Abstract

Background

SAPHO syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis) is a rare, heterogeneous, self-limited disease of unknown etiology. It involves progressive bone and joint damage, and skin and bone lesions may occur at different times in the course of the disease. Skin lesions are characterized by neutrophil dermatosis. Its management is empirical and mainly symptomatic, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the first-line treatment.

Case presentation

Forty-seven-year-old female presented with a 7-year history of costochondral pain. It had progressive onset, chronical course, with no other associated symptoms, and no other joint involvement. She was treated with intermittent NSAID (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), which provided only partial pain relief; there was bilateral tender swelling of the sternoclavicular region, the skin over the sternoclavicular area was slightly erythematous, but there were no other skin lesions, and based on imaging findings, a diagnosis of SAPHO syndrome was established. The patient received an infusion of zoledronic acid with subsequent complete resolution of her chest wall symptoms, and completely improved after 3 days.

Conclusions

This case is considered atypical presentation of SAPHO syndrome, without skin changes, long-term persistence of refractory symptoms, and the diagnosis was established by imaging, with complete resolution after zoledronic acid infusion. SAPHO is a differential diagnosis in patients with chronic costochondritis. Therapeutic failure to NSAID is a key to its diagnostic suspicion. Also, early diagnostic suspicion is associated with better outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

SAPHO syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis) is a rare self-limited disease of unknown etiology; it can last for 4 to 5 years on average. Its presentation is heterogeneous and overlaps with other conditions, most often occurs in young and middle-aged persons, and also involves progressive bone and joint damage [1,2,3]. Skin and bone lesions may be present at different times. Skin manifestations include signs of neutrophilic dermatoses such as palmoplantar pustulosis (most common), psoriasis vulgaris, severe acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa [1]. Regarding bone involvement, most commonly affected sites are sternoclavicular junction, followed by spine and sacroiliac joints [2]. Diagnosis is established on the basis of at least one of the following criteria: (1) multifocal osteitis with or without skin symptoms; (2) sterile acute/chronic joint inflammation with either pustules or psoriasis of palms/soles, or acne, or hidradenitis suppurativa; (3) and/or sterile osteitis and any of the above skin manifestations [4]. Also, lab tests are not useful for diagnosis [1].

There is limited evidence for management which is empirical and mainly symptomatic. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) are the first-line treatment; alternative options include intra-articular or systemic corticosteroids, doxycycline, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) such as methotrexate, sulfasalazine, ciclosporin, and leflunomide [1, 3]. Bisphosphonates have been reported effective for transient pain relief and partial or complete remission over time [5]. And, anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha agents and anakinra have been reported effective in case series or reports of refractory SAPHO [6].

SAPHO syndrome is rare by itself. However, we present a case whose clinical characteristics and management make it different from what has been described to date, including atypical manifestations, without skin changes, and long-term persistence of refractory symptoms, in whom the diagnosis was reached after suggestive imaging findings, achieving complete resolution after zoledronic acid infusion.

Case description

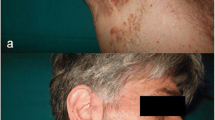

We report the case of a 47-year-old female, who presented to the rheumatology clinic with a 7-year history of costochondral pain. It had progressive onset, chronical course, with no other associated symptoms, and no other joint involvement. She had been treated for costochondritis or Tietze syndrome with intermittent NSAID (diclofenac, 50 to 150 mg daily), which provided only partial pain relief. She had no other significant past medical history. On exam, there was bilateral tender swelling of the sternoclavicular region (Fig. 1). Examination of peripheral joints was unremarkable. The skin over the sternoclavicular area was slightly erythematous, but there were no other skin lesions. Serum CRP (C-reactive protein) was normal, and the patient tested negative for RF (rheumatoid factor) and HLAB27 (human leukocyte antigen B27). 99mTc (technetium-99m) bone scintigraphy showed the characteristic bullhead sign of tracer uptake in the sternoclavicular region (Fig. 2). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax demonstrated osteolysis and hyperostosis at the sternoclavicular junction (Fig. 3). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of SAPHO syndrome was established. The patient received an infusion of zoledronic acid with subsequent complete resolution of her chest wall symptoms and completely improved after 3 days.

