Abstract

Using data from the Netherlands-based Criminal Career and Life-course Study the effect of first-time imprisonment between age 18–38 on the conviction rates in the 3 years immediately following the year of the imprisonment was examined. Unadjusted comparisons of those imprisoned and those not imprisoned will be biased because imprisonment is not meted out randomly. Selection processes will tend to make the imprisoned group disproportionately crime prone compared to the not imprisoned group. In this study group-based trajectory modeling was combined with risk set matching to balance a variety of measurable indicators of criminal propensity. Findings indicate that first-time imprisonment is associated with an increase in criminal activity in the 3 years following release. The effect of imprisonment is similar across offence types.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

All cases ruled upon by a judge and all cases ‘dismissed for policy reasons’ or ‘dismissed for technical reasons’—for example due to failing evidence—by the Public Prosecutor.

Note that in the Netherlands a person is not given a ‘blank sheet’ upon becoming an adult. The extracts used thus contain information on both juvenile and adult offenses.

While the penal regime in the Netherlands has become harsher over the years, still more than 80% of the unsuspended custodial sanctions imposed in 1999 (most recent numbers available) were below 12 months. Similar percentages were found in many other European countries such as Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland (WODC 2003).

To estimate post-treatment yearly conviction rates taking into account the time offenders were ‘on the street’ and at risk of committing an offense, we calculated the conviction rates only over the period not incarcerated.

While neither official nor self-report data provide a ‘true’ measure of an individual’s criminal behavior (Farrington 1986), we recognize that addressing issues of recidivism based on convictions might introduce bias. If prisons are indeed ‘schools of crime’ it could be the case that ex-prisoners actually commit more crimes than those not imprisoned, but that at the same time have better learned to go about undetected. The use of conviction data will then underrate the actual recidivism of the ex-prisoners thereby masking actual differences between the imprisoned and not imprisoned group. Thus, to the extent ex-prisoners learn to avoid detection more so than non-imprisoned, convictions may underestimate recidivism for ex-prisoners. On the other hand, the use of conviction data may also result in an overestimate of the treatment effects. Police may be more vigilant towards ex-prisoners and Public Prosecutors may be more inclined to press charges. Yet, given that the police are not always conscious of the adjudication of a particular criminal case, their vigilance is most probably triggered by knowing the offender, rather than his sentence. In addition note that in this study discretionary dismissals by the Public Prosecutor are also counted under convictions, thereby dispelling this possible source of bias at least at the Prosecutors level. It is impossible to judge the overall effects of these potential sources of bias but it is important to keep in mind that all measures of criminality including self reports suffer from comparably important sources of bias.

Note that since were are interested in the probability of imprisonment conditional on being convicted at time t, propensity score estimates are based on the 5,264 person-years—out of which 1,475 coded as ‘imprisoned’—in which people were convicted.

The Dutch suspended sentence is a hybrid form of the Belgian-French sursis and the Anglo-Saxon probation. A suspended sentence means the non-implementation of an imposed sentence. A prison sentence up to 1 year may be suspended totally or in part. Prison sentences between 1 and 3 years may be suspended for a maximum of one-third of the total sentence. Prison sentences of over 3 years may not be suspended at all. Other community sanctions include electronic monitoring (Tak 2003).

Specifically, the outcome estimates and their standard errors were calculated as follows: Let:

\( T_{t} = {\frac{1}{{N_{t} }}}\sum\limits_{i}^{{N_{\text{t}} }} {\left[ {y_{\text{it}}^{\text{im}} - \left( {{\frac{1}{{n_{\text{i}} }}}\sum\limits_{j}^{{n_{\text{i}} }} {y_{\text{ijt}}^{\text{c}} } } \right)} \right]} \)

where, i, an index of the ith imprisoned individual from a total set of N t individuals imprisoned in t; n i, the number of controls matched to the ith imprisoned individual; j, an index of the jth of the n i controls matched to i; \( y_{\text{it}}^{\text{im}} \), i’s conviction rate in the 3 year period immediately following t; \( y_{\text{ijt}}^{\text{c}} \), the conviction rate of the jth control matched to i in the 3 years period following i’s imprisonment in t; T t, estimated effect of imprisonment at age t.

If n i were constant across i, T t could be estimated as the difference in the average of \( y_{\text{it}}^{\text{im}} \) and the average of \( y_{\text{ijt}}^{\text{c}} \). However, if ni is variable this “difference of the grand means” calculation is not correct. The correct calculation is the average of the individual differences between the imprisoned individual’s response and the average response of that treated individual’s matched controls.

