Abstract

Background

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is the main cause of global and in-hospital mortality in patients with cardiovascular diseases. We aimed to examine the association between the coronary artery involved and the in-hospital mortality in patients who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) after ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Methods

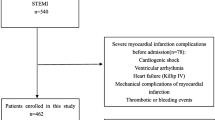

The in-hospital mortality of STEMI patients who underwent pPCI was assessed at the Department of Cardiology, Harzklinik Goslar, Germany, which has no access to immediate mechanical circulatory support (MCS), between 2013 and 2017.

Results

We enrolled 312 STEMI patients, with a mean age of 67.1 ± 13.4 years, of whom 211 (68%) were male. In-hospital mortality was documented in 31 patients (10%). In-hospital mortality was associated with pre-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR; n = 39/12.5%), older age, lower systolic blood pressure, Killip class > 1, triple-vessel disease (each p < 0.0001), female gender (p = 0.0158), and with the localization of the treated culprit lesion in the left main coronary artery (LMCA; p = 0.0083) and in the ramus circumflexus (RCX; p = 0.0141).

Conclusion

In this monocentric cohort, all-cause in-hospital mortality of STEMI patients after pPCI was significantly higher in those patients with culprit lesions in the LMCA and in the RCX, which may prove to be a substantial novel risk factor for STEMI-related mortality. Increasing age and female gender may be interdependent risk factors for mortality in this patient population. Furthermore, our data highlight the importance of the availability of MCS options in pPCI centers for patients after CPR.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Der akute Myokardinfarkt ist die hauptsächliche Ursache für die globale und die Krankenhausmortalität bei Patienten mit kardiovaskulären Erkrankungen. Ziel der vorliegenden Studie war es, die Assoziation zwischen den beteiligten Koronararterien und der Krankenhausmortalität bei Patienten mit akutem ST-Hebungs-Myokardinfarkt (STEMI) zu untersuchen, bei denen eine primäre perkutane Koronarintervention (pPCI) durchgeführt wurde.

Methoden

Die Krankenhausmortalität zwischen 2013 und 2017 wurde bei STEMI-Patienten mit Zustand nach pPCI an der kardiologischen Abteilung der Asklepios Harzklinik Goslar, die keine mechanischen Unterstützungssysteme (MCS) zur Verfügung hat, erfasst.

Ergebnisse

Es wurden n = 312 Patienten in die Studie eingeschlossen, mit einem mittleren Alter von 67,1 ± 13,4 Jahren, davon waren n = 211 (68 %) Männer. Krankenhausmortalität wurde bei n = 31 Patienten (10 %) dokumentiert. Die Krankenhausmortalität war mit den folgenden Faktoren assoziiert: präklinische kardiopulmonale Reanimation (CPR; n = 39; 12,5 %), steigendes Alter, niedriger systolischer Blutdruckwert, Killip-Klasse > 1, 3‑Gefäß-Erkrankungen (jeweils p < 0,0001), weibliches Geschlecht und Lokalisation der behandelten Zielläsion des linken Hauptstamms (LMCA; p = 0,0083) und des Ramus circumflexus (RCX; p = 0,0141).

Schlussfolgerungen

Die vorliegenden monozentrischen Daten zeigen, dass STEMI-Patienten mit Zielläsion im LMCA und im RCX eine erhöhte Krankenhausmortalität aufweisen. Dieses Ergebnis könnte einen neuen substanziellen Risikofaktor für die STEMI-bezogene Krankenhausmortalität darstellen. Zunehmendes Alter und weibliches Geschlecht könnten als voneinander abhängige Risikofaktoren für die Mortalität bei STEMI-Patienten interpretiert werden. Darüber hinaus deuten diese Daten auf die wichtige Rolle der Verfügbarkeit und Verwendung der MCS für reanimierte STEMI-Patienten in pPCI-Zentren hin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AMI:

-

acute myocardial infarction

- CAD:

-

coronary artery disease

- CRP:

-

cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- FITT-STEMI registry:

-

Feedback Intervention and Treatment Times in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction registry

- LAD:

-

left anterior descending

- LMCA:

-

left main coronary artery

- MCS:

-

mechanical circulation support

- pPCI:

-

primary percutaneous coronary intervention

- RCA:

-

right coronary artery

- RCX:

-

ramus circumflexus

- STEMI:

-

ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

References

Murray CJ, Lopez AD (1997) Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: global burden of disease study. Lancet 349(9063):1436–1442

Tsai TH, Chua S, Hussein H et al (2011) Outcomes of patients with Killip class III acute myocardial infarction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Crit Care Med 39(3):436–442

Steg PG, James SK, Atar D et al (2012) ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215

Zeymer U, Heuer H, Schwimmbeck P et al (2015) Guideline-adherent therapy in patients with acute coronary syndromes. The EPICOR registry in Germany. Herz 40(Suppl 1):27–35

Krackhardt F, Noutsias M, Tschope C, Kherad B (2017) DCB meets DES. Herz. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-016-4529-y

Nabel EG, Braunwald E (2012) A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 366(1):54–63

Simes RJ, Topol EJ, Holmes DR Jr. et al (1995) Link between the angiographic substudy and mortality outcomes in a large randomized trial of myocardial reperfusion. Importance of early and complete infarct artery reperfusion. GUSTO-I Investigators. Circulation 91(7):1923–1928

Stone GW, Grines CL, Browne KF et al (1995) Predictors of in-hospital and 6‑month outcome after acute myocardial infarction in the reperfusion era: the Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction (PAMI) trail. J Am Coll Cardiol 25(2):370–377

