Abstract

Gaps in morphological paradigms are often explained in terms of blocking: generating one form is blocked by the existence of a paraphrase. Another way of thinking about paradigm gaps dissociates their existence from competition between forms. Unlike in competition-based approaches, systematic gaps can be seen as true gaps; the system might not generate a certain form, but this form is not considered in comparison to others. Adopting this latter approach, we argue that inflectional paradigms are neither morphosyntactic primitives nor the result of competition. This claim is supported by data from two unrelated languages. For Hebrew, we demonstrate that a passive gap is not the result of competition with analytic paraphrases. For Latin, we show that a cyclic, syntax-based approach is superior to a theory that generates nonactive verbs in the lexicon and has them compete against each other. Systematic paradigm gaps are thus argued to result from syntactic structure building, without competition regulating independent morphological constructions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We thank the reviewers for filling some of the gaps in our acknowledgment of the relevant literature.

We are aware of two other cases similar to the current data: Stump (2001, 230) discusses an analytic future verbal form in Sanskrit which is claimed to block a synthetic one. And Kalvana and Lokmane (2010) report paradigms in Latvian that appear similar to ours. Strikingly, the key Latvian data concern non-active verbal forms, just as in Hebrew and Latin.

Abbreviations used: acc accusative, caus “causative” template, cs Construct State, f feminine, fin finite, imp imperative, Imperf imperfect, inf infinitive, intns “intensive” template, mid “middle” template, nact nonactive, nom nominative, pass passive, passptcp passive/perfect participle, Perf perfect, Pres present, pl plural, refl reflexive, sbj subjunctive, sg singular, th theme vowel. Hebrew transcriptions are given in IPA, with “e” standing in for /Ɛ/ and “r” standing in for /ʁ/. Present forms utilize the present participle, which can be used as a present-tense verb, a nominal or an adjective (Boneh 2013; Doron 2013).

An infinitival synthetic passive has been attested a handful of times in writing. Even so, this happens arguably only in a jocular way in written form, never in actual speech. There is not enough data to generalize from, since this form is exceedingly rare.

An anonymous reviewer asks why the middle template niXYaZ does not show these gaps, even though passive readings can be obtained in it. Doron (2003), Arad (2005) Reinhart and Siloni (2005), Laks (2011) and Kastner (2016) provide various ways of answering this question, all centering around the question of how an anticausative form can also serve to existentially close over an implicit external argument. For present purposes, it is enough to assume that niXYaZ is not derived using the syntactic head Pass motivated below, an assumption which correctly predicts that not every active verb in XaYaZ has a corresponding passive verb in niXYaZ. The latter form can be derived using a non-active head such as Voice\(_{\text{[--D]}}\) from Kastner (to appear).

Examples found via Miller (2010), who calls nact the medio-passive.

See Kiparsky (2005) for brief mentions of Marathi and Sanskrit as well.

This is not to say that complexity measures should be ruled out in general; see Dunbar and Wellwood (2016) for one concrete proposal.

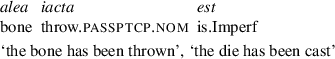

See Embick (2000, 189ff6) on stative readings of the perfect, including “the die is cast.”

For discussion of the intricacies of the Latin perfect participle we thank Larissa Bonfante, David Levene, Matthew Santirocco, William Short and Rex Wallace.

Manuzio, Paolo: Adagia Optimorum Utriusque Linguae Scriptorum Omnia, Quaecunque Ad Hanc Usque diem exierunt: cum plurimis ac locupletissimis indicibus. Ursellis: Ex Officina Cornelii Sutorii, impensis Lazari Zetzneri. Page 170. Retrieved September 2014 from http://www.uni-mannheim.de/mateo/camenaref/manuzio/manuzio1/jpg/s0170.html.

References

Adger, D. (2003). Core syntax: a minimalist approach. London: Oxford University Press.

Adger, D., Béjar, S., & Harbour, D. (2003). Directionality in allomorphy: a reply to Carstairs-McCarthy. Transactions of the Philological Society, 101(1), 109–115.

Albright, A. (2003). A quantitative study of Spanish paradigm gaps. In G. Garding & M. Tsujimura (Eds.), Proceedings of WCCFL (Vol. 22, pp. 1–14). Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Albright, A. (2011). Paradigms. In M. van Oostendorp, C. J. Ewen, E. Hume, & K. Rice (Eds.), The Blackwell companion to phonology (pp. 1972–2001). Oxford: Blackwell Sci.

