Abstract

Background

There is a pressing need to translate empirically supported interventions, products, and policies into practice to prevent and control prevalent chronic diseases. According to the Knowledge to Action (K2A) Framework, only those interventions deemed “ready” for translation are likely to be disseminated, adopted, implemented, and ultimately institutionalized. Yet, this pivotal step has not received adequate study. The purpose of this paper was to create a list of criteria that can be used by researchers, in collaboration with community partners, to help evaluate intervention readiness for translation into community and/or organizational settings.

Methods

The identification and selection of criteria involved reviewing the K2A Framework questions from the “decision to translate” stage, conducting a systematic review to identify characteristics important for research translation in community settings, using thematic analysis to select unique research translation decision criteria, and incorporating researcher and community advisory board feedback.

Results

The review identified 46 published articles that described potential criteria to decide if an intervention appears ready for translation into community settings. In total, 17 unique research translation decision criteria were identified. Of the 8 themes from the K2A Framework that were used to inform the thematic analysis, all 8 were included in the final criteria list after research supported their importance for research translation decision-making. Overall, the criteria identified through our review highlighted the importance of an intervention’s public health, cultural, and community relevance. Not only are intervention characteristics (e.g., evidence base, comparative effectiveness, acceptability, adaptability, sustainability, cost) necessary to consider when contemplating introducing an intervention to the “real world,” it is also important to consider characteristics of the target setting and/or population (e.g., presence of supporting structure, support or buy-in, changing sociopolitical landscape).

Conclusions

Our research translation decision criteria provide a holistic list for identifying important barriers and facilitators for research translation that should be considered before introducing an empirically supported intervention into community settings. These criteria can be used for research translation decision-making on the individual and organizational level to ensure resources are not wasted on interventions that cannot be effectively translated in community settings to yield desired outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that chronic diseases account for 71% of mortality globally, amounting to 41 million deaths each year [1, 2]. Addressing increasing rates of chronic disease is important to improving health, healthcare spending, and quality of life [3,4,5]. To optimize the use of public health funding, public health and community-oriented practitioners should focus on evidence-based interventions, products, and policies that show promise for implementation in community settings [6]. There is a pressing need to translate empirically supported interventions, products, and policies into practice to prevent and control prevalent chronic diseases.

The Knowledge to Action (K2A) Framework is useful for understanding and informing the process of how research is translated into practice and ultimately institutionalized in public health and community settings [7]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Work Group on Translation, comprised of various divisions within the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, created the K2A Framework [7]. The K2A Framework describes three phases necessary to move knowledge into sustainable action, including the research phase (e.g., efficacy and effectiveness research), the translation phase (e.g., decision to translate knowledge into products, decision to adopt), and the institutionalization phase (e.g., establishing the intervention activities, creating norms within communities) [7, 8]. Moreover, K2A describes the importance of supporting structures within each phase as well as evaluation to move discovery into action [8]. The framework was designed to be relevant regardless of the disease, condition, or risk factor being addressed. K2A also applies to many types of evidence-based programs, policies, interventions, guidelines, tool kits, strategies, and/or messages (hereafter referred to as “interventions”) and works best if research and practice communities are in collaboration [7, 8].

The K2A Framework identifies the “decision to translate” as a pivotal transition step from the research phase to the translation phase. In this step, those responsible for developing or testing the intervention (often the researchers) and those in organizations likely to use them decide whether there is adequate evidence to create an actionable product or to propel an evidence-based intervention into widespread use [8]. Only those interventions deemed “ready” for translation are likely to be disseminated, adopted, implemented, and ultimately institutionalized. Yet, this pivotal step has not received adequate study [9]. Although the K2A framework does have some shortcomings, including that it specifically focuses on evidence-based programs, practices, and policies, and somewhat ignores research products (e.g., tools, indices, technologies) and that it largely targets public health professionals (ignoring the potential use for practitioners or community stakeholders), it is a landmark tool for guiding research translation [8].

In the CDC’s 2018 Request for Applications for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Centers, applicants were required to describe how they would undertake three activities related to translation: (1) propose a prevention research and translation agenda, (2) engage translation partners to increase the translation of research findings into public health practice, and (3) conduct activities to support the translation of center products. In response to the second and third required activities, the University of South Carolina Prevention Research Center proposed to establish criteria to determine if a product or program resulting from our Center’s research is ready for translation and to solicit feedback from community stakeholders on the criteria. These criteria can then be used to prioritize interventions for translation, determine what adaptations may be necessary for translation into a specific setting, and determine whether additional training or resources are needed for the intended audience.

This paper describes the process used to establish criteria for the decision to translate and highlights considerations that can be used to evaluate or compare empirically supported interventions and their readiness for translation. Much has been published in the field of implementation science about factors that influence the adoption, implementation, and dissemination of evidence-based interventions [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Some of these factors likely apply to the decision to translate interventions, while others may not. Furthermore, unlike models that guide the study of adoption, implementation, and dissemination, comprehensive frameworks or models do not appear to exist to help researchers and organizational partners decide which interventions are most suitable for translation [13]. Nonetheless, establishing criteria for the decision to translate can be informed by several areas of investigation, including “designing for dissemination,” [20] consideration of specific intervention characteristics that facilitate research translation and dissemination [21,22,23,24], and review of factors important for implementation [15,16,17, 25, 26]. Such criteria are especially needed in community-based research, where researchers, public health-related agencies, and organizations collaborate. The voices of community partners are critical in this process, as they can enhance the quality and relevance of translated research [27].

