Abstract

Background

Light is the critical factor that affects the eye's morphology and auxiliary plans. The ecomorphological engineering of the cornea aids the physiological activities of the cornea during connections between photoreceptor neurons and light photons. Cornea was dissected free from the orbit from three avian species as ibis (Eudocium albus), duck (Anas platyrhynchus domesticus) and hawk (Buteo Buteo) and prepared for light and scanning electron microscopy and special stain for structural comparison related to function.

Results

The three investigated avian species are composed of three identical layers; epithelium, stroma, and endothelium, and two basement membranes; bowman's and Descemet’s membrane, separating two cellular layers, except for B. buteo which only has a Descemet’s membrane. The corneal layers in the investigated species display different affinity to stain with Periodic Acid Schiff stain. The external corneal surface secured by different normal epithelial cells ran from hexagonal to regular polygonal cells. Those epithelial cells are punctured by different diameter microholes and microplicae and microvilli of various length. Blebs are scarcely distributed over their surface. The present investigation utilized histological, histochemical and SEM examination.

Conclusions

The study presents a brief image/account of certain structures of cornea for three of Avian’s species. Data distinguish the anatomic structures of the owl's eye. The discussion explains the role of some functional anatomical structures all through the vision.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Background

Light is the crucial factor that influences the eye's morphology and structural plans [1]. Eye's architecture, inception and level of sensibility fluctuate extraordinarily relying upon assortment ecological conditions and functional impediments [2, 3]. Tamayo-Arango, Baraldi-Artoni [4] consider the glop as a vital biologic organ in most vertebrate. Its ecomorphological architecture represents the features of the setting and the species' lifestyle in an evolutionary context. The ecomorphological architecture of the cornea, illustrated by Tamayo-Arango, Baraldi-Artoni [4], assists in the physiological actions of the cornea during interactions between photoreceptor neurons and light photons (refraction capacity, biochemical responses, lodging, etc.). Clark [5] considers the corneal tissue a powerful defense in the front of the eye, whereas the cornea is able to protect the eye's inner components and has a protective function based on the outer eye tunic's mechanical strength. Statistically, Meek [6] pointed out that the cornea forms only 15% of the eye ball's outer layer, whereas the sclera forms the remaining 85%.

Theoretically, the refractive characteristics of the cornea are controlled by Snell's law, according to Leonard and Meek [7], which states that the angle of refraction is proportional to the difference in refractive indices between the two media when light moves between two isotropic media, such as water, glass or air. Therefore, Land and Nilsson [3] concluded that the noteworthy variety in these refractive records constrained the functioning vertebrate eyes in the two media to be hyperopic in water and myopic in air.

The two cellular layers epithelium and endothelium are more characterized by higher rate of corneal metabolism of glycogen [8]. Glycogen constitutes the primary source of energy for all corneal layers in different vertebrates; whereas, the main bulk of the polysaccharides is represented in the corneal stroma [9]. Assortment environmental conditions affect the appearance of corneal microprojection [10]. Arrangement of microprojection may be affected by annexed of the eye of birds, like the need for lubrication during flight, reduction of friction, and the presence or absence of nictating membrane and eyelids [11].

With the aid of an adequate understanding of the detailed morphological and physiological patterns of corneal structure, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) studies can underline such gaps. In this manner, the present study aims to delineate and investigate the distinctive creation of the corneal layers using histological, histochemical and SEM examinations. Consequently, the present research considers their natural environmental conditions in the investigations and discussion sections. In addition, the present Avian’s cornea structures will be compared and integrated with the published outcomes in the reviewed studies.

2 Methods

2.1 Experimental animals

Three avian families as follows: (1) Threskiornithidae (Eudocium albus), (2) Anatidea (Anas platyrhynchus domesticus) and (3) Accipitriformes (Buteo Buteo) were collected from different locations of Egypt. They were identified according to recent reviews by Goodman and Meininger [12] and [13]. Ten adult birds from each species were investigated and weighting 450 ± 12.9 g in Eudocium albus, 1000 ± 250 g in Anas platyrhynchus domesticus and 2.000 ± 480 g in Buteo Buteo. Their common name, distribution in Egypt and habitat were documented in the present investigation as follows:

2.1.1 Family Threskiornithidae

Eudocium albus (Linnaeus, 1758). The Common name is Whit ibis. They distributed in the agriculture field along Nile River in Egypt, such as Behira (30.8481° N, 30.3436° E) and Sharquia (30.7327° N, 31.7195° E). They were commonly found in muddy pools, on mudflats and even wet lawns and have diurnal activity [14].

2.1.2 Family anatidea

Anas platyrhynchus domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758). Common name is Pekin duct. They distributed in the agriculture field along Nile River in Egypt, such as Beni_Suef (29.0661° N, 31.0994° E) and El Gharbia (30.8754° N, 31.0335° E). They have coastal habitats such as beaches, marshes and ponds and have diurnal activity (Long, 1981).

2.1.3 Family accipitriformes

Buteo Buteo (Linnaeus, 1758). Common name is Common buzzard. They distributed in Sinai (29.5000° N, 34.0000° E). They inhabit the forests, medium altitude mountains. Nests in trees and among rocks in treeless areas. They activated all day with weight [15].

