Abstract

Background

Despite significant progress in the field of implementation science (IS), current training programs are inadequate to meet the global need, especially in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs). Even when training opportunities exist, there is a “knowledge-practice gap,” where implementation research findings are not useful to practitioners in a field designed to bridge that gap. This is a critical challenge in LMICs where complex public health issues must be addressed. This paper describes results from a formal assessment of learning needs, priority topics, and delivery methods for LMIC stakeholders.

Methods

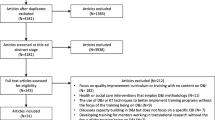

We first reviewed a sample of articles published recently in Implementation Science to identify IS stakeholders and assigned labels and definitions for groups with similar roles. We then employed a multi-step sampling approach and a random sampling strategy to recruit participants (n = 39) for a semi-structured interview that lasted 30–60 min. Stakeholders with inputs critical to developing training curricula were prioritized and selected for interviews. We created memos from audio-recorded interviews and used a deductively created codebook to conduct thematic analysis. We calculated kappa coefficients for each memo and used validation techniques to establish rigor including incorporating feedback from reviewers and member checking.

Results

Participants included program managers, researchers, and physicians working in over 20 countries, primarily LMICs. The majority had over 10 years of implementation experience but fewer than 5 years of IS experience. Three main themes emerged from the data, pertaining to past experience with IS, future IS training needs, and contextual issues. Most respondents (even with formal training) described their IS knowledge as basic or minimal. Preferences for future training were heterogeneous, but findings suggest that curricula must encompass a broader set of competencies than just IS, include mentorship/apprenticeship, and center the LMIC context.

Conclusion

While this work is the first systematic assessment of IS learning needs among LMIC stakeholders, findings reflect existing research in that current training opportunities may not meet the demand, trainings are too narrowly focused to meet the heterogeneous needs of stakeholders, and there is a need for a broader set of competencies that moves beyond only IS. Our research also demonstrates the timely and unique needs of developing appropriately scoped, accessible training and mentorship support within LMIC settings. Therefore, we propose the novel approach of intelligent swarming as a solution to help build IS capacity in LMICs through the lens of sustainability and equity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As the field of implementation science (IS) grows globally, interest in building researchers’, practitioners’, and policy makers’ capacity to engage in this work worldwide increases. Acknowledging this interest, the journal Implementation Science [1] solicited manuscripts describing training and curricula. Over the past few years, several articles have been published detailing training programs in the field, including two by some of the authors of this paper [2, 3]. A recent systematic review by Davis and D’Lima identified 41 capacity building initiatives (CBIs) in eight countries [4].

Despite significant progress, current training programs are inadequate to meet the global need, especially in low-and middle-income countries (LMIC) where many authors have acknowledged the urgent need for IS expertise to address complex, pressing public health issues [5,6,7,8]. In their systematic review, Davis and D’Lima pointed out that only 3 of the 41 studies were from relatively low-resource settings [4].

In response, various organizations have implemented training programs targeting LMIC participants in recent years. Examples are the University of North Carolina’s (UNC) partnership with Wits University in South Africa [9], the IS school at the annual conference of the Global Alliance for Communicable Diseases (GACD) [10], funding for capacity building provided by some National Institutes of Health (NIH) Institutes (e.g., the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) program on “Research Partnerships for Scaling Up Mental Health Interventions in Low-and Middle-Income Countries,” which requires capacity building activities in countries within the region but outside where the research is taking place), and various training programs sponsored by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Tropical Disease Research unit [11].

As programs such as these continue to grow, and as the need to train a wide variety of stakeholders expands, it becomes important to understand how well these programs align with the local contexts and needs of learners in LMIC settings. Context has been routinely acknowledged as a factor affecting outcomes in the IS literature [12, 13]. To develop appropriate and useful IS capacity building programs for LMIC settings, a formal assessment of learning needs, priority topics, and delivery methods for different stakeholders in these contexts is necessary. This study attempts to address this gap, drawing on our practical experience with running training programs.

In this paper, we describe the results from such an assessment designed to answer the following research questions:

-

1.

Who are the key stakeholders that need to learn/use IS methods in LMICs?

-

2.

What kind of IS content would be most useful to each stakeholder group, and what is the optimal delivery of that content?

-

3.

What are the implications for future research in IS capacity building in LMIC settings?

Our own impetus for this study was based on unpublished course evaluation data from various IS courses developed and taught by some of this paper’s authors in 2018 and 2020. For example, in 2020, a joint team from UNC and Wits University led a 2-day IS training course in Johannesburg for researchers and practitioners of HIV programs in South Africa. Formal course evaluations revealed significant heterogeneity in the perceptions of the material’s utility and relevance. Researchers felt it was superficial; practitioners found it too theoretical and difficult to apply concepts to their contexts. Moreover, many participants thought the course covered specialized topics when more foundational research skills were needed. Others felt that additional coaching and support were needed to help adapt and translate models, theories, frameworks, and strategies (unpublished observations).

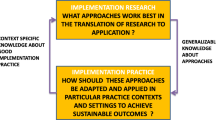

Based on these findings, we developed a conceptual “tiered” training model (Fig. 1) for IS in LMICs, published elsewhere [14]. This model is based on the premise that instructional systems must educate a large homogeneous population of learners on the basics of a field, with increasingly fewer specialists trained in progressively more complex problems. This model is commonly used in many contexts, such as education, where a general curriculum is offered to all students, with more intensive interventions targeting fewer students with specific needs and interests [15]. Our goal of this research was to assess the suitability of this model to LMIC training in IS settings, develop more precise definitions of the occupants of each of these tiers, create learning objectives for each tier, and identify areas for further research.