Alexiadou, A., & Doron, E. (2012). The syntactic construction of two non-active voices: passive and middle. Journal of Linguistics, 48, 1–34.

Alexiadou, A., Gehrke, B., & Schäfer, F. (2014). The argument structure of adjectival participles revisited. Lingua, 149, 118–138.

Arad, M. (2005). Roots and patterns: Hebrew morpho-syntax. Berlin: Springer.

Aronoff, M. (1976). Word formation in generative grammar. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Aronoff, M. (1994). Morphology by itself: stems and inflectional classes. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Arregi, K., & Nevins, A. (2014). A monoradical approach to some cases of disuppletion. Theoretical Linguistics, 40(3/4), 311–330.

Bachrach, A., & Nevins, A. (Eds.) (2008). Inflectional identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baerman, M. (2007). Morphological typology of deponency. In M. Baerman, G. Corbett, D. Brown, & A. Hippisley (Eds.), Deponency and morphological mismatches (pp. 1–19). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baerman, M., Corbett, G., & Brown, D. (Eds.) (2010). Defective paradigms: missing forms and what they tell us. Proceedings of the British Academy: Vol. 163. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bailyn, J. F., & Nevins, A. (2008). Russian genitive plurals are impostors. In A. Bachrach & A. Nevins (Eds.), Inflectional identity (pp. 237–270). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baker, M., Johnson, K., & Roberts, I. (1989). Passive arguments raised. Linguistic Inquiry, 20(2), 219–251.

Bat-El, O. (1994). Stem modification and cluster transfer in Modern Hebrew. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 12, 571–596, doi:10.1007/BF00992928.

Bat-El, O. (2002). Semitic verb structure within a universal perspective. In J. Shimron (Ed.), Language processing and acquisition in languages of semitic, root-based, morphology (pp. 29–59). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Bat-El, O. (2008). Morphologically conditioned v–ø alternation in Hebrew: distinction among nouns, adjectives & participles, and verbs. In S. Armon-Lotem, G. Danon, & S. Rothstein (Eds.), Current issues in generative Hebrew linguistics. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Bermúdez-Otero, R. (2013). The Spanish lexicon stores stems with theme vowels, not roots with inflectional class features. Probus, 25, 3–103.

Bermúdez-Otero, R. (2016). We do not need structuralist morphemes, but we do need constituent structure. In D. Siddiqi & H. Harley (Eds.), Morphological metatheory (pp. 385–428). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Bjorkman, B. (2011). BE-ing default: the morphosyntax of auxiliaries. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Bjorkman, B. (2014). Verbal inflection and overflow auxiliaries. Ms., University of Toronto.

Bobaljik, J. D. (2000). The ins and outs of contextual allomorphy. In K. Grohmann & C. Struijke (Eds.), University of Maryland working papers in linguistics (Vol. 10, pp. 35–71).

Bonami, O. (2015). Periphrasis as collocation. Morphology, 25, 63–110.

Boneh, N. (2013). Tense: Modern Hebrew. In G. Khan (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Hebrew language and linguistics. Leiden: Brill.

Borer, H. (2013). Structuring sense, vol. 3: taking form. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Borer, H., & Wexler, K. (1987). The maturation of syntax. In T. Roeper & E. Williams (Eds.), Parameter setting, studies in theoretical psycholinguistics. Berlin: Springer.

Božič, J. (2017). Non-local allomorphy in a strictly local system. Ms., McGill University. lingbuzz/003469.

Bresnan, J. (2001). Explaining morphosyntactic competition. In M. Baltin & C. Collins (Eds.), Handbook of contemporary syntactic theory (pp. 1–44). Oxford: Blackwell Sci.

Bruening, B. (2013). By phrases in passives and nominals. Syntax, 16, 1–41.

Bruening, B. (2014). Word formation is syntactic: adjectival passives in English. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 32(2), 363–422.

Burzio, L. (1986). Italian syntax. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Calabrese, A. (2015). Irregular morphology and athematic verbs in Italo-Romance. Isogloss, 70, 69–102, doi:10.5565/rev/isogloss.17.

