Abstract

Background

In healthy BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy (BRRM) strongly reduces the risk of developing breast cancer (BC); however, no clear survival benefit of BRRM over BC surveillance has been reported yet.

Methods

In this Dutch multicenter cohort study, we used multivariable Cox models with BRRM as a time-dependent covariable to estimate the associations between BRRM and the overall and BC-specific mortality rates, separately for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers.

Results

During a mean follow-up of 10.3 years, 722 out of 1712 BRCA1 (42%) and 406 out of 1145 BRCA2 (35%) mutation carriers underwent BRRM. For BRCA1 mutation carriers, we observed 52 deaths (20 from BC) in the surveillance group, and 10 deaths (one from BC) after BRRM. The hazard ratios were 0.40 (95% CI 0.20–0.90) for overall mortality and 0.06 (95% CI 0.01–0.46) for BC-specific mortality. BC-specific survival at age 65 was 93% for surveillance and 99.7% for BRRM. For BRCA2 mutation carriers, we observed 29 deaths (7 from BC) in the surveillance group, and 4 deaths (no BC) after BRRM. The hazard ratio for overall mortality was 0.45 (95% CI 0.15–1.36). BC-specific survival at age 65 was 98% for surveillance and 100% for BRRM.

Conclusion

BRRM was associated with lower mortality than surveillance for BRCA1 mutation carriers, but for BRCA2 mutation carriers, BRRM may lead to similar BC-specific survival as surveillance. Our findings support a more individualized counseling based on BRCA mutation type.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Women with a germline BRCA1/2 gene mutation have high risks of developing breast cancer (BC), estimated to range from 45 to 88% for a first BC up to the age of 70 years [1,2,3,4]. Moreover, BC is diagnosed at a younger age in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers than in the general population [4,5,6], with an increased risk from the age of 25 years. For healthy BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, the options are to follow a BC surveillance program aimed at early BC detection, or to opt for bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy (BRRM) to reduce BC risk. In healthy BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, BRRM reduces the risk of BC with estimates even up to 100% [7,8,9,10,11,12], and this method may have beneficial effects on quality of life by diminishing the strong anxiety of getting BC. However, despite the strong BC risk-reduction, no clear survival benefit of BRRM over BC surveillance has been reported so far.

Mathematical models with simulated cohorts suggested that surveillance with both mammography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in combination with risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy might offer an almost comparable survival as BRRM with risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, due to improved imaging techniques and better systemic treatment options in recent years [13,14,15]. However, no convincing prospective data are available so far. Previously, we observed better 10-year overall survival in the BRRM group than in the surveillance group (99% vs. 96%) among 570 healthy BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, but this difference was not significant [10].

To investigate whether BRRM leads to survival benefit, we determined the overall and breast cancer-specific mortality rates among 2857 healthy BRCA1/2 mutation carriers opting for either BRRM or surveillance with follow-up until 2017. Since BRCA2-associated BCs have more favorable characteristics than BRCA1-associated BCs [10, 16, 17], and BRCA2 mutation carriers have shown lower recurrence rates than BRCA1 mutation carriers [10], we performed all analyses for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers separately.

Participants and methods

Study population

In the context of the Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Netherlands (HEBON) study, members of breast and/or ovarian cancer families are being identified through the departments of Clinical Genetics/Family Cancer Clinics at eight Dutch academic centers and the Netherlands Cancer Institute [18]. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant, or from a close relative in case of already deceased individuals. As of January 1999, relevant data on participants, including data on preventive strategies, the occurrence of cancer and vital status, were retrieved and updated through medical files and questionnaires, and through linkages to the Netherlands Cancer Registry, the Dutch Pathology Database, and the municipal registry database. The latest follow-up date was December 31, 2016. The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committees of all participating centers.

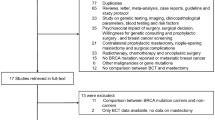

From this national cohort, we identified 5889 germline BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Women were eligible for the study if they had no history of cancer—to avoid cancer-induced testing bias [19, 20]—and had both breasts and both ovaries in situ at the date of DNA test result. As shown in Fig. 1a, we selected 1712 BRCA1 and 1145 BRCA2 mutation carriers.

