Abstract

Background

The ability of computed tomography (CT) in illustrating the pathology of lung parenchyma in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was discussed previously in many articles. However, the correlation between airflow limitation that is evaluated by spirometry and its corresponding airway diameter that is measured by multislice computed tomography (MSCT) still under investigation. Therefore, the objective of our study was to answer the questions about possible correlation between forced expiratory volume in first second (FEV1%), forced vital capacity (FVC%), FEV1/FVC, and peak expiratory flow25–75% (PEF25–75%), both before bronchodilator and post it with the diameters of airway at 3 different levels either during inspiratory or expiratory phase of respiration.

Results

The quantitative MSCT results at RB1 (apical bronchus of the right upper lobe), RB10 (the posterior basal bronchus of the right lower lobe), and LB3 (the anterior bronchus of the left upper lobe) showed weak positive correlation with FEV1% during inspiratory phase of respiration (r = 0.19, 0.20, and 0.18; P = 0.23, 0.22, and 0.26 respectively), but this correlation became more stronger and significant during expiratory phase of respiration (r = 0.76, 0.78, and 0.66; P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Expiratory CT parameters were significantly correlated with the predicted peak expiratory flow in 1 s.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The global definition of COPD describes precisely it as a general inflammatory disorder which is characterized by progressive airflow limitation that is not fully reversible. The limitation of airway results from remodeling of small airways as well as emphysema of lung parenchyma. The two previous pathologies could be discriminated clinically but not by pulmonary function tests despite the importance of that difference as regarding the treatment plans [1]. The diagnosis of COPD based primarily on pulmonary function test; hence, spirometry was the commonest assessment tool in detecting the severity of airway obstruction because it is simple, non-invasive, and easily applicable [2]. The continuous changes of airway morphology and parenchymal pathology added more different diagnostic demand, so the CT closes that gap by adding more important details. Hence, the CT was used for classification of COPD patients into different phenotypes: phenotype A that has minimal emphysema with or without airway disease, phenotype E that has emphysema without airway disease, and finally phenotype M as a mixed form [3, 4]. The ability of CT in establishing the differences between airway predominant disease from emphysema predominant type was highly effective, and thus enforce the researchers to discuss many possibilities and put different hypotheses to answer the quotations about the correlations between size of airway diameters that is measured by MSCT and the corresponding forced expiratory flow rate in 1 s [5]. Another studies looking for the correlation of MSCT readings with lung capacity and different lung volumes [6, 7].

From that point of view, our study was designed to answer the questions about possible correlation between FEV1%, FVC%, FEV1/FVC, and PEF25–75% both before bronchodilator and post it with the diameters of airway at 3 different levels either during inspiratory or expiratory phase of respiration.

Methods

Study design and population

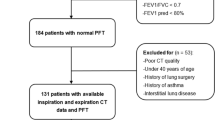

It is a prospective cross-sectional study that was conducted in Chest Department, Kasr El-Aini Hospital, Cairo University and El Mahalla El Kubra Chest Hospital. It included stable COPD patients based on their past medical history of the disease, and they came for routine visits in outpatient clinic from January 2016 until the end of January 2017. The referred subjects asked for informed written consent after fulfilling the inclusive and exclusive criteria of the study. The study was approved by the ethical committee of Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University.

Inclusive criteria

-

All stable COPD patients that lastly confirmed to have the disease based on spirometry and past clinical history according to GOLD 2015 (as the study began January 2016)

-

Ability to perform MSCT

Exclusive criteria

-

COPD patients associated with other chest diseases that affect the lung volumes as collapse, consolidation, effusion, malignancy, and thoracic cage deformity

-

Associated respiratory failure

All patients were subjected to complete spirometry evaluation pre- and post- bronchodilator application using the Spirometry system (Masterscreen 2001, version 4.5, Erich Jaeger GMBH, Germany) in triple reading records, and the highest values (FEV1%, FVC%, FEV1/FVC, and FEF25–75%) were selected to correlate with CT’s quantitative data readings.

