Abstract

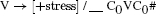

Uspanteko (Guatemala; ∼2000 speakers) is an endangered K’ichean-branch Mayan language. It is unique among the K’ichean languages in having innovated a system of contrastive pitch accent, which operates alongside a separate system of non-contrastive stress. The prosody of Uspanteko is of general typological interest, given the relative scarcity of ‘mixed’ languages employing both stress and lexical pitch. Drawing from a descriptive grammar and from our own fieldwork, we also document some intricate interactions between pitch accent and other aspects of the phonology (stress placement, vowel length, vowel quality, and two deletion processes). While pitch accent is closely tied to morphology, the location of lexical tone is entirely a matter of surface phonology. We propose that the position of pitch accent and stress is determined by three factors: (i) feet are always right-aligned, and preferably iambic; (ii) pitch accent must fall on a stressed syllable; and (iii) pitch accent cannot fall on a final mora. These assumptions derive default final stress, as well as a regular pattern of tone-triggered stress shift. Interactions between prosody and segmental phonotactics are attributed to further constraints on footing. Surprisingly, we find robust evidence for foot structure in Uspanteko, even though these patterns could easily be described in non-metrical terms. Interactions between tone and vowel length also provide evidence for lexical strata within the Uspanteko vocabulary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Since we provide orthographic forms, a number of regular allophonic processes (e.g. nasal place assimilation, initial glottal stop insertion, etc.) are not represented in the data. Such processes are discussed where relevant.

Carlos Gussenhoven (p.c.) has suggested to us that the functional grounding of this constraint might be linked to the fact that Uspanteko has large rising pitch excursions at the ends of phrase-level intonational domains. The language-internal motivation for barring lexical h from final moras, then, is the avoidance of tonal crowding at the right edge of phrases (e.g. Gordon 2000). See also Henderson (2012) for related discussion of phrase-final intonational targets in K’ichee’.

The avoidance of domain-final high tones is well-attested crosslinguistically: for example, see Cassimjee and Kisseberth (2007) and Hyman (2007) on Bantu languages; Pulleyblank (1986) on Margi (Chadic); Kawahara and Shinya (2008) on Japanese; Demers et al. (1999:43) on Yaqui; Silverman and Pierrehumbert (1990) on English (at the phonetic level); various examples in Yip (2002:29,66,90–91); and the general discussion in Hyman (1977).

As for the high […CVVH] tone in Grimes (1971) and Campbell (1977), we suspect that those authors may have misinterpreted phrase-level h tones—which also dock to final stressed syllables—as being instances of lexical tone. Alternatively, their high tone may be our tonal […CV́V], and their low tone our toneless […CVV]. Given the very small number of example words provided by those authors, it’s difficult to determine which of these alternatives is more plausible.

The utterances shown in Figs. 5–9 were produced by a female speaker of Uspanteko in her mid-thirties. This speaker is originally from Uspantán, though for the past few years she has been living in Dueñas, a small town outside of Antigua in Guatemala. For ease of comparison, all phonetic diagrams presented in this paper correspond to productions by this same speaker, recorded over a single three-day period in March 2011.

All tokens were elicited in a phrasal context. For example, we elicited [íntz’i’] ‘my dog’ by asking the question (in Spanish) “Who saw your dog on Monday?”. This prompted a response like [Tek xril íntz’i’ lunes] “Tek saw my dog on Monday”. This method allowed us to elicit target words in phrase-medial position (thereby avoiding interference from phrase-final intonational contours) and in a discourse-given context (thereby avoiding potential interference from focus prosody on the word of interest).

The same reviewer argues that the gently rising pitch contour on the final syllable of [tulul] (Fig. 7) indicates that high pitch is in fact a correlate of stress in Uspanteko. While this may ultimately prove correct, it remains true that pitch perturbations on stressed penults are larger and steeper than corresponding pitch changes on stressed ultimas. It is this asymmetry that motivates our claim that penultimate accent involves an additional phonological h tone.

If duration is indeed a correlate of stress in Uspanteko, we might ask why the final [i] in Figs. 5 and 6 is 105 ms long whether or not it is stressed. While we have not yet conducted a full-scale study of the phonetics of stress in Uspanteko, we suspect that duration is sometimes suppressed as a correlate of stress in word-final syllables, since vowel length is only contrastive in final position. See Berinstein (1979) for discussion of similar facts in the closely-related Mayan languages Kaqchikel and Q’eqchi’; and see Campos-Astorkiza (2007) for general discussion. Alternatively, it may be that duration is a general correlate of stress in Uspanteko, but the phonetic cues of stress are only weakly and irregularly realized, as in many languages with fixed stress (e.g. French and Czech, Cutler 2005; Bengali, Hayes and Lahiri 1991; Bininj Gun-Wok, Bishop 2002).

