Abstract

Background

Early reperfusion of the coronary artery has become the first choice for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). How to deal with patients who miss the time window for early reperfusion is still controversial. Based on real-world data, this study was conducted to explore whether percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has an advantage over standard drug therapy in patients who miss the optimal treatment window.

Methods

Consecutive patients who were diagnosed with STEMI and met the inclusion criteria between 2009 and 2018 in our center were retrospectively included in this cohort study. The primary endpoint events were major adverse cardiac events (MACEs), including heart failure, sudden cardiac death, malignant arrhythmia, thrombi and bleeding events during the period of admission. Secondary endpoint events were components of MACEs. At the same time, we also evaluated angina pectoris at admission and discharge through Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) grading.

Results

This study enrolled 417 STEMI patients and divided them into four groups (PCI < 3 days, 14.87%; 3 days<PCI < 7 days, 21.104%; PCI > 7 days, 34.29%; MED, 29.74%). During the period of admission, MACEs occurred in 52 cases. The incidence of MACEs was 11.29, 7.95, 4.20 and 25.81% in the four respective groups (p < 0.0001). The MED group had higher rates of MACEs (OR = 3.074; 95% CI 0.1.116–8.469, p = 0.03) and cardiac death (OR = 3.027; 95% CI 1.121–8.169, p = 0.029) compared to the PCI group. Although both treatments were effective in improving CCS grade at discharge, the PCI group improved more significantly (p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

In the real world, delayed PCI can be more effective in patients with angina symptoms at discharge and reduce the incidence of MACEs and cardiac death during hospitalization. The timing of intervention was independent of the occurrence of MACEs during hospitalization and of improvement in symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

STEMI is on the rise in China, and the turning point in cardiovascular events has not occurred yet. Optimal treatment for STEMI includes early reperfusion or thrombolytic therapy. This is the cornerstone of contemporary treatment of STEMI, preventing myocardial necrosis and its consequences. Considering the current national conditions in China, it is difficult to carry out thrombolysis in primary hospitals [1,2,3]. After being transferred to the chest pain center [4], many patients miss the optimal PCI time or even refuse PCI. In contrast to developed countries [5, 6], approximately one-third of eligible patients receive primary PCI [7]. The rest are treated with either delayed PCI or conservative medication.

There is no definitive treatment strategy for STEMI patients who miss the optimal PCI window. Previous studies have shown that delaying PCI may be effective in maintaining cardiac function and improving cardiac remodeling in patients and can effectively alleviate electrophysiological disorders [8,9,10,11]. There have been some large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that have challenged these ideas, and even though they have had similar experimental designs, they have had completely opposite results [12,13,14,15,16]. From the perspective of clinical analysis, their conclusions are very meaningful. The root cause is that RCT screening is so rigorous that the results apply only to a subset of the population. Therefore, these conclusions cannot be widely extended to clinical practice. Due to the sparse data from the real-world setting, the optimal management strategy for delayed patients with STEMI remains controversial. The aim of this study was to explore whether PCI has an advantage over standard drug therapy in a cohort of STEMI patients who miss the optimal treatment window based on real-world data from Hangzhou First People’s Hospital.

Methods

Study population

We retrospectively included all consecutive patients referred to Hangzhou First People’s Hospital for further treatment of myocardial infarction between 2009 and 2018. Treatment decisions were made by the physician and the patient in consultation, and the procedure and location of the stent placement was entirely up to the surgeon. Patients who met the inclusion criteria but did not meet the exclusion criteria were enrolled. The enrolled patients were divided into four subgroups based on predesigned criteria. In total, we included a total of 417 patients treated with PCI or conservative medications. A flow chart illustrating the patient selection process is presented in Fig. 1.

