Abstract

Massive coastal bridges were damaged in Hurricanes Ivan (2004) and Katrina (2005), and considerable efforts have been devoted to the studies of wave forces acting on bridge decks since then. When the hurricane and tsunamis approach the coastal zones, the mean water level is elevated, making it possible for the incident wave to hit the bridge deck directly. The study of wave force acting on the bridge deck is essential for the investigation of bridge failure mechanism, and a literature review of wave forces with experimental and numerical methods after Hurricanes Ivan and Katrina is presented in this paper. Though the experiments and numerical models can not fully simulate the wave-deck interaction as in realistic conditions, remarkable progress has been achieved, and some significant findings help the researchers to further understand the failure mechanism of the bridge deck. Emphasis is given to the studies that have significantly improved our understanding of the topic. Challenges associated with the existing studies and suggestions for future studies are presented for a deeper understanding of the failure mechanism of the bridge deck, and more countermeasures are expected to protect the bridge deck under extreme wave forces.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Hurricanes Ivan (2004) and Katrina (2005) have caused $2.5 billion in damage to the coastal bridges in southeastern areas of the United States (Douglass et al. 2007), e.g., 103 bridge spans from the eastbound and westbound were entirely or partly removed from their initial positions on the support structures over Escambia Bay in Hurricane Ivan (2004), and more than 437 bridge spans were laterally displaced with varying distances in Hurricane Katrina (2005) (Sheppard and Marin 2009). Tsunamis also have caused extensive damage to the communities in coastal zones. A large number of bridges were washed away caused by the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami and 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami, leading to thousands of casualties as well (FHWA (Federal Highway Administration) 2008; Bricker and Nakayama 2014). This infers that the coastal bridge decks are weak when they are subjected to extreme wave loads induced by the hurricanes and tsunamis (Douglass et al. 2004; IEMURA et al. 2005; Ghobarah et al. 2006; Unjoh 2006; Mosqueda et al. 2007; Robertson et al. 2007a, 2007b; Kosa 2011; Kaufman et al. 2012; Stearns and Padgett 2012; Akiyama et al. 2013; Kawashima and Buckle 2013; McAllister 2014; Mas et al. 2015; Bueno 2017; Godart 2017). The mean water level is elevated as the hurricanes and tsunamis approach the coastal zones, making it possible for the incident wave to hit the bridge deck directly (Robertson et al. 2007a, 2007b; Chen et al. 2009; Webb and Cleary 2019). However, wave loads were not considered in the design of these bridges in the last century as the bridge deck elevations were thought to be out of the reach of extreme incident waves even during hurricanes and tsunamis.

Before the happening of massive damage of bridge decks in Hurricanes Ivan (2004) and Katrina (2005), much work had been done on wave forces on offshore platforms and decks (Kaplan et al. 1995; Suchithra and Koola 1995; Bea et al. 1999; Baarholm and Faltinsen 2004), open coast jetties (Overbeek and Klabbers 2001; Tirindelli et al., 2003; McConnell et al. 2003; Cuomo et al. 2003; Da Costa and Scott 1988; Sulisz et al. 2005), flat plates and docks (Wang 1970; Isaacson and Bhat 1996). Despite some similarities between these structures and coastal bridges, remarkable differences still exist, including the differences of local water depth, relative width of the bridge deck to wavelength, structure elevation from the still water level (SWL), entrapped air in the cavities, and so on. Motivated by the damage of bridge deck in Mississippi during Hurricane Camille, only two studies focused on the effects of vertical wave forces on bridge decks (Denson 1978, 1980), while some significant flaws existed in the studies (Douglass et al. 2006; Sheppard and Marin 2009). In general, the studies about the wave forces on bridge decks were scarce at that time. Since then, considerable efforts have been devoted to the studies of wave-deck interaction, indicating the event of massive bridge decks damaged in Hurricanes Ivan (2004) and Katrina (2005) is a turning point for the studies on wave forces. Experimental and numerical methods have been the two main approaches to study the wave forces on bridge decks.

A significant number of laboratory tests have been carried out to study the wave-deck interaction since the turning point (e.g., Douglass et al. 2006; IEMURA et al. 2007; Sugimoto and Unjoh 2007; Bradner 2008; McPherson 2008; Cuomo et al. 2009; Sheppard and Marin 2009; Bradner et al. 2011; Lau et al. 2011; Lukkunaprasit et al. 2011; Hayatdavoodi et al. 2014; Rahman et al. 2014; Seiffert et al. 2014; Seiffert et al. 2015; Hayatdavoodi et al. 2015; Guo et al. 2015a; Chen et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2018; Xiao and Guo 2018; Huang, Zhu, Cui, Duan, and Cai, 2018; Zhu et al. 2018; Huang, Duan, et al., 2019; Fang et al. 2019; Xiang et al. 2020; Zhu and Dong 2020). To gain a better understanding of the wave-deck interaction, Douglass et al. (2006) conducted experimental tests with a scale model (1:15) hit by normally incident waves under various water conditions, and some additional understandings of the magnitude of the forces that occurred for a set of wave conditions and given bridge geometry were provided. Fang et al. (2019) conducted a detailed test covering different wave angles in the wave flume, and the characteristics of wave forces under different wave conditions were studied, inferring the vertical wave force reached the peak at a wave angle of 30° under a clearance of 0.04 m. A lot of empirical formulas were later proposed for fast evaluation of wave forces on bridge decks based on the experimental results (e.g., Douglass et al. 2006; Cuomo et al. 2007; AASHTO, 2008; Chen et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2019; Xiang et al. 2020). Nevertheless, the majority of the empirical formula provides the maximum wave forces acting on the coastal bridge decks other than the instantaneous wave-deck interaction in each moment, which may bring errors in the final design of bridge decks.

In using a numerical method to analyze the problem of fluid-structure interaction, many researchers tend to use the potential flow theory with the assumptions of non-viscous and irrotational flow (e.g., Meng 2008; An and Faltinsen 2012; Ertekin et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2015; Hayatdavoodi and Ertekin 2015; Guo et al. 2015b). The governing equations are reduced to Laplace’s equation in the assumptions, and velocities can be obtained by velocity potential. Based on the potential theory, An and Faltinsen (2012) studied the linear free-surface effects on a horizontally submerged and perforated 2D thin plate in finite and infinite water depths, and the influences of the wavenumber, submergence, water depth, and perforation-effect KC-number were illustrated. Guo et al. (2015b) presented an analytical method to estimate the wave forces acting on a submerged bridge superstructure during a hurricane based on the potential flow approach, and the results were compared to test data from two hydrodynamic experiments, indicating the analytical model could be used effectively for the prediction of the maximum wave forces acting on a submerged bridge superstructure. However, the wave-deck interaction is highly nonlinear in many cases, especially when the bridge deck is located above the mean water level. When the incident wave directly hits the elevated bridge deck, wave breaking occurs, resulting in wave overtopping above the deck surface and air bubbles forming in the water. The conventional potential flow method faces a difficult challenge in accurately predicting the highly nonlinear wave-deck interaction, and such cases are best studied by the use of the computational fluid dynamics (CFD) solvers regardless of the submerged or elevated condition of the bridge deck (e.g., Huang and Xiao 2009; Bozorgnia et al. 2010; Xiao et al. 2010; Jin and Meng 2011; Bricker et al. 2012; Bozorgnia and Lee 2012; Yim and Azadbakht 2013; Azadbakht 2013; Azadbakht and Yim 2014; Hayatdavoodi et al. 2014; Xu and Cai 2014; Ataei and Padgett 2014; Seiffert et al. 2015; Xu and Cai 2015; Xu and Cai 2015; Chen et al. 2016; Xu et al. 2017; Xu et al. 2018a; Xu et al. 2018b; Xiao and Guo 2018; Huang, Yang, et al., 2019; Istrati and Buckle 2019; Qu et al. 2019; Moideen et al. 2019; Montoya et al. 2019; Greco et al. 2020; Hu et al. 2020; Qu et al. 2020a; Qu et al. 2020b; Xiang et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2020; Zhao et al. 2020a, 2020b; Zhu and Dong 2020).

In this literature review, the paper focus on the review of the studies about wave forces on the bridge decks by experimental and numerical methods after Hurricanes Ivan and Katrina. This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a literature review of the experiments conducted to investigate the wave-deck interaction. Section 3 presents a literature review of the CFD studies on the wave-deck interaction. Finally, Section 4 summarizes the findings with several conclusions.