Flowchart of inclusion of participants (a) and Design of the analytic method and allocation of person-years of observation (b). DNA date of DNA test result, CE censoring event, BRRM bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy, BC first breast cancer. As visualized in b, observation started at the age at DNA test result, or age 25, whichever came last. For women not opting for BRRM, we allocated all person-years of observation (PYO) to the surveillance group (solid lines; scenarios 1, 3, 4, 7). For women opting for BRRM, we allocated PYO before surgery to the surveillance group, and PYO after surgery to the BRRM group (dashed lines; scenarios 2, 5, 6, and 8). The observation ended on the age of death (any cause), or age at study closing date (i.e., December 31, 2016), whichever came first

Data collection

We retrieved data on type of mutation (i.e., BRCA1 or BRCA2) and date of DNA diagnosis; dates of birth, of diagnoses of first BC, ovarian cancer, and other cancers; dates of BRRM and risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy; and date and cause of death. We also collected data on BC characteristics (size, nodal status, behavior, differentiation grade, hormone receptor status, and HER2 status) and BC treatment details.

Breast cancer surveillance for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers in the Netherlands

BC surveillance for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers consisted of annual imaging by MRI between 25 and 60 years (since 1998), next to annual imaging by mammography from 30 till 60 years of age, biennial (annual since 2012) mammography from age 60 till age 75, and annual clinical breast examination from the age of 25 years onward [21]. For the current cohort, the actual attendance to the surveillance program was derived from self-reported data.

Statistical analyses

We evaluated person characteristics by comparing women who opted for BRRM (BRRM group) with women who did not until the end of follow-up (surveillance group). Differences between the BRRM and the surveillance group were tested by using χ2 for categorical variables, and the two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann–Whitney) test for continuous variables.

The outcomes, overall mortality and breast cancer-specific mortality, were measured in person-years of observation. We started the observation period at the age at DNA test result or 25 years of age (since from this age regular BC surveillance is offered to Dutch BRCA1/2 mutation carriers), whichever came last. Figure 1b depicts the allocation of person-years of observation to the BRRM and the surveillance group. For women who opted for BRRM and had unexpected malignant findings in the mastectomy specimens, we considered BC as being developed before BRRM, and therefore we allocated all person-years of observation to the surveillance group. The observation period ended at the age at last follow-up or death (due to all causes for the overall survival analyses and from BC for the breast cancer-specific analyses). The earliest date of DNA result was January 3, 1995.

To estimate the associations between BRRM and survival endpoints, we used extended Cox models with BRRM as a time-dependent variable to obtain hazard ratios (HRs) and accompanying 95% confidence intervals (CIs), using the surveillance group as the reference. To adjust for potential confounders, we generated a propensity score, based on year of birth, age at start of observation, age at DNA test result, year of DNA test result, and undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (yes or no; time dependent) and performed multivariable analyses with the propensity score as covariable. For the mentioned variables all data were available for all participants. To graph the cumulative survival curves for the BRRM and the surveillance group, we used the Simon and Makuch method—which takes into account the change in an individual’s covariate status over time—with chronological age as the time variable [22, 23]. Using the log-rank test for equality of survivor functions, we tested whether the curves were significantly different from each other. We performed all analyses separately for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers.

All P values were two-sided, and a significance level α = 0.05 was used. Analyses were performed using STATA (version 14.1, StataCorp, Collegestation, TX).

Results

Study population

Of the 1712 selected BRCA1 mutation carriers, 722 opted for BRRM, and 406 of the 1145 BRCA2 mutation carriers opted for BRRM (Table 1). Women opting for BRRM underwent DNA testing at a younger age than women who stayed under surveillance until end of follow-up (median age 34 vs. 38 for BRCA1, and 36 vs. 42 for BRCA2 mutation carriers). Also, women in the BRRM group more often opted for risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy than women in the surveillance group [557 (77%) vs. 569 (57%) for BRCA1, and 293 (72%) vs. 441 (60%) for BRCA2 mutation carriers] at a younger age (median age 40 vs. 44 for BRCA1, and 42 vs. 47 for BRCA2 mutation carriers; Table 1).

