Abstract

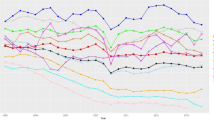

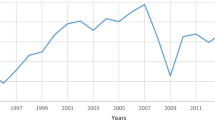

Despite the extensive literature on product market power, evidence on markups at the firm level and which also accounts for labour market power is still limited. In this paper, we investigate the trends in both these market frictions in a large sample of Italian manufacturing firms over the period 2010–2018. In doing so, we devote particular attention to the factors underlying product market power, and especially to the way the markup is related to labour market power and the labour share of income. Our analysis reveals that, during the selected years, the manufacturing sector has experienced a limited rise in markups and a shift in labour market power away from firms and towards workers. These dynamics are mostly driven by within-firm changes. Additionally, the overall growth in bargaining power, which explains the muted positive trend in the labour share, is mainly ascribable to the rise in the average firm-level wages. However, the latter are likely to hide relevant inter-individual heterogeneity, as national data on wage inequality suggest, and monopsony power is still a widespread phenomenon, especially in the Mezzogiorno.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In particular, in the last two decades it has experienced a gradual but steady growth in labour force participation, a trend in the labour share which, despite a contraction in the early 2000s, is less worrying than the US one, and an investment rate that has been recovering after the fall occurred in 2010. At the same time, it has exhibited a low business turnover rate (e.g., Cefis & Gabriele, 2009; Rungi & Biancalani, 2019), increasing income inequality (e.g., Ciani & Torrini, 2019; Devicienti et al., 2019) and growing capital misallocation (e.g., Gamberoni et al., 2016), which have been regarded as possible symptoms of increasing product market power (see Mondolo (2021) for an overview of these trends in Italy and for a comparison with the US and the EU as a whole).

We estimate the production function for each of the eleven manufacturing sectors listed in Table 3. To define such sectors, we follow the classification by “divisione ateco” used by Istat. We condense the observations corresponding to ate2/divisione ateco 20 and 21 in one sector (Chemicals and Pharmaceutical products) due to the limited number of observations. Moreover, we exclude divisione ateco 19 (Coke and refined petroleum products) due to its limited extension in the Italian manufacturing and to its peculiarities.

It can be observed that the entry component experienced a “jump” between 2010 and 2011. Several firms indeed entered the Aida dataset that year, irrespective of the year of foundation. We also tried to keep in the final sample only the firms for which data are available for the whole period; the main results in terms of trends of market frictions and their components do not significantly change.

Since the late 1990s, the Italian labour market has undertaken a gradual process of reform which is supposed to increase labour market flexibility The Law 183 of 2014, mostly known as Jobs Act, is the last step of a reform process which started with the introduction of a set of temporary and para-subordinated contracts (the ‘‘Legge Treu’’ of 1997) and continued with the Law n.30/2003 (“Legge Biagi”), which provided a common framework to atypical contracts, and law n. 92 by Minister Fornero. The so-called Riforma Fornero weakened the regime that protects regular workers against the risk of unfair dismissal, and at the same time attempted to improve the coverage of unemployment insurance benefits, in particular by replacing a rather broken web of individual schemes with a more unified system of unemployment protection (see for instance Cirillo et al., 2017; Moreira et al., 2015, for a review). In the meantime, the OECD indicator of Strictness of employment protection referring to individual and collective dismissals, which remained constant from the first year available (1990) until 2013, declined by about 18% between 2013 and 2018. A decline in this indicator during the same period has been observed also in other European countries, such as Spain, Portugal and the UK.

For a review of the literature that study the link between product market power/markups and the labour share, see Mondolo (2021)

In Mertens (2019), the indicator of labour market power \(\varphi \) is calculated as \({MRP}_{it}^{L}/{w}_{it},\) hence an increase in Mertens’ \(\varphi \) corresponds to a shift of labour market power from the employees to the employers, namely to a rise in monopsony power. In Eq. (5), which can be recovered by simply rearranging the terms of Eq. (3), \(\varphi \) is computed as \({w}_{it}/{MRP}_{it}^{L}\), consistent with our definition of labour market power introduced in Eq. (2) and applied in the rest of this work.

The value-added labour share, calculated as the ratio between compensation of employees and value added, exhibits a more ambiguous trend. We focus on the revenue-based labour share because it is the one that is linked to product (and labour) market power by the specific relationship captured by Eqs. (5) and (6).

