Abstract

Background

Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation (EPLBD) after sphincterotomy (EST) was introduced for the removal of large (≥ 10 mm) or multiple bile duct stones. This method combines the advantages of EST and EPLBD by increasing the efficacy of stone extraction while minimizing complications of EST and EPLBD when used alone. This prospective study aimed to compare between EPLBD with prior limited EST and sole sphnicterotomy for extraction of multiple and/or large common bile duct stones.

Results

Statistical analysis revealed insignificant difference between the studied groups as regards the presence of periamullary diverticulum (23% vs. 19%, P > 0.05) and the use of mechanical lithotripsy (4% vs. 9%, P > 0.05). The rates of overall and initial stone clearance were not significantly different between both groups [94% vs. 90%), P > 0.05; and 84% vs. 78%, P > 0.05, respectively]. The procedure-related pancreatitis and bleeding in EST/EPLBD group were lower compared to EST group (3% vs. 5%, P > 0.05; and 2% vs. 6%, P > 0.05, respectively). None of the studied groups’ patients died or developed procedure-related perforation or cholangitis.

Conclusion

Endoscopic large balloon dilation with prior limited sphincterotomy is an effective and safe endoscopic technique for removing multiple and/or large CBDSs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Common bile duct stones (CBDSs) are present in about 4–10% of patients who have undergone cholecystectomy. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has been used as the first choice therapy for the treatment of CBDSs because of its high success rate, low invasiveness, low incidence of complications, and mortality [1].

Endoscopic sphincterotomy is the standard method for enlarging the CBD opening in the duodenum before stone removal during ERCP. Although EST is effective, it may be accompanied by short-term and long-term complications [2].

Therefore, another less invasive technique, endoscopic papillary balloon dilation (EPBD), has been used to facilitate the extraction of CBDSs while preserving the biliary sphincter function especially in patients with coagulopathy, cirrhosis, and unfavorable anatomy [3].

The efficacy of endoscopic balloon dilation is similar to sphincterotomy in the extraction of small to moderate sized stones (1–9 mm). However, it frequently requires additional procedures, such as endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy (EML), especially in the removal of large stones (> 10 mm) [4].

Ersoz et al. recommended a modification of EPBD which combined large balloon dilation (12–20 mm) with a limited papillary precut. This technique combines the advantages of sphincterotomy and EPBD by increasing the efficacy of stone clearance while minimizing the complications of sphincterotomy and EPBD when used alone [5].

Therefore, this prospective study aimed at evaluating the efficacy and safety of EPLBD after limited EST in comparison to sole sphincterotomy for the extraction of multiple and/or CBDSs.

Patients and methods

This prospective randomized comparative study was conducted on 200 patients with CBD obstruction by multiple and/or large stone(s). They were selected from 960 patients who were referred to the endoscopy units of Tropical Medicine Department, Menoufia University Hospitals, and Hepatogastroenterology Department, National Liver Institute, Menoufia University for ERCP in the period between April 2019 to March 2021. The excluded 760 patients were presented with either current or previous pancreatic disease, CBD strictures, hepatobiliary surgery, infection, single CBD stone (Fig. 1)

The required sample size was calculated to be 100 patients per group as it has been calculated at 95% power, 90% non-inferiority margin, that reported the overall adverse event rate of 15% on EPLBD with EST based on past review of literature [5]. So, the patients were classified into two groups according to the order of the procedure, 100 patients were subjected to endoscopic large balloon dilation with prior sphincterotomy (EST/EPLBD) (group I) and 100 patients were subjected to sole endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) (group II). The study was approved by the local ethics committee of Faculty of Medicine, Menoufia University (Approval No. 32019Trop) and according to the Helsinki Declaration, and informed consents were taken from all patients included in this study.

