Abstract

Background

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is a significant complication among cirrhotic patients with ascites and is associated with high mortality. Early diagnosis and treatment of SBP are crucial, as they are associated with better outcomes and lower mortality. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and mean platelet volume (MPV) are routine, inexpensive, easily measured markers readily obtained from a complete blood count (CBC). Several studies have addressed the diagnostic role of NLR and MPV in patients with SBP but with different cutoff values, sensitivity, and specificity. Therefore, we conducted this study to validate the clinical utility of NLR and MPV in diagnosing SBP.

Methods

This study included 332 cirrhotic patients with ascites who were admitted to Sohag University Hospitals in Egypt between April 2020 and April 2022. Of these patients, 117 had SBP, and 215 did not. Both NLR and MPV were measured in all patients, and the ability of NLR and MPV to diagnose SBP was assessed using the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

Results

NLR and MPV were significantly elevated in patients with SBP compared to those without SBP (P < 0.001). At a cutoff value of 5.6, the sensitivity and specificity of the NLR in detecting SBP were 78% and 81%, respectively. In contrast, MPV, at a cutoff value of 8.8 fL, had a sensitivity of 62% and a specificity of 63%. The combination of NLR and MPV did not provide significant additional diagnostic value beyond only using NLR.

Conclusion

Although NLR and MPV allow the detection of SBP, the NLR has higher clinical utility and is superior to MPV in diagnosing SBP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is a severe complication among cirrhotic patients with ascites and is defined as an infection in the ascitic fluid without a clear source in the abdomen. It is the most common infection in hospitalized cirrhotic patients, with a 20–30% mortality rate and comprising about 10–30% of all bacterial infections [1]. The clinical presentation of SBP is variable; for example, fever or leukocytosis might be absent, and about a third of the patients might be asymptomatic. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is necessary for early diagnosis, which is established when the polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMNL) count in ascitic fluid exceeds 250 cells/μl [2,3,4].

Delayed diagnosis of SBP is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. The diagnosis of SBP requires an invasive procedure, and the differential cell count is commonly performed manually using light microscopy and counting chambers. This method is subjective and time-consuming, and PMNL lysis during transfer to the laboratory may lead to false-negative results [5, 6]. Therefore, it is essential to develop rapid, reliable, and non-invasive techniques for diagnosing SBP [7].

The blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a simple and inexpensive biomarker that reflects the balance of the immune and inflammatory systems and the response to systemic inflammation [8]. NLR is an indicator of subclinical inflammation. Increased neutrophil and decreased lymphocyte numbers in the peripheral blood may indicate the early stages of a severe infection. Several studies have demonstrated the clinical utility of NLR as a marker for bacterial infection [9].

Mean platelet volume (MPV) is an inexpensive and easily accessible laboratory marker that reflects platelet function and activation. Intriguingly, MPV has been considered an inflammatory marker [10]. Several studies have found a relationship between MPV and proinflammatory conditions, particularly acute infections and chronic viral hepatitis [11,12,13].

Previous research has shown that NLR [9, 14, 15] and MPV levels [15,16,17] are elevated in cirrhotic individuals with SBP. However, these studies had different cutoff values and reported varying specificity, sensitivity, and predictive values. Therefore, this study aimed to validate the clinical utility of NLR and MPV as diagnostic markers for SBP.

Patients and methods

Patients

This observational cross-sectional study was performed in the Tropical Medicine and Gastroenterology Department, Sohag University Hospitals, Sohag, Egypt, between April 2020 and April 2022. The study protocol was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee (MREC) of the Sohag Faculty of Medicine (IRB number: Soh-Med-21-02-22) and ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT04775420). All participants or their family members (for patients who were unconscious) provided informed written consent before enrolling in the study.

A total of 332 cirrhotic patients with ascites (223 males and 109 females) were included in the study, 117 (35.2%) of whom had SBP, and 215 (64.8%) of whom did not have SBP. The diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was based on clinical data and findings from abdominal ultrasound. The existence of at least 250 cells/ml of PMNLs in the ascitic fluid, with or without a positive ascitic fluid culture, in the absence of secondary peritonitis and hemorrhagic ascites, was used to establish the diagnosis of SBP [4].