The purpose of this paper was to create a holistic list of criteria that can be used by researchers, in collaboration with community partners, to help evaluate intervention readiness for translation into community and/or organizational settings. Specifically, research objectives include (1) systematically review existing literature focused on factors influencing translation of empirically supported interventions into community settings and (2) develop a list of factors that have influenced community translation of empirically supported interventions in past research that can be used as criteria for the decision to translate. Since the K2A framework is a well-known planning tool that uniquely highlights the decision to translate and other key aspects of the research translation phase [7], it was used to inform this systematic review. Specifically, the K2A Framework was a starting point in this process and was augmented by a systematic literature review combined with consideration of researcher and community partner input.

Methods

The identification and selection of criteria began with a review of K2A questions from the “decision to translate” stage and then involved conducting a literature review to identify characteristics important for research translation in community settings, using thematic analysis to select unique research translation decision criteria, and soliciting and incorporating researcher and community advisory board feedback.

Knowledge to Action (K2A) Framework

The “decision to translate” stage of the K2A Framework includes 8 planning questions to help decide whether an intervention is ready to move forward for translation (e.g., Is this intervention needed? Is there broad support or buy-in to translate the intervention into practice?) [8]. These questions were converted to items on our coding manual and were used as a starting point for developing criteria for the decision to translate research.

Literature review search strategy

Our next step was to conduct a systematic literature review to understand criteria or factors presented in past research that were relevant to research translation. The review included academic literature identifying criteria for deciding which empirically supported interventions could be effectively translated into practice as well as articles that more generally identify factors relevant to the translation process. PubMed and Google Scholar were searched for peer-reviewed articles published between January 2000 and August 2020. The primary goal of this review was to identify the most prominent literature on research translation and related decisional criteria, so we did not undertake the time-consuming task of integrating a comprehensive list of academic databases. Although some published research identifying factors that impact research translation may not have appeared in our searches, it is unlikely that critical criteria were missed that were not captured by these two databases. PubMed contains more than 32 million citations for biomedical literature from MEDLINE, life science journals, and online books, and Google Scholar contains 389 million records and is currently the most comprehensive academic search engine [28, 29].

A broad initial literature search was performed to identify common terms related to our review and to develop the final search strategy. In turn, we developed and used the following search terms: ‘translation’ OR ‘knowledge translation’ OR ‘integrated knowledge translation’ OR ‘research translation’ OR ‘research to translation’ OR ‘translation decision’ AND (‘criteria’ OR ‘decision’ OR ‘designing for dissemination’ OR ‘community setting’) under the category “Title/Abstract” between January 2000 and August 2020. We chose to only include publications after the year 2000 to ensure our findings on community interventions were relevant and to reflect important developments in the field of implementation science (e.g., creation of frameworks for community implementation) [7, 30, 31]. In the search terms, we also included names of prominent authors that have published on the topic of research translation to identify additional relevant papers.

Process for literature review study selection

Eligibility criteria included (1) research with human subjects, (2) research published in English, (3) research published between 2000 and 2020, (4) peer-reviewed articles or academic literature, and (5) research conducted in community settings. Specifically, community-based research was the focus of this review due to its relevance to our research team, and because the differences in the application and scope of research translation between community versus clinical settings can be substantial. Community settings were defined as “settings for which the primary purpose is not medical care, for example, geographic communities, schools, churches, homeless shelters, worksites, libraries” [32]. Research in community settings can include studies conducted over the phone, online, or in-person that engage groups of people or organizations that are defined by a function, geography, shared interests, or specific characteristics [33].

Titles and abstracts of articles identified through the search strategy were imported into Zotero, and duplicates were removed. Articles were evaluated for eligibility based on the criteria previously stated (i.e., community setting, human subjects, including criteria that could inform the decision to translate research) by a first reviewer (MW). An additional reviewer (SW), with substantial expertise in the field of research translation, provided input throughout the process towards improving the search terms and identifying relevant articles. At the critical full-text review stage, remaining articles were independently screened for eligibility by the first reviewer (MW), while a second reviewer (ZR) screened all articles using the same eligibility and inclusion criteria. One reviewer (MW) compiled data from each article in a Microsoft Excel database, including titles/authors, publication year, objectives, translational products, criteria/factors identified as important for community translation, and literature gaps addressed. Secondary reviewers (SW, ZR) checked data entry for accuracy and completeness. Discussions were held among all reviewers to resolve any remaining conflicts on article inclusion.

Criteria development and selection

The criteria identified from the literature review, including criteria from the K2A Framework that were also noted in selected articles, were combined to form a full list of potential criteria. One researcher (MW) reviewed the full-text articles identified in the literature review for the presence of the constructs related to the decision for research translation of interventions. The researcher used a deductive and inductive thematic analysis approach, guided by constructs of the K2A framework (i.e., codes related to importance of evidence base, relation to a high-priority public health issue, alignment with constituent needs, comparability to other interventions, support or buy-in for translation, presence of supporting structures, economic considerations, adaptability to contextual changes) [34,35,36]. Emergent themes included any factors that past literature highlighted as important for research translation or dissemination or factors that specifically impacted research translation or dissemination for a certain intervention in practice. Each article was independently reviewed by one researcher (MW), who met periodically throughout the entire article review process to discuss findings with a second expert (SW) and adapt the review process when necessary. In these discussions, the researchers decided that themes that identify intervention and population-level barriers or facilitators to research translation should be included in the criteria list. As an example, some studies reported results from the evaluation of interventions and noted decisions that were made about how to move a study from a controlled pilot to wide-scale dissemination. Other articles described the contextual factors that were advantageous for translating research into community practice.

These resultant criteria were subsequently reviewed by three researchers and members of the University of South Carolina Prevention Research Center Community Advisory Board to improve the language and ensure all criteria were relevant and no criteria were overlooked. All three researchers had familiarity or expertise in research translation and/or community-based participatory research. Thirteen Community Advisory Board members were from diverse sectors, including faith-based organizations, public health, economic and community development, physical activity and healthy eating coalitions, and community-based research initiatives. Community Advisory Board members were led through a process where they generated factors that are most important in their decision to use evidence-based programs, reviewed the criteria developed by the Center, and provided input as to whether any criteria were missing, should be removed, or should be revised. Since these criteria were being developed for use by our university’s Prevention Research Center, incorporating community and research input from nationally representative locations was outside the scope of this study.