The variability of n i also must be taken into account in computing the standard error of T t. Assuming that \( y_{\text{it}}^{\text{im}} \) and\( y_{\text{ijt}}^{\text{c}} \), respectively have constant variances σm and σc, the standard error of the estimate Tt is \( {\frac{1}{{N_{\text{t}} }}}\left[ {\sum\limits_{i}^{{N_{\text{t}} }} {\left( {\sigma_{m}^{2} + {\frac{{\sigma_{c}^{2} }}{{n_{i} }}}} \right)} } \right]^{1/2} \)

where σim and σc are be estimated by the sample standard deviations of \( y_{\text{it}}^{\text{im}} \) and \( y_{\text{ijt}}^{\text{c}} \).

Note that an increase in the number of controls matched to each ith imprisoned individual (n i) disproportionally reduces the size of the standard error of the estimate of the treatment effect. This is the reason why we match up to three controls instead matching up to a single control.

Overall, the justice systems in the US and Netherlands are in many ways similar—both have the same court personnel consisting of judges, prosecutors and defense counsel, both countries provide similar due process rights, and both utilize prison as the most serious sentencing option for offenders. However, a number of key differences also define the two justice systems. Plea bargaining dominates the American system but does not exist in the Netherlands, and juries are a key component of trials in the US but they are not used in the Netherlands. Instead the Dutch system relies on a panel of three judges to determine guilt and sentence. While the American system is more adversarial, relying on cross-examination of witnesses, Dutch judges rely heavily on information in case files.

To allow for non linear relationship between age and imprisonment risk we also included age and age-squared as explanatory variables in the propensity score model.

The measure of offense severity ranges from 0 to 20. To improve the interpretation of the coefficients for the effects of type of offense dummies we centered the offense severity around the means of the corresponding offense dummies. For Opium and Gun Law offenses no offense severity measure was available.

The final category in Monahan’s taxonomy measures what has been done to the individual. For this category we have no measurements but here we note that our extensive data on prior record is at least in part controlling for the enduring effects of early life experiences.

In estimating the propensity scores only main effects of covariates were estimated—and no interaction terms (see Table 1).

Some readers might question the use of individuals who are imprisoned after t as matched controls for individuals imprisoned at t. For such readers it is important to keep in mind several points. First, if we were reporting the results of a randomized experiment in which controls were sentenced to a non-custodial sanction, some of these individuals might subsequently be incarcerated for another offense. If they were excluded from the analysis the bias protection from randomization would be vitiated. Similarly if we were to exclude the later imprisoned as potential matches, this would have in fact been a source of bias. Second, it is important to keep in mind that treatments are administered at specific points in time and that treatment at time t does not in general preclude treatment or not at a later date. Consequently, treatment effects should be understood to be possibly time dependent. For a fuller discussion of these issues see Li et al. 2001).

The formula for the standardized difference statistic—in percentages—as suggested by Rosenbaum and Rubin (1985:36) is:

\( D = \left( {{\frac{{\bar{X}_{\text{w}} - \bar{X}_{\text{n}} }}{{\sqrt {{\frac{{s_{\text{w}}^{2} + s_{\text{n}}^{2} }}{2}}} }}}} \right) \times 100 \)

One reviewer suggested that the practice of setting aside individuals with no suitable matches created rather than prevented bias. We strongly disagree. The individuals for whom we were unable to identify suitable matches all had very high probabilities of imprisonment. This was because they had very long criminal records and/or had been convicted of very serious crimes. These are precisely the types of variables which if left unaccounted for may seriously bias treatment effect estimates. Thus, to have included them in the analysis despite the fact that we had no suitable matches increases rather than decreases the risk of bias.

We also note that the US itself is very large and diverse country. For this reason it is not self evident that findings based on a Hispanic population from the Southwestern US are any more generalizable to rural New England than are results from the Netherlands.

Note that having been incarcerated may make it more likely that, ceteris paribus, an individual will subsequently be convicted of a later crime, as a result of a labeling process by judges. That is, if the take prior prison time as indicators of bad character, they might suffice with less tangible evidence to reach a guilty verdict.