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion

Inclusion criteria

-

The patient was diagnosed with STEMI according to the STEMI guidelines in China [17]

-

The onset of chest pain was greater than 12 h earlier

Exclusion criteria

-

Previous PCI or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) or thrombolytic therapy

-

Myocardial reinfarction

-

Severe myocardial infarction complications before admission

-

Coronary angiography followed by no stent implantation

Treatment

All patients were treated with optimal medications, including dual antiplatelet drugs (aspirin and clopidogrel), anticoagulants, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, β receptor blockers, and lipid-lowering therapy, for as long as the heart rate and blood pressure were not adversely affected, unless the use of these medications was clearly contraindicated. The clinician determined whether to give a dose of antiplatelet drugs by predicting whether the drug would reach an effective blood concentration at the time of surgery. Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) was discontinued on the morning of PCI, common heparin was used intraoperatively to maintain the patient’s activated coagulation time (ACT) level, and LMWH was continued for 3–4 days after PCI. The use of additional instruments and drugs required during the procedure was entirely up to cardiovascular interventionists, such as thrombus aspiration catheters and β2/α3 receptor blockers. When myocardial infarction was complicated with multiple lesions, the culprit diseased vessels were treated preferentially, and non-culprit lesions were treated after 1 month.

Data extraction

All blood biochemical results were obtained from the first blood samples taken within 24 h of admission. The evaluation of the coronary angiography results was performed entirely in the catheterization room by the surgeon and the first assistant. All CCS scores were assessed by the attending physician and recorded in the course of the disease. The extraction of the coronary angiography results and the CCS grades on admission and discharge were performed separately by the two authors (Qixin Guo and Yong Shen).

Endpoint

The primary endpoint events were major adverse cardiac events (MACEs), including heart failure, sudden cardiac death, malignant arrhythmia, thrombus and bleeding events during the period of admission. Secondary endpoint events were components of major adverse cardiac events. We also evaluated angina pectoris at admission and discharge through CCS grading.

Statistical analysis

Before the statistical operation, all the data were drawn into scatter graphs and tested for normality and homogeneity of variance. The main baseline characteristics of patients are described as frequencies for categorical variables and as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables (normally distributed) or median with interquartile range (not normally distributed). The means of different groups were compared by one-way ANOVA (normality and independence) or Kruskal-Wails H rank sum test (independence but not normality). The comparison of multiple rates was performed using the common chi-square test. Pairwise comparisons between the groups were performed using either the chi-square test (ordered result variable) or the Mann-Whitney U test (disordered result variable) after correcting the P value.

Before we proceeded to multifactor logistic regression, we drew directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) [18, 19] to exclude possible mediating variables (Fig. 2). Then, we screened covariables through the effect change method and imported all possible covariables into the regression equation by using the enter method. The OR value of the drug treatment compared with PCI was recorded. Each variable was removed one by one, and a regression model was constructed to obtain the OR values of different treatment methods. We removed the variable that had the least effect on the OR value, and the OR value did not change by more than 10%. One by one, other variables were eliminated in the same way until all irrelevant variables were eliminated (Table 1). Finally, the selected covariates and control variables were combined to construct the regression model [20].

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 23.0). A two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 2 summarizes baseline patient characteristics according to treatment modality and timing of intervention. The mean age was 71 years (58–79), and 68.3% of the patients were male. In the study, 58% had a medical history of hypertension, 2.6% had hyperlipidemia, and 20.9% had diabetes. Most of the patients in the MED group were elderly (compared with the other three groups, P < 0.0001). Significant differences between pairs of groups were also observed in CCS rank, UA, sex, and SCR.

Primary endpoint

During hospitalization, 52 patients (12.47%) experienced a MACE: 26 (6.23%) had heart failure, 21 (5.04%) had cardiovascular death, 2 (0.48%) had myocardial reinfarction, 7 (1.68%) had malignant arrhythmia, and 6 (1.44%) had bleeding or thrombotic events (Table 3). The incidence of MACEs was 11.29, 7.95, 4.20 and 25.81% in the four respective groups (p < 0.0001). However, in the pairwise comparison results, no significant differences were found between the three PCI subgroups (Table 4), even after group merging. The MED group had higher rates of MACEs (OR = 3.074; 95% CI 0.1.116–8.469, p = 0.03) and cardiac death (OR = 3.027; 95% CI 1.121–8.169, p = 0.029) compared to the PCI group. Ejection fraction (EF), different treatment modalities and Uric acid (UA) were independent risk factors for MACEs in hospitals, while in-hospital deaths were only correlated with age and treatment modality. No statistically significant differences were found in the exploration results for other secondary end points (details can be found in Additional file 1).