Axial CT image of thorax showing hypertrophy of the manubrium and irregularities, fusion on edges of manubriosternal and bilateral sternoclavicular joints. Arthropathy with ankylosis at bilateral sternoclavicular joints. Also, a section through the right sternoclavicular joint reveals osteolysis (→) and hyperostosis (▼)

Discussion

Some characteristics of this case are striking and deserve to be analyzed in the light of current knowledge; one of the characteristics that make it unique is the therapeutic response to zoledronic acid; also, it presented multifocal without skin changes and persistence of refractory symptoms longer than 5 years, and imaging was required to establish the diagnosis. On the other hand, some of its usual characteristics included that it was a woman older than 40 years, with osteitis in the anterior thoracic wall and without initial response to NSAID. All of the above shows us that we cannot always expect typical findings in this entity and that we must have a high index of clinical suspicion.

The term SAPHO was introduced by Chamot et al. in the late 1980s to describe a syndrome characterized by the combination of chronic inflammatory osteoarticular lesions and neutrophilic skin eruptions [7, 8], but similar associations had been reported in the literature going back to the 1960s [9]. Synovitis and osteitis in SAPHO predominantly affect the anterior chest wall (68–83%), spine (19–66%), and sacroiliac joints (13–40%) [10]. The symphysis pubis, long bones, and temporomandibular joints are less frequently involved. Peripheral arthritis may occur in up to one third of patients, typically affecting the knees or wrists [10]. Joint and bone inflammation in SAPHO manifest clinically as pain, swelling, and stiffness. The osteitis in SAPHO is sterile and may involve the cortex and the medulla, often adjacent to involved joints. Bone inflammation may result in the development of lytic lesions as well as formation of new bone causing bony prominence (hyperostosis) and joint ankylosis. Palmoplantar pustulosis (46–60%) and severe acne (5–39%) are the most common skin manifestations in SAPHO [10]. Psoriasis vulgaris, hidradenitis suppurativa, pyoderma gangrenosum, and sweet syndrome are less frequently found. The skin disease in SAPHO may develop before, concomitantly with or after the osteoarticular disease features in roughly equal proportions [11]. Importantly, patients with SAPHO do not always present with all of the features defining the syndrome. In two large case series, 19/120 (15.5%) and 14/71 (19.7%) SAPHO patients had no skin lesions at all [11, 12].

Incomplete presentations of the SAPHO syndrome, in particular when typical skin findings are absent, may be confused with other entities such as costochondritis resulting in delayed or missed diagnosis. Costochondritis is characterized by anterior chest wall pain without local swelling that is reproduced by palpation of the involved costosternal joints. In 90% of patients, more than one joint is affected, typically at the level of the second through fifth rib. Involvement of the second or third costochondral junction with local swelling is called Tietze syndrome. Costochondritis may result from chest wall trauma, chronic cough, or sports-related overuse injury, but most commonly is idiopathic. Women older than 40 are frequently affected. The majority of costochondritis cases will resolve over the course of 1 year. Long-term persistence of symptoms (7 years in our patient) should be considered a red flag suggesting an alternative diagnosis [13]. Sternoclavicular swelling is also atypical for simple costochondritis.

Imaging studies are important in making a diagnosis of SAPHO. Radiographs are typically normal early on but can show osteolytic lesions with or without sclerotic margins, joint erosions, or ankylosis at later stages. Whole-body 99mTc scintigraphy is particularly useful. The bullhead sign is a characteristic pattern of high tracer uptake in the sternocostoclavicular region, with the manubrium sterni representing the skull and the sternoclavicular joints and adjacent clavicles forming the horns [14]. This configuration is virtually pathognomonic for SAPHO. While sensitivity is not 100%, a bullhead may be present in SAPHO patients who do not have anterior chest wall symptoms, and whole-body bone scintigraphy may reveal clinically silent lesions elsewhere. CT scanning may demonstrate bone erosions, joint space narrowing, ligament ossifications, subchondral sclerosis, and periosteal new bone formation at affected sites.

NSAID are typically used as first-line drugs in SAPHO patients but do not sufficiently control pain in half of the patients. Other treatment options include colchicine, corticosteroids, DMARD such as methotrexate and sulfasalazine, and bisphosphonates [5]. Randomized controlled drug trials have not been performed in SAPHO. However, efficacy of bisphosphonate therapy has been documented by multiple case reports. Most of these patients were treated with pamidronate, but other bisphosphonates including zoledronic acid, as in our patient, may work equally well [5]. TNF (tumor necrosis factor) inhibitors have been used in refractory cases but may exacerbate cutaneous manifestations [6].