References

Adams MS (1996) Labeling and differential association: towards a general learning theory of crime and deviance. Am J Crim Justice 20:149–164. doi:10.1007/BF02886923

Aegisdottir S, White MJ, Spengler PM, Maugherman AS, Anderson LA, Cook RS, Nichols CN, Lampropoulos GK, Walker BS, Cohen G et al (2006) The meta-analysis of clinical judgment project: fifty-six years of accumulated research on clinical versus statistical prediction. Couns Psychol 34:341–382. doi:10.1177/0011000006286696

Barton WH, Butts JA (1990) Viable options: intensive supervision programs for juvenile delinquents. Crime Delinq 36(2):238–256. doi:10.1177/0011128790036002004

Beccaria C (1995) On crimes and punishments and other writings. In: Bellamy R (ed) (trans: Davies R). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bergman GR (1976) The evaluation of an experimental program designed to reduce recidivism among second felony criminal offenders. PhD Dissertation, Wayne State University, Detroit

Bernburg JG, Krohn MD (2003) Labeling, life chances, and adult crime: the direct and indirect effects of official intervention in adolescence on crime in early adulthood. Criminology 41(4):1287–1318. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2003.tb01020.x

Bersani B, Laub J, Nieuwbeerta P (2009) Marriage and desistance from crime in The Netherlands: do gender and socio-historical context matter? J Quant Criminol 25(1):3–24. doi:10.1007/s10940-008-9056-4

Block CR, van der Werff C (1991) Initiation and continuation of a criminal career: who are the most active and dangerous offenders in the Netherlands (105). WODC, Ministerie van Justitie, Den Haag

Blokland AAJ, Nieuwbeerta P (2005) The effects of life circumstances on longitudinal trajectories of offending. Criminology 43(4):1203–1240. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2005.00037.x

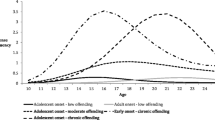

Blokland AAJ, Nagin DS, Nieuwbeerta P (2005) Life span offending trajectories of a Dutch conviction cohort. Criminology 43(4):919–954. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2005.00029.x

Blumstein A, Beck AJ (1999) Population growth in US prisons, 1980–1996. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Clotfelter CT, Cook PJ (1993) The “Gambler’s Fallacy” in lottery play. Manage Sci 39(12):1521–1525. doi:10.1287/mnsc.39.12.1521

Cochran WG (1965) The planning of observational studies of human populations. J R Stat Soc [Ser A] 128:134–156. doi:10.2307/2344179

Council of Europe (2001) Crime and criminal justice in Europe. Council of Europe, Strasbourg

Cullen FT (2002) Rehabilitation and treatment programs. In: Wilson JQ, Petersilia J (eds) Crime public policies for crime control. ICS Press, Oakland, pp 253–611

Dehejia RH, Wahba S (1999) Causal effects in nonexperimental studies: reevaluating the evaluation of training programs. J Am Stat Assoc 94:1053–1062. doi:10.2307/2669919

Drago F, Galbiati R, Vertova P (2008) Prison conditions and recidivism. Working paper. University of Naples Parthenope

Fagan J, Guggenheim M (1996) Preventive detention and the judicial prediction of dangerousness for juveniles: a natural experiment. J Crim Law Criminol 86(2):415–448. doi:10.2307/1144032

Farrington DP (1986) Age and crime. In: Tonry M, Morris N (eds) Crime and justice: an annual review of research. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 189–250

Freeman RB (1996) Why do so many young American men commit crime and what might we do about it? J Econ Perspect 10(1):25–42

Garland D (2001) The culture of control: crime and social order in contemporary society. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Gendreau P, Goggin C, Cullen F (1999) The effects of prison sentences on recidivism. Solicitor General Canada, Ottawa

Gilovich T (1983) Biased evaluation and persistence in gambling. J Pers Soc Psychol 44:1110–1126. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.44.6.1110

Glueck S, Glueck E (1950) Unraveling delinquency. The Commonwealth Fund, New York

Gottfredson DM (1999) Effects of judge’s sentencing decisions on criminal careers. National Institute of Justice: Research in Brief. US Department of Justice, Washington, DC. http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/178889.pdf

Gottfredson MR, Gottfredson DM (1988) Decision making in criminal justice: toward the rational exercise of discretion, 2nd edn. Plenum, New York

Green D, Winik D (2008) The effects of incarceration on recidivism among drug offenders: An experimental approach. Working paper. Yale University

