Abstract

Hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine is a prescription opioid licensed in the USA for the relief of cough and upper respiratory symptoms associated with allergy or cold in adults, previously contraindicated in children aged < 6 years. We present findings from a modern benefit risk review of hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine use as an antitussive agent in patients aged 6 to < 18 years. A cumulative search of the manufacturer’s pharmacovigilance database covering 1 January 1900–7 August 2017 identified all individual case safety reports (ICSRs) associated with product family name “hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine.” The search was inclusive of all MedDRA system organ classes, stratified by age (< 18 years). A comprehensive review of the scientific literature was conducted on safety and efficacy of opioids for pediatric treatment of cough. Three hundred and ninety-one ICSRs associated with hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine were identified; 35/391 ICSRs were in patients < 18 years of age; 18 were considered serious. Four fatalities were reported in patients 6 to < 18 years; two fatalities involved co-suspect medication azithromycin and two were poorly documented. Our literature search identified no robust efficacy data for hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine in the relief of cough and upper respiratory symptoms associated with allergy or cold in patients aged 6 to < 18 years. As we found no evidence of hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine efficacy in the pediatric population, we conclude that the benefit risk profile is unfavorable. This evidence contributed to the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) recent decision that hydrocodone-containing cough and cold medications should no longer be indicated for treatment of cough in patients < 18 years, highlighting the value of proactive re-evaluation of the benefit risk profile of older established drugs.

Plain Language Summary

People often use medicines containing opioids to treat cough symptoms. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently decided that cough medicines containing opioids should not be used by children under 18 years old. Part of this decision was a review of the benefits and risks of using cough medicines that contain the opioid hydrocodone in children.

Why was this review carried out? Most cough medicines that doctors can prescribe were approved several decades ago. Since then, rules for the approval of medicines have become stricter. In this review, researchers looked at the safety of hydrocodone, and how well this opioid relieves cough symptoms in children. Up-to-date information and modern research methods were used.

The two key pieces of evidence found were:

-

We could not locate any clinical trials providing robust evidence for the use of hydrocodone for cough relief in children under 18 years of age. (Outside the scope of this review, a number of clinical trials of hydrocodone-containing cough medicines in adults aged 18 years and over have shown the medicine to be effective in these patients.)

-

Cough medicines containing opioids can cause harmful side effects in children such as breathing problems. In the research reported here, ten children died after taking a hydrocodone-containing cough medicine. Nine of these deaths were due to overdose.

This evidence was used to draw the following conclusions:

-

In children under 18 years of age, the risks of using hydrocodone for cough relief are greater than any benefits.

-

Older medicines should be reviewed regularly to look at their safety and how well they are working using up-to-date evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The potential risks associated with the prescription opioid cough and cold medication hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine in patients < 18 years of age outweigh the benefits. |

Conclusions from this benefit risk assessment have contributed to a decision by the FDA to limit the use of hydrocodone-containing cough and cold medications to patients aged ≥ 18 years of age. |

This review highlights the need to continually re-evaluate the safety and efficacy of older, established drugs using up to date clinical evidence and modern methods. |

1 Introduction

The escalation of therapeutic opioid use is a key concern in modern medicine and public health [1, 2]. The supply of opioids in the USA increased from the equivalent of 96 mg of morphine per person in 1997 to 710 mg in 2010 [1, 3]. This has been accompanied by a corresponding increase in fatalities and other adverse events (AEs). In the USA, the death rate from prescription opioids increased from 6.1 per 100,000 population in 2009 to 13.8 per 100,000 population in 2013, and between 2006 and 2012, almost 22,000 pediatric patients were treated for opioid poisoning in US emergency departments [4].

Hydrocodone is one such prescription opioid following this trend, prescriptions of which increased by 280% between 1997 and 2007 [5]. This semisynthetic narcotic analgesic has multiple actions, qualitatively similar to those of codeine [6, 7]. In October 2014, hydrocodone-containing antitussive agents were reclassified from schedule III to schedule II drugs by the US Drug Enforcement Administration in recognition of their high potential for drug abuse [8].