Data synthesis

Upon receiving community and expert input on the research translation decision criteria identified through our systematic review, we identified the frequency of articles mentioning each and ordered our criteria list according to the most cited (i.e., each item’s usefulness in past research). We also identified underlying frameworks used in each article to guide translation/implementation research, since this may have influenced the respective authors’ focus when outlining possible research translation criteria or factors. Lastly, we identified the frequency in which articles mentioned research translation criteria that were part of the K2A framework (the framework orienting this research).

Results

Study selection — objective 1

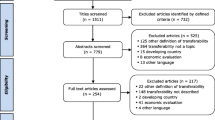

As shown in Fig. 1, the search terms returned 18,654 results, and a total of 66 relevant articles were included after an abstract review. After reviewing the reference lists in the selected articles and incorporating papers from other sources, 20 additional articles were identified as relevant to this review. Two reviewers (MW and ZR) screened full-text articles using the same eligibility and inclusion criteria. Their agreement rate was 88%. After a full-text review of the 86 articles identified, 40 articles were removed because they did not contain findings specific to community settings and/or did not focus on research translation. A final list of 46 articles was used to develop the research translation decision criteria for this article (Fig. 1). Information was compiled for each article identified in our search about the interventions that were being translated and the criteria that might be useful for research translation decisions (Table 1).

Study characteristics — objective 1

The criteria for research translation used in past research outlined in Table 1 include important considerations that facilitate research translation, including contextual, organizational, or intervention characteristics. Several referenced one or more theoretical frameworks or models (n=22): ten used the Reach, Effectiveness, Maintenance, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework [20, 22, 37, 40, 41, 43, 52, 59, 60, 77], four used the Interactive Systems Framework [45,46,47, 50], two used Diffusion of Innovations theory [20, 52], two used CFIR [51, 58], one used the Predisposing, Reinforcing, and Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation & Policy, Regulatory, and Organizational Constructs in Educational and Environmental Development (PRECEDE PROCEED) framework [41], one used the Pragmatic-Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary (PRECIS) model [59], one used the National Institute of Environmental Health Research translational research framework [67], and one used the Evidence Integration Triangle model [59]. A total of 24 articles did not explicitly mention theoretical frameworks or models that were used to develop or apply research translation decision criteria.

Result synthesis — objective 2

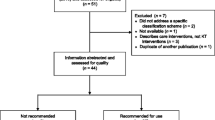

Table 2 and Fig. 2 display the 17 research translation decision criteria identified through our literature review and thematic analysis. Of the 8 themes from the K2A Framework that were used to inform the thematic analysis, all 8 were included in the final criteria list after research supported their importance for research translation decision-making (Table 2, criteria 1–8). Nine additional criteria were identified in the literature that were unrelated to the K2A Framework (Table 2, criteria 9–17). During the review phase, no additional criteria were added by the researchers or Community Advisory Board members. Wording changes were suggested by the Community Advisory Board members to improve the simplicity and coherency of select criteria. For example, Community Advisory Board members suggested that wording in one instance be changed from “does not disempower marginalized communities” to “empowers communities.” The following paragraphs describe each criterion, including citations for review articles that highlight their usefulness and application.

As stated previously, the first 8 criteria in the list (Table 2, Fig. 2) were adapted from the K2A Framework. The first criterion is that the intervention has an adequate evidence base or that efficacy, effectiveness, or implementation studies demonstrate positive public health impacts of the intervention (e.g., research shows clinically significant benefits) [8]. Several articles (n = 20) identified in the literature search also noted this consideration for research translation [8, 22, 37,38,39,40,41, 47, 49, 51, 56, 58,59,60, 63, 65, 67, 69, 71, 73, 74], and specifically cited the importance of internal and external validity of evidence. The second criterion is that the intervention addresses a high-priority public health issue [8]. This means that the intervention addresses a chronic or acute disease affecting a significant portion of the population in the context where it is being implemented (n = 2 articles mentioned this) [8, 22, 59]. The third criterion is that the intervention meets the needs of constituents [8]. Specifically, it is important that the intervention fits with goals, norms, and practices of the population it is serving and is consistent with organizational and program needs (n = 12 articles mentioned this) [8, 21, 42, 44, 51,52,53, 56, 58, 60, 62, 65, 74]. Interventions must also maintain their same meaning after being adapted to fit the community needs [56]. The fourth criterion is that the intervention is comparable to or exceeds outcomes achieved from other available interventions [8]. The intervention should be better than available interventions or comparable but perhaps better suited for the context or population (i.e., there is a relative advantage) (n = 5 articles mentioned this) [8, 25, 41, 47, 51, 73]. The fifth criterion is that there is broad support and/or buy-in to translate the intervention into practice [8]. Research shows that the involvement of key stakeholders and implementation champions early on in the implementation process and proper organizational support are crucial for intervention success (n = 26 articles mentioned this) [8, 21, 25, 33, 39, 40, 42, 44, 46, 47, 49, 51, 54, 57,58,59, 64, 66,67,68,69, 72,73,74,75,76]. One article specifically noted the importance of having proper leadership support, with program goals and a vision that align [47]. The sixth criterion is that there are supporting structures in place (or can be put in place) to support the implementation of the intervention [8]. Resources, training programs, technical assistance, and time are necessary for proper translation, as well as the absence of competing demands, financial and organizational instability, and prevailing practices that work against the intervention goals (n = 26 articles mentioned this) [8, 14, 20,21,22, 25, 33, 39, 42, 44, 46, 47, 49,50,51,52, 54, 57, 58, 60, 62, 64, 70,71,72,73]. The seventh criterion deals with the economic evaluations of research translation, specifically that the intervention is cost-efficient and cost effective [8]. Interventions can be costly, and financial support can be hard to obtain or unreliable and can inhibit implementation efforts (n = 6 articles mentioned this) [8, 22, 25, 47, 51, 55, 60]. If funding and/or donations are available for translating the intervention, there should be some evidence that the investment will yield adequate public health impacts [8]. The eighth criterion adapted from K2A is that changes to the background or contextual factors do not adversely impact the relevance of the intervention [8]. The intervention must be amenable to changes in leadership, the sociopolitical climate, time-related barriers, or other contextual issues (n = 8 articles mentioned this) [8, 25, 40,41,42, 52, 60, 66, 67].