2.2 Experimental methods

After enucleation the corneas were dismembered free from the orbit with a sharp out zor blade and prepared for histological, histochemical and scanning electron microscopy investigation as pursues:

2.2.1 Histological sections preparation

The fixed specimens of the cornea were washed to remove the excess of the used fixative. They were then dehydrated in ascending grades of ethyl alcohol 70, 80, 90 and 95% for 45 min each, then in two changes of absolute ethyl alcohol each for 30 min. This step was followed by clearing in two changes of xylene, each for 30 min. The tissues were then impregnated with paraplast plus (three changes) at 60 °C for three hours and then embedded in paraplast plus. Sections of 4 to 5 µm thickness were prepared with a microtome and stained with haematoxylin and eosin for histopathological examination[16]. After light examination for the corneal histological sections; the presence and absence of different layers were recorded as follows: absent (−); one layer (+); two layers (++) and three layers (+++).

2.2.2 Histochemical sections preparation by periodic acid-Schiff's [17]

The fixed specimens de-waxicated by xylene and rehydrated through graded ethanol to water. Then they oxidized with 1% aqueous periodic acid solution (H5IO6; WINLAB; Leicestershire, UK) for five minutes. After that, they were rinsed in distilled water and the sections were covered with Schiff's reagent for 10–15 min then rinsed in running tap water for five minutes. Finally, the specimens were dehydrated, clear with xylene, mounting, and covered slipping. The sections were ready for examining by light microscope [18, 19]. The degree of carbohydrates was evaluated and represented as − = absence; + = mild; ++ = moderate and +++ = high.

2.2.3 Preparation for scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The whole eye was immediately fixed overnight with modified Karnovsky solution (2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde containing 0.1 M cacodylate-buffer, pH 7.4). The fixed specimens were then washed in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, and post-fixed in cacodylate-buffered solution of 1% osmium tetroxide at 37 °C for 2 h. The corneal specimens were rinsed in increasing concentrations of ethanol to commence dehydration which the first rinsed in 50% ethanol for 5 min; then 3 times for 5 min with 70% ethanol; rinsed 3 times for 5 min with 90% ethanol; rinsed 2 times for 5 min in 100% ethanol; and finally rinsed 2 times for 10 min in 100% ethanol (molecular sieve) all ethanol was removed from the samples and replaced with hexamethyldisilane (HMDS) in fume hood and left for 10 min. The base of the metal SEM stubs was labeled and applied double-sided conductive carbon tape to the top of the stubs. The dried specimens were then sputtered with gold in Joel fine coat Ion Sputter (SPI-Module). Specimens were then examined and photographed using standard microscope operating procedures JEOL SEM (JSM-5400 LV) for visualization of specimens in the Microanalysis Centre, Faculty of Science, Beni-Suef University, Beni-Suef Egypt. The analysis was commenced at low magnification, then the magnification increased gradually at an accelerating voltage of 15kv (JSM.5400LV, JEOL) [20, 21].

2.2.4 Image analysis

The anterior surface of the investigated cornea of each studied species were examined by JEOL (JSM with accelerating voltage 5400 LV). The area of the individual epithelial cells (µm2) and the number of cells were measured [22]. Moreover, the mean of epithelial cell density was calculated in additional to diameters of both microholes and blebs. These image analyses were digitally recorded using Image J software.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using one- way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Mean for ten readings for corneal surface for each parameter (microholes and blebs) at least for measuring. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation [23]. Values of P > 0.05 were considered statistically non-significant, while values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Histological observations

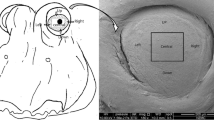

The present cornea data of the types of Avian, for example: Eudocimus albus, Anas platyrhunchus and Buteo buteo, delineated the upper epithelium layer, the middle center hypocellular stroma and the ended endothelium layer (Fig. 1). Epithelial layer is arranged as one layer of basal columnar cells in both E. albus and A. platyrhunchus, then two layers of polyhedral cells in E. albus, but three layers in A. platyrhunchus. Furthermore, both of E. albus and A. platyrhunchus’s epithelial layer is terminated with one row of flat squamous cells. Epithelium B. buteo was formed of four layers of oblate squamous cells.

Stromal lamellae were arranged uniformly with scattering keratocytes in E. albus and A. platyrhunchus; however, it was distinguished into two zones; condensed outer lamellar zone with compact collagen fiber and light inner lamellar zone with loose collagen fiber. Bowmen’s and Descemet’s membranes were shown only in E. albus, A. platyrhunchus and B. buteo; however, Bowman's membrane was absent in B. buteo (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Table 1 illustrates the variance of the epithelial thickness in the investigated avian species, in the statistical analysis (P < 0.05) ranging from 235.5 ± 8.4 μm in E. Albus,346.8 ± 41.3 μm in B. Buteo, and 262.6 ± 21.9 μm in A. platyrnchus. It occupied 5% of the complete avian cornea density.

Avian's B. Buteo reported an elevated statistical variability in its stromal layer, with a thickness of 5972.8 ± 472.1 μm, followed by E. albus with a thickness of 4403.0 ± 348.8 μm, whereas the smallest stroma thickness was 4006.6 ± 247.9 μm in A. platyrnchus (Table 2).

Furthermore, the studied species’ endothelium layers were 50.2 ± 2.1; 56.7 ± 2.7 and 65.7 ± 3.2 μm in E. albus; A. platyrnchus and B. Both buteo, respectively. Table 2 shows the elevated statistical variability (P > 0.001) of B.buteo with the other two species investigated and shows that the endothelium is about 1% of the total density of the examined cornea.

3.2 Histochmical observations

With regard to avian cornea, Fig. 2 and Table 3 show the epithelium layer, which showed an intense quantity of PAS-positive materials in Eudocimus albus; whereas, it was mildly stained in Buteo buteo, and slightly stained in Anas platyrhynchus (Fig. 2). There was a high affinity to PAS stain in the stroma of A. platyrhynchus and outer lamellar zone of stroma of B. buteo; however; it was moderately stained in Eudocimus albus and weakly stained in the inner lamellar zone of stroma of B. buteo. The stroma of the three species was perforated at the anterior region with interfibrillar spaces. The endothelium layer possessed high affinity to PAS reaction in the three investigated species E. albus, A. platyrhynchus and B. buteo.

