Abstract

Background

As digital technology presents the potential to enhance the accessibility and effectiveness of health promotion campaigns, adolescents and young adults are an important target population. Young people are establishing behaviors that will contribute to the quality of their health later in life, and thus understanding their particular perspectives and receptivity to digital technologies for health promotion is crucial. With this review we aimed to synthesize the published literature reporting perspectives on digital health promotion (DHP) from adolescents and young adults worldwide.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review of the literature on five research databases. We included papers which defined a target population of young people, and encompassed qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies. Two independent reviewers thematically analyzed the included publications and provided both a quantitative and a narrative synthesis of the views of youth (namely opportunities and concerns) on digital health promotion.

Results

We retrieved and analyzed 50 studies which met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. The large majority of these studies were conducted in high-income countries, while only a few collected the perspectives of youth in low- or middle-income countries. Findings revealed the importance of certain technology features, such as user interface design, as well as the significance of lack of personalization or user experience friction, for example, as deterrents to engagement with DHP tools. Ethically relevant aspects, such as those related to privacy or scientific reliability of the tools, did not receive much attention from youth. Yet, DHP for particularly sensitive areas of health elicited more frequent concerns about data security and evidence of effectiveness.

Conclusions

Young people express distinct opinions and preferences concerning the use of digital technologies for health promotion. Our review identified a general appreciation and receptivity on the part of adolescents and young adults towards these technologies, even when taking potential risks into account.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Digital technology is transforming the field of health promotion, making traditional health services and public health campaigns more accessible and effective worldwide. A growing body of literature supports this claim, and reports on mobile applications, wearable devices, social media, and AI-powered chatbots becoming viable health promotion tools [1,2,3]. There are an especially large number of digital health promotion (DHP) strategies targeting younger generations [4, 5]. By addressing health issues at an early age, minimizing exposure to risk factors (e.g., tobacco, alcohol, interpersonal violence), and heightening protective factors (e.g., physical activity, healthy diet, positive mental and sexual health), wellbeing can be maintained throughout life. Not only will this benefit youth in the present, but will create a more healthful adult society in the future. Thus, WHO and other health institutions worldwide have encouraged the adoption of these tools, to expand health services and improve global health [6, 7].

Young people seem to be increasingly comfortable with technology compared to older generations, and eager to receive the benefits offered by a globalized and ever-evolving world [8]. We are witnessing a worldwide increase in the adoption of digital tools (like smartphones) and in digital literacy skills among youth. A growing number of examples show that young people in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) are willing to harness existing technologies (such as texting apps, social media platforms and web interactive programs) to maintain or improve their health status [9, 10]. Youth are drawn to the benefits of DHP, such as: expanded availability of health promotion services (beyond traditional formats, times and locations); confidential connections with peers and experts without the need to physically interact with health professionals; personalized support for behavior change through engaging visualizations and gamification strategies; and cost-effectiveness [11]. As DHPs espouse the concepts of autonomy and individual agency in taking responsibility and care for one's own health, these digital solutions and direct-to-consumer products can benefit many young people, especially in contexts where primary healthcare services are lacking.

Yet, access to technologies and digital literacy alone may not be sufficient to establish digital agency and confidence to adopt these tools [12, 13]. Recent research has reported on the ethical, social, and regulatory challenges of implementing DHP for young people. Access, equity, privacy, confidentiality, individual responsibility, and accountability must all be taken into account [14]. Who is responsible for providing access to these technologies in countries with a digital divide and among population segments with lower levels of digital literacy? Are the advantages of using DHPs shared fairly among stakeholders? Are the captured data stored securely and used responsibly, and by whom? Also, what role do governments and health institutions play if individuals are increasingly expected to take responsibility for their own health? Finally, digital platforms and direct-to-consumer technologies fall outside the purview of oversight and governance mechanisms which regulate medical devices. Therefore, who is accountable for faulty technologies or misleading information provided by DHPs?

With interest in this field on the rise, there are an increasing number of reports calling for the involvement of younger people in the development of health technologies. For example, the WHO’s "Youth-centred digital health interventions" document emphasizes the urgency of identifying possibilities and problems posed by new technologies from the perspective of young people in various parts of the world [15]. Similarly, the Lancet and Financial Times initiative "Growing up in a digital word" aims to build a youth network to guide the development of technologies, as inspired by the needs of young people [16]. These efforts demonstrate the intentions of both international and local health institutions to realize the power of digital technologies to accelerate progress towards responsible global health and better health for all (as prescribed by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3) [17,18,19].

While in recent years researchers have engaged young people and gathered their views and opinions on DHP strategies, a synthesis of these perspectives is still missing. Existing systematic reviews describe the effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility of DHP strategies for promoting youth health [20, 21]. Review topics range from sexual and reproductive health [22] to mental health [23] and nutrition and physical activity [24, 25], with several studies focused on youth in LMICs [2, 26, 27]. However none of these projects thoroughly examined the nuanced opinions and perspectives of young people regarding the strengths and weaknesses of DHP tools. The objective of this scoping review is thus to systematically examine the published literature discussing young people's perspectives on the benefits, opportunities, and positive features of DHPs, as well as the shortcomings.