We excluded patients with immunosuppression, heart failure, clinically and laboratory-evident autoimmune diseases, hematological disorders, peripheral vascular disease, severe infections other than SBP, antibiotic treatment before hospitalization, and patients on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), anticoagulants, or oral contraceptives.

Methods

All patients underwent a detailed medical history, clinical examination, abdominal ultrasonography, and laboratory investigations. Medical history included information about age, gender, drug or alcohol intake, fever, abdominal pain, jaundice, bleeding tendency, swelling of legs or abdomen, changes in neuropsychiatric status, and vomiting of blood or passage of melena. During the clinical examination, vital signs, the grade of hepatic encephalopathy using the West Haven criteria, the grade of ascites, and the presence of purpura or ecchymosis were recorded.

Ten milliliters of blood were taken from patients at admission and then centrifuged. The serum was examined for the following: A complete blood count (CBC) was performed, from which the white blood cell (WBC) count, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and MPV levels were recorded. Additional tests included serum creatinine, liver function tests, sodium, and viral hepatitis markers (hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis C antibody). Ten milliliters of ascitic fluid were obtained by paracentesis performed under sterile conditions, guided by abdominal ultrasonography with the patient lying supine, to establish the diagnosis of SBP. Total ascitic fluid proteins, white blood cells (WBCs), and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNLs) were determined.

The Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) [18] and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores [19] were calculated to assess liver disease severity. The NLR was calculated by dividing the neutrophil number by the number of lymphocytes obtained from the CBC.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM-SPSS V18 (IBM-SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics: means, standard deviation (SD), median, frequency, and percentage were calculated. The normality of continuous variables was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Student’s t test analysis was used to compare the means of dichotomous parametric data. In contrast, the medians of non-parametric data were compared by the Mann-Whitney U/independent sample Kruskal-Wallis test. A chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare the differences in the distribution of frequencies among different groups. The efficacy of NLR and MPV for the diagnosis of SBP was demonstrated by the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve. A p value < 0.05 was statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the studied population

The studied patients’ baseline characteristics and laboratory parameters are demonstrated in Tables 1 and 2, and Supplementary Table 1. The mean age was 61.2 ± 11.3 years (range, 19–90), 67.2% were males, and HCV was our patients’ primary etiology of cirrhosis (80.4%). Patients with SBP were younger and had a more advanced liver disease than those without SBP. Moreover, they had a significantly higher prevalence of fever, abdominal pain, and jaundice. WBCs, PMNLs, NLRs, MPVs, and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were significantly elevated in patients with SBP, while blood lymphocytes were significantly lower. Other clinical and laboratory characteristics were comparable between patients’ subgroups.

ROC curve analysis of the diagnostic performance of NLR and MPV for the detection of SBP

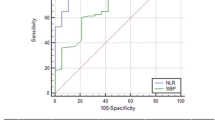

We found that at a cutoff level of 5.6, NLR had 78% sensitivity and 81% specificity for diagnosing SBP [AUC (95% CI); 0.872 (0.83–0.913)] with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 68%, a negative predictive value (NPV) of 87%, and overall accuracy of 80%. MPV at a cutoff level of 8.8 fL had a sensitivity of 62% and specificity of 63% [AUC (95% CI); 0.678 (0.616–0.74)], a PPV of 47%, an NPV of 75%, and overall accuracy of 62%. Using both NLR and MPV at a cutoff value of 14.5, a sensitivity of 79% and specificity of 81% [AUC (95% CI); 0.892 (0.854–0.931)] were obtained, with a PPV of 69%, NPV of 88%, and overall accuracy of 80% (Table 3, Fig. 1).