Carstairs-McCarthy, A. (2001). Grammatically conditioned allomorphy, paradigmatic structure, and the Ancestry Constraint. Transactions of the Philological Society, 99(2), 223–245.

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic structures. The Hague: Mouton.

Doron, E. (2000). Habeynoni hasavil [the passive participle]. Balshanut Ivrit [Hebrew Linguistics], 47, 39–62.

Doron, E. (2003). Agency and voice: the semantics of the Semitic templates. Natural Language Semantics, 11, 1–67. doi:10.1023/A:1023021423453.

Doron, E. (2013). Participle: modern Hebrew. In G. Khan (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Hebrew language and linguistics. Leiden: Brill.

Doron, E. (2014). The interaction of adjectival passive and voice. In A. Alexiadou, H. Borer, & F. Schäfer (Eds.), The syntax of roots and the roots of syntax (pp. 164–191). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dunbar, E., & Wellwood, A. (2016). Addressing the ‘two interface’ problem: comparatives and superlatives. Glossa, 1(1), 5, doi:10.5334/gjgl.9.

Embick, D. (2000). Features, syntax and categories in the Latin perfect. Linguistic Inquiry, 31(2), 185–230.

Embick, D. (2004). On the structure of resultative participles in English. Linguistic Inquiry, 35(3), 355–392.

Embick, D. (2007). Blocking effects and analytic/synthetic alternations. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 25, 1–37.

Embick, D. (2010). Localism versus globalism in morphology and phonology. Linguistic inquiry monographs (Vol. 60). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Embick, D., & Marantz, A. (2008). Architecture and blocking. Linguistic Inquiry, 39(1), 1–53.

Embick, D., & Noyer, R. (2001). Movement operations after syntax. Linguistic Inquiry, 32(4), 555–595.

Fanselow, G., & Féry, C. (2002). Ineffability in grammar. In G. Fanselow & C. Féry (Eds.), Resolving conflicts in grammars: optimality theory in syntax, morphology, and phonology, Linguistische Berichte (Vol. 11, pp. 265–307). Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.

Folli, R., & Harley, H. (2008). Teleology and animacy in external arguments. Lingua, 118, 190–202.

Frampton, J. (2001). The amn’t gap, ineffability, and anomalous aren’t: against morphosyntactic competition. In Proceedings of CLS (Vol. 37).

Freese, J. W. (1843). The Latin governess: a manual of instruction in the elements of Latin. London: Mills and Son.

Gildersleeve, B., & Lodge, G. (1903). Latin grammar (3rd ed.). London: Macmillan.

Giorgi, A., & Pianesi, F. (1991). Toward a syntax of temporal representations. Probus, 3, 187–213.

Goldsmith, J. A. (1976). Autosegmental phonology. Doctoral dissertation, Cambridge: MIT.

Gorman, K., & Yang, C. (to appear). When nobody wins. In F. Rainer, F. Gardani, H. C. Luschützky, & W. U. Dressler (Eds.), Competition in inflection and word formation. Dordrecht: Springer.

Gouskova, M., & Ahn, S. (2016). Sublexical phonotactics and english comparatives. Ms., New York University.

Halle, M. (1973). Prolegomena to a theory of word formation. Linguistic Inquiry, 4(1), 3–16.

Halle, M., & Marantz, A. (1993). Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In K. Hale & S. J. Keyser (Eds.), The view from building 20: essays in linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger (pp. 111–176). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Harbour, D. (2003). Some outstanding problems of Yimas. Transactions of the Philological Society, 101(1), 125–136.

Harley, H. (2014a). On the identity of roots. Theoretical Linguistics, 40(3/4), 225–276.

Harley, H. (2014b). Reply to commentaries “On the identity of roots”. Theoretical Linguistics, 40(3/4), 447–474.

Haugen, J. D., & Siddiqi, D. (2013). Roots and the derivation. Linguistic Inquiry, 44(3), 493–517.

Hazout, I. (1995). Action nominalizations and the lexicalist hypothesis. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 13, 355–404.

Higgins, E. T. (1977). The varying presuppositional nature of comparatives. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 6(3), 203–222.