Methods

Scoping review of the literature

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to explore the opinions and views of young people about digital health promotion in a comprehensive way. Through this scoping review we aim to map emerging evidence and types of data available to better understand the complex field of DHP, identify ethical considerations, and detect potential gaps in the literature, so as to inform future research. Scoping review as a methodology, as precursor to systematic literature review, investigates broader research questions, and can uncover key features of emerging fields that have not been examined in depth [28].

Eligibility for inclusion

We built our search string and inclusion/exclusion criteria aiming to gather the academic literature currently available to address our research question. The detailed search strategy is available in supplemental material 1 and a detailed list of the inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in supplemental material 2. We chose to focus on the target population of adolescents and young adults (AYAs), excluding children and adults in general. The WHO defines AYAs (also known as young people) as individuals aged between 10 and 24 years old. Yet the definition of young people or youth across international organizations and countries is quite flexible, and can include individuals up to 30 or 35 years of age [29]. Thus, we included in our review all papers that focused on AYAs or that specifically defined the target population as youth or young people.

We included primary qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research studies discussing health promotion interventions. Building on the WHO Ottawa Charter of Health Promotion, we defined health promotion as an intervention that engages individuals in maintaining good health conditions by minimizing health risk factors and optimizing protective ones [30, 31]. We therefore focused our review only on primary prevention among young people in a typical state of health, in which the user is actively engaged to understand a health topic or modify their behavior, and excluded studies about secondary prevention or focused on individuals with existing conditions [32]. We included health promotion activities in the form of digital tools (e.g., web platforms, chatbots, social media, mobile apps, wearable devices, messaging), excluding treatment and telemedicine interventions. Included papers were published since 2007 (as the year in which the wording “mhealth” was coined [33]), and reported young people’s perspectives from primary sources (such as via interviews, surveys, questionnaires, or focus groups). Papers reporting the opinions of parents or caregivers, rather than young people themselves, were excluded. Studies published in English, German, Italian, French, or Spanish were eligible for review.

Literature search

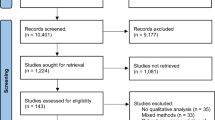

Conducted on the 24th of May 2022, our initial search of five research databases (Embase, Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, and PsychInfo) retrieved 755 papers, which were uploaded to Rayyan, a web-based tool for systematic reviews [34]. 382 results were then excluded as duplicates, and a further 58 excluded due to missing publication date or author, or being published prior to 2007. 315 study abstracts were screened for inclusion. Of these, 256 were excluded as not meeting the criteria to answer our research question.

We then looked for the full text of the 59 remaining papers which qualified for study inclusion. Four of these papers could not be retrieved and were excluded. Finally, 55 papers were included in our scoping review. Please see Fig. 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram describing our process for identifying included papers.

Data extraction

A Microsoft Excel data extraction sheet was created based on an initial reading of study abstracts and deductive definition of fields relevant to our research question. The data extraction field was subsequently updated to include new themes identified inductively by screening a sample of ten publications [35]. Two reviewers (AF, SH) examined the full text of the 55 included papers and extracted information describing the characteristics of young people’s views on the use of digital means for health promotion. In case of misalignment of opinions, the two reviewers discussed the paper in question and came to an agreement. Upon review, five of these papers were excluded because they did not match inclusion criteria, leaving a total of 50 papers for inclusion in the review (the full list of included papers is available in supplemental material 3 and 4, as well as the PRISMA-ScR checklist for scoping reviews can be found in supplemental material 5). After data extraction from 50 articles was complete, frequency was totaled for each field, to begin to identify trends in our results.

Results

General findings

Of the 50 papers included in our review, nine (18%) reported opinions of young people in LMICs [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44], while the majority (82%) of studies were conducted in HICs (Fig. 2). Most publications from HICs were based in the US (n = 15), followed by the UK (n = 7) and Australia (n = 6). Twenty-six papers (52%) presented mixed-methods research, while 22 (44%) reported on qualitative research and two publications presented entirely quantitative studies (survey studies). Most studies used either interviews or focus groups to collect AYA’s perspectives; only a minority (24%) adopted closed-question surveys, alone or in combination with other methods.

The majority of included papers (n = 23; 46%) focused on young adults (individuals aged approximately 19 to 30 years) while 19 papers (38%) focused on adolescents (10 to 19 years of age). Fewer papers addressed young people more broadly, from adolescence into young adulthood (Fig. 3).

In 33 studies (66%), researchers invited young people to share their opinions and feedback on a specific DHP intervention, compared with 17 studies which solicited general views on digital health promotion tools. Studies explored a variety of areas of AYA health, including physical activity and nutrition (30%), sexual and reproductive health (28%), mental health (22%), general health and fitness (12%), and substance abuse prevention (e.g., smoking cessation, prevention of alcohol and drug abuse) (8%) (Fig. 3). Publications from LMICs explored DHP applications related to sexual and reproductive health or physical health and nutrition.

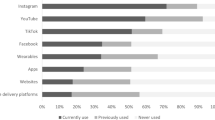

Publications reported on a variety of DHP formats, including mobile applications (56% of papers), social media (44%, with Facebook mentioned most frequently, followed by YouTube and Instagram), web-based services (apps, chatbots, platforms, and webpages) (30%), SMS and phone calls (14%), wearables (e.g., Fitbit) (4%), and virtual reality (2%.) The most frequently mentioned features of DHP included text, audio, video, images, peer support, and gamification (Fig. 4).

