Abstract

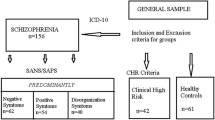

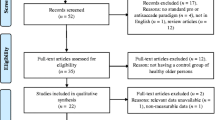

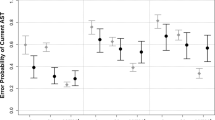

Saccadic eye movements are well-described markers of cerebral function and have been widely studied in schizophrenia spectrum populations. However, less is known about saccades in individuals clinically at risk for schizophrenia. Therefore, we studied individuals in an at-risk mental state (ARMS) (N = 160), patients in their first episode of schizophrenia (N = 32) and healthy controls (N = 75). N = 88 ARMS participants showed an early at-risk mental state (E-ARMS), defined by cognitive-perceptive basic symptoms (COPER) or a combination of risk and loss of function, whereas N = 72 were in a late at-risk mental state (L-ARMS), defined by attenuated psychotic symptoms or brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms. We examined prosaccades, reflecting overt attentional shifts, and antisaccades, measuring inhibitory control, as well as their relationship as an indicator of the interplay of bottom–up and top–down influences. L-ARMS but not E-ARMS participants had increased antisaccade latencies compared to controls. First-episode patients had higher antisaccade error rates compared to E-ARMS participants and controls, and increased latencies compared to all other groups. Prosaccade latencies did not differ between groups. We observed the expected negative correlation between prosaccade latency and antisaccade error rate, indicating that individuals with shorter prosaccade latencies made more antisaccade errors. The magnitude of the association did not differ between groups. No saccadic measure predicted conversion to psychosis within 2 years. These findings confirm the existence of antisaccade impairments in patients with schizophrenia and provide evidence that volitional response generation in the antisaccade task may be affected even before onset of clinically overt psychosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Nieman DH, McGorry PD (2015) Detection and treatment of at-risk mental state for developing a first psychosis: making up the balance. Lancet Psychiatry 2:825–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00221-7

Schultze-Lutter F, Michel C, Schmidt SJ et al (2015) EPA guidance on the early detection of clinical high risk states of psychoses. Eur Psychiatry 30:405–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.01.010

de Paula ALD, Hallak JEC, Maia-de-Oliveira JP et al (2015) Cognition in at-risk mental states for psychosis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 57:199–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.09.006

Bodatsch M, Brockhaus-Dumke A, Klosterkötter J, Ruhrmann S (2015) Forecasting psychosis by event-related potentials-systematic review and specific meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry 77:951–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.09.025

Wood SJ, Reniers RLEP, Heinze K (2013) Neuroimaging findings in the at-risk mental state: a review of recent literature. Can J Psychiatry 58:13–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371305800104

Hutton SB, Ettinger U (2006) The antisaccade task as a research tool in psychopathology: a critical review. Psychophysiology 43:302–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00403.x

Munoz DP, Everling S (2004) Look away: the anti-saccade task and the voluntary control of eye movement. Nat Rev Neurosci 5:218–228. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1345

Gooding DC, Basso MA (2008) The tell-tale tasks: a review of saccadic research in psychiatric patient populations. Brain Cogn 68:371–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2008.08.024

Calkins ME, Iacono WG, Ones DS (2008) Eye movement dysfunction in first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analytic evaluation of candidate endophenotypes. Brain Cogn 68:436–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2008.09.001

Ettinger U, Meyhöfer I, Steffens M et al (2014) Genetics, cognition, and neurobiology of schizotypal personality: A review of the overlap with schizophrenia. Frontiers Media SA

Gooding DC (1999) Antisaccade task performance in questionnaire-identified schizotypes. Schizophrenia Res 35:157–166

O’Driscoll GA, Lenzenweger MF, Holzman PS (1998) Antisaccades and smooth pursuit eye tracking and schizotypy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55:837–843

Nieman D, Becker H, van de Fliert R et al (2007) Antisaccade task performance in patients at ultra high risk for developing psychosis. Schizophr Res 95:54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2007.06.022

Caldani S, Bucci MP, Lamy J-C et al (2017) Saccadic eye movements as markers of schizophrenia spectrum: exploration in at-risk mental states. Schizophrenia Res 181:30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.09.003

Talanow T, Kasparbauer A-M, Steffens M et al (2016) Facing competition: neural mechanisms underlying parallel programming of antisaccades and prosaccades. Brain Cognit 107:37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2016.05.006

Reilly JL, Frankovich K, Hill S et al (2014) Elevated antisaccade error rate as an intermediate phenotype for psychosis across diagnostic categories. Schizophr Bull 40:1011–1021. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbt132

Fusar-Poli P, Cappucciati M, Borgwardt S et al (2016) Heterogeneity of psychosis risk within individuals at clinical high risk: a meta-analytical stratification. JAMA Psychiatry 73:113–120. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2324

Häfner H, Maurer K, Ruhrmann S et al (2004) Early detection and secondary prevention of psychosis: facts and visions. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 254:117–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-004-0508-z

Frommann I, Pukrop R, Brinkmeyer J et al (2011) Neuropsychological profiles in different at-risk states of psychosis: executive control impairment in the early—and additional memory dysfunction in the late—prodromal state. Schizophr Bull 37:861–873. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp155

Quednow BB, Frommann I, Berning J et al (2008) Impaired sensorimotor gating of the acoustic startle response in the prodrome of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiat 64:766–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.019