Additional criteria identified in the literature review are also displayed in Table 2 (and Fig. 2) and represent considerations that were not directly addressed in the K2A Framework. The ninth criterion is that the intervention must be very low cost or funding and resources must be available to sustain its implementation (n = 14 articles mentioned this) [21, 22, 25, 33, 37, 42, 46, 51,52,53, 55, 58, 73, 75]. In many contexts, funding may be scarce or unavailable but resource sharing options can promote translation and implementation [51]. The tenth criterion states that intervention must be adaptable to different settings, contexts, or audiences or at least the setting or context under study (n = 15 articles mentioned this) [14, 21, 37, 41,42,43,44, 47, 51, 52, 55, 57, 59, 61, 73]. This was a major consideration in included articles, since interventions were often translated in understudied locations/contexts. Criterion eleven underlines the importance that the intervention is culturally appropriate (n = 8 articles mentioned this) [33, 45, 48, 51, 54, 68, 72, 73], especially when health departments, academic units, or other external institutions with a history of unethical practices are involved [78,79,80,81]. As an example, researchers must continue to acknowledge past incidents, such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, that promote distrust for scientific institutions among populations of certain cultural, racial, and/or ethnic backgrounds [80]. Researchers cannot begin to understand and overcome low participation in public health research and programming without openly acknowledging the larger, historical context in which discrimination within the scientific community has led to mistreatment, denial of basic health care, and even death [45, 80, 81]. Adding to this, researchers must ensure interventions have culturally specific characteristics that may increase participation and positive reception [45]. Criterion twelve states that it is important that the intervention empowers communities through translation efforts (n = 3 articles mentioned this) [45, 48, 58]. Research translation should be community driven, meaning that local stakeholders and community members are ultimately autonomous over the intervention planning and participate in the translation process so that it properly addresses the community’s needs [45]. As well, criterion thirteen states that interventions that include multiple activities tend to be more effective because if one activity cannot be implemented, is not effective, or does not gain community interest, the intervention can still be carried out and have positive impacts (n = 1 article mentioned this) [21]. Criteria fourteen, fifteen, and sixteen relate to intervention sustainability: the intervention must be able to be sustained over time through strategic planning efforts (n = 6 articles mentioned this) [40, 42,43,44, 46, 52]; the intervention must be easy to learn, understand, and use for implementers and community members alike (n = 3 articles mentioned this) [21, 25, 42]; and the intervention should be packaged or manualized for easier implementation (n = 4 articles mentioned this) [42, 43, 52, 60]. Lastly, criterion seventeen states that there must be evidence that the intervention can be implemented sufficiently to yield meaningful public health impacts (n = 3 articles mentioned this) [37, 52, 56]. These can be shown through preliminary studies and can be assessed or considered before translation is initiated.

Discussion

Overall findings

This paper outlined the process used to identify and compile criteria that can be used by researchers and community partners to evaluate or compare interventions and their readiness for translation. As stated, the K2A Framework’s “decision to translate” planning questions, a literature review, a thematic analysis, and consideration of researcher and community partner input were used to develop these criteria. While there is growing interest in this research area, there is little current literature specifically on the decision to translate empirically informed interventions for public health and community-oriented researchers and practitioners, with only seven papers identified [38, 40, 42, 45, 56, 58, 75]. Additionally, there is a breadth of literature on factors that impact the research translation process more generally that were used to inform the resultant research translation decision criteria. Our literature review resulted in a final list of 17 criteria that may be useful for deciding whether an empirically informed intervention should be prioritized for translation in a community or organization. While each of these criteria is important, it is likely that an intervention will not meet all of those listed here. Nonetheless, these criteria can be used to assess readiness for translation by applying a holistic list of considerations to one intervention at a time, or they can be used to draw comparisons between well-researched interventions and assist with decision-making on which intervention should take precedence for translation efforts. Overall, the criteria identified through our review highlighted the importance of an intervention’s public health, cultural, and community relevance when considering its potential for research translation. Not only are intervention characteristics (e.g., evidence base, sustainability, cost) necessary to consider when contemplating introducing an intervention to the “real world,” it is also important to consider characteristics of the target setting and/or population (e.g., presence of supporting structures, support/buy-in).

