Abstract

Background

The duration of immunological persistence in COVID-19-vaccinated individuals is considered a matter of concern. Some studies have shown that anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies degrade rapidly. Due to diminishing immunity after vaccination, some people may catch an infection again after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine.

Objectives

The purpose of the present study was to measure the COVID-19 post-vaccination infection reported by the vaccinated participants and to identify possible associated risk factors among hospital attendants in Qena city.

Material and method

A cross-sectional study was carried out on 285 participants who received COVID-19 vaccines and were aged 18 years or more. A structured questionnaire was used as a tool for data collection.

Results

13.7% of the vaccinated participants reported catching the COVID-19 infection after vaccination. Healthcare workers were more susceptible to the COVID-19 infection after vaccination than non-healthcare workers. Post-vaccination infection among participants who received Viral vector vaccines, Inactivated vaccines, and mRNA vaccines were 16.7%, 15.7%, and 3.6%, respectively.

Conclusion

Healthcare professionals need to take strict preventive measures since, even after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, they are more vulnerable to infection than non-healthcare personnel. mRNA vaccines can be given in place of viral vector vaccinations because they show a reduced incidence of post-vaccination infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), also known as SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19 infection, is one of the most challenging public health problems in many regions of the world [1].

A breakthrough infection is a condition in which a patient who has received vaccinations contracts the same disease against which they were protected because the vaccine did not completely protect the patient. COVID-19 isn't a unique exception to this occurrence, which has been widely reported in the context of other viral and bacterial vaccinations [2].

The development of post-vaccination infections is also influenced by poor antibody generation brought on by relatively inefficient vaccines, an insufficient number of doses, and the passing of time after the vaccinations [3]. Minor antibody declines after immunity generated by vaccines do not always signify a complete fading of immunity because a long-lasting immunity against recurrent SARSCOV2 infection is usually feasible for up to eight months after receiving the vaccine via anti-S Memory B cells [4].

Objectives of the study

The present study was formulated to target the hospital attendants in Qena City to measure the prevalence of COVID-19 post-vaccination infection among the vaccinated participants and to identify possible related factors.

Material and method

A cross-sectional study involved 285 participants who had received the COVID-19 vaccines and were aged 18 years or older. Simple random sampling was used. The study's participants were chosen from attendants at Qena University hospitals. In this prevalence study, the appropriate sample size was determined using the straightforward formula below [5]:

where n is the sample size, Z is the standard normal variant (at 5% type 1 error (P< 0.05), it is 1.96, d (absolute error or precision) = 0.05, and p (reported COVID-19 infection after vaccination in a previous study done in Jordan) = 5%.

The level of confidence usually aimed for was 95%.

The sample size was increased to 285 participants.

Inclusion criteria

-

1.

Those who had received the COVID-19 vaccines and were at least 18 years old.

-

2.

Agreement to take part in the study.

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Individuals under the age of 18.

-

2.

Those who had not been vaccinated against COVID-19.

-

3.

Refusing to take part in the study.

Data collection

For collecting the data, a systematic questionnaire was used. It included the following items:

-

1.

Personal and demographic information, including name, age in years, sex, occupation, presence of chronic disease, and type of the chronic disease.

-

2.

The type of COVID-19 vaccine received.

-

3.

Number of doses of vaccine received.

-

4.

COVID-19 infection after vaccination.

-

5.

The duration between vaccination and catching the COVID-19 infection (in months).

-

6.

Management needed for COVID-19 cases after vaccination.

Most of participants who reported post vaccination infection were healthcare workers and diagnosis based on RT PCR for COVID-19 as it was available for them, while the diagnosis of other participants was based on their doctor’s diagnosis.

Ethical consideration

The research was approved by the ethical committee of the Qena Faculty of Medicine. The ethical approval code: SVU-MED-COM009-2-23-7-693. Oral consent was taken from the participants after explaining the aim of the study

Statistical analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS) version 26 was used to analyze the data. Frequencies and percentages were used to represent qualitative factors. Two qualitative data sets were compared using a chi-square test. The analysis of binary logistic regression was applied. The allowable margin of error was set at 5%, while the confidence interval was set at 95%. Therefore, a P value of 0.05 or less is regarded as significant.