There are cases of possession in which tone fails to surface for phonological reasons. These cases are discussed and analyzed in later sections.

We thank Judith Aissen for suggesting to us that morphological tone in possessives might be linked to genitive Case.

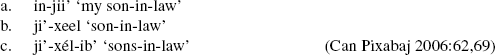

This observation is hinted at in Can Pixabaj (2006:64), and is implicit in some of the examples provided there. Our own fieldwork confirms that the restriction to local person possessors does indeed hold.

Note that, on our account, both tonal insertion and ergative morphology result from the spec-head relation holding between F and the possessor in [spec, FP]. One might then object to this (apparent) functional redundancy: both tone and ergative agreement serve to ‘signal’ possession (as a spec-head relation). On the other hand, functional redundancy of this sort is often found in natural language (e.g. Hockett 1966), so we find it unsurprising that possession is sometimes marked in multiple ways in Uspanteko.

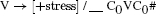

Campbell (1977) proposes the following stress placement rule for Uspanteko:

-

(i)

This rule is an important conceptual precursor to NonFin(T, tbu), in that it marks the penultimate mora (‘V’, in Campbell’s notation) as a privileged position for the realization of accent. However, this rule has several shortcomings: the default position of stress in [CV.CV] words is final, not penultimate; the rule conflates stress and tone, which, as we have argued, should be decoupled (though the two are interdependent); and it is standardly assumed that the syllable, not the mora, is the unit to which stress is assigned (e.g. Hayes 1995; though see Cairns 2002 for a dissenting view).

-

(i)

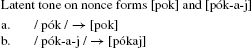

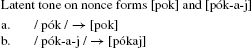

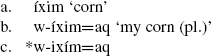

Without further elaboration, the ranking NonFin(T, tbu) ≫ Max(T) predicts that CV(C) roots could have ‘latent’ tone: in the isolation form of the root, underlying tone would be deleted rather than appear on the final mora; but the addition of an affix would allow stem-final tone to surface by insulating it from word-final position.

-

(i)

To the best of our knowledge, there are no words in Uspanteko that manifest latent tone in this way. While our analysis does predict that latent tone should be possible, we believe that the lack of underlying /CV(C), H/ roots is essentially an accidental gap. Most root-types (e.g. verb roots, positional roots, etc.) cannot appear in their unaffixed, isolation forms to begin with. While nominal roots can appear in isolation, there are very few productive nominal affixes, and many nominal affixes bear tone independently, thus obscuring any trace of latent tone on the noun itself.

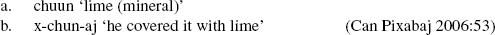

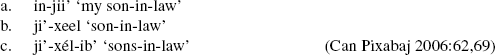

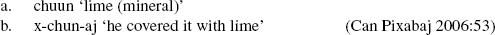

For example, plural [-ib’] and instrumental [-b’Vl] trigger tone (Can Pixabaj, 2006:60), as do the local person ergative possessive prefixes (Sect. 3.1). The third-person ergative prefixes [j-] and [r-] do not trigger tone; but since they do not add a TBU either, they would never cause latent tone to appear. The semi-productive abstractivizing suffix [-VVl] does not trigger tone on its own, but nouns bearing [-VVl] are obligatorily possessed, and may thus bear tone for other reasons (Can Pixabaj, 2006:130). Finally, while the verbalizing suffixes that apply to nouns are toneless (e.g. the [-(a)aj] suffix of derived transitives, Can Pixabaj 2006:123), they are also not fully productive.

If Uspanteko ever had CV(C) noun roots with latent tone, it seems plausible that the toneless, bare forms would have been more frequent than the affixed forms; and further that any tone in affixed nouns could often be attributed to the affix itself. Over time, then, any words with latent tone may have been reanalyzed as simply toneless, in accord with their isolation forms. We thank Larry Hyman for bringing the question of latent tone to our attention.

-

(i)

Furthermore, if violations of alignment constraints are reckoned categorically (McCarthy 2003b), Align-R(H, ω) would not by itself guarantee that stress shifts at most one syllable to the right.

If one were inclined to be more agnostic about iterative footing in Uspanteko, the constraint All-Ft-R could be replaced with a constraint like Align-Head-R, which demands final primary stress but allows for non-final feet (McCarthy and Prince 1993; Pater 2000). Tone-triggered penultimate stress would then require the ranking {NonFin(T, tbu),*Unstressed-H} ≫ Align-Head-R. At present there is no empirical evidence for non-head feet in Uspanteko, so we believe that the burden of proof is on those who assume iterative footing.