In the case of Anas platyrhynchus, Bowman's membrane showed a strong reaction to PAS stain, while Eudocimus albus appeared mildly stained and was absent in Buteo buteo (Fig. 2). Although the Descemet’s membrane (DM) showed an intense favorable PAS response in Anas platyrhynchus ' cornea, it was stained mildly in Buteo buteo (Fig. 2a).

3.3 SEM observations

There was great variation and high significance in the cell density between B. buteo with 4861.8 ± 322.7 cells per mm2 and 147.7 ± 20.4 cells per mm2 in A. platyrhyncus (Table 4). The epithelial cells of the investigated avian species were mostly regular polygonal cells in A. platyrhyncus and hexagonal in B. buteo with elevated cell borders, the surface of which was covered with densely packed microvilli and central nuclei projecting from the cell membrane of B. buteo (Fig. 3).

SEM micrograph of the corneal epithelial cells in a Anas platyrhuncus, b Buteo buteo showing: hexagonal cells (HX); regular polygonal cells (RPC) and Central Nuclei (CN) (Scale bar, 50 µm). The intercept showing higher magnification of SEM micrograph of a Anas platyrhuncus, b Buteo buteo. Note: Microvilli (Mv) and Cell Borders (CB)

Perforated corneal surface of the examined avian species appeared as cell breaks with different diameters (0.63 ± 0.13 µm) and high significant relationship in E. albus, and as coral sea with various diameters (4.0 ± 0.8 µm) in A. platyrhyncus; however, B. Buteo had less density of microholes with a width (1.0387 ± 0.15 µm) smaller than the other two investigated species. Microvilli were densely packed around microholes and were distinguished into elongated microvilli in B. buteo and shorted ones in E. albus (Figs. 4 and 5 and Table.4). Cilia were diffused over the surface of E. albus and A. platyrhyncus (Fig. 5). Little number of blebs with different diameters 13.0 ± 3.8 µm and microridges were spread over the epithelial cells of A. platyrhyncus (Fig. 6).

4 Discussion

The inspected species of birds represent a normal type of cornea, which is composed of five morphological layers; highly squamous epithelium, foremost and anterior basement film bowman's film, lamellated stroma with mucopolysaccharides ground lattice, posterior basement membrane Descemet’s membrane, and lastly a single row of endothelium. Comparable architecture was seen in numerous fowls and in different vertebrates [24, 25].

Concerning avian corneal epithelium of the studied species, it is arranged as a stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium, a basal columnar cell, followed by polyhedral layers, ranging from two to three, and ending with one layer of flat squamous cells. It is noticed that the characteristic feature of the stratified epithelium declined in the examined epithelial layer from E. albus (forested habitat) to B. Buteo (higher temperature desert area). One explanation for this decrease in the stratification of epithelium layer is accommodation with various habitats, which in turn stimulate the structural modifications in the epithelial layers [26].

As for the epithelium of forested species ibis (Eudocium albus), it acts as excellent protective cover for the rest optical layers due to its highly regenerative capacity during regenerations phases [27]. Similar explanations were reported in diurnal birds such as Circaetus gallicus [28] and Bubo bubo [29]. Furthermore, [30] traced the visual acuity in birds to the large cranial volume. These findings are confirmed in the present study in E. albus, as well as in other domestic ibis [31]

Magnification of the stratification traits in the epithelial layer of B. buteo can be traced to the reduction of light scattering and corneal opacity, besides the improvement of corneal transparency. Therefore, the epithelium of birds of B. buteo that inhabit high temperature desert areas represented highly refractive power lens for enhancement of its visual acuity and formation of sharp retinal image. These findings are in agreement with that observed in other predators [32, 33]

The recorded high variability in the stratified epithelium layer provides a protective layer against sever terrestrial surrounding habitats. Comparability of these observations are recorded in pensions and albatross [30, 34]. The present data are in disagreement with the findings of other studies conducted on other avian species and the Redtail Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) [35,36,37].

Epithelium constitutes an effective power lens in the aquatic habitat, and a protective shield in the terrestrial habitat. Like many diver birds which have water accommodation range that enables them to control the corneal curvature and change it according to the surrounding habitats [28]. The greater curvature, high refractive power and increasing intensity of light enable them to overcome the variety of refractive indices of the aquatic optical system [28].

Regarding classic H & E investigations, the second layer of stroma illustrats the normal distribution of collagen lamellae. In case of E. albus and A.platyrhuncus, the collagen fibrils in their stroma condense as only one lamellar zone and have relatively small interfibrillar spaces. Such structure is considered the basic resistance to intraocular pressure, bears the tensile forces of the external environmental conditions, and protects intraocular tissues from trauma [38]. Similar findings are reached in Gallus gallus [39], and some vertebrates [40, 41].

Concerning Buteo buteo stroma, the present data distinguished it into two main bulks; loosed inner and compacted outer lamellar zones. The outer zone is perforated anteriorly by mostly circular interfibrillar space like a large entrance for the light beam that allows increasing the intensity of the light required for sharp retinal image and enhancement of the corneal transparency. Harsh habitats of these predators and their necessities for accurate vision to catch up their prey stimulate its morphological ultrastructure to adapt with their ecological surroundings [30].

