit, in the pelvic limb of a duplication of digit I. The live young Kestrel was observed for a period of two weeks to ascertain that it was unable to fly or procure prey on its own. After its death radiographs were taken and, apart from an eidonomic inspection including the wing claws, a detailed macroscopic dissection of the musculature of the pectoral and pelvic limbs was carried out using the ‘in-water-method’. Consecutive dissection steps were documented by a series of photographic slides. The relevant musculature, particularly that of the supernumerary digits, was recorded in proportional drawings. Subsequent to maceration of the limbs the isolated bones were reassembled according to the radiographs and also documented by means of photographs and drawings. This anatomical approach produced a reliable reconstruction of the skeletomuscular apparatus of the hyperdactylous limb parts. The eidonomic inspection revealed that at least young Kestrels may have two (alular and major digit) or even three wing claws per side. The proximal skeletal elements of both pectoral and pelvic limb were more sturdily built than in a typical Kestrel of comparable age. The proximal elements of the pelvic limb, the tarsometatarsus in particular, were shorter than in a typical Kestrel. In addition, the long axis of the tarsometatarsus was laterally bent in the transverse plane so that its proximal articular surfaces were medially inclined. Duplication of the cutaneous and osseous elements in the foot was accompanied by a duplication of some of the muscular and/or tendinous elements supplying digit I proper and the accessory digit I'. There were left-to-right asymmetries of the pedal musculature concerned. In contrast, the two accessory alular digits of each wing were almost completely devoid of musculature. Apart from atypical points of origin or insertion of the remaining distal musculture, left-to-right asymmetries and the two accessory alulae per wing, presumably, affected aerodynamic properties and resulted in flightlessness.

A juvenile Kestrel of similar age and without hyperdactyly was dissected for comparison. In addition, the external appearance of the carpometacarpal region of two female Silkies, an obligatory pentadactylous breed of domestic fowl, was inspected and the skeletal parts of their pectoral and pelvic limbs compared with those of the hyperdactylous Kestrel. Our results and a literature review suggest that the symmetrical hyperdactyly in the Kestrel bears striking similarities to the hereditary hyperdactyly observed in certain breeds of domestic fowl. In addition, there is a striking resemblance between the hyperdactyly of the young Kestrel and certain forms of hyperdactyly induced by molecular genetical experiments of other authors on chicks. Comparison with these results taken from the literature suggest that the symmetrical hyperdactyly in the young Kestrel, including the alterations of the proximal skeletal elements, is caused by an unusually early expression of the Hoxd-11 gene group during embryological development. Most likely, this gene group is situated on the 2nd chromosome in birds just as it is in mammals.

Zusammenfassung

Ein fünfeinhalb Wochen alter weiblicher Turmfalke mit einer Osteopathie der Vorder- und Hinterextremitäten, verbunden mit einer symmetrischen Hyperdactylie, wurde untersucht, um das Muster der beteiligten anatomischen Veränderungen und die möglichen Ursachen dieser Mißbildung zu erkennen. An der Vorderextremität bestand sie aus einer Verdreifachung des Alula-Fingers, an der Hinterextremität aus einer Verdoppelung der Zehe I. Die Beobachtung des lebenden jungen Turmfalken während eines Zeitraumes von zwei Wochen ergab, dass er flugunfähig war und keine Beute schlagen konnte.

Nach seinem Tod und einer Inspektion der Eidonomie, einschließlich der Flügelkrallen, wurden Röntgenaufnahmen angefertigt. Danach folgte eine detaillierte makroskopische Präparation der Flügel- und Beinmuskulatur unter Verwendung der „In-Wasser-Methode“. Die einzelnen Präparationsschritte wurden anhand von Dia-Serien dokumentiert. Die relevante Muskulatur, insbesondere die der überzähligen Digiti, wurde in proportionsgetreuen Zeichnungen festgehalten. Nach Mazeration der Extremitäten wurden die Einzelknochen, entsprechend den Röntgenbildern, wieder zusammengesetzt und ebenfalls mit Fotografien und Zeichnungen dokumentiert. Dieser anatomische Ansatz lieferte eine zuverlässige Rekonstruktion des Skelett-Muskel-Apparates der hyperdactylen Extremitätenanteile.

