Abstract

The dramatic increase of different human activities around and along Ismailia Canal threats the groundwater system. The assessment of groundwater suitability for drinking purpose is needed for groundwater sustainability as a main second source for drinking. The Water Quality Index (WQI) is an approach to identify and assess the drinking groundwater quality suitability.

The analyses are based on Pearson correlation to build the relationship matrix between 20 variables (electrical conductivity (Ec), pH, total dissolved solids (TDS), sodium (Na), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), chloride (Cl), carbonate (CO3), sulphate (SO4), bicarbonate (HCO3), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), lead (Pb), cobalt (Co), chromium (Cr), cadmium (Cd), and aluminium (Al). Very strong correlation is found at [Ec with Na, SO4] and [Mg with Cl]; strong correlation is found at [TDS with Na, Cl], [Na with Cl, SO4], [K with SO4], [Mg with SO4] and [Cl with SO4], [Fe with Al], [Pb with Al]. The water type is Na–Cl in the southern area due to salinity of the Miocene aquifer and Mg–HCO3 water type in the northern area due to seepage from Ismailia Canal and excess of irrigation water.

The WQI classification for drinking water quality is assigned with excellent and good groundwater classes between km 10 to km 60, km 80 to km 95 and the adjacent areas around Ismailia Canal. While the rest of WQI classification for drinking water quality is assigned with poor, very poor, undesirable and unfit limits which are assigned between km 67 to km 73 and from km 95 to km 128 along Ismailia Canal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays, groundwater has become an important source of water in Egypt. Water crises and quality are serious concerns in a lot of countries, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions where water scarcity is widespread, and water quality assessment has received minimal attention [3, 9]. So, it is important to assess the quality of water to be used, especially for drinking purposes.

Poor hydrogeological conditions have been encountered causing adverse impacts on threatening the adjacent groundwater aquifer under the Ismailia Canal. The groundwater quality degradation is due to rapid urban development, industrialization, and unwise water use of agricultural water, either groundwater or surface water.

As groundwater quality is affected by several factors, an appropriate study of groundwater aquifers characteristics is an essential step to state a supportable utilization of groundwater resources for future development and requirements [11, 12]. It is important that hydrogeochemical information is obtained for the region to help improving the groundwater management practices (sustainability and protection from deterioration) [17].

Many researchers have paid great attention to groundwater studies. In the current study area, the hydrogeology and physio-hydrochemistry of groundwater in the current study area had been previously discussed by El Fayoumy [15] and classified the water to NaCl type; Khalil et al. [27] stated that water had high concentration of Na, Ca, Mg, and K. Geriesh et al. [21] detected and monitored a waterlogging problem at the Wadi El Tumilate basin, which increased salinity in the area. Singh [34] studied the problem of salinization on crop yield. Awad et al. [7] revealed that the groundwater salinity ranges between 303 ppm and 16,638 ppm, increasing northward in the area.

Various statistical concepts were used to understand the water quality parameters [24, 28, 35].

Armanuos et al. [4] studied the groundwater quality using WQI in the Western Nile Delta, Egypt. They had generated the spatial distribution map of different parameters of water quality. The results of the computed WQI showed that 45.37% and 66.66% of groundwater wells falls into good categories according to WHO and Egypt standards respectively.

Eltarabily et al. [19] investigate the hydrochemical characteristics of the groundwater at El-Khanka in the eastern Nile Delta to discuss the possibility of groundwater use for agricultural purposes. They used Pearson correlation to deduce the relationship between 13 chemical variables used in their analysis. They concluded that the groundwater is suitable for irrigation use in El-Qalubia Governorate.

The basic goal of WQI is to convert and integrate large numbers of complicated datasets of the physio-hydrochemistry elements with the hydrogeological parameters (which have sensitive effect on the groundwater system) into quantitative and qualitative water quality data, thus contributing to a better understanding and enhancing the evaluation of water quality [38]. The WQI is calculated by performing a series of computations to convert several values from physicochemical element data into a single value which reflects the water quality level's validity for drinking [16].