As a result of these modifications, the collagen lamellae enables cornea to rotate their globes in a stable way and provides a clear protective goggle [42]. Previous studies, e.g. Boyce, Jones [43] and Neagu and Petraru [28], have revealed that the preying mechanism is based on the vision properties and the anatomical structure of eyes of both predators and preys. Whereas the predators possessed large eyes with more curved cornea, the preys have laterally small eyes and flattened cornea.

[38] proposed that the compacted lamellae of the stroma have a tendency to corneal opacity and cloudy properties, due to the low intensity of light passing through the narrow interfibrillar spaces which results in not frequently formation of sharp retinal image. Similar observations are made in the present study, whereas the corneal transparency of B. buteo is higher than that of the other two studied species, and are in agreement with the findings in Peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) and Redtail Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) [37].

Accessory of the stromal layers of the three investigated species is formed from the polysaccharides ground matrix and proteoglycans producers (Keratocytes). They are distributed with moderate density in the two studied species E. albus and A. platyrhncus. Despite being extensively dispersed in the stroma of B. buteo especially, the anterior portion of the outer lamellar zone is aligned along its collagen lamellae. These observations are in agreement with Tsukahara, Tani [39] and Akhtar, Khan [44] in various species of domestic birds. Moreover, these observations illustrate the integrated function of the keratocytes as an enhancer for corneal transparency. Both Inoue, Watanabe [45] and Meek and Knupp [38] indicated that the light intensity strongly correlated with intensity of collagen in the stroma and stromal thickness in birds requiring high visual acuity and also in a number of proteoglycans. Therefore, keratocytes form more than 15% of corneal transparency [46,47,48].

The present histological demonstrations revealed the presence of two basal lamina (bowman's and Descemet’s membranes) in A. platyrhunicus and E. albus, limiting the two cellular layers epithelium and endothelium. In spite of their absence in the case of B. buteo cornea, they are well developed and identified in domestic birds, e.g. pigeon,penguins and albatross (aquatic aves) [28].

Generally, in various vertebrate groups, Bowman's and Descemet’s membranes contribute morphologically with less than 4% to the total corneal thickness and functionally with less than 30% to the corneal transparency [49]. Both of the two limiting membranes appeared in continuous state without any detectable interpretations or abnormalities in the investigated cornea [50]. Their homogenous elastic fibers are correlated to their cellular layers such as Struthio camelus and Dromaius novaehollandiae [51].

Bowman's membranes not only protect the inertocular layers from the harmful UV radiations, but also they protect producers of ground matrix of the stromal layers [44]. Recently, many authors reported that both bowman's and endothelium have high absorption coefficient compared to that of the stromal layer, which exceeds 30% of the total percent of absorption [52]. These could be due to the especially molecular composition and absorption coefficient of bowman's membrane and the elevated ratio of ascorbic acid content of epithelium layer, both of them acted as effective filter to protect the ocular tissue from harmful UV- radiation [44, 53].

However, absorption coefficient of stromal layer referred to the higher thickness and large polysaccharide content in their extra cellular matrix, besides microstructural organization of collagen fibers in Eolophus roseicapillus [54] and Bubo strix [55]. In case of absence of bowman’s membrane from corneal ultrastructure, as in B. buteo, stromal collagen fibrils are affirmably packed and are characterized by thin diameter to act as effective filter for absorption of the excessive UV spectra.

Generally, posterior basement membrane (Desecmet’s membrane) is considered a secretory product of endothelium layers during pre and postnatal stages as it is thickening with age. Chen, Li [56] reported that Desecmet’s membrane is constituted from different sorts of collagen fibrils and organized glycoprotein. They added that such posterior basement membrane is responsible for preserving the phenotypic and morphometric features of endothelium, besides maintaining the endothelium function under normal physiological conditions. Furthermore, Desecmet’s membrane provides anchoring to the posterior corneal surface during its morphogenesis process through acting as a stable scaffold (Chen et al. 2017). Akhtar, Khan [44] proposed that the thickness of Desecmet’s membrane does not exceed 0.5% of the total thickness, in spite of its vital role in preserving arid surrounding conditions on the stromal layer to prevent the corneal opacity. Moreover, this membrane has a regenerator property for the endothelium layer under mechanical scraping or wounding this layer in different animals [56].

The present study documented regular arrangement of the endothelium layer as single row of flat squamous cells at the separating boundary between corneal stroma and aqueous humor of the anterior chamber in the three studied species. Relatively, the same arrangement was assumed in penguin (Spheniscus magellanicus), Gallus gallus and Struthio camelus [55].

Pigatto, Laus [55] suggested that the endothelium layer is considered as a generator for most corneal tasks, such as declining stromal hydration, preserving corneal thickness, and improvement of corneal transparency. In addition to the small thickness of the endothelial layer in most vertebrates, especially birds, that does not exceed 5% of the total thickness, it works as very active pump of inflow water from aqueous humor and stromal matrix.

Moreover, thickness of corneal layers of the examined avian species recorded very high statistical significant variance (P < 0.000), where B. buteo (predators investigated species) demonstrated the higher thickness of the epithelial, stroma and endothelium layers, compared to the other two investigated species. Saadi-Brenkia, Hanniche [41] illustrated that higher thickness of stromal lamellae and corneal layers improve the corneal transparency and increase the corneal curvature. Such adaptations, according to the authors, are due to their functional transparency for the high temperature in arid habitat to catch preys.

A sharp retinal image stimulating excellent visual acuity, that is required for predator birds, can result from an enhanced corneal transparency and enlargement of light entrance. This can be achieved through increasing the thickness of corneal epithelium, protective google of the cornea and minimal stratification character [57]. Previous data demonstrated similar findings in Redtail Hawk Buteo jamaicensis and Peregrine falcon Falco peregrinus [37]. Additionally, high stromal thickness may be traced to large interfibrillar spaces between collagen lamellae, whereas it is responsible for increasing the quantity of incoming light and, therefore, declining the corneal opacity and light scattering that result from alteration of refractive indices of various visual habitats, as in falcons [37, 58].