In January 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced an update to the safety labelling of prescription opioid cough and cold medications. Consequently, manufacturers of cough and cold medications containing codeine or hydrocodone will be required to update the labeling with a “Boxed Warning” explaining the risks of opioid misuse, abuse, addiction, overdose, death, and breathing difficulties. The FDA also made the decision to limit the use of these medications to patients aged ≥ 18 years, stating “these products will no longer be indicated for use to treat cough in any pediatric population” [9, 10]. One medication affected by this safety update is Tussionex® Pennkinetic® (hydrocodone polistirex/chlorpheniramine polistirex). Each 5-ml dose of this extended-release suspension contains hydrocodone polistirex equivalent to 10 mg hydrocodone bitartrate, plus the antihistamine chlorpheniramine polistirex, equivalent to 8 mg chlorpheniramine maleate [11].

Tussionex® Pennkinetic® was first filed as a new drug application in 1983 after the first hydrocodone product, Hycodan®, was found to be effective for the symptomatic relief of cough during the FDA’s Drug Efficacy Study Implementation (DESI) review [12]. The 1962 DESI program required that all drug products approved in the USA between 1938 and 1962 be reviewed for effectiveness, whereas previous approval was based solely on demonstrating safety [13]. During this process the FDA took action on 3443 products, 2225 of which were found to be effective based on existing evidence at the time [14].

Tussionex® Pennkinetic® was licensed for use in adults and children in 1987 for the symptomatic relief of cough and upper respiratory symptoms associated with cold and allergies. In May 2007, due to safety concerns and reports of a number of serious adverse events (SAEs) in children < 6 years of age, including a number of fatalities, the manufacturer submitted a “changes being effected” (CBE) labeling supplement (S-015) to the FDA [15, 16]. This included a contraindication in children < 6 years of age and a recommendation to use a more accurate measuring device to reduce the risk of overdose. The FDA also responded to these safety concerns, releasing a public health alert on the correct use of the drug in 2008 [17]. To address concerns around overdosing, in October 2011 the manufacturer launched a unit of use package (115 ml deliverable volume), which included a dosing device validated to allow for accurate dosing, and at the same time the 473-ml bottle was discontinued.

Traditional pharmacovigilance analysis, based upon regulatory guidance, involves review of the safety database, data from the health authority database and the literature. Here, we present findings from a modern pharmacovigilance analysis that includes thorough and comprehensive review of the available safety and efficacy data for hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine use in pediatric patients between 6 and < 18 years of age, current standards of care in clinical practice, previous FDA advisory board meeting minutes and real-world evidence. The results were used as supporting evidence for the FDA’s decision to update the safety labeling for opioid-containing prescription cough and cold medication [10].

2 Methods

2.1 Estimated Patient Exposure to Hydrocodone/Chlorpheniramine

The total exposure to hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine during the period of 1 January 2007 to 31 July 2017 was estimated based on the manufacturer’s sales data; 1 January 2007 was the earliest time point at which sales data could be extracted.

In line with the Summary of Product Characteristics, the standard daily dose (SDD) for hydrocodone was assumed to be 20 mg [11]. Patient years (PY) of exposure were calculated using the following formula:

2.2 Review of the Sponsor Safety Database

The manufacturer’s global safety database provides spontaneous and solicited AE reports from worldwide sources (including healthcare professionals [HCPs], consumers, non-interventional studies and the literature) for all manufacturer marketed products, as well as SAE reports from clinical trials of any compounds in development. A cumulative search of the database covering the period from 1 January 1900 (in line with the manufacturer’s patient safety search conventions) to 7 August 2017 was conducted for all individual case safety reports (ICSRs). The search was performed by product family name “hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine” and was inclusive of all MedDRA system organ classes, then further stratified by age (< 18 years).

2.3 Literature Review to Examine Safety and Effectiveness of Opioid Antitussive Treatments

A comprehensive literature review assessed the evidence relating to the safety and effectiveness of opioid use for cough and cold in pediatrics, covering the period of 19 March 2015–8 June 2016. Literature sources included, but were not limited to: the manufacturer’s review of safety data, medical literature such as a 2012 review of studies of cough medications in children [18], the 2015 joint meeting of the Pediatric and Drug Safety Advisory Committees [19], the 2015 European Medicines Agency (EMA) review [20], the American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical Report [21], and epidemiological (prescription) data (see Table 1 for a complete list of sources used).