Based on the physicochemical properties of the groundwater, it should be appraised for various uses. One can determine whether groundwater is suitable for use or unsafe based on the maximum allowable concentration, which can be local or international. The type of the material surrounding the groundwater or dissolving from the aquifer matrix is usually reflected in the physicochemical parameters of the groundwater. These metrics are critical in determining groundwater quality and are regarded as a useful tool for determining groundwater chemistry and primary control mechanisms [18].

The objective of this research is to assess suitability of groundwater quality of the study area around Ismailia Canal for drinking purpose and generating WQI map to help decision-makers and local authorities to use the created WQI map for groundwater in order to avoid the contamination of groundwater and to facilitate in selection safely future development areas around Ismailia Canal.

Description of study area

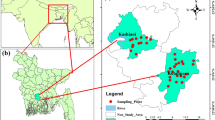

The study area lies between latitudes 30° 00′ and 31° 00′ North and longitude 31° 00′ and 32° 30′ East. It is bounded by the Nile River in the west, in the east there is the Suez Canal, in the south, there is the Cairo-Ismailia Desert road, and in the north, there are Sharqia and Ismailia Governorates as shown in Fig. 1. Ismailia Canal passes through the study area. It is considered as the main water resource for the whole Eastern Nile Delta and its fringes. Its intake is driven from the Nile River at Shoubra El Kheima, and its outlet at the Suez Canal. At the intake of the canal, there are large industrial areas, which include the activities of the north Cairo power plant, Amyeria drinking water plant, petroleum companies, Abu Zabaal fertilizer and chemical company, and Egyptian company of Alum. Ismailia Canal has many sources of pollution, which potentially affects and deteriorates the water quality of the canal [22].

The topography plays an important role in the direction of groundwater. The ground level in the study area is characterized by a small slope northern Ismailia Canal. It drops gently from around 18 m in the south close to El-Qanater El-Khairia to 2 amsl northward. While southern Ismailia Canal, it is characterized by moderate to high slope. The topography rises from 10 m to more than 200 m in the south direction.

Geology and hydrogeology

The sequence of deposits rocks of wells was investigated through the study of hydrogeological cross-section A-A′ and B-B′ located in Fig. 2a, b [32]. Section B-B′ shows that the study area represents two main aquifers that can be distinguished into the Oligocene aquifer (southern portion of the study area) and the Quaternary aquifer (northern portion of the study area). The Oligocene aquifer dominates the area of Cairo-Suez aquifer foothills. The Quaternary occupies the majority of the Eastern Nile Delta. It consists of Pleistocene sand and gravel. It is overlain by Holocene clay. The aquifer is semi-confined (old flood plain) and is phreatic at fringes areas in the southern portion of eastern Nile Delta fringes. The Quaternary aquifer thickness varies from 300 m (northern of the study area) to 0 at the boundary of the Miocene aquifer (south of the study area). The hydraulic conductivity ranges from 60 m/day to 100 m/day [8]. The transmissivity varies between 10,000 and 20,000 m2/day.

Groundwater recharge and discharge

The main source of recharge into the aquifer under the study area is the excess drainage surplus (0.5–1.1 mm/day) [29], in addition to the seepage from irrigation system including Damietta branch and Ismailia Canal.

Groundwater and its movements

In the current research, it was possible to attempt drawing sub-local contour maps for groundwater level with its movement as shown in Fig. 3. Figure 3 shows the main direction of groundwater flow from south to north. The groundwater levels vary between 5 m and 13 m (above mean sea level). The sensitive areas are affected by (1) the excess drainage surplus from the surface water reclaimed areas which located at low lying areas; (2) the seepage from the Ismailia Canal bed due to the interaction between it and the adjacent groundwater system, and (3) misuse of the irrigation water of the new communities and other issues. Accordingly, a secondary movement was established in a radial direction that is encountered as a source point at the low-lying area (Mullak, Shabab, and Manaief). Groundwater movement acts as a sink at lower groundwater areas (the northern areas of Ismailia Canal located between km 80 to km 90) due to the excessive groundwater extraction. The groundwater level reaches 2 m (AMSL). The groundwater levels range between + 15 m (AMSL) (southern portion of Ismailia Canal and study area near the boundary between the quaternary and Miocene aquifers).