Die eidonomische Inspektion ergab, dass zumindest junge Turmfalken zwei (Digitus alularis und majoris) oder sogar drei Flügelkrallen haben können. Die proximalen Skelettelemente der Vorder- und Hinterextremität waren deutlich robuster gebaut als bei einem typischen Turmfalken vergleichbaren Alters. Die proximalen Elemente der Hinterextremität, insbesondere der Tarsometatarsus, waren kürzer als bei einem typischen Turmfalken. Darüberhinaus war die Längsachse des Tarsometatarsus in der Transversalebene laterad gekrümmt, so dass sich seine proximalen Gelenkflächen schräg mediad richteten. Entsprechend der kutanen und knöchernen Doppelbildungen des Fußes waren auch einige der Muskeln und Sehnen doppelt vorhanden, welche die eigentliche erste Zehe und die akzessorische erste Zehe versorgten. Es traten Rechts-/Links-Asymmetrien der betreffenden Muskulatur auf. Im Gegensatz dazu waren die beiden akzessorischen Alula-Finger jedes Flügels fast vollständig ohne Muskulatur. Abgesehen von atypischen Ursprungs- und Insertionspunkten der verbleibenden distalen Muskulatur, beeinträchtigten Rechts-/Links-Asymmetrien und die beiden akzessorischen Alulae pro Flügel vermutlich die aerodynamischen Eigenschaften und führten zur Flugunfähigkeit.

Ein junger Turmfalke ähnlichen Alters ohne Hyperdactylie wurde zum Vergleich präpariert. Zusätzlich wurde die äußere Erscheinung der Carpometacarpal-Region zweier Seidenhühner, einer obligatorisch pentadactylen Hühnerrasse, inspiziert und die Skelettelemente ihrer Vorder- und Hinterextremitäten mit denen des hyperdactylen Turmfalken verglichen. Unsere Ergebnisse und ein Überblick der Literatur lassen auffallende Übereinstimmungen zwischen der symmetrischen Hyperdactylie des jungen Turmfalken und der erblichen Hyperdactylie bestimmter Hühnerrassen erkennen. Darüberhinaus besteht eine auffallende übereinstimmung zwischen der Hyperdactylie des jungen Turmfalken und bestimmten Formen der Hyperdactylie, welche von anderen Autoren durch molekulargenetische Experimente an Hühnerküken induziert wurden. Ein Vergleich mit diesen Ergebnissen aus der Literatur legt nahe, dass die symmetrische Hyperdactylie des jungen Turmfalken, einschließlich der Veränderungen der proximalen Skelettelemente, durch eine ungewöhnlich frühe Expression der Hoxd-11 Gengruppe im Laufe der Embryonalentwicklung verursacht wurde. Sehr wahrscheinlich ist diese Gengruppe bei Vögeln auf dem zweiten Chromosom lokalisiert — ebenso wie bei Säugetieren.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anthony, R. (1899): Étude sur la polydactylie chez les Gallinacés. J. Anat. Physiol., Paris 35: 711–750.

Ballowitz, E. (1904): Welchen Aufschluß geben Bau und Anordnung der Weichteile hyperdactyler Gliedmaßen über die Ätiologie und die morphologische Bedeutung der Hyperdactylie des Menschen? Virch. Arch. Path. Anat. Physiol. 178: 1–25.

Barfurth, D. (1908): Experimentelle Untersuchung über die Vererbung der Hyperdactylie bei Hühnern. 1. Mitteilung: Der Einfluß der Mutter. Arch. Entw.-Mech. 26: 631–650.

Barfurth, D. (1911a): —. 3. Mitteilung: Kontrollversuche und Versuche am Landhuhn. Arch. Entw.-Mech. 31: 479–511.