MSCT examination

All patients underwent MSCT chest at both inspiratory and expiratory phases in supine position without any contrast media. All CT scan films examined by the same team of diagnostic radiologist, and viewed at the same viewer system: GE Light speed Ultra 8 slice CT Scanners (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA). CT parameters were as follows: tube voltage about 120 kV with current about 80 mA, scan range from lung apex to the diaphragm, pitch 0.875, B31f reconstruction kernel, section thickness 1–1.25 mm, collimator width 1 mm, and a gantry rotation speed of 0.75 s. Furthermore, the raw data of CT reconstructed to 1.25 mm section thicknesses using a standard algorithm. We measured airway internal diameters in some selected areas: the apical bronchus (RB1) of the right upper lobe, the posterior basal bronchus (RB10) of the right lower lobe, and the anterior bronchus (LB3) of the left upper lobe, which were perpendicular to the long airway axis. After that, we traced it manually; hence, the bronchial internal diameters (L) were assessed by standard.

The statistical analysis and sample size were calculated using Minitab 17.1.0.0 for windows (Minitab Inc., 2013, Pennsylvania, USA). Continuous date was presented as mean and SD; the normality of data were examined using Shapilo–Weilk test. Paired t test used to compare between two means before and after intervention. Pearson correlation coefficient used to estimate the linear relationship between two or more numerical variables; the sign before the “r” represents the direction of relationship. All tests were two sided; P is considered significant if < 0.05.

Results

Patient’s characteristics

Forty male patients with stable COPD condition enrolled to the study, with mean age about 61 years old and ranged from 40 to 81 years. The spirometry readings, pre- and post-bronchodilator application, were summarized in Table 1, as well as the inter-luminal diameters at the selected areas in inspiratory and expiratory phases of respiration.

Effect of bronchodilator in spirometry reading

After bronchodilator application, the spirometry was repeated and showed significant improvement in FEV1%, FEV1/FVC, and PEF25–75% as demonstrated in (Table 2), with P < 0.001, < 0.001, and 0.04 respectively.

Inter-luminal size and correlation with spirometry function

Considering the correlation between the predicted peak expiratory flow in 1st second (FEV1%) and the corresponding inter-luminal size at the chosen levels (RB1, RB10, and LB3) in inspiratory stage of respiration, the correlation was positive but not significant enough (Table 3), P = 0.23, 0.22, and 0.26 respectively. On the other hand, during expiratory phase, the linear relationship was positive and significant, P < 0.001 for all (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Limitation of airflow is a complex pathology that is caused by both airway remolding and emphysema [6]. The results of the current work demonstrated the correlation between CT detected airway luminal area at expiratory stage of respiration and the FEV1% which was significant in a positive way, while the corresponding correlation at inspiratory phase was not significant. Hence, the thickness of air wall added more limitation force during expiration. Moreover, the thickness of airway wall as well as the collapsibility power of bronchi magnified the narrowing in expiratory phase than in inspiratory one. Furthermore, with decreasing the size of airway luminal area as descending from third generation level to fifth one, the correlation was improved which finally supports the current concept; the sub-segmental bronchus affecting the obstruction level of COPD rather than the segmental bronchus. The present data is supported by previous studies [8, 9], while Hasegawa et al. found a contrast concept, hence, he found a close significant correlation between FEV1 and luminal diminution at inspiratory phase of respiration especially at sub-segmental level of bronchi. The difference might be referred to many factors: first, individual variations; second, airway heterogeneity in COPD patients; and third, patients assortment. Conventional pulmonary functions cannot provide a restrict regional information which had been given by quantitative CT analysis, so the past few the attention toward therapeutic medications that particularly deal with airflow restriction in COPD [10, 11]. From that point of value, the different studies focused on quantitative CT analysis to evaluate the relative effectiveness of drug on managing airway hyper-reactivity using inspiratory and expiratory volumetric study with multislice CT because this technique allows clue of specific individual airways that relate to airflow restriction [12]. Finally, in spite of using FEV1 parameter as an essential value that determined airflow obstruction in COPD studies, its role became imperfect, as, it showed a little capability in determining regional variations in lung diseases beside the airway disorders. A lot of airway disorders as smooth muscle hypertrophy, fibrosis, mucous metaplasia, inflammation, and loss of bronchiolar tethering with alveolar destruction needed more quantitative analyses by using MDCT, which help in differentiating different COPD phenotypes [7]. Our study faced many limitations; the first one was detection of just three bronchial levels: B1, B3, and B10. The second tie was fearing from amounts of radiation exposure during the examination of pairing inspiratory phase and expiratory phase. And as mentioned before, the pathogenicity of COPD made that the level of obstruction could be at different lobe of bronchi rather than what we selected in our study, beside that the severity of the disease and its distribution might be affect the results.

