Abstract

Background

This is a secondary analysis of prospectively acquired data approved by the hospital institutional board committee. We performed a retrospective chart review of 463 patients who underwent a CT Chest for suspected COVID-19 infection between April 1st, 2020, and March 31st, 2021. Patients were grouped based on the CT chest obtained protocol: ultra-low dose or full dose. The likelihood of suspicion of COVID-19 infection was classified on a Likert scale based on the probability of pulmonary involvement. For each group, the sensitivity and specificity of CT were compared to nasopharyngeal swab as standard of reference. The median dose length product and duration of apnea were compared between both groups using two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. The aim of this study is to share our experience of reducing radiation dose in COVID-19 patients by using an ultra-low dose CT chest protocol on a 16 row multidetector CT scan in a hospital with limited resources.

Results

Two hundred sixty-nine patients underwent a full dose CT and 194 patients an ultra-low dose CT. In the former group, the median dose length product was 341.11 mGy*cm [Interquartile range (IQR), 239.1–443.2] and the median duration of apnea was 13.29 s [IQR, 10.85–15.73]. In the latter group, the median dose length product was 30.8 mGy*cm [IQR, 28.9–32.7] and median duration of apnea was 8.27 s [IQR, 7.69–8.85]. The sensitivity of the ultra-low dose CT was 91.2% and that of the full dose was 94%.

Conclusion

A 90% reduction in estimated dose and 38% reduction in apnea duration could be achieved using an ultra-low dose CT chest protocol on a 16-row MDCT without significant loss in the sensitivity of CT to detect COVID-related parenchymal involvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In December 2019, the new coronavirus strain (SARS-Cov-2) was first reported in Wuhan, China [1]. The virus has spread rapidly across continents and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 12, 2020 [2]. In an effort to mitigate the spread of SARS-COV-2, the medical community has relied heavily on early viral detection and patient isolation. Biological testing using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) has been the standard method of reference for diagnosis. The accuracy and predictive value of these tests may vary depending on the clinical setting, and specimen site [3]. They appear to be highly specific but may have a false negative rate in 10–40% of patients with COVID-19 [4].

Similar to many areas of the world, the laboratory of Bshary Governmental Hospital lacked RT-PCR facilities, and the performed nasopharyngeal swab consisted of limited number of specimens that were weekly sent to a central laboratory with delays in results [5]. This delay hindered a timely management and patient’s triage. CT scan emerged as a useful tool for early diagnosis of COVID-19 as reported in papers published soon after the start of the pandemic [6,7,8]. Unenhanced chest CT was performed on a Neusoft Classic CT scan with standard protocol detailed in Table 1. Clinicians relied on chest CT in addition to RT-PCR and rapid antigen tests in the triage and management of patients as reported by several institutions [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Following data from pilot studies demonstrating the high accuracy of ultra-low dose CT (LDCT) in COVID-19 diagnosis, and in application of the As Low As Reasonably Achievable (ALARA) principle [6, 8, 10, 13, 19, 20], a LDCT chest protocol was implemented as of December 2020 to achieve an estimated dose inferior to 1 millisievert.

This paper aims to share our experience of reducing radiation dose in COVID-19 patients by using an ultra-low dose CT chest protocol on a 16 row multidetector CT scan in a hospital with limited resources.

Materials and methods

This is a single center secondary retrospective analysis of prospectively acquired data approved by the hospital institutional board committee in Bshary Governmental Hospital, located in a mountainous area in the district of Bshary in North Lebanon.

Population

From April 1st, 2020, to March 31st, 2021, all patients with clinical suspicion for COVID-19 infection who underwent a CT scan of the chest in the radiology department at our institution (N = 463) were included in this study. Indication for imaging included an initial evaluation for suspected COVID-19 infection or evaluation for pulmonary involvement. Nasopharyngeal swabs for COVID-19 performed within 7 days of the CT, either before or after, was available for 168 patients (36.3%). RT-PCR was obtained for 54 patients and Rapid Antigen test (Roche) for 114 patients with a mean duration of 2.17 days ± 2.25 SD between CT and biological testing.

The duration of symptoms was clearly documented for 63 patients (13.6%) with a median of 5 days [IQR: 3–7] from symptom onset to CT.

CT protocol

The radiology department at Bshary Governmental Hospital is equipped with a Neusoft Classic 16-detector CT scan (NeuViz, China). The regular full dose CT (FDCT) chest protocol is performed with the following parameters: 120 Kilovolts (KV), automatic current modulation (O-Dose), pitch of 1 and a scan coverage area from above the lung apices to below the pleural cul-de sac. The scan duration average is ~ 15 s. Image reconstruction is carried out using an iterative reconstruction algorithm provided by the manufacturer (ClearView). Two sets of images are obtained: 1.25 mm contiguous images in a sharp kernel (Lung) and 3 mm contiguous images in a smooth kernel (Mediastinum).