Methods

The assessment of groundwater suitability for drinking purposes is needed and become imperative based on (1) the integration between the effective environmental hydrogeological factors (the selected 9 trace elements Fe, Mn, Zn, Cu, Pb, Co, Cr, Cd, Al) and 11 physio-chemical parameters (major elements of the anions and cations pH, EC, TDS, Na, K, Ca, Mg, Cl, CO3, SO4, HCO3); (2) evaluation of WQI for drinking water according to WHO [36] and drinking Egyptian standards limit [14]; (3) GIS is used as a very helpful tool for mapping the thematic maps to allocate the spatial distribution for some of hydrochemical parameters with reference standards.

The groundwater quality for drinking water suitability is assessed by collecting 53 water samples from an observation well network covering the area of study, as seen in Fig. 1. The samples were collected after 10 min of pumping and stored in properly washed 2 L of polyethylene bottles in iceboxes until the analyses were finished. The samples for trace elements were acidified with nitric acid to prevent the precipitation of trace elements. They were analyzed by the standard method in the Central Lab of Quality Monitoring according to American Public Health Association [2].

The water quality index is used as it provides a single number (a grade) that expresses overall water quality at a certain location based on several water quality parameters. It is calculated from different water parameters to evaluate the water quality in the area and its potential for drinking purposes [13, 25, 31, 33]. Horton [23] has first used the concept of WQI, which was further developed by many scholars.

The first step of the factor analysis is applying the correlation matrix to measure the degree of the relationship and strength between linearly chemical parameters, using “Pearson correlation matrix” through an excel sheet. The analyses are mainly based on the data from 53 wells for physio-chemical parameters for the major elements and trace elements. Accordingly, it classified the index of correlation into three classes: 95 to 99.9% (very strong correlation); 85 to 94.9% (strong correlation), 70 to 84.9% (moderately), < 70% (weak or negative).

Equation (1) [4] is used to calculate WQI for the effective 20 selected parameters of groundwater quality.

In which Qi is the ith quality rating and is given by equation (2) [4], Wi is the ith relative weight of the parameter i and is given by Eq. (3) [4].

Where Ci is the ith concentration of water quality parameter and Si is the ith drinking water quality standard according to the guidelines of WHO [36] and Egypt drinking water standards [14] in milligram per liter.

Where Wi is the relative weight, wi is the weight of ith parameter and n is the number of chemical parameters. The weight of each parameter was assigned (wi) according to their relative importance relevant to the water quality as shown in Table 2, which were figured out from the matrix correlation (Pearson correlation, Table 1). Accordingly, it was possible assigning the index for weight (wi). Max weight 5 was assigned to very strong effective parameter for EC, K, Na, Mg, and Cl; weight 4 was assigned to a strong effective parameter as TDS, SO4; 3 for a moderate effective parameter as Ca; and weight 2 was assigned to a weak effective parameter like pH, HCO3, CO3, Fe, Cr, Cu, Co, Cd, Pb, Zn, Mn, and Al. Equation (2) was calculated based on the concertation of the collected samples from representative 53 wells and guidelines of WHO [36] and Egypt drinking water standards [14] in milligram per liter. This led to calculation of the relative weight for the weight (Wi) by equation (3) of the selected 20 elements (see Table 2). Finally, Eq. (1) is the summation of WQI both the physio-chemical and environmental parameters for each well eventually.

The spatial analysis module GIS software was integrated to generate a map that includes information relating to water quality and its distribution over the study area.