References

Ackerberg, D. A., Caves, K., & Frazer, G. (2015). Identification properties of recent production function estimators. Econometrica, 83(6), 2411–2451.

Andrews, D., & Cingano, F. (2014). Public policy and resource allocation: Evidence from firms in Oecd countries. Economic Policy, 29(78), 253–296.

Barkai, S. (2020). Declining labour and capital shares. The Journal of Finance, 75(5), 2421–2463.

Basu, S. (2019). Are price-cost markups rising in the United States? A discussion of the evidence. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(3), 3–22.

Battiati, C., Jona-Lasinio, C., Marvasi, E., & Sopranzetti, S. (2022). Markups, productivity and Global Value Chains in the European economies. Economia Italiana, 1, 73–108.

Bellone, F., Musso, P., Nesta, L., & Warzynski, F. (2016). International trade and firm-level markups when location and quality matter. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(1), 67–91.

Blanchard, O., & Giavazzi, F. (2003). Macroeconomic effects of regulation and deregulation in goods and labour markets. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(3), 879–907.

Bugamelli, M., Fabiani, S., & Sette, E. (2015). The age of the dragon: Chinese competition and the pricing behavior of Italian firms. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 47(6), 1091–1118.

Bugamelli, M., Schivardi, F., & Zizza, R. (2008). The Euro and Firm Restructuring. NBER Working Paper No. 14454.

Calligaris, S., Criscuolo, C., & Marcolin, L. (2018). Mark-ups in the digital era. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Paper 2018/10.

Caselli, M., Mondolo, J., & Schiavo, S. (2020). The evolution of labour market power in Italy and the impact of a minimum wage. Presented at the international workshop "Firms and Workers at the Crossroad: Automation & Market Power". University of Trento, Trento (Italy), December 21, 2020.

Caselli, M., Nesta, L., & Schiavo, S. (2021). Imports and labour market imperfections: Firm-level evidence from France. European Economic Review, 131, 103632.

Cavalleri, M. C., Eliet, A., Mcadam, P., Petroulakis, F., Soares, A., & Vansteenkiste, I. (2019). Concentration, market power and dynamism in the euro area. ECB Working Paper Series No. 2253, ECB-European Central Bank.

Cefis, E., & Gabriele, R. (2009). Spatial disaggregation patterns and structural determinants of job flows: An empirical analysis. International Review of Applied Economics, 23(1), 89–111.

Ciani, E., & Torrini, R. (2019). The geography of Italian income inequality: recent trends and the role of employment. Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers) No. 492, Bank of Italy.

Ciapanna, E., Formai, S., Linarello, A., & Rovigatti, G. (2022). Measuring market power: macro and micro evidence from Italy. Questioni Di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers) No. 672, Bank of Italy.

Cirillo, V., Fana, M., & Guarascio, D. (2017). Labour market reforms in Italy: Evaluating the effects of the Jobs Act. Economia Politica, 34, 211–232.

Crafts, N., & Mills, T. (2005). TFP growth in British and German manufacturing, 1950–1996. The Economic Journal, 115, 649–670.

De Loecker, J., & Eeckhout, J. (2018). Global Market Power. NBER Working Paper No. 24768.

De Loecker, J., Eeckhout, J., & Unger, G. (2020). The rise of market power and the macroeconomic implications. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(2), 561–644.

De Loecker, J., & Warzynski, F. (2012). Markups and firm-level export status. American Economic Review, 102(6), 2437–2471.

Devicienti, B., Fanfani, A., & Maida, A. (2019). Collective bargaining and the evolution of wage inequality in Italy. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 57(2), 377–407.

Diez, F., Fan, J., & Villegas-Sánchez, C. (2019). Global Declining Competition. IMF Working Paper No. 19/82.

Díez, F., Leigh, D., & Tambunlertchai, S. (2018). Global Market Power and its Macroeconomic Implications. IMF Working Paper No. 18/137.

Dixon, R., & Lim, G. (2020). Is the decline in labour’s share in the US driven by changes in technology and/or market power? An empirical analysis. Applied Economics, 52(59), 6400–6415.

Dobbelaere, S., & Kiyota, K. (2018). Labour market imperfections, markups and productivity in multinationals and exporters. Labour Economics, 53, 198–212.

Dobbelaere, S., & Mairesse, J. (2013). Panel data estimates of the production function and product and labour market imperfections. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 28(1), 1–46.