Methods

Stakeholder groups and definitions

To identify stakeholders for each tier, we first reviewed a sample of articles published in Implementation Science in the past 5 years (MWT). We purposively sampled additional articles on dissemination, implementation, and knowledge translation frameworks based on one author’s knowledge of the literature (RR). We included any person or entity the literature identified as having a role in any aspect of the implementation process. We aggregated stakeholders with similar roles and assigned a primary label and definition for each group, along with citations and examples (MWT). We sent the list by email to a purposive sample of twelve individuals known to one author (RR)—each recognized as experts based on their publication record and visibility in IS conferences—and requested them to review the table of stakeholders and identify gaps in the list or edit any definitions. Seven experts supplied extensive inputs, which we incorporated into a final stakeholder table (Table 1) (MWT). Three authors (MWT, RR, and CB) prioritized stakeholders from the list whose inputs would be most critical to develop learning curricula and training programs. The prioritization was based on our first research question, which was to identify stakeholders who could most immediately be potential candidates for IS training programs. These stakeholders (highlighted in Table 1) were those selected for interviews: senior government officials, organizational leaders, implementation researchers, clinical researchers, implementation specialists, staff managers, and implementers.

Interviewee selection and recruitment

We employed a multi-step sampling approach to recruit semi-structured interview participants, with the goal of approximating a random sample representing each IS stakeholder group. Our approach aimed to ensure the interviewees could demonstrate a connection to the field of IS, were based in or had extensive knowledge of LMIC settings, and were geographically diverse. Two authors (RS, AHM) provided introductions to key members of three global networks: Adolescent HIV IS Alliance (AHISA), GACD, and National Institutes of Mental Health-funded Hubs for Scaling Up Mental Health Interventions in LMICs. We emailed these contacts, with 7- and 14-day reminders, explaining the project and requesting a list of potential interviewees (MWT). The contacts sent back a list of names, or in some cases forwarded the invitation directly to their contacts; one person allowed the research team to post the invitation to a forum of 235 individuals in an online research community.

After assembling the list of potential participants, we individually emailed and sent 7-day reminders explaining the project and linking to a Google form, which we asked stakeholders to complete to indicate their interest in participation (MWT). The form also asked participants to select the IS stakeholder category that best described them. Once respondents filled enough forms for a random sampling strategy to be viable, we emailed one to three randomly selected participants from each stakeholder group to schedule an interview; we sent a reminder in 7 days. We conducted interviews simultaneously with ongoing recruitment using the same sampling process without replacement until reaching the target number of interviewees (five per stakeholder group) (MWT). During interviews, participants mentioned the dominance of English literature in the field. To explore whether there were significant differences in perceptions of learning needs of non-English speakers, we conducted preliminary interviews with one Spanish (MWT) and three French (MLE) speakers, aiming to recommend more detailed research in the future if necessary.

Data collection

The research team (MWT, RR) developed a semi-structured interview guide (Additional file 1) that we piloted and revised with two IS professionals and a doctoral student at UNC. The phone/video interviews lasted 30–60 min. We obtained verbal consent for and audio recorded each interview. We transcribed and translated French (NR) and Spanish interviews (MWT) verbatim so the analysis team could analyze interviews. For English interviews, the interviewer (MWT) took notes while interviewing, which two team members (MWT, SB) reviewed alongside the recording to clarify and add context to create “memos,” later used to elicit themes. Since most responses were in response to structured questions, this deductive approach to documentation captured the required level of detail while being efficient.

Data preparation

We used a multi-step process to create a deductive codebook to analyze the memos. We created the initial codebook deductively from the interview guide (MWT). Three authors (MWT, SB, CB) used this version to code one randomly selected interview together to finalize the codebook. Next, to establish intercoder reliability [27], two authors (MWT, SB) coded a randomly selected 25% of the memos individually using NVivo 12 software. We calculated the kappa coefficient for each memo, and the team met to refine the coding process before proceeding to the next memo if the coefficient was less than 0.6—indicating good agreement [28]. Because the kappa values of the first six memos were each greater than 0.8 (indicating excellent agreement), we terminated this step and randomly coded remaining memos independently (MWT, SB).

Data validation

Validation techniques are recommended to establish trustworthiness of qualitative studies [27]. Techniques include credibility (fit between respondent views and researcher interpretation), transferability (generalizability of results), dependability (research process is logical and clearly documented), and confirmability (conclusions clearly stem from the data) [29, 30]. Our systematic, rigorous approach to coding lent confidence to our dependability.

For confirmability, our data analysis must accurately capture the context of interviewee comments. Therefore, we conducted an internal reflection based on the concept of double loop learning [25]. Double loop learning is intended to address dissonance between tacit assumptions based on mental models that individuals use to make decisions, and the theories individuals articulate as their basis for decision-making. To reduce the influence of our own assumptions and capture the interviewees’ context, two authors (EA, RR) created a rubric adapted from a reflective method called the Critical Moments Technique [31] (Additional file 2). The main interviewer (MWT) used this rubric to identify critical moments from each interview that uniquely described interviewees’ contexts, and to confirm these moments had been included in coding and interpretation.

For credibility and transferability, we sought to guard against implicit bias [32] in data interpretation that could arise from the study team’s location in a HIC. We adapted our validation approach from member checking [33], which involves returning data or results to interviewees to ensure the interview’s intent has been accurately captured. We purposively selected two interviewees and two other individuals who collectively brought a broad range of implementation research, practice, and policy experience from Africa and Asia. We requested that they holistically review our results and the assumptions underlying our interpretation of the data to provide an independent assessment of the contextual credibility of our findings and their generalizability to LMICs. We incorporated feedback from these reviewers to refine our results.

