Abstract

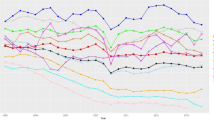

This paper empirically analyzes the existence of market power in the global iron ore market during the period from 1993 to 2012. Using an innovative stochastic frontier analysis approach, we investigate the relationship between individual firm characteristics, macroeconomic conditions and the individual ability of firms to generate markups in the global iron ore market. Our findings indicate that the markups on average amount to 20%. Moreover, location of the main production site and experience measured in years of production are identified to be the most important determinants of the magnitude of firm-specific markups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Following Schumpeter (1942), one may assess the finding of prices above marginal costs in light of dynamic competition as being the result of, e.g., goods of higher quality that, in the long run, may not lead to welfare losses but even to increasing consumer welfare.

Hereafter, when speaking of non-competitive behavior or the exercise of market power, we refer to a situation in which prices exceed marginal costs, i.e., we argue within a static competition framework.

Throughout this paper, when speaking of firms exercising market power no explicit assumption is made about the way the market power is exerted. Neither does the methodology applied here rely on any game theoretical model.

The monotonicity and concavity restrictions are tested ex post after the estimation.

For the case of companies operating in multiple countries, the country with the most production activity is chosen.

‘SEC Form 20-F’ is a necessary form to file with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) of the USA if the company is listed on the stock market in the USA.

For example, for Sesa Sterlite, only data on capital expenditure and total segment assets was available.

For the Ukraine, figures from UKRstat (2013) had to be used instead as data was not available from the OECD.

For 4 of the 10 companies, the fiscal year ends in June instead of December. Hence, without adjustment, different time periods would be compared. To adjust for these cases, two consecutive years are averaged, e.g., the average of the results for July 2004 to June 2005 and for July 2005 and June 2006 would form the value for the year 2005. A consequence of this adjustment is that the second half of 2004 and the first half of 2006 are included in the value for 2005. Furthermore, it reduces the number of observations from 100 to 96.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for raising this issue.

Note that only changes in the shadow cost may bias our markup estimates since we include firm fixed effects in our preferred specification, extracting the fixed part of markups. Another option to control for potential incentives from cooperation is to include time fixed effects as suggested by Puller (2009). Unfortunately, this is not feasible with the data at hand given the (highly) unbalanced nature of our panel data set and the resulting low number of observations in some years.

As the first-year observation of Atlas Iron may be an outlier, we re-estimated our model without this observation for a robustness check. The results confirm our previous findings.

In addition to our stochastic frontier model, we also estimate conventional OLS models. Using likelihood ratio (LR) tests, we evaluate whether a markup component exists at all. The LR tests have the null hypothesis: \(\lambda = 0\) with \(\lambda = \sigma _{u}/\sigma _{v}\) (Coelli et al. 2005). For all BC95 specifications, the null hypotheses that the OLS model is sufficient can be rejected at any conventional level of significance. Hence, the stochastic frontier model is preferred.

In case of BHP Billiton the estimated negative cost elasticities are in all likelihood due to the fact that we had to approximate the capital variable. Data on capital was only available on the total company level but not on the iron ore business segment level. Therefore, we used two alternative approximation approaches based on asset and revenue shares to proxy the capital variable. The estimation results for the two approaches do not differ significantly. Furthermore, all models were also estimated without the respective observations. The estimated coefficients are very similar to the coefficients presented in Table 4 and all cost elasticity estimates show positive values as required by economic theory. Therefore, in order to have more degrees of freedom, we opted to leave all observations in the frontier estimation and exclude the ones with negative cost elasticity estimates from the second-stage Lerner indices analysis. All estimation results are available from the authors upon request.

Given the differing magnitude between the two model specifications, the overall correlation of Lerner indices across specifications should be examined. The calculated Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.38 illustrates only a moderate correlation of Lerner indices across both specifications. This further stresses the importance of considering unobserved heterogeneity in the analysis.

LKAB is the only company (with large-scale operations) that is engaged in underground mining, which is associated with higher costs than production in open pit operations (Hellmer 1996).

Note that these figures are calculated in FE units in order to allow for comparison.

The main producer in the USA, Cliffs Natural Resources, however, does not seem to follow this hypothesis. Its average annual growth rate of production over the period 2000–2012 amounts to 10.3% and is therefore even larger than the rate for VALE. The time-varying Lerner indices, however, remain rather flat.

Hence, LKAB’s cost disadvantage may be outweighed by lower pelletizing costs due to a high magnetite fraction in the deposit (Hellmer 1996).

We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting the comparison of our estimated Lerner index values with individual profit-to-sales ratios. Full results on these figures are available from the authors upon request.

Note that this specification is not equivalent to individual fixed effects in the markup term, although each country is represented by one firm only. In contrast to individual fixed effects the reference group consists of a set of firms sharing the same characteristic (i.e., production in Australia) instead of one individual firm as in the fixed effects specification.

Time and firm indices are dropped for notational convenience.