2 Experimental method

Considerable experiments have been carried out to study the wave forces on coastal bridge decks since the turning point in 2004–2005, and part of these experiments are listed in Table 1 sorted by the publication date. The extreme incident waves hitting the bridge deck are usually induced by hurricanes or tsunamis, which is concluded that both hurricane-induced and tsunami-induced wave forces could cause damage to bridge decks (Xu and Cai 2014). In the coastal zones, the bridges are usually built over largely variable water depth ranges due to rapidly varying bathymetry, and the coastal bridge is a typical three-dimensional (3D) structure. Cuomo et al. (2009) designed a 3D experiment of wave-deck interaction to give a deep insight into spatial and temporal variability of wave loading along geometrically complex bridge decks, where the abutment, rail, diaphragm, pile, pile cap, and slopes of the bridge in the longitudinal and transversal directions were taken into account. Chen et al. (2018) studied the influence of abutment on the wave forces acting on the bridge deck by changing the contraction ratio, and found the effects of the contraction ratio on tsunami loads were different for horizontal force, vertical force, and overturning moment. A 3D complicated experimental setup can better reflect the wave-deck interaction in realistic conditions. However, most researchers in Table 1 tend to design a simplified 3D bridge deck model for saving the cost and better studying the influences of some essential parameters that played a critically important role in the wave-deck interaction.

2.1 Wave type

As for the wave type, most researchers tend to choose regular wave with single wave frequency and wave height (e.g., stokes wave, cnoidal wave, solitary wave) to simplify the experimental investigation. Nevertheless, the study of irregular wave considering the influence of the superposition of numerous waves with different frequencies and wave heights can better simulate the wave-deck interaction in realistic hydrodynamic conditions. Both regular and irregular waves were chosen as the incident wave in Bradner (2008), Bradner et al. (2008), and Bradner et al. (2011) for comparison, and the results indicated that the significant wave height and the average of the highest one-third of wave force exhibited a second-order polynomial relationship, which is similar to the cases of regular wave. Stokes wave and cnoidal wave are usually adopted to represent the hurricane-induced wave (e.g., Bradner et al. 2011; Seiffert et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2016; Huang, Zhu, Cui, Duan, and Cai, 2018). Zhu (1983) suggested using stokes wave theory at \( T\sqrt{g/d}\le 10 \), and cnoidal wave theory at \( T\sqrt{g/d}>10 \), where T is the incident wave period, g is the gravity acceleration and d is the local water depth. Besides, the solitary wave is most adopted to represent the tsunami-induced wave in the relative studies (e.g., Hayatdavoodi et al. 2014; Xiao and Guo, 2018; Huang, Duan, et al., 2019; Zhu and Dong 2020).

2.2 Motion of bridge deck

Table 1 shows that most experiments have treated the bridge decks as fixed without taking the influence of dynamic model responses into account. In the wave-deck interaction, the structural system is flexible and movable under the combined effects of the substructure stiffness and the interface stiffness between the substructure and superstructure shown in Fig. 1. The response of bridges mounted on piles can be modeled as a spring-mass-damper system with a single degree of freedom, where the flexibility of the prototype structure was experimentally modeled by a pair of elastic springs (Bradner 2008; Bradner et al. 2008; Bradner et al. 2011). Additionally, the bridge decks were entirely or partly removed from their initial positions by the field observation in Hurricanes Ivan and Katrina, indicating the bridge deck became unconstrained when the connection between superstructure and substructure became damaged. To model the unconstrained cases in realist conditions, researchers in Oregon State University carried out experiments to study the bridge decks which freely moved without spring constraint under incident wave forces (Bradner 2008; Bradner et al. 2008; Bradner et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2016). In the study of the comparison between rigid case (fixed deck) and soft case (movable deck constrained by spring), Bradner et al. (2011) found there was no significant difference in the positive peak vertical forces between these two cases, while some differences existed in the horizontal forces.

2.3 Model scale

It is shown in Table 1 that the scale of the model in the experiments ranges from 1:100 to 1:5. Numerous challenges are faced in the experimental modeling of wave-deck interaction, and the foremost is the kinematic similarity (Bradner et al. 2011). In a small-scale model, the diaphragms are usually eliminated for simplification, which may not yield realistic results. Besides, the effect of entrapped air may not be well studied under the same Froude number between the prototype and model (Cuomo et al. 2009), indicating a large-scale experiment is a good way to minimize the error brought by scale effects. Thus, researchers conducted a series of experiments with a large scale (1:5) reinforced concrete bridge superstructure in Oregon State University to study the wave-deck interaction for a better understanding of the wave forces on the damaged coastal highway bridges along the U.S. Gulf coast (Bradner 2008; Bradner et al. 2008; Bradner et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2016).

2.4 Force components

Laboratory measurements of wave forces acting on elevated bridge decks show that the typical time series of wave forces consist of two components, which are referred to here as an impact force and varying force as shown in Fig. 2 (McConnell et al. 2004; Douglass et al. 2007; Sheppard and Marin 2009; Bradner et al. 2011; Guo et al. 2015a, 2015b; Huang, Zhu, Cui, Duan, and Cai, 2018). The short-duration impact force occurs slightly before the peak of the slowly varying force. The impact force with high frequency is referred to as the slamming force, which is highly associated with the structure and incident wave. The slowly varying force is referred to as the quasi-static force, which changes magnitude and direction with the wave phase in the interaction. The quasi-static force is composed of three parts, i.e., the buoyancy force, the drag force, and the inertia force. The buoyancy force is equal to the fluid’s weight that the structure displaces, and the drag force consists of pressure drag and surface friction. The inertia force is associated with the momentum-driven force.

Field observations of post storms by Douglass et al. (2006) and Robertson et al. (2007a, 2007b) showed some bridge decks were submerged in the water, inferring the still water level (SWL) exceeded the bridge elevation. The time series of wave forces acting on partially/fully submerged bridge deck are different from the elevated cases, which is shown in Fig. 3 (Sheppard and Marin 2009). The slamming force decreases with the decrease of clearance between SWL and the bottom of the bridge girders. The peak of negative forces become generally larger when the clearance decreases. In addition, the buoyancy force increases when the bridge deck is submerged in the water, which may be destructive in these cases when the horizontal wave force is sufficiently large to overcome the friction between the superstructure and substructure. The elevation of the bridge deck varies in different places, which may be affected by many factors, such as geographical constraints, beautiful views, construction cost, and the guarantee of safe accessibility of ramp. A deep investigation of the wave forces acting on submerged and subaerial bridge decks helps to better understand the failure mechanism of bridge decks in various conditions.

Guo et al. (2015a, 2015b) analyzed the quasi-static and slamming components of hurricane-induced wave forces acting on a 1:10 scale T-type girder bridge specimen with different clearances, wave heights, and wave periods in the experiment. The findings showed that the wave force’s slamming component was relatively small compared with the maximum quasi-static force in the horizontal direction and the amplitude of the slamming force in the vertical direction was in the same order as the quasi-static force. The ratio of slamming force to maximum quasi-static force increased with the reduction of the bridge elevation until the clearance between the bottom of the girder and the SWL reached zero, and decreased to a small value when the bridge was submerged in the water. In the experimental study of wave forces on the Box girder deck, Huang, Zhu, Cui, Duan, and Cai (2018) found the wave force’s slamming component was not noticeable in the vertical direction and the total horizontal force could be taken as twice the quasi-static horizontal force. The geometrical difference of bridge deck shape between T-type and Box girder decks probably leads to the disparity of the role that slamming components played in horizontal and vertical wave forces. Xiang et al. (2020) conducted a large-scale experiment to study the tsunami-induced wave force on the elevated T-type girder bridge within various conditions. To get a comprehensive study of the force components, four ratios were defined for investigation, i.e., the ratio of the corresponding quasi-static force (at the instant of the maximum slamming force) to the maximum value of this force (Fqs_cor / Fqs_max), the ratio of the corresponding quasi-static value to the maximum of the slamming component (Fqs_cor / Fsl_max), the ratio of the maximum values of slamming component to the maximum quasi-static component (Fsl_max / Fqs_max), the summation of the maximum quasi-static and the maximum slamming components to the maximum of the measured total forces ((Fqs_max + Fsl_max) / Ftotal). Phase lags (time differences) between the maximum values of the slamming force and quasi-static force for the horizontal and vertical forces are listed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. The ratio values for the horizontal and vertical forces are also listed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. It is shown that the corresponding quasi-static force is between 46.4% and 100% of its maximum value in the horizontal direction, and between 26.9% and 95.8% of its maximum value in the vertical direction, indicating the happening of slamming force in the time series of total forces is correlated with wave height and force direction, which is also demonstrated by the differences of phase lag in two tables. It is interesting to see the slamming forces in both directions are in the same order as the maximum quasi-static forces (Fqs_max) and the corresponding quasi-static force (Fqs_cor), and the relationship of slamming force and quasi-static force is correlated with wave conditions. It is also noteworthy that the summation of the maximum quasi-static force and slamming force over-predicts the actual maximum force, and the over-prediction is among 10.2% to 38.9% for horizontal force and 1.7% to 42.9% for vertical force.

