Abstract

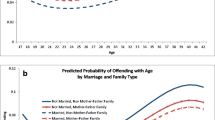

Over the last two decades, research examining desistance from crime in adulthood has steadily increased. The evidence from this body of research consistently demonstrates that salient life events—in particular, marriage—are associated with a reduction of offending across the life course. However, previous studies have been largely limited to male samples in the United States. As a result, questions regarding the universal effect of these relationships remain. Specifically, research is needed to assess whether the desistance effect of life events like marriage varies by gender and/or socio-historical context in countries other than the U.S. The present research addresses these gaps by examining the relationship between marriage and criminal offending using data from the Criminal Career and Life Course Study (CCLS). The CCLS includes criminal conviction histories spanning a large portion of the life course for nearly 5,000 men and women convicted in the Netherlands in 1977. Because we assess change over multiple observations within and between individuals, we utilize hierarchical models to estimate gender and contextual effects of marriage on criminal offending (i.e., any, violent, and property convictions). Overall, we find consistent support for the idea that marriage reduces offending across gender and socio-historical context. Notably, we find that the reduction in the odds of offending due to marriage is significantly greater for individuals in the most contemporary context. The implications of these findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Based on identifying information from 1977, researchers at the NSCR were able to trace 89.4% of the original sample (n = 5,164), leaving a total of 4,615 individuals in the sample to be analyzed. The characteristics of these 4,615 individuals are similar to the total sample consisting of 5,164 persons, and therefore can be regarded as representative of all offenders in 1977. For more information on the full CCLS sample we refer readers to the CCLS codebook (Nieuwbeerta and Blokland 2003) and previous publications based on this dataset (Blokland and Nieuwbeerta 2005; Blokland et al. 2005).

Given the decreasing sample sizes after age 55, we conducted all of our analyses twice: first using data for the full age range (12 thru 79) and second for ages 12–55. Importantly, the substantive results do not differ across the full versus the age restricted sample. However, it should be recognized that using the restricted age means that for 2% of the cases the offense by which they were sampled in 1977 is not included in the analysis. This may potentially bias the estimate of the effect of marriage for that group (but the direction is unclear since it depends on the number of persons married and divorced at that age). Since, the substantive results of the analyses on the full and the age restricted sample are nearly identical and most notably in the analyses on the full age range we find that the good marriage effect is strongest in the most contemporary context/group, we are confident that our results are robust. Thus, to limit the length of this paper we did not present the results of both analyses, but only for the age restricted sample (12 thru 55).

While the GDF contain information on all offenses that have lead to any type of judicial interference, here we use only information on those offenses that were either followed by a conviction or a prosecutorial disposition due to policy reasons, thereby excluding cases that resulted in an acquittal or a prosecutorial disposition due to insufficient evidence.

Unlike birth-cohort studies, the age range in the sample is broad and skewed, ranging from 12 to 79 with a peak at age 18. This feature has two implications. First, the convictions recorded for the sample cover a long period—from 1924 to 2002 (when the data collection period concluded). Second, individuals were not randomly sampled from the entire population; they were all criminally active in 1977.

Given its prevalence in 1977, the sample for driving under the influence was confined to 2%. Less common, serious offenses were over-sampled including: 25% of all robbery, public violence, and battery cases; 100% of all cases involving murder (including attempts), offenses against decency, rape, child molesting, and other sexual assaults; and 17% of all drug offenses. Additionally, because the sample was one of cases, not people, offenders who had two or more convictions in 1977 were more likely to be included in the study. In analyzing the data a weighting factor is included so that the weighted sample represents the distribution of offense types and individuals as they were convicted in 1977.