Our age group analysis showed a correlation between young adults and the use of mobile apps for DHP, while social media and SMS were more commonly mentioned among adolescents. While the peer coaching and support feature was raised more frequently by young adults, adolescents highlighted the role of gamification in DHP interventions. Studies addressing a broader age range reported on the relevance of text and video features. (Fig. 4).

In general, more positive attributes of DHP were cited than negative ones, though drawbacks were often described in greater detail. We did not observe a noticeable difference between age groups in reflections on the strengths and weaknesses of DHP.

Benefits and positive characteristics

Adolescents and young adults described features of DHP tools that appealed to them as users (Fig. 5a.) First and most commonly, young people valued the quality of user interface design. Namely they appreciated a format that is easy, clear, understandable, and visually appealing and engaging (80%). Our findings indicated that AYA value visually appealing DHP tools, with a user-friendly interface and good visuals (i.e., casual tone, appealing colors, attractive presentation, instrumentally engaging) described as factors encouraging engagement [40, 45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. For instance, humor and a fun yet respectful tone were appreciated as making health promotion messages more engaging [37, 39, 47, 52, 53], together with content that is instructive and well-structured [53, 54]. In general, brief and direct information was perceived by AYA to improve the accessibility of health promotion initiatives. AYA recognized health promotion technology as offering a single source of comprehensive information in one place [40, 53], and valued the quality of inclusion in DHP applications, for example across genders and sexual orientations [45, 49].

Secondly, young people identified DHP as a supplemental support to their personal efforts for maintaining good health (74%). Technology for health promotion can be accessed at a time and place of the user’s choosing, and respondents identified this a-synchronicity as better enabling connectivity [40, 50, 55, 56]. DHP was seen as non-judgmental, a particularly relevant point for health topics with potential stigma attached, as well as offering freedom of learning, at a low cost or free of charge [44, 46, 57, 58]. Young people find DHP tools to potentially expand access to health promotion to a broader population [53], as youth are increasingly reachable via technology, and at a faster pace than traditional campaigns.

Informative and personalized content enabled by DHP was also appealing to youth (74%). Young people commented on the potential of DHP to offer interesting and educational content which raises awareness of important topics [51, 59]. The possibilities to receive coaching or to learn from characters’ stories were noted as appealing features, with the ability to customize content and check personal progress identified as motivating and encouraging, and enabling engagement over the longer term [50, 54, 60,61,62,63]. AYA saw DHP as offering the possibility to learn something new about oneself.

Young people placed a high value on connecting with others to discuss health topics and expressed the appeal of a sense of community when utilizing technology for health (62%.) Sharing one’s experiences, and receiving feedback and encouragement from others, were associated with positive feelings among users, with the knowledge gained then incorporated into everyday life [38, 62, 64]. AYA reported the quality of social connection as encouraging them to consider the relevance of health issues more closely, and raising awareness among peers [52, 65,66,67].

Young people reflected on the effectiveness of DHP for supporting behavior change and increasing confidence in their health choices (54%). Receiving feedback on one’s progress, and recognition of improved personal health behaviors after engagement with health promotion technology, were mentioned as positive aspects [41, 44, 67,68,69,70,71]. Finally, DHP technology offered young people the benefit of privacy and confidentiality (36%), allowing users to be open and honest about matters of health, and reducing the need to engage with a healthcare professional face to face [38, 68, 70, 72, 73].

Concerns and weaknesses

Young people also recognized concerns and potential drawbacks of engaging with DHP (Fig. 5-a.) First, there was concern over user experience frictions leading to cumbersome DHP tools (58%.) AYA raised several related issues, including poor technology infrastructure (system crashes, tools draining phone battery), time-consuming design demanding excessive clicking and input of information, and a high level of complexity in a tool’s functioning [37, 50, 59, 60, 63, 64, 74]. This is a particular concern for those with a lower level of digital skills, with access to health promotion potentially limited as a result. Concern over the time required to engage with DHP technology was also identified by AYA [46, 54, 71]. If too much or too frequent input (e.g., notifications) is received, DHP risks becoming more tedious than practical. Content should be concise and to the point, to avoid boredom and disengagement among users [61] (Fig. 5-a). Young people indicated a wish for the ability to enter data accurately into a health promotion app, with a lack of correct options for input as discouraging use of a platform [54, 75, 76].

A lack of personalization in DHP tools was named as a deterrent to user engagement (42%). This could be a consequence of inadequate testing among the target group (e.g., user experience design), which risks development of an end product that is less appealing or engaging for young people, is redundant relative to other tools, or does not address the true needs of this population [50, 61, 71, 72, 77,78,79]. These are inherent risks when digital health technology is provided from a top-down approach, such as a health promotion initiative created by public health authorities that has not first been trialed among AYA for feedback. Information provided by DHP tools was at times considered irrelevant in a user’s specific context [62, 76]; integration of DHP into local health services was suggested as a further way to address this disconnect [78].

Young people expressed concern over privacy risks as leading to potential stigmatization associated with using digital tools for health promotion (34%). AYA reflected on the risk of embarrassment if their personal data were to be shared [72, 74]. For this reason, many opposed linking DHPs to social media [53, 60, 80]. A further concern was that the quality of user anonymity on a platform could allow for irresponsible use, increasing the risk of cyberbullying [47, 79, 81]. Violations of privacy were reported as a greater concern for young adults compared with adolescents (Fig. 5-a).