3 Results

3.1 Patient Exposure to Hydrocodone/Chlorpheniramine

Between 1 January 2007 and 31 July 2017, total exposure to hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine for patients < 18 years was estimated to be 673,487 PY; exposure was highest in 2008, followed by an overall decline through to 2017 (Fig. 1).

Patient years of exposure to hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine per fiscal year from 1 January 2007–31 July 2017. The manufacturer’s sales data were used to estimate annual exposure to hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine. aData available from 1 January 2017–31 July 2017. PY patient years. Exposure is based on a standard daily dose of 20 mg used in adults; the actual daily dose in pediatric patients is likely to have been lower, resulting in higher annual exposure rates than presented

3.2 Cumulative Review of Pediatric Safety Data from the Sponsor Safety Database

A cumulative review of the manufacturer’s global safety database identified 391 ICSRs associated with the hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine combination product since 1 January 1990. Of these, 35 ICSRs (9%) were in pediatric patients < 18 years of age. Most cases, 24/35 ICSRs (66.7%), described use in pediatric patients < 6 years of age. Trend analysis of annual ICSR reporting rates between 1 January 2007 and 31 July 2017 showed 2009 had the highest reporting rate at 5.67 cases/100,000 PY (Fig. 2). No pediatric cases were identified in the global safety database after 1 January 2011.

Trend analysis of annual reporting rates for pediatric cases from 1 January 2007–31 July 2017. ICSRs were analyzed by trend analysis to calculate reporting rate for pediatric cases/100,000 PY. aData available from 1 January 2017–31 July 2017. ICSR individual case safety report, PY patient years. Exposure is based on a standard daily dose of 20 mg used in adults; the actual daily dose in pediatric patients is likely to have been lower, resulting in higher annual exposure rates than presented

Overall, 18/35 of the pediatric ICSRs were considered serious. Of these, ten were fatal (Fig. 3), with nine fatalities attributed to overdose or error in drug prescribing by a HCP and/or administration by a family member (Table 2). One fatality, involving a 4-year-old patient, occurred after the < 6 years contraindication was implemented, and two fatalities involved co-suspect medication azithromycin (Table 2), a known CYP450 substrate able to disrupt hydrocodone metabolism, potentially resulting in the accumulation of hydrocodone to toxic levels [22].

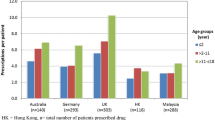

Number of individual case safety reports associated with hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine treatment by seriousness in pediatric patients < 18 years from 1 January 1900–7 August 2017. Number of ICSRs per age group are reported according to whether the AE was considered serious and fatal, serious but not fatal, or non-serious. AE adverse event, ICSR individual case safety report

The remaining eight serious ICSRs were non-fatal (Fig. 3), with hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine medication prescribed by a HCP. Of these, five cases involved patients < 6 years of age, all of which occurred prior to the contraindication in this age group and described respiratory depression and/or breathing difficulties. The other three serious cases were reported in patients aged 6 to 17 years, of which two were classified as hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine overdose. There were no reported events of respiratory depression/breathing problems in these three cases, which were either poorly documented or implied other risk factors in the patients’ medical history for the reported events.

Of the 35 ICSRs reported for pediatric patients, 17 were non-serious (Fig. 3). Twelve of these cases involved patients < 6 years of age, nine of which described prescribing or medication error without any associated clinical AEs reported. Three of the 12 cases described events which were listed AEs (such as sedation and somnolence) as per the United States Prescribing Information (USPI) or involved use of other concomitant medication such that causality due to hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine could not be confirmed. The three non-serious ICSRs described in pediatric patients ≥ 6 years were all in patients aged 9 to 16 years and were poorly documented. Two cases lacked details such as time to onset or medical history, and one case described drug prescribing error (wrong dose) with no associated clinical events. The two remaining non-serious ICSRs involved pediatric patients of unknown age, where one case was again poorly documented for the reported events and the other described medication error (reported as “giving child an adult dose”) with no associated clinical events.