Grove WM, Meehl PE (1996) Comparative efficiency of informal (subjective, impressionistic) and formal (mechanical, algorithmic) prediction procedures: the clinical-statistical controversy. Psychol Public Policy Law 2:293–323. doi:10.1037/1076-8971.2.2.293

Hagan J, Palloni A (1990) The social reproduction of a criminal class in working-class London 1950–1980. Am J Sociol 96:265–299. doi:10.1086/229530

Haviland AM, Nagin DS (2005) Causal inferences with group based trajectory models. Psychometrika 70(3):1–22. doi:10.1007/s11336-004-1261-y

Haviland A, Nagin DS (2007) Using group-based trajectory modeling in conjunction with propensity scores to improve balance. J Exp Criminol 3:65–82. doi:10.1007/s11292-007-9023-3

Haviland A, Nagin DS, Rosenbaum PR (2007) Combining propensity score matching and group-based trajectory modeling in an observational study. Psychol Methods 12:247–267. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.12.3.247

Haviland A, Nagin DS, Rosenbaum PR, Tremblay RE (2008) Combining group-based trajectory modeling and propensity score matching for causal inferences in nonexperimental longitudinal data. Dev Psychol 44(2):422–436

Hawkins G (1976) The prison; policy and practice. Chicago University Press, Chicago

Heckman J, Ichimura H, Smith J, Todd P (1998) Characterizing selection bias using experimental data. Econometrica 66:1017–1098. doi:10.2307/2999630

Helland E, Tabarrok A (2007) Does three strikes deter? a nonparametric estimation. J Hum Resour 42(2):309–330

Joffe MM, Rosenbaum PR (1999) Propensity scores. Am J Epidemiol 150(4):327–333

Johnson B (2003) Racial and ethnic disparities in sentencing departures across modes of conviction. Criminology 41(2):501–542. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2003.tb00994.x

Johnson B (2006) The multilevel context of criminal sentencing: integrating judge and county level influences in the study of courtroom decision making. Criminology 44(2):259–298. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2006.00049.x

Killias M, Aebi M, Ribeaud D (2000) Does community service rehabilitate better than shorter-term imprisonment? Results of a controlled experiment. Howard J Crim Justice 39(1):40–57. doi:10.1111/1468-2311.00152

King RD, Massoglia M, MacMillan R (2007) The context of marriage and crime: gender the propensity to marry, and offending in early adulthood. Criminology 45(1):33–66. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2007.00071.x

Kleiman M, Ostrom BJ, Cheesman FLII (2007) Using risk assessment to inform sentencing decisions for nonviolent offenders in Virginia. Crime Delinq 53(1):106–132. doi:10.1177/0011128706294442

Klepper S, Nagin D (1989) The deterrent effect of perceived certainty and severity of punishment revisited. Criminology 27:721–746. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1989.tb01052.x

Laub JH, Sampson RJ (2003) Shared beginnings, divergent lives: delinquent boys to age 70. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Li YP, Propert KJ, Rosenbaum PR (2001) Balanced risk set matching. J Am Stat Assoc 96:870–882. doi:10.1198/016214501753208573

MacKenzie DL (2002) Reducing the criminal activities of known offenders and delinquents; crime prevention in the courts and corrections. In: Sherman LW, Farrington DP, Welsh BC, MacKenzie DL (eds) Evidence-based crime prevention. Routledge, London, pp 330–404

Manza J, Uggen C (2006) Locked out: Felon disenfranchisement and American democracy. Oxford University Press, New York

Matsueda RL (1992) Reflected appraisal, parental labeling, and delinquency: specifying a symbolic interactionist theory. Am J Sociol 97:1577–1611. doi:10.1086/229940

Mitchell O (2005) A meta-analysis of race and sentencing research: explaining the inconsistencies. J Quant Criminol 21(4):439–466. doi:10.1007/s10940-005-7362-7

Moffitt TE (1993) Life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited anti-social behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev 100:674–701. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.674

Moffitt TE (1994) Natural histories of delinquency. In: Weitekamp EGM, Kerner H-J (eds) Cross-national longitudinal research on human development and criminal behavior. Kluwer, Dordrecht, pp 3–61

Moffitt TE (2006) Life-course persistent versus adolescence-limited antisocial behavior. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ (eds) Developmental psychopathology, vol 3. Wiley, Hoboken, pp 570–598