Results

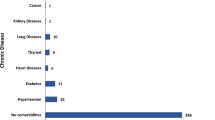

44.9% of our participants were in the age group of 18 to 27 years old. 37.9% of the participants were males. According to occupation, 79.3% of the participants were non healthcare workers. 14% of the participants had chronic disease. 47% of the participants received Inactivated vaccines (Sinopharm and Sinovac vaccines), 33.7% received Viral vector vaccines (Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine and Johnson's and Sputnik V vaccines), while those who received mRNA vaccines (Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines) were 19.3% of all vaccinated participants.

Most of our participants received two doses of the vaccination (86.7%). No participants received two different types of the COVID 19 vaccines. Of the 285 vaccinated participants, 39 (13.7%) reported contracting COVID-19 following their vaccination (Fig. 1). The median duration between vaccination and catching the COVID-19 infection was 3 months. According to management needed for COVID 19 cases after vaccination, most cases needed home treatment 35 (89.7%), while 4 (10.3%) did not need any treatment (Table 1).

Healthcare workers were more susceptible to COVID-19 infection after vaccination than non-healthcare workers (28.8% vs. 9.7%, respectively). 16.7% of participants who received Viral vector vaccines reported COVID-19 infection after vaccination, 15.7% of those who received Inactivated vaccines reported COVID-19 infection after vaccination; and only 3.6% of those who received mRNA vaccines reported COVID-19 infection after vaccination. There was no statistically significant association between COVID-19 infection after vaccination and either age groups, sex, or the number of doses of vaccine received by the participants (Table 2).

Logistic regression analysis of COVID-19 infection after vaccination among the different predictors showed that the participants who received Viral vector vaccines and those who received Inactivated vaccines reported COVID-19 infection after vaccination more than those who received mRNA vaccines by 5.790 (95% CI: 1.253–26.76) and 4.668 (95% CI: 1.038–20.988) times, respectively. Also, healthcare workers reported COVID-19 infection after vaccination more than non-health care workers by 3.859 times (95% CI: 1.854 1.854–8.035) (Table 3).

Discussion

The effectiveness of the global campaign to end the pandemic and its impacts will be limited by lower COVID-19 vaccine acceptance [6]. One of the main factors affecting the uptake of the COVID-19 vaccination is confidence in its efficacy in infection prevention [7].

Our study is a cross-sectional study conducted in Qena University Hospitals. The current study measured the COVID-19 post-vaccination infection reported by the vaccinated participants. The prevalence of COVID-19 post-vaccination infection was 13.7%. This finding was in line with a study carried out on COVID-19 infections emerging after vaccinations in healthcare and other workers in New Delhi, which found that 15 participants (13.3%) became infected with COVID-19 (two weeks after the second dose) [8]. The prevalence was higher than that of a Cross-Sectional Study carried out in Jordan, which revealed that 5% of vaccinated individuals contracted COVID-19 after receiving the COVID-19 vaccines [9].

Our study reported that, according to management needed for COVID-19 cases after vaccination, most cases needed home treatment (89.7%), while 4 (10.3%) did not need any treatment. whereas nobody needed hospital or ICU admission. The results were similar to a study done in Jordan that showed that the majority of participants (66%) received painkillers and rested at home without hospitalization or even visiting a doctor to ease post-vaccination infection, while 31% of participants just obtained rest at home without taking medicine at all [9]. Another study found that COVID-19 post-vaccination infections were less likely to require hospitalization and admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) than infections in non-vaccinated patients [10].

Our study reported that healthcare workers were more susceptible to COVID-19 infection after vaccination than non-healthcare workers. In the United Kingdom, a community-based, nested case-control study was carried out to identify risk factors and the disease profile of SARS-COV-2 infection following vaccination. It found that, with regard to healthcare workers, neither the positive nor the negative findings of a SARS-COV-2 test conducted at least 14 days after the first vaccination nor seven days or more after the second vaccine showed statistically significant differences [11]. Testing accessibility could be a source of bias. Healthcare personnel are more likely than the general population to report a positive SARS-COV-2 test [12], probably as a result of more testing and exposure.

Our study reported that according to the association between the type of COVID-19 vaccine received and the percent of vaccinated participants who reported post-vaccination infection, it was clear that Viral vector vaccines had the highest percent (16.7%), followed by Inactivated vaccines and mRNA vaccines (15.7% and 3.6%, respectively). In a study that detailed side effects and attitudes among Arab populations following the receipt of COVID-19 vaccines, it was found that, depending on the vaccine type, the proportion of participants who became infected with COVID-19 after vaccination varied. Among participants who received the AstraZeneca vaccination, the proportion of participants who experienced a breakthrough infection was the highest (8%) compared to only 3% of all participants who received the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine [13].