Further analysis of the 24 ICSRs reported in patients < 6 years revealed a total of 56 AEs, with some patients experiencing more than one AE. For patients aged 6 to 17 years, a total of 47 AEs were reported in the ICSRs (Table 3). Two AEs, one case each of medication error and movement disorder, were reported in pediatric patients of unknown age.

3.3 Efficacy and Safety of Opioid Antitussive Treatment in Pediatric Populations in the Literature

A targeted review of the literature identified no reports of efficacy data for hydrocodone for the relief of cough and upper respiratory symptoms associated with allergy or a cold within the 6 to < 18 years subpopulation; the literature indicates that cough and cold in pediatric patients should ideally be managed by treatment of the underlying disorder rather than the symptoms [23]. Furthermore, the evidence identified regarding the safety of hydrocodone in the 6 to < 18 years patient population was inconclusive. For example, post-operative use of codeine and hydrocodone in 6- to 17-year-old patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome has been found to increase oxygen desaturation, compromising respiratory drive [24], whilst a study investigating post-operative use of a hydrocodone/acetaminophen combination product in the same age group reported no deaths or significant AEs associated with the study drug [25].

4 Discussion

Prescription opioid use and abuse has led to major concerns among the US medical community, government officials and the general public, and is considered a serious public health issue [1,2,3]. Tussionex® Pennkinetic® is a prescription combination product containing the opioid hydrocodone in addition to chlorpheniramine. Here, we report results from a modern pharmacovigilance review of the benefit risk profile of hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine within patients aged 6 to < 18 years. Findings from this review were used to support a recent update to the labelling of opioid-containing cough and cold medications such that these products will no longer be indicated for use in any patient < 18 years of age [9].

Between 2007 and 2017, the peak reporting rate for pediatric ICSRs relating to hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine was in 2009. From 2011 onwards no ICSRs were reported within the manufacturer’s global safety database. This decline in reporting rates coincides with the 2008 labeling supplement and 2011 introduction of unit of use packaging by the manufacturer, both of which may have contributed to the absence of pediatric ICSRs since 2011.

Our review of all available safety data for hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine use in pediatric patients confirms that the contraindication for children < 6 years remains appropriate due to the susceptibility of this population to life-threatening and fatal respiratory depression. Overall, the data identified in both the literature and the sponsor safety database for the pediatric population aged 6 to < 18 years were less conclusive. This age group accounted for 39% of all pediatric SAEs recorded in the global safety database, and 18% of the non-serious AEs. However, many of the ICSRs identified were poorly documented such that causality with hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine could not be confirmed.

Alongside the safety risks, there is now evidence to suggest a possible association between legitimate opioid prescribing for pediatric patients ≤ 18 years and misuse in later years [26, 27]. In particular, a US study found that individuals prescribed an opioid medication for a legitimate indication by age 17 to 18 years were on average 33% more likely to misuse prescription opioids by age 23 years than those with no history of opioid prescription [28]. This evidence is from observational, population-based studies, and as such no specific causal relationship can be proven or inferred. However, these findings should be considered when prescribing opioid products to pediatric patients.

The efficacy of hydrocodone and chlorpheniramine in the treatment of cough and upper respiratory symptoms is well established in adults through clinical trials [29,30,31]. However, our review identified no published randomized controlled trials investigating efficacy of the product in pediatric patients (< 18 years), from which we conclude that efficacy has not been demonstrated in this patient population. A 2016 review of the Cochrane Library also found no evidence either in support of, or opposition to, the use of codeine and its derivatives for the treatment of chronic cough in children [32]. The discrepancy between this up-to-date review and the 1962 DESI process, which found hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine to be effective for pediatric cough relief, highlights the importance of continually re-assessing older, established drugs using modern methods; over 2000 drugs were assessed as having sufficient efficacy for approval within their indicated populations by the DESI review [14].