The maximum vertical force acting on the bridge deck tends to be larger than the maximum horizontal force (Bradner et al. 2011; Guo et al. 2015a, 2015b; Seiffert et al. 2015). Bradner et al. (2011) inferred the magnitude of the maximum vertical forces was approximately three to five times as large as that of the corresponding horizontal forces in the large-scale experiments. Seiffert et al. (2015) found the maximum vertical forces were roughly three times larger than horizontal forces in the experiments with a 1:35 scale bridge model. As for the phase lag between horizontal force and vertical force, Bradner et al. (2011) found no significant phase lag existed between these two forces on the fixed bridge deck. However, in the case of the movable bridge deck constrained by springs, a phase lag was found between the maximum horizontal and vertical forces, which was probably because the horizontal response was dominated by the fundamental mode of vibration of the bridge model.

2.5 Girder type

The girders of bridge deck damaged in Hurricanes Ivan and Katrina were all T-type, and most of the subsequent laboratory experiments focused on the T-type girder decks, which is extensively used in coastal zones of Eastern Pacific, especially in the coastal zones of North America. Nevertheless, Box girder bridge decks are most adopted in the design of bridge decks in Western Pacific, especially in China and Japan, as it has many merits compared with T-type girder decks. A number of bridges were washed away by the extreme tsunami wave caused by the 2011 earthquake off the Pacific coast of Tohoku, and Hayashi et al. (2013) conducted experiments to study the tsunami wave force acting on a Box girder bridge deck, and behaviors of tsunami wave attacking a scaled bridge model were also observed. Later, Huang, Zhu, Cui, Duan, and Cai (2018) and Huang, Duan, et al. (2019) carried out experiments to study hurricane-induced and tsunami-induced wave forces on coastal Box girder bridge decks, respectively, inferring the configurations of bridge deck played an important role in the wave-deck interaction.

To have a direct comparison of wave forces acting on T-type girder and Box girder decks, Huang, Duan, et al. (2019) utilized the CFD method to study the wave forces on the Box girder deck under different conditions, including four water depths and five wave heights for each bridge elevation, which was compared with the experimental data about the wave forces on the T-type girder decks in Hayatdavoodi et al. (2014). The maximum vertical force, minimum vertical force, maximum horizontal force, and minimum horizontal force in the time series of wave forces were chosen to study for comparison. As for the cases with elevated bridge deck, it was found that the positive horizontal force on the T-type girder deck was larger than that on the Box girder deck for most conditions. The reason to cause the force difference was that the wave hit directly on the web of the T-type girders, while the wave forces on the web of the Box girder were separated into two components (a horizontal component and a vertical component) due to the web angle of the box girder. The difference in the wave forces between two girder decks increased with the decrease of the elevation coefficient. With the increase of nondimensional wave height or the decrease of the elevation coefficient, the difference in the horizontal negative forces between T-type girder and box girder decks presented an increasing trend, which was possibly caused by the wave acting on the back of the web of girders. With the increase of the nondimensional wave height, the vertical uplift force on the deck with a box girder tended to increase. The difference in the vertical uplift forces between two types of girders with large elevation heights was significant. For example, the vertical force acting on the Box girder deck was 3 times larger than the vertical force acting on the T-type girder deck at a specified case. The difference was reduced when the incident wave height reduced and the bridge was at a higher elevation condition. Overall, Huang, Yang, et al., 2019concluded that the large vertical forces on a box girder deck could easily cause overturn damage to the deck, and a vertical restraint was more important than a lateral restraint in the design of a box girder deck compared with T-type girder deck.

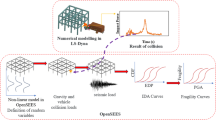

3 Numerical method

Based on experimental data, empirical equations have ever been proposed for the estimation of wave forces acting on the bridge deck. However, the empirical equations do not always provide accurate or acceptable results as mentioned above, especially when the deck width is comparable to the wavelength. To further investigate the wave-deck interaction, the numerical method has been adopted by many researchers. Though potential flow theory is able to give satisfactory results when the bridge deck is submerged, it faces many challenges in the elevated cases where wave broken happens. With the rapid development of the computer, the CFD method has gained popularity for it provides researchers with accurate instantaneous results regardless of submerged or elevated cases, and part of these studies are listed in Table 4 sorted by the publication date.

3.1 Governing equations

Riggs (2007) inferred wave forces attributable to hurricanes and tsunamis have similar requirements in the engineering design of bridge decks, and researchers choose either a hurricane-induced wave or tsunami-induced wave to be the incident wave in the CFD simulation as shown in Table 4. Both laminar model and turbulence model are adopted in the numerical method. Xu and Cai (2015) studied the positive peak horizontal and vertical forces acting on the T-type girder deck by both laminar and turbulence models, and found that the results by the laminar flow tended to be larger than those by the turbulent flow at most times, and the difference in the results between two models is within 10% for most cases. Xu et al. (2017) inferred the laminar model could make a good prediction in many specified cases, but unreliable results may be estimated in cases with high Reynolds number and wave breaking. Two turbulence models are mostly adopted in the simulation for the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations, i.e., k − ε model and the shear stress transport (SST) k − w model, which are both able to account for the turbulent fluctuations in the wave-deck interaction. Compared with k − ε model, SST k − w model can better resolve the computational domains with high Reynolds numbers in the main flow and relatively low Reynolds numbers in the near-wall domain. Compared with the Large Eddy Simulation (LES) model, the SST k − w model has less computational cost as LES requires more strictly for the grid mesh in the computational domain, especially for the near-wall mesh. To better capture the turbulent features for the bridge deck-wave interaction, a comprehensive comparison between different turbulence models is suggested to be carried out in future work.

3.2 2D and 3D numerical models

Similar to experimental studies, most researchers focus on the T-type girder deck, which is closely correlated with the shape of damaged bridge decks in Hurricanes Ivan and Katrina. To save the computational cost, the three-dimensional (3D) continuing bridge deck is often simplified to a two-dimensional (2D) computational domain without taking 3D bridge railings and diaphragms into consideration. Chen et al. (2016) utilized a 2D model to study the wave forces acting on a bridge deck, and the results were compared with the laboratory data obtained in the experiments carried out at Oregon State University (Bradner et al. 2008). The comparison showed the predicted forces agreed well with the experimental data except for the vertical force at small wave heights, where over-prediction was observed. In the 3D experiment, two narrow gaps existed between the bridge and the wave flume’s sidewalls, and part of the entrapped air in the cavities between the girders could escape from the side gaps when the wave hit the bridge, thus the vertical force was reduced. When the incident wave height was large, the water surface impacted on the entrapped air fiercely, and most of the entrapped air could not escape to the gap in time, which was similar to the 2D numerical case where no entrapped air could escape. When the incident wave height was small, a large portion of the entrapped air could escape to the gap in time as the water particle velocity contacted with the entrapped air was relatively small. The small difference between the 2D numerical model and the 3D experiment setup led to a slight error between simulated results and experimental data. Overall, it is a suitable option to choose a 2D model to simulate the wave-deck interaction, which has been demonstrated useful by many researchers listed in Table 4. To investigate the influences of rails, diaphragms and substructures on total wave forces, researchers are encouraged to use 3D numerical method (Azadbakht 2013).

3.3 Air entrapment

Air entrapment in the natural cavities created by the girders and diaphragms plays a significant role in the magnitude and duration of the wave-induced loads when a wave propagates past the structure (Sheppard and Marin, 2009; Hayatdavoodi and Cengiz Ertekin 2016), as shown in Fig. 4. The formation of air pocket induced by the air entrapment between the wave surface and bridge slab results in an increase of the displaced water volume, leading to a rise of buoyancy force on the body and a modification of the magnitude and duration of the impulse-like force. Air entrapment in the process of wave-deck interaction is classified into two types: one may happen when the wave crest hit a flat structure surface above the SWL, and the other appears when the wave surface exceeds the elevation of bridge girders, leading to the formation of air pockets in the entrapped zone between the girders (Hayatdavoodi and Cengiz Ertekin 2016). When the wave passes through the structure, the entrapped air acts somewhat like a spring in a spring-mass system, leading to a reduction of the magnitude of the slamming force and an increase of duration with smaller frequency. The frequency of the slamming force is determined by the girder spacing and the wave celerity. The number of slamming oscillations in the time series of vertical force is equal to the air cavity number (number of girders minus one) as shown in Fig. 5. To account for the effect of trapped air, a Trapped Air Factor (TAF) is calculated and applied to the quasi-steady vertical forces. The TAF is associated with bridge geometry, bridge elevation, and wave height. Based on the minimum and maximum TAF, it is convenient for the designers to use TAF to estimate a range of quasi-steady vertical forces (AASHTO 2008).

