Abstract

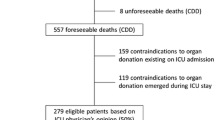

The success of any donation process requires that potential brain-dead donors (PBDD) are detected and referred early to professionals responsible for their evaluation and conversion to actual donors. The intensivist plays a crucial role in organ donation. However, identification and referral of PBDDs may be suboptimal in the critical care environment. Factors influencing lower rates of detection and referral include the lack of specific training and the need to provide concomitant urgent care to other critically ill patients. Excellent communication between the ICU staff and the procurement organization is necessary to ensure the optimization of both the number and quality of organs transplanted. The organ donation process has been improved over the last two decades with the involvement and commitment of many healthcare professionals. Clinical protocols have been developed and implemented to better organize the multidisciplinary approach to organ donation. In this manuscript, we aim to highlight the main steps of organ donation, taking into account the following: early identification and evaluation of the PBDD with the use of checklists; donor management, including clinical maintenance of the PBDD with high-quality intensive care to prevent graft failure in recipients and strategies for optimizing donated organs by simplified care standards, clinical guidelines and alert tools; the key role of the intensivist in the donation process with the interaction between ICU professionals and transplant coordinators, nurse protocol managers, and communication skills training; and a final remark on the importance of the development of research with further insight into brain death pathophysiology and reversible organ damage.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Niemann CU, Matthay MA, Ware LB (2018) The continued need for clinical trials in deceased organ donor management. Transplantation. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000002512

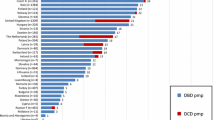

Matesanz R, Domínguez-Gil B, Coll E et al (2017) How Spain reached 40 deceased organ donors per million population. Am J Transpl 17:1447–1454. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.14104

Saidi RF, Hejazii Kenari SK (2014) Challenges of organ shortage for transplantation: solutions and opportunities. Int J organ Transpl Med 5:87–96

Westphal GA, Slaviero TA, Montemezzo A et al (2016) The effect of brain death protocol duration on potential donor losses due to cardiac arrest. Clin Transpl 30:1411–1416. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.12830

Hoste P, Ferdinande P, Vogelaers D et al (2018) Adherence to guidelines for the management of donors after brain death. J Crit Care 49:56–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.10.016

Westphal GA, Coll E, de Souza RL et al (2016) Positive impact of a clinical goal-directed protocol on reducing cardiac arrests during potential brain-dead donor maintenance. Crit Care 20:323. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1484-1

Jawoniyi O, Gormley K, McGleenan E, Noble HR (2018) Organ donation and transplantation: awareness and roles of healthcare professionals—a systematic literature review. J Clin Nurs 27:e726–e738. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14154

Marchand AJ, Seguin P, Malledant Y et al (2016) Revised CT angiography venous score with consideration of infratentorial circulation value for diagnosing brain death. Ann Intensive Care 6:88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-016-0188-7

Casartelli M, Bombardini T, Simion D et al (2012) Wait, treat and see: echocardiographic monitoring of brain-dead potential donors with stunned heart. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 10:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-7120-10-25

Malinoski DJ, Patel MS, Daly MC et al (2012) The impact of meeting donor management goals on the number of organs transplanted per donor: results from the United Network for Organ Sharing Region 5 prospective donor management goals study. Crit Care Med 40:2773–2780. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825b252a

Patel MS, Zatarain J, De La Cruz S et al (2014) The impact of meeting donor management goals on the number of organs transplanted per expanded criteria donor: a prospective study from the UNOS region 5 donor management goals workgroup. JAMA Surg 149:969–975. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2014.967

Patel MS, De La Cruz S, Sally MB et al (2017) Active donor management during the hospital phase of care is associated with more organs transplanted per donor. J Am Coll Surg 225:525–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.06.014

Weil MH, Shubin H (1969) The “VIP” approach to the bedside management of shock. JAMA 207:337–340

Westphal GA (2016) A simple bedside approach to therapeutic goals achievement during the management of deceased organ donors—an adapted version of the “VIP” approach. Clin Transpl 30:138–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.12667

Matesanz R, Domínguez-Gil B, Marazuela R et al (2012) Benchmarking in organ donation after brain death in Spain. Lancet 380:649–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61371-3

Hunter JP, Ploeg RJ (2016) An exciting new era in donor organ preservation and transplantation: assess, condition, and repair! Transplantation 100:1801–1802. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000001300

Boffa C, Curnow E, Martin K et al (2017) The impact of duration of brain death on outcomes in abdominal organ transplantation. Transplantation 101:S1. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.tp.0000524966.72734.fb

Tullius SG, Rabb H (2018) Improving the supply and quality of deceased-donor organs for transplantation. N Engl J Med 378:1920–1929. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1507080