Current opinion in clinical practice considers that the risks associated with opioid use in pediatric patients for self-limiting conditions such as cough and cold far outweigh any potential benefit of medication [18, 19, 32]. Alternative remedies such as honey [33,34,35,36], vapor rubs [37], and roots of the plant Pelargonium sidoides [38] have been shown to be effective in symptomatic cough relief without the risks that accompany over-the-counter and prescription medications. Furthermore, there is little evidence supporting the use of over-the-counter and prescription cough suppressants in general in children [18, 39,40,41,42]; coughing itself can assist recovery from respiratory infections through clearing the airways [43], so suppression of cough could in fact delay recovery.

5 Conclusion

Given the lack of evidence supporting the efficacy of hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine as an antitussive agent in patients < 18 years of age, together with evidence from review of the manufacturer’s safety database and existing safety concerns within the medical community, this review concludes that the benefit risk profile is not favorable. As communicated by the FDA, hydrocodone/chlorpheniramine should not be indicated for use in the 6 to 18 years patient population, aligning with the restriction already implemented for patients < 6 years old. This case study highlights the importance of regular re-evaluation of the benefit risk profile for existing drugs as new safety and efficacy evidence becomes available in the literature and clinical practice evolves.

References

Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, Balog CC, Benyamin RM, Boswell MV, et al. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for responsible opioid prescribing in chronic non-cancer pain: part 2—guidance. Pain Physician. 2012;15:S67–116.

Califf RM, Woodcock J, Ostroff S. A proactive response to prescription opioid abuse. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(15):1480–5. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1601307.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC grand rounds: Prescription drug overdoses—a U.S. epidemic Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61(1):10–3.

Tadros A, Layman SM, Davis SM, Bozeman R, Davidov DM. Emergency department visits by pediatric patients for poisoning by prescription opioids. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2016;42(5):550–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2016.1194851.

Manchikanti L, Fellows B, Ailinani H, Pampati V. Therapeutic use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids: a ten-year perspective. Pain Physician. 2010;13(5):401–35.

Mikus G, Weiss J. Influence of CYP2D6 genetics on opioid kinetics, metabolism and response. Curr Pharmacogenom. 2005;3(1):43–52. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570160053175018.

Hutchinson MR, Menelaou A, Foster DJR, Coller JK, Somogyi AA. CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 involvement in the primary oxidative metabolism of hydrocodone by human liver microsomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;57(3):287–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2003.02002.x.

Drug Enforcement Administration, U.S Department of Justice. Schedules of controlled substances: rescheduling of hydrocodone combination products from schedule III to schedule II. 21CFR Part 1308 [Docket No. DEA-389]. Federal Register Online. 2014;79(163):49661–49682. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/rules/2014/fr0822.htm.

FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA requires labeling changes for prescription opioid cough and cold medicines to limit their use in adults 18 years and older. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm590435.htm. Accessed March 2018.

FDA. Presentations for the September 11, 2017 Meeting of the Pediatric Advisory Committee. https://www.fda.gov/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/PediatricAdvisoryCommittee/ucm575294.htm. Accessed Jan 2018.

FDA. Tussionex Pennkinetic Extended-Release Suspension label (SUPPL-19). Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/019111s019lbl.pdf. Accessed Nov 2017.

Federal Register. 47(105):23681–23912. 1982.

Anand O, Yu LX, Conner DP, Davit BM. Dissolution testing for generic drugs: an FDA perspective. AAPS J. 2011;13(3):328. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-011-9272-y.

Chhabra R, Kremzner ME, Kiliany BJ. FDA policy on unapproved drug products: past, present, and future. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(7–8):1260–4.

FDA approval letter for NDA 19-111/S-015. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2008/019111s015ltr.pdf. Accessed May 2018.

Labeling supplement (S-015). Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/019111s015lbl.pdf. Accessed May 2018.

FDA. Important informations for the safe use of Tussionex Pennkinetic Extended-Release Suspension—full version. 2008. Available at: https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170722153516/https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugSafetyPodcasts/ucm078908.htm. Accessed Oct 2017.

Paul IM. Therapeutic options for acute cough due to upper respiratory infections in children. Lung. 2012;190:41–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-011-9319-y.

FDA. Joint Pulmonary-Allergy Drugs and Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Comittee Meeting. 2015. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/Pulmonary-AllergyDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM477959.pdf. Accessed Nov 2017.