Time series of wave force on an elevated bridge deck with nine cavities (adapted from Sheppard and Marin 2009)

3.4 Motion of bridge deck

As shown in Table 4, the CFD method is applicable to simulate the motion response of bridge decks under wave forces (Ataei and Padgett 2014; Xu and Cai 2014, 2015; Xu and Cai 2015; Chen et al. 2016; Xu et al. 2017). When the bridge deck encounters an incident wave, both the substructure stiffness and the interface stiffness between the substructure and superstructure directly affect the motion displacement of the bridge deck. The substructure stiffness is determined by the soil condition, the structural stiffness of the piers/piles and so on. The interface stiffness depends on the connections between the superstructure and substructure, such as bearing types, shear keys, restraining cables, and shape memory alloys (Song et al. 2006; Dong et al. 2011; Xu and Cai 2015). To simulate the flexible structure, a numerical single degree of freedom system (SDOF) was proposed based on the mass-spring-damper system as shown in Fig. 6, where the bridge model could vibrate in the x/horizontal direction (Xu and Cai 2015; Xu et al. 2017). The motions of the bridge can be described as the following equations:

where X(t) is the instantaneous displacements of the bridge in the x-direction. m is the mass of the bridge. c and k are the structural damping and spring stiffness, respectively. F(t) is the total horizontal forces acting on the bridge, including the fluid forces and friction force. The friction force is neglected in the numerical system.

Azadbakht (2013) suggested the resistance of the bridges should also be investigated to provide information on how safe the current highway bridges were in an extreme wave. Generally speaking, F in Eq.(1) represents the net hydraulic wave forces acting on the bridge deck regardless of the motion state, and the net forces are mainly utilized to design the bridge deck. To calculate the forces transferred from the superstructure to the interface, the inertia forces should be included in the horizontal forces, i.e., \( F-m\ddot{X} \), which can be used to design the bearing supporting and the substructures. If the bridge deck is fixed, i.e., lateral restraining stiffness is infinite, the inertia force (\( m\ddot{X}\Big) \) is equal to zero, inferring no difference between wave force acting on the bridge deck and total force acting on the substructure. The influence of motion response on wave forces was illustrated in Fig. 7 (Left), showing the force response differed considerably in soft and rigid setups (Bradner et al. 2011). In the case of the soft setup, the force was significantly affected by the fundamental mode of vibration of the bridge model. Xu and Cai (2017) inferred the experimental horizontal force obtained in Bradner et al. (2011) included the inertial force, and simulated forces with and without considering inertia forces were studied for comparison. Figure 7 (Right) gives the simulated results of horizontal forces with and without considering inertia forces in a specified case, indicating the structural flexibilities in the transverse/lateral direction did not necessarily benefit the bridge structure with a noticeable force reduction (Xu and Cai 2017).

Left: Forces in soft and rigid setup (Adapted from Bradner et al. 2011); Right: Forces with and without considering inertia forces (Adapted from Xu and Cai 2017).

As many bridge decks were displaced varying distance on the pile under the wave action when the wave force surpassed the structure capacities, Chen et al. (2016) built a CFD model to study the wave forces acting on the unconstrained bridge deck, where both sway motion and heave motion were considered to better simulating the process of bridge deck washing away above the substructure.

3.5 Current

When the water surface is typically far below the elevation of the bridge girders, the joint effect of waves and currents is usually considered to design the coastal bridge (Huang, Zhu, Cui, Duan, and Zhang, 2018). Coastal bridges are exposed to hurricane-induced waves and storm surges during hurricanes, and ocean currents and waves coexist in the natural ocean environment. However, many researchers tend to only consider the wave force acting on the bridge deck in extreme conditions for model simplification, and the effect of current on total forces is unclear. As the action of currents leads to the changes in wave parameters and thus affects wave loads, considering wave-current interaction is a necessity for the study of water forces on coastal bridges. Chen et al. (2009) inferred it was a significant issue to propose a method to accurately estimate wave-current forces acting on coastal bridges under extreme condition, and more attentions were paid to the wave-current forces (e.g., Huang, Zhu, Cui, Duan, and Zhang, 2018; Qu et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2019). Zhang et al. (2019) investigated the wave-current loads on a Box girder bridge deck by experimental and numerical methods, and different parameters were taken into consideration, including wave heights, wave periods, current velocities, and submersion depths. The results indicated the maximum horizontal forces became larger and the maximum vertical forces became smaller in the following current, and vice versa for the reverse direction of opposing current with a low submergence depth. Nevertheless, the behaviors of wave forces became complicated in other situations, which was attributed to the change of wave parameter with the consideration of current.

3.6 Structural parameters

As discussed above, the wave-deck interaction is different between the T-type girder and Box girder decks. Other structural parameters also have a certain influence on the wave forces acting on the bridge deck, such as the geometric difference between flat plate and bridge model (McPherson 2008), girder spacing/number (Sheppard and Marin 2009), railing/parapet (Xu et al. 2017), deck inclination (Xu and Cai 2014; Bricker and Nakayama 2014), twin bridge decks (Xu et al. 2016; Xu, Cai, Han, et al., 2018; Xu, Chen, and Chen, 2018) and so on.

As the amount of entrapped air depends on the girder spacing/number, the girder spacing/number has a significant effect on the loading experienced by the structure. The girder spacing/number is important to both the slamming and quasi-static forces. Sheppard and Marin (2009) studied two cases with the same wave condition and structure parameter except for the girder spacing. The collected results showed the case with wider girder spacing (seven girders) trapped less air and consequently experienced a smaller quasi-static vertical force than the case with narrow girder spacing (four girders). The net effect of the entrapped air on slamming force is that the magnitude of the slamming is reduced and the duration is lengthened, and the number of slamming pulses is directly related to the number of entrapped air cavities. If the energy in the wave is sufficient, the number of slamming pulses is equal to the air cavities. Three slamming pulses were observed in the time series of collected force acting on the bridge structure with three cavities (four girders), while only five slamming pulses were observed for the case with six cavities (seven girders), which was attributed to the large energy dissipation when the wave propagated past the bridge deck with six cavities (Sheppard and Marin 2009). Bozorgnia and Lee (2012) utilized the CFD method to studied the accuracy of simulated results in capturing slamming pulses in the time series of wave force, indicating the accuracy was directly related to how accurately the air movement under the bridge superstructure was modeled. The simulated cases with a time step of Ti / 625 were found to accurately capture the slamming oscillations, while the cases with a time step of Ti / 125 were unable to give satisfactory predictions. Ti is the incident wave period.

Twin bridge decks are normally seen in coastal areas. In Hurricane Ivan (2004), 51 spans from the eastbound and 33 spans from the westbound were entirely or partly removed from their initial positions, indicating the decks in the eastbound and westbound suffered from different wave loads (Sheppard and Marin, 2009). Xu et al. (2016) investigated the characteristics of the solitary wave-induced forces on twin bridge decks with variable deck gaps in various conditions with different SWLs and submersion coefficients. The simulated results revealed that the wave forces on the seaward deck were larger than those on the landward deck for almost all cases with different deck gaps at a fixed bridge elevation. Xu, Chen, and Chen (2018) found the maximum uplift force on the seaward bridge deck appeared when the deck gap approached zero, half of the wavelength, one wavelength, or at a return interval of 0.5 wavelength. The maximum vertical loads were much larger than those for the horizontal loads, which suggested the vertical force on the seaward deck was easier affected by the landward deck than horizontal force.