Domowitz, I., Hubbard, G., & Petersen, B. (1988). Market structure and cyclical fluctuations. Review of Economics and Statistics, 70(1), 55–66.

Eggertsson, G. B., Robbins, J. A., & Wold, E. G. (2021). Kaldor and Piketty’s facts: The rise of monopoly power in the United States. Journal of Monetary Economics, 124(Supplement), S19–S38.

Feeny, S., Harris, M., & Rogers, M. (2005). A dynamic panel analysis of the profitability of Australian tax entities. Empirical Economics, 30, 209–233.

Forni, L., Gerali, A., & Pisani, M. (2014). Macroeconomic effects of greater competition in the service sector: the case of Italy. Banca d’Italia Temi di Discussione (Working Papers), No. 706.

Foster, L., Haltiwanger, J.C., & Krizan, C.J. (2001). Aggregate Productivity Growth: Lessons from Microeconomic Evidence (pp. 303–372). University of Chicago Press. http://www.nber.org/books/hult01-1

Gamberoni, E., Giordano, C., & Lopez-Garcia, P. (2016). Capital and labour (mis)allocation in the euro area: some stylized facts and determinants. Bank of Italy “Questioni di Economia e Finanza” (Occasional Papers) No. 349, Bank of Italy.

Giordano, C., & Zollino, F. (2017). Macroeconomic estimates of Italy’s mark-ups in the long-run, 1861–2012. Bank of Italy Economic History Working Paper No. 39, Bank of Italy.

Hall, R. E. (1986). Market structure and macroeconomic fluctuations. Brookings Papers on Economic Activities, 2(1986), 285–322.

IMF. (2019). World Economic Outlook, April 2019. Growth Slowdown, Precarious Recovery. Washington, DC.

Kato, A. (2014). Does Export Yield Productivity and Markup Premiums? Evidence from the Japanese manufacturing industry, RIETI Discussion Paper 14-E-037, Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

Klette, T. (1999). Market power, scale economies and productivity: Estimates from a panel of establishment data. Journal of Industrial Economics, 47(4), 451–476.

Levinsohn, J., & Petrin, A. (2003). Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. The Review of Economic Studies, 70(2), 317–341.

Mertens, M. (2019). Micro-mechanisms behind declining labour shares: Market power, production processes, and global. IWH-CompNet Discussion Paper No. 3/2019, Leibniz-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung Halle (IWH).

Mertens, M. (2020). Labour market power and the distorting effects of international trade. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 68, 102562.

Mondolo, J. (2021). Macroeconomic dynamics and the role of market power. The case of Italy. DEM Working Papers No. 2021/17, DEM-Department of Economics and Management, University of Trento.

Moreira, A., Alonso-Domínguez, À., Antunes, C., Karamessini, M., Raitano, M., & Glatzer, M. (2015). Austerity-driven labour market reforms in Southern Europe: Eroding the security of labour market insiders. European Journal of Social Security, 17(2), 202–225.

Morrison, C. (1988). Unraveling the productivity growth slowdown in the United States, Canada and Japan: The effects of subequilibrium, scale economies and markups. Review of Economics and Statistics, 74(3), 381–393.

Olley, S., & Pakes, A. (1996). The dynamics of productivity in the telecommunications equipment industry. Econometrica, 64, 1263–1297.

Petrin, A., & Levinsohn, J. (2012). Measuring aggregate productivity growth using plant-level data. RAND Journal of Economics, 43(4), 705–725.

Ponikvar, N., & Tajnikar, M. (2011). Are the determinants of markup size industry-specific? The case of slovenian manufacturing firms. Panoeconomicus, 58(2), 229–244.

Restuccia, D., & Rogerson, R. (2013). Misallocation and productivity: Editorial. Review of Economic Dynamics, 16(1), 1–10.

Restuccia, D., & Rogerson, R. (2017). The causes and costs of misallocation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(3), 151–174.

Roeger, W. (1995). Can imperfect competition explain the difference between primal and dual productivity measures? Estimates for U.S. manufacturing. Journal of Political Economy, 103(2), 316–330.

Rungi, A., & Biancalani, F. (2019). Heterogeneous firms and the North-South divide in Italy. Italian Economic Journal, 5(3), 325–347.