Breast cancer

BC occurrence (including both invasive and ductal carcinoma in situ) was lower in the BRRM than in the surveillance group [8 (1%) vs. 268 (27%) for BRCA1, and 0 (0%) vs. 144 (19%) for BRCA2 mutation carriers; Table 1]. Among BRCA1 mutation carriers, we observed no differences in tumor characteristics of BCs occurring after BRRM and during surveillance (see Supplementary Table S1).

As shown in Table 2, BRCA2-associated BCs were diagnosed with more favorable characteristics than BRCA1-associated BCs, i.e., diagnosed at older age, more often in situ, better differentiated, and less often showing a triple-negative phenotype. Consequently, BRCA2 mutation carriers were less often treated with chemotherapy, and more often treated with endocrine therapy.

Overall mortality

All-cause mortality rates were lower for women opting for BRRM than for women under surveillance (Table 3). For BRCA1 mutation carriers, the multivariable Cox model yielded an HR of 0.40 (95% CI 0.20–0.80) in favor of the BRRM group. The unadjusted survival curves showed a probability of being alive at 65 years of 93% for the BRRM group and 83% for the surveillance group (Fig. 2a). For BRCA2 mutation carriers, the multivariable HR was 0.45 (95% CI 0.15–1.36) (Table 3), and the probability of being alive at the age of 65 was 93% the BRRM group, and 90% for the surveillance group (Fig. 2b).

Overall survival curves for BRCA1 (a) and BRCA2 (b) mutation carriers and breast cancer-specific survival curves for BRCA1 (c) and BRCA2 (d) mutation carriers opting for bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy (BRRM) versus staying under surveillance, using the Simon and Makuch method—which takes into account the change in an individual’s variable status over time—with chronological age as the time variable

Breast cancer-specific mortality

Breast cancer-specific mortality rates were lower for women opting for BRRM than for women under surveillance (Table 3). Eventually, one BRCA1 (0.1%) and no BRCA2 mutation carriers died due to BC after BRRM, while from the surveillance group 20 BRCA1 (2.0%) and 7 BRCA2 (0.9%) mutation carriers died due to BC. For BRCA1 mutation carriers, the multivariable HR was 0.06 (95% CI 0.01–0.46) in favor of the BRRM group. At the age of 65, the probability of not having died due to BC was 99.7% for the BRRM group and 93% for the surveillance group (Fig. 2c). For BRCA2 mutation carriers, no HR could be estimated, as not one woman opting for BRRM died due to BC (Table 3). The probability of not having died due to BC at the age of 65 was 100% in the BRRM and 98% in the surveillance group (Fig. 2d).

Discussion

In this nationwide cohort study, we observed lower overall and breast cancer-specific mortality rates among BRCA1 mutation carriers opting for BRRM than among those under surveillance. For BRCA2 mutation carriers, BRRM was nonsignificantly associated with lower overall mortality when compared with surveillance. Not one BRCA2 mutation carrier died of BC after BRRM, while the surveillance group performed almost as good. In addition, BRCA2-associated BCs were diagnosed less frequently, and had more favorable characteristics than BRCA1-associated BCs.