Barfurth, D. (1911b): Die Hyperdactylie des Fusses und des Flügels beim Houdanhühnchen. Sitz. Ber. Abh. Naturforsch. Ges. Rostock 3 (N. F.): 20–24.

Barfurth, D. (1912): —. 4. Mitteilung: Der Flügelhöcker des Hühnchens, eine rudimentäre Hyperdactylie. Arch. Entw.-Mech. 33: 255–273.

Barfurth, D. (1914): —. 5. Mitteilung: Weitere Ergebnisse und Versuch ihrer Deutung nach den Mendelschen Regeln. Arch. Entw.-Mech. 40: 279–309.

Bateson, W. (1894): Materials for the study of variation. London.

Baumel, J. J., King, A. S., Lucas, A. M., Breazile, J. E. & Evans, H. E. (1979): Nomina anatomica avium. London.

Beebe, C. W. (1910): Three cases of a supernumerary toe in the broad-winged hawk (Buteo brachypterus). Zoologica 1: 150–152.

Bitgood, J. J. & Somes, R. G. (1990): Linkage relationships and gene mapping. In: R. D. Crawford (Ed.): Poultry breeding and genetics: 469–495. Amsterdam.

Boas, J. E. V. (1884): Bidrag til Opfattelsen af Polydactyli hos Pattedyrene. Vidensk. Med. Naturhist. Foren. Kjøbenhavn 1883: 1–16.

Braus, H. (1908): Entwicklungsgeschichtliche Analyse der Hyperdactylie. Muenchn. Med. Wschr. 55: 386–390.

Bretscher, A. (1950): Experimentelle Unterdrückung der Polydactylie beim Hühnchen. Rev. suisse Zool. 57: 576–583.

Brickell, P. M. & Tickle, C. (1989): Morphogens in chick limb development. BioEssays 11: 145–149.

Coale, H. K. (1887): Ornithological curiosities. — A hawk with nine toes, and a bobolink with spurs on its wings. Auk 4: 231–233.

Cohn, M. J. & Bright, P. E. (1999): Molecular control of vertebrate limb development, evolution and congenital malformations. Cell Tissue Res. 296: 3–17.

Columella, L. I. M. (1982): De re rustica. Libri duodecim. Incerti auctoris liber de arboribus, lat.-dt. vol. II, liber octavus: 228–329. München.

Cooper, J. E. (1984): Developmental abnormalities in two British falcons (Falco spp.). Avian Pathol. 13: 639–645.

Cowper, J. (1886): On the pentadactylous pes in the Dorking fowl, a variety of theGallus domesticus, with especial reference to the hallux. J. Anat. Physiol. 20: 593–595.

Cowper, J. (1889): On hexadactylism, with especial reference to the signification of its occurrence in a variety of theGallus domesticus. J. Anat. Physiol. 23: 242–249.

Davenport, C. B. (1906): Inheritance in poultry. Publ. Carnegie Institut. Washington No. 52: 136 pp.

Dei, A. (1890): Considerazioni sulla Iperdattilia o Pentadattilia nei gallinacci domestici. Atti R. Accad. Fis. ser. IV 2: 471–494.

Dons, C. (1928): En fugl med 4 føtter. Kongel. Norske Vidensk. Selsk. Forh. 1: 73–74.

Duboule, D. (1991): Patterning in the vertebrate limb. Current opinion in genetics and development 1: 211–216.

Duboule, D. (1994): Guidebook to the homeobox genes. Oxford.

Dunn, L. C. & Jull, M. A. (1928): On the inheritance of some characters of the silky fowl. J. Genetics 29: 27–63.

Esther, H. (1937): Ein seltener Fall von Hyperdactylie beim Turmfalken,Falco t. tinnunculus L. Mitt. Ver. sächs. Orn. 5: 111–115.

Fisher, H. I. (1940): The occurrence of vestigial claws on the wings of birds. Am. Midl. Nat. 23: 234–243.

Fogarty, M. J. (1969): Extra toes on the halluces of a Common Snipe. Auk 86: 132.