Hippisley, A. (2007). Declarative deponency: a network morphology account of morphological mismatches. In M. Baerman, G. Corbett, D. Brown, & A. Hippisley (Eds.), Deponency and morphological mismatches (pp. 145–173). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Horvath, J., & Siloni, T. (2008). Active lexicon: adjectival and verbal passives. In S. Armon-Lotem, G. Danon, & S. Rothstein (Eds.), Current issues in generative Hebrew linguistics (pp. 105–134). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Horvath, J., & Siloni, T. (2009). Hebrew idioms: the organization of the lexical component. Brill’s Annual of Afroasiatic Languages and Linguistics, 1, 283–310.

Kallulli, D. (2013). (Non-)canonical passives and reflexives: deponents and their like. In A. Alexiadou & F. Schäfer (Eds.), Non-canonical passives, linguistik aktuell/linguistics today (Vol. 205, pp. 337–358). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Kalvana, A., & Lokmane, I. (2010). Defective paradigms of reflexive nouns and participles in Latvian. In M. Baerman, G. Corbett, & D. Brown (Eds.), Proceedings of the British Academy: Vol. 163. Defective paradigms: missing forms and what they tell us (pp. 53–68). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kastner, I. (2016). Form and meaning in the Hebrew verb. Ph.D. thesis, New York University, New York, NY. lingbuzz/003028.

Kastner, I. (2017). Templatic morphology as an emergent property: roots and functional heads in Hebrew. Ms., Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. lingbuzz/003103.

Kastner, I. (to appear). Reflexive verbs in Hebrew: deep unaccusativity meets lexical semantics. Glossa.

Kennedy, C. (2007). Vagueness and grammar: the semantics of relative and absolute gradable adjectives. Linguistics and Philosophy, 30(1), 1–48.

Kiparsky, P. (2005). Blocking and periphrasis in inflectional paradigms. In Yearbook of Morphology, (Vol. 204, pp. 113–135).

Kiparsky, P. (2010). Dvandvas, blocking, and the associative: the bumpy ride from phrase to word. Language, 86(2), 302–331.

Kramer, R. (2014). Clitic doubling or object agreement: the view from Amharic. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 32, 593–634.

Kratzer, A. (2000). Building statives. In L. J. Conathan, J. Good, D. Kavitskaya, A. B. Wulf, & A. C. Yu (Eds.), Proceedings of the twenty-sixth annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, (pp. 385–399). University of California, Berkeley Linguistics Society, Berkeley.

Laks, L. (2011). Morpho-phonological and morpho-thematic relations in Hebrew and Arabic verb formation. Ph.D. thesis, Tel Aviv University, Tel-Aviv.

Laks, L. (2014). Morpho-thematic mismatches in Hebrew: what happens when morphological and thematic criteria collide? Lingua, 138, 107–127.

Legendre, G. (2009). The neutralization approach to ineffability in syntax. In C. Rice & S. Blaho (Eds.), Modeling ungrammaticality in optimality theory. London: Equinox.

Legendre, G., Smolensky, P., & Wilson, C. (1998). When is less more? Faithfulness and minimal links in wh-chains. In P. Barbosa, D. Fox, P. Hagstrom, M. McGinnis, & D. Pesetsky (Eds.), Is the best good enough? Optimality and competition in syntax (pp. 249–289). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Levin, B., & Rappaport, M. (1986). The formation of adjectival passives. Linguistic Inquiry, 17(4), 623–661.

Lieb, H. H. (2005). Notions of paradigm in grammar. In D. A. Cruse, F. Hundsnurscher, M. Job , & P. Lutzeier (Eds.), Lexikologie/Lexicology: ein internationales Handbuch zur Natur und Struktur von Wörtern und Wortschätzen/An international handbook on the nature and structure of words and vocabularies, Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft (Vol. 2, pp. 1613–1646). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Löwenadler, J. (2010). Restrictions on productivity: defectiveness in Swedish adjective paradigms. Morphology, 20, 71–107.

Marantz, A. (2013). Locality domains for contextual allomorphy across the interfaces. In A. Marantz & O. Matushansky (Eds.), Distributed morphology today: morphemes for Morris Halle (pp. 95–115). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Matushansky, O. (2006). Head movement in linguistic theory. Linguistic Inquiry, 37(1), 69–109.

Matushansky, O. (2013). More or better: on the derivation of synthetic comparatives and superlatives in English. In A. Marantz & O. Matushansky (Eds.), Distributed morphology today: morphemes for Morris Halle (pp. 59–78). Cambridge: MIT Press.