Less frequently, AYA identified the inherent lack of human interaction in DHP technology as a drawback (22%). Trusting relationships are more difficult to build via technology, and technology was perceived as lacking empathy when it comes to complex or sensitive matters of personal health [68, 72, 82]. The absence of body language can lead to confusion or misinterpretation in communication, and the absence of human interaction can shift the burden of discerning the reliability of information to young people [75, 83]. AYAs also reflected that technology may complement but cannot replace the role of humans in fostering good health [38, 62, 66, 84].

The risk for misinformation in DHP was recognized [53], with the corresponding result of misguided health choices (22%). Youth shared concerns over the possibility for inaccurate content [66, 68, 71, 74], and the questionable role of influencers who are not experts in health or medicine [81, 85]. Finally, young people recognized the potential lack of effectiveness of DHP (10%.) Some found information and sources to support health claims to be missing, and felt the need for more scientific evidence, for example, in the form of statistics and data [67, 75]. Questions of effectiveness were raised by some young people who did not experience an anticipated change (e.g., reduced stress levels) after engaging with DHP [86].

Regarding AYA views about the strengths and weaknesses of DHP in relation to the various areas of health (Fig. 5b), we noted the perception of the potential for DHP to provide support beyond traditional strategies for good health, and to build communities and a sense of belonging. This was particularly relevant for the areas of mental health and substance abuse prevention, such as tobacco or alcohol consumption. Moreover, young people reflected positively on the perceived effectiveness of DHP for behavior change in the areas of physical health and nutrition, as well as mental health and substance abuse prevention.

Regarding privacy and confidentiality concerns, AYAs generally held a positive opinion for DHPs addressing the area of mental health. However, in the areas of sexual and reproductive health and substance abuse prevention, privacy and the risk for stigma were more primary concerns. Privacy was rarely mentioned in the fields of physical activity, nutrition, and fitness, whereas in these areas, concerns were related to the lack of human interaction and time required to engage with DHP.

Discussion

This review allowed us to summarize the existing literature on young peoples’ views about digital technologies for health promotion, exploring particularly what excites and alarms them. Our findings point toward a general receptiveness among youth towards DHP, who see technology as an opportunity to extend the reach of traditional healthcare services. This positive opinion is consistent with recent research reflecting youth's optimistic outlook and appreciation of technology, even in light of potential risks [8].

However, we should stress that most of the studies included in this review focus on AYAs from the global North. Therefore, the voices of young people from less developed countries are only partially represented in these results. This could indicate that DHP is not widespread in LMICs, or that little research has been conducted so far to gather the views of youth in these settings. However, we should expand research in this area, as AYAs make up a large proportion of the population in LMICs and are increasingly using DHP. In Kenya for example, almost 60% of the population is under 24 years old, and more than 45% of young people between the ages of 15 and 24 use the internet every day [8]. Otherwise, the priorities and needs of youth in these settings may remain misunderstood and underestimated. As a result, DHP would fail to reach its full potential.

Privacy is a key issue in digital health literature in general. However, the present study reveals that young people do not perceive this topic as particularly relevant when reflecting on DHP [87]. Adolescents in particular tended to pass over the topic. More generally, we note that young people's comments indicate a moderate view of privacy, without emphasizing it as either a strength or a weakness of DHP. However, some areas of health that deal with particularly sensitive data (such as mental health, sexual reproductive health, or substance abuse prevention) engender stronger views about data security and anonymization. From this analysis, we draw two conclusions. First, although the issues of data confidentiality and protection are not prominently debated among young people, tech developers and institutions should not overlook them when developing technology. AYA's nominal interest in this area may be related to low awareness of the implications and risks of privacy breaches, and the conditions in which their data may be used and shared by public and private entities. Second, the sensitivity of the area of health content of a DHP platform is of great relevance to young users. So, it is imperative to create private and confidential spaces, to ensure that young people feel safe and protected while sharing questions, opinions, and concerns about potentially socially stigmatizing topics such as sexual transmittable diseases, substance abuse, or mental health problems.

The conventional criticisms of DHPs, as lacking solid evidence of effectiveness and increasing the spread of dangerous misinformation, have no significant presence in our findings. When young people are asked about the strengths and limitations of DHPs, they address these topics only superficially. However, this result could be attributed to the fact that young people are still developing the health literacy and fact-checking skills necessary to distinguish between good and bad resources and services. This interpretation is supported by the fact that AYAs themselves comment on DHP services being at times too complex for their digital or scientific knowledge. Therefore, it is crucial to invest in young people's digital and health literacy, to encourage them to become more independent and knowledgeable users of technology. That said, this approach of strengthening individual skills should not replace institutional efforts to ensure health promotion interventions are made available together with evidence.

Issues of cost and socio-cultural barriers as impeding access to technology are discussed only occasionally. This may be due to our analysis of a sample of studies that are not representative of a number of ethnic and socio-economic groups, especially in LMICs. Furthermore, most of the studies evaluated the effectiveness of specific DHP interventions, in which participants were given access to the service or device being tested. Without measuring contextual barriers at a regional or community level (e.g., lack of infrastructure, apps not free of charge, high data plan costs, low health and digital literacy, unmet basic needs), these studies may not reflect the realities of life faced by many AYAs. Nevertheless, the findings may still be sound for high-income countries, where recent research shows that over 90% of young people have daily access to the internet [8].