Data analysis

Concordance analysis

For the first research question, we (MWT, RR, CB) performed a concordance analysis between the interviewees’ self-classification of their roles and the interviewer’s classification based on the definitions in Table 1.

Thematic analysis

For the second research question, we used thematic analysis [26] to identify patterns from qualitative data. In further elaborations of the method, a distinction is made between “codebook” and “reflexive” approaches to thematic analysis. In the codebook approach, themes are pre-determined by codes derived from interview questions. Themes therefore are both inputs and outputs of the analysis process. In the reflexive approach, coding is open ended, and the themes reflect the analysis output [34]. We primarily followed a codebook approach, though we refined our findings by our internal reflection and external reviewer feedback. This combination of methods assured rigor in the trustworthiness of the data while being sensitive to context. As Braun and Clarke state, “overall, what is important is that researchers use the approach to TA [thematic analysis] that is most appropriate for their research, they use it in a ‘knowing’ way, they aim to be thoughtful in their data collection and analytic processes and practices, and they produce an overall coherent piece of work” ([31], p. 7). Our analysis approach reflects this philosophy.

We followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist [35] (Additional file 3) to guide documentation of methods and results.

Results

Interviewee characteristics

Participants worked in over 20 countries spanning Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East, with most also living in their countries of work (Table 2). A few were currently associated with HICs (e.g., Canada, Japan), but their primary work experience had been in LMICs. Most of the participants who mentioned their prior professional experience had a medical degree or other post-graduate training. Many were responsible for program management or coordination, followed by researchers/academics, physicians, and health financing professionals. The majority had over 10 years of implementation experience but fewer than 5 years of experience in IS.

Concordance analysis results

The concordance analysis explored how interviewees perceived their role within the field of IS and how our team classified them based on the description of their work during the interview. The self-reported stakeholder category and the interviewer assigned category differed among 28% of interviewees (11 of 28). This discordance was because interviewees played multiple roles within their organizations and throughout their careers. The greatest discordance was among two groups. The first was interviewees who classified themselves as clinical researchers or implementers whom we classified as implementation researchers. The reason for this discordance was that we distinguished those who said they focused on developing clinical interventions from those who worked on creating and testing implementation strategies. However, these distinctions were blurred for the interviewees. In addition, some clinical researchers also classified themselves as implementers because they provided services while simultaneously engaged in research. The second group involved those who classified themselves as implementers. We differentiated between those who managed implementation projects (staff managers) and those responsible for the implementation (implementers), but the interviewees did not always make this distinction.

Overall, our interviewees described themselves as “implementers” if they were involved in any aspect of the implementation process. Our interviews revealed heterogeneity in roles, training experience, and stated learning needs that led to more nuanced classifications that can assist in the development of customized and targeted training programs.

Thematic analysis results

Themes are described in three major categories: experience with IS training, future training needs, and crosscutting contextual issues. The first two themes align directly with interview questions, consistent with the codebook approach to thematic analysis described above. These themes highlight majority perspectives. The third theme arose from our internal reflections and external validation inputs and emphasizes salient learning considerations beyond IS training.

Experience with IS training

Table 3 summarizes the perception of IS training interviewees had received to date. About half the stakeholders had no formal IS training; others mostly participated in IS trainings as opportunities arose, for example through workshops or short courses. A few had pursued IS graduate training programs. Modalities through which the interviewees had acquired IS knowledge varied widely, including online resources, online courses, textbooks, self-study, collaborative learning or alliances, and conferences.

Most interviewees described their training experiences as positive, saying, for example, that trainings helped them understand what IS is and learn new approaches to research or job duties. However, many struggled to define IS. Seventy-five percent of respondents defined IS as (a) closing the research-to-practice gap in implementing programs or interventions or (b) studying/applying scientific methods to design, implement, and scale programs. For example, one interviewee stated:

“Putting research into practice but doing it in an evidence-based manner. You don’t just translate your findings into practice and ask people to just apply it, but you do it in a way that you make sure to monitor the process and evaluate each step, looking at what goes wrong or right and how to incorporate this in a way that can be scaled up.” -Clinical researcher

This definition is consistent with the responses to how IS is primarily applied. Two thirds of interviewees stated that they used IS for evaluation of implementation efforts or designing and adapting new programs. Fifteen percent indicated using IS to influence policy. Overall, even among researchers, the understanding of IS appeared more akin to operational research and process evaluation (e.g., to understand barriers to implementation within a specific program). Only five respondents described using IS to frame or guide implementation research activities, and five were unable to describe how IS applied to their work.

When asked about use of IS theories, models, and frameworks, almost 40% of interviewees reported not using or were not able to identify any IS frameworks or tools. Fewer than ten stakeholders named any IS-specific models, theories, or frameworks. Eleven mentioned using evaluation frameworks, though with the exception of RE-AIM [36], those mentioned were generic, such as theory of change and logic models. This finding reinforces our prior result that there is confusion between IS and process evaluation. Four respondents described CFIR (Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research) [37], one person mentioned EPIS (Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment) [38], and two generically described process frameworks.