McCarthy, J. J. (1981). A prosodic theory of nonconcatenative morphology. Linguistic Inquiry, 12, 373–418.

McCarthy, J. J., & Pater, J. (2016). Harmonic grammar and harmonic serialism. Sheffield: Equinox.

McCarthy, J. J., & Prince, A. S. (1990). Prosodic morphology and templatic morphology. In M. Eid & J. J. McCarthy (Eds.), Perspectives on Arabic linguistics (Vol. 2, pp. 1–54). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

McIntyre, A. (2013). Adjectival passives and adjectival participles in English. In A. Alexiadou & F. Schäfer (Eds.), Non-canonical passives (pp. 21–42). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Meltzer-Asscher, A. (2011). Adjectival passives in Hebrew: evidence for parallelism between the adjectival and verbal systems. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 29(3), 815–855.

Merchant, J. (2015). How much context is enough? Two cases of span-conditioned stem allomorphy. Linguistic Inquiry, 46(2), 273–303.

Miller, D. G. (2010). The mediopassive: Latin to Romance. In Language change and linguistic theory (Vol. 2). Clarendon: Oxford University Press.

Moreland, F. L., & Fleischer, R. M. (1977). Latin: an intensive course. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Müller, G. (2011). Syncretism without underspecification in optimality theory: the role of leading forms. Word Structure, 4(1), 53–103.

Müller, G. (2013). Approaches to deponency. Language and Linguistics Compass, 7(6), 351–369.

Nevins, A. (2015). The exponent list and the encyclopedic list: structurally parallel, mutually mute. In Roots IV. New York: New York University.

Oltra Massuet, I. (1999). On the notion of theme vowel: a new approach to Catalan verbal morphology. Master’s thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

Pertsova, K. (2016). Transderivational relations and paradigm gaps in Russian verbs. Glossa, 1(1), 13 doi:10.5334/gjgl.59.

Pesetsky, D. (1982). Paths and categories. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

Platzack, C., & Rosengren, I. (1998). On the subject of imperatives: a minimalist account of the imperative clause. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics, 1(3), 177–224.

Prince, A., & Smolensky, P. (1993/2004). Optimality theory: constraint interaction in generative grammar. Malden: Blackwell. Revision of 1993, technical report, Rutgers University Center for Cognitive Science. ROA 537.

Reinhart, T., & Siloni, T. (2005). The lexicon-syntax parameter: reflexivization and other arity operations. Linguistic Inquiry, 36(3), 389–436.

Rice, C. (2005). Optimal gaps in optimal paradigms. Catalan Journal of Linguistics, 4, 155–170.

Sadler, L., & Spencer, A. (2001). Syntax as an exponent of morphological features. In Yearbook of Morphology (Vol. 2000, pp. 71–96).

Schäfer, F. (2008). The syntax of (anti-)causatives. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Sichel, I. (2009). New evidence for the structural realization of the implicit external argument in nominalizations. Linguistic Inquiry, 40(4), 712–723.

Spathas, G., Alexiadou, A., & Schäfer, F. (2015). Middle voice and reflexive interpretations: afto-prefixation in Greek. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 33, 1293–1350.

Spencer, A. (2003). Periphrastic paradigms in Bulgarian. In U. Junghanns & L. Szucsich (Eds.), Syntactic structures and morphological information, interface explorations (Vol. 7, pp. 249–282). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Stump, G. T. (2001). Inflectional morphology: a paradigm structure approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stump, G. T. (2006). Heteroclisis and paradigm linkage. Language, 82, 279–322.

Svenonius, P. (2004). Slavic prefixes inside and outside VP. Nordlyd, 32(2), 205–253.

Trommer, J. (2001). Distributed optimality. PhD thesis, University of Potsdam, Potsdam.

Tucker, M. A. (2015). Your roots are showing: on root-sensitive allomorphy in Arabic. In Roots IV. New York: New York University.

Ussishkin, A. (2005). A fixed prosodic theory of nonconcatenative templatic morphology. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 23, 169–218. doi:10.1007/s11049-003-7790-8.

Wasow, T. (1977). Transformations and the lexicon. In P. Culicover, T. Wasow, & A. Akmajian (Eds.), Formal syntax. New York: Academic Press.