Comparison to past research

The criteria development outlined in this paper was informed by the K2A Framework, although there were important similarities and differences between that existing framework and the factors identified through our literature search. To start, economic evaluations were highlighted as particularly important in the K2A Framework [7, 8]. The importance of economic considerations was additionally supported by research identified from our literature review, specifically stating that the intervention must be low-cost and the community or organizational context must have funding and resources must be available to sustain its implementation [22, 25, 42, 51, 53, 55]. The K2A Framework also lists that interventions must be adaptable to contextual changes over time [7, 8]. Through our review, we discovered literature stating that the intervention must be adaptable to different settings, contexts, or audiences (and particularly those under study) [14, 21, 41,42,43,44, 47, 51, 61]. Next, K2A Framework research translation considerations state that the intervention must meet the needs of constituents [7, 8]. Research identified by our literature review expands on this, by highlighting the importance of culturally appropriate interventions that empower communities [45, 48, 58]. Here, the research pointed to the importance of autonomy for community members and stakeholders, which was not specifically outlined in the K2A Framework. As another example of our literature review identifying gaps, we built on the K2A highlighting that supporting structures (e.g., appropriate resources, training, technical assistance) must be in place [7, 8] by also including that interventions must be properly manualized to ensure quality assurance and control [42, 43]. Lastly, the K2A Framework states that interventions must address a high-priority public health issue [7, 8]. We learned throughout our literature search that an intervention must be able to be implemented sufficiently to yield meaningful public health impacts, which provides an additional consideration for understanding how to address the public health issue at hand [37, 52, 56]. In summary, there is important overlap and also clear distinctions between the criteria identified using the K2A Framework and the criteria developed through our literature review and consulting process.

Results from our review showed that several theoretical frameworks have been used in the past to make decisions around research translation, dissemination, implementation, and program planning [82, 83]. The frameworks identified in this study showed similarities and differences to the K2A Framework, which served as the foundation for our research translation decision criteria. For instance, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) promotes implementation theory development and research translation in community settings [51, 84, 85]. CFIR overlaps with the K2A Framework in important ways, and we integrated some CFIR components throughout our criteria development process. For instance, CFIR notes the importance of evaluating intervention evidence strength and quality, adaptability, complexity, packaging, and cost before deciding to translate or implement [51]. Moreover, CFIR states that inner and outer setting characteristics, such as the needs/resources of community members, external policies/incentives, and other structural or contextual factors, must be considered before deciding to translate an intervention to a specific community [51]. External policies, such as public funding opportunities for public health initiatives, and their impact on community buy-in and support are particularly important to consider for research translation [86]. Some citizens and communities even argue there is “overreach” by public health institutions when translating cost-intensive interventions, so it is crucial to properly justify the use of public funds and consider all points of view when evaluating the “contextual factors” outlined in our criteria list [86].

The RE-AIM framework was also identified in the literature on factors influencing research translation and is generally used as a method of systematically considering the strengths and weaknesses of interventions to guide program planning so that the public health impact is maximized [87]. Factors noted as important for research translation and implementation for RE-AIM include the cost of the intervention for community members, the potential for the intervention to yield positive outcomes (based on research), the presence of necessary resources and expertise within the community, the benefit of the intervention compared to existing programs, and the extent to which the intervention can be flexible and maintained over time [87]. Although this framework focuses more on contextual factors than intervention characteristics, these factors are important to consider before translating an intervention to a specific setting.

Implications for research and practice

The literature review process and resultant research translation decision criteria outlined in this paper have important implications for public health research. First, public health researchers can study whether using our research translation decision criteria has an impact on intervention translation, implementation, dissemination, and maintenance in more diverse locations and applications. Researchers may even wish to develop ways to “grade” interventions on their ability to meet each criterion using a rating scale for comparison and to ensure assessments of whether an intervention meets related criteria are reliable. Second, researchers can identify whether our research translation decision criteria have a salient impact in specific communities or populations (i.e., those outside our local community where the criteria were developed), or for specific types of intervention (e.g., behavioral interventions, structural interventions). While creating a holistic list of research translation criteria is an important contribution to the literature, we recognize that some criteria may be less relevant depending on the context or intervention type, so researchers may wish to reduce the list to something less comprehensive or weight the importance of certain criteria more heavily for their application. Third, researchers should continue to identify intervention or community factors that impact research translation by reviewing relevant literature, collecting necessary data during intervention translation phases, and incorporating feedback from a more nationally representative group of experts and community leaders. Factors that impact research translation in community settings evolve, so they should be studied and monitored over time.

This study also has important implications for public health and community practice. To start, these research translation decision criteria can be applied by researchers and local stakeholders to initiate conversations on potential facilitators and barriers to translation into community settings. As an example, we identified an efficacious intervention (R01HL135220) conducted through our Prevention Research Center and asked the principal investigator to write a brief description of how the intervention met each of our 17 criteria to share with the Community Advisory Board. After considering the criteria and making comparisons with other grant options, the Community Advisory Board decided that the intervention (R01HL135220) was ready for translation and agreed to provide a letter of support for a grant application. Next, these criteria can be applied during earlier stages of the research process (before the research translation phase) so that researchers can design interventions that have adequate potential for translation. This practice is supported by the K2A Framework [7, 8] and a growing body of research aimed at “designing for dissemination,” [20, 52, 61] so that interventions are appropriate and sustainable in community settings. Additionally, considering these criteria may lead to additional research questions (e.g., what is the cost-effectiveness of this intervention?) that must be investigated before proceeding with research translation (a tactic also outlined within the K2A framework). Lastly, academic institutions, research centers, or federal agencies may wish to make policies that require public health researchers and practitioners to focus more on the decision to translate and consider developing criteria (using methods similar to ours) that capture factors that impact translation in their target communities. This provides a more consistent manner for evaluating whether an intervention is ready for translation in a community setting and may result in more reliable practices and consistent outcomes on an organizational level.