Foot-form reversals of this sort—sometimes known as ‘rhythmic reversals’—have also been proposed for Choctaw, Southern Paiute, Ulwa, Axininca Campa (Prince and Smolensky, 1993/2004, 58), Tiriyó Carib (van de Vijver, 1998, Chap. 2), Hopi (Gouskova, 2003, Chap. 3), Nanti (Crowhurst and Michael 2005), Panoan languages (Elias-Ulloa 2006), Takia (de Lacy 2007), and Awajún (McCarthy 2008).

Rather than assume right-aligned feet, one might entertain a foot-free analysis of this two-syllable accent window by appealing to a pressure to avoid word-final lapses (e.g. Kager 2001, 2005). However, see Sect. 3.3 for segmental evidence that Uspanteko accent does indeed depend on metrical foot structure.

Throughout this section, ‘bisyllabic’ refers only to forms consisting of two light syllables, i.e. words with a short vowel in the final syllable.

It is important to note that, according to Can Pixabaj (2006), all of these generalizations are statistical. In combing through this work and the Uspanteko dictionary (Méndez 2007), we have only been able to find one clear counterexample. Ideally we would be able to provide a statistical analysis of this area of the lexicon, but large balanced corpora of Uspanteko that reliably indicate tone do not exist. In the future we hope to be able to quantify the strength of these generalizations. In the meantime, we feel that the fact that native speakers find it easy to think of examples obeying these generalizations, but hard to think of counterexamples, is enough to motivate an analysis of these data.

We have been able to find a few counterexamples, but most are weak at best. For example, the word [síner] ‘dinner’, which is a borrowing from the Spanish cena, should not have tone according to our generalizations; however, this example does not pose a real problem for our account because Spanish penultimate stress is always reinterpreted as tone in borrowings. Similarly, there are words that have been reported inconsistently in the grammatical literature, like ‘his leg’, which is found written both as [ráqan] and as [raqan]. The only firm counterexample we have found is [chukuy] ‘pine fruit’, which does not bear tone despite having two identical short vowels.

It bears mentioning that these shortening effects cannot be attributed to the constraint *UnevenTrochee (55), since *UnevenTrochee would wrongly favor shortening in [o(paa.kost)], *[o(pa.kost)] as well.

Uspanteko also differs from Danish and Serbo-Croatian in that PPW effects are limited to monomorphemic roots. For example, complex forms like [san-s-ik] ‘swollen’ [k’iy-naq] ‘grown’ do not bear tone, while simplex forms like [áb’aj] ‘stone’ do (Can Pixabaj 2006:97,156–157).

See Sect. 4.2 for evidence that tone is also dispreferred on final long vowels for independent reasons. In connection with this fact, note that bisyllabic roots containing a final long vowel (e.g. [tu.kuur] ‘owl’, Can Pixabaj 2006:38) do not bear tone with any notable frequency, even though such words can in principle satisfy all four clauses of PPW (65). We assume that the relative markedness of tonal […CV́VC#] syllables in Uspanteko masks PPW effects in such words.

Along these lines, Kenstowicz (1994), Gouskova (2003), Zec (2003) and de Lacy (2004, 2007) (among others) have suggested that feet may impose different sonority requirements on their strong and weak branches, with a clear preference for high-sonority heads and low-sonority non-heads. Teeple (2009) argues at length that prominence constraints within a phonological domain (like the foot) should refer to both prominent and non-prominent positions simultaneously.

The bisyllabicity requirement also appears to be unique to Uspanteko: in Japanese, for example, PPW makes no distinction between monosyllabic and bisyllabic two-mora words (Itô and Mester 2011). It may be relevant that pitch accent in Tokyo Japanese is an HL contour, and in a certain sense has relative prominence ‘built in’ to the accent itself. See also footnote 30 for an alternative explanation of the bisyllabicity requirement.

Curiously, apart from Uspanteko PPW effects have so far only been observed for languages with trochaic footing. More research is needed to determine whether this is a real generalization about the content of PPW, or an artifact of limited data. Also interesting in this regard is the fact that “…trochaic systems tend to be characterized by alternations in pitch and intensity, while iambic systems are marked by alternations in length” (Goad and Buckley 2006:115, citing Hayes 1995). In PPW contexts in Uspanteko, we find trochaic feet that show prominence asymmetries in both pitch and intensity (≈ sonority), in line with this general finding about the expression of prominence in trochaic stress accent systems.