Finally, AYAs call for a personalized response to their needs and questions. This feature sets DHP apart from traditional health promotion campaigns, with messages standardized across recipients [88]. However, our findings also demonstrate that alongside tailored responses, AYAs seek connection (e.g., among peers) in DHPs, and communities where they can identify and feel understood. This review therefore emphasizes the need for appropriately balanced digital promotion approaches, that are simultaneously customized to individuals yet also convey messages applicable across communities. To find the sweet spot between these two dimensions, DHP developers and promoters should better engage with youth. In both the design and implementation phases of digital health promotion strategies, young people should have the opportunity to express their needs and expectations. DHP should result from a co-creative process that places young people at the center and allows them to provide valuable input.

Limitations

In the publications included in our review, Facebook was the most frequently mentioned form of social media for DHP [41, 42, 47, 79, 89]. Recent data on youth communication suggests a shift in the use of social platforms, with Facebook use decreasing among younger age groups, and TikTok and other apps becoming more prevalent. Digital technology for health is changing constantly, and this review captured a snapshot of an ever-evolving field. Technologies, their functions, and their potential are evolving so rapidly that more research is needed in this domain to keep pace.

As we performed a scoping review, we did not systematically assess the quality of the included studies. While all papers included in our analysis have been peer-reviewed, during the process of thematically analyzing the text, we noted high heterogeneity among papers, in terms of both methodological strength and content quality. Such variety among papers also reflect the various aims and research design used to investigate young people’s opinions. It is thus important to take this aspect into account when interpreting the findings, as we are aware that they cannot be generalized to the youth population as a whole.

Conclusion

This scoping review shows that research on young people's views on DHP is emerging, but is still scattered and not representative of the diversity of settings and countries. That said, young people, when asked, express opinions and make distinct recommendations for how to improve DHP. Therefore, we call for more thorough research concerning specific contexts and individual needs, as they play an important role in the use and acceptance of DHPs. Fine-grained research in this area will achieve a more comprehensive and reliable understanding of young people's opinions, thereby not only creating successful technology solutions, but also better informing health policies and responding to relevant concerns.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

References

Lupton D. Health promotion in the digital era: a critical commentary. Health Promot Int. 2015;30(1):174–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dau091.

Stark AL, Geukes C, Dockweiler C. Digital health promotion and prevention in settings: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(1):e21063. https://doi.org/10.2196/21063.

Steffens MS, Dunn AG, Leask J, Wiley KE. Using social media for vaccination promotion: practices and challenges. Digital Health. 2020;6:2055207620970785. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055207620970785.

Buhi ER, Klinkenberger N, Hughes S, Blunt HD, Rietmeijer C. Teens’ use of digital technologies and preferences for receiving STD prevention and sexual health promotion messages: implications for the next generation of intervention initiatives. 2013;40:52–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/olq.0b013e318264914a.

Lambert DN, Swartzendruber A. 271. Examining innovative digital methods for health promotion: the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of reaching sexually active adolescent substance users in the south through online social networking platforms. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66(2):S137.

WHO. The global action plan for healthy lives and well-being for all: strengthening collaboration among multilateral organizations to accelerate country progress on the health-related sustainable development goals: World Health Organization; 2019 [Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1262782/retrieve.

WHO. WHO guideline on self-care interventions for health and well-being: World Health Organization; 2021 [Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240052192.

UNICEF. The Changing Childhood Project. A multigenerational, international survey on 21st century childhood. 2021 [Available from: https://www.datocms-assets.com/30196/1637226180-changing-childhood-survey-report-2021.pdf.

Mwaura J, Carter V, Kubheka BZ. Social media health promotion in South Africa: opportunities and challenges. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2020;12(1):1–7.

Nwaozuru U, Obiezu-Umeh C, Shato T, Uzoaru F, Mason S, Carter V, et al. Mobile health interventions for HIV/STI prevention among youth in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs): a systematic review of studies reporting implementation outcomes. Implementation Science Communications. 2021;2(1):126. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00230-w.

Ferretti A, Vayena E, Blasimme A. Unlock Digital Health Promotion in LMICs to Benefit the Youth: SSRN; 2023 [Available from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4338613.

Richardson S, Lawrence K, Schoenthaler AM, Mann D. A framework for digital health equity. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2022;5(1):119. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-022-00663-0.

Tran Ngoc C, Bigirimana N, Muneene D, Bataringaya JE, Barango P, Eskandar H, et al., editors. Conclusions of the digital health hub of the Transform Africa Summit (2018): strong government leadership and public-private-partnerships are key prerequisites for sustainable scale up of digital health in Africa. BMC proceedings; 2018: BioMed Central. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12919-018-0156-3

Koh A, Swanepoel DW, Ling A, Ho BL, Tan SY, Lim J. Digital health promotion: promise and peril. Health Promot Int. 2021;36(Supplement_1):i70–80.

WHO. Young people and digital health interventions: working together to design better: World Health Organisation; 2020 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-10-2020-young-people-and-digital-health-interventions-working-together-to-design-better.

Youth 4 Health Futures. Governing health futures 2030: Growing up in a digital world. 2022 [Available from: https://www.governinghealthfutures2030.org/youth4healthfutures/ghfutures2030-youth-network/.