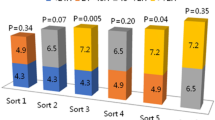

CCS classification score

There were significant differences in CCS classification at discharge and admission. When the differences between the groups were further studied, we found that there was no significant difference in CCS grade between groups 2 and 3 at admission, and the overall value was group 1 > group 4 > group 2 ≈ group 3 (Table 4). The same method was used to evaluate the CCS grade at discharge, and there was no statistically significant difference in CCS grade among the three PCI groups, with P values of 0.901, 0.468 and 0.491, respectively. The overall ranking was group 4 > group 1 ≈ group 2 ≈ group 3 (Table 4). Both conservative drug therapy and interventional therapy showed a significant decrease in CCS grading. In contrast, the interventional therapy was better alleviating patients’ subjective symptoms, but symptom alleviation had little relationship with the timing of intervention (Table 4, Fig. 3).

Discussion

The principal findings of this real-world study of patients with STEMI who exceeded the optimal reperfusion window were as follows. 1. PCI treatment significantly reduced the incidence of MACEs and deaths in the hospital compared to optimal drug therapy. 2. PCI can significantly improve the patient’s symptoms after treatment and increase the satisfaction with the outcome of hospitalization.

This study focuses on areas that currently are not specifically recommended in the guidelines. Based on the conclusions of previous RCTs, this study can be a good supplement. The study group missed the optimal reperfusion window, and most of the patients still had significant angina symptoms when admitted to the hospital. The disease may deteriorate at any time. For these patients, the use of reperfusion therapy as soon as possible may be able to successfully protect the patient through the crisis period. The clinician’s focus on when reperfusion offers the greatest long-term benefit may actually increase the patient’s risk. It is theoretically and ethically impossible to include this population in RCTs. The results from observational studies have high intrinsic validity and can provide important references for clinical practice.

The current guidelines recommend direct PCI for STEMI patients with chest pain up to 12 h, with the indication extending up to 48 h in some patients [21, 22]. Residual anterograde coronary artery blood flow and reverse collateral circulation after myocardial infarction can ensure the survival of myocardial hibernating and myocardial suppressed cells, and saving these cells may prevent myocardial remodeling and electrophysiological disorders [21]. Such a pathophysiological basis may explain the appropriate relaxation of the treatment window for STEMI. The late open artery theory holds that the removal of vascular obstruction can improve the prognosis of patients. However, the results of a series of studies at OAT do not support this theory. The reasons for the different conclusions between the OAT study and other studies are as follows: 1. the baseline characteristics of the included populations are significantly different, and the time span of the population stratification is too large; 2. interventional devices and drugs have been updated; and 3. the patients enrolled in the OAT trial adhered to the ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of STEMI. Optimal drug regimens and careful management make the difference difficult to observe.

The detailed division of the definition of myocardial infarction contributed to the accuracy of the study. Recent research on non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome showed that the delayed group did not have an increased adverse prognosis compared to the early intervention group [22], but it was significantly better than conservative treatment [23]. Depending on the pathophysiology of different myocardial infarction types, the changes in nosocomial conditions and long-term prognosis are totally different [24]. Our study found that although PCI significantly improved the incidence of endpoint events, there was no difference between the time groups of different interventions, which is inconsistent with previous research conclusions [25, 26]. The combination of the PCI < 3 days group and the 3 days<PCI < 7 days group was compared with the PCI > 7 days group, and no significant results were obtained. This may be due to the limited number of cases and lack of long-term outcomes. In summary, based on the current evidence-based medical evidence, as an important influencing factor, PCI was performed within 3 days for patients whose condition might change in a short period of time and after 7 days for patients whose condition was relatively stable, which strongly correlated with the improvements of in-hospital events.