All analyses were performed separately for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, which is more accurate because BRCA1-associated BCs and BRCA2-associated BCs represent different entities. The current results are in line with our previous observation of a small but nonsignificant better 10-year overall survival after BRRM than under surveillance (99% vs. 96%) for a smaller combined cohort of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers [10]. The observation that BRRM was associated with lower breast cancer-specific mortality for BRCA1 mutation carriers, and not for BRCA2 mutation carriers underscores that counseling for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers regarding the choice between risk-reducing mastectomy and surveillance might be tailored, although confirmation in a larger cohort of especially BRCA2 mutation carriers is warranted.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first cohort study comparing BRRM with surveillance with respect to survival in healthy BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers separately. Previous investigations have shown that BRRM effectively reduces BC risk [7,8,9,10,11,12, 24, 25], but convincing data regarding survival after BRRM in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers are scarce and mainly derived from modeling studies. Using a simulated cohort and Markov modeling of outcomes, Grann et al. estimated that BRRM plus risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy at the age of 30 may extend survival by 4.9 years over surveillance alone [26]. Further, Sigal et al. yielded from their Monte Carlo simulation model gains in life expectancy after BRRM plus risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy varying from 6.8 to 10.3 for BRCA1 and 3.4 to 4.4 years for BRCA2 mutation carriers [15]. Recently, Giannakeas and Narod showed in a simulated cohort that for BRCA mutation carriers who underwent bilateral mastectomy at the age of 25, the probability of being alive at age 80 increased by 8.7% [27]. In addition, in an exploratory study in unaffected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers and untested female first-degree relatives, Ingham et al. showed overall survival benefit of ~ 10% after risk-reducing surgery [28]. However, this study is not directly comparable to the current study since the authors compared three groups of women undergoing risk-reducing surgery (i.e., BRRM only, risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy only, or both) with women without any surgery, while we currently incorporated undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (yes/no) in the model. In our opinion, this better reflects daily practice: as a result of directive counseling due to ineffective screening protocols for early ovarian cancer detection, the uptake of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy is high for both women undergoing BRRM (~ 75%) and women not (yet) opting for BRRM (~ 60%).

For BRCA1 mutation carriers under surveillance, BC and ovarian cancer were the main causes of death. The high percentage of ovarian cancer deaths in this group—which was similar to that of BC deaths—emphasizes the need for RRSO for BRCA mutation carriers. While in the surveillance group 20 out of 990 women (2.0%) died due to BC, only one out of 722 women (0.1%) died from BC after BRRM. The latter patient was identified with a BRCA1 mutation at the age of 38, and underwent BRRM 1 year later (in 2007). At the age of 42, she was diagnosed with a triple-negative BC with lung metastases, and died 1 year later. This emphasizes—in addition to the fact that eight BCs occurred 4.4 median years after BRRM in the current cohort—that BRRM does not fully protect against the occurrence of BC and BC-related death.

Of the 29 deceased BRCA2 mutation carriers in the surveillance group, 24% died of BC, 59% of another malignancy—including two deaths due to ovarian cancer and seven due to pancreatic cancer—and 17% died of nonmalignancy-related causes. The higher numbers of non BC-related deaths in the surveillance group seem to be coincidental, but may explain the higher overall mortality rate though comparable breast cancer-specific mortality rate among BRCA2 mutation carriers under surveillance.

In BRCA2 mutation carriers, we observed no BCs and no BC-related deaths after BRRM versus 144 BC cases and seven BC-related deaths in the surveillance group, suggesting a maximal risk-reduction of developing BC and dying due to BC after BRRM. However, the absolute breast cancer-specific survival benefit at the age of 65 was minimal (2%), partly due to the low BC-specific mortality in the surveillance group (i.e., 0.9 per 1000 person-years of observation). The latter can be explained by the observation that BRCA2-associated BCs were diagnosed with more favorable characteristics, i.e., diagnosed at older age, more often in situ, better differentiated, and less often showing a triple-negative phenotype—than BRCA1-associated BCs. This supports previous suggestions that BRCA2-associated BC patients face a better prognosis than BRCA1-associated BC patients [10, 16]. The current results suggest that regarding breast cancer-specific mortality, BC surveillance may be a reasonable and balanced alternative to BRRM for BRCA2 mutation carriers.

The main strengths of the current study are (1) the sufficient numbers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers allowing analyses for both groups separately, (2) with long enough follow-up, and (3) the availability of data on cause of death, enabling to specifically address the ultimate goal for BRRM, i.e., breast cancer-specific survival.