3.7 Countermeasures

Compared with the experimental method, an advantage of the numerical method is that boundary condition and model geometry can be easily changed, thus the countermeasures on protecting the bridge deck are able to be tested in the numerical experiments. The most efficient way to prevent the coastal bridge from the extreme wave is to increase the elevation of the bridge deck. However, many coastal bridges can not be built at higher elevations from the SWL due to many restrictions, such as geographical constraints and beautiful views. Additionally, many old bridge decks were designed in a low elevation initially without considering the combined effect of the rising of mean water level and large wave forces in extreme conditions. Thus, it is essential to study the countermeasure to protect the coastal bridge decks. As shown in Table 4, the strategies for protecting the bridge deck including the studies of air vents in the bridge deck (e.g., Bozorgnia et al. 2010; Azadbakht 2013; Hayatdavoodi et al. 2014; Xu et al. 2016; Xiao and Guo 2018; Zhao et al. 2020a, 2020b), the height of shear keys (e.g., Chen et al. 2016), the connection between the superstructures and substructures (e.g., Xu and Cai 2015; Xu et al. 2017; Balomenos and Padgett 2018; Cai et al. 2018; Yuan et al. 2018), the offshore submerged breakwater (e.g., Wei and Dalrymple 2016), the offshore floating breakwater (e.g., Qu et al. 2020a) and so on. Figure 8 gives a design of air vent distributed on the slab and the corresponding airflow field induced by the incident wave. To change the interface stiffness, strategies may be learned from earthquake engineering, where base isolations, cable restraints, shear keys, and shape memory alloys are commonly used (Xu and Cai 2015). It is found that the increase of the structural flexibilities in the transverse/horizontal direction leads to larger horizontal forces on the interface between the superstructures and substructures, and rigidifying the superstructure is generally beneficial to reducing the hurricane-induced and tsunami-induced wave forces (Xu and Cai 2015; Xu and Cai 2017). To have a better practical performance evaluation and concept of interface design, Yuan et al. (2018) proposed a practical guide for the connection design under wave-deck interaction by suggesting using a structural capacity model with a three-step framework. With the further understanding of the failure mechanism of bridge deck under various wave conditions, more countermeasures and models about the quantification of vulnerability and resilience of the bridge system under extreme wave loadings are expected to be proposed for improving the resilience of the coastal bridges (Balomenos and Padgett 2018; Qeshta 2019; Qeshta et al. 2019; Zhao et al. 2020a, 2020b).

3.8 Expanded topics

As an alternative approach to traditional mesh-based methods, the mesh-free method of Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) has gained popularity for modeling free surface waves in coastal zones in the past decade, which is benefit from the property that SPH creates a free water surface directly since the particles represent the water and empty space represents the air (Dalrymple and Knio 2001; Gómez-Gesteira and Dalrymple 2004; Dalrymple and Rogers 2006; Capone et al. 2010; Farahani et al. 2013; Farahani and Dalrymple 2014; St-Germain et al. 2014; Shadloo et al. 2015; Wei et al. 2015; Wei and Dalrymple 2016; Liang et al. 2017; Sarfaraz and Pak 2017; Wen et al. 2018; Domínguez et al. 2019; Tripepi et al. 2020; Liu and Wang 2020). Wei and Dalrymple (2016) applied the SPH method to study the efficiency of tsunami mitigation by an up-wave service road bridge and an offshore breakwater. The simulated results not only showed the two-girder service road bridge function effectively in reducing tsunami wave forces on the rear bridges, but also indicated that a breakwater in the front of the bridge deck also helped to reduce the maximum tsunami wave forces to some extent correlated with the varying distance between the breakwater and the bridge. Sarfaraz and Pak (2017) utilized the mesh-free method (SPH) to investigate the process of tsunami-induced loads on bridge superstructures where different bridge elevation was considered (completely emerged, partially submerged, and completely submerged). The maximum forces and clockwise/counterclockwise moments induced at the center of the structure were determined, and the corresponding non-dimensional equations were proposed for fast estimation in engineering. SPH is a truly Lagrangian method where particles and their properties are simulated as they move in space with no requirement for any underlying mesh. This brings some key advantages over most mesh-based schemes, such as the extraordinary capability to simulate a large variety of complex flow, involving the complicated dynamic bridge deck motions in the water without any concern about mesh update in each time step.

Based on experimental and simulated data, Xu, Chen, Zhu, and Chakrabarti (2018) proposed a methodology for predicting solitary wave forces on bridge decks using artificial neural networks (ANNs), and the results indicated the ANN methodology was robust and capable of capturing the underlying physical complexity in the wave-deck interaction. Xu et al. (2020) presented a methodology for sequentially updating surrogate models with augmented data, which provided an effective approach to design experiments in civil engineering to maximize the information gain based on limited computational/experimental effort. It is demonstrated that it is an efficient way to use machine learning techniques to study the wave-deck interaction after sufficient experimental and simulated data are gained.

4 Conclusions

Field observations and researches have indicated that coastal bridges decks are vulnerable to extreme wave loads due to a storm or tsunami event. Hurricanes Ivan (2004) and Katrina (2005) is a turning point for the studies on wave forces. Since then, considerable efforts have been devoted to the studies of wave-deck interaction. In this paper, a literature review of wave forces on bridge decks with experimental and numerical methods after Hurricanes Ivan and Katrina is presented.

A number of experiments about the wave-deck interaction induced by hurricanes and tsunamis have been carried out since the turning point. Most researchers tend to choose the regular wave with a single wave frequency and wave height to simplify the experimental investigation, and some researchers take both regular and irregular waves into consideration for comparison. Stokes wave and cnoidal wave are the typical wave types regarded as the hurricane-induced wave, and the solitary wave is most adopted to represent the tsunami-induced wave. In the wave-deck interaction, the bridge deck is movable as the substructure stiffness and the interface stiffness are not infinite, and the bridge decks can be displaced varying distance on the pile under the wave action when the wave force surpasses the structure capacities. The bridge decks are usually regarded as fixed in the experiments, and the corresponding findings are limited. The study of movable bridge decks in the experiment is still scarce. The studies on the wave-deck interaction have been extended from T-type girder deck to Box girder deck, while a direct comparison between these two bridge types is scarce. The scale of the model in the experiments covers a wide range. As some structures are usually eliminated and the effect of entrapped air may not be well studied in small-scale experiments, a large scale experiment is expected. Wave forces acting on the elevated bridge decks consist of two components, i.e., slamming force and quasi-static force. The slamming force decreases with the decrease of clearance between SWL and the bottom of the bridge girders, and it becomes small in partially/fully submerged cases.

Potential flow theory is able to give satisfactory results in many cases, while it faces many challenges in the elevated cases where wave broken happens. CFD method has gained popularity for it provides the researchers with accurate instantaneous results regardless of submerged or elevated cases. Both laminar model and turbulence model have been adopted in the CFD method. Turbulence models are suggested in cases with high Reynolds number and wave breaking. The 2D model is mostly adopted in the numerical simulation as it saves the computational cost. However, over-prediction of the vertical force may happen in the 2D model as the escape of entrapped air in 3D experiments is not able to be simulated. Air entrapment affects not only the magnitude of wave force, but also the duration of the wave-induced loads. When the wave passes through the structure, the entrapped air acts somewhat like a spring in a spring-mass system, leading to a reduction of the magnitude of the slamming force and an increase of duration with smaller frequency. The frequency of the slamming force is determined by the girder spacing and the wave celerity. CFD method is applicable to simulate the motion response of bridge decks no matter whether it is restrained by the substructure. To simulate the flexible bridge deck, a numerical single degree of freedom system (SDOF) is found to perform well in the wave-deck interaction. Countermeasures to protect the bridge deck from wave damage have been studied by the CFD method. The strategies for protecting the bridge deck including the studies of air vents in the bridge deck, the height of shear keys, and the interface stiffness between the superstructures and substructures, and so on.

So far, significant progress has been achieved on determining wave loads on bridge decks within different conditions. Some following works are suggested to be carried out in the future to have a further understanding of the failure mechanism of the bridge deck and propose more countermeasures to protect the bridge deck under extreme wave loads.

-

1.

Currently, researchers tend to use regular waves instead of irregular waves to study wave-deck interaction. Though the adoption of the regular wave makes the operation easier, the wave-deck interaction in regular wave with single wave frequency and height does not fully reflect the realistic process of the interaction. Many essential findings within regular waves may not be applicable for the realistic cases in the irregular wave. As the influence of the superposition of numerous waves with different frequencies and wave heights on the wave-deck interaction is important, more numerical and laboratory experiments in irregular waves are expected to be carried out.

-

2.

To simulate the flexible structure under wave action, a single degree of freedom system (SDOF) was proposed based on the mass-spring-damper system. The SDOF system is applicable when the superstructure is connected to the substructure. However, when the wave force surpasses the structure capacities, the spring force becomes zero and the bridge deck is only constrained by frictional force. What is more, when the vertical wave force is large enough to overcome the bridge weight, the heave motion happens. Meanwhile, the pitch motion also occurs under the wave moment when the bridge is unconstrained in the directions of rotation. A multiple degrees of freedom system (MDOF) is expected to accurately simulate the motion of bridge deck when the connection between superstructure and substructure does not work.

-

3.