Interestingly, species of intermediated habitat (amphibious vision), such as A. platyrhunces, possess relatively thinner stroma than the other two studied species. This can be traced to the high variability of their inhabiting conditions and their refractive indices of different optical medium. For these reasons, the thinner stroma has great impact on adaptation in various optical systems, which in turn increases corneal curvature and improves corneal transparency, as in albatross and penguin which are characterized by emmetropic cornea in air and water [59, 60].

Higher thickness of corneal endothelium maintains the phenotypic morphological composition and declines stromal hydration, as confirmed in various studies of pigeon and other species of birds [4].

Considering applying PAS stain on avian cornea, glycogen content is distributed relative to the biological requirements of the corneal layers for accommodation with different terrestrial, either forested or arid, habitat. The superficial corneal layer (epithelium) is loaded with variable degrees of PAS stain among the examined species; where it is strongly stained in E. albus; moderately stained in B. buteo, and weakly stained in A. platyrhunces. High glycogen content could be traced to the high metabolic activity and aerobic glycolysis of epithelial layer that result from biochemical reaction and oxygen consumption in different ecological conditions. These findings are similar to that documented in chick and domestic pigeon by Albuquerque, Pigatto [61].

The present study demonstrated these results in E. albus and its biological requirements to elevate the ratio of polysaccharides content and ensure its oxygen consumptions in case of the hydration state of stromal layer [8]. Previous studies reached similar findings in Gallus gallus domesticus and widespread species of birds [55].

The highly stained PAS cornea in the studied epithelial layer could be traced to the high absorption coefficient of UV- radiation. Exposure to UV radiation stimulates increasing the concentration of glycogen and glucose in the concerned tissue [26].

Moreover, moderated stained epithelium in B. Buteo revealed a high level of glycogen as a result of exposure to excess of UV spectra in their arid environment. Subsequently, low affinity of PAS reaction in the epithelium of A. platyrhunces came in agreement with the findings of previous researches conduced on sea otter, penguin and some species of falcons [4, 26, 28, 37].

The examined stroma of the three studied species recorded a strong affinity to PAS reaction in the outer lamellar zone of B. buteo and A. platyrhunces, but was weakly stained in E. albus. This may be due to the metabolic activity of the two examined species B. buteo and A. platyrhunce than E. albus, because of their body weight. The latter species raise their metabolic glycolysis and also their glycogen content as previously recorded in falcons and domestic pigeon [41]. In addition, B. buteo is characterized by higher daily activity, including catching preys and travelling long distances with high speed [30]. Therefore, their metabolic activity is higher and their glycogen composition is more elevated than other E. albus species.

The endothelium layer was recognized in the three studied species with strong affinity of PAS stain. This could be due to its cellular activity and higher oxygen consumptions that in turn stimulate concentration of polysaccharides [8]. Additionally, bowman’s and Descemet’s membrane showed high polysaccharides content in A. platyrhunces with amphibious visual characters. The absorption coefficient of UV radiation of these basement membranes is mailnly responsible for increasing glycogen composition. These cellular layers preserve the corneal stiffness and resist any tensile forces in most amniotes [62].

The investigated avian epithelial cell density showed very high statistically significant variations (P < 0.000), where great significance between B. buteo and A. platyrhunces is observed. Obviously, there is sharp decreasing in epithelial cell density in A. platyrhunces which may be due to absence of the role of corneal adaptation and activated lenticular accommodation. In case of submerged eye, such as that of A. platyrhunces in our investigation and that of cormorants [59], it is suggested that the lens is stimulated as an accommodative agent to adjust proper retinal image and compensate for the corneal transparency loss that results from similarity of refractive indices in aqueous humor and water.

Another critical point concerned the high epithelial cell density of B. buteo which could be due to its critical requirements for sharp retinal image and high visual acuity. Therefore, they are characterized by emmetropic eye in the terrestrial habitat and hyperopic in air to adapt to travelling large distances with high speeds and enhancement of its catching preys capacity. Relative significance of the cell density in epithelial layers was demonstrated in Chicken (Gallus gallus), Redtail Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) and Peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) [37]. On the contrary, the flattened corneal species suffer from relative loss of corneal transparency during submerging and equality of refractive indices in cornea and water. Subsequently, the adaptive structural modification of their optical system stimulated their lenticular accommodation, whereas the optical lens compensated the corneal transparency loss. Such findings are equally suggested in penguins, albatrosses and seals [59].

Organizations of surface epithelial cells of avian corneal surface are characterized by highly regular polygonal epithelial cells in A. platyrhunces and sharp hexagonal cells with elevated borders and concentric notable nucleus in B. buteo. The high regularity of epithelial cells protects from the hydration status of the stromal layer, and ensures declining wet table epithelium and hydrated stroma [21, 63]. Some species of aves, like Phoenicopterus chilensis, Eolophus roseicapillus, Australian galah and Struthio camelus, exhibit the same regularity of polygonal cells mixed with hexagonal cells [10, 64]

The corneal surface microprojections, like microvilli, are elongated in B. buteo and shorted in A. platyrhunces. Microvilli contribute to 50% of the corneal transparency and are necessary for stabilization of tear film via adsorption of more mucin. This role coats and protects against infections from the surrounding habitat, as in the case of Dromaius novaehollandiae and Eudyptala [21]. Partially, sea otter and Penguins, as aquatic species, exhibited the same shorted microvilli that support nutritional exchanges [65].