This study also has limitations. First, information regarding BC screening modality and frequency was derived from self-reported data, and unknown for ~ 50% of the women in the surveillance groups. However, we do know that all women had been counseled by clinical geneticists and were aware of an identified BRCA mutation at the start of the observation period. Therefore, we assume that the vast majority of the women did participate in a BC surveillance program for high-risk women according to Dutch guidelines. This assumption is supported by the experience from the Rotterdam Family Cancer Clinic that after being positively tested for a pathologic mutation in one of the BRCA genes, 97% of the mutation carriers is yearly screened; 79% of the mutation carriers are yearly screened by both MRI and mammography, 11% by MRI only (aged < 30 years), and 7% by mammography only (aged > 60 years). Only three percent of the proven mutation carriers seem not to attend the national screening program for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, or are screened in another hospital (unpublished data). These numbers are in line with recently reported international trends in the uptake of cancer screening among BRCA1/2 mutation carriers [29].

Still, if the BC patients with unknown screening status were not under BC surveillance, BCs consequently would be diagnosed at a more advanced stage with worse prognosis. As a result, the observed number of BC-related deaths in the surveillance group could be an overestimation of the actual number of BC-related deaths under surveillance, and a potential breast cancer-specific survival benefit may be overestimated. However, BCs occurring among BRCA1/2 mutation carriers in the surveillance group with unknown screening status showed in fact slightly more favorable characteristics (i.e., more often in situ and smaller than two centimeters; see Supplementary Table S2) than the patients with known screening status. In addition, the absolute number of women dying from BC was lower among the women with unknown screening status: 8 out 864 (0.9%) versus 19 out of 865 (2.2%) among the women with known screening status (P value 0.033; Supplementary Table S2). Thus, it seems plausible that the majority of the women with unknown screening status were actually under BC surveillance, and an overestimation of the observed breast cancer-specific survival is unlikely.

A second limitation may be that family history is not available for all participants. If all women from families with high risks of developing BC—usually at young age—opt for BRRM, this may lead to an overrepresentation of women with lower family-based BC risks in the surveillance groups. Subsequently, the baseline BC risk and following BC-specific mortality may be underestimated in the surveillance groups, leading to an underestimation of potential survival benefit after BRRM. However, despite this potential underestimation, the study found an association with better breast cancer-specific survival for BRCA1 mutation carriers after BRRM. Still, as the influence of family history cannot be ruled out, it will be interesting to take family history into account in future studies.

Thirdly, there might be some bias toward BRRM being offered more often to healthier women. This could be supported by the fact that BRCA2 mutation carriers in the surveillance group show more other cancers (i.e., no BC or ovarian cancer) than those in the BRRM group (9% vs. 6%, P = 0.048; Table 1). However, we did not observe this difference for BRCA1 mutation carriers, where the incidence of other tumors was 7% for both groups. In addition, the median age at diagnosis of cancer other than BC or ovarian cancer is higher in the surveillance group than in the BRRM group (both for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers), suggesting that with longer follow-up—and thus growing age—the numbers of patients with other tumors could increase. Unfortunately, data about health-related issues such as weight and past and current smoking habits are not available for the current cohort.

In conclusion, BRRM was associated with lower overall and breast cancer-specific mortality rates than surveillance for BRCA1 mutation carriers. For BRCA2 mutation carriers, BRRM may lead to similar breast cancer-specific survival as surveillance. The latter is most probably due to the more favorable characteristics of BRCA2-associated BCs. Therefore, for BRCA2 mutation carriers BC surveillance may be as effective as BRRM regarding breast cancer-specific survival. Although the number of events are small—especially for the analyses on breast cancer-specific mortality—our findings may support a more individualized counseling based on BRCA mutation type regarding the difficult choice between BRRM and BC surveillance.