Coastal bridges are exposed to hurricane-induced waves, storm surges, and winds during hurricanes. Ocean currents and waves coexist in the natural ocean environment, and wave parameters are changed in the action of currents, leading to a change of wave loads on structures. The combined actions of wave and wind are also crucial for the wave-structure interaction as the free water surface can easily be deformed in a strong wind. The studies of wave-current and wave-wind interactions are both scarce in the current stage, and more efforts are suggested to be put on these topics. The study of the hydrodynamic characteristics of coastal bridges under the joint action of wave, wind, and current is also a necessity in the future, which can best reflect the realistic process of wave-deck interaction.

-

4.

To improve the resilience of the bridge deck, the influences of many countermeasures are expected to be further discussed. For example, the influence of air vents on the wave force has been well studied by 2D models, and 3D models are suggested to be utilized to study the optimum size and location of air vents for rapid air ventilation on the deck, such as the air vents on the slab and girder. Anchor cables are suggested to constrain the bridge deck, however, the tensile forces on the cables are not well studied and the efficiency of this solution is unknown. When the wave force surpasses the structure capacities, the bridge decks are displaced up and laterally displaced with varying distances on the pile cap. To avoid the failure of connection, it is highly suggested to introduce new approaches to increase the capacity of bridges.

-

5.

Lots of empirical formulas have been proposed for a fast evaluation of wave forces on bridge decks based on limited experimental and numerical results. These formulas are usually limited to specified wave conditions and structure parameters, and it is challenging to propose an empirical formula to account for various conditions. Machine learning technique is regarded to be an efficient way to study the wave-deck interaction. For example, deck configurations with overhang, railing, and air-venting holes would be worthy of studying using the machine learning technique. With sufficient experimental and simulated data, the machine learning technique can well predict the wave forces on the different geometrical bridge decks under various conditions.

Availability of data and materials

Some or all data, models, and code used during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Abbreviations

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural networks

- CFD:

-

Computational fluid dynamics

- LES:

-

Large eddy simulation

- MDOF:

-

Multiple degrees of freedom system

- RANS:

-

Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes

- SDOF:

-

Single degree of freedom system

- SPH:

-

Smoothed particle hydrodynamics

- SST:

-

Shear stress transport

- SWL:

-

Still water level

- TAF:

-

Trapped air factor

- 3D:

-

Three dimensional

- 2D:

-

Two dimensional

References

AASHTO (2008) Guide Specifications for Bridges Vulnerable to Coastal Storms. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, Washington D.C.

Akiyama M, Frangopol DM, Arai M, Koshimura S (2013) Reliability of bridges under tsunami hazards: emphasis on the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake. Earthq Spectra 29(S1):S295–S314

An S, Faltinsen OM (2012) Linear free-surface effects on a horizontally submerged and perforated 2D thin plate in finite and infinite water depths. Appl Ocean Res 37:220–234

Ataei N, Padgett JE (2014) Influential fluid–structure interaction modelling parameters on the response of bridges vulnerable to coastal storms. Struct Infrastruct Eng 11(3):321–33.

Azadbakht M (2013) Tsunami and hurricane wave loads on bridge superstructures

Azadbakht M, Yim SC (2014) Simulation and estimation of tsunami loads on bridge superstructures. J Waterw Port Coast Ocean Eng 141(2):04014031

Baarholm R, Faltinsen OM (2004) Wave impact underneath horizontal decks. J Mar Sci Technol 9(1):1–13

Balomenos GP, Padgett JE (2018) Fragility analysis of pile-supported wharves and piers exposed to storm surge and waves. J Waterw Port Coast Ocean Eng 144(2):04017046

Bea RG, Xu T, Stear J, Ramos R (1999) Wave forces on decks of offshore platforms. J Waterw Port Coast Ocean Eng 125(3):136–144

Bozorgnia M, Lee JJ (2012) Computational fluid dynamic analysis of highway bridge superstructures exposed to hurricane waves. Coast Eng Proc 1(33):70.

Bozorgnia M, Lee JJ, Raichlen F (2010) Wave structure interaction: role of entrapped air on wave impact and uplift forces. In: Proceedings of international conference on coastal engineering

Bradner C (2008) Large-scale laboratory observations of wave forces on a highway bridge superstructure. Master's thesis. Oregon State Univ, Portland.

Bradner C, Schumacher T, Cox D, Higgins C (2008) Large-scale wave flume experiments on highway bridge superstructures exposed to hurricane wave forces In Sixth National Seismic Conference on Bridges and Highways Multidisciplinary Center for Earthquake Engineering Research South Carolina Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration Transportation Research Board

Bradner C, Schumacher T, Cox D, Higgins C (2011) Experimental setup for a large-scale bridge superstructure model subjected to waves. J Waterw Port Coast Ocean Eng 137(1):3–11

Bricker JD, Kawashima K, Nakayama A (2012) CFD analysis of bridge deck failure due to tsunami. In: Proceedings of the international symposium on engineering lessons learned from the 2011 great East Japan earthquake, pp 1–4

Bricker JD, Nakayama A (2014) Contribution of trapped air, deck superelevation, and nearby structures to bridge deck failure during a tsunami. J Hydraul Eng 140(5):05014002

Bueno R (2017) Puerto Rico, climatic extremes, and the economics of resilience

Cai Y, Agrawal A, Qu K, Tang HS (2018) Numerical investigation of connection forces of a coastal bridge deck impacted by solitary waves. J Bridg Eng 23(1):04017108

Capone T, Panizzo A, Monaghan JJ (2010) SPH modelling of water waves generated by submarine landslides. J Hydraul Res 48(S1):80–84

Chen C, Melville BW, Nandasena NAK, Farvizi F (2018) An experimental investigation of tsunami bore impacts on a coastal bridge model with different contraction ratios. J Coast Res 34(2):460–469

Chen Q, Wang L, Zhao H (2009) Hydrodynamic investigation of coastal bridge collapse during hurricane Katrina. J Hydraul Eng 135(3):175–186

Chen XB, Zhan JM, Chen Q, Cox D (2016) Numerical modeling of wave forces on movable bridge decks. J Bridg Eng 21(9):04016055

Cuomo G, Allsop W, McConnell K (2003) Dynamic wave loads on coastal structures: analysis of impulsive and pulsating wave loads. In: Coastal structures 2003, pp 356–368

Cuomo G, Shimosako KI, Takahashi S (2009) Wave-in-deck loads on coastal bridges and the role of air. Coast Eng 56(8):793–809

Cuomo G, Tirindelli M, Allsop W (2007) Wave-in-deck loads on exposed jetties. Coast Eng 54(9):657–679

Da Costa SL, Scott JL (1988) Wave impact forces on the Jones Island east dock, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In Proc, Oceans 88(31):1231–1238

Dalrymple RA, Knio O (2001) SPH modelling of water waves. In: Coastal dynamics' 01, pp 779–787

Dalrymple RA, Rogers BD (2006) Numerical modeling of water waves with the SPH method. Coast Eng 53(2–3):141–147

Denson KH (1978) Wave forces on causeway-type coastal bridges. STIN 79:20293

Denson KH (1980) Wave forces on causeway-type coastal bridges: effects of angle of wave incidence and cross-section shape (no. MSHD-RD-80-070 final Rpt.)

Domínguez JM, Crespo AJ, Hall M, Altomare C, Wu M, Stratigaki V et al (2019) SPH simulation of floating structures with moorings. Coast Eng 153:103560

Dong J, Cai CS, Okeil AM (2011) Overview of potential and existing applications of shape memory alloys in bridges. J Bridg Eng 16(2):305–315

Douglass SL, Chen Q, Olsen JM, Edge BL, Brown D (2006) Wave forces on bridge decks. Coastal transportation engineering research and education center. Univ. of South Alabama, Mobile

Douglass SL, Hughes S, Rogers S, Chen Q (2004) The impact of hurricane Ivan on the coastal roads of Florida and Alabama: a preliminary report. Rep. To coastal transportation engineering research and education center, Univ. of South Alabama, Mobile

Douglass SL, McNeill LP, Edge B (2007) Wave loads on US highway bridges. In: Coastal structures: (in 2 volumes, pp 1659–1670

Ertekin RC, Hayatdavoodi M, Kim JW (2014) On some solitary and cnoidal wave diffraction solutions of the green–Naghdi equations. Appl Ocean Res 47:125–137

Fang Q, Hong R, Guo A, Li H (2019) Experimental investigation of wave forces on coastal bridge decks subjected to oblique wave attack. J Bridg Eng 24(4):04019011

Farahani RJ, Dalrymple RA (2014) Three-dimensional reversed horseshoe vortex structures under broken solitary waves. Coast Eng 91:261–279

Farahani RJ, Dalrymple RA, Hérault A, Bilotta G (2013) Three-dimensional SPH modeling of a bar/rip channel system. J Waterw Port Coast Ocean Eng 140(1):82–99