Limitations and strengths

Limitations of this research should be noted. First, research translation decision criteria were based solely on peer-reviewed and published English-language articles, so information and related criteria from unpublished studies, non-English literature, or other communication forms (e.g., theses, government reports) are not represented. Second, this literature review only included reliability checking with a second reviewer during the full-text study selection phase. Although we acknowledge that this may have slightly decreased the number of relevant studies or themes identified [88], we made sure to employ pre-specified eligibility criteria, a systematic search strategy, and collaborative assessment and interpretation of findings. Third, due to limited research on the decision to translate research products, we incorporated research on the entire process for research translation, dissemination, and implementation. We believe that factors that influence more upstream, dissemination/implementation processes also play an important role in translation. Fourth, while this criteria development process involved over a dozen local community members and several researchers at our university’s Prevention Research Center, study findings and research translation decision criteria may lack generalizability. Future directions for these criteria may involve gaining more input from experts and community members in more diverse locations.

In addition to the noted limitations, this study has several strengths. To start, we made use of an existing framework (i.e., K2A Framework) to develop research translation decision criteria. Since this framework was developed by the CDC to describe and depict the high-level processes necessary to move from scientific knowledge and interventions into action [7], it served as a strong and empirically informed foundation for our criteria development. Another strength of this study is that it expands on the burgeoning field of research focusing on the decision to translate research interventions since there is a need for more research on this pivotal juncture between academic knowledge and community settings. Lastly, this study and its resultant research translation criteria were initiated to fill a specific need within a specific CDC-funded Prevention Research Center. Our criteria and related development methods can be used in similar Centers nationwide and in diverse locations to ensure researchers are bridging the gap between public health knowledge and action.

Conclusion

This article provides a clear process for criteria development, by outlining our literature review, researcher input, and community engagement stages that were relevant to the research translation decision-making process. Our research translation decision criteria provide a holistic list for identifying important barriers and facilitators for research translation that can be considered before introducing an empirically supported intervention into community settings. Ideally, these criteria can serve as a novel tool for public health researchers and practitioners and provide more consistency in the process of research translation. Future directions for the development of these criteria may involve testing their use and seeking input from researchers and community leaders in more diverse locations to improve their generalizability.

Availability of data and materials

The data extracted from included studies are not publicly available due to possible copyright issues related to reproducing manuscript content but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- K2A:

-

Knowledge to Action

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CFIR:

-

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- RE-AIM:

-

Reach, Effectiveness, Maintenance, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance

- PRECEDE PROCEED:

-

Predisposing, Reinforcing, and Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation & Policy, Regulatory, and Organizational Constructs in Educational and Environmental Development

- PRECIS:

-

Pragmatic-Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary

References

Forouzanfar MH, Afshin A, Alexander LT, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1659–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8.

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases: World Health Organization; 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases. Accessed 21 Oct 2020

Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet. 2009;374(9696):1196–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61460-4.

Ince Yenilmez M. Economic and social consequences of population aging the dilemmas and opportunities in the twenty-first century. Appl Res Qual Life. 2015;10(4):735–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-014-9334-2.

Population Reference Bureau. Fact sheet: aging in the United States. https://www.prb.org/aging-unitedstates-fact-sheet/. Accessed June 7, 2019.

Rimer BK, Glanz K, Rasband G. Searching for evidence about health education and health behavior interventions. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28(2):231–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019810102800208.

Wilson K, Brady T, Lesesne C, NCCDPHP Work Group on Translation. An organizing framework for translation in public health: the knowledge to action framework. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(2) https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2011/mar/10_0012.htm. Accessed 21 Oct 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Applying the Knowledge to Action (K2A) framework: questions to guide planning: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/pdf/k2a-framework-6-2015.pdf

Zhao N, Koch-Weser S, Lischko A, Chung M. Knowledge translation strategies designed for public health decision-making settings: a scoping review. Int J Public Health. 2020;65(9):1571–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01506-z.

Ashcraft LE, Quinn DA, Brownson RC. Strategies for effective dissemination of research to United States policymakers: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01046-3.

Budd EL, deRuyter AJ, Wang Z, et al. A qualitative exploration of contextual factors that influence dissemination and implementation of evidence-based chronic disease prevention across four countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):233. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3054-5.

Rabin BA, Glasgow RE, Kerner JF, Klump MP, Brownson RC. Dissemination and implementation research on community-based cancer prevention: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4):443–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.035.

Davies P, Walker AE, Grimshaw JM. A systematic review of the use of theory in the design of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies and interpretation of the results of rigorous evaluations. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-14.

Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3-4):327–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0.

Hudson KG, Lawton R, Hugh-Jones S. Factors affecting the implementation of a whole school mindfulness program: a qualitative study using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-4942-z.

Ecker AH, Abraham TH, Martin LA, Marchant-Miros K, Cucciare MA. Factors affecting adoption of Coordinated Anxiety Learning and Management (CALM) in Veterans’ Affairs community-based outpatient clinics. J Rural Health. 2020:jrh.12528. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12528.

Seward K, Finch M, Yoong SL, et al. Factors that influence the implementation of dietary guidelines regarding food provision in centre based childcare services: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2017;105:197–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.09.024.

Naylor PJ, Nettlefold L, Race D, et al. Implementation of school based physical activity interventions: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2015;72:95–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.034.

Hage E, Roo JP, van Offenbeek MA, Boonstra A. Implementation factors and their effect on e-Health service adoption in rural communities: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-19.

Brownson RC, Jacobs JA, Tabak RG, Hoehner CM, Stamatakis KA. Designing for dissemination among public health researchers: findings from a national survey in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(9):1693–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301165.

Baker EA, Brennan Ramirez LK, Claus JM, Land G. Translating and disseminating research- and practice-based criteria to support evidence-based intervention planning. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(2):124–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PHH.0000311889.83380.9b.

Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Bull SS, Estabrooks P. The future of health behavior change research: what is needed to improve translation of research into health promotion practice? Ann Behav Med. 2004;27(1):3–12. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2701_2.

Albrecht L, Archibald M, Arseneau D, Scott SD. Development of a checklist to assess the quality of reporting of knowledge translation interventions using the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) recommendations. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-52.