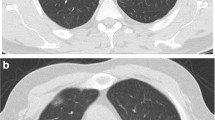

The ultra-low dose protocol was performed using the following parameters: tube kilovoltage: 80 kV, a fixed tube current ranging between 15 and 50 Milliampere-seconds (mAs) according to body habitus, as estimated by the technologist. Pitch of 1.5 and rotation speed of 0.78 s were used. The scan coverage area was limited to lung fields. Image reconstruction was carried out using an iterative reconstruction algorithm provided by the manufacturer (ClearView). Two sets of images were obtained: 3 mm contiguous images in a sharp kernel (Lung) and 3 mm contiguous images in a smooth kernel (Mediastinum). The 3 mm image thickness was used instead of 1.5 mm in order to compensate for the increase in image noise related to the low dose protocol. This compromise in image quality is accepted in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, since the analysis is focused on the lung parenchyma at the expense of a decreased image quality of the mediastinum, upper abdomen, and bones. In addition, the pitch has been increased while the scan coverage has been decreased and performed in a caudo-cranial acquisition. These modifications decreased the acquisition time and therefore the respiratory artifacts. The trade-off is a decrease in lung interstitial visibility and micronodules conspicuity.

Image analysis

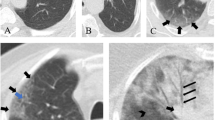

CT images were prospectively interpreted by one of two radiologists with 2 and 5 years of experience, taking into consideration the available clinical information and the result of the nasopharyngeal swab if available at the time of CT interpretation (N = 71). Signs of COVID-19 infection included ground glass opacities in a multifocal peripheral distribution, crazy paving, vascular dilation, subpleural bands and consolidations (Fig. 1) [7, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. A semi-quantitative evaluation of parenchymal involvement was also performed. A categorical assessment scheme was used to conclude the study regarding the probability of COVID-19 infection as follows: 1: normal exam, 2: other infection is more likely, 3: indeterminate for COVID-19, moderate probability, 4: highly suggestive of COVID-19, 5: typical findings for COVID. In this paper, scores ≥ 3 were considered positive for COVID-19 [31].

Data acquisition

Investigators who were blinded to the patient’s group (full or low dose CT) reviewed all medical charts, laboratory data, and biological test results of the patients. We also extracted chest CT dose summary sheets, scanning protocols, and the acquisition parameters: KV, mAs, Pitch, Rotation speed, breath hold duration, DLP and volume CT dose index (CTDIvol). The estimated effective dose was calculated by multiplying the DLP by a conversion factor (K = 0.014 for the chest) [32].

Data analysis

A threshold of 1 millisievert was used to divide our population in two groups. There were 269 regular CT exams with a full dose (FDCT; estimated dose ≥ 1 millisievert) and 194 exams with an ultra-low dose CT (LDCT; estimated dose < 1 millisievert). The biological test (RT-PCR or Rapid Antigen test) was considered our reference standard for the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was described as continuous variables expressed as median (25th-75th percentile) and categorical variables represented as number (percentage) of participants. Normality of the distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Mann–Whitney U test and Fisher Exact test were used to compare the median and percentages, respectively. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Population characteristics

The demographic data of the FDCT group (N = 269) and the LDCT group (N = 194) are summarized in Table 2. Biological tests were positive in 130/168 (77.4%) patients. CT scan was positive (score ≥ 3) in 305/463 patients (65.9%). Using a semi-quantitative visual evaluation, 34% had < 10% parenchymal involvement, 30% had 11–25%, 21% had 26–50%, 12% had 51–75% and 3% had > 75% parenchymal involvement [33].

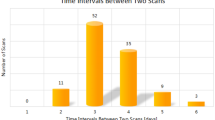

DLP and duration of apnea

The median DLP was higher 341.1 mGy*cm [IQR, 239.1–443.2] in the FDCT group compared to the LDCT group 30.8 mGy*cm [IQR, 28.9–32.7]. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.0001).

The median duration of apnea was 13.29 s [IQR, 10.85–15.73] for the FDCT group and 8.27 s [IQR, 7.69–8.85] for the LDCT group. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.0001).

Accuracy of CT compared to biological tests: RT-PCR and rapid antigen test

In the FDCT group, sensitivity for CT to detect COVID-19 was 94% when compared to biological tests, with a specificity of 63.2%. In the LDCT group, sensitivity for CT to detect COVID-19 was 91.2% with a specificity of 36.8%. A separate subgroup analysis for patients who underwent either rt-PCR or rapid antigen testing is represented in Table 3.

Discussion

The current study demonstrated that performing an ultra-low dose CT chest for COVID-19 patients on a 16-row multidetector CT scan was feasible, enabled a 90% reduction in estimated dose and 38% in apnea duration. The average DLP in our study was higher than the results described by Kang et al. [7] (14.5 mGy-cm) and Agostini et al. [19] (19.5 mGy-cm). However, they were much lower than the dose of a standard chest CT-scan protocol DLP (129.1 mGy-cm) and effective dose (1.81 mSv) [6]. Furthermore, our numbers were in the same range of the values of 1 mSv reported by Homayounieh et al. in a 54 medical institutions survey for COVID-19 CT-scans [20].