Fox, N. C. (1989): A unilateral extra digit in a wild common buzzard (Buteo buteo). Avian Pathol. 18: 193–196.

Ghigi, A. (1901): Sul significato morfologico della polidattilia nei Gallinacei. Ric. Lab. Anat. Norm., Roma 8: 139–148.

Gloor, H. (1946): Eine seltene Mißbildung bei einem Vogel (Chloris chloris L.). Rev. suisse Zool. 53: 442–446.

Grönberg, G. (1894): Beiträge zur Kenntnis der polydactylen Hühnerrassen. Anat. Anz. 9: 509–516.

Herre, W. & Röhrs, M. (1990): Haustiere — zoologisch gesehen. Stuttgart.

Hillel, E. (1904): Ueber die Vorderextremität vonEudyptes chrysocome und deren Entwicklung. Jen. Z. Naturwiss. 38 (N. F. 31): 725–770.

Howes, G. B. & Hill, J.P. (1892): On the pedal skeleton of the Dorking fowl, with remarks on hexadactylism and phalangeal variation in the amniota. J. Anat. Physiol. 26: 395–403.

Jäckel, A. J. (1874): Ueber Monstrositäten wilder Vögel. Zool. Garten, Frankfurt 15: 441–446.

Jeffries, A. (1883): On the claws and spurs on birds' wings. Proc. Boston Soc. Nat. Hist. 21: 301–306.

Johnson, R. L. & Tabin, C. J. (1997): Molecular models for vertebrate limb development. Cell 90: 979–990.

Kaufmann-Wolf, M. (1908): Embryologische und anatomische Beiträge zur Hyperdactylie (Houdanhuhn). Morph. Jb. 38: 471–531.

Kummerloeve, H. (1952): Ein weiterer Fall von Hyperdactylie bei einem Tagraubvogel. Beitr. Vogelkd. 2: 102–108.

Langkavel, B. (1886): Hühner mit sechs Zehen (Kurznotiz). Zool. Garten, Frankfurt 27: 35.

Lönnberg, E. (1907): Egendomlig dubbelmissbildning hos sparfhök (Eigentümliche Doppelmißbildung beim Sperber). Fauna och Flora 2: 212–213.

Macias, D., Gañan, Y., Rodriguez-Leon, J., Merino, R. & Hurle J. M., (1999): Regulation by members of the transforming growth factor beta super-family of the digital and interdigital fates of the autopodial limb mesoderm. Cell Tissue Res. 296: 95–102.

Marks, H. & Krebs, W. (1968): Unser Rassegeflügel — Hühner, Enten, Gänse, Puten, Perlhühner. Berlin.

Matthiass, K. (1912): Die Varianten der Hyperdactylie beim Huhn. Sitz. Ber. Abh. Naturforsch. Ges. Rostock (N. F.) 3: 1–32.

Morgan, B. A., Izpisúa-Belmonte, J. C., Duboule, D. & Tabin, C. J. (1992): Targeted misexpression of Hox-4.6 in the avian limb bud causes apparent homeotic transformations. Nature 358: 236–239.

Morgan, B. A. & Tabin, C. (1994): Hox genes and growth: early and late roles in limb bud morphogenesis. Development 1994, Suppl.: 181–186.

Muragaki, Y., Mundlos, S., Upton, J. & Olsen B. R., (1996): Altered growth and branching patterns in synpolydactyly caused by mutations in HOXD13. Science 272: 548–551.

Nickel, R., Schummer, A. & Seiferle, E. (1992): Lehrbuch der Anatomie der Haustiere, Bd. 5: Anatomie der Vögel. Berlin.

Norsa, E. (1894): Recherches sur la morphologie des membres antérieurs des oiseaux. Arch. Ital. Biol. 22: 232–241.

Pätzold, W. (1984): Überzählige Zehen bei einer Lachmöve,Larus ridibundus. Beitr. Vogelk. 30: 209.