FHWA (Federal Highway Administration) (2008) Highways in the coastal environment

Ghobarah A, Saatcioglu M, Nistor I (2006) The impact of the 26 December 2004 earthquake and tsunami on structures and infrastructure. Eng Struct 28(2):312–326

Godart B (2017) New and on-going challenges for structural engineers regarding existing structures

Gómez-Gesteira M, Dalrymple RA (2004) Using a three-dimensional smoothed particle hydrodynamics method for wave impact on a tall structure. J Waterw Port Coast Ocean Eng 130(2):63–69

Greco F, Lonetti P, Blasi PN (2020) Vulnerability analysis of bridge superstructures under extreme fluid actions. J Fluids Struct 93:102843

Guo A, Fang Q, Bai X, Li H (2015a) Hydrodynamic experiment of the wave force acting on the superstructures of coastal bridges. J Bridg Eng 20(12):04015012

Guo A, Fang Q, Li H (2015b) Analytical solution of hurricane wave forces acting on submerged bridge decks. Ocean Eng 108:519–528

Hayashi H, Aoki K, Shijo R, Suzuki T (2013) Study on tsunami wave force acting on a bridge superstructure. Proceedings of the 29th US-Japan bridge engineering workshop, Tsukuba, pp 11–13

Hayatdavoodi M, Cengiz Ertekin R (2016) Review of wave loads on coastal bridge decks. Appl Mech Rev 68(3):030802.

Hayatdavoodi M, Ertekin RC (2015) Wave forces on a submerged horizontal plate-part I: theory and modelling. J Fluids Struct 54:566–579

Hayatdavoodi M, Seiffert B, Ertekin RC (2014) Experiments and computations of solitary-wave forces on a coastal-bridge deck. Part II: deck with girders. Coast Eng 88:210–228

Hayatdavoodi M, Seiffert B, Ertekin RC (2015) Experiments and calculations of cnoidal wave loads on a flat plate in shallow-water. J Ocean Eng Marine Energy 1(1):77–99

Hu Z, Zhang X, Li Y, Li X, Qin H (2020) Numerical study on hydroelastic interaction between solitary wave and submerged box. Ocean Eng 205:107299

Huang B, Duan L, Yang Z, Zhang J, Kang A, Zhu B (2019b) Tsunami forces on a coastal bridge deck with a box girder. J Bridg Eng 24(9):04019091

Huang B, Yang Z, Zhu B, Zhang J, Kang A, Pan L (2019a) Vulnerability assessment of coastal bridge superstructure with box girder under solitary wave forces through experimental study. Ocean Eng 189:106337

Huang B, Zhu B, Cui S, Duan L, Cai Z (2018a) Influence of current velocity on wave-current forces on coastal bridge decks with box girders. J Bridg Eng 23(12):04018092

Huang B, Zhu B, Cui S, Duan L, Zhang J (2018b) Experimental and numerical modelling of wave forces on coastal bridge superstructures with box girders, part I: regular waves. Ocean Eng 149:53–77

Huang W, Xiao H (2009) Numerical modeling of dynamic wave force acting on Escambia Bay bridge deck during hurricane Ivan. J Waterw Port Coast Ocean Eng 135(4):164–175

Iemura H, Pradono MH, Takahashi Y (2005) Report on the tsunami damage of bridges in Banda Aceh and some possible countermeasures. Environ Syst Res 28:214–214

Iemura H, Pradono MH, Yasuda T, Tada T (2007) Experiments of tsunami force acting on bridge models. In: Proceedings of the JSCE earthquake engineering symposium. Japan Society of Civil Engineers, 29:902–11.

Isaacson M, Bhat S (1996) Wave forces on a horizontal plate. Int J Offshore Polar Eng 6(01):19-26.

Istrati D, Buckle I (2019) Role of trapped air on the tsunami-induced transient loads and response of coastal bridges. Geosciences 9(4):191

Jin J, Meng B (2011) Computation of wave loads on the superstructures of coastal highway bridges. Ocean Eng 38(17–18):2185–2200

Kaplan P, Murray JJ, Yu WC (1995) Theoretical analysis of wave impact forces on platform deck structures (no. CONF-950695-). American Society of Mechanical Engineers, New York

Kaufman SM, Qing C, Levenson N, Hanson M (2012) Transportation during and after hurricane Sandy

Kawashima K, Buckle I (2013) Structural performance of bridges in the Tohoku-oki earthquake. Earthq Spectra 29(S1):S315–S338

Kosa K (2011) Damage analysis of bridges affected by tsunami due to great East Japan earthquake. In: Proceedings of the international symposium on engineering lessons learned from the, pp 1–4

Lau TL, Ohmachi T, Inoue S, Lukkunaprasit P (2011) Experimental and numerical modeling of tsunami force on bridge decks (pp. 105–130). InTech, Rijeka

Liang D, Jian W, Shao S, Chen R, Yang K (2017) Incompressible SPH simulation of solitary wave interaction with movable seawalls. J Fluids Struct 69:72–88

Liu Q, Sun T, Wang D, Wei Z (2019) Wave uplift force on horizontal panels: a laboratory study. J Oceanol Limnol 37(6):1899–1911

Liu Z, Wang Y (2020) Numerical investigations and optimizations of typical submerged box-type floating breakwaters using SPH. Ocean Eng 209:107475

Lukkunaprasit P, Lau TL, Ruangrassamee A, Ohmachi T (2011) Tsunami wave loading on a bridge deck with perforations. Sci Tsunami Haz 30(4):244-52.

Mas E, Bricker J, Kure S, Adriano B, Yi C, Suppasri A, Koshimura S (2015) Field survey report and satellite image interpretation of the 2013 super typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 15(4):805-16.

McAllister T (2014) The performance of essential facilities in Superstorm Sandy. In: Structures congress 2014, pp 2269–2281

McConnell K, Allsop W, Allsop NWH, Cruickshank I (2004) Piers, jetties and related structures exposed to waves: guidelines for hydraulic loadings Thomas Telford

McConnell KJ, Allsop NWH, Cuomo G, Cruickshank IC (2003) New guidance for wave forces on jetties in exposed locations. Paper to Conf. COPEDEC VI, Colombo, p 20

McPherson RL (2008) Hurricane induced wave and surge forces on bridge decks. Master's thesis. Texas A&M University.

Meng B (2008) Calculation of extreme wave loads on coastal highway bridges (Vol. 70, no. 02)

Moideen R, Ranjan Behera M, Kamath A, Bihs H (2019) Effect of girder spacing and depth on the solitary wave impact on coastal bridge deck for different airgaps. J Marine Sci Eng 7(5):140

Montoya A, Matamoros A, Testik F, Nasouri R, Shahriar A, Majlesi A (2019) Structural vulnerability of coastal bridges under extreme hurricane conditions

Mosqueda G, Porter KA, O'Connor J, McAnany P (2007) Damage to engineered buildings and bridges in the wake of hurricane Katrina. In: Forensic engineering (2007), pp 1–11

Overbeek J, Klabbers IM (2001) Design of jetty decks for extreme vertical wave loads. In: Ports' 01: America's ports: gateway to the global economy, pp 1–10

Qeshta I (2019) Fragility and resilience of bridges subjected to extreme wave-induced forces

Qeshta IM, Hashemi MJ, Gravina R, Setunge S (2019) Review of resilience assessment of coastal bridges to extreme wave-induced loads. Eng Struct 185:332–352

Qu K, Sun WY, Kraatz S, Deng B, Jiang CB (2020a) Effects of floating breakwater on hydrodynamic load of low-lying bridge deck under impact of cnoidal wave. Ocean Eng 203:107217

Qu K, Sun WY, Tang HS, Jiang CB, Deng B, Chen J (2019) Numerical study on hydrodynamic load of real-world tsunami wave at highway bridge deck using a coupled modeling system. Ocean Eng 192:106486

Qu K, Tang HS, Agrawal A, Cai Y, Jiang CB (2018) Numerical investigation of hydrodynamic load on bridge deck under joint action of solitary wave and current. Appl Ocean Res 75:100–116

Qu K, Wen BH, Ren XY, Kraatz S, Sun WY, Deng B, Jiang CB (2020b) Numerical investigation on hydrodynamic load of coastal bridge deck under joint action of solitary wave and wind. Ocean Eng 217:108037

Rahman S, Akib S, Shirazi SM (2014) Experimental investigation on the stability of bride girder against tsunami forces. SCIENCE CHINA Technol Sci 57(10):2028–2036

Riggs HR (2007) JWPCOE special issue: tsunami engineering (introduction). J Waterw Port Coast Ocean Eng 133(6):381–381