While there might not be pressure for initial feet to have an internal tone or sonority contrast, there is reason to believe that initial syllables favor prominent elements (e.g. Beckman 1998; Smith 2005). We could abandon the foot-based account in favor of an analysis based on edge prominence, but this would only account for the distribution of tone. That is, while it might make sense to have a constraint penalizing initial toneless syllables, there is no evidence for a constraint demanding that the initial syllable be at least as sonorous as the following syllable regardless of footing. To account for the sonority facts, we would have to resort to the same parameterization mechanism discussed earlier (i.e. PROM/Son init ). The result is that to build an account that decomposes PPW, we either have to fully replicate PPW via stipulative constraint parameterization, or partially replicate it via constraint parameterization and a non-uniform analysis of the tone and sonority patterns in bisyllabic forms.

Syncope in words with penultimate accent is hinted at in Can Pixabaj (2006:71), but essentially ignored.

We also find ablaut feeding syncope under possession. Optional syncope yields [ínch’] for the first-person singular possessed form of [che’] ‘tree’, but it alternates with [ínchi’], not *[ínche’].

The hallmark of this sort of vowel reduction is that the vowel nucleus is still active for phonological processes. While we need to do more work to confirm whether or not syncope affects syllable-based consonant allophony (stop aspiration, nasal place assimilation, etc.; see Can Pixabaj 2006:Chap. 2), Uspanteko syncope does have a number of affinities with the syllable-preserving syncope of Macushi Carib. For one, it is variable, and to some extent gradient: non-syncopated weak vowels are reduced to various degrees, and syncope seems to be an endpoint for this gradient reduction. Syncope also derives many clusters that are otherwise unattested in the language (e.g. [chk], as in [chkuy] ‘pine fruit’). As Larry Hyman suggests to us, the fact that syncope derives otherwise illicit clusters (a property which it shares with schwa deletion in French; e.g. Dell 1995) might point to the preservation of a mora or vocalic nucleus at the phonological level.

In (95) and (96) -iik marks an inalienably possessed noun in its unpossessed form, hence the equivalent glosses.

There are also some nouns that lengthen under possession: for example, [k’aj] ‘wheat’ becomes [in-k’áaj] ‘my wheat’ (Can Pixabaj 2006:70). Lengthening under possession is a common morphophonemic change in K’ichean-branch Mayan languages (see Dayley 1985 for Tz’utujil, and Campbell 1977 on Proto-K’ichean), and is plausibly not phonological in character.

Cophonologies of this sort generally arise as a result of language contact (e.g. Fries and Pike 1949; Itô and Mester 1995 and related work). Given the lack of large-scale historical work on Uspanteko, it is not currently possible to determine whether the cophonologies we propose correspond to borrowings from different source languages. However, it would be unsurprising if these cophonologies did have their origin in language contact: despite being geographically isolated, Uspanteko speakers have been in contact with speakers of K’ichee’, Q’eqchi’, and the more distantly related language Ixil for a very long time.

We assume that the ranking Max(T) ≫ Iamb holds more generally in Uspanteko (see Fig. 10 which shows this), since foot-form reversals normally occur in order to realize underlying tone on penultimate short vowels.

References

Aissen, Judith. 1999. External possessor and logical subject in Tz’utujil. In External possession, eds. Doris Payne and Immanuel Barshi. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Anttila, Arto. 2002. Morphologically conditioned phonological alternations. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 20 (1): 1–42.

Baković, Eric. 2011. Opacity and ordering. In The handbook of phonological theory, 2nd edn., eds. John Goldsmith, Alan C. L. Yu, and Jason Riggle, 40–67. Malden: Wiley–Blackwell.

Barnes, Jonathan. 2006. Strength and weakness at the interface: positional neutralization in phonetics and phonology. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Beckman, Jill. 1998. Positional faithfulness. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Benua, Laura. 2000. Phonological relations between words. New York: Garland.

Berinstein, Ava E. 1979. A cross-linguistic study on the perception and production of stress. Master’s thesis, University of California Los Angeles. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/0t0699hc.

Bishop, Judith. 2002. Stress accent without phonetic stress: accent type and distribution in Bininj Gun-Wok. In Proceedings of the speech prosody 2002 conference, eds. Bernard Bel and Isabelle Marlien, 179–182.

Blumenfeld, Lev. 2006. Constraints on phonological interactions. PhD diss., Stanford University.

Bollinger, Dwight. 1958. A theory of pitch accent in English. Word 14: 109–149.

Bruce, Gösta. 1977. Swedish word accents in sentence perspective. LiberLäromedel/Gleerup.

Buckley, Eugene. 1998. Iambic lengthening and final vowels. International Journal of American Linguistics 64 (3): 179–223.

Cairns, Charles. 2002. Foot and syllable in Southern Paiute City. University of New York.