Monahan J (2006) Structured violence risk assessment. In: Simon R, Tardiff K (eds) American psychiatric publishing textbook on violence assessment and management. American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington

Nagin DS (1998) Criminal deterrence research: a review of the evidence and a research agenda for the outset of the 21st century. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice: an annual review of research. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Nagin DS (1999) Analyzing developmental trajectories: a semi-parametric, group-based approach. Psychol Methods 4:139–177. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.4.2.139

Nagin DS (2004) Response to “Methodological sensitivities to latent class analysis of long-term criminal trajectories”. J Quant Criminol 20:27–35. doi:10.1023/B:JOQC.0000016697.85827.22

Nagin DS (2005) Group-based modeling of development over the life course. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Nagin DS, Cullen FT, Lero Jonson C (2008) Imprisonment and reoffending. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and Justice: a review of research, vol 23. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Nagin DS, Paternoster R (1994) Personal capital and social control: the deterrence of individual differences in criminal offending. Criminology 32(4):581–606. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1994.tb01166.x

Nagin DS, Pogarsky G (2003) An experimental investigation of deterrence: cheating, self-serving bias, & impulsivity. Criminology 41:501–527. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2003.tb00985.x

Nagin D, Waldfogel J (1995) The effects of criminality and conviction on the labor market status of young British offenders. Int Rev Law Econ 15:109–126. doi:10.1016/0144-8188(94)00004-E

Nagin DS, Waldfogel J (1998) The effect of conviction on income through the life cycle. Int Rev Law Econ 18:25–40. doi:10.1016/S0144-8188(97)00055-0

Nagin D, Pagani L, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F (2003) Life course turning points: the effect of grade retention on physical aggression. Dev Psychopathol 15:343–361. doi:10.1017/S0954579403000191

Nieuwbeerta P (2006) Gevangenisstraf, levenslopen en criminele carrieres [Imprisonment, life courses and criminal careers]. Inaugural lecture. Utrecht University, Utrecht

Nieuwbeerta P (2008) Intended and unintended consequences of imprisonment. Research proposal for Dutch National Science Foundations (NWO). NSCR, Leiden

Nieuwbeerta P, Blokland AAJ (2003) Criminal careers of adult Dutch offenders (Codebook and Documentation). NSCR, Leiden

Nieuwbeerta P, Leistra G (2007) Dodelijk geweld. Moord en doodslag in Nederland. Uitgeverij Balans, Amsterdam

Paternoster R, Piquero A (1995) Reconceptualizing deterrence: an empirical test of personal and vicarious experiences. J Res Crime Delinq 32(3):251–286. doi:10.1177/0022427895032003001

Patterson GR, DeBaryshe BD, Ramsy E (1989) A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. Am Psychol 44(2):329–355. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.329

Patterson GR, Forgatch MS, Yoerger KL, Stoolmiller M (1998) Variables that initiate and maintain an early-onset trajectory for juvenile offending. Dev Psychopathol 10:531–547. doi:10.1017/S0954579498001734

Pattillo M, Weiman DF, Western B (2004) Imprisoning America. The social effects of mass incarceration. Russel Sage, New York

Piquero A, Paternoster R (1998) An application of Stafford and Warr’s reconceptualization of deterrence to drinking and driving. J Res Crime Delinq 35(1):3–39. doi:10.1177/0022427898035001001

Pogarsky G, Piquero A (2003) Can punishment encourage offending? Investigating the “resetting” effect. J Res Crime Delinq 40(1):95–120. doi:10.1177/0022427802239255

Rosenbaum P, Rubin D (1983) The central role of propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70:41–55. doi:10.1093/biomet/70.1.41

Rosenbaum P, Rubin D (1984) Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. J Am Stat Assoc 94:516–524. doi:10.2307/2288398

Rosenbaum P, Rubin D (1985) Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am Stat 39:33–38. doi:10.2307/2683903

Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1993) Crime in the making: pathways and turning points through life. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1997) A life course theory of cumulative disadvantage. In: Thornberry TP (ed) Developmental theories of crime and delinquency. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, pp 133–161

Schneider AL (1986) Restitution and recidivism rates of juvenile offenders: results from four experimental studies. Criminology 24(3):533–552. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1986.tb00389.x

Sherman LW (1993) Defiance, deterrence, and irrelevance: a theory of the criminal sanction. J Res Crime Delinq 30(4):445–473. doi:10.1177/0022427893030004006