Before the endoscopic procedure, all patients were subjected to full clinical assessment, laboratory investigations such as [complete blood count, liver function tests (bilirubin, alanin transaminase, aspartate transaminase, GGT, alkaline phosphatase, and prothrombin time) and measurement of serum amylase and lipase before and 24 h after ERCP] and imaging studies (pelvi-abdominal ultrasound and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography).

Endoscopic procedure

After overnight fasting, the patients were put in the prostrate position and connected to the anaesthetic apparatus and according to their general condition; the anaesthesiologists used either general anaesthesia or deep sedation by IV propofol infusion (50–200 mcg/kg/min) and/or midazolam (0.25–1 mcg/kg/min).

ERCP was performed using side-viewing duodenoscope (JF-260 or TJF-260;Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The C arm was SIEMENS AXIOM Sireskop SD and the ERBE ICC 200 device was used for automatic cutting or coagulation using a blended current of 40 W cutting and 35 W coagulation. Selective cannulation of the bile duct was attempted with the tip of the sphinctertome (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) dipped 2–3 mm inside the ampulla and oriented to the common bile duct, a soft hydrophilic tipped teflon 0.035 inch wire (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA or Wilson Cook, Winston Salem, NC) was introduced in 2–3 mm increments to gain access to the common bile duct. Adjustments to the orientation of the sphinctertome were done until the guide wire was seen to enter the common bile duct. The guide wire was introduced further into the common bile duct followed by incremental advancement of the sphinctertome and then the contrast was injected to verify common bile duct cannulation. After successful cannulation of CBD, the studied patients were randomly classified by using a computer-generated random number table (prepared by a statistician) into an EST+EPLBD group or sole EST group.

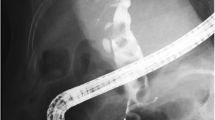

Group I (EST/EPLBD)

Limited sphincterotomy was performed before EPLBD using a 25-mm pull-type papillotome (CleverCut 3V; KD-V411M, Olympus) and extended to a third of the total papillary length and wire-guided hydrostatic balloon catheter (5.5 cm in length, 12 to 20 mm in diameter) (Boston Scientific Microvasive, Cork, Ireland) was introduced across the major papilla with the balloon mid-portion placed at the sphincter of Oddi. Under endoscopic and fluoroscopic control, the hydrostatic balloon was gradually inflated with dilute contrast medium to the pressure equal to the smallest balloon diameter (12–20 mm) until the waist of the balloon had disappeared (Figs. 2 and 3). The pressure for inflation of the balloon was gradually increased till the desired dilation was achieved according to the size of the stones and bile duct proximal to the tapered segment. After that, the balloon was maintained in position for more than two minutes and then deflated and removed.

Group II (EST)

Sphincterotomy was performed with a 20-mm cut-wire sphincterotome (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) with using of the electrosurgical generator (ERBE) in the endocut mode and a needle knife (Boston Scientific) oriented from the 11:00 to 1:00 o’clock position over the maximum convexity of the bulging part of the papilla. The sphincterotomy was done over the mid-region of the papillary orifice and extended upwards carefully to avoid perforation of the duodenum. Inferiorly, the sphincterotomy was not extended to the papillary orifice to avoid the injury to the pancreatic sphincter. Sphincterotomy extending up to the transverse hood is defined as a small (subtotal) EST, whereas large (total) EST extends up to the superior margin of the intramural bile duct.

After the procedure, the common bile duct stones were removed with a Dormia basket or a balloon extractor (Extractor Three Lumen Retrieval Balloon, Boston Scientific Microvasive., Cork, Ireland). Endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy was used to fragment the stones when previous techniques failed to extract the CBDSs. An occlusion cholangiogram was done at the end of the procedure to confirm complete clearance of CBDSs. When the stone had not been completely extracted, a plastic stent was inserted to ensure biliary drainage.

Outcomes

Endoscopic and post-endoscopic assessments were done for technical data, including (technical success rate, overall success rate and the number of therapeutic ERCP procedures required for complete stone clearance), the frequency of use of mechanical lithotripsy and procedure-related complications, including (bleeding, pancreatitis, perforation, and cholangitis).