Flay BR, Biglan A, Boruch RF, et al. Standards of evidence: criteria for efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination. Prev Sci. 2005;6(3):151–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-005-5553-y.

Ross J, Stevenson F, Lau R, Murray E. Factors that influence the implementation of e-health: a systematic review of systematic reviews (an update). Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):146. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0510-7.

King E, Boyatt R. Exploring factors that influence adoption of e-learning within higher education: factors that influence adoption of e-learning. Br J Educ Technol. 2015;46(6):1272–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12195.

Skinner JS, Williams NA, Richmond A, et al. Community experiences and perceptions of clinical and translational research and researchers. Prog Community Health Partnersh Res Educ Action. 2018;12(3):263–71. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2018.0050.

Gusenbauer M. Google Scholar to overshadow them all? Comparing the sizes of 12 academic search engines and bibliographic databases. Scientometrics. 2019;118(1):177–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2958-5.

PubMed.gov. National Library of Medicine. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. Accessed 22 Sept 2021.

Bauer MS, Kirchner J. Implementation science: what is it and why should I care? Psychiatry Res. 2020;283:112376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.04.025.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–7. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322.

The Community Guide. Glossary: The Community Guide; 2015. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/about/glossary. Accessed 22 Sept 2021

Mendel P, Meredith LS, Schoenbaum M, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. Interventions in organizational and community context: a framework for building evidence on dissemination and implementation in health services research. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2008;35(1-2):21–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-007-0144-9.

Lencucha R, Kothari A, Hamel N. Extending collaborations for knowledge translation: lessons from the community-based participatory research literature. Evid Policy J Res Debate Pract. 2010;6(1):61–75. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426410X483006.

Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107.

Hamel C, Michaud A, Thuku M, et al. Defining Rapid Reviews: a systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of definitions and defining characteristics of rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;129:74–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.09.041.

Glasgow RE. Translating research to practice: lessons learned, areas for improvement, and future directions. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(8):2451–6. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.26.8.2451.

Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Glasgow RE. The future of physical activity behavior change research: what is needed to improve translation of research into health promotion practice? Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2004;32(2):57–63.

Glasgow RE, Marcus AC, Bull SS, Wilson KM. Disseminating effective cancer screening interventions. Cancer. 2004;101(S5):1239–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20509.

Klesges LM, Estabrooks PA, Dzewaltowski DA, Bull SS, Glasgow RE. Beginning with the application in mind: designing and planning health behavior change interventions to enhance dissemination. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29(2):66–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2902s_10.

Green LW, Glasgow RE. Evaluating the relevance, generalization, and applicability of research: issues in external validation and translation methodology. Eval Health Prof. 2006;29(1):126–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278705284445.

Glasgow RE, Emmons KM. How can we increase translation of research into practice? Types of evidence needed. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28(1):413–33. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144145.

Prohaska TR, Peters KE. Physical activity and cognitive functioning: translating research to practice with a public health approach. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(2S):S58–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2007.01.005.

Flaspohler P, Duffy J, Wandersman A, Stillman L, Maras MA. Unpacking prevention capacity: an intersection of research-to-practice models and community-centered models. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3-4):182–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9162-3.

Guerra NG, Knox L. How culture impacts the dissemination and implementation of innovation: a case study of the families and schools together program (FAST) for preventing violence with immigrant Latino youth. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3-4):304–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9161-4.

Livet M, Courser M, Wandersman A. The prevention delivery system: organizational context and use of comprehensive programming frameworks. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3-4):361–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9164-1.

Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, et al. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: the interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3-4):171–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9174-z.

Scharff DP, Mathews K. Working with communities to translate research into practice. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(2):94–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PHH.0000311885.60509.61.

Arrington B, Kimmey J, Brewster M, et al. Building a local agenda for dissemination of research into practice. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(2):185–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PHH.0000311898.03573.28.

Saul J, Duffy J, Noonan R, et al. Bridging science and practice in violence prevention: addressing ten key challenges. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3-4):197–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9171-2.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

Prochaska JJ, Fromont SC, Hudmon KS, Cataldo JK. Designing for dissemination: development of an evidence-based tobacco treatment curriculum for psychiatry training programs. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2009;15(1):24–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390308329536.

Green LW, Ottoson JM, García C, Hiatt RA. Diffusion theory and knowledge dissemination, utilization, and integration in public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30(1):151–74. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100049.

Van Olphen J, Green L, Barlow J, Koblick K, Hiatt R. Evaluation of a partnership approach to translating research on breast cancer and the environment. Prog Community Health Partnersh Res Educ Action. 2009;3(3):213–26. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.0.0081.

Ritzwoller DP, Sukhanova A, Gaglio B, Glasgow RE. Costing behavioral interventions: a practical guide to enhance translation. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37(2):218–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9088-5.

Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline: validation of instruments or scales. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(2):268–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01434.x.

Meyers DC, Durlak JA, Wandersman A. The quality implementation framework: a synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;50(3-4):462–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9522-x.

Cilenti D, Brownson RC, Umble K, Erwin PC, Summers R. Information-seeking behaviors and other factors contributing to successful implementation of evidence-based practices in local health departments. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2012;18(6):571–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0b013e31825ce8e2.

Glasgow RE. What does it mean to be pragmatic? Pragmatic methods, measures, and models to facilitate research translation. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(3):257–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198113486805.

Phillips SM, Alfano CM, Perna FM, Glasgow RE. Accelerating translation of physical activity and cancer survivorship research into practice: recommendations for a more integrated and collaborative approach. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2014;23(5):687–99. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1355.

Cohen EL, Head KJ, McGladrey MJ, et al. Designing for dissemination: lessons in message design from “1-2-3 Pap”. Health Commun. 2015;30(2):196–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.974130.