Results and discussion

The basic statistics of groundwater chemistry and permissible limits WHO were presented in Table 3. It summarized the minimum, maximum, average, med. for all selected 20 parameters and well percentage relevant to the permissible limits for each one; the pH values of groundwater samples ranged from 7.1 to 8.5 with an average value of 7.78 which indicated that the groundwater was alkaline. While TDS ranged from 263 to 5765 mg/l with an average value of 1276 mg/l. Sodium represented the dominant cation in the analyzed groundwater samples as it varied between 31 and 1242 mg/l, with an average value of 270 mg/l. Moreover, sulfate was the most dominant anion which had a broad range (between 12 and 1108 mg/l), with an average value of 184 mg/l. This high sulfate concentration was due to the seepage from excess irrigation water and the dissolution processes of sulfate minerals of soil composition which are rich in the aquifer. Magnesium ranged between 11 and 243 mg/l, with an average value of 43 mg/l. The presence of magnesium normally increased the alkalinity of the soil and groundwater [10, 37]. Calcium ranged between 12 and 714 mg/l with a mean value of 119 mg/l. For all the collected groundwater samples, calcium concentration is higher than magnesium. This can be explained by the abundance of carbonate minerals that compose the water-bearing formations as well as ion exchange processes and the precipitation of calcite in the aquifer. Chloride content for groundwater samples varies between 18 and 2662 mg/l with an average value of 423 mg/l. Carbonate was not detected in groundwater, while bicarbonate ranged from 85 to 500 mg/l. Figures 5, 6, and 7 were drawn to show the extent of variation between the samples in each well.

Piper diagram [30] was used to identify the groundwater type in the study area as shown in Fig. 4. According to the prevailing cations and anions in groundwater samples Na–Cl water type in the southern area due to salinity of the Miocene aquifer, Mg–HCO3 water type in the northern area due to seepage from Ismailia Canal and excess of irrigation water and there is an interference zone which has a mixed water type between marine water from south and fresh water from north.

Atta, et al. [5] revealed that the abundance of Fe, Mn, and Zn in the groundwater is due to geogenic aspects, not pollution sources. Khalil et al. [26] and Awad et al. [6] revealed that the source of groundwater in the area is greatly affected by freshwater seepage from canals and excess irrigation water which all agreed with the study.

Table 3 and Fig. 8 showed that 100% of wells for EC were assigned at desirable limits. 43.79% of wells for TDS were assigned at the desirable limit and 27.05% of them at the undesirable limits. While pH, 81.25% were assigned at the desirable limit. The percentage of wells for the aerial distribution of cations concentration assigned at desirable limits ranged between 64.6% for K, 85.45% for Mg, 68.73% for Na, and 70.8% for Ca. While the percentage of wells for the aerial distribution of cations concentration assigned at the undesirable limits ranged between 8.3% for Mg, 31.27% for Na, 14.6% for K, and 16.7% for Ca.

The percentage of wells for the aerial distribution of anions concentration assigned at desirable limits ranged between 72.9% for Cl, 66.7% for HCO3, and 79.2% for SO4. While the percentage of wells for the aerial distribution of anions concentration assigned at the undesirable limit ranged between 4.2% for Cl, 0% for HCO3, and 20.8% for SO4 as shown in Table 3 and Fig. 8.

Table 3 and Fig. 8 presented the aerial distribution concentration for 8 sensitive trace elements. The percentage of wells assigned at desirable limits ranged between 100% for (Zn, Cr, and Co), 86% for Fe, 27.3% for Mn, 77.4% for Cd, 27.2% for Pb, and 96% for Al, while the percentage of wells assigned at undesirable limits ranged between 0% for (Fe, Zn, Cr, and Co), 50% for Mn, 13.6% for Cd, 36.4% for Pb, and 4% for Al.

Figure 8 summarizes the results of the concentration for the selected 20 elements (11 physio-hydrochemical characteristics, and 9 sensitive environmental trace elements) by %wells relevant to the limits of WHO for each element.