Post-ERCP complications were defined as procedure adverse effects that necessitated immediate intervention or prolonged duration of hospitalization or required readmission for previously discharged patients. Post-endoscopic pancreatitis was defined as a new onset of abdominal pain with increase in the level of amylase and/or lipase above the upper limit of normal at more than 24 h after the procedure [6]. Procedure-related bleeding was classified as major bleeding (necessitating transfusion or immediate intervention) or minor bleeding (self-limited) [7]. Cholangitis was diagnosed by the presence of Charcot’s triad [6]. Perforation was defined as the leakage of contrast medium into the retroperitoneum or intraabdominal cavity during ERCP or evidence of retroperitoneal-free air on abdominal plain radiography or computed tomography [8].

Statistical analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using SPSS (statistical package for social science/IBM, Chicago, USA) program version 13 for windows. Descriptive statistics were used in which qualitative data were presented in the form numbers and percentages (%) and quantitative data were presented in the form of standard deviation (SD), mean (X), and range. Statistical significance was demonstrated for results (p value < 0.05) using Student’s t test. Chi-square test (χ2) was used to study the association between two qualitative variables.

Results

Demographic data of the 200 patients (119 females (59.5%) and 81 males (40.5%); age ranged between 19 and 83 years) is presented in Table 1. The median CBD stone size was 13.5 mm in group I (EST/EPLBD) and 14 mm in group II (EST) and statistical analysis revealed no significant difference between the studied groups as regards mean stone size (p value = 0.051). Statistical analysis revealed no significant difference between the studied groups regarding the presence of periamullary diverticulum (23% vs 19%, P > 0.05) and the diameter of CBD (18.6 ± 7.43 mm vs 17.5 ± 5.02 mm, P > 0.05) (Table 1).

The use of mechanical lithotripsy and stent insertion were less frequent in group I (EST/EPLBD) compared to group II (EST) and there was a statistical insignificant difference between the studied groups regarding EML and stent insertion [4% vs. 9%, P > 0.05; and 41% vs. 52%, p > 0.05, respectively). Statistical analysis revealed significant lower mean procedure time in EST/EPLBD group compared to EST group (37.530 ± 8.061 vs. 40.790 ± 10.741, P = 0.016). Moreover, although the technical success rate was 100% in both groups, the overall success rate of complete stone clearance was higher with a lower number of ERCP sessions in EST/EPLBD group compared to the sole sphnicterotomy group (Table 2).

The overall complications in EST/EPLBD group were lower compared to EST group, (5% vs. 11%, P = 0.118). The procedure-related pancreatitis and bleeding in EST/EPLBD group were lower compared to SEST group, (3% vs. 5%, P > 0.05; and 2% vs. 6%, P > 0.05, respectively) and all patients with pancreatitis were completely recovered within 72 h of conservative treatment. Moreover, six patients with PEP were younger than 60 years versus two patients aged more than 60 years. None of the studied patients died or developed procedure-related perforation or cholangitis (Table 3).

Discussion

In general, approximately 5–15% of bile duct stones failed to be detached with a single technique of sphincterotomy or EPBD, especially multiple and large CBDSs. Moreover, large common bile duct stone removal might need the concomitant use of EML, which is associated with severe procedure-related complications [9].

EPLBD uses a larger balloon size (12–20 mm) after limited EST is used as an alternative technique for removal of bile duct stones. This technique theoretically combines the advantages of balloon dilation and sphincterotomy by increasing stone extraction efficacy while minimizing the complications of them [10].

The present study revealed nonsignificant differences between the studied groups as regards the presence of periamullary diverticula (23% in EST/EPLBD group vs. 19% in EST group, P > 0.05). This excluded the role of periamullary diverticula in successful cannulation. These results agreed with Kim et al., 2010 [11], and Lee et al., 2011 [12], who demonstrated that the presence or absence of periampullary diverticula did not affect the ERCP procedure in limited EST+EPLBD and sole sphincterotomy groups.