Campbell, Lyle. 1977. Quichean linguistic prehistory. Vol. 81 of University of California publications in linguistics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Campos-Astorkiza, Rebeka. 2007. Minimal contrast and the phonology-phonetics interaction. PhD diss., University of Southern California.

Can Pixabaj, Telma. 2006. Gramática descriptiva Uspanteka. Oxlajuuj Keej Maya’ Ajtz’iib’ (OKMA).

Cassimjee, Farida, and Charles Kisseberth. 2007. Optimal domains theory and Bantu tonology: a case study from Isixhosa and Shingasidja. In Theoretical aspects of Bantu tone, eds. Larry Hyman and Charles Kisseberth, 33–132. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: a life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Clements, G. N. 1990. The role of the sonority cycle in core syllabification. In Papers in laboratory phonology I: Between the grammar and the physics of speech, eds. John Kingston and Mary Beckman, 283–333. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crowhurst, Megan, and Lev Michael. 2005. Iterative footing and prominence-driven stress in Nanti (Kampa). Language 81 (1): 47–95.

Cutler, Anne. 2005. Lexical stress. In The handbook of speech perception, eds. David Pisoni and Robert Remez, 264–289. Malden: Blackwell.

Dayley, Jon. 1985. Tzutujil grammar. Vol. 107 of University of California publications in linguistics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

de Lacy, Paul. 2002. The interaction of tone and stress in Optimality Theory. Phonology 19 (1): 1–32.

de Lacy, Paul. 2004. Markedness conflation in Optimality Theory. Phonology 21 (2): 145–199.

de Lacy, Paul. 2007. The interaction of tone, sonority, and prosodic structure. In The Cambridge handbook of phonology, ed. Paul de Lacy, 281–307. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dell, François. 1995. Consonant clusters and phonological syllables in French. Lingua 95 (1–3): 5–26.

Dell, François, and Mohamed Elmedlaoui. 1985. Syllabic consonants and syllabification in Imdlawn Tashlhiyt Berber. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 7 (2): 105–130.

Demers, Richard, Fernando Escalante, and Eloise Jelinek. 1999. Prominence in Yaqui words. International Journal of American Linguistics 65 (1): 40–55.

Elias-Ulloa, José. 2006. Theoretical aspects of Panoan metrical phonology: disyllabic footing and contextual syllable weight. PhD diss., Rutgers University.

Embick, David, and Morris Halle. 2005. On the status of stems in morphological theory. In Romance languages and linguistic theory 2003: selected papers from “Going Romance” 2003, Nijmegen, 20–22 November.

Embick, David, and Rolf Noyer. 2007. Distributed Morphology and the syntax/morphology interface. In The Oxford handbook of linguistic interfaces, eds. Gillian Ramchand and Charles Reiss, 289–324. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Flack, Kathryn. 2009. Constraints on onsets and codas of words and phrases. Phonology 26 (2): 269–302.

Fries, Charles, and Kenneth Pike. 1949. Coexistent phonemic systems. Language 25 (1): 29–50.

Fry, Dennis. 1955. Duration and intensity as physical correlates of linguistic stress. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 27 (4): 765–768.

Goad, Heather, and Meaghen Buckley. 2006. Prosodic structure in child French: evidence for the foot. Catalan Journal of Linguistics 5: 109–142.

Gordon, Matthew. 2000. The tonal basis of final weight criteria. In Chicago linguistics society (CLS) 36, eds. Akira Okrent and John P. Boyle, 141–156. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Gordon, Matthew, and Ayla Applebaum. 2010. Prosodic fusion and minimality in Kabardian. Phonology 27 (1): 45–76.

Gordon, Matthew, and Peter Ladefoged. 2001. Phonation types: a cross-linguistic overview. Journal of Phonetics 29 (4): 383–406.

Gouskova, Maria. 2003. Deriving economy: syncope in Optimality Theory. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Green, Thomas, and Michael Kenstowicz. 1995. The Lapse constraint. Ms., MIT. Available online as ROA-101, Rutgers Optimality Archive, http://roa.rutgers.edu/.

Grimes, James. 1971. A reclassification of the Quichean and Kekchian (Mayan) languages. International Journal of American Linguistics 37 (1): 15–19.

Gussenhoven, Carlos. 2004. The phonology of tone and intonation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from Building 20, 111–176. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1994. Some key features of Distributed Morphology. In MIT working papers in linguistics, Vol. 21, 275–288. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Harley, Heidi, and Rolf Noyer. 1999. State-of-the-article: Distributed Morphology. Glot International 4 (4): 3–9.