The water quality index is one of the most important methods to observe groundwater pollution (Alam and Pathak, 2010) [1] which agreed with the results. It was calculated by using the compared different standard limits of drinking water quality recommended by WHO (2008) and Egyptian Standards (2007). Two values for WQI were calculated and drawn according to these two standards. It was classified into six classes relevant to the drinking groundwater quality classes: excelled water (WQI < 25 mg/l), good water (25–50 mg/l), poor water (50–75 mg/l), very poor water (75–100 mg/l), undesirable water (100–150 mg/l), and unfit water for drinking water (> 150 mg/l) as shown in Fig. 9a, b. Figure 9a (WHO classification) indicated that in the most parts of the study area, the good water class was dominant and reached to 35.8%, 28.8% was excellent water; 7.5% were poor water, 11.3% very poor water quality, and 13.3% were unfit water for drinking water. Similarly, for Egyptian Standard classification via WQI, the study area was divided into six classes: Fig. 9b indicated that 35.8% of groundwater was categorized as excellent water quality, 34% as good water quality, 9.4% as poor water, 5.7% as very poor water, 1.9% as undesirable water and 13.3% as unfit water quality. This assessment was compared to Embaby et al. [20], who used WQI in the assessment of groundwater quality in El-Salhia Plain East Nile Delta. The study showed that 70% of the analyzed groundwater samples fall in the good class, and the remainder (30%), which were situated in the middle of the plain, was a poor class which mostly agreed with the study.

Conclusions and recommendation

This research studied the groundwater quality assessment for drinking using WQI and concluded that most of observation wells are located within desirable and max. allowable limits.

The groundwater in the study area is alkaline. TDS in groundwater ranged from 263 to 5765 mg/l, with a mean value of 1277 mg/l. Sodium and chloride are the main cation and anion constituents.

The water type is Na–Cl in the southern area due to salinity of the Miocene aquifer, Mg–HCO3 water type in the northern area due to seepage from Ismailia Canal and excess of irrigation water and there is an interference zone which has a mixed water type between marine water from south and fresh water from north.

The WQI relevant to WHO limits indicated that 23% of wells were located in excellent water quality class that could be used for drinking, irrigation and industrial uses, 38% of wells were located in good water quality class that could be used for domestic, irrigation, and industrial uses, 11% of wells were located in poor water quality class that could be used for irrigation and industrial uses, 8% of wells were located in very poor water quality class that could be used for irrigation, 6% of wells were located in unsuitable water quality class which is restricted for irrigation use and 15% of wells were located in unfit water quality which will require proper treatment before use.

The WQI relevant to Egyptian standard limits indicated that 25% of wells were located in excellent water quality class that could be used for drinking, irrigation, and industrial uses, 43% of wells were located in good water quality class that could be used for domestic, irrigation, and industrial uses, 8% of wells were located in poor water quality class that could be used for irrigation and industrial uses, 6% of wells were located in very poor water quality class that could be used in irrigation, 6% of wells were located in unsuitable water quality class which is restricted for irrigation use and 13% of wells were located in unfit water quality which will require proper treatment before use.

The percentage of wells located at unfit water for drinking were assigned in the Miocene aquifer, and north of Ismailia Canal between km 67 to km 73 and from km 95 to km 128.

It is highly recommended to study the water quality of the Ismailia Canal which may affect the groundwater quality. It is recommended to study the water quality in detail between km 67 to 73 and from km 95 to km 128 as the WQI is unfit in this region and needs more investigations in this region. A full environmental impact assessment should be applied for any future development projects to maximize and sustain the groundwater as a second resource under the area of Ismailia Canal.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they are part of a PhD thesis and not finished yet but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WQI:

-

Water Quality Index

- Ec:

-

Electrical conductivity

- TDS:

-

Total dissolved solids

- Na:

-

Sodium

- K:

-

Potassium

- Ca:

-

Calcium

- Mg:

-

Magnesium

- Cl:

-

Chloride

- CO3 :

-

Carbonate

- SO4 :

-

Sulphate

- HCO3 :

-

Bicarbonate

- Fe:

-

Iron

- Mn:

-

Manganese

- Zn:

-

Zinc

- Cu:

-

Copper

- Pb:

-

Lead

- Co:

-

Cobalt

- Cr:

-

Chromium

- Cd:

-

Cadmium

- Al:

-

Aluminium

References

Alam M, Pathak JK (2010) Rapid assessment of water quality index of Ramganga River, Western Uttar Pradesh (India) Using a computer programme. Nat Sci 8(11):1–8