The present study revealed that EPLBD with prior limited sphincterotomy significantly reduced the need for mechanical lithotripsy compared to sole sphincterotomy (4% vs 9%, P > 0.05). These results were in agreement with Guo et al., 2014 [13], and Tsuchida et al., 2015 [14], who reported that combining EPLBD with limited EST significantly decreased the need for EML as it achieved a spacious opening of the common bile duct. On the other hand, Heo et al., 2007 [15], demonstrated that combining EST with EPLBD didn`t significantly reduce the rate of mechanical lithotripsy compared to sole sphincterotomy. Moreover, Stefanidis et al., 2011 [16] and Kim et al., 2016 [17], reported that mechanical lithotripsy is time consuming with high risk of complications and should be replaced by EPLBD in the era of removal of CBD stones.

The present study revealed that the procedure time was significantly shorter in EST/EPLBD group compared with EST group (37.530 ± 8.061 vs. 40.790 ± 10.741, p < 0.05), respectively. These results agreed with Itoi et al., 2009 [18], and Tsuchida et al., 2015 [14], who reported that EPLBD with limited EST significantly decreased the mean procedure time.

The technical success rate in the present study was achieved in all patients of both groups. However, the initial (first session) and overall success rates of complete stone removal were higher in the EST/EPLBD group compared to EST group, (84% vs. 70%, P > 0.05) and (94% vs. 90%, P > 0.05), respectively. These results were similar to the two studies done by Guo et al., 2014 [13], and Chu et al., 2017 [19], who reported insignificant difference between the limited EST+EPLBD and EST group as regards the initial and overall success rates of stone removal, although they were higher in the former group. In addition, Tsuchida et al., 2015 [14], reported a significant higher initial success rate and a significant lower mean number of sessions required for complete stone clearance in EST/EPLBD group (1.12) sessions vs. EST group (1.47), p = 0.002). Moreover, Liu et al., 2019 [20] reported that EPLBD following limited or medium sphincterotomy can make it more effective in stone removal with reduction in the procedure time and the number of endoscopic sessions.

The present study revealed that the overall complications were 5% in the EST/EPLBD group compared to 11% in EST group (P = 0.118). These results agreed with previous reports but varied in their significance. Stefanidis et al., 2011 [16], reported significant lower overall adverse events in EST + EPLBD compared to SEST (4.4% vs. 20%, P = 0.049). In a systemic review of 30 studies done by Kim and Kim, 2013 [21], the overall complications were lower in sphincterotomy combined with EPLBD group than in sole sphincterotomy (8.3% vs 12.7%, OR = 1.60, P < 0.001).

The present work revealed that procedure-related pancreatitis in the EST group was 5% and 3% in EST/EPLBD group. These results agreed with a systematic review done by Junior et al., 2018 [22], who stated that post-endoscopic pancreatitis (PEP) tended to be less common in the EST/ELPBD group than in the EST group, although the difference was not statistically significant. Liao et al., 2012 [23], demonstrated that EPLBD with limited sphincterotomy significantly decreased the risk of PEP by adequate visualization and cannulation of the common bile duct. Furthermore, this technique prevents accidental pancreatic duct cannulation and avoids pressure overload on it.

Hwang et al., 2013 [24], founded that EPLBD with limited sphincterotomy reduced the need for mechanical lithotripsy. This prevented obstruction of the pancreatic duct orifice as a result of papillary edema or spasms induced by EML and therefore, minimizes the post-endoscopic pancreatitis. Moreover, Huang et al., 2018 [25], reported that endoscopic nasobiliary drainage catheters significantly lowered PEP. Therefore, Guo et al., 2015 [10] and Park et al., 2018 [26], recommended routine postprocedure biliary drainage to minimize PEP. Furthermore, Park et al., 2018 [26] stated that endoscopic experiences with peri-procedural patients’ optimization are essential in the prevention of PEP.