Even respondents who had undergone formal training in IS mostly described their IS understanding of the field as basic or minimal. The stakeholders named several gaps in training, the most common (40%) being difficulty in applying IS principles to their work and not knowing how to convey IS to other stakeholders. In the words of one interviewee:

“I think there is a gap in understanding how IS can be integrated into each program to enhance the way it works. Very often, there is so much research out of which recommendations emanate, but there is not always guidance on how to implement those recommendations. There is a gap in knowledge of how do you translate those research outcomes into something meaningful on the ground.” -Organizational leader

Most of the other gaps mentioned involved foundational capacity not directly related to IS, such as proposal writing, research designs, or data visualization. Generic barriers to filling these training gaps such as language, time, training locations, training fees, and lack of access to experts were mentioned, but nothing was unique to IS training. In summary, most respondents appeared to view the IS training that they had received as part of general capacity building in program implementation and evaluation rather than as skills in a separate discipline. One interviewee stated:

“In the design of all projects, there is an inclusion of some sort of evaluation of how things are implemented. You include measures of how processes are going out, they use outcomes, outputs, and activities frameworks.” -Implementation specialist

Future IS training needs

Table 4 summarizes interviewees’ stated requirements for an ideal IS training program. Reflecting the variation in individual training experience, there was significant heterogeneity in respondent opinions of who should be trained, who should train, how training should be conducted, and the topics that should be covered. However, amidst this variation, some common themes emerged.

A majority of respondents emphasized the need for IS topics to cover basic, practical topics. The top six topics that stakeholders felt should be covered were basic IS knowledge [14], practical application of IS [10], application to LMIC contexts [6], engaging stakeholders [6], integrating IS into program planning and evaluation [6], and IS research methods, grant writing, and dissemination [6].

A significant majority of respondents (70%) preferred a combination of online and in-person training. Many interviewees described the need for interactive training programs including elements such as workshops, training embedded in fieldwork, peer learning, and interactive online discussion. There were also suggestions that the training duration should be linked to the distribution of time spent online and face to face. As one interviewee suggested,

“If it’s in person, then a shorter course. In person is much better. If online, then a bit longer. With online courses, not being able to engage that well is a gap.” -Clinical researcher

Twenty-three of 39 (59%) respondents expressed the need for an interdisciplinary team of trainers. An equal number mentioned the need for trainers to have practical experience, with a subset (17%) expressing a preference for trainers who were comfortable with both theory and practice. In addition, some stakeholders specifically stated that instructors should have experience working in LMICs rather than only having training from Western knowledge, and that IS training topics should include application of IS in specific contexts such as LMICs. As one interviewee mentioned,

“I recently went to an implementation science training…by someone from the UK. There was a bit of discussion after that there was some disconnect between the overly-theoretically driven approach by the lecturer and the actual needs in African contexts. So you need more than an implementation science researcher from North—you need someone working in the African context as well.” -Implementation researcher

Sixty-five percent of respondents emphasized the need for training programs to include or be supplemented by mentorship or apprenticeship either during or following training. Other ideas for ongoing support were also mentioned frequently, the most common being communities of practice or learning networks and monthly seminars or other structured events. There was an overall sentiment that training alone cannot build the skills needed to take IS principles from theory to practice. In the words of one respondent,

“Current programs place so much emphasis on the theories and frameworks, but little emphasis on mentorship. Beyond being a science, implementation is also an art. Transferring knowledge within the arts involves lots of learnings which are informal.” -Implementation researcher

Crosscutting contextual issues

Several interviewees did not distinguish between implementation research topics and basic research topics. When asked about gaps in their IS knowledge and desire for future training, many stakeholders listed skills and topics related more to general research than to implementation research. Some of the topics suggested were as follows: retrospective reflection to determine program impact, proposal writing, evaluating literature and evidence, designing research studies, data visualization, analysis, evaluation, project management, and use of statistical software.

Similarly, some interviewees stated that applying implementation research was difficult in their countries because basic research capacity was lacking. The ability to conduct implementation research assumes foundational research methods knowledge, and many interviewees described the need to build these skills first or in conjunction with implementation research capacity. In the words of one interviewee:

“Research capacity and output [in my country] is low...so we are just struggling to do basic research—to do operational research. We haven’t been able to move from actually applying research to improving public health. So it is a difficult thing to do IS.” -Implementer

In addition, some interviewees found the emphasis on implementation research training premature when there is still a critical need to develop evidence appropriate to LMICs. Several stakeholders felt that much of the evidence is developed in HICs rather than LMICs, and that interventions are “imported.” For example, many stakeholders worked on projects addressing HIV and/or tuberculosis (TB). The prevalence and impact of HIV and TB in Southern Africa is considerably different than in HICs. As one interviewee stated:

“The evidence is developed in HICs, but LMICs don’t have the baseline data even of the current status and need. I think that first we must generate that evidence, and then we will need to use IS knowledge to scale up.” -Implementer

Interviewees also described how funding structures made conducting and applying IS research a challenge in their countries. In some cases, project funding that came from HICs placed constraints on implementers’ local decision-making authority, optimal measurement, and sustainability of projects. One mentioned that the US-funded project she worked on was “highly prescriptive and mandated by the US,” and two others spoke to the pressure in their US-funded projects to “do things fast,” and measure indicators that impede implementation rather than advance it to targets set by the donor. Another described donors’ impediment to project sustainability:

“So much of the work is donor-driven and therefore finite. At the end of the project cycle, the partner changes…The big development partners like [US funder] have capacity to absorb outputs [referring to IS research], but so much is done by community organizations. How can we involve those partners and capacitate there?” -Organizational leader

Finally, five stakeholders mentioned language as a barrier to learning IS and/or spreading IS knowledge in their countries, pointing out that the vast majority of IS literature is written in English and that, “even the very definition of ‘implementation science’ is purely in English.” A French-speaking interviewee mentioned the lack of IS training materials available in French:

“When I started my master’s in English, I found it extremely challenging to access resources, to read and understand them to differentiate one approach from the other. For the French-speaking world, it’s the fact that training materials and resources in implementation science are unavailable.” -Implementation researcher

Further, the French-speaking interviewees reported that IS is not widely known as a science itself and that some stakeholders involved in IS are not fully aware that they are doing IS work.