References

van der Kolk DM, de Bock GH, Leegte BK, Schaapveld M, Mourits MJ, de Vries J, van der Hout AH, Oosterwijk JC (2010) Penetrance of breast cancer, ovarian cancer and contralateral breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 families: high cancer incidence at older age. Breast Cancer Res Treat 124(3):643–651

Mavaddat N, Peock S, Frost D, Ellis S, Platte R, Fineberg E, Evans DG, Izatt L, Eeles RA, Adlard J, Davidson R, Eccles D, Cole T, Cook J, Brewer C, Tischkowitz M, Douglas F, Hodgson S, Walker L, Porteous ME, Morrison PJ, Side LE, Kennedy MJ, Houghton C, Donaldson A, Rogers MT, Dorkins H, Miedzybrodzka Z, Gregory H, Eason J, Barwell J, McCann E, Murray A, Antoniou AC, Easton DF, Embrace (2013) Cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from prospective analysis of EMBRACE. J Natl Cancer Inst 105(11):812–822

Brohet RM, Velthuizen ME, Hogervorst FBL, Meijers-Heijboer HEJ, Seynaeve C, Collee MJ, Verhoef S, Ausems MGEM, Hoogerbrugge N, van Asperen CJ, Garcia EG, Menko F, Oosterwijk JC, Devilee P, van’t Veer LJ, van Leeuwen FE, Easton DF, Rookus MA, Antoniou AC, Resource H (2014) Breast and ovarian cancer risks in a large series of clinically ascertained families with a high proportion of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Dutch founder mutations. J Med Genet 51(2):98–107

Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, Phillips KA, Mooij TM, Roos-Blom MJ, Jervis S, van Leeuwen FE, Milne RL, Andrieu N, Goldgar DE, Terry MB, Rookus MA, Easton DF, Antoniou AC, Brca, Consortium BC, McGuffog L, Evans DG, Barrowdale D, Frost D, Adlard J, Ong KR, Izatt L, Tischkowitz M, Eeles R, Davidson R, Hodgson S, Ellis S, Nogues C, Lasset C, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Fricker JP, Faivre L, Berthet P, Hooning MJ, van der Kolk LE, Kets CM, Adank MA, John EM, Chung WK, Andrulis IL, Southey M, Daly MB, Buys SS, Osorio A, Engel C, Kast K, Schmutzler RK, Caldes T, Jakubowska A, Simard J, Friedlander ML, McLachlan SA, Machackova E, Foretova L, Tan YY, Singer CF, Olah E, Gerdes AM, Arver B, Olsson H (2017) Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. JAMA 317(23):2402–2416

Chen S, Parmigiani G (2007) Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J Clin Oncol 25(11):1329–1333

Antoniou AC, Pharoah P, Narod SA, Risch H, Eyfjord J, Hopper J, Loman N, Olsson H, Johansson O, Borg A, Pasini B, Radice P, Manoukian S, Eccles D, Tang N, Olah E, Anton-Culver H, Warner E, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, Gorski B, Tulinius H, Thorlacius S, Eerola H, Nevanlinna H, Syrjakoski K, Kallioniemi O-P, Thompson D, Evans C, Peto J, Lalloo F, Evans DGR, Easton D (2003) Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet 72(5):1117–1130

Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Schaid DJ, Frank TS, Soderberg CL, Sitta DL, Frost MH, Grant CS, Donohue JH, Woods JE, McDonnell SK, Vockley CW, Deffenbaugh A, Couch FJ, Jenkins RB (2001) Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 93(21):1633–1637

Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Lynch HT, Neuhausen SL, van ‘t Veer LJ, Garber JE, Evans GR, Narod SA, Isaacs C, Matloff E, Daly MB, Olopade OI, Weber BL (2004) Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy reduces breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol 22(6):1055–1062

Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Singer CF, Evans DG, Lynch HT, Isaacs C, Garber JE, Neuhausen SL, Matloff E, Eeles R, Pichert G, Van T’veer L, Tung N, Weitzel JN, Couch FJ, Rubinstein WS, Ganz PA, Daly MB, Olopade OI, Tomlinson G, Schildkraut J, Blum JL, Rebbeck TR (2010) Association of risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers with cancer risk and mortality. J Am Med Assoc 304(9):967–975