Conclusions

At the end, we can conclude that the correlation between CT detected airway luminal area at expiratory stage of respiration and the FEV1% was significantly positive, while at inspiratory phase was not; moreover, with decreasing the size of airway luminal area as descending from third generation level to fifth one, the correlation was improved. The data gave a promising idea about the quantitative CT reading during follow-up of patients with COPD, and subsequently open the door for further researches that discussing its role on different parenchymatous and airway diseases.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- RB1:

-

Apical bronchus of the right upper lobe

- RB10:

-

The posterior basal bronchus of the right lower lobe

- LB3:

-

The anterior bronchus of the left upper lobe

- FEV1:

-

Forced expiratory volume in first second

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- PEF:

-

Peak expiratory flow

References

Patel AR, Patel AR, Singh S, Singh S, Khawaja I. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease: the changes made. Cureus. 2019 Jun;11(6).

Diaz O, Villafranca C, Ghezzo H, Borzone G, Leiva A, Milic-Emil J, Lisboa C (2000 Aug 1) Role of inspiratory capacity on exercise tolerance in COPD patients with and without tidal expiratory flow limitation at rest. European Respiratory Journal. 16(2):269–275

Fujimoto K, Kitaguchi Y, Kubo K, Honda T (2006 Nov) Clinical analysis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes classified using high-resolution computed tomography. Respirology. 11(6):731–740

Han MK, Kazerooni EA, Lynch DA, Liu LX, Murray S, Curtis JL, Criner GJ, Kim V, Bowler RP, Hanania NA, Anzueto AR (2011 Oct) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in the COPD Gene study: associated radiologic phenotypes. Radiology. 261(1):274–282

D’Anna SE, Asnaghi R, Caramori G, Appendini L, Rizzo M, Cavallaro C, Marino G, Cappello F, Balbi B, Di Stefano A (2012) High-resolution computed tomography quantitation of emphysema is correlated with selected lung function values in stable COPD. Respiration. 83(5):383–390

Šileikienė V, Urbonas M, Matačiūnas M, Norkūnienė J (2017) Relationships between pulmonary function test parameters and quantitative computed tomography measurements of emphysema in subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Acta medica Lituanica. 24(4):209

Koo HJ, Lee SM, Seo JB, Kim N, Oh SY, Lee JS, Oh YM (2019 Apr 1) Prediction of pulmonary function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: correlation with quantitative CT parameters. Korean journal of radiology. 20(4):683–692

Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, Woods R, Elliott WM, Buzatu L, Cherniack RM, Rogers RM, Sciurba FC, Coxson HO, Paré PD (2004 Jun 24) The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 350(26):2645–2653

Hogg JC, Macklem PT, Thurlbeck WM (1968 Jun 20) Site and nature of airway obstruction in chronic obstructive lung disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 278(25):1355–1360

Sin DD, McAlister FA, Man SP, Anthonisen NR (2003 Nov 5) Contemporary management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: scientific review. Jama. 290(17):2301–2312

Burge PS, Calverley PM, Jones PW, Spencer S, Anderson JA, Maslen TK (2000 May 13) Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study of fluticasone propionate in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the ISOLDE trial. Bmj. 320(7245):1297–1303

Goldin JG, Tashkin DP, Kleerup EC, Greaser LE, Haywood UM, Sayre JW, Simmonsb MD, Suttorp M, Colice GL, Burgt JA, Aberle DR (1999 Dec 1) Comparative effects of hydrofluoroalkane and chlorofluorocarbon beclomethasone dipropionate inhalation on small airways: assessment with functional helical thin-section computed tomography. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 104(6):s258–s267

Acknowledgements

The author was grateful for statistical analysis and data interpretation that provided by Dr. Asmaa Ali, MSc. Ministry of Health and Population, Chest Directorate, Abbassia Chest Hospital.

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HH, AI, and HM had put the design and frame of the work. MM had collected, analyzed, and interpreted data regarding COPD patients who had done pulmonary function tests and CT chest. HM had drafted the work, revised it, and was a major contributor in writing manuscript. AI was a major contributor in interpreting radiological data. HH had read and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The referred subjects were asked for informed written consent after fulfilling the inclusive and exclusive criteria of the study. The study was approved by the ethical committee of Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University. IRB was not necessary according to national regulations at time of starting the study. Committee’s reference number is not available.

Consent for publication

Was taken from all authors

Competing interests

None

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahros, M., Hosny, H., Ismail, A. et al. Airflow limitation: is there a correlation between spirometry and quantitative computed tomography measurements in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?. Egypt J Bronchol 14, 8 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43168-020-00011-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43168-020-00011-4