Discussion

Alignment with existing IS literature

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic assessment of IS learning needs of LMIC stakeholders. Our results reinforce findings from other researchers on training needs and competencies, many of which are not unique to our setting. We will first discuss how our findings reflect training challenges in all contexts and then highlight the unique issues identified by our stakeholders as a rationale for our suggested capacity building approach.

Unmet need for IS capacity

Our findings reinforce the enormous demand for IS global capacity and the need to develop approaches to train at scale. Our interviewees reported that they took advantage of every opportunity they could find to be trained. Chambers and Proctor [39], in their summary of the meeting convened by the NIH in 2013 focusing on training in dissemination and implementation (D&I), acknowledged that a broader approach to training is needed than is currently available. Some salient recommendations by the attendees for improving D&I training were to increase training duration, review and update training content, employ train-the-trainer models, and build support networks for training program alumni [39]. The systematic review by Davis and D’Lima reports that many of the current IS training opportunities, such as the NIH-funded training institutes, are extremely competitive and therefore are unable to meet the demand. They also report that conferences and meetings such as the annual NIH conference on the Science of D&I, Society for Implementation Research Collaboration, the Global Implementation Conference, or the Australian Implementation Conference are oversubscribed. Our interviewee sample was composed of those who belonged to various international networks, and they were fortunate enough to have access [4]. There are likely a large number of other researchers and practitioners who are interested but unable to gain access to IS training programs.

Targeted training for different stakeholder groups

Our interviewees played a variety of implementation-related roles, emphasizing the need for multiple training programs to meet heterogeneous needs. This finding is aligned with similar observations by other authors. Davis and D’Lima state that many of the capacity building interventions in their systematic review are focused on those who are already experienced researchers, and they identify the need for more novices in the field [4]. Albers, Metz, and Burke propose developing the competencies of “Implementation Support Practitioners” who assist and coach service providers and organizational leaders in implementing evidence-based interventions and practices [40]. Furthermore, Leppin et al. describe the “Teaching for Implementation” framework to train both researchers and practitioners. The interviewees in our study included novices and experts, researchers and practitioners, implementers, and support specialists, who all require thoughtfully designed, targeted training programs [41].

Need for a broad set of competencies

Our research has reinforced the need for training curricula that encompass a broader set of competencies than just IS. This finding has also been identified in other research [18, 42, 43]. Metz et al. identified 15 competences for Implementation Support Practitioners across three domains. Applying IS frameworks and strategies is only one of these competencies. Others range from building relationships, to facilitation, to developing teams, to addressing power differentials [18]. In LMIC settings, the WHO collaborated with a consortium of global universities to create a framework of core competencies for implementation research. The framework comprises 59 competencies in 11 domains spanning a broad set of disciplines. Similar to the list of competencies developed by Metz et al., skills in scientific inquiry (e.g., research question formulation, research design, knowledge of IS theories, models, frameworks) that are the focus of IS courses are not central to these competencies. The central component of the WHO training framework is learning how to “identify appropriate stakeholders, engage with them meaningfully, form robust collaborations and implement change via these collaborations throughout the IR process” [19]. Our findings support the need for an IS training model to teach many topics from a broad set of competencies to a wide audience, rather than a specific set of topics taught in depth to a few.

Interactive support

A majority of our interviewees acknowledged the critical importance of what Darnell et al. [44] call “interactive resources” such as workshops, conferences, and mentorships and commented on the difficulty of finding suitable mentors. These results are aligned with the evidence illustrating the value of mentoring to foster research collaborations [45] or to facilitate learning on the application of IS concepts, theories, and frameworks [46], as well as with findings from a content analysis of 42 D&I resources that found that mentoring, networking, and technical assistance were the least common forms of available interactive resources [44].

Application to LMIC settings

The fact that many of our findings related to the learning needs of IS stakeholders in LMICs have also been reported in the literature focusing on high-resource contexts does not imply that the situation across these contexts is identical. While the issues may be similar, interpretation and strategies to address them must be different for our interviewees for two reasons. The first reason is the question of scale. The gap in training capacity relative to the demand, the range and scope of training that is required, and the effort needed to develop a pool of qualified local mentors with knowledge of culture, customs, and language in various geographies is significantly greater in LMIC settings.

The second consideration is structural and has to do with the way in which the participants in our interviews gained access to training. As our concordance analysis showed, our “stakeholder groups” were not stable, homogeneous entities. At various times in their careers, professionals can be researchers, practitioners, policy makers, or organizational leaders, sometimes simultaneously. Stakeholders may identify themselves as belonging to a particular group, even if their roles and activities make them more likely to be classified differently. This is in part because many of our stakeholders build their professional careers by working on a variety of research or program implementation projects dictated by the availability of Western grant funding. Depending on what was needed for the purposes of the project, our interviewees demonstrated an impressive ability to be flexible and play different roles. However, this flexibility comes at a cost because it could be a barrier to achieving sustained expertise.

We found that this mobility across projects also resulted in fragmented access to training opportunities. Many of our interviewees acquired their skills opportunistically, determined by the training that was available to them as a consequence of working on a project. This need to take advantage of whatever training is available results in a patchwork of competencies with some areas of strength and other critical areas in which there are substantial gaps. Moreover, because different individuals attend different training programs, there is no infrastructure for creating the cohesive ongoing learning communities similar to those that are available in the US to Implementation Research Institute (IRI) or Training Institute for D&I Research in Health (TIDIRH) fellows to advance their skills and expertise [45, 47].

Finally, most of our interviewees participated in training opportunities that were led by instructors or used content from high-income settings and were primarily delivered in English. “Context matters” is a core tenet of IS (e.g., [13, 48]), but context-appropriate training is hard to come by. Many interviewees expressed the need for trainers and mentors who had knowledge and experience of local issues and were able to bring local examples to their teaching.