The spreading of microholes over their corneal surface showed a high statistical significance in A. platyrhunces among the examined species. Dispersion of microholes over the corneal surface of the investigated species of birds is responsible for lubrication of the outer corneal surface and reducing the friction resistance that results from rapid movement of ocular adnexa [66].

Diffusion of cilia structure over the corneal surface of E. albus isolated the morphological features of epithelial cells and packed densely over the surface. Primary cilium represented microtubules that arise from inside organelle and protrude outside of plasma membrane and are responsible for morphogenesis and organization of corneal epithelial. On the other hand, cilia were represented rarely over the corneal surface of A. platyrhaunces. Surprisingly, the packing of cilia over corneal surface strongly correlated with increasing the cell density and enhancement of corneal transparency, according to Grisanti, Revenkova [67].

5 Conclusions

The present study gives a brief account of some structures of cornea for three Avian’s species in Egypt and elaborated on the role of some functional anatomical structures throughout the vision. The data take into account the environmental circumstances of the three species’ surroundings which are reflected on the distribution of microprojections over the corneal surface, such as cilium in ibis (Ediusmus albus) which covered the whole cornea. Furthermore, the study offers a big number of cornea structure photomicrographs, compared and integrated with the reviewed published outcomes. In addition, the present data concentrate on the unique organizational stromal lamellae of the birds of prey, such as the hawk (Buteo buteo), which assisted in flight, hunting and other biological process. The evolutionary variations in avian cornea from various existing species have showed different distribution of microprojections over the corneal surface.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Change history

19 January 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43088-021-00180-1

Abbreviations

- EP:

-

Epithelium

- S:

-

Stroma

- DM:

-

Descemet’s membrane

- EN:

-

Endothelium

- K:

-

Keratocytes

- Sq:

-

Squamous cells

- Py:

-

Polyhedral cells

- Bc:

-

Basal columnar cells

- B:

-

Bowman’s membrane

- OLZ:

-

Outer Lamellar Zone of Stroma

- ILZ:

-

Inner Lamellar Zone of Stroma

- IS:

-

Interfibiller Space

- HX:

-

Hexagonal Cells

- RPC:

-

Regular Polygonal Cells

- CN:

-

Central Nuclei

- Mv:

-

Microvilli

- CB:

-

Cell Borders

- MH:

-

Microholes

- Ci:

-

Cilia

- MR:

-

Microridges

- Bb:

-

Blebs

References

Schmitz L, Wainwright PC (2011) Nocturnality constrains morphological and functional diversity in the eyes of reef fishes. J BMC Evol Biol 11(1):338. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-11-338

Jonasova K, Kozmik Z (2008) Eye evolution: lens and cornea as an upgrade of animal visual system. Paper presented at the seminars in cell and developmental biology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.10.005

Land MF, Nilsson D-E (2012) Animal eyes. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Tamayo-Arango LJ, Baraldi-Artoni SM, Laus JL, Vicenti FAM, Pigatto JA, Abib FC (2009) Ultrastructural morphology and morphometry of the normal corneal endothelium of adult crossbred pig. J Ciência Rural 39(1):117–122

Clark JI (2004) Order and disorder in the transparent media of the eye. Exp Eye Res 78(3):427–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2003.10.008

Meek K (2008) The cornea and sclera Collagen. Springer, pp 359–396

Leonard D, Meek K (1997) Refractive indices of the collagen fibrils and extrafibrillar material of the corneal stroma. J Biophys J 72(3):1382–1387. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78784-8

Kinoshita JH (1962) Some aspects of the carbohydrate metabolism of the cornea. J Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1(2):178–186

Peng H, Katsnelson J, Yang W, Brown MA, Lavker RM (2013) FIH-1/c-kit signaling: a novel contributor to corneal epithelial glycogen metabolism. J Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54(4):2781–2786. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.12-11512

Collin SP, Collin HB (2000) A comparative SEM study of the vertebrate corneal epithelium. Cornea 19(2):218–230. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003226-200003000-00017

El Bakry AM (2014) Comparative study of the structural features of the corneal epithelium in some vertebrates. J Egypt J Zool 174(1661):1–32. https://doi.org/10.12816/0009341

Goodman SM, Meininger PL (1989) The birds of Egypt. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Eason P, Rabia B, Attum O (2016) Hunting of migratory birds in North Sinai, Egypt. Bird Conserv Int 26(1):39–51. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270915000180

Wilson AC, Ashton PD, Calevro F, Charles H, Colella S, Febvay G, Jander G, Kushlan PF et al (2010) Genomic insight into the amino acid relations of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum, with its symbiotic bacterium Buchnera aphidicola. J Insect Mol Biol 19:249–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00942.x

Dunning J Jr (1993) CRC handbook of avian body masses. CRC Press, Ann Arbor

Suvarna S, Layton C (2013) Bancroft's theory and practice of histological techniques. Churchill Livingstone. J Elsevier. Aughey E, Frye FL. Comparative veterinary histology. Manson publishing, 21(2010), 173–186

Passo RM, Hoskins ZB, Tran KD, Patzer C, Edmunds B, Morrison JC, Parikh M, Takusagawa HL et al (2019) Electron beam irradiated corneal versus gamma-irradiated scleral patch graft erosion rates in glaucoma drainage device surgery. Ophthalmol Ther. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-019-0190-x

McManus J (1946) Histological demonstration of mucin after periodic acid. Nature 158(4006):202. https://doi.org/10.1038/158202a0

Bancroft J, Layton C, Bancroft J (2013) The hematoxylin and eosin, connective and mesenchymal tissues with their stains, 7th edn. Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia

Jeffree CE, Read ND (1991) Ambient-and low-temperature scanning electron microscopy. J Electron Microsc Plant Cells 313:413

Goldstein JI, Newbury DE, Michael JR, Ritchie NW, Scott JHJ, Joy DC (2017) Scanning electron microscopy and X-ray microanalysis. Springer, Berlin

Abràmoff MD, Magalhães PJ, Ram S (2004) Image processing with ImageJ. Biophoton Int 11(7):36–42

Last JA, Thomasy SM, Croasdale CR, Russell P, Murphy CJ (2012) Compliance profile of the human cornea as measured by atomic force microscopy. J Micron 43(12):1293–1298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micron.2012.02.014

Nalbach H-O (1993) Exploring the image. In: Vision, brain, behavior in birds, pp 25–46

Vidal M, Segovia Y, Victory N, Navarro-Sempere A, García M (2018) Light microscopy study of the retina of the Yellow-legged Gull, Larus michahellis, and the relationship between environment and behaviour. J Avian Biol Res 11(4):231–237. https://doi.org/10.3184/175815618X15282819619105

Swamynathan SK, Crawford MA, Robison WG Jr, Kanungo J, Piatigorsky J (2003) Adaptive differences in the structure and macromolecular compositions of the air and water corneas of the “four-eyed” fish (Anableps anableps). J Exp Eye Res 17(14):1996–2005. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.03-0122com

Svaldenienė E, Paunksnienė M, Babrauskienė V (2003) Appliance of digital ultrasonic technique in canine cornea investigations. Ultrasound 46(1):41–45

Neagu A, Petraru O (2015) Aquatic” vs. “terrestrial” eye design. A functional ecomorphological aproach. J Analele Stiinţifice ale Universitaţii, Alexandru Ioan Cuza” din Iasi, s. Biologie animal 61:101–115

Kiama SG, Maina J, Bhattacharjee J, Weyrauch K (2001) Functional morphology of the pecten oculi in the nocturnal spotted eagle owl (Bubo bubo africanus), and the diurnal black kite (Milvus migrans) and domestic fowl (Gallus gallus var. domesticus): a comparative study. J Zool 254(4):521–528. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0952836901001029

Jones MP, Pierce KE Jr, Ward D (2007) Avian vision: a review of form and function with special consideration to birds of prey. J Exotic Pet Med 16(2):69–87. https://doi.org/10.1053/J.JEPM.03.012

Foster JW, Jones RR, Bippes CA, Gouveia RM, Connon CJ (2014) Differential nuclear expression of Yap in basal epithelial cells across the cornea and substrates of differing stiffness. Exp Eye Res 127:37–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2014.06.020

Banks MS, Sprague WW, Schmoll J, Parnell JA, Love GD (2015) Why do animal eyes have pupils of different shapes? Sci Adv 1(7):e1500391. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1500391

Zhou B, Sit AJ, Zhang X (2017) Noninvasive measurement of wave speed of porcine cornea in ex vivo porcine eyes for various intraocular pressures. Ultrasonics 81:86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultras.2017.06.008

Borkar DS, Gonzales JA, Tham VM, Esterberg E, Vinoya AC, Parker JV, Uchida A, Acharya NR (2014) Association between atopy and herpetic eye disease: results from the pacific ocular inflammation study. JAMA Ophthalmol 132(3):326–331. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.6277

Gibson MA, Hatzinikolas G, Davis EC, Baker E, Sutherland GR, Mecham RP (1995) Bovine latent transforming growth factor beta 1-binding protein 2: molecular cloning, identification of tissue isoforms, and immunolocalization to elastin-associated microfibrils. Mol Cell Biol 15(12):6932–6942. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.15.12.6932

El-Bakry AM (2011) Comparative study of the corneal epithelium in some reptiles inhabiting different environments. Acta Zoologica 92(1):54–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6395.2009.00444.x

Winkler M, Shoa G, Tran ST, Xie Y, Thomasy S, Raghunathan VK, Murphy C, Brown DJ et al (2015) A comparative study of vertebrate corneal structure: the evolution of a refractive lens. J Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci 56(4):2764–2772. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.15-16584

Meek KM, Knupp C (2015) Corneal structure and transparency. J Prog Retinal Eye Res 49:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.07.001

Tsukahara N, Tani Y, Lee E, Kikuchi H, Endoh K, Ichikawa M, Sugita S (2010) Microstructure characteristics of the cornea in birds and mammals. J Vet Med Sci 72(9):1137–1143. https://doi.org/10.1292/jvms.09-0470

Scott J, Bosworth T (1990) The comparative chemical morphology of the mammalian cornea. J Basic Appl Histochem 34(1):35–42

Saadi-Brenkia O, Hanniche N, Lounis S (2018) Microscopic anatomy of ocular globe in diurnal desert rodent Psammomys obesus (Cretzschmar, 1828). J Basic Appl Zool 79(1):43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41936-018-0056-0

Collin SP, Collin HB (2001) The fish cornea: adaptations for different aquatic environments. Sensory biology of jawed fishes: new insights, 57

Boyce B, Jones R, Nguyen T, Grazier J (2007) Stress-controlled viscoelastic tensile response of bovine cornea. J Biomech 40(11):2367–2376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.12.001

Akhtar S, Khan AA, Albuhayzah HA, Almubrad TM (2017) Cornea and its adaptation to environment and accommodation function in veiled chameleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus): ultrastructure and 3D transmission electron tomography. Microsc Res Tech 80(6):578–589. https://doi.org/10.1002/jemt.22833