Yip HK, Wu CJ, Chang HW et al (2001) Comparison of impact of primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and primary stenting on short-term mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock and evaluation of prognostic determinants. Am J Cardiol 87(10):1184–1188; A4

Seghieri C, Mimmi S, Lenzi J, Fantini MP (2012) 30-day in-hospital mortality after acute myocardial infarction in Tuscany (Italy): an observational study using hospital discharge data. BMC Med Res Methodol 12:170

Hochman JS, Buller CE, Sleeper LA et al (2000) Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction--etiologies, management and outcome: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries for cardiogenic shocK? J Am Coll Cardiol 36(3 Suppl A):1063–1070

Hasdai D, Topol EJ, Califf RM et al (2000) Cardiogenic shock complicating acute coronary syndromes. Lancet 356(9231):749–756

Scholz KH, Maier SK, Jung J et al (2012) Reduction in treatment times through formalized data feedback: results from a prospective multicenter study of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 5(8):848–857

Wong SC, Sanborn T, Sleeper LA et al (2000) Angiographic findings and clinical correlates in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries for cardiogenic shocK? J Am Coll Cardiol 36(3 Suppl A):1077–1083

Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann FJ et al (2012) Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med 367(14):1287–1296

Maas AH, Appelman YE (2010) Gender differences in coronary heart disease. Neth Heart J 18(12):598–602

Kalbfleisch H, Hort W (1977) Quantitative study on the size of coronary artery supplying areas postmortem. Am Heart J 94(2):183–188

Atie J, Brugada P, Brugada J et al (1991) Clinical presentation and prognosis of left main coronary artery disease in the 1980s. Eur Heart J 12(4):495–502

Carasso S, Sandach A, Beinart R et al (2005) Echocardiography Working Group of the Israel Heart S. Usefulness of four echocardiographic risk assessments in predicting 30-day outcome in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 96(1):25–30

Hillis GS, Moller JE, Pellikka PA et al (2005) Prognostic significance of echocardiographically defined mitral regurgitation early after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 150(6):1268–1275

Zmudka K, Zorkun C, Musialek P et al (2004) Incidence of ischemic mitral regurgitation in 1155 consecutive acute myocardial infarction patients treated with primary or facilitated angioplasty. Acta Cardiol 59(2):243–244

Birnbaum Y, Chamoun AJ, Conti VR, Uretsky BF (2002) Mitral regurgitation following acute myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis 13(6):337–344

Thompson CR, Buller CE, Sleeper LA et al (2000) Cardiogenic shock due to acute severe mitral regurgitation complicating acute myocardial infarction: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. SHould we use emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries in cardiogenic shocK? J Am Coll Cardiol 36(3 Suppl A):1104–1109

Becker RC, Gore JM, Lambrew C et al (1996) A composite view of cardiac rupture in the United States National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 27(6):1321–1326

Sobkowicz B, Lenartowska L, Nowak M et al (2005) Trends in the incidence of the free wall cardiac rupture in acute myocardial infarction. observational study: experience of a single center. Rocz Akad Med Bialymst 50:161–165

French PJ, Bijman J, Edixhoven M et al (1995) Isotype-specific activation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-chloride channels by cGMP-dependent protein kinase II. J Biol Chem 270(44):26626–26631

Crenshaw BS, Granger CB, Birnbaum Y et al (2000) Risk factors, angiographic patterns, and outcomes in patients with ventricular septal defect complicating acute myocardial infarction. GUSTO-I (Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Coronary Arteries) Trial Investigators. Circulation 101(1):27–32

McNamara RL, Kennedy KF, Cohen DJ et al (2016) Predicting in-hospital mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 68(6):626–635

Iqbal MB, Nadra IJ, Ding L et al (2017) Culprit vessel versus multivessel versus in-hospital staged intervention for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease: stratified analyses in high-risk patient groups and anatomic subsets of nonculprit disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 10(1):11–23

Thiele H, Desch S, Piek JJ et al (2016) Multivessel versus culprit lesion only percutaneous revascularization plus potential staged revascularization in patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: Design and rationale of CULPRIT-SHOCK trial. Am Heart J 172:160–169

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

M. Ali is the local p.i. of the FITT-STEMI registry at the Department of Cardiology, Asklepios Harzklinik Goslar. M. Noutsias has received grants by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through the Sonderforschungsbereich Transregio 19 “Inflammatory Cardiomyopathy” (SFB TR19) (TP B2), and by the University Hospital Gießen and Marburg Foundation Grant “T cell functionality” (UKGM 10/2009). M. Noutsias has been consultant to the IKDT (Institute for Cardiac Diagnosis and Therapy GmbH, Berlin) 06/2004-06/2008, and has received honoraria for presentations and/or participated in advisory boards from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Fresenius, Miltenyi Biotech, Novartis, Pfizer and Zoll. S.A. Lange, T. Wittlinger, G. Lehnert, and A.G. Rigopoulos declare that they have no competing interests.

The clinical data of the patients, including the Killip class on admission, were computed within the framework of the FITT-STEMI (Feedback Intervention and Treatment Times in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) project, which is conducted as a multicenter registry for the evaluation of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in STEMI patients (http://www.fitt-stemi.com/). The study was approved by the local ethics committee, and all included patients signed informed consent.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, M., Lange, S.A., Wittlinger, T. et al. In-hospital mortality after acute STEMI in patients undergoing primary PCI. Herz 43, 741–745 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-017-4621-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-017-4621-y

Keywords

- Culprit lesion

- ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

- Percutaneous coronary intervention

- Hospital mortality

- Prognosis