Soares, A. (2020). Price cost margin and bargaining power in the European Union. Empirical Economics, 59(5), 2093–2123.

Syverson, C. (2019). Macroeconomics and market power. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(3), 23–43.

van Heuvelen, G., Bettendorf, L., & Meijerink, G. (2019). Estimating Markups in the Netherlands. CPB Background Document, CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis.

Wooldridge, J. (2009). On estimating firm-level production functions using proxy variables to control for unobservables. Economic Letters, 104(3), 112–114.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Stefano Schiavo and Mauro Caselli for their very useful suggestions.

Funding

Fondazione Cassa Di Risparmio Di Trento E Rovereto.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Estimation of the production function

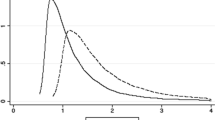

In Sect. 2, following De Loecker and Warzynski (2012), we defined the firm-level markup as the ratio between of the output elasticity of materials and its revenue share:

where \({\mu }_{it}\) is the markup of firm \(i\) at time \(t\), \({\theta }_{it}^{M}\) is the output elasticity of materials and \({\alpha }_{it}^{M}\) is the revenue share of materials, also known as cost share or expenditure share of materials. While the expenditure share of materials can be easily computed using firm-level data that are generally available, the related output elasticity needs to be estimated.

In order to get unbiased estimates of \({\theta }_{it}^{M}\) at the firm-year level, we consider the following general production function Q for firm i at time t:

where \({L}_{it}\), \({M}_{it}\) and \({K}_{it}\) are the firms’ inputs (i.e., labour, materials and capital, respectively) and \({w}_{it}\) is firm’s productivity. Unobserved productivity shocks are potentially correlated with input choices, and if not controlled for, can lead to inconsistent estimates of the production function. Accordingly, we employ the Wooldridge-Levinsohn-Petrin (WLP) estimator, as derived from Wooldridge (2009) and implemented in Petrin and Levinsohn (2012). The WLP estimator does not assume constant returns to scale, is robust to the Ackerberg et al. (2015) criticism of Levinsohn and Petrin’s (2003) estimator and is programmed as a simple instrumental variable estimator. The potential endogeneity issues related to the simultaneous determination of inputs and unobserved productivity are addressed by introducing lagged values of specific inputs as proxies for productivity.

Specifically, the estimation strategy used in this paper consists in two steps.

First, we run:

where we use a third-order polynomial on all inputs to remove the random-error term \({\in }_{it}\) from the output and hence to obtain estimates of the expected output \(\widehat{{q}_{it}}\). Then, we use a general production function of the following type:

where \(\widehat{{q}_{it}}\) is the natural log of real sales of firm \(i\) at time \(t\), \({l}_{it}\), \({k}_{it}\) and \({m}_{it}\) are, respectively, the natural logarithms of the quantities of labour, capital and materials used by the firm and that get transformed into the output according to the production function \({f}_{s}\), \(\mathrm{B}\) is the parameter vector to be estimated in order to calculate the output elasticities, \({\omega }_{it}\) is the firm-level productivity term that is observable by the firm but not by the econometrician, and \({\varepsilon }_{it}\) is an error term that is unobservable to both the firm and the econometrician. Productivity is, thus, assumed to be Hicks neutral and specific to the firm, as in the approach using inputs to control for unobservables in production function estimations (Ackerberg et al., 2015; Levinsohn & Petrin, 2003; Olley & Pakes, 1996). We assume that labour is a variable input, and instrument current labour and materials and their interactions with the first and second lags of labour as well as the second lags of capital and materials. To control for time-variant shocks common to all plants, we add year fixed effects.

We adopt a translog specification, which, unlike the Cobb–Douglas, permits us to recover firm-level time-variant output elasticities. The production function is a revenue function, since data on firms’ output prices are not available, and is allowed to change across different sectors, as implied by the subscript s. Leaving subscripts \(i\) and \(t\) aside for simplicity, the translog function \({f}_{s}\) can be written as:

Thus, the parameter vector is made up of nine parameters for each sector.

The estimated parameters of the translog production function allow us to compute the output elasticity of materials. Using the estimates of the output elasticity and the calculated revenue shares of materials, we can now compute markups at the firm-year level based on Eq. (1).

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mondolo, J. Product and labour market imperfections in the Italian manufacturing sector: a firm-level analysis. Econ Polit 39, 813–838 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-022-00280-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-022-00280-w