The present study revealed that six patients with PEP were younger than 60 years versus two patients aged more than 60 years. These results agreed with Weinberg et al., 2006 [27], who reported that PEP was higher in patients aged less than 60 years compared to those above 60 years, and the authors attributed that to the progressive decrease in pancreatic exocrine function with a lower risk of pancreatic injury with aging.

The present study revealed that procedure-related bleeding in the sole sphincterotomy group was 6% compared to 2% in EST/EPLBD group, (P = 0.306). There was a case of major bleeding in SEST group that required blood transfusion and hemostatic therapy, and seven cases had minor bleeding (2 in group I and 5 in group II) that was controlled by administration of hemostatic agents. Guo et al., 2014 [13], reported that the procedure-related bleeding was lower in EST/EPLBD group in comparsion to EST group [1/64 (1.6%) vs. 5/89 (5.6%), P < 0.05]. The lower risk of bleeding in EPLBD with prior limited EST group may be related to prevention of bleeding by effective compression done by the balloon and this technique may be recommended specially in patients with high risk of bleeding such as patients on anticoagulant therapy as well as patients with cirrhosis or end stage renal diseases [28].

None of the studied groups’ patients died or developed procedure-related perforation or cholangitis. These results agreed with Aujla et al., 2017 [29], who demonstrated that there was no reported cases of perforation, cholangitis, or mortality in either group. In contrast to the study done by Guo et al., 2014, who reported that there was two cases in sphincterotomy group died from multiple organ failure. Moreover, he reported that the lower risk of procedure-related duodenal perforation in EST/EPLBD group compared to sphincterotomy group could be related to the ability of the endoscopist to observe ampullary dilation status by side view endoscope and fluoroscopy. Moreover, this lower risk can be minimized by avoiding the size of the dilating balloon to exceed CBD diameter [13]. Many previous studies showed that acute cholangitis developed more often in the sphincterotomy group in comparison to the EPLBD group, and this might be explained by the loss of sphincter function after sphincterotomy, which enables colonization of intestinal organisms into the biliary system [30].

In the current study, the failure of complete stone removal in EST/EPLBD and sole EST groups was (6% vs. 10%, respectively) and this was associated with larger transverse stone diameters (> 2 cm) and all those patients underwent surgical removal of CBDSs. These results agreed with previous reports. Aujla et al., 2017 [29], reported that large CBDSs > 17.4 mm was associated with significant failure of duct clearance. Kuo et al., 2016 [31] and Chu et al., 2017 [19] related failure of complete duct clearance to large stones (1.5–2 cm), present with large periamullary diverticulum and inadequate stone capture by the basket and they recommended open surgery in those patients.

Previous studies have indicated that biliary reflux in the early postoperative period is a major cause for long-term complications such as recurrence of CBDSs with sole sphincterotomy. By the combination of sphincterotomy and EPLBD, the occurrence of biliary reflux was minimized through limiting the damage of the papilla as well as the impairment of sphincter function, thus effectively preventing these complications in patients [19].

There were limitations in the current study. Our study only assessed short-term complications, not long-term complications, which could be important to evaluate the safety of the techniques. Also, a larger sample size or a non-inferiority trial might be necessary to confirm these results.