ITU. Digital technologies to achieve the UN SDGs 2021 [Available from: https://www.itu.int/en/mediacentre/backgrounders/Pages/icts-to-achieve-the-united-nations-sustainable-development-goals.aspx.

WHO. Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 [updated 2021. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/344249.

Governing Health Futures 2030 Commission. How digital technologies can support young people’s health along the age continuum: The Lancet & Financial Times Commission; 2021 [Available from: https://www.governinghealthfutures2030.org/pdf/policy-briefs/DigitalHealthAlongTheAgeContinuum.pdf.

Schwarz AF, Huertas-Delgado FJ, Cardon G, DeSmet A. Design features associated with user engagement in digital games for healthy lifestyle promotion in youth: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Games for Health Journal. 2020;9(3):150–63. https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2019.0058.

Shaw JM, Mitchell CA, Welch AJ, Williamson MJ. Social media used as a health intervention in adolescent health: a systematic review of the literature. Digital Health. 2015;1:2055207615588395.

Gilbey D, Morgan H, Lin A, Perry Y. Effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility of digital health interventions for LGBTIQ+ young people: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(12):e20158. https://doi.org/10.2196/20158.

Domhardt M, Engler S, Nowak H, Lutsch A, Baumel A, Baumeister H. Mechanisms of change in digital health interventions for mental disorders in youth: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(11):e29742. https://doi.org/10.2196/29742.

Kouvari M, Karipidou M, Tsiampalis T, Mamalaki E, Poulimeneas D, Bathrellou E, et al. Digital health interventions for weight management in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(2):e30675. https://doi.org/10.2196/30675.

Rose T, Barker M, Maria Jacob C, Morrison L, Lawrence W, Strömmer S, et al. A systematic review of digital interventions for improving the diet and physical activity behaviors of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(6):669–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.024.

Huang K-Y, Kumar M, Cheng S, Urcuyo AE, Macharia P. Applying technology to promote sexual and reproductive health and prevent gender based violence for adolescents in low and middle-income countries: digital health strategies synthesis from an umbrella review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1373. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08673-0.

Barry MM, Clarke AM, Jenkins R, Patel V. A systematic review of the effectiveness of mental health promotion interventions for young people in low and middle income countries. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):835. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-835.

Bouck Z, Straus SE, Tricco AC. Systematic Versus Rapid Versus Scoping ReviewsScoping reviews. In: Evangelou E, Veroniki AA, editors. Meta-Research: Methods and Protocols. Springer, US: New York, NY; 2022. p. 103–19.

UNDESA. Definition of youth 2013 [Available from: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/youth/fact-sheets/youth-definition.pdf.

WHO. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion: World Health Organisation; 1986 [Available from: https://intranet.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/129532/Ottawa_Charter.pdf.

WHO. Health promotion and disease prevention through population-based interventions, including action to address social determinants and health inequity 2023 [Available from: https://www.emro.who.int/about-who/public-health-functions/health-promotion-disease-prevention.html.

Kisling LA. M Das J. Prevention Strategies. StatPearls: StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

Tucker S. Welcome to the world of mHealth! Mhealth. 2015;1:1. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2306-9740.2015.02.01.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

Djuwitaningsih S, Setyowati. The Development of an Interactive Health Education Model Based on the Djuwita Application for Adolescent Girls. Compr Child Adolesc Nurs. 2017;40(sup1):169–82.DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/24694193.2017.1386986

Gibbs A, Gumede D, Luthuli M, Xulu Z, Washington L, Sikweyiya Y, et al. Opportunities for technologically driven dialogical health communication for participatory interventions: Perspectives from male peer navigators in rural South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292:114539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114539.

Gonsalves PP, Hodgson ES, Bhat B, Sharma R, Jambhale A, Michelson D, et al. App-based guided problem-solving intervention for adolescent mental health: a pilot cohort study in Indian schools. Evid Based Ment Health. 2021;24(1):11–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2020-300194.

Guerrero F, Lucar N, Garvich Claux M, Chiappe M, Perez-Lu J, Hindin MJ, et al. Developing an SMS text message intervention on sexual and reproductive health with adolescents and youth in Peru. Reprod Health. 2020;17(1):116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00943-6.

Haruna H, Hu X, Chu SKW, Mellecker RR, Gabriel G, Ndekao PS. Improving sexual health education programs for adolescent students through game-based learning and gamification. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(9):2027.

Januraga PP, Izwardi D, Crosita Y, Indrayathi PA, Kurniasari E, Sutrisna A, et al. Qualitative evaluation of a social media campaign to improve healthy food habits among urban adolescent females in Indonesia. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(S2):s98–107. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980020002992.

Aragão JMN, Gubert FDA, Torres RAM, Silva A, Vieira NFC. The use of facebook in health education: perceptions of adolescent students. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018;71(2):265–71. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0604.

Reynolds C, Sutherland MA, Palacios I. Exploring the use of technology for sexual health risk-reduction among ecuadorean adolescents. Ann Glob Health. 2019;85(1):57. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.35.

Zhang X, Xu X. Continuous use of fitness apps and shaping factors among college students: a mixed-method investigation. Int J Nurs Sci. 2020;7(Suppl 1):S80–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.07.009.