A reviewer raised a concern that the non-random sampling strategy employed to create the CCLS data may result in substantively different samples across the three groups. Specifically, older individuals in the sample, because they were convicted of a crime in later adulthood (after age 32), are by definition long-term offenders. Therefore, the older group may capture more criminally active individuals while the younger group may be more representative of the general population in regards to their level of criminal activity. We agree that this concern is an important one and may influence the findings from our analysis. However, it is crucial to keep in mind two points. First, the inclusion criterion for this sample was a conviction for any offense. Thus, individuals may be in the sample because of a violent or property offense or they may be in the sample due to a drunk driving or a public order offense. Seriousness of the offense in 1977 was not used for inclusion in the sample. In fact, examining a variety of descriptive factors, we find that the youngest group has a significantly earlier age of onset and they are more likely to be convicted of a serious offense. Second, previous analyses with these data (see Blokland et al. 2005:940) indicate that the youngest group remains as active—if not more so—than the older group, across the life course.

Although the traditional estimation strategy for hierarchical non-linear models has been the use of penalized quasi-likelihood (PQL), we utilize Laplace estimation as it has been shown to provide more precise estimates (Raudenbush et al. 2000; Snijders and Bosker 1999). Additionally, the Laplace estimation method produces a model fit statistic (deviance) which is not available with PQL. We also conducted analyses using the frequency of criminal convictions. Because of the relative rarity of a criminal conviction in each age-period, the rarity of multiple convictions in a given year, and because the substantive results did not differ, we chose to report the estimates from the logit model.

Age, age2, and age3 are divided by 10 (for ease in estimation) and are grand mean centered.

We include a random age linear slope in the model for any conviction. The model indicated that a random age linear slope was not significant for both the violent conviction and property conviction analyses. Therefore, we assume a fixed effect for age in these models. The inclusion of error terms for the age2 and age3 parameters did not allow the model to converge.

The descriptive patterns presented for the full sample maintain for gender and socio-historical context specific samples. These tables are available upon request from the lead author.

Tables for the sensitivity analyses are available from the lead author upon request.

The equation for this model is: \( \pi _{4} = \beta _{{40}} + \beta _{{41}} (female) + \beta _{{42}} (group2) + \beta _{{43}} (group3) + \beta _{{44}} (female) \times (group2) + \beta _{{45}} (female) \times (group3) \)

References

Alwin DF, McCammon RJ (2004) Generations, cohorts, and social change. In: Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ (eds) Handbook of the life course. Springer, New York, NY, pp 23–49

Baskin DR, Sommers IB (1998) Casualties of community disorder: women’s careers in violent crime. Westview Press, Boulder, CO

Bianchi SM, Casper LM, King RB (2005) Work, family, health and well-being. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ

Bijleveld CCJ, Smit PR (2005) Crime and punishment in the Netherlands, 1980–1999. In: Tonry M, Farrington DP (eds) Crime and punishment in western countries, 1980–1999. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, pp 161–212

Black DJ (1970) The production of crime rates. Am Sociol Rev 35:733–748

Blokland AAJ, Nieuwbeerta P (2005) The effects of life circumstances on longitudinal trajectories of offending. Criminology 43:1203–1240

Blokland AAJ, Nagin DS, Nieuwbeerta P (2005) Life span offending trajectories of a Dutch conviction cohort. Criminology 43:919–954

Daly K (1987) Discrimination in the criminal courts: family, gender, and the problem of equal treatment. Soc Forces 66:152–175

Daly K, Tonry M (1997) Gender, race, and sentencing. Crime Justice 22:201–252

Edin K, Nelson TJ, Paranal R (2004) Fatherhood and incarceration as potential turning points in the criminal careers of unskilled men. In: Patillo M, Weiman D, Western B (eds) Imprisoning America: the social effects of mass incarceration. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, NY, pp 46–75

Eggleston EP, Laub JH, Sampson RJ (2004) Methodological sensitivities to latent class analysis of long-term criminal trajectories. J Quant Criminol 20:1–26

Elder GH Jr (1975) Age differentiation and the life course. Annu Rev Sociol 1:165–190