Discussion

Early diagnosis and treatment of SBP are crucial, as they are associated with better outcomes and lower mortality. However, the diagnosis is based on an elevated PMNL count in the ascitic fluid (> 250 cells/ml), which is an invasive, time-consuming, and operator-dependent method [20]. Therefore, developing a simple, rapid, inexpensive, reliable, and objective method for diagnosing SBP is crucial to improving outcomes [7].

Many tests have been investigated for the early diagnosis of SBP, and some have proved helpful, but their use is confined to research purposes or limited by the high cost. Examples include lactoferrin in ascitic fluid, pH testing, leukocyte esterase reagent strips, serum, ascitic fluid calprotectin, and procalcitonin [21]. NLR and MPV are routine, inexpensive, and easily measured markers readily obtained from CBC.

The main finding of the present study is that cirrhotic patients with SBP had significantly higher NLR and MPV levels than patients without SBP. Additionally, NLR had better overall accuracy for diagnosing SBP than MPV.

NLR reflects the dynamic interaction of adaptive (lymphocytes) and innate (neutrophils) immune function during disease and different pathological conditions. Several studies have demonstrated that NLR is a highly sensitive marker of inflammation, infection, and sepsis. Clinical trials revealed NLR’s significant predictive and prognostic efficacy and its role in the diagnosis and stratification of bacteremia, systemic infection, and sepsis [22, 23]. In the current study, patients with SBP had a substantially higher NLR than those without SBP (P < 0.001). Moreover, NLR detects SBP at a cutoff value of 5.6 with sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and overall accuracy of 78%, 81%, 68%, 87%, and 80%, respectively (AUC 0.872). The present results are consistent with the observations of many authors who have studied the diagnostic power of NLR in SBP patients [9, 15, 24,25,26,27]. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis concluded that NLR is a reliable marker that can be readily used in diagnosing SBP among cirrhotic patients [14]. However, Badawi et al. [28] found no significant association between NLR and SBP. The cutoff value of NLR in the present study (5.25) is comparable to that reported by Abdel Hammed et al. [26], but higher than that was observed in previous studies (the cutoff values ranged from 2.5 to 3.96) [9, 15, 24, 25, 27], with comparable AUC, sensitivity, and specificity.

MPV is an indicator of platelet activation. Large platelets are more metabolically and enzymatically active than small platelets. Moreover, besides their hemostatic function, they are involved in inflammation by releasing chemokines and activating and recruiting neutrophils to sites of injury and infection [29]. In this study, patients with SBP had significantly higher MPV levels than those without SBP (P < 0.001). Moreover, MPV detects SBP at a cutoff value of 8.8 fL with sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and overall accuracy of 62%, 63%, 47%, 75%, and 62%, respectively (AUC: 0.678). The cutoff value of MPV in the current study (8.8 fL vs. 8.3–8.9 fL) is close to that reported in previous studies [15,16,17, 21, 26, 30], despite lower AUC, sensitivity, and specificity.

We noticed that diagnostic performance was not improved when combining NLR and MPV. At a cutoff value of 14.5, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and overall accuracy of this combination were 79%, 81%, 69%, 88%, and 80%, respectively (AUC 0.892). These values are close to those reported with the NLR and significantly higher than those reported with the MPV. Therefore, the combination of NLR and MPV does not add much to using NLR alone.

This study had several limitations, including the lack of follow-up measures for NLR and MPV during and after antibiotic treatment, which hindered monitoring the impact of SBP treatment on NLR and MPV levels. Additionally, the sample size of the study was relatively small.

Conclusion

In conclusion, NLR and MPV increased significantly in patients with SBP. Although NLR and MPV allowed the detection of SBP, the NLR had higher clinical utility and was superior to MPV in diagnosing SBP.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and supplementary file.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AUC:

-

Area under curve

- CBC:

-

Complete blood count

- CTP:

-

Child-Turcotte-Pugh score

- HBsAg:

-

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- MELD:

-

Model for end-stage liver disease score

- MPV:

-

Mean platelet volume

- MREC:

-

Medical Research Ethics Committee

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio

- NPV:

-

Negative predictive value

- NSAIDs:

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- pH:

-

Power of hydrogen

- PMNL:

-

Polymorphonuclear leukocyte

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

- ROC curve:

-

Receiver operating characteristics curve

- SBP:

-

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

References

Ekpanyapong S, Reddy KR (2019) Infections in cirrhosis. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 17:254–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11938-019-00229-2

Marciano S, Díaz JM, Dirchwolf M, Gadano A (2019) Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with cirrhosis: incidence, outcomes, and treatment strategies. Hepat Med 11:13–22. https://doi.org/10.2147/hmer.s164250

Chinnock B, Afarian H, Minnigan H, Butler J, Hendey GW (2008) Physician clinical impression does not rule out spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients undergoing emergency department paracentesis. Ann Emerg Med 52:268–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.02.016

Rimola A, García-Tsao G, Navasa M, Piddock LJ, Planas R, Bernard B, Inadomi JM (2000) Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a consensus document. International ascites Club. J Hepatol 32:142–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80201-9

Lee JM, Han KH, Ahn SH (2009) Ascites and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: an Asian perspective. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 24:1494–1503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06020.x

Parsi MA, Saadeh SN, Zein NN, Davis GL, Lopez R, Boone J, Lepe MR, Guo L, Ashfaq M, Klintmalm G, McCullough AJ (2008) Ascitic fluid lactoferrin for diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 135:803–807. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.045

Shizuma T (2018) Spontaneous bacterial and fungal peritonitis in patients with liver cirrhosis: a literature review. World J Hepatol 10:254–266. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v10.i2.254

Li B, Ren Q, Ling J, Tao Z, Yang X, Li Y (2021) Clinical relevance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and mean platelet volume in pediatric Henoch-Schonlein purpura: a meta-analysis. Bioengineered 12:286–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/21655979.2020.1865607

Mousa N, Besheer T, Abdel-Razik A, Hamed M, Deiab AG, Sheta T, Eldars W (2018) Can combined blood neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and C-reactive protein be used for diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis? Br J Biomed Sci 75:71–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/09674845.2017.1396706

Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Mikhailidis DP, Kitas GD (2011) Mean platelet volume: a link between thrombosis and inflammation? Curr Pharm Des 17:47–58. https://doi.org/10.2174/138161211795049804

Tekin M, Konca C, Gulyuz A, Uckardes F, Turgut M (2015) Is the mean platelet volume a predictive marker for the diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis in children? Clin Exp Nephrol 19:688–693. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-014-1049-z

Cho SY, Jeon YL, Kim W, Kim WS, Lee HJ, Lee WI, Park TS (2014) Mean platelet volume and mean platelet volume/platelet count ratio in infective endocarditis. Platelets 25:559–561. https://doi.org/10.3109/09537104.2013.857394

Turhan O, Coban E, Inan D, Yalcin AN (2010) Increased mean platelet volume in chronic hepatitis B patients with inactive disease. Med Sci Monit 16:Cr202-205

Seyedi SA, Nabipoorashrafi SA, Hernandez J, Nguyen A, Lucke-Wold B, Nourigheimasi S, Khanzadeh S (2022) Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis among cirrhotic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022:8604060. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8604060

Abdel-Razik A, Mousa N, Abdel-Aziz M, Elsherbiny W, Zakaria S, Shabana W, Abed S, Elhelaly R, Elzehery R, Eldars W, El-Bendary M (2019) Mansoura simple scoring system for prediction of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: lesson learnt. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 31:1017–1024. https://doi.org/10.1097/meg.0000000000001364

Suvak B, Torun S, Yildiz H, Sayilir A, Yesil Y, Tas A, Beyazit Y, Sasmaz N, Kayaçetin E (2013) Mean platelet volume is a useful indicator of systemic inflammation in cirrhotic patients with ascitic fluid infection. Ann Hepatol 12:294–300

Abdel-Razik A, Eldars W, Rizk E (2014) Platelet indices and inflammatory markers as diagnostic predictors for ascitic fluid infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 26:1342–1347. https://doi.org/10.1097/meg.0000000000000202

Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R (1973) Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg 60:646–649. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800600817

Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, D'Amico G, Dickson ER, Kim WR (2001) A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 33:464–470. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2001.22172

Makhlouf N, Morsy K, Mahmoud A, Hassaballa A (2018) Diagnostic value of ascitic fluid lactoferrin, calprotectin, and calprotectin to albumin ratio in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci 7:2618–2631

Amal A, Mahmoud A, Zeinab H, Zeinab A, Eman A, Bahaa A, Mai M, Mohamed G, Mahmoud A, Elzahry MA (2017) Mean platelet volume is a promising diagnostic marker for systemic inflammation in cirrhotic patients with ascitic fluid infection. J Mol Biomark Diagn 8:1–4

Zahorec R (2021) Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, past, present and future perspectives. Bratisl Lek Listy 122:474–488. https://doi.org/10.4149/bll_2021_078

de Jager CP, van Wijk PT, Mathoera RB, de Jongh-Leuvenink J, van der Poll T, Wever PC (2010) Lymphocytopenia and neutrophil-lymphocyte count ratio predict bacteremia better than conventional infection markers in an emergency care unit. Crit Care (London, England) 14:R192. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc9309

Awad SA, Ahmed ES, Mohamed EE (2020) Role of combined blood neutrophil- lymphocyte ratio and c-reactive protein in diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Benha J Appl Sci 5:43–49. https://doi.org/10.21608/bjas.2020.137134

Baweja A, Jhamb R, Kumar R, Garg S, Gogoi P (2021) Clinical utility of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as a marker of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) in patients with cirrhosis-an exploratory study. Int J Sci Res Arch 3:031–042

AH MR, El-Amien HA, Asham MN, Elgendy SG (2022) Can platelets indices and blood neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio be used as predictors for diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in decompensated post hepatitis liver cirrhosis? Egypt J Immunol 29:12–24

Piotrowski D, Sączewska-Piotrowska A, Jaroszewicz J, Boroń-Kaczmarska A (2020) Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio as the best simple predictor of bacterial infection in patients with liver cirrhosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:1727

Badawi R, Asghar MN, Abd-Elsalam S, Elshweikh SA, Haydara T, Alnabawy SM, Elkadeem M, ElKhalawany W, Soliman S, Elkhouly R, Soliman S, Watany M, Khalif M, Elfert A (2020) Amyloid a in serum and ascitic fluid as a novel diagnostic marker of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Antiinflammatory Antiallergy Agents Med Chem 19:140–148. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871523018666190401154447

Andrews RK, Arthur JF, Gardiner EE (2014) Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and the role of platelets in infection. Thromb Haemost 112:659–665. https://doi.org/10.1160/th14-05-0455

Khorshed SE, Ibraheem HA, Awad SM (2015) Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta (MIP-1β) and platelet indices as pre-dictors of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis—MIP, MPV and PDW in SBP. Open J Gastroenterol 5:94

Acknowledgements

The authors express their deep gratitude and thanks to the patients and physicians Nashwa Khalaf Refaie, and Rehab Abd El-Raouf Mohamed, resident doctors in the Tropical Medicine and Gastroenterology Department for their help and support throughout this work.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ahmed Abudeif and Mahmoud Ibrahim Elbadry conceived and designed the study and collected clinical data. Nesma Mokhtar Ahmed performed laboratory work. Mahmoud Ibrahim Elbadry conducted data analysis and figures design. Ahmed Abudeif and Mahmoud Ibrahim Elbadry wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was accepted by The Medical Research Ethics Committee (MREC) of the Sohag Faculty of Medicine (IRB number: Soh-Med-21-02-22). All participants gave informed written consent before enrolment in the study, or their family members (for patients who were unconscious).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1.

Baseline demographic, clinical, ultrasonographic, and laboratory characteristics of the studied cohort.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abudeif, A., Elbadry, M.I. & Ahmed, N.M. Validation of the diagnostic accuracy of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and mean platelet volume (MPV) in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Egypt Liver Journal 13, 9 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-023-00245-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-023-00245-z