These structural factors reflect the disparities in how funding for programs is generated, where expertise is located, and how leadership is distributed, not just in IS, but in global health in general. Recent writing by Abimbola (2019) addressing power imbalances in authorship [49] and content of global health articles and by Baumann and Cabassa (2020) and Snell-Rood (2021) on the need for IS theories, models, and frameworks to address inequities and power differentials has drawn attention to these issues [50, 51]. While a concentrated focus on these issues is critical, it is important to mention that our interviewees did not frame their responses through the lens of colonialism or power differentials, but presented their learning needs as a pragmatic problem for which solutions are needed. It is in this context that we propose the ideas that follow.

Imagining new learning models

The heterogeneity in current capability, the breadth of competencies required, the scale at which capacity needs to be built, and the critical need for context-appropriate learning revealed in our interviews suggest that traditional classroom-based training models are likely to be of limited value. Rather, there is the need for what Eboreime and Banke-Thomas call the “art and craft” of implementation training, that emphasizes “relationships, supportive supervision and coaching” [52]. Our findings suggest the need for a learning approach that builds upon individual participants’ existing strengths and knowledge, facilitates generation of context-specific IS knowledge, and is taught in an interactive format, with mentoring as an integral component. Situational learning theory [53] may serve as a useful frame for developing a learning model. Situational theory states that learners progress from novice to expert through engagement in communities of practice where learning opportunities arise through social interactions with others involved in the same pursuit. Rather than primarily investing in classroom training, where an external expert delivers a body of content that may not be relevant or useful, a promising approach might be to create learning networks focused on implementation research, practice, or policy. Facilitator teams with IS knowledge and understanding of the local context would mentor participants in systematic approaches to test, adapt, or create locally relevant implementation frameworks, tools, and strategies. These networks would be different from the global networks such as GACD or AHISA in that they would intentionally focus on a local region or geography, explicitly recruit an interdisciplinary team of advisors who combine technical IS knowledge with a deep understanding of context and promote learning through a variety of relationships (e.g., apprentice/expert, peer-to-peer, mentored groups) that emphasize practice. To our knowledge, these types of networks do not exist today in LMICs.

Wenger defines three necessary characteristics for a community of practice: (1) the domain—the shared area of competence that the learners seek to advance; (2) the community—the intentional group of learners committed to relationships to further learning; and (3) the practice—the collection of activities, processes, and interactions through which learning occurs [54]. Learning networks based on these characteristics may be attractive models when there is agreement about the domain. But our interview results revealed significant variation in background and knowledge even within the domain of IS, and also wide differences in learning priorities. As mentioned earlier, the WHO core competency framework for implementation research in LMICs [19] identifies 11 domains ranging from engaging stakeholders, to conducting ethical research, to research designs—each an area around which a learning network can form. A single model to facilitate learning of IS seems unlikely to meet the diversity of need. Our findings suggest that dynamic models that bring situational learning to the individual level by providing customized, adaptive, and agile learning environments still rooted in mentoring, relationships, and practice are necessary. Rather than establishing a predefined body of knowledge and a rigid instructional structure, the learning process and the learning support would emerge from the scope and complexity of the need.

Drawing from the service sector: directions for future research

An idea for a dynamic support model, called intelligent swarming℠ [55], has been proposed in the technology industry as a way to provide more responsive, timely, and customized technical support. Drawing from the principles of agile software development, intelligent swarming replaces the traditional process of referring customers from generalist to experts with handoffs at each level, with a collaborative “swarm” of support personnel who best match the customer’s unique needs and are motivated and capable of providing the necessary assistance. For simple problems, the swarm could be a single person; for more complex problems, the customer is at the center of an interdisciplinary network of helpers that could include technical support staff, sales teams, strategic partners, or other customers. The approach is based on the principles listed in Fig. 2. It is instructive to speculate how such a model might work to meet the diverse learning needs of LMIC stakeholders. Figure 3 shows a network of support resources who could constitute a swarm.

One of the critical features of the swarm that makes it dynamic and adaptive is the matching process. This could be manual or automated, but the success of the swarm model will depend on the matchmaker’s ability to quickly assess, identify, and assemble the particular support team that meets the learning need. Depending on the need, this could be as simple as referral to relevant literature or instructional modules. For more complicated requests, such as the need to understand the use of a particular framework, the swarm may include networks of peers who have experience with the framework in various settings or consultation with local experts. For assistance with an implementation research proposal, the swarm might include implementation scientists, researchers, and program implementers with contextual knowledge about the setting. For policy makers seeking to use research data for decision-making, the swarm might include researchers, government personnel responsible for managing implementation, and frontline staff responsible for delivery. The learners themselves may be both customers of the swarm and suppliers, and willingness to contribute to the swarm might be imposed as a necessary precondition for access to resources. The swarm model may not always be a replacement for traditional training but may be a translational supplement to facilitate knowledge use. Initially, when local capacity in a particular setting is scarce, the networks from which swarms can be assembled might need to be global, and swarms must be carefully assembled to balance external expertise with local experience.

Intelligent swarming is still untested in these contexts and would need the infrastructure, incentives, and local capacity to make these models a reality. But we strongly believe that an emergent, adaptive approach is a powerful and innovative way to accommodate the enormous heterogeneity in background and skills among those involved in implementation-related activities in LMICs and to meet the enormous demand for capacity building in the field. We advocate for increased research efforts to develop and test swarming models for learning. As increasing numbers of local researchers and practitioners gain competency in key IS domains, learning networks with deeply rooted context-specific expertise can be developed, resulting in the availability of an equitable and appropriate body of implementation research knowledge closest to where it is most needed.