Heemskerk-Gerritsen BAM, Menke-Pluijmers MBE, Jager A, Tilanus-Linthorst MMA, Koppert LB, Obdeijn IMA, van Deurzen CHM, Collee JM, Seynaeve C, Hooning MJ (2013) Substantial breast cancer risk reduction and potential survival benefit after bilateral mastectomy when compared with surveillance in healthy BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: a prospective analysis. Ann Oncol 24(8):2029–2035

Alaofi R, Nassif M, Al-Hajeili M (2018) Prophylactic mastectomy for the prevention of breast cancer: review of the literature. Avicenna J Med 8(3):67–77

Carbine NE, Lostumbo L, Wallace J, Ko H (2018) Risk-reducing mastectomy for the prevention of primary breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD002748

Kurian AW, Sigal BM, Plevritis SK (2010) Survival analysis of cancer risk reduction strategies for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol 28(2):222–231

Kurian AW, Munoz DF, Rust P, Schackmann EA, Smith M, Clarke L, Mills MA, Plevritis SK (2012) Online tool to guide decisions for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol 30(5):497–506

Sigal BM, Munoz DF, Kurian AW, Plevritis SK (2012) A simulation model to predict the impact of prophylactic surgery and screening on the life expectancy of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 21(7):1066–1077

Brekelmans CT, Tilanus-Linthorst MM, Seynaeve C, vd Ouweland A, Menke-Pluymers MB, Bartels CC, Kriege M, van Geel AN, Burger CW, Eggermont AM, Meijers-Heijboer H, Klijn JG (2007) Tumour characteristics, survival and prognostic factors of hereditary breast cancer from BRCA2-, BRCA1- and non-BRCA1/2 families as compared to sporadic breast cancer cases. Eur J Cancer 43(5):867–876

Lakhani SR, van de Vijver MJ, Jacquemier J, Anderson TJ, Osin PP, McGuffog L, Easton DF, Consortium BCL (2002) The pathology of familial breast cancer: predictive value of immunohistochemical markers estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, HER-2, and p53 in patients with mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. J Clin Oncol 20(9):2310–2318

Pijpe A, Manders P, Brohet RM, Collee JM, Verhoef S, Vasen HFA, Hoogerbrugge N, van Asperen CJ, Dommering C, Ausems MGEM, Aalfs CM, Gomez-Garcia EB, van’t Veer LJ, van Leeuwen FE, Rookus MA (2010) Physical activity and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 120(1):235–244

Klaren HM, van ‘t Veer LJ, van Leeuwen FE, Rookus MA (2003) Potential for bias in studies on efficacy of prophylactic surgery for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation. J Natl Cancer Inst 95(13):941–947

Heemskerk-Gerritsen BAM, Seynaeve C, van Asperen CJ, Ausems MGEM, Collee JM, van Doorn HC, Garcia EBG, Kets CM, van Leeuwen FE, Meijers-Heijboer HEJ, Mourits MJE, van Os TAM, Vasen HFA, Verhoef S, Rookus MA, Hooning MJ, Hebon (2015) Breast cancer risk after salpingo-oophorectomy in healthy BRCA1/2 mutation carriers: revisiting the evidence for risk reduction. J Natl Cancer Inst 107(5):33. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djv1033

Dutch breast cancer guidelines (2012). http://www.oncoline.nl

Simon R, Makuch RW (1984) A non-parametric graphical representation of the relationship between survival and the occurrence of an event—application to responder versus non-responder bias. Stat Med 3(1):35–44

Schultz LR, Peterson EL, Breslau N (2002) Graphing survival curve estimates for time-dependent covariates. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 11(2):68–74

Meijers-Heijboer H, van Geel B, van Putten WL, Henzen-Logmans SC, Seynaeve C, Menke-Pluijmers MB, Bartels CC, Verhoog LC, van den Ouweland AM, Niermeijer MF, Brekelmans CT, Klijn JG (2001) Breast cancer after prophylactic bilateral mastectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med 345(3):159–164