Limitation

The present study has the following limitations: 1. this study is a single-center retrospective cohort study, the sample size is not large enough, and the exact results need to be supported by large-database studies. In addition, the retrospective nature of our study ensures that the results cannot be conclusive. 2. Many patients in our center were referred by local hospitals, which may result in deviations and partial data loss. For example, many patients in the group with PCI > 7 days were treated locally and transferred to our hospital for interventional surgery after stabilization. 3. During treatment, some patients were transferred to other hospitals for treatment or discharged automatically with unknown results. 4. Finally, we lost the follow-up records for our patients when we moved. Further research should focus on two areas. The first is to continue to follow up the patients and fill in the missing data. Survival analysis may yield more accurate results. Second, as cardiac intervention instruments and drugs are updated, large multicentric RCTs are also needed to guide the current treatment strategies.

Conclusions

In the real world, our data suggested that delayed PCI can be more effective in patients with angina symptoms at discharge and reduce the incidence and MACEs and cardiac death during hospitalization. The timing of intervention was independent of the occurrence of MACEs during hospitalization and of the improvement in symptoms. We recommend further clinical trials to confirm this conclusion.

Availability of data and materials

All data that support the findings of this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files]. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- STEMI:

-

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- MACEs:

-

Major adverse cardiac events

- CCS:

-

Canadian cardiovascular society

- RCTs:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass graft

- LMWH:

-

Low-molecular-weight heparin

- ACT:

-

Activated coagulation time

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- DAG:

-

Directed acyclic graphs

- EF:

-

Ejection fraction

- UA:

-

Uric acid

References

Feng L, Li M, Xie W, Zhang A, Lei L, Li X, Gao R, Wu Y. Prehospital and in-hospital delays to care and associated factors in patients with STEMI: an observational study in 101 non-PCI hospitals in China. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e031918.

Li X, Li J, Masoudi FA, Spertus JA, Lin Z, Krumholz HM, Jiang L. China PEACE risk estimation tool for in-hospital death from acute myocardial infarction: an early risk classification tree for decisions about fibrinolytic therapy. BMJ Open. 2016;6(10):e013355.

Li J, Li X, Wang Q, Hu S, Wang Y, Masoudi FA, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM, Jiang L. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in China from 2001 to 2011 (the China PEACE-retrospective acute myocardial infarction study): a retrospective analysis of hospital data. Lancet. 2015;385(9966):441–51.

Peng YG, Feng JJ, Guo LF, Li N, Liu WH, Li GJ, Hao G, Zu XL. Factors associated with prehospital delay in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction in China. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(4):349–55.

Kim BW, Cha KS, Park MJ, Choi JH, Yun EY, Park JS, Lee HW, Oh JH, Kim JS, Choi JH, et al. The impact of transferring patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction to percutaneous coronary intervention-capable hospitals on clinical outcomes. Cardiol J. 2016;23(3):289–95.

McDermott K, Maynard C, Trivedi R, Lowy E, Fihn S. Factors associated with presenting >12 hours after symptom onset of acute myocardial infarction among veteran men. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2012;12:82.

Huo Y. Current status and development of percutaneous coronary intervention in China. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2010;11(8):631–3.

Abbate A, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Appleton DL, Erne P, Schoenenberger AW, Lipinski MJ, Agostoni P, Sheiban I, Vetrovec GW. Survival and cardiac remodeling benefits in patients undergoing late percutaneous coronary intervention of the infarct-related artery: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(9):956–64.

Zeymer U, Uebis R, Vogt A, Glunz HG, Vohringer HF, Harmjanz D, Neuhaus KL, Group AL-S. Randomized comparison of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and medical therapy in stable survivors of acute myocardial infarction with single vessel disease: a study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische Krankenhausarzte. Circulation. 2003;108(11):1324–8.

Horie H, Takahashi M, Minai K, Izumi M, Takaoka A, Nozawa M, Yokohama H, Fujita T, Sakamoto T, Kito O, et al. Long-term beneficial effect of late reperfusion for acute anterior myocardial infarction with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Circulation. 1998;98(22):2377–82.

Erne P, Schoenenberger AW, Burckhardt D, Zuber M, Kiowski W, Buser PT, Dubach P, Resink TJ, Pfisterer M. Effects of percutaneous coronary interventions in silent ischemia after myocardial infarction: the SWISSI II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297(18):1985–91.