Conclusion

From the present study, we concluded that EPLBD with prior EST was as effective and safe as sole sphincterotomy in patients with multiple and/or large common bile duct stones and it could be considered a useful alternative modality for the treatment of multiple and/or large CBDSs.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- EPLBD:

-

Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation

- EST:

-

Sphincterotomy

- EML:

-

Endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy

- CBD:

-

Common bile duct

- CBDSs:

-

Common bile duct stones

- ERCP:

-

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatograpphy

- PEP:

-

Post endoscopic pancreatitis

References

Sakai Y, Tsuyuguchi T, Sugiyama H, Sasaki R, Sakamoto D, Nakamura M et al (2015) Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation for bile duct stones in elderly patients. World J Clin Cases 3(4):353–359

Koksal AS, Eminler AT, Parlak E (2018) Biliary endoscopic sphincterotomy: Techniques and Complications. World J Clin Cases 6(16):1073–1086

Minakari M, Samani RR, Shavakhi A, Jafari A, Alijanian N, Hajalikhani M (2013) Endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation in comparison with endoscopic sphincterotomy for the treatment of large common bile duct stone. Adv Biomed Res 2(2):46

Park JS, Jeong S, Lee DK, Jang SI, Lee TH, Park S et al (2018) Comparison of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation with or without endoscopic sphincterotomy for the treatment of large bile duct stones. Endoscopy 51(2):125–132

Ersoz G, Tekesin O, Ozutemiz AO, Gunsar F (2003) Biliary sphincterotomy plus dilation with a large balloon for bile duct stones that are difficult to extract. Gastrointest Endosc 57:156–159

Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC et al (1991) Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc 37:383–393

Arata S, Takada T, Hirata K, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Hirota M et al (2010) Post-ERCP pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 17:70–78

Lim JU, Joo KR, Cha JM, Shin HP, Lee JI, Park JJ et al (2012) Early use of needle-knife fistulotomy is safe in situations where difficult biliary cannulation is expected. Dig Dis Sci 57:1384–1390

Tao T, Zhang M, Zhang QJ, Li L, Li T, Zhu X et al (2017) Outcome of a session of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy before endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for problematic and large common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol 23:4950–4957

Guo Y, Lei S, Gong W, Gu H, Li M, Liu S et al (2015) A preliminary comparison of endoscopic sphincterotomy, endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation, and combination of the two in endoscopic choledocholithiasis treatment. Med Sci Monit 21:2607–2612

Kim HW, Kang DH, Choi CW, Park JH, Lee JH, Kim MD et al (2010) Limited endoscopic sphincterotomy plus large balloon dilation for choledocholithiasis with periampullary diverticula. World J Gastroenterol 16:4335–4340

Lee JW, Kim JH, Kim YS, Choi HS, Kim JS, Jeong SH et al (2011) The effect of periampullary diverticulum on the outcome of bile duct stone treatment with endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation. Korean J Gastroenterol 58:201–207

Guo S, Meng H, Duan Z, Li C (2014) Small sphincterotomy combined with endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation vs sphincterotomy alone for removal of common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol 20(47):17962–17969

Tsuchida K, Iwasaki M, Tsubouchi M, Suzuki T, Tsuchida C, Yoshitake N et al (2015) Comparison of the usefulness of endoscopic papillary large-balloon dilation with endoscopic sphincterotomy for large and multiple common bile duct stones. BMC Gastroenterol 15:59

Heo JH, Kang DH, Jung HJ, Kwon DS, An JK, Kim BS et al (2007) Endoscopic sphincterotomy plus large-balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of bile-duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc 66(4):720–726

Stefanidis G, Viazis N, Pleskow D, Manolakopoulos S, Theocharis L, Christodoulou C et al (2011) Large balloon dilation vs. mechanical lithotripsy for the management of large bile duct stones: a prospective randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol 106:278–285

Kim TH, Kim JH, Seo DW, Lee DK, Reddy ND, Rerknimitr R et al (2016) International consensus guidelines for endoscopic papillary large-balloon dilation. Gastrointest Endosc 83:37–47

Itoi T, Itokawa F, Sofuni A, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K et al (2009) Endoscopic sphincterotomy combined with large balloon dilation can reduce the procedure time and fluoroscopy time for removal of large bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol 104:560–565