Punnet, R. C. & Pease, M. S. (1929): Genetic studies in poultry. VII. Notes on polydactyly. J. Genetics 21: 341–366.

v. Reichenau, W. (1880): Ein fünfzehiger Raubvogel. Kosmos 7: 318–319.

Riddle, R. D., Johnson, R.L., Laufer, E. & Tabin, C. (1993): Sonic hedgehog mediates the polarizing activity of the ZPA. Cell 75: 1401–1416.

Riddle, R. D. & Tabin, C. J. (1999): Wie Arme und Beine entstehen. Spektrum der Wissenschaft, September 1999: 62–68.

Saunders, J. W. (1948): The proximo-distal sequence of origin of the parts of the chick wing and the role of the ectoderm. J. Exp. Zool. 108: 363–403.

Simon, H.-G. (1999): T-box genes and the formation of vertebrate forelimb- and hindlimb specific pattern. Cell Tissue Res. 296: 57–66.

Somes, R. G. (1988): International registry of poultry genetic stocks. Document Number Bulletin 476. University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Somes, R. G. (1990): Mutations and major variants of muscles and skeleton in chickens. In: R. D. Crawford (Ed.): Poultry breeding and genetics: 209–237. Amsterdam.

Steinbacher, J. (1957): Doppelfuß bei einem Eichelhäher. Natur und Volk 87: 328–331.

Steinbacher, J. (1958): Zur Anatomie der Diplopodie bei einem Vogel. Senck. biol. 39: 41–45.

Steiner, H. (1922): Die ontogenetische und phylogenetische Entwicklung des Vogelflügelskelettes. Acta Zool. 3: 307–360.

Stephan, B. (1992): Vorkommen und Ausbildung der Fingerkrallen bei rezenten Vögeln. J. Ornithol. 133: 251–277.

Stephan, B. (1997): Reduktion von Fingerkrallen, Phalangen und Handschwingen. Mitt. Zool. Mus. Berl. 73, Suppl. Ann. Orn. 21: 45–57.

Stevens, L. (1991): Genetics and evolution of the domestic fowl. Cambridge.

Stresemann, E. (1927–34): Aves. In: W. Kükenthal (Ed.). Handbuch der Zoologie 7/2. Berlin.

Sudhaus, W. (1981): Problembereiche der Homologienforschung (General problems of homologizing). Verh. Dtsch. Zool. Ges. 1980: 177–187.

Sudilowskaja, A. M. (1958): Cases of polypody and polydactyly in birds (in Russian). Ornitologija 1: 207–214.

Trinkaus, K., Müller, F. & Kaleta, E. F. (1999): Polydactylie bei einem Turmfalken (Falco tinnunculus tinnunculus Linné, 1758) — ein Fallbericht. Z. Jagdwiss. 45: 66–72.

Vedder, O. (2000): TorenvalkFalco tinnunculus met vleugelafwijking. De Takkeling 8: 140–141.

Vollmerhaus, B. (1992): Spezielle Anatomie des Bewegungsapparats. In: R. Nickel, A. Schummer & E. Seiferle (Eds.): Anatomie der Vögel: 54–154. Berlin.

Warren, D. C. (1941): A new type of polydactyly in the fowl. J. Heredity 32: 1–5.

Warren, D. C. (1944): Inheritance of polydactylism in the fowl. Genetics 29: 217–231.

Yokouchi, Y., Ohsugi, K., Sasaki, H. & Kuroiwa, A. (1991): Chicken homeobox gene Msx-1: structure, expression in limb buds and effect of retinoic acid. Development 113: 431–444.

Zákány, J., Fromental-Ramain, C., Warot, X. & Duboule, D. (1997): Regulation of number and size of digits by posterior Hox genes: a dose-dependent mechanism with potential evolutionary implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 13695–13700.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frey, R., Albert, R., Krone, O. et al. Osteopathy of the pectoral and pelvic limbs including pentadactyly in a young Kestrel (Falco t. tinnunculus). J Ornithol 142, 335–366 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01651372

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01651372