American Public Health Association (2015) Standard methods for the examination of water sewage and industrial wastes, 23th edn. American Public Health Association, New York

Aragaw TT, Gnanachandrasamy G (2021) Evaluation of groundwater quality for drinking and irrigation purposes using GIS-based water quality index in urban area of Abaya-Chemo sub-basin of Great Rift Valley, Ethiopia. Appl Water Sci 11:148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-021-01482-6

Armanuos A, Negm A, Valeriano OC (2015) Groundwater quality investigation using water quality index and ARCGIS: case study: Western Nile Delta Aquifer, Egypt. Eighteenth International Water Technology Conference, IWTC18, pp 1–10

Atta SA, Afaf AO, Zamzam AH (2003) Hydrogeology and hydrochemistry of the groundwater at Khanka region, Egypt. International Symposium on Future Food Security for Africa, pp 136–155

Awad SR, El Fakharany ZM (2020) Mitigation of waterlogging problem in El-Salhiya area, Egypt. Water Sci J 34(1):1–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/11104929.2019.1709298

Awad SR, Atta SA, El Arabi N (2008) Hydrogeology and quality of groundwater in the Eastern Nile Delta region. Maadi Cultured Association. The fifth International Conference for Water

Awad SR (1999) Environmental studies on groundwater pollution in some localities in Egypt. Ph.D. Thesis. Faculty of Science, Cairo University

Batarseh M, Imreizeeq E, Tilev S, Al Alaween M, Suleiman W, Al Remeithi AM, Al Tamimi MK, Al Alawneh M (2021) Assessment of groundwater quality for irrigation in the arid regions using irrigation water quality index (IWQI) and GIS-Zoning maps: case study from Abu Dhabi Emirate, UAE. Groundwater Sustain Dev 14:100611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsd.2021.100611

Bousser MG, Amarenco P, Chamorro A et al (2011) Terutroban versus aspirin in patients with cerebral ischaemic events (PERFORM): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Lancet (London England) 377(9782):2013–2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60600-4

Carrera-Hernandez JJ, Gaskin SJ (2006) The groundwater-modeling tool for GRASS (GMTG): open source groundwater flow modelling. Comput Geosci 32(3):339–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2005.06.018

Chenini I, Ben MA (2010) Groundwater recharge study in arid region: an approach using GIS techniques and numerical modeling. Comput Geosci 36(6):801–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2009.06.014

Chourasia LP (2018) Assessment of ground-water quality using water quality index in and around Korba City, Chhattisgarh, India. Am J Software Eng Appl 7(1):15–21. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajsea.20180701.12

Egyptian Higher Committee for Water (2007) Egyptian standards for drinking water and domestic uses. EHCW, Cairo

El Fayoumy IF (1987) Geology of the Quaternary Succession and its Impact on the Groundwater Reservoir in the Nile Delta Region. Submitted to the Bull, Fac. of Sc., Monoufia Univ., Egypt, Egypt

El Osta M, Masoud M, Alqarawy A, Elsayed S, Gad M (2022) Groundwater suitability for drinking and irrigation using water quality indices and multivariate modeling in Makkah Al-Mukarramah Province, Saudi Arabia. Water 14(3):483. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14030483

El Osta M, Masoud M, Ezzeldin H (2020) Assessment of the geochemical evolution of groundwater quality near the El Kharga Oasis, Egypt using NETPATH and water quality indices. Environmental Earth Sciences 81:248. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-019-8793-z

El Osta M, Niyazi B, Masoud M (2022) Groundwater evolution and vulnerability in semi-arid regions using modeling and GIS tools for sustainable development: case study of Wadi Fatimah, Saudi Arabia. Environ Earth Sci 81:248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-022-10374-0

Eltarabily MG, Negm AM, Yoshimura C, Abdel-Fattah S, Saavedra OC (2018) Quality assessment of southeast Nile delta groundwater for irrigation. Water Resources 45(6):975–991. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0097807818060118