EMA. Annual Report 2015. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Annual_report/2016/05/WC500206482.pdf. Accessed May 2016.

Tobias JD, Green TP, Coté CJ. Codeine: time to say “no”. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2396.

Gudin J. Opioid therapies and cytochrome P450 interactions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44(6):S4–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.08.013.

Irwin RS, Baumann MH, Bolser DC, Boulet L-P, Braman SS, Brightling CE, et al. Diagnosis and management of cough executive summary: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(1 Suppl):1S–23S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.1S.

Khetani JD, Madadi P, Sommer DD, Reddy D, Sistonen J, Ross CJ, et al. Apnea and oxygen desaturations in children treated with opioids after adenotonsillectomy for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a prospective pilot study. Pediatr Drugs. 2012;14(6):411–5. https://doi.org/10.2165/11633570-000000000-00000.

Liu W, Dutta S, Kearns G, Awni W, Neville KA. Pharmacokinetics of hydrocodone/acetaminophen combination product in children ages 6–17 with moderate to moderately severe postoperative pain. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;55(2):204–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcph.394.

Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Bell CM. Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):425–30. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1827.

Hoppe JA, Kim H, Heard K. Association of emergency department opioid initiation with recurrent opioid use. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(5):493–9.

Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Keyes KM, Heard K. Prescription opioids in adolescence and future opioid misuse. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1169–77. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1364.

Doyle WJ, McBride TP, Skoner DP, Maddern BR, Gwaltney JMJ, Uhrin M. A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of the effect of chlorpheniramine on the response of the nasal airway, middle ear and eustachian tube to provocative rhinovirus challenge. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1988;7(3):229–38.

Homsi J, Walsh D, Nelson KA, Sarhill N, Rybocki L, Legrand SB, et al. A phase II study of hydrocodone for cough in advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2002;19(1):49–56.

Stolz D, Chhajed PN, Leuppi JD, Brutsche M, Pflimlin E, Tamm M. Cough suppression during flexible bronchoscopy using combined sedation with midazolam and hydrocodone: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Thorax. 2004;59(9):773–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2003.019836.

Gardiner SJ, Chang AB, Marchant JM, Petsky HL. Codeine versus placebo for chronic cough in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;7:CD011914. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd011914.pub2.

Paul IM, Beiler J, McMonagle A, Shaffer ML, Duda L, Berlin CM. Effect of honey, dextromethorphan, and no treatment on nocturnal cough and sleep quality for coughing children and their parents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(12):1140–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.12.1140.

Shadkam MN, Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Mozayan MR. A comparison of the effect of honey, dextromethorphan, and diphenhydramine on nightly cough and sleep quality in children and their parents. J Altern Compl Med. 2010;16(7):787–93.

Goldman RD. Honey for treatment of cough in children. Can Fam Physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2014;60(12):1107–10.

Oduwole O, Udoh EE, Oyo-Ita A, Meremikwu MM. Honey for acute cough in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4:Cd007094. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd007094.pub5.

Paul IM, Beiler JS, King TS, Clapp ER, Vallati J, Berlin CM Jr. Vapor rub, petrolatum, and no treatment for children with nocturnal cough and cold symptoms. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):1092–9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-1601.

Lizogub VG, Riley D, Heger M. Efficacy of a Pelargonium Sidoides preparation in patients with the common cold: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. 2007;3:573–584

Chang AB, Glomb WB. Guidelines for evaluating chronic cough in pediatrics: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129:260S–83S.

Department of Child and Adolescent Health and Development. World Health Organization. Cough and cold remedies for the treatment of acute respiratory infections in young children. Geneva, 2001. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/fch_cah_01_02/en/. Accessed May 2018.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Use of codeine- and dextromethorphan-containing cough remedies in children. Pediatrics. 1997;99:918–20.

Schroeder K, Fahey T. Should we advise parents to administer over the counter cough medicines for acute cough? Systematic review of randomized control trials. Arch Dis Child. 2002;86:170–5.

Consolini DM. Cough in Children. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/symptoms-in-infants-and-children/cough-in-children. Accessed Jan 2018.

Peds-info. Withdrawal of cold medicines: addressing parent concerns. Available at: https://dianeslui.wordpress.com/2013/04/23/otc-coughcold-meds/. Accessed May 2018.