As the marginal effects in the model without fixed effects (BC95) are negligible, we do not discuss them in the following. The results are available from the authors upon request.

This definition is used by Heij and Knapp (2014) and stems from the ship broker Braemar Seascope.

References

Amsler C, Prokhorov A, Schmidt P (2016) Endogeneity in stochastic frontier models. J Econom 190:280–288

Amsler C, Prokhorov A, Schmidt P (2017) Endogenous environmental variables in stochastic frontier models. J Econom 199(2):131–140

Angrist J, Pischke JS (2009) Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Asafu-Adjaye J, Mahadevan R (2003) How cost efficient are Australia’s mining industries? Energy Econ 25(4):315–329

Bain JS (1951) Relation of profit rate to industry concentration: American manufacturing, 1936–1940. Q J Econ 65(3):293–324

Bairagi S, Azzam A (2014) Does the Grameen Bank exert market power over borrowers. Appl Econ Lett 21(12):866–869

Battese GE, Coelli TJ (1995) A model for technical inefficiency effects in a stochastic production function for panel data. Empir Econ 20:325–332

Belotti F, Ilardi G (2012) Consistent estimation of the “True” Fixed Effects Stochastic Frontier Model. CEIS Research Papers 231

Bresnahan T (1989) Empirical studies of industries with market power. In: Schmalensee R, Willig R (eds) Handbook of industrial organization, vol II. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1011–1057

Christopoulou R, Vermeulen P (2012) Markups in the Euro area and the US over the period 1981–2004: a comparison of 50 sectors. Empir Econ 42:53–77

Coccorese P (2014) Estimating the Lerner index for the banking industry: a stochastic frontier approach. Appl Financ Econ 24(2):73–88

Coelli TJ, Henningsen A (2013) Package ‘frontier’. http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/frontier/frontier.pdf. Accessed 18 Sep 2013

Coelli TJ, Rao D, O’Donnell C, Battese G (2005) An introduction to efficiency and productivity analysis, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin

Demsetz H (1973) Industry structure, market rivalry, and public policy. J Law Econ 16:1–9

Elzinga K, Mills D (2011) The Lerner index of monopoly power: origins and uses. Am Econ Rev Pap Proc 101:558–564

European Commission (2004) Case COMP/M.2420 - Mitsui/CVRD/Caemi. Off J Eur Union L92:50–90

Färe R, Primont D (1995) Multi-output production and duality: theory and applications. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston

Farsi M, Filippini M, Greene WH (2005) Efficiency measurement in network industries: application to the Swiss railway companies. J Regul Econ 28(1):69–90

Filippini M, Wetzel H (2014) The impact of ownership unbundling on cost efficiency: empirical evidence from the New Zealand electricity distribution sector. Energy Econ 45:412–418

Galdon-Sanchez JE, Schmitz JJA (2002) Competitive pressure and labor productivity: world iron-ore markets in the 1980’s. Am Econ Rev 92(4):1222–1235

Greene WH (2005a) Fixed and random effects in stochastic frontier models. J Prod Anal 23(1):7–32

Greene WH (2005b) Reconsidering heterogeneity in panel data estimators of the stochastic frontier model. J Econom 126(2):269–303

Guan Z, Kumbhakar S, Myers R, Lansink AO (2009) Measuring excess capital capacity in agricultural production. Am J Agric Econ 91(3):765–776

Gunning TS, Sickles RC (2013) Competition and market power in physician private practices. Empir Econ 44:1005–1029

Hall RE (1988) The relation between price and marginal cost in U.S. industry. J Polit Econ 96(5):921–947

Heij C, Knapp S (2014) Dynamics in the dry bulk market: economic activity, trade flows, and safety in shipping. J Transp Econ Policy 48(3):499–514

Hellmer S (1996) The role of product differentiation in the iron ore industry: the case of LKAB. Resour Policy 22(1/2):49–60

Hellmer S, Ekstrand J (2013) The iron ore world market in the early twenty-first century: the impact of the increasing Chinese dominance. Miner Econ 25(2–3):89–95

Hilpert HG, Wassenberg F (2010) Monopoly auf dem Eisenerzmarkt: Ursachen und Konsequenzen. Wirtschaftsdienst 90(8):564–566

Hobbs BF (1986) Mill pricing versus spatial price discrimination under Bertrand and Cournot spatial competition. J Ind Econ 35(2):173–191

Hotelling H (1931) The economics of exhaustible resources. J Polit Econ 39(2):137–175

Huang TH, Liu NH (2014) Bank competition in transition countries: are those markets really in equilibrium. Empir Econ 47:1283–1316

Hurst L (2012) West and Central African iron ore: a lesson in the contestability of the iron ore market. EABER Working Paper Series

IMF (2014) World Economic Outlook database. International Monetary Fund. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2014/01/weodata/index.aspx. Accessed 25 Aug 2014

Jondrow J, Lovell CK, Materov IS, Schmidt P (1982) On the estimation of technical inefficiency in the stochastic frontier production function model. J Econom 19(2–3):233–238