Embaby AA, Beheary MS, Rizk SM (2017) Groundwater quality assessment for drinking and irrigation purposes in El- Salhia Plain East Nile Delta Egypt. Int J Eng Technol Sci 12:51–73 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330105491_Groundwater_Quality_assessment_For_Drinking_And_Irrigation_Purposes_In_El-Salhia_Plain_East_Nile_Delta_Egypt

Geriesh MH, El-Rayes AE (2001) Municipal contamination of shallow groundwater beneath south Ismailia villages. Fifth international conference on geochemistry. Alexandria University, Egypt, pp 241–253

Geriesh MH, Balke K, El-Bayes A (2008) Problems of drinking water treatment along Ismailia canal province, Egypt. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 9(3):232–242. https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B0710634

Horton RK (1965) An index number system for rating water quality. J Water Pollut Control Fed 37(3):300–306

Isaaks EH, Srivastava RM (1989) An Introduction to Applied Geostatistics. Oxford University Press, New York

Kawo NS, Karuppannan S (2018) Groundwater quality assessment using water quality index and GIS technique in Modjo River Basin, central Ethiopia. J Afr Earth Sci 147:300–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2018.06.034

Khalil JB, Atta SA (1986) Hydrogeochemistry of groundwater in South of Ismailia canal, Egypt. Egypt J Geol 30(1-2):109–119

Khalil JB, Atta SA, Diab MS (1989) Hydrogeological Studies on the Groundwater Aquifer of the Eastern Part of the Nile Deltaic, Egypt, Water Science, 4th Issue, Egypt. Water Sci:79–90

Kumar D, Ahmed S (2003) Seasonal behaviour of spatial variability of groundwater level in a Granitic Aquifer in Monsoon Climate. Current Sci 84(2):188–196 https://www.jstor.org/stable/24108097

Morsy WS (2009) Environmental management of groundwater resources in the Nile Delta Regio, Ph.D. In: Thesis, Irrigation and Hydraulics Department, Faculty of Engineering, Cairo University, p 102

Piper AM (1944) A graphic representation in the geochemical interpretation of groundwater analyses. Transact Am Geophys Union, USA 25(6):914–928. https://doi.org/10.1029/TR025i006p00914

Rao GS, Nageswararao G (2013) Assessment of ground water quality using water quality index. Arch Environ Sci 7(1):1–5 https://aes.asia.edu.tw/Issues/AES2013/RaoGS2013.pdf

RIGW (1992) Hydrogeological Maps of Egypt, Scale 1: 100,000, Research Institute for Groundwater, National Water Research Center, Egypt.

Prerna S, Meher PK, Kumar A, Gautam P, Misha KP (2014) Changes in water quality index of Ganges river at different locations in Allahabad. Sustain Water Qual Ecol 3:67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.swaqe.2014.10.002

Singh A (2015) Soil salinization and waterlogging: a threat to environment and agricultural sustainability. Ecol Indicat 57(2015):128–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.04.027

Suk H, Lee K (1999) Characterization of a ground water hydrochemical system through multivariate analysis: clustering into groundwater zones. Ground Water 37(3):358–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6584.1999.tb01112.x

World Health Organization WHO. (2008) Guidelines for drinking water quality. 1st and 2nd Addenda, Geneva, Switzerland, 1(3).

Xu P, Feng W, Qian H, Zhang Q (2019) Hydrogeochemical characterization and irrigation quality assessment of shallow groundwater in the Central-Western Guanzhong Basin, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(9):1492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16091492

Yogendra K, Puttaiah ET (2008) Determination of water quality index and suitability of an urban waterbody in Shimoga Town, Karnataka. The Proceedings of Taal2007: The 12thWorld Lake Conference, Jaipur, India, pp 342–346

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank Research Institute for Groundwater that provided us with the necessary data during the study.

Funding

No funding has to be declared for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HS: investigation, methodology, writing—original draft. MA: investigation, writing—original draft and reviewing. AM: reviewing and editing. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Atta, H.S., Omar, M.AS. & Tawfik, A.M. Water quality index for assessment of drinking groundwater purpose case study: area surrounding Ismailia Canal, Egypt. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 69, 83 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-022-00138-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-022-00138-9