Inoue T, Watanabe H, Yamamoto S, Maeda N, Inoue Y, Shimomura Y, Tano Y (2002) Recurrence of corneal dystrophy resulting from an R124H Big-h3 mutation after phototherapeutic keratectomy. J Cornea 21(6):570–573. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ICO.0000016357.28672.D5

Jester JV (2008) Corneal crystallins and the development of cellular transparency. Paper presented at the Seminars in cell and developmental biology, vol 19(2), pp 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.09.015

Hassell JR, Birk DE (2010) The molecular basis of corneal transparency. J Exp Eye Res 91(3):326–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2010.06.021

Torricelli AA, Bechara SJ, Wilson SE (2014) Screening of refractive surgery candidates for LASIK and PRK. Cornea 33(10):1051–1055. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000000171

Reinstein DZ, Gobbe M, Archer TJ, Silverman RH, Coleman DJ (2008) Epithelial thickness in the normal cornea: three-dimensional display with Artemis very high-frequency digital ultrasound. J Refract Surg 24(6):571–581. https://doi.org/10.3928/1081597X-20080601-05

El-Dawi E (2005) Comparative studies on the corneal structural adaptation of two rodents inhabiting different environments. Egypt J Hosp Med 20:131–147

Hayashi S, Osawa T, Tohyama K (2002) Comparative observations on corneas, with special reference to Bowman’s layer and Descemet’s membrane in mammals and amphibians. J Morphol 254(3):247–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.10030

Doutch JJ, Quantock AJ, Joyce NC, Meek KM (2012) Ultraviolet light transmission through the human corneal stroma is reduced in the periphery. Biophys J 102(6):1258–1264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2012.02.023

Massoudi D, Malecaze F, Galiacy SD (2016) Collagens and proteoglycans of the cornea: importance in transparency and visual disorders. J Cell Tissue Res 363(2):337–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-015-2233-5

Kolozsvári L, Nógrádi A, Hopp B, Bor Z (2002) UV absorbance of the human cornea in the 240-to 400-nm range. J Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43(7):2165–2168

Pigatto JA, Laus JL, Santos JM, Cerva C, Cunha LS, Ruoppolo V, Barros PS (2005) Corneal endothelium of the magellanic penguin (Spheniscus magellanicus) by scanning electron microscopy. J Zoo Wildl Med 36(4):702–706. https://doi.org/10.1638/05017.1

Chen J, Li Z, Zhang L, Ou S, Wang Y, He X, Zou D, Jia C et al (2017) Descemet’s membrane supports corneal endothelial cell regeneration in rabbits. Sci Rep 7(1):6983. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07557-2

Gendron SP, Rochette PJ (2015) Modifications in stromal extracellular matrix of aged corneas can be induced by ultraviolet A irradiation. Aging Cell 14(3):433–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.12324

Jester JV, Winkler M, Jester BE, Nien C, Chai D, Brown DJ (2010) Evaluating corneal collagen organization using high resolution non linear optical (NLO) macroscopy. J Eye Contact Lens 36(5):260. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICL.0b013e3181ee8992

Katzir G, Howland HC (2003) Corneal power and underwater accommodation in great cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis). J Exp Biol 206(5):833–841. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.00142

Mass AM, Supin AY (2007) Adaptive features of aquatic mammals’ eye. Anat Rec Adva Integr Anat Evol Biol 290(6):701–715. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.20529

Albuquerque L, Pigatto JAT, Freitas LVDRP (2015) Analysis of the corneal endothelium in eyes of chickens using contact specular microscopy. Semina Ciências Agrárias 36(6Supl2):4199–4206. https://doi.org/10.5433/1679-0359.2015v36n6Supl2p4199

Yang W, Meyers MA, Ritchie RO (2019) Structural architectures with toughening mechanisms in Nature: a review of the materials science of Type-I collagenous materials. J Prog Mater Sci 103:425–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2019.01.002

Osman IM, Madwar AY (2016) Scanning electron microscopy of human corneal lenticules at variable corneal depths in small incision lenticule extraction cases. J Delta J Ophthalmol 17(3):109. https://doi.org/10.4103/1110-9173.195261

El-Bakry AM (2011) Comparative study of the corneal epithelium in some reptiles inhabiting different environments. J Acta Zoologica 92(1):54–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6395.2009.00444.x

Jindal R, Sinha R (2019) Malachite Green Induced Ultrastructural Corneal Lesions in Cyprinus carpio and Its Amelioration Using Emblica officinalis. J Bull Environ Contamin Toxicol 102(3):377–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-019-02549-6

Collin SP, Collin HB (2006) The corneal epithelial surface in the eyes of vertebrates: environmental and evolutionary influences on structure and function. J Morphol 267(3):273–291. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.10400

Grisanti L, Revenkova E, Gordon RE, Iomini C (2016) Primary cilia maintain corneal epithelial homeostasis by regulation of the Notch signaling pathway. Development 143(12):2160–2171. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.132704

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research not received specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZA: Interpretation of laboratory results and statistical analysis of data, and drafting of manuscript. ARG: was involved in data curation and analysis. REA: Participated in the design of the study, writing, reviewing. AME: was involved in conceptualized, reviewing, editing, designed the methodology, and prepared the original draft of manuscript. The authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the standards set in the guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Zoology Department in the Faculty of Science at Beni-Suef University (under an Approval Number is BSU/FS/2015/9.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised to correctly present the second author's name

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdelftah, Z., Gaber, A.R., Abo-Eleneen, R.E. et al. Microstructure characteristics of cornea of some birds: a comparative study. Beni-Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci 10, 66 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43088-021-00155-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43088-021-00155-2