Hayes, Bruce. 1981. A metrical theory of stress rules. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club. Revised version of 1980 MIT Ph.D. thesis.

Hayes, Bruce. 1995. Metrical stress theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hayes, Bruce, and Aditi Lahiri. 1991. Bengali intonational phonology. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 9 (1): 47–96.

Henderson, Robert. 2012. Morphological alternations at the intonational phrase edge. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 30(3): 741–787.

Hockett, Charles. 1966. The problem of universals in language. In Universals of language, 2nd edn., ed. Joseph Greenberg, 1–29. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hyman, Larry. 1977. On the nature of linguistic stress. In Studies in stress and accent, ed. Larry Hyman. Vol. 4 of Southern California occasional papers in linguistics, 37–82. Los Angeles: University of Southern California.

Hyman, Larry. 1981. Tonal accent in Somali. Studies in African Linguistics 12 (2): 169–203.

Hyman, Larry. 2006. Word-prosodic typology. Phonology 23 (2): 225–257.

Hyman, Larry. 2007. Universals of tone rules: 30 years later. In Tones and tunes: typological studies in word and sentence prosody, eds. Tomas Riad and Carlos Gussenhoven, Vol. 1, 1–34. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Icke, Ignacio. 2007. Map of Guatemalan languages. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Idiomasmap.svg#metadata. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 and the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License, Version 3.0 Unported.

Inkelas, Sharon. 1990. Prosodic constituency in the lexicon. New York: Garland.

Inkelas, Sharon, and Cheryl Zoll. 2007. Is grammar dependence real? A comparison between cophonological and indexed constraint approaches to morphologically conditioned phonology. Linguistics 45 (1): 133–171.

Itô, Junko, and Armin Mester. 1995. The core-periphery structure of the lexicon and constraints on reranking. In Papers in Optimality Theory, eds. Jill Beckman, Laura Walsh Dickey, and Suzanne Urbanczyk, 181–209. Amherst: GLSA Publications.

Itô, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2007. Prosodic adjunction in Japanese compounds. In Formal approaches to Japanese linguistics (FAJL) 4, eds. Yoichi Miyamoto and Masao Ochi, 97–111. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Itô, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2009. The extended prosodic word. In Phonological domains: universals and deviations, eds. Janet Grijzenhout and Bariş Kabak, 135–194. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Itô, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2011. The perfect prosodic word and the sources of unaccentedness. Ms., University of California, Santa Cruz.

Jespersen, Otto. 1904. Lehrbuch der phonetik. Leipzig: Teubner.

Jun, Sun-Ah. 2005. Prosodic typology. In Prosodic typology: the phonology of intonation and phrasing, ed. Sun-Ah Jun, 430–458. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kager, René. 1993a. Alternatives to the iambic-trochaic law. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 11 (3): 381–432.

Kager, René. 1993b. Shapes of the generalized trochee. In West Coast conference on formal linguistics (WCCFL) 11, ed. Jonathan Mead, 298–312. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Kager, René. 1997. Rhythmic vowel deletion in Optimality Theory. In Derivations and constraints in phonology, ed. Iggy Roca, 463–499. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kager, René. 1999. Optimality Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kager, René. 2001. Rhythmic directionality by positional licensing. Handout at Fifth HIL Phonology Conference, University of Potsdam.

Kager, René. 2005. Rhythmic licensing theory: an extended typology. In Proceedings of the third international conference on phonology, 5–31. Seoul: The Phonology-Morphology Circle of Korea.

Kaufman, Terrence. 1974. Idiomas de Mesoamerica. Seminario de Integración Social Guatemalteca.

Kaufman, Terrence. 1990. Algunos rasgos estructurales de los idiomas mayances con referencia especial al K’iche’. In Lecturas sobre la lingüística maya, eds. Nora England and Stephen Elliott, 59–114. La Antigua: Centro de Investigaciones Regionales de Mesoamérica.

Kawahara, Shigeto, and Takahito Shinya. 2008. The intonation of gapping and coordination in Japanese: evidence for intonational phrase and utterance. Phonetica 65 (1–2): 62–105.

Kenstowicz, Michael. 1994. Sonority-driven stress MIT. Available online as ROA-33, Rutgers Optimality Archive, http://roa.rutgers.edu/.

Kitagawa, Yoshihisa. 1986. Subjects in Japanese and English. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Kubozono, Haruo. 2008. Japanese accent. In The handbook of Japanese linguistics, eds. Shigeru Miyagawa and Mamoru Saito, 165–191. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ladefoged, Peter, and Ian Maddieson. 1996. The sounds of the world’s languages. Malden: Blackwell.