Karakaplan MU, Kutlu L (2017a) Endogeneity in panel stochastic frontier models: an application to the Japanese cotton spinning industry. Appl Econ 49(59):5935–5939

Karakaplan MU, Kutlu L (2017b) Handling endogeneity in stochastic frontier analysis. Econ Bull 37(2):889–901

Kumbhakar S, Baardsen S, Lien G (2012) A new method for estimating market power with an application to Norwegian sawmilling. Rev Ind Org 40(2):109–129

Kumbhakar SC, Sun K (2013) Derivation of marginal effects of determinants of technical inefficiency. Econ Lett 120(2):249–253

Kutlu L (2010) Battese–Coelli estimator with endogenous regressors. Econ Lett 109:79–81

Kutlu L, Sickles RC (2012) Estimation of market power in the presence of firm level inefficiencies. J Econom 168(1):141–155

Kutlu L, Tran K, Tsionas EG (2017) A time-varying true individual effects model with endogenous regressors. Working Paper

Lerner AP (1934) The concept of monopoly and the measurement of monopoly power. Rev Econ Stud 1(3):157–175

Levhari D, Liviatan N (1977) Notes on Hotelling’s economics of exhaustible resources. Can J Econ 10(2):177–192

Lovell CAK, Richardson S, Travers P, Wood LL (1994) Resources and functionings: a new view of inequality in Australia. In: Eichhorn W (ed) Models and measurement of welfare and inequality. Springer, Berlin, pp 787–807

Lundmark R, Warell L (2008) Horizontal mergers in the iron ore industry: an application of PCAIDS. Resour Policy 33(3):129–141

OECD (2013) Consumer prices (mei). Main Economic Indicators (MEI), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=MEI_PRICES. Accessed 2 July 2013

Orea L, Steinbuks J (2018) Estimating market power in homogenous product markets using a composed error model: application to the California electricity market. Econ Inq 56(2):1296–1321

Peltzman S (1977) The gains and losses from industrial concentration. J Law Econ 20(2):229–263

Pindyck RS (1978) The optimal exploration and production of nonrenewable resources. J Polit Econ 86(5):841–861

Pindyck RS (1985) The measurement of monopoly power in dynamic markets. J Law Econ 28(1):193–222

Puller SL (2009) Estimation of competitive conduct when firms are efficiently colluding: addressing the Corts critique. Appl Econ Lett 16(15):1497–1500

Rezitis AN, Kalantzi MA (2016) Evaluating the state of competition and the welfare losses in the Greek manufacturing sector: an extended Hall–Roeger approach. Empir Econ 50(4):1275–1302

Roeger W (1995) Can imperfect competition explain the difference between primal and dual productivity measures? Estimates for U.S. manufacturing. J Polit Econ 103(2):316–330

Roskill (2000) The economics of iron ore, 4th edn. Roskill Information Services, London

Schumpeter JA (1942) Capitalism, socialism, democracy. Harper, New York

Shephard RW (1970) Theory of cost and production functions. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Stango V (2000) Competition and pricing in the credit card market. Rev Econ Stat 82(3):499–508

Sukagawa P (2010) Is iron ore priced as a commodity? Past and current practice. Resour Policy 35(1):54–63

Tilton JE (2001) Labor productivity, costs, and mine survival during a recession. Resour Policy 27(2):107–117

Tran K, Tsionas EG (2013) GMM estimation of stochastic frontier model with endogenous regressors. Econ Lett 118(1):233–236

UKRstat (2013) Consumer price indices for goods and services in 2002–2012. http://ukrstat.org/en/operativ/operativ2008/ct/cn_rik/icsR/iscR_e/isc_tp_rik_e.htm. Accessed 02 July 2013

UNCTAD (2011) Global iron ore, positive long-term outlook. In: Global Commodities Forum

Wang HJ (2002) Heteroscedasticity and non-monotonic efficiency effects of a stochastic frontier model. J Prod Anal 18(3):241–253

Warell L (2014) The effect of a change in pricing regime on iron ore prices. Resour Policy 41:16–22

Wilson JD (2012) Chinese resource security policies and the restructuring of the Asia-Pacific iron ore market. Resour Policy 37(3):331–339

Worldbank (2013) PPP conversion factor, GDP (LCU per international \$). World Bank, International Comparison Program database. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.PPP. Accessed 2 July 2013

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers, Felix Höffler and Frank Pothen as well as participants at the 2015 AURÖ Workshop in Hamburg and at the EARIE 2015 in Munich for their helpful comments and suggestions. An earlier version of this paper circulated under the title ‘Investigating the Influence of Firm Characteristics on the Ability to Exercise Market Power - A Stochastic Frontier Analysis Approach with an Application to the Iron Ore Market’.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Germeshausen, R., Panke, T. & Wetzel, H. Firm characteristics and the ability to exercise market power: empirical evidence from the iron ore market. Empir Econ 58, 2223–2247 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1610-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1610-9