Skytte AB, Cruger D, Gerster M, Laenkholm AV, Lang C, Brondum-Nielsen K, Andersen MK, Sunde L, Kolvraa S, Gerdes AM (2011) Breast cancer after bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy. Clin Genet 79(5):431–437

Grann VR, Jacobson JS, Thomason D, Hershman D, Heitjan DF, Neugut AI (2002) Effect of prevention strategies on survival and quality-adjusted survival of women with BRCA1/2 mutations: an updated decision analysis. J Clin Oncol 20(10):2520–2529

Giannakeas V, Narod SA (2018) The expected benefit of preventive mastectomy on breast cancer incidence and mortality in BRCA mutation carriers, by age at mastectomy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 167(1):263–267

Ingham SL, Sperrin M, Baildam A, Ross GL, Clayton R, Lalloo F, Buchan I, Howell A, Evans DG (2013) Risk-reducing surgery increases survival in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers unaffected at time of family referral. Breast Cancer Res Treat 142(3):611–618

Metcalfe K, Eisen A, Senter L, Armel S, Bordeleau L, Meschino WS, Pal T, Lynch HT, Tung NM, Kwong A, Ainsworth P, Karlan B, Moller P, Eng C, Weitzel JN, Sun P, Lubinski J, Narod SA, the Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study G (2019) International trends in the uptake of cancer risk reduction strategies in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Br J Cancer 121(1):15–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-41019-40446-41411

Acknowledgements

We thank the Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Research Group Netherlands (HEBON) for providing the data. The HEBON consists of the following Collaborating Centers: Netherlands Cancer Institute (coordinating center), Amsterdam, NL: M.A. Rookus, F.B.L. Hogervorst, F.E. van Leeuwen, M.A. Adank, M.K. Schmidt, N.S. Russell, D.J. Jenner; Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, NL: J.M. Collée, A.M.W. van den Ouweland, M.J. Hooning, C. Seynaeve, C.H.M. van Deurzen, I.M. Obdeijn; Leiden University Medical Center, NL: C.J. van Asperen, J.T. Wijnen, R.A.E.M. Tollenaar, P. Devilee, T.C.T.E.F. van Cronenburg; Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, NL: C.M. Kets, A.R. Mensenkamp; University Medical Center Utrecht, NL: M.G.E.M. Ausems, R.B. van der Luijt; Amsterdam Medical Center, NL: C.M. Aalfs, H.E.J. Meijers-Heijboer, T.A.M. van Os; VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, NL: K. van Engelen, J.J.P. Gille, Q. Waisfisz; Maastricht University Medical Center, NL: E.B. Gómez-Garcia, M.J. Blok; University of Groningen, NL: J.C. Oosterwijk, A.H. van der Hout, M.J. Mourits, G.H. de Bock; The Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation (IKNL): S. Siesling, J.Verloop; The nationwide network and registry of histo- and cytopathology in The Netherlands (PALGA): L.I.H. Overbeek. The HEBON study is supported by the Dutch Cancer Society [Grant Nos. NKI1998-1854, NKI2004-3088, NKI2007-3756], the Netherlands Organisation of Scientific Research [Grant No. NWO 91109024], the Dutch Pink Ribbon foundation [Grant Nos. 110005 and 2014-187.WO76], BBMRI [Grant No. NWO 184.021.007/CP46] and Transcan [Grant No. JTC 2012 Cancer 12-054]. HEBON thanks the study participants and the registration teams of IKNL and PALGA for part of the data collection.

Funding

This work was supported by a Grant from the Dutch Pink Ribbon foundation (Grant No. 2016-209).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study, or from a close relative in case of already deceased individuals.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Heemskerk-Gerritsen, B.A.M., Jager, A., Koppert, L.B. et al. Survival after bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy in healthy BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 177, 723–733 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05345-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05345-2