Chu X, Zhang H, Qu R, Li C (2017) Small endoscopic sphincterotomy combined with endoscopic papillary large-balloon dilation in the treatment of patients with large bile duct stones. Eur Surg 49:9–16

Liu P, Lin H, Chen Y, Wu Y, Tang M, Lai L (2019) Comparison of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation with and without a prior endoscopic sphincterotomy for the treatment of patients with large and/or multiple common bile duct stones: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Clin Risk Manag 15:91–101

Kim KH, Kim TN (2013) Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation in patients with periampullary diverticula. World J Gastroenterol 19:7168–7176

Junior CC, Bernardo WM, Franzini TB, Luz GO, Santos ME, Cohen JM et al (2018) Comparison between endoscopic sphincterotomy vs endoscopic sphincterotomy associated with balloon dilation for removal of bile duct stones: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. World J Gastrointest Endosc 10(8):130–144

Liao WC, Tu YK, Wu MS, Wang H, Lin J, Leung JW et al (2012) Balloon dilation with adequate duration is safer than sphincterotomy for extracting bile duct stones: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 10:1101–1109

Hwang JC, Kim JH, Lim SG, Kim SS, Shin SJ, Lee KM et al (2013) Endoscopic large-balloon dilation alone versus endoscopic sphincterotomy plus large-balloon dilation for the treatment of large bile duct stones. BMC Gastroenterol 13:15

Huang Q, Shao F, Wang C, Qi W, Qiu LJ, Liu Z (2018) Nasobiliary drainage can reduce the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis after papillary large balloon dilation plus endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol 53(1):114–119

Park JS, Jeong S, Lee DK, Jang SI, Lee TH, Park SH et al (2018) Comparison of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation with or without endoscopic sphincterotomy for the treatment of large bile duct stones. Endoscopy 7:54

Weinberg BM, Shindy W, Lo S (2006) Endoscopic balloon sphincter dilation (sphincteroplasty) versus sphincterotomy for common bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 18:CD004890

Yoon HG, Moon JH, Choi HJ, Kim DC, Kang MS, Lee TH et al (2014) Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation for the management of recurrent difficult bile duct stones after previous endoscopic sphincterotomy. Dig Endosc 26:259–263

Aujla UI, Ladep N, Dwyer L, Hood S, Stern N, Sturgess R et al (2017) Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilatation with sphincterotomy is safe and effective for biliary stone removal independent of timing and size of sphincterotomy. World J Gastroenterol 23(48):8597–8604

Tanaka S, Sawayama T, Yoshioka T (2004) Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation and endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones: long-term outcomes in a prospective randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc 59:614–618

Kuo C, Chiu Y, Liang C, Lu L, Tai W, Kuo Y et al (2016) Limited precut sphincterotomy combined with endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for common bile duct stone removal patients with difficult biliary cannulation. BMC Gastroenterol 16:70

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

(1) Conceptualization: Ali Nada. (2) Data curation: Randa Mohamed. (3) Formal analysis: Randa Mohamed. (4) Funding acquisition: no fund. (5) Investigation: Randa Mohamed. (6) Methodology: Ali Nada. (7) Project administration: Hossam Ibrahim. (8) Resources: Ali Nada. (9) Software: Ahmed Ragab. (10) Supervision: Hossam Ibrahim. (11) Validation: Hossam Ibrahim. (12) Visualization: Ahmed Ragab. (13) Writing—original draft: Ahmed Ragab, Randa Mohamed (14) Writing—review and editing: All authors are included in editing and reviewing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of Faculty of Medicine, Menoufia University (Approval No. 32019Trop), and informed consents were taken from all patients included in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammed, H.I., Nada, A.S.E., Seddik, R.M. et al. Combined endoscopic large balloon dilation with limited sphincterotomy versus sole sphincterotomy for removal of large or multiple common bile duct stones. Egypt Liver Journal 13, 1 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-023-00235-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-023-00235-1