Menon V, Pearte CA, Buller CE, Steg PG, Forman SA, White HD, Marino PN, Katritsis DG, Caramori P, Lasevitch R, et al. Lack of benefit from percutaneous intervention of persistently occluded infarct arteries after the acute phase of myocardial infarction is time independent: insights from occluded artery trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(2):183–91.

Hochman JS, Lamas GA, Buller CE, Dzavik V, Reynolds HR, Abramsky SJ, Forman S, Ruzyllo W, Maggioni AP, White H, et al. Coronary intervention for persistent occlusion after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(23):2395–407.

Kruk M, Buller CE, Tcheng JE, Dzavik V, Menon V, Mancini GB, Forman SA, Kurray P, Busz-Papiez B, Lamas GA, et al. Impact of left ventricular ejection fraction on clinical outcomes over five years after infarct-related coronary artery recanalization (from the occluded artery trial [OAT]). Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(1):10–6.

Malek LA, Reynolds HR, Forman SA, Vozzi C, Mancini GB, French JK, Dziarmaga M, Renkin JP, Kochman J, Lamas GA, et al. Late coronary intervention for totally occluded left anterior descending coronary arteries in stable patients after myocardial infarction: results from the occluded artery trial (OAT). Am Heart J. 2009;157(4):724–32.

Lang IM, Forman SA, Maggioni AP, Ruzyllo W, Renkin J, Vozzi C, Steg PG, Hernandez-Garcia JM, Zmudka K, Jimenez-Navarro M, et al. Causes of death in early MI survivors with persistent infarct artery occlusion: results from the occluded artery trial (OAT). EuroIntervention. 2009;5(5):610–8.

China Society of Cardiology of Chinese Medical Association. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2010;38(8):675–90.

Textor J, Hardt J, Knuppel S. DAGitty: a graphical tool for analyzing causal diagrams. Epidemiology. 2011;22(5):745.

VanderWeele TJ, Hernan MA, Robins JM. Causal directed acyclic graphs and the direction of unmeasured confounding bias. Epidemiology. 2008;19(5):720–8.

Greenland S. Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(3):340–9.

Sim DS, Jeong MH, Ahn Y, Kim YJ, Chae SC, Hong TJ, Seong IW, Chae JK, Kim CJ, Cho MC, et al. Benefit of percutaneous coronary intervention in early latecomers with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(9):1275–81.

Yudi MB, Ajani AE, Andrianopoulos N, Duffy SJ, Farouque O, Ramchand J, Gurvitch R, Lefkovits J, Freeman M, Brennan A, et al. Early versus delayed percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes. Coron Artery Dis. 2016;27(5):344–9.

Kvakkestad KM, Gran JM, Eritsland J, Holst Hansen C, Fossum E, Andersen GO, Halvorsen S. Long-term survival after invasive or conservative strategy in elderly patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a prospective cohort study. Cardiology. 2019;144(3–4):79–89.

Park HW, Yoon CH, Kang SH, Choi DJ, Kim HS, Cho MC, Kim YJ, Chae SC, Yoon JH, Gwon HC, et al. Early- and late-term clinical outcome and their predictors in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2013;169(4):254–61.

Alexander T, Mullasari AS, Joseph G, Kannan K, Veerasekar G, Victor SM, Ayers C, Thomson VS, Subban V, Gnanaraj JP, et al. A system of Care for Patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in India: the Tamil Nadu-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction program. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(5):498–505.

Zheng W, Yu CM, Liu J, Xie WX, Wang M, Zhang YJ, Sun J, Nie SP, Zhao D. Patients with ST-segment elevation of myocardial infarction miss out on early reperfusion: when to undergo delayed revascularization. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14(8):524–31.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the head of statistics department of Zhejiang university of traditional Chinese medicine for the statistical guidance.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JYH provided the general direction of the thesis, while QXG mainly completed data extraction, statistical analysis and article writing. YS, GXT, HL and SSM provide their own Suggestions for revision when writing is completed. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

We declare that we do not have any commercial or associative-interest that represents a conflict of interest in connection with the work submitted.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, Q., Huang, J., Shen, Y. et al. The role of late reperfusion in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a real-world retrospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 20, 207 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01479-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01479-0