Neta G, Glasgow RE, Carpenter CR, et al. A framework for enhancing the value of research for dissemination and implementation. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(1):49–57. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302206.

Brownson RC, Eyler AA, Harris JK, Moore JB, Tabak RG. Getting the word out: new approaches for disseminating public health science. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(2):102–11. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000673.

Hirschhorn LR, Ramaswamy R, Devnani M, Wandersman A, Simpson LA, Garcia-Elorrio E. Research versus practice in quality improvement? Understanding how we can bridge the gap. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(suppl_1):24–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzy018.

McKay VR, Morshed AB, Brownson RC, Proctor EK, Prusaczyk B. Letting go: conceptualizing intervention de-implementation in public health and social service settings. Am J Community Psychol. 2018;62(1-2):189–202. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12258.

Kwon SC, Tandon SD, Islam N, Riley L, Trinh-Shevrin C. Applying a community-based participatory research framework to patient and family engagement in the development of patient-centered outcomes research and practice. Transl Behav Med. 2018;8(5):683–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibx026.

Pettibone KG, Balshaw DM, Dilworth C, et al. Expanding the concept of translational research: making a place for environmental health sciences. Environ Health Perspect. 2018;126(7):074501. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP3657.

Wathen CN, MacMillan HL. The role of integrated knowledge translation in intervention research. Prev Sci. 2018;19(3):319–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-015-0564-9.

Spiel C, Schober B, Strohmeier D. Implementing intervention research into public policy—the “I3-Approach”. Prev Sci. 2018;19(3):337–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0638-3.

Tait H, Williamson A. A literature review of knowledge translation and partnership research training programs for health researchers. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17(1):98. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0497-z.

Close GL, Kasper AM, Morton JP. From paper to podium: quantifying the translational potential of performance nutrition research. Sports Med. 2019;49(S1):25–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-018-1005-2.

Mazzucca S, Parks RG, Tabak RG, et al. Assessing organizational supports for evidence-based decision making in local public health departments in the United States: Development and psychometric properties of a new measure. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25(5):454–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000952.

Young BR, Leeks KD, Bish CL, et al. Community-university partnership characteristics for translation: evidence from CDC’s prevention research centers. Front Public Health. 2020;8:79. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00079.

Koh S, Lee M, Brotzman LE, Shelton RC. An orientation for new researchers to key domains, processes, and resources in implementation science. Transl Behav Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/iby095.

Barwick M, Dubrowski R, Petricca K. Knowledge translation: the rise of implementation: American Institutes for Research; 2020. p. 65. https://ktdrr.org/products/kt-implementation/KT-Implementation-508.pdf

Morgan J, Schwartz C, Ferlatte O, et al. Community-based participatory approaches to knowledge translation: HIV prevention case study of the investigaytors program. Arch Sex Behav. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01789-6.

Dzewaltowski DA, Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Estabrooks PA, Brock E. RE-AIM: evidence-based standards and a web resource to improve translation of research into practice. Ann Behav Med. 2004;28(2):75–80. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2802_1.

Pacheco CM, Daley SM, Brown T, Filippi M, Greiner KA, Daley CM. Moving forward: breaking the cycle of mistrust between American Indians and researchers. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):2152–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301480.

Geronimus AT, Thompson JP. To denigrate, ignore, or disrupt: racial inequality in health and the impact of a policy-induced breakdown of African American communities. Bois Rev Soc Sci Res Race. 2004;1(02). https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X04042031.

Gamble VN. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(11):1773–8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.87.11.1773.

Pirie A, Gute DM. Crossing the chasm of mistrust: collaborating with immigrant populations through community organizations and academic partners. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):2126–30. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301517.

Fernandez ME, Ruiter RAC, Markham CM, Kok G. Intervention mapping: theory- and evidence-based health promotion program planning: perspective and examples. Front Public Health. 2019;7:209. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00209.

Colquhoun HL, Letts LJ, Law MC, MacDermid JC, Missiuna CA. A scoping review of the use of theory in studies of knowledge translation. Can J Occup Ther. 2010;77(5):270–9. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2010.77.5.3.

Breimaier HE, Heckemann B, Halfens RJG, Lohrmann C. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): a useful theoretical framework for guiding and evaluating a guideline implementation process in a hospital-based nursing practice. BMC Nurs. 2015;14(1):43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-015-0088-4.

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research – technical assistance for users of the CFIR framework. CFIR. https://cfirguide.org/. Accessed 21 Feb 2022.

Hunter EL. Politics and public health—engaging the third rail. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22(5):436–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000446.

Glasgow RE, McKay HG, Piette JD, Reynolds KD. The RE-AIM framework for evaluating interventions: what can it tell us about approaches to chronic illness management? Patient Educ Couns. 2001;44(2):119–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(00)00186-5.

Stoll CRT, Izadi S, Fowler S, Green P, Suls J, Colditz GA. The value of a second reviewer for study selection in systematic reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2019;10(4):539–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1369.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number U48DP006401 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and, in part, by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01HL135220. Its content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MEW led the systematic review efforts and was a major contributor to manuscript writing efforts. SW assisted with the systematic review and was a major contributor to manuscript writing efforts. ZR assisted with the systematic review and provided substantial edits to manuscript drafts. DK engaged community advisors in as a last step in the systematic review and provided substantial edits to manuscript drafts. GTM critiqued systematic review methods, tested our resultant criteria, and was a major contributor to manuscript writing efforts. BWM was a major contributor to manuscript writing efforts. ATK was a major contributor to manuscript writing efforts. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wende, M.E., Wilcox, S., Rhodes, Z. et al. Developing criteria for research translation decision-making in community settings: a systematic review and thematic analysis informed by the Knowledge to Action Framework and community input. Implement Sci Commun 3, 76 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-022-00316-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-022-00316-z