Liberman, Mark. 1975. The intonational system of English. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Liberman, Mark, and Alan Prince. 1977. On stress and linguistic rhythm. Linguistic Inquiry 8 (2): 249–336.

Manzini, Rita. 1983. Restructuring and reanalysis. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Marantz, Alec. 1991/2000. Case and licensing. In Arguments and case: explaining Burzio’s generalization, ed. Eric Reuland, 11–30. Amsterdam: Benjamins. Originally appeared 1991 in Proceedings of the Eastern States Conference on Linguistics (ESCOL) 8, Ohio State University Department of Linguistics.

McCarthy, John. 1986. OCP effects: gemination and antigemination. Linguistic Inquiry 17 (2): 207–263.

McCarthy, John J. 2003a. Comparative markedness. Theoretical Linguistics 29 (1–2): 1–51.

McCarthy, John J. 2003b. OT constraints are categorical. Phonology 20: 75–138.

McCarthy, John J. 2008. The serial interaction of stress and syncope. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 26 (3): 499–546.

McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1993. Generalized alignment. In Yearbook of morphology. Available online as ROA-7, Rutgers Optimality Archive, http://roa.rutgers.edu/.

McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1994. The emergence of the unmarked: optimality in prosodic morphology. In Proceedings of NELS, ed. Mercè Gonzàlez, Vol. 24, 333–379.

McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1995. Faithfulness and reduplicative identity. In University of Massachusetts occasional papers in linguistics, eds. Jill Beckman, Laura Walsh Dickey, and Suzanne Urbanczyk, 249–384.

Méndez, Miguel Angel Vicente. 2007. Diccionario bilingüe uspanteko-español. Oxlajuuj Keej Maya’ Ajtz’iib’.

Mester, Armin. 1994. The quantitative trochee in Latin. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 12 (1): 1–61.

Michael, Lev. 2010. The interaction of tone and stress in the prosodic system of Iquito (Zaparoan). In UC Berkeley Phonology Lab annual report, 57–79. Department of Linguistics, UC Berkeley. Available online at http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/phonlab/annual_report/documents/2010/Iquito_prosody_BRILL_v8.pdf.

Myers, Scott. 1998. Surface underspecification of tone in Chichewa. Phonology 15 (3): 367–391.

Myers, Scott, and Benjamin Hansen. 2007. The origin of vowel length neutralization in final position: evidence from Finnish speakers. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 25 (1): 157–193.

Nelson, Nicole. 2003. Asymmetric anchoring. PhD diss., Rutgers University.

Nevins, Andrew. 2007. The representation of third person and its consequences for person-case effects. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 25 (2): 273–313.

Pater, Joe. 2000. Non-uniformity in English secondary stress: the role of ranked and lexically specific constraints. Phonology 17 (2): 237–274.

Prince, Alan. 1991. Quantitative consequences of rhythmic organization. In Cls 26(2): papers from the parasession on the syllable in phonetics and phonology, eds. Karen Deaton, Manuela Noske, and Michael Ziolkowski, 355–398. Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Society.

Prince, Alan, and Paul Smolensky. 1993/2004. Optimality Theory: constraint interaction in generative grammar. Malden: Blackwell. Revision of 1993 technical report, Rutgers University Center for Cognitive Science. Available online as ROA-537, Rutgers Optimality Archive, http://roa.rutgers.edu/.

Pruitt, Kathryn. 2010. Serialism and locality in constraint-based metrical parsing. Phonology 27 (3): 481–526.

Pulleyblank, Douglas. 1986. Tone in lexical phonology. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Pye, Clifton. 1983. Mayan telegraphese: intonational determinants of inflectional development in Quiche Mayan. Language 59 (3): 583–604.

Richards, Michael. 2003. Atlas lingüístico de Guatemala. Instituto de Lingüístico y Educación de la Universidad Rafael Landívar.

Selkirk, Elisabeth. 2011. The syntax-phonology interface, 2nd edn. In Handbook of phonological theory, eds. John Goldsmith, Alan C. L. Yu, and Jason Riggle. Blackwell handbooks in linguistics series, 435–484. Malden: Wiley–Blackwell.

Silverman, Daniel. 1997. Laryngeal complexity in Otomanguean vowels. Phonology 14 (2): 235–261.

Silverman, Kim, and Janet Pierrehumbert. 1990. The timing of pre-nuclear high accents in English. In Papers in laboratory phonology I: Between the grammar and the physics of speech, eds. John Kingston and Mary Beckman, 72–106. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, Jennifer. 2005. Phonological augmentation in prominent positions. London: Routledge.