Giovenco D, Muessig KE, Horvitz C, Biello KB, Liu AY, Horvath KJ, et al. Adapting technology-based HIV prevention and care interventions for youth: lessons learned across five U.S. Adolescent Trials Network studies. Mhealth. 2021;7:21.

Rohde A, Duensing A, Dawczynski C, Godemann J, Lorkowski S, Brombach C. An app to improve eating habits of adolescents and young adults (Challenge to Go): systematic development of a theory-based and target group-adapted mobile app intervention. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(8):e11575. https://doi.org/10.2196/11575.

Byron P, Albury K, Evers C. “It would be weird to have that on Facebook”: young people’s use of social media and the risk of sharing sexual health information. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21(41):35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41686-5.

Heron KE, Romano KA, Braitman AL. Mobile technology use and mHealth text message preferences: an examination of gender, racial, and ethnic differences among emerging adult college students. Mhealth. 2019;5:2. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2019.01.01.

Gannon B, Davis R, Kuhns LM, Rodriguez RG, Garofalo R, Schnall R. A mobile sexual health app on empowerment, education, and prevention for young adult men (MyPEEPS Mobile): acceptability and usability evaluation. JMIR Form Res. 2020;4(4):e17901. https://doi.org/10.2196/17901.

Warnick JL, Pfammatter A, Champion K, Galluzzi T, Spring B. Perceptions of health behaviors and mobile health applications in an academically elite college population to inform a targeted health promotion program. Int J Behav Med. 2019;26(2):165–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-018-09767-y.

Simons D, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Clarys P, De Cocker K, Vandelanotte C, Deforche B. A smartphone app to promote an active lifestyle in lower-educated working young adults: development, usability, acceptability, and feasibility study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(2):e44. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.8287.

Gold J, Lim MS, Hellard ME, Hocking JS, Keogh L. What’s in a message? Delivering sexual health promotion to young people in Australia via text messaging. 2010;10:792.

Jones K, Williams J, Sipsma H, Patil C. Adolescent and emerging adults’ evaluation of a Facebook site providing sexual health education. Public Health Nurs. 2019;36(1):11–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12555.

Martin A, Caon M, Adorni F, Andreoni G, Ascolese A, Atkinson S, et al. A mobile phone intervention to improve obesity-related health behaviors of adolescents across Europe: Iterative Co-design and feasibility study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(3):e14118. https://doi.org/10.2196/14118.

Gewali A, Lopez A, Dachelet K, Healy E, Jean-Baptiste M, Harridan H, et al. A social media group cognitive behavioral therapy intervention to prevent depression in perinatal youth: stakeholder interviews and intervention design. JMIR Ment Health. 2021;8(9):e26188. https://doi.org/10.2196/26188.

Gold J, Lim MS, Hellard ME, Hocking JS, Keogh L. What’s in a message? delivering sexual health promotion to young people in Australia via text messaging. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:792. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-792.

Bottorff JL, Struik LL, Bissell LJ, Graham R, Stevens J, Richardson CG. A social media approach to inform youth about breast cancer and smoking: an exploratory descriptive study. Collegian. 2014;21(2):159–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2014.04.002.

Livingood WC, Monticalvo D, Bernhardt JM, Wells KT, Harris T, Kee K, et al. Engaging adolescents through participatory and qualitative research methods to develop a digital communication intervention to reduce adolescent obesity. Health Educ Behav. 2017;44(4):570–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198116677216.

Cheng VWS, Davenport TA, Johnson D, Vella K, Mitchell J, Hickie IB. An App that incorporates gamification, mini-games, and social connection to improve men’s mental health and well-being (MindMax): participatory design process. JMIR Ment Health. 2018;5(4):e11068. https://doi.org/10.2196/11068.

Farič N, Smith L, Hon A, Potts HWW, Newby K, Steptoe A, et al. A virtual reality exergame to engage adolescents in physical activity: mixed methods study describing the formative intervention development process. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e18161. https://doi.org/10.2196/18161.

Lattie E, Cohen KA, Winquist N, Mohr DC. Examining an app-based mental health self-care program, intellicare for college students: single-arm pilot study. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(10):e21075. https://doi.org/10.2196/21075.

Müssener U, Thomas K, Bendtsen P, Bendtsen M. High school students’ preferences and design recommendations for a mobile phone-based intervention to improve psychological well-being: mixed methods study. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2020;3(2):e17044. https://doi.org/10.2196/17044.

Watanabe-Ito M, Kishi E, Shimizu Y. Promoting healthy eating habits for college students through creating dietary diaries via a smartphone app and social media interaction: online survey study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(3):e17613. https://doi.org/10.2196/17613.

Honary M, Bell BT, Clinch S, Wild SE, McNaney R. Understanding the role of healthy eating and fitness mobile apps in the formation of maladaptive eating and exercise behaviors in young people. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(6):e14239. https://doi.org/10.2196/14239.

Frimming RE, Polsgrove MJ, Bower GG. Evaluation of a health and fitness social media experience. Am J Health Educ. 2011;42(4):222–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2011.10599191.

O’Reilly M, Dogra N, Hughes J, Reilly P, George R, Whiteman N. Potential of social media in promoting mental health in adolescents. Health Promot Int. 2019;34(5):981–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day056.