Conclusion

13.7% of the participants reported they contracted the COVID-19 infection later on after vaccination. The median time between receiving the COVID-19 vaccine and getting the infection was three months. Following vaccination, healthcare workers were more vulnerable to the COVID-19 infection than non-healthcare employees. Participants who received viral vector vaccinations, inactivated vaccines, or mRNA vaccines experienced post-vaccination infection at rates of 16.7%, 15.7%, and 3.6%, respectively.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets used and analysed during the current study are available from corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus 19

- mRNA:

-

Messenger RNA

- SARS-COV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

References

Agrawal R, Baghel AS, Patidar H, Akhani P (2023) Psychological impact of covid-19 pandemic on medical students of Madhya Pradesh, India. SVU Int J Med Sci 6(1):79–88. https://doi.org/10.21608/svuijm.2022.145271.1324

Mohseni Afshar Z, Barary M, Hosseinzadeh R, Alijanpour A, Hosseinzadeh D, Ebrahimpour S et al (2022) Breakthrough SARS-COV-2 infections after vaccination: A critical review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 18(5). https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2051412

McDonald I, Murray SM, Reynolds CJ, Altmann DM, Boyton RJ (2021) Comparative systematic review and meta-analysis of reactogenicity, immunogenicity and efficacy of vaccines against SARS-COV-2. npj Vaccines 6, 74(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-021-00336-1

Dan JM, Mateus J, Kato Y, Hastie KM, Yu ED, Faliti CE et al (2021) Immunological memory to SARS-COV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science 371(6529):eabf4063. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abf4063.

Charan J, Biswas T (2013) How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J Psychol Med 35(2):121–126. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.116232

Joshi A, Kaur M, Kaur R, Grover A, Nash D, El-Mohandes A (2021) Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, intention, and hesitancy: A scoping review. Front Public Health 9:698111. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.698111

Mohamed RA, Hany AMM, Nafady AA (2023) The acceptance and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine among the hospital attendants in Qena city. SVU Int J Med Sci 6(2):541–552. https://doi.org/10.21608/svuijm.2023.218410.1607

Tyagi K, Ghosh A, Nair D, Dutta K, Singh Bhandari P, Ahmed Ansari I et al (2021) Breakthrough COVID19 infections after vaccinations in healthcare and other workers in a chronic care medical facility in New Delhi, India. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev 15(3):1007–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2021.05.001

Hatmal MM, Al-Hatamleh MA, Olaimat AN, Hatmal M, Alhaj-Qasem DM, Olaimat TM et al (2021) Side effects and perceptions following COVID-19 vaccination in Jordan: A randomized, cross-sectional study implementing machine learning for predicting severity of side effects. Vaccines 9(6):556. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9060556

Mor V, Gutman R, Yang X, White EM, McConeghy KW, Feifer RA et al (2021) Short-term impact of nursing home SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations on new infections, hospitalizations, and deaths. J Am Geriatr Soc 69(8):2063–2069. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17176

Antonelli M, Penfold RS, Merino J, Sudre CH, Molteni E, Berry S et al (2022) Risk factors and disease profile of post-vaccination SARS-COV-2 infection in UK users of the COVID symptom study app: A prospective, community-based, nested, case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis 22(1):43–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(21)00460-6

Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Joshi AD, Guo C-G, Ma W, Mehta RS et al (2020) Risk of covid-19 among frontline healthcare workers and the general community: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 5(9):e475–e483. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.29.20084111

Hatmal MM, Al-Hatamleh MA, Olaimat AN, Mohamud R, Fawaz M, Kateeb ET et al (2022) Reported adverse effects and attitudes among Arab populations following covid-19 vaccination: A large-scale multinational study implementing machine learning tools in predicting post-vaccination adverse effects based on predisposing factors. Vaccines 10(3):366. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10030366

Funding

Nill.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RA made a substantial contribution to the conception of the work, analysis and interpretation of data and drafted the work. AM made a substantial contribution to the conception of the work and has been involved in data analysis. AN was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was approved by the ethical committee of the Qena Faculty of Medicine. The ethical approval code: SVU-MED-COM009-2-23-7-693.Oral consent taken from participants to be involved in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, R.A., Hany, A.M.M. & Nafady, A.A. COVID-19 Post- vaccination infection among hospital attendants in Qena city. Egypt J Bronchol 17, 69 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43168-023-00244-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43168-023-00244-z