Steriade, Donca. 2000. Paradigm uniformity and the phonetics-phonology boundary. In Papers in laboratory phonology V: Acquisition and the lexicon, eds. Michael Broe and Janet Pierrehumbert, 313–334. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Teeple, David. 2009. Biconditional prominence correlation. PhD diss., University of California, Santa Cruz.

Trubetzkoy, Nikolai. 1939. Grundzüge der phonologie. Prague: Travaux du cercle linguistique de Prague. English translation published 1969 as Principles of phonology, trans. C.A.M. Baltaxe. Berkeley: University of California Press.

van de Vijver, Ruben. 1998. The iambic issue: iambs as a result of constraint interaction. The Hague: Holland Academic Graphics.

van der Hulst, Harry, and Norval Smith. 1988. The variety of pitch accent systems: introduction. Dordrecht: Foris Publications.

van der Hulst, Harry, Keren Rice, and Leo Wetzels. 2010. Accentual systems in the languages of Middle America. In A survey of word accentual patterns in the languages of the World, eds. Rob Goedemans, Harry van der Hulst, and Ellen van Zanten, 249–312. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Vogel, Irene. 2009. Universals of prosodic structure. In Universals of language today, eds. Sergio Scalise, Elisabetta Magni, and Antonietta Bisetto, 59–82. Berlin: Springer.

Woolford, Ellen. 1997. Four-way case systems: ergative, nominative, objective and accusative. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 15 (1): 181–227.

Yip, Moira. 2002. Tone. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zec, Draga. 1999. Footed tones and tonal feet: rhythmic constituency in a pitch-accent language. Phonology 16 (2): 225–264.

Zec, Draga. 2003. Prosodic weight. In The syllable in Optimality Theory, eds. Caroline Féry and Ruben van de Vijver, 123–143. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zec, Draga and Elizabeth Zsiga. 2010. Interaction of tone and stress in Standard Serbian. In Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics (FASL) 18, eds. Wayles Browne, Adam Cooper, Alison Fisher, Esra Kesici, and Nikola Predolac, 536–555. Ann Arbor: Michigan Slavic Publications.

Acknowledgements

Above all we thank our primary Tz’unun Kaab’ (Uspanteko) consultants Juana Ajpoop Tikiram and Miguel Pinula Pacheco, as well as Juan Us and the rest of the Comunidad Lingüística Uspanteka. This paper was substantially improved by feedback from Judith Aissen, Melissa Frazier, Maria Gouskova, Larry Hyman, Junko Itô, Armin Mester, and the participants in the Winter 2010 Pitch Accent seminar at UC Santa Cruz. We are also grateful to audiences at the 2010 International Symposium on Accent and Tone in Tokyo, the CUNY Conference on the Phonology of Endangered Languages, and the UC Berkeley Fieldwork Forum for comments on this work. Finally, we thank three anonymous reviewers for helping us to strengthen our argumentation. The authors’ names appear in alphabetical order.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Domain effects

Appendix: Domain effects

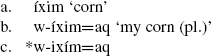

Up till this point we have assumed that, in Uspanteko, metrical structure is built with respect to the right edge of the prosodic word (ω). This view is complicated by certain prosodic effects found with cliticization. Uspanteko has a number of enclitics (at least emphatic [=i’(n)] and plural [=aq]) that disrupt otherwise exceptionless phonological generalizations (Can Pixabaj 2006:52–53). As discussed in Sect. 3, long vowels are restricted to final position within the word.

-

(118)

-

(119)

However, unlike true suffixes, enclitics fail to trigger shortening of final long vowels.

-

(120)

-

(121)

Similarly, tone is normally restricted to the penultimate mora (Can Pixabaj 2006:62–69,etc.).

-

(122)

-

(123)

-

(124)

But when enclitics appear, they fail to trigger rightward tone shift.

-

(125)

Finally, even in toneless forms enclitics do not affect the position of accent on their preceding hosts. As Figs. 12 and 13 illustrate, final stress (as cued by phonetic vowel lengthening) stays in place when followed by the plural enclitic [=aq].

We conclude from these facts that the building of metrical structure, and thus the assignment of tone and stress accent, occurs within the minimal prosodic word (ω min ) in Uspanteko (e.g. Inkelas 1990; Itô and Mester 2007; Itô and Mester 2009). On the assumption that enclitics like [=i’(n)] and [=aq] adjoin to the minimal prosodic word, the prosodic structure of their hosts is correctly predicted to remain unaltered by encliticization. Given the volume and frequency of clitics in Uspanteko (and in Mayan languages more generally), there is no doubt more to say about the prosodic phonology of cliticization; for now, we leave these questions open for future research.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bennett, R., Henderson, R. Accent in Uspanteko. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 31, 589–645 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9196-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9196-6