Abstract

Summary

This study compared length of stay, hospital costs, 30-day readmission, and mortality for patients admitted primarily for osteoporotic fractures to those admitted for five other common health conditions. The results indicated that osteoporotic fractures were associated with highest hospital charges and the second highest hospital stay after adjusting for confounders.

Introduction

This study aimed to compare the effect of osteoporotic fractures and other common hospitalized conditions in both men and women age 55 years and older on a large in-patient sample.

Methods

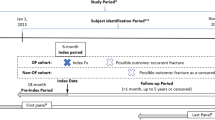

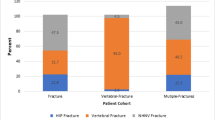

De-identified patient level and readmission and transfer data from the Virginia Health Information (VHI) system for 2008 through 2014 were merged. Logistic regression models were used to assess mortality and 30-day readmission, while generalized linear models were fitted to assess LOS and hospital charges.

Results

After adjustment for confounders, osteoporotic fractures had the second longest LOS (6.0 days, 95 % CI = 5.9–6.0) and the highest average total hospital charges ($47,386.0, 95 % CI = $46,707.0–$48,074.0) compared to the other five common health problems.

Conclusion

Recognizing risk and susceptibility to osteoporotic fractures is an important motivator for individual behaviors that mitigate this disease. Furthermore, acknowledging the economic impact and disabling burden of osteoporotic fractures on society are compelling reasons to promote bone health as well as to prevent, diagnose, and manage osteoporosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anderson G (2010) Chronic care: making the case for ongoing care. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2010/rwjf54583. Accessed 9 Dec 2015

Ortman J, Velkoff V, Hogan H (2014) An aging nation: the older population in the United States. http://www.census.gov/library/publications/2014/demo/p25-1140.html. Accessed 5 Jan 2016

Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, Curtis JR, Delzell ES, Randall S, Dawson-Hughes B (2014) The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res 29(11):2520–2526. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2269

Marks R, Allegrante JP, MacKenzie CR, Lane JM (2003) Hip fractures among the elderly: causes, consequences, and control. Ageing Res Rev 2:57–93. doi:10.1016/s1568-1637(02)00045-4

Nikkel LE, Fox EJ, Black KP, Davis C, Andersen L, Hollenbeak CS (2012) Impact of comorbidities on hospitalization costs following hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 94(1):9–17. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.01077

Singer A, Exuzides A, Spangler L, O’Malley C, Colby C, Johnston K, Agodoa I, Baker J, Kagan R (2015) Burden of illness for osteoporotic fractures compared with other serious diseases among postmenopausal women in the United States. Mayo Clin Proc 90(1):53–62. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.09.011

Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A (2006) Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res 22(3):465–475

National Osteoporosis Foundation (2014) 2014 annual report. http://nof.org/files/nof/public/content/report/6232/file/1298.pdf. Accessed 9 Dec 2015

Looker AC, Borrud LG, Dawson-Hughes B, Shepherd JA, Wright NC (2012) Osteoporosis or low bone mass at the femur neck or lumbar spine in older adults: United States, 2005–2008. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db93.htm. Accessed 12 Jan 2016

Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Milch VE, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA, Center JR (2009) Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. J Am Med Assoc 301(5):513–521. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.50

Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, Rosen AB (2009) Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. J Am Med Assoc 302(14):1573–1579. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1462

Shah AN, Vail TP, Taylor D, Pietrobon R (2004) Comorbid illness affects hospital costs related to hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 19(6):700–705. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2004.02.034

Lefaivre KA, Macadam SA, Davidson DJ, Gandhi R, Chan H, Broekhuyse HM (2009) Length of stay, mortality, morbidity, and delay to surgery in hip fractures. J Bone Joint Surg 91-B(7):922–927. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.91B7.22446

Kutsal YG, Atalay A, Arslan S, Basaran A, Canturk F, Cindas A, Eryavuz M, Irdesel J, Karadavut KI et al (2005) Awareness of osteoporotic patients. Osteoporos Int 16(2):128–133. doi:10.1007/s00198-004-1678-2

Virginia Health Information (2016) Patient level data. http://www.vhi.org/pld.asp. Accessed 9 Mar 2016

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) (2015) Clinical classifications software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. Available from https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed 5 Jan 2016

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) (2013) HCUP facts and figures. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/factsandfigures.jsp. Accessed 5 Jan 2016

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Alex KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

Office of the Surgeon General (US) (2004) Bone health and osteoporosis: a report of the surgeon general. Office of the Surgeon General (US), Rockville

Center JR, Nguyen TV, Schneider D, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA (1999) Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet 353(9156):878–882. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09075-8

Cummings SR, Melton LJ (2002) Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 359(9319):1761–1767. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08657-9

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Oglesby AK (2003) The components of excess mortality after hip fracture. Bone 32(5):468–473. doi:10.1016/S8756-3282(03)00061-9

Leboime A, Confavreux CB, Mehsen N, Paccou J, David C, Roux C (2010) Osteoporosis and mortality. Joint Bone Spine 77:S107–S112. doi:10.1016/S1297-319X(10)70004-X

Poor G, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ (1995) Determinants of reduced survival following hip fractures in men. Clin Orthop Relat Res 319:260–265. doi:10.1097/00003086-199510000-00028

Browner WS, Pressman AR, Nevitt MC, Cummings SR (1996) Mortality following fractures in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Arch Intern Med 156(14):1521–1525. doi:10.1001/archinte.1996.00440130053006

Cummings SR, Black DM, Rubin SM (1989) Lifetime risks of hip, Colles’, or vertebral fracture and coronary heart disease among white postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med 149(11):2445–2448. doi:10.1001/archinte.1989.00390110045010

Melton LJ (2000) Who has osteoporosis? A conflict between clinical and public health perspectives. J Bone Miner Res 15(12):2309–2314. doi:10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.12.2309

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIH (2014) Who is at risk for heart disease? http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/hdw/atrisk. Accessed 15 Dec 2015

Gerend MA, Aiken LS, West SG, Erchull MJ (2004) Beyond medical risk: investigating the psychological factors underlying women’s perceptions of susceptibility to breast cancer, heart disease, and osteoporosis. Health Psychol 23(3):247–258. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.247

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cunningham, T.D., Martin, B.C., DeShields, S.C. et al. The impact of osteoporotic fractures compared with other health conditions in older adults living in Virginia, United States. Osteoporos Int 27, 2979–2988 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3620-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3620-9