Inaba K, Branco BC, Lam L et al (2010) Organ donation and time to procurement: late is not too late. J Trauma 68:1362–1366. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3181db30d3

Madan S, Saeed O, Vlismas P et al (2017) Outcomes after transplantation of donor hearts with improving left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 70:1248–1258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.07.728

Wauters S, Verleden GM, Belmans A et al (2011) Donor cause of brain death and related time intervals: does it affect outcome after lung transplantation? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 39:e68–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.11.049

Giwa S, Lewis JK, Alvarez L et al (2017) The promise of organ and tissue preservation to transform medicine. Nat Biotechnol 35:530–542. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3889

Niemann CU, Feiner J, Swain S et al (2015) Therapeutic hypothermia in deceased organ donors and kidney-graft function. N Engl J Med 373:405–414. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1501969

Feng S (2017) Optimizing graft survival by pretreatment of the donor. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12:388–390. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.00900117

Domínguez-Gil B, Murphy P, Procaccio F (2016) Ten changes that could improve organ donation in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med 42:264–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-3833-y

Manara AR, Thomas I, Harding R (2016) A case for stopping the early withdrawal of life sustaining therapies in patients with devastating brain injuries. J Intensive Care Soc 17:295–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/1751143716647980

Hoste P, Hoste E, Ferdinande P et al (2018) Development of key interventions and quality indicators for the management of an adult potential donor after brain death: a RAND modified Delphi approach. BMC Health Serv Res 18:580. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3386-1

de la Rosa G, Domínguez-Gil B, Matesanz R et al (2012) Continuously evaluating performance in deceased donation: the Spanish quality assurance program. Am J Transpl 12:2507–2513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04138.x

Kramer AH, Zygun DA, Doig CJ, Zuege DJ (2013) Incidence of neurologic death among patients with brain injury: a cohort study in a Canadian health region. CMAJ 185:E838–E845. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.130271

Simpkin AL, Robertson LC, Barber VS, Young JD (2009) Modifiable factors influencing relatives’ decision to offer organ donation: systematic review. BMJ 338:b991. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b991

Vincent A, Logan L (2012) Consent for organ donation. BJA Br J Anaesth 108:i80–i87. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aer353

Murugan R, Venkataraman R, Wahed AS et al (2009) Preload responsiveness is associated with increased interleukin-6 and lower organ yield from brain-dead donors. Crit Care Med 37:2387–2393. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a960d6

World Health Organization (2017) Clinical criteria for the determination of death, WHO technical expert consultation, WHO Headquarters, 22–23 September 2014. World Health Organization, Geneva. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/254737

Drake M, Bernard A, Hessel E (2017) Brain death. Surg Clin North Am 97:1255–1273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2017.07.001

Ventetuolo CE, Muratore CS (2014) Extracorporeal life support in critically ill adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 190:497–508. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201404-0736CI

Meyer K, Bjørk IT (2008) Change of focus: from intensive care towards organ donation. Transpl Int 21:133–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00583.x

(2011) The Madrid resolution on organ donation and transplantation: national responsibility in meeting the needs of patients, guided by the WHO principles. Transplantation 91(Suppl 1):S29–S31. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.tp.0000399131.74618.a5

Ozdemir BA, Karthikesalingam A, Sinha S et al (2015) Research activity and the association with mortality. PLoS One 10:e0118253. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118253

Salim A, Velmahos GC, Brown C et al (2005) Aggressive organ donor management significantly increases the number of organs available for transplantation. J Trauma 58:991–994

Michard F, Boussat S, Chemla D et al (2000) Relation between respiratory changes in arterial pulse pressure and fluid responsiveness in septic patients with acute circulatory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162:134–138. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.162.1.9903035

Murugan R, Venkataraman R, Wahed AS et al (2008) Increased plasma interleukin-6 in donors is associated with lower recipient hospital-free survival after cadaveric organ transplantation. Crit Care Med 36:1810–1816. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e318174d89f

Majchrzak-Gorecka M, Majewski P, Grygier B et al (2016) Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI), a multifunctional protein in the host defense response. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 28:79–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2015.12.001

Li S, Wang S, Murugan R et al (2018) Donor biomarkers as predictors of organ use and recipient survival after neurologically deceased donor organ transplantation. J Crit Care 48:42–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.08.013

Domínguez-Gil B, Delmonico FL, Shaheen FAM et al (2011) The critical pathway for deceased donation: reportable uniformity in the approach to deceased donation. Transpl Int 24:373–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01243.x

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

No COIs to declare by any of the authors of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

An ethical approval was not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martin-Loeches, I., Sandiumenge, A., Charpentier, J. et al. Management of donation after brain death (DBD) in the ICU: the potential donor is identified, what's next?. Intensive Care Med 45, 322–330 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05574-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05574-5