Robertson IN, Riggs HR, Yim SC, Young YL (2007a) Lessons from hurricane Katrina storm surge on bridges and buildings. J Waterw Port Coast Ocean Eng 133(6):463–483

Robertson IN, Yim S, Riggs HR, Young YL (2007b) Coastal bridge performance during hurricane Katrina. In: Third international conference on structural engineering, mechanics and computation, SEMC-2007, Cape Town, South Africa, Millpress, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, pp 1864–1870

Sarfaraz M, Pak A (2017) SPH numerical simulation of tsunami wave forces impinged on bridge superstructures. Coast Eng 121:145–157

Seiffert B, Hayatdavoodi M, Ertekin RC (2014) Experiments and computations of solitary-wave forces on a coastal-bridge deck. Part I: flat plate. Coast Eng 88:194–209

Seiffert BR, Hayatdavoodi M, Ertekin RC (2015) Experiments and calculations of cnoidal wave loads on a coastal-bridge deck with girders. Eur J Mechan-B/Fluids 52:191–205

Shadloo MS, Weiss R, Yildiz M, Dalrymple RA (2015) Numerical simulation of long wave runup for breaking and nonbreaking waves. Int J Offshore Polar Eng 25(01):1–7

Sheppard DM, Marin J (2009) Wave loading on bridge decks: final report

Song G, Ma N, Li HN (2006) Applications of shape memory alloys in civil structures. Eng Struct 28(9):1266–1274

Stearns M, Padgett JE (2012) Impact of 2008 hurricane Ike on bridge infrastructure in the Houston/Galveston region. J Perform Constr Facil 26(4):441–452

St-Germain P, Nistor I, Townsend R, Shibayama T (2014) Smoothed-particle hydrodynamics numerical modeling of structures impacted by tsunami bores. J Waterw Port Coast Ocean Eng 140(1):66–81

Suchithra N, Koola PM (1995) A study of wave impact of horizontal slabs. Ocean Eng 22(7):687–697

Sugimoto T, Unjoh S (2007) Hydraulic model tests on the bridge structures damaged by tsunami and tidal wave. In: Proc., 23th US–Japan bridge engineering workshop. Public Works Research Institute, Tsukuba, pp 1–10

Sulisz W, Wilde P, Wisniewski M (2005) Wave impact on elastically supported horizontal deck. J Fluids Struct 21(3):305–319

Tirindelli M, Cuomo G, Allsop W, McConnell K (2003) Exposed jetties: inconsistencies and gaps in design methods for wave-induced forces. In: Coastal engineering 2002: solving coastal conundrums, pp 1684–1696

Tripepi G, Aristodemo F, Meringolo DD, Gurnari L, Filianoti P (2020) Hydrodynamic forces induced by a solitary wave interacting with a submerged square barrier: physical tests and δ-LES-SPH simulations. Coast Eng 158:103690

Unjoh S (2006) Damage investigation of bridges affected by tsunami during 2004 North Sumatra earthquake, Indonesia. In: Fourth international workshop on seismic design and retrofit of transportation FacilitiesMultidisciplinary Center for Earthquake Engineering ResearchFederal highway administration

Wang H (1970) Water wave pressure on horizontal plate. J Hydraul Div 96(10):1997–2017

Webb BM, Cleary JC (2019) Drag-induced displacement of a simply supported bridge span during hurricane Katrina. J Perform Constr Facil 33(4):04019040

Wei Z, Dalrymple RA (2016) Numerical study on mitigating tsunami force on bridges by an SPH model. J Ocean Eng Marine Energy 2(3):365–380

Wei Z, Dalrymple RA, Hérault A, Bilotta G, Rustico E, Yeh H (2015) SPH modeling of dynamic impact of tsunami bore on bridge piers. Coast Eng 104:26–42

Wen H, Ren B, Wang G (2018) 3D SPH porous flow model for wave interaction with permeable structures. Appl Ocean Res 75:223–233

Xiang T, Istrati D, Yim SC, Buckle IG, Lomonaco P (2020) Tsunami loads on a representative coastal bridge deck: experimental study and validation of design equations. J Waterw Port Coast Ocean Eng 146(5):04020022

Xiao H, Huang W, Chen Q (2010) Effects of submersion depth on wave uplift force acting on Biloxi Bay bridge decks during hurricane Katrina. Comput Fluids 39(8):1390–1400

Xiao SC, Guo AX (2018) Effects of air relief openings on the mitigation of solitary wave forces on bridge decks. J Hydrodyn 31(3):594–602

Xu G, Cai C, Deng L (2017) Numerical prediction of solitary wave forces on a typical coastal bridge deck with girders. Struct Infrastruct Eng 13(2):254–272

Xu G, Cai CS (2014) Wave forces on Biloxi Bay bridge decks with inclinations under solitary waves. J Perform Constr Facil 29(6):04014150

Xu G, Cai CS (2015) Numerical simulations of lateral restraining stiffness effect on bridge deck–wave interaction under solitary waves. Eng Struct 101:337–351

Xu G, Cai CS (2017) Numerical investigation of the lateral restraining stiffness effect on the bridge deck-wave interaction under stokes waves. Eng Struct 130:112–123

Xu G, Cai CS, Han Y (2016) Investigating the characteristics of the solitary wave-induced forces on coastal twin bridge decks. J Perform Constr Facil 30(4):04015076

Xu G, Cai CS, Han Y, Wu C, Xue F (2018a) Numerical assessment of the wave loads on coastal twin bridge decks under stokes waves. J Coast Res 34(3):628–639

Xu G, Chen Q, Chen J (2018b) Prediction of solitary wave forces on coastal bridge decks using artificial neural networks. J Bridg Eng 23(5):04018023

Xu G, Chen Q, Zhu L, Chakrabarti A (2018c) Characteristics of the wave loads on coastal low-lying twin-deck bridges. J Perform Constr Facil 32(1):04017132

Xu G, Kareem A, Shen L (2020) Surrogate modeling with sequential updating: applications to bridge deck–wave and bridge deck–wind interactions. J Comput Civ Eng 34(4):04020023

Yang W, Lai W, Zhu Q, Zhang C, Li F (2020) Study on generation mechanism of vertical force peak values on T-girder attacked by tsunami bore. Ocean Eng 196:106782

Yim SC, Azadbakht M (2013) Tsunami forces on selected California coastal bridges (no. CA13-1983)

Yuan P, Xu G, Chen Q, Cai CS (2018) Framework of practical performance evaluation and concept of interface design for bridge deck–wave interaction. J Bridg Eng 23(7):04018048

Zhang J, Zhu B, Kang A, Yin R, Li X, Huang B (2019) Experimental and numerical investigation of wave-current forces on coastal bridge superstructures with box girders. Adv Struct Eng 23(7):1438–1453

Zhao BB, Duan WY, Ertekin RC (2014) Application of higher-level GN theory to some wave transformation problems. Coast Eng 83:177–189

Zhao BB, Duan WY, Ertekin RC, Hayatdavoodi M (2015) High-level green–Naghdi wave models for nonlinear wave transformation in three dimensions. J Ocean Eng Marine Energy 1(2):121–132

Zhao E, Sun J, Tang Y, Mu L, Jiang H (2020a) Numerical investigation of tsunami wave impacts on different coastal bridge decks using immersed boundary method. Ocean Eng 201:107132

Zhao R, Yuan Y, Wei X, Shen R, Zheng K, Qian Y et al (2020b) Review of annual progress of bridge engineering in 2019. Adv Bridge Eng 1(1):1–57

Zhu D, Dong Y (2020) Experimental and 3D numerical investigation of solitary wave forces on coastal bridges. Ocean Eng 209:107499

Zhu M, Elkhetali I, Scott MH (2018) Validation of OpenSees for tsunami loading on bridge superstructures. J Bridg Eng 23(4):04018015

Zhu YR (1983) Analyses of the ranges of validity for several wave theories. Coast Eng 2:13–29

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for providing constructive comments.

Funding

This research was jointly supported by department of Education of Guangdong Province, China (2019KQNCX047, KA200190148), department of Natural Resources of Guangdong Province, China ([2020]017), State Key Laboratory of Tropical Oceanography, South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (LTO2008), and Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52078425). All the opinions presented here are those of the writers, not necessarily representing those of the sponsors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, XC and GX; Formal analysis, XC; Investigation, XC; Supervision, GX, ZC, XZ and QD; Writing—original draft, XC; Writing—review & editing, GX. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Chen, Z., Xu, G. et al. Review of wave forces on bridge decks with experimental and numerical methods. ABEN 2, 1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43251-020-00022-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43251-020-00022-7