Smith HL (1997) Matching with multiple controls to estimate treatment effects in observational studies. Sociol Methodol 27:325–353. doi:10.1111/1467-9531.271030

Spohn C (2000) Thirty years of sentencing reform: the quest for a racially neutral sentencing process, National Institute of Justice: Criminal Justice 2000. National Institute of Justice, Washington

Stafford M, Warr M (1993) A reconceptualization of general and specific deterrence. J Res Crime Delinq 30:123–135. doi:10.1177/0022427893030002001

Steffensmeier D, Demuth S (2000) Ethnicity and sentencing outcomes in US Federal Courts: who is punished more harshly? Am Sociol Rev 65(5):705–729. doi:10.2307/2657543

Steffensmeier DJ, Ulmer JT (2005) Confessions of a dying thief. Aldine/Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick

Steffensmeier D, Ulmer J, Kramer J (1998) The interaction of race, gender and age in criminal sentencing: the punishment cost of being young, black, and male. Criminology 36(4):763–798. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1998.tb01265.x

Sweeten G, Apel R (2007) Incapacitation: revisiting an old question with a new method and new data. J Quant Criminol 23(4):303–326. doi:10.1007/s10940-007-9032-4

Swets JA, Dawes RM, Monahan J (2000) Psychological science can improve diagnostic decisions. Psychol Sci Public Interest: J Am Psychol Soc 1:1–26

Tak PJP (2003) The Dutch criminal justice system; organization and operation. WODC, The Hague

Tonry M (2004) Thinking about crime: sense and sensibility in American penal culture. Oxford University Press, New York

Tonry M (ed) (2007) Crime, punishment, and politics in comparative perspective. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

van der Werff C (1979) Speciale Preventie; een Penologisch Onderzoek [Individual Prevention]. PhD Dissertation. University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands

van der Werff C (1986) Recidive 1977; Recidivecijfers van in 1977 wegens misdrijf veroordeelden en niet-vervolgden (67).WODC, Ministerie van Justitie, Den Haag

Van Grinsven V, Bruinsma GJN (1990) Een reconstructie van besluitvorming. De procesmethode geïllustreerd aan straftoemetingsbeslissingen van de rechter [Reconstructing decisions. Illustrating the processmethod by sentencing verdicts]. Beleidswetenschap 2(13):1–148

Vigorita MS (2003) Judicial risk assessment: the impact of risk, stakes, and jurisdiction. Crim Justice Policy Rev 14(3):361–376. doi:10.1177/0887403403253722

Villettaz P, Killias M, Zoder I (2006) The effects of custodial vs. non-custodial sentences on re-offending. A systematic review of the state of knowledge. http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/doc-pdf/Campbell-report-30.09.06.pdf

Von Hirsch A (1987) Past or future crimes: deservedness and dangerousness in the sentencing of criminals. Rutgers, New Brunswick

Waldfogel J (1993) The effect of criminal conviction on income and the trust “reposed in the workmen”. J Hum Resour XXIX(1):62–81

Wermink H, Blokland A, Nieuwbeerta P, Tollenaar N (2009) Recidive na werkstraffen: een gematchte vergelijking [Recidivism after community service: a matched samples comparison]. Tijdschrift voor Criminologie, 51(4) (in print)

Western B (2002) The impact of incarceration on wage mobility and inequality. Am Sociol Rev 67:526–546. doi:10.2307/3088944

Western B (2006) Punishment and inequality in America. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Western B, Kling JR, Weiman DF (2001) The labor market consequences of incarceration. Crime Delinq 47(3):410–427. doi:10.1177/0011128701047003007

Williams KR, Hawkins R (1986) Perceptual research on general deterrence: a critical review. Law Soc Rev 20(4):545–572. doi:10.2307/3053466

WODC (2003) European sourcebook of crime and criminal justice statistics. Boom Legal Publishers, The Hague

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Rosenbaum for many valuable suggestions. All errors, however, remain our own. This work was funded in part by the National Science Foundation (NSF) (SES-99113700; SES-0647576) and the National Institute of Mental Health (RO1 MH65611-01A2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nieuwbeerta, P., Nagin, D.S. & Blokland, A.A.J. Assessing the Impact of First-Time Imprisonment on Offenders’ Subsequent Criminal Career Development: A Matched Samples Comparison. J Quant Criminol 25, 227–257 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-009-9069-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-009-9069-7