Limitations

Although we employed a strategy meant to approximate a representative sample of each stakeholder group, misrepresentation could have skewed the results. Additionally, our positionality as researchers based in a HIC researching the learning needs of stakeholders in LMICs may have biased our methods and findings. However, we made several attempts to limit bias (e.g., member checking, critical moments rubric).

Conclusions

This work is the first to explicitly explore and highlight the need for fundamental, widespread, and context-specific IS training and capacity building in conducting basic operational research for key stakeholders in LMICs. While many of the learning needs expressed by our interviewees are also issues in high-income settings, the scale of the gap between demand and existing capacity, the complex factors affecting access and availability, and the variation in expertise resulting from HIC initiated funding streams create a compelling case for innovative approaches that have not been tested before. We propose the novel approach of intelligent swarming as a solution to build IS capacity in LMICs through the lens of sustainability and equity.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AHISA:

-

Adolescent HIV Implementation Science Alliance

- D&I:

-

Dissemination and implementation

- GACD:

-

Global Alliance for Communicable Diseases

- HIC:

-

High-income countries

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IS:

-

Implementation science

- LMIC:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- NIH:

-

National Institutes of Health

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

References

Straus SE, Sales A, Wensing M, Michie S, Kent B, Foy R. Education and training for implementation science: our interest in manuscripts describing education and training materials. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):1–4 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0326-x.

Ramaswamy R, Mosnier J, Reed K, Powell BJ, Schenck AP. Building capacity for Public Health 3.0: introducing implementation science into an MPH curriculum 13. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):1–10.

Ramaswamy R, Chirwa T, Salisbury K, Ncayiyana J, Ibisomi L, Rispel L, et al. Developing a field of study in implementation science for the Africa Region: the Wits–UNC AIDS Implementation Science Fogarty D43. Pedagog Heal Promot. 2020;6(1):46–55.

Davis R, D’Lima D. Building capacity in dissemination and implementation science: a systematic review of the academic literature on teaching and training initiatives. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):1–26.

Ridde V. Need for more and better implementation science in global health. BMJ Glob Heal. 2016;1(2):1–3.

Peterson HB, Haidar J, Fixsen D, Ramaswamy R, Weiner BJ, Leatherman S. Implementing innovations in global women’s, children’s, and adolescents’ health: Realizing the potential for implementation science. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(3):423–30.

Theobald S, Brandes N, Gyapong M, El-Saharty S, Proctor E, Diaz T, et al. Implementation research: new imperatives and opportunities in global health. Lancet. 2018;392(10160):2214–28 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32205-0.

El-Sadr WM, Philip NM, Justman J. Letting HIV Transform Academia — Embracing Implementation Science. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(18):1679–81 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1314777.

Wits-UNC Partnership: expanding capacity in HIV implementation science in South Africa [Internet]. 2015. [cited 2021 Mar 23]. Available from: https://grantome.com/grant/NIH/D43-TW009774-07.

GACD Annual Scientific Meeting 2020 [Internet]. 2021. [cited 2021 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.gacd.org/research/research-network/gacd-annual-scientific-meeting-2020.

Training and Fellowships [Internet]. World Health Organization Tropical Disease Reasearch. 2021. [cited 2021 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.who.int/tdr/capacity/strengthening/en/.

Nilsen P, Bernhardsson S. Context matters in implementation science: a scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–21.

Bergström A, Skeen S, Duc DM, Blandon EZ, Estabrooks C, Gustavsson P, et al. Health system context and implementation of evidence-based practices-development and validation of the Context Assessment for Community Health (COACH) tool for low- and middle-income settings. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1) Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0305-2.

Ramaswamy R, Powell BJ. A tiered training model to build system wide capacity in implementation science - current learning and future research. In: Proceedings from the 11th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation; 2018 December 3-5; Washington, DC. Place of publication: Implementation Science; 2019. Available from: https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-019-0878-2.

Hallahan DP, Kauffman JM, Pullen PC. Exceptional learners: an introduction to special education. 13th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson; 2014.

Raghavan R. The role of economic evaluation in dissemination and implementation research. In: Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice, Second Edition. Oxford University Press; 2017.

Metz A, Louison L, Ward C, Burke K. Implementation specialist practice profile: skills and competencies for implementation practitioners; 2018.

Metz A, Louison L, Burke K, Albers B, Ward C. Implementation support practitioner profile guiding principles and core competencies for implementation practice [Internet], vol. 4.0. Chapel Hill; 2020. Available from: https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/sites/nirn.fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/ISPractice Profile-single page printing-v10-November 2020.pdf

Alonge O, Rao A, Kalbarczyk A, Maher D, Gonzalez Marulanda ER, Sarker M, et al. Developing a framework of core competencies in implementation research for low/middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Heal. 2019;4(5) Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/content/4/5/e001747.

Nabyonga Orem J, Marchal B, Mafigiri D, Ssengooba F, Macq J, Da Silveira VC, et al. Perspectives on the role of stakeholders in knowledge translation in health policy development in Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):1–13.

Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, Carpenter CR, Griffey RT, Bunger AC, et al. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69(2):123–57.

Aarons GA, Moullin J, Ehrhard M. The role of organizational processes in dissemination and implementation research. In: Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice; 2017.

Birken S, Clary A, Tabriz AA, Turner K, Meza R, Zizzi A, et al. Middle managers’ role in implementing evidence-based practices in healthcare: A systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):1–15.

Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, Noonan R, Lubell K, Stillman L, et al. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: The interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3–4):171–81.