Wood, J. (2015). Icelandic morphosyntax and argument structure. Studies in natural language and linguistic theory: Vol. 90. Berlin: Springer.

Wunderlich, D. (2001). How gaps and substitutions can become optimal: the pronominal affix paradigms of Yimas. Transactions of the Philological Society, 99(2), 315–366.

Yang, C. (2016). The price of linguistic productivity. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Zanuttini, R., Pak, M., & Portner, P. (2012). A syntactic analysis of interpretive restrictions on imperative, promissive, and exhortative subjects. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 30(4), 1231–1274.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Bronwyn Bjorkman, Dave Embick, Richie Kayne, Alec Marantz and Neil Myler for comments on previous versions of this article, and to Stephanie Harves, Tal Linzen, Roumi Pancheva, Jim Wood, the NYU Morphology Research Group and the audience at WCCFL 32 for discussion (in particular Rajesh Bhatt, Sabine Iatridou and Alfredo García Pardo). We are also grateful for the highly constructive comments of the reviewers and editor Adam Albright. This research was supported in part by DFG award AL 554/8-1 to Artemis Alexiadou (I.K.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

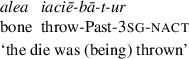

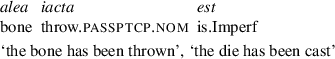

Appendix A: Latin idioms

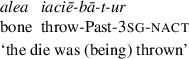

If analytic and synthetic forms are equally Expressive, then a synthetic nonactive perfect and an analytic nonactive perfect must mean the same thing: either both are interpreted literally or both are interpreted idiomatically. Given an idiom in the analytic nonactive perfect, we can ask whether the synthetic form retains the idiomatic reading of the analytic one. For instance, Caesar was famously reported to have said alea iacta est, (61), upon crossing the Rubicon, meaning ‘the die is cast/thrown’, with the idiomatic reading ‘we have passed the point of no return’.Footnote 12 Does the idiomatic meaning exist in the imperfect, (62)?Footnote 13

-

(61)

-

(62)

We do not know for certain. Various complications surround this specific phrase, including that Caesar might have been translating from Greek and that the original quote might have been in the imperative. We have found one occurrence of the imperfect string alea iaciē-bā-t-ur in what seems like a literal sense, but the existence of the literal reading does not preclude the existence of an idiomatic reading.Footnote 14 Some of the classicist scholars we have consulted do think that the idiomatic reading should hold in the imperfect, but there is no consensus on this issue or clear evidence either way.

Another potential datapoint would be the expression acta est fabula, where the literal meaning is ‘the play is done’ and the idiomatic meaning can be taken to mean ‘well that’s the end of it’, even when not necessarily talking about a play. We would then ask whether the same idiomatic meaning would hold for the passive past imperfect fabula agēbātur. If there is a difference to be found between analytic and synthetic forms in Latin as well, it would constitute an additional argument against a competition-based analysis.

Appendix B: Deponency

Deponent verbs have been treated in a number of different theoretical frameworks, as succinctly reviewed by Müller (2013). We contrast these proposals briefly. Müller (2013) divides accounts of deponency into a number of classes, three of which can be straightforwardly applied to Latin. Property deponency has been discussed in the main text on the basis of Embick (2000) and related work, and will not be repeated here.

In form deponency, active verbs are referred to passive morphology, bypassing regular active morphology (Stump 2006). This approach seems plausible, but it does not explain defectivity (Baerman 2007; Müller 2013): the fact that the normal function of passive morphology is no longer available. That is to say, the morphology of Latin deponents does not mark a contrast between active and non-active verbs. Something additional would have to be said in order for this kind of system to be complete. Müller (2013) acknowledges this much for his own OT proposal, speculating that an output-output correspondence constraint could be invoked. In any case, this family of analyses is not demonstrably superior to the one sketched in the main text.

Morphomic deponency accords with the Blocking analysis of Kiparsky (2005) discussed above, and extends to cover Sadler and Spencer (2001) and Hippisley (2007) as well. These approaches correlate morphomic “active” morphology with active syntax and morphomic “non-active” morphology with non-active syntax. Deponents are special in that they do not let the morphological non-active marking be correlated with syntactic non-active. The drawbacks of this approach were highlighted in the main text.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kastner, I., Zu, V. Blocking and paradigm gaps. Morphology 27, 643–684 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-017-9309-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-017-9309-8