Abstract

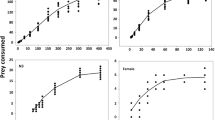

When juvenile praying mantids (Tenodera sinensis)were exposed to unpalatable prey (the milkweed bug Oncopeltus fasciatus),they attacked, sampled, and then usually rejected the prey. About 70% of the handling time was spent feeding. When offered a second milkweed bug, the mantids usually attacked the prey. However, the overall time required for the mantids to sample, recognize, and then reject the unpalatable prey decreased by half. The proportion of handling time that was spent feeding remained the same as in the first encounter. In contrast, when the second prey individuals encountered by mantids were Drosophila melanogaster,the flies were completely consumed and the proportion of handling time that was spent feeding significantly increased. When praying mantids were exposed to the milkweed bugs for the first time, up to 33% of the bugs survived attack by the mantids. Survival of milkweed bugs increased to 55% when mantids had been previously exposed to the bugs. In contrast, flies that were caught never survived.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Berenbaum, M., and Miliczky, E. (1984). Mantids and milkweed bugs: Efficacy of aposematic coloration against invertebrate predators.Am. Midl. Natur. 111: 64–68.

Duffey, S. S., Blum, M. S., Isman, M. B., Scudder, G. G. E. (1978). Cardiac glycosides: A physical system for their sequestration by the milkweed bug.J. Insect Physiol. 24: 639–645.

Elner, R. W., and Hughes, R. N. (1978). Energy maximization in the diet of the shore crab,Carcinus maenus.J. Anim. Ecol. 47: 103–116.

Erichsen, J. T., Krebs, J. R., and Houston, A. I. (1980). Optimal foraging and cryptic prey.J. Anim. Ecol. 49: 271–276.

Ferguson, J. E., and Metcalf, R. L. (1985). Cucurbitacins: Plant-derived defense compounds for diabroticites (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae).J. Chem. Ecol. 11: 311–318.

Gelperin, A. (1968). Feeding behavior of the praying mantis: A learned modification.Nature 286: 149–150.

Houston, A. I., Krebs, J. R., and Erichsen, J. T. (1980). Optimal prey choice and discrimination time in the great tit (Parus major L.).Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 6: 169–175.

Hughes, R. N. (1979). Optimal diets under the energy maximization premise: The effects of recognition time and learning.Am. Nat. 113: 209–221.

Jarvi, T., Sillen-Tullberg, B., and Wiklund, C. (1981). The cost of being aposematic. An experimental study of predation on larvae ofPapilio machaon by the great titParus major.Oikos 36: 267–272.

Krebs, J. R. (1978). Optimal foraging: Decision rules for predators. In Krebs, J. R., and Davies, N. B. (ed.),Behavioural Ecology: An Evolutionary Approach, Blackwell, Oxford, pp. 23–63.

Krebs, J. R., Kaceinik, A., and Taylor, P. (1978). Test of optimal sampling by foraging great tits.Nature 275: 27–31.

Paradise, C. J., and Stamp, N. E. (1990). Variable quantities of toxic diet cause different degrees of compensatory and inhibitory responses by juvenile praying mantids.Entomol. Exp. Appl. 55: 213–222.

Paradise, C. J., and Stamp, N. E. (1991). Abundant prey can alleviate previous adverse effects on growth of juvenile praying mantids (Mantidae).Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. (in press).

Pyke, G. H. (1984). Optimal foraging theory: A critical review.Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 15: 523–575.

Ralph, C. P. (1976). Natural food requirements of the large milkweed bugOncopeltus fasciatus (Hemiptera: Lygaeidae) in their relation to gregariousness and host plant morphology.Oecologia 26: 157–176.

Rilling, S., Mittelstaedt, H., and Roeder, K. D. (1959). Prey recognition in the praying mantis.Behaviour 14: 164–184.

Schoener, T. W. (1971). Theory of feeding strategies.Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 11: 369–404.

Sillen-Tullberg, B. (1985). Higher survival of an aposematic than of a cryptic form of a distasteful bug.Oecologia 67: 411–415.

Sokal, R. R., and Rohlf, F. J. (1981).Biometry, 2nd ed. W. H. Freeman, New York.

Stephens, D. W., and Krebs, J. R. (1986).Foraging Theory, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Wiklund, C., and Jarvi, T. (1982). Survival of distasteful insects after being attacked by naive birds: A reappraisal of the theory of aposematic coloration evolving through individual selection.Evolution 36: 998–1002.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paradise, C.J., Stamp, N.E. Prey recognition time of praying mantids (Dictyoptera: Mantidae) and consequent survivorship of unpalatable prey (Hemiptera: Lygaeidae). J Insect Behav 4, 265–273 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01048277

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01048277