Frommann I, Brinkmeyer J, Ruhrmann S et al (2008) Auditory P300 in individuals clinically at risk for psychosis. Int J Psychophysiol 70:192–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.07.003

Wölwer W, Brinkmeyer J, Stroth S et al (2012) Neurophysiological correlates of impaired facial affect recognition in individuals at risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 38:1021–1029. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbr013

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (1997) Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-CV)

Maurer K, Hörrmann F, Trendler G et al (2006) Früherkennung des Psychoserisikos mit dem Early Recognition Inventory (ERIraos) Beschreibung des Verfahrens und erste Ergebnisse zur Reliabilität und Validität der Checkliste. Nervenheilkunde 25:11–16

American Psychiatric Association (2000) DSM-IV

Möller HJ, Riedel M, Jäger M et al (2008) Short-term treatment with risperidone or haloperidol in first-episode schizophrenia: 8-week results of a randomized controlled trial within the German research network on Schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 11(7):985–997. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1461145708008791

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA (1987) The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull 13:261–276

Montgomery SA, Asberg M (1979) A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to chnage. Br J Psychiatry 134:382–389

Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E (1993) Assessing depression in schizophrenia: the Calgary depression scale. Br J Psychiatry 163(S22):39–44

Lehrl S, Triebig G, Fischer B (1995) Multiple choice vocabulary test MWT as a valid and short test to estimate premorbid intelligence. Acta Neurol Scand 91:335–345

Maurer K, Häfner H (1995) Methodological aspects of onset assessment in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 15:265–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/0920-9964(94)00051-9

Stoline MR (1981) The status of multiple comparisons: simultaneous estimation of all pairwise comparisons in one-way ANOVA designs. Am Stat 35:134–141. https://doi.org/10.2307/2683979

Harris MSH, Reilly JL, Thase ME et al (2009) Response suppression deficits in treatment-naïve first-episode patients with schizophrenia, psychotic bipolar disorder and psychotic major depression. Psychiatry Res 170:150–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.10.031

Hutton SB, Crawford TJ, Puri BK et al (1998) Smooth pursuit and saccadic abnormalities in first-episode schizophrenia. Psychol Med 28:685–692

Ettinger U, Kumari V, Chitnis XA et al (2004) Volumetric neural correlates of antisaccade eye movements in first-episode psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 161:1918–1921. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.161.10.1918

Massen C (2004) Parallel programming of exogenous and endogenous components in the antisaccade task. The quarterly journal of experimental psychology A. Hum Exp Psychol 57:475–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724980343000341

Bechdolf A, Wagner M, Ruhrmann S et al (2012) Preventing progression to first-episode psychosis in early initial prodromal states. Br J Psychiatry 200:22–29. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.066357

Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR et al (2012) Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69(3):220–229. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1472

Fischer B, Weber H (1997) Effects of stimulus conditions on the performance of antisaccades in man. Exp Brain Res 116:191–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00005749

McDowell JE, Myles-Worsley M, Coon H et al (1999) Measuring liability for schizophrenia using optimized antisaccade stimulus parameters. Psychophysiology 36:138–141. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0048577299980836

Seidman LJ, Shapiro DI, Stone WS et al (2016) Association of neurocognition with transition to psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry 73:1239. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2479

Allott KA, Schäfer MR, Thompson A et al (2014) Emotion recognition as a predictor of transition to a psychotic disorder in ultra-high risk participants. Schizophr Res 153:25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2014.01.037

Calkins ME, Iacono WG, Curtis CE (2003) Smooth pursuit and antisaccade performance evidence trait stability in schizophrenia patients and their relatives. Int J Psychophysiol 49:139–146

Gooding DC, Shea HB, Matts CW (2005) Saccadic performance in questionnaire-identified schizotypes over time. Psychiatry Res 133:173–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2003.12.029

Gooding DC, Mohapatra L, Shea HB (2004) Temporal stability of saccadic task performance in schizophrenia and bipolar patients. Psychol Med 34:921–932

Ettinger U, Kumari V, Crawford TJ et al (2003) Reliability of smooth pursuit, fixation, and saccadic eye movements. Psychophysiology 40:620–628

Meyhöfer I, Bertsch K, Esser M, Ettinger U (2016) Variance in saccadic eye movements reflects stable traits. Psychophysiology 53:566–578. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12592

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) (Grant numbers BMBF 01GI 9934, 01GI 0234, 01GI9932, 01GI0232, 01GI0532). The funding source had no further role in the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; and the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MW, WW, WM, SR and JK conceived the study and obtained funding. MW designed the study and wrote the protocol. IF, WW, and ADB were responsible for data recording and management. LK and UE performed the analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors have contributed to data acquisition and to revising the manuscript and have approved the final manuscript. Luca Kleineidam (LK), Ingo Frommann (IF), Stephan Ruhrmann (SR), Joachim Klosterkötter (JK), Anke Brockhaus-Dumke (ABD) Wolfgang Wölwer (WW), Wolfgang Gaebel (WG), Wolfgang Maier (WM), Michael Wagner (MW), Ulrich Ettinger (UE).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kleineidam, L., Frommann, I., Ruhrmann, S. et al. Antisaccade and prosaccade eye movements in individuals clinically at risk for psychosis: comparison with first-episode schizophrenia and prediction of conversion. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 269, 921–930 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-018-0973-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-018-0973-4