US FDA drug and biologic advisory committee meetings. Panel advises removal of codeine from OTC use. Adcomm Bulletin. 2015(IDRAC 222100).

Li Q, Mitchell AA, Werler MM, Yau WP, Hernandez-Diaz S. Antihistamine use in early pregnancy and risk of birth defects. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(6):666–74 e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2013.07.008.

Sauberan JB, Anderson PO, Lane JR, Rafie S, Nguyen N, Rossi SS, et al. Breast milk hydrocodone and hydromorphone levels in mothers using hydrocodone for postpartum pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):611–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820ca504.

Crews KR, Gaedigk A, Dunnenberger HM, Leeder JS, Klein TE, Caudle KE, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for cytochrome P450 2D6 genotype and codeine therapy: 2014 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;95(4):376–82. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2013.254.

Albert RH. Diagnosis and treatment of acute bronchitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(11):1345–50.

Madadi P, Hildebrandt D, Gong IY, Schwarz UI, Ciszkowski C, Ross CJ, et al. Fatal hydrocodone overdose in a child: pharmacogenetics and drug interactions. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):e986–9.

FDA. Information for healthcare professionals: long-acting hydrocodone-containing cough product (marketed as Tussionex Pennkinetic Extended-Release Suspension). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm126196.htm. Accessed Apr 2016.

Fraserhealth Hospice Palliative Care, Clinical Practice Committee. 2006 symptom guidelines: Cough.

Broussard CS, Rasmussen SA, Reefhuis J, Friedman JM, Jann MW, Riehle-Colarusso T et al. Maternal treatment with opioid analgesics and risk for birth defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(4):314 e1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.12.039.

Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: how states can help advance the knowledge base for primary prevention and best practices of care. 2014. http://www.astho.org/prevention/nas-neonatal-abstinence-report/. Accessed Sept 2017.

Bateman BT, Hernandez-Diaz S, Rathmell JP, Seeger JD, Doherty M, Fischer MA, et al. Patterns of opioid utilization in pregnancy in a large cohort of commercial insurance beneficiaries in the United States. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(5):1216–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000000172.

Rayburn WF, Brennan MC. Periconception warnings about prescribing opioids. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(4):281–2.

Flower O, Hellings S. Sedation in traumatic brain injury. Emerg Med Int. 2012;2012:637171. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/637171.

Walsh SL, Nuzzo PA, Lofwall MR, Holtman JR Jr. The relative abuse liability of oral oxycodone, hydrocodone and hydromorphone assessed in prescription opioid abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;98(3):191–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.05.007.

Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, Parrino MW, Severtson SG, Bucher-Bartelson B, et al. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(3):241–8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1406143.

VITUZ® Oral Solution: label. Available at: https://www.drugs.com/pro/vituz-oral-solution.html. Accessed May 2018.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Linda Feighery, PhD CMPP, UCB Pharma Ltd., Slough, UK for publication coordination and Amelia Frizell-Armitage, PhD and Debbie Nixon, DPhil from Costello Medical, Cambridge, UK for medical writing and editorial assistance in preparing this manuscript for publication, based on the authors’ input and direction.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

UCB sponsored the study and the development of the manuscript/publication and reviewed the text to ensure that from UCB perspective, the data presented in the publication are scientifically, technically and medically supportable, that they do not contain any information that has the potential to damage the intellectual property of UCB, and that the publication complies with applicable laws, regulations, guidelines and good industry practice. The authors approved the final version to be published after critically revising the manuscript/publication for important intellectual content.

Conflict of interest

Victor S. Sloan and Chidi Maduka are employees of UCB BioSciences Inc., Alphia Jones is an employee of UCB Inc., and Jürgen W. G. Bentz is an employee of UCB Biopharma SPRL; all four are shareholders of UCB S.A.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sloan, V.S., Jones, A., Maduka, C. et al. A Benefit Risk Review of Pediatric Use of Hydrocodone/Chlorpheniramine, a Prescription Opioid Antitussive Agent for the Treatment of Cough. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 6, 47–57 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-019-0152-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-019-0152-6