Argyris C, Schon DA. Theory in practice: increasing professional effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1974.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101 Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Macphail C, Khoza N, Abler L, Ranganathan M. Process guidelines for establishing intercoder reliability in qualitative studies. Qual Res. 2015:1–15.

Burla L, Knierim B, Barth J, Liewald K, Duetz M, Abel T. From text to codings: Intercoder reliability assessment in qualitative content analysis. Nurs Res. 2008;57(2):113–7.

Forero R, Nahidi S, De Costa J, Mohsin M, Fitzgerald G, Gibson N, et al. Application of four-dimension criteria to assess rigour of qualitative research in emergency medicine. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–11.

Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):120–4.

McDowell C, Nagel A, Williams SM, Canepa C. Building knowledge from the practice of local communities. Knowl Manag Dev J. 2005;1(3):30–40 Available from: http://journal.km4dev.org/index.php/km4dj/article/view/44.

Payne BK, Vuletich HA. Policy insights from advances in implicit bias research. Policy Insights Behav Brain Sci. 2018;5(1):49–56 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732217746190.

Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F. Member checking: a tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1802–11.

Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Terry G. Thematic analysis. Handb Res Methods Heal Soc Sci. 2018:1–18.

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9) Available from: https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2014/09000/Standards_for_Reporting_Qualitative_Research__A.21.aspx.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–7 Available from: http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):1–15.

Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SMC. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res. 2011;38(1):4–23.

Proctor EK, Chambers DA. Training in dissemination and implementation research: a field-wide perspective. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(3):624–35 Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27142266.

Albers B, Metz A, Burke K. Implementation support practitioners- a proposal for consolidating a diverse evidence base. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–10.

Leppin AL, Baumann AA, Fernandez ME, Rudd BN, Stevens KR, Warner DO, et al. Teaching for implementation: A framework for building implementation research and practice capacity within the translational science workforce. J Clin Transl Sci. 2021;5(1):1–7.

Tabak RG, Padek MM, Kerner JF, Stange KC, Proctor EK, Dobbins MJ, et al. Dissemination and implementation science training needs: insights from practitioners and researchers. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(3):S322–9 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.10.005.

Schultes MT, Aijaz M, Klug J, Fixsen DL. Competences for implementation science: what trainees need to learn and where they learn it. Adv Heal Sci Educ. 2020;26(1):19–35 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-09969-8.

Darnell D, Dorsey CN, Melvin A, Chi J, Lyon AR, Lewis CC. A content analysis of dissemination and implementation science resource initiatives: what types of resources do they offer to advance the field? Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):1–15.

Luke DA, Baumann AA, Carothers BJ, Landsverk J, Proctor EK. Forging a link between mentoring and collaboration: a new training model for implementation science. Implement Sci 2016;11(1):1–12. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0499-y

Jacob RR, Gacad A, Pfund C, Padek M, Chambers DA, Kerner JF, et al. The “secret sauce” for a mentored training program: qualitative perspectives of trainees in implementation research for cancer control. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–11.

Vinson CA, Clyne M, Cardoza N, Emmons KM. Building capacity: a cross-sectional evaluation of the US Training Institute for Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):1–6.

Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3–4):327–50.

Abimbola S. The foreign gaze: authorship in academic global health. BMJ Glob Heal. 2019;4(5) Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/content/4/5/e002068.

Baumann AA, Cabassa LJ. Reframing implementation science to address inequities in healthcare delivery. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–9.

Snell-Rood C, Jaramillo ET, Hamilton AB, Raskin SE, Nicosia FM, Willging C. Advancing health equity through a theoretically critical implementation science. Transl Behav Med. 2021;11(8):1617–25.

Eboreime EA, Banke-Thomas A. Beyond the science: advancing the “art and craft” of implementation in the training and practice of global health. Int J Heal Policy Manag. 2020;x:1–5.

Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. New York and Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1991.

Wenger E. Communities of practice: learning, meaning, and identity: Cambridge University Press; 1999.

Consortium for Service Innovation. Intelligent swarming [Internet]. [cited 2021 Mar 23]. Available from: https://library.serviceinnovation.org/Intelligent_Swarming.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the 39 interviewees who volunteered their time and insights to this study, and to two of the interviewees for member-checking the results. We appreciate Drs. Latifat Ibisomi and Malabika Sarker for their external review of the results. Finally, thanks to Andrea Mendoza for assistance translating English materials to Spanish.

Funding

This study was funded by NIH Fogarty International Center Grant D43TW009774 University of North Carolina/University of the Wits Waters Rand AIDS Implementation Research and Cohort Analyses Training Grant. AP and RR are co-PIs, KS is the program manager, and MWT was funded as a graduate research assistant to conduct the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RR, AHM, RS, and KS conceived of the study. MWT, RR, and CB designed the study protocol and wrote the interview guide. MWT acquired IRB approval; conducted the literature review and concordance analysis; defined stakeholder groups; recruited participants with assistance from RR, AHM, RS, AP; interviewed English- and Spanish-speaking participants; and transcribed and translated Spanish interview materials. MLE recruited and interviewed French-speaking participants and transcribed French interview results. NR completed French translations of recruitment materials, the interview guide, and transcripts. MWT and SB wrote and coded memos of English interviews. MWT, SB, EA, CB, and RR analyzed results and wrote the manuscript. EA and RR developed the data validation protocol. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board deemed this research exempt.

Consent for publication

No identifiable individual data is presented in this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Interview Guide.

Additional file 2.

Critical Moments Rubric.

Additional file 3.

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Turner, M.W., Bogdewic, S., Agha, E. et al. Learning needs assessment for multi-stakeholder implementation science training in LMIC settings: findings and recommendations. Implement Sci Commun 2, 134 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00238-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00238-2