Wang Q, Egelandsdal B, Amdam GV, Almli VL, Oostindjer M. Diet and physical activity apps: perceived effectiveness by app users. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4(2):e33. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.5114.

Vornholt P, De Choudhury M. Understanding the role of social media-based mental health support among college students: survey and semistructured interviews. JMIR Ment Health. 2021;8(7):e24512. https://doi.org/10.2196/24512.

Tong HL, Coiera E, Laranjo L. Using a mobile social networking app to promote physical activity: a qualitative study of users’ perspectives. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(12):e11439. https://doi.org/10.2196/11439.

Kenny R, Dooley B, Fitzgerald A. Feasibility of “CopeSmart”: a telemental health app for adolescents. JMIR Ment Health. 2015;2(3):e22. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.4370.

Fleischmann RJ, Harrer M, Zarski AC, Baumeister H, Lehr D, Ebert DD. Patients’ experiences in a guided Internet- and App-based stress intervention for college students: a qualitative study. Internet Interv. 2018;12:130–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2017.12.001.

Atorkey P, Paul C, Wiggers J, Bonevski B, Mitchell A, Tzelepis F. Barriers and facilitators to the uptake of online and telephone services targeting health risk behaviours among vocational education students: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17):9336. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179336.

Crutzen R, Peters GJ, Portugal SD, Fisser EM, Grolleman JJ. An artificially intelligent chat agent that answers adolescents’ questions related to sex, drugs, and alcohol: an exploratory study. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(5):514–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.002.

Gkatzidou V, Hone K, Sutcliffe L, Gibbs J, Sadiq ST, Szczepura A, et al. User interface design for mobile-based sexual health interventions for young people: design recommendations from a qualitative study on an online Chlamydia clinical care pathway. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015;15:72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-015-0197-8.

Lupton D. Young people’s use of digital health technologies in the global north: narrative review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(1):e18286. https://doi.org/10.2196/18286.

Milward J, Deluca P, Drummond C, Kimergård A. Developing typologies of user engagement with the BRANCH alcohol-harm reduction smartphone app: qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(12):e11692. https://doi.org/10.2196/11692.

Crutzen R, de Nooijer J, Brouwer W, Oenema A, Brug J, de Vries NK. Internet-delivered interventions aimed at adolescents: a Delphi study on dissemination and exposure. 2008;23:427–39.

Miller T, Chandler L, Mouttapa M. A needs assessment, development, and formative evaluation of a health promotion smartphone application for college students. Am J Health Educ. 2015;46(4):207–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2015.1044138.

Williamson A, Barbarin A, Campbell B, Campbell T, Franzen S, Reischl TM, et al. Uptake of and engagement with an online sexual health intervention (HOPE eIntervention) among African American young adults: mixed methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(7):e22203. https://doi.org/10.2196/22203.

Gowin M, Cheney M, Gwin S, Franklin WT. Health and fitness app use in college students: a qualitative study. Am J Health Educ. 2015;46(4):223–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2015.1044140.

Burns JC, Arnault DS. Examining attitudes, norms, and perceived control: Young African American males’ views of social media as a mode for condom use education. Cogent Social Sciences. 2019;5(1):1588840. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1588840.

Gabrielli S, Rizzi S, Carbone S, Donisi V. A chatbot-based coaching intervention for adolescents to promote life skills: pilot study. JMIR Hum Factors. 2020;7(1):e16762. https://doi.org/10.2196/16762.

Depper A, Howe PD. Are we fit yet? English adolescent girls’ experiences of health and fitness apps. Health Sociol Rev. 2017;26(1):98–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2016.1196599.

Montagni I, Cariou T, Feuillet T, Langlois E, Tzourio C. Exploring digital health use and opinions of university students: field survey study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(3):e65. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.9131.

Goodyear VA, Armour KM, Wood H. Young people and their engagement with health-related social media: new perspectives. Sport Educ Soc. 2019;24(7):673–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2017.1423464.

Bohleber L, Crameri A, Eich-Stierli B, Telesko R, von Wyl A. Can we foster a culture of peer support and promote mental health in adolescence using a web-based app? a control group study. JMIR Ment Health. 2016;3(3):e45.

Lupton D. ‘Better understanding about what’s going on’: young Australians’ use of digital technologies for health and fitness. Sport Educ Soc. 2020;25(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2018.1555661.

Freeman B, Potente S, Rock V, McIver J. Social media campaigns that make a difference: what can public health learn from the corporate sector and other social change marketers? Public Health Res Pract. 2015;25(2):e2521517.

Vyas AN, Landry M, Schnider M, Rojas AM, Wood SF. Public health interventions: reaching Latino adolescents via short message service and social media. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(4):e99. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2178.

Acknowledgements

We thank Faustine Fuld for helping in the preliminary phases of this project.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich. This work was supported by Fondation Botnar [grant number OOG-20–024]. The funding body did not play any reole in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AF conceived and designed the study, AF and SH performed data extraction, analysis, drafted and edited the manuscript. EV critically revised subsequent versions of the manuscript for important intellectual content and is responsible for the overall content as guarantor. All authors critically read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study does not involve human participants and ethical approval was not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferretti, A., Hubbs, S. & Vayena, E. Global youth perspectives on digital health promotion: a scoping review. BMC Digit Health 1, 25 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s44247-023-00025-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s44247-023-00025-0