Conclusion

SAPHO is an important differential diagnosis in patients with chronic costochondritis. Persistence of symptoms and poor response to treatment with NSAID should raise suspicion for this diagnosis even in the absence of the typical skin features. Bisphosphonates are an alternative to be considered in refractory cases. Also, considering a SAPHO diagnosis may permit treating the patient more effectively, as documented in this case report.

Availability of data and materials

The data and material available for publication are in the manuscript and no information is being omitted.

Abbreviations

- SAPHO:

-

Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis

- NSAID:

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- DMARD:

-

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- RF:

-

Rheumatoid factor

- HLA-B27:

-

Human leukocyte antigen B27

- 99mTc :

-

Technetium-99m

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

References

Marzano AV, Borghi A, Meroni PL, Cugno M (2016) Pyoderma gangrenosum and its syndromic forms: evidence for a link with autoinflammation. Br J Dermatol 175(5):882–891

Khanna L, El-Khoury GY (2012) SAPHO syndrome--a pictorial assay. Iowa Orthop J 32:189–195

Liu S, Tang M, Cao Y, Li C (2020) Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis syndrome: review and update. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 12:14–15

Kahn MF, Khan MA (1994) The SAPHO syndrome. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol 8(2):333–362

Colina M, La Corte R, Trotta F (2009) Sustained remission of SAPHO syndrome with pamidronate: a follow-up of fourteen cases axnd a review of the literature. Clin Exp Rheumatol 27(1):112–115

Massara A, Cavazzini PL, Trotta F (2006) In SAPHO syndrome anti-TNF-α therapy may induce persistent amelioration of osteoarticular complaints, but may exacerbate cutaneous manifestations. Rheumatology 45(6):730–733

Chamot AM, Benhamou CL, Kahn MF, Beraneck L, Kaplan G, Prost A (1987) Le syndrome acné pustulose hyperostose ostéite (SAPHO). Résultats d'une enquête nationale. 85 observations [Acne-pustulosis-hyperostosis-osteitis syndrome. Results of a national survey. 85 cases]. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic 54(3):187–96. French. PMID: 2954204

Benhamou CL, Chamot AM, Kahn MF (1988) Synovitis-acne-pustulosis hyperostosis-osteomyelitis syndrome (SAPHO). A new syndrome among the spondyloarthropathies? Clin Exp Rheumatol 6(2):109–112 PMID: 2972430

Windom RE, Sanford JP, Ziff M (1961) Acne conglobata and arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 4(6):632–635

Aljuhani F, Tournadre A, Tatar Z, Couderc M, Mathieu S, Malochet-Guinamand S et al (2015) The SAPHO syndrome: a single-center study of 41 adult patients. J Rheumatol 42(2):329–334

Hayem G, Bouchaud-Chabot A, Benali K, Roux S, Palazzo E, Silbermann-Hoffman O et al (1999) SAPHO syndrome: a long-term follow-up study of 120 cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 29(3):159–171

Colina M, Govoni M, Orzincolo C, Trotta F (2009) Clinical and radiologic evolution of synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis syndrome: a single center study of a cohort of 71 subjects. Arthritis Care Res 61(6):813–821

Proulx AM, Zryd TW (2009) Costochondritis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician 80(6):19817327

Freyschmidt J, Sternberg A (1998) The bullhead sign: scintigraphic pattern of sternocostoclavicular hyperostosis and pustulotic arthroosteitis. Eur Radiol 8(5):807–812

Acknowledgements

J.E. has been supported by the Rheumatology Research Foundation and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R03AR066357).

Funding

None declared by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.P.I, H.C, V.R., J.S.F.O, and S.M. collected data. V.P.I, J.S.F.O, and J.E. wrote the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The informed consent of the patient was obtained. This case report was approved by the research committee of La Sabana University, Chía, Cundinamarca, Colombia.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Parra-Izquierdo, V., Cubides, H., Rivillas, V. et al. SAPHO—a diagnosis to consider in patients with refractory costochondritis. Egypt Rheumatol Rehabil 49, 44 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43166-022-00144-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43166-022-00144-y