Farrington DP (1999) A criminological research agenda for the next millennium. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 43:154–167

Farrington DP, Maughan B (1999) Criminal careers in two London cohorts. Crim Behav Men Health 9:91–106

Farrington DP, West DJ (1995) Effects of marriage, separation, and children on offending by adult males. In: Blau ZS, Hagan J (eds) Current perspectives on aging and the life cycle: delinquency and disrepute in the life course, vol 4. JAI Press Inc., Greenwich, CT, pp 249–281

Giordano PC, Cernkovich SA, Rudolph JL (2002) Gender, crime, and desistance: toward a theory of cognitive transformation. Am J Sociol 107:990–1064

Giordano PC, Deines JA, Cernkovich SA (2006) In and out of crime: a life course perspective on girls’ delinquency. In: Heimer K, Kruttschnitt C (eds) Gender and crime: patterns in victimization and offending. New York University Press, New York, NY, pp 17–40

Gove WR, Hughes M, Geerken M (1985) Are Uniform Crime Reports a valid indicator of the index crimes? An affirmative answer with minor qualifications. Criminology 23:451–501

Graham J, Bowling B (1996) Young people and crime. Home Office Research Study 145, London

Hagestad GO, Call VRA (2007) Pathways to childlessness: a life course perspective. J Fam Issues 28:1338–1361

Hindelang MJ, Hirschi T, Weis JG (1979) Correlates of delinquency: the illusion of discrepancy between self-report and official measures. Am Sociol Rev 44:995–1014

Hogan DP, Astone NM (1986) The transition to adulthood. Annu Rev Sociol 12:109–130

Horney JD, Osgood W, Marshall IH (1995) Criminal careers in the short term: intra-individual variability in crime and its relation to local life circumstances. Am Sociol Rev 60:655–673

Kiernan K (2004) Unmarried cohabitation and parenthood in Britain and Europe. Law Policy 26:33–55

King RD, Massoglia M, MacMillan R (2007) The context of marriage and crime: gender, the propensity to marry, and offending in early adulthood. Criminology 45:33–65

Knight BJ, Osborn SG, West DJ (1977) Early marriage and criminal tendency in males. Brit J Criminol 17:348–360

Kruttschnitt C (1982) Women, crime, and dependency: an application of the theory of law. Criminology 19:495–513

Laub JH, Sampson RJ (2003) Shared beginnings, divergent lives: delinquent boys to age 70. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Laub JH (1999) Alterations in the opportunity structure: a criminological perspective. In: Booth A, Crouter A, Shanahan M (eds) Transitions to adulthood in a changing economy: no work. No Family, No Future, Praeger Publishers, Westport, CT, pp 48–55

Laub JH, Sampson RJ (1995) Crime and context in the lives of 1,000 Boston men, circa 1925–1955. In: Blau ZS, Hagan J (eds) Current perspectives on aging and the life cycle: delinquency and disrepute in the life course, vol 4. JAI Press Inc., Greenwich, CT, pp 119–139

Leverentz AM (2006) The love of a good man? Romantic relationships as a source of support or hindrance for female ex-offenders. J Res Crime Delinq 43:459–488

Liefbroer AC, Dykstra PA (2000) Samenleven met een partner [Living together with a partner]. In Liefbroer AC, Dykstra PA (eds) Levenslopen in Verandering. Een studie naar ontwikkelingen in de levenslopen van Nederlanders geboren tussen 1900 and 1970. [Changes over the life course. A study of the developments in life courses of the Dutch between 1900 and 1970.], SDU Publishers, The Hague

Loeber R, Le Blanc M (1990) Toward a developmental criminology. Crime Justice 12:375–473

Mannheim K (1952) Essays on the sociology of knowledge. Routledge & Kegan Paul LTD, London

Manting D (1996) The changing meaning of cohabitation and marriage. Eur Sociol Rev 12:53–65

Massoglia M, Uggen C (2007) Subjective desistance and the transition to adulthood. J Contemp Crim Justice 23:90–103

Maume MO, Ousey GC, Beaver K (2005) Cutting the grass: a reexamination of the link between marital attachment, delinquent peers, and desistance from marijuana use. J Quant Criminol 21:27–53

Mills M (2004) Stability and change: the structuration of partnership histories in Canada, the Netherlands, and the Russian Federation. Eur J Popul 20:141–175

Mensch B, Singh S, Casterline JB (2005) Trends in the timing of first marriage among men and women in the developing world. The Population Research Council, Inc., New York, NY

Nieuwbeerta P, Blokland AAJ (2003) Criminal careers and adult dutch offenders (codebook and documentation). Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement, Leiden

Oppenheimer VK (1994) Women’s rising employment and the future of the family in industrial societies. Popul Dev Rev 20:293–342

Osgood WD (2005) Life events and criminal behaviour. Paper presented at the Second Annual SCoPiC Conference, June, Cambridge, UK

Ouimet M, Le Blanc M (1996) The role of life experiences in the continuation of the adult criminal career. Crim Behav Men Health 6:73–97

Piquero AR, Blumstein A, Brame R, Haapanen R, Mulvey EP, Nagin DS (2001) Assessing the impact of exposure time and incapacitation on longitudinal trajectories of criminal offending. J Adolescent Res 16:54–74

Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS (2002) Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Raudenbush SW, Yang M, Yosef M (2000) Maximum likelihood for generalized linear models with nested random effects via high-order multivariate laplace approximation. J Comput Graph Stat 9:141–157

Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Congdon R (2007) HLM 6.04: hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Scientific Software International, Lincolnwood, IL

Riley MW (1973) Aging and cohort succession: interpretations and misinterpretations. Public Opin Quart 37:35–49

Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1993) Crime in the making: pathways and turning points through life. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Sampson RJ, Laub JH, Wimer C (2006) Does marriage reduce crime? A counterfactual approach to within-individual causal effects. Criminology 44:465–508

Shanahan MJ (2000) Pathways to adulthood in changing societies: variability and mechanisms in life course perspective. Annu Rev Sociol 26:667–692

Smock PJ (2000) Cohabitation in the United States: an appraisal of research themes, findings, and implications. Annu Rev Sociol 26:1–20

Snijders T, Bosker R (1999) Multilevel analysis: an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Steffensmeier D, Allan E (1996) Gender and crime: toward a gendered theory of female offending. Annu Rev Sociol 22:459–487

Steffensmeier D, Kramer J, Streifel C (1993) Gender and imprisonment decisions. Criminology 31:411–446

Uggen C (2000) Work as a turning point in the life course of criminals: a duration model of age, employment, and recidivism. Am Sociol Rev 67:529–546

Uggen C, Kruttschnitt C (1998) Crime in the breaking: gender differences in desistance. Law Soc Rev 32:339–366

van Zanden JL (1998) The economic history of the Netherlands 1914–1995: a small open economy in the ‘long’ twentieth century. Routledge, London, UK

Waite LJ (1995) Does marriage matter? Demography 32:483–507

Waite LJ, Gallagher M (2000) The case for marriage: why married people are happier, healthier and better off financially. Random House, Inc., New York, NY

Warr M (1998) Life-course transitions and desistance from crime. Criminology 34:183–216

Wilson WJ (1987) The truly disadvantaged: the inner city, the underclass and public policy. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Wayne Osgood, David Kirk, and Terceira Berdahl for their comments on an earlier version of this paper. In addition, the authors thank the editor of JQC and the three reviewers for their helpful comments and assistance in improving the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bersani, B.E., Laub, J.H. & Nieuwbeerta, P. Marriage and Desistance from Crime in the Netherlands: Do Gender and Socio-Historical Context Matter?. J Quant Criminol 25, 3–24 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-008-9056-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-008-9056-4