We found that both LDCT and FDCT are highly sensitive tests for the detection of COVID-19 infection, however the specificity varied significantly being moderate for FDCT and poor for LDCT. Our findings are consistent with the data reported previously by Fang et al. [12], but contrast with a subsequent study by Dagnis et al. that showed LDCT to have a much higher specificity [10]. The discrepancy may be related to the difference in accuracy of the biological tests used. A high false negative rate of CT in the early phase of the disease has been demonstrated [8, 34]. On the other hand, the sensitivity could be overestimated and the specificity compromised because of the high pre-test likelihood of having COVID-19 during the pandemic [35]. Furthermore, the biological tests represent an imperfect reference standard with reports of sensitivity around 70% for rt-PCR [12, 16, 36, 37]. This suggests that the false positive rate of Chest CT may be lower than reported. However, a consensus standard of reference including both techniques has not been performed.

This study has several limitations. First, we acknowledge the inherit selection bias of a retrospective study. Second, our study was performed in a single institution with limited resources, having a 16-row multidetector CT. More resourceful institutions that use higher generation CT scanners with very short acquisition times, newer detector technology with iterative reconstructions or AI-based algorithms may obtain further significant reduction of the radiation dose in a very short time [7, 19, 38, 39]. Third, the CT reading was performed by one of the two radiologists who were not always blinded to the biological study result and interobserver variability was not assessed. Fourth, the standard of reference is heterogeneous including antigen testing and rt-PCR, as the latter was not always available. As mentioned earlier both tests are imperfect reference standard [11, 12, 16, 36]. Fifth, the study design did not enable an assessment of diagnostic performance of LDCT in comparison to FDCT, which necessitates a simultaneous acquisition of both techniques for all the patients. However, in this study, the sensitivity of LDCT was comparable to previous studies [10, 12]. Lastly, no correlation was performed between CT findings and the clinical severity or patient’s outcome.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our data show that the implementation of a LDCT protocol on a 16-row MDCT achieved a 90% reduction of estimated dose and a 38% reduction in apnea duration without compromising diagnostic accuracy. This has a potential impact on patient triage and management, especially young patients and for those who need repetitive follow-up. Further studies are needed to address the false negative rate of LDCT compared to FDCT.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials as well as in the internal PACS of the hospital.

Abbreviations

- FDCT:

-

Full dose CT

- LDCT:

-

Ultra-low dose CT

- DLP:

-

Dose length product

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- ALARA:

-

As low as reasonably achievable

- KV:

-

Kilovolts

- mAs:

-

Milliampere-seconds

- CTDIvol :

-

CT dose index

References

Organization WH. Pneumonia of unknown cause, China; 2020.

Organization WH. WHO announces COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic; 2020.

Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, Lu R, Han K, Wu G et al (2020) Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA 323(18):1843–1844

Weissleder R, Lee H, Ko J, Pittet MJ (2020) COVID-19 diagnostics in context. Sci Transl Med 12(546):1931

Elicker BM. What is the performance and role of CT in suspected COVID-19 infection? Radiological Society of North America; 2021.

Lee C. Managing radiation dose from chest CT in patients with COVID-19. Radiological Society of North America; 2021.

Kang Z, Li X, Zhou S (2020) Recommendation of low-dose CT in the detection and management of COVID-2019. Springer, New York

Sendur HN (2021) Adherence to ALARA principle in the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Diagn Interv Radiol 27(1):154–155

Güneyli S, Atçeken Z, Doğan H, Altınmakas E, Atasoy KÇ (2020) Radiological approach to COVID-19 pneumonia with an emphasis on chest CT. Diagn Interv Radiol 26(4):323

Dangis A, Gieraerts C, Bruecker YD, Janssen L, Valgaeren H, Obbels D et al (2020) Accuracy and reproducibility of low-dose submillisievert chest CT for the diagnosis of COVID-19. Radiol Cardiothor Imaging 2(2):e200196

Xie X, Zhong Z, Zhao W, Zheng C, Wang F, Liu J (2020) Chest CT for typical 2019-nCoV pneumonia: relationship to negative RT-PCR testing. Radiology 296:200343

Fang Y, Zhang H, Xie J, Lin M, Ying L, Pang P et al (2020) Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology 296(2):E115–E117

Hamper CM, Fleckenstein FN, Büttner L, Hamm B, Thieme N, Thiess H-M et al (2020) Submillisievert chest CT in patients with COVID-19-experiences of a German Level-I center. Eur J Radiol Open 7:100283

Zu ZY, Jiang MD, Xu PP, Chen W, Ni QQ, Lu GM et al (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a perspective from China. Radiology 296(2):E15–E25

Kwee TC, Kwee RM (2020) Chest CT in COVID-19: what the radiologist needs to know. Radiographics 40(7):1848–1865

Ching L, Chang SP, Nerurkar VR (2020) COVID-19 special column: principles behind the technology for detecting SARS-CoV-2, the cause of COVID-19. Hawai’i J Health Soc Welfare 79(5):136

Herpe G, Lederlin M, Naudin M, Ohana M, Chaumoitre K, Gregory J et al (2021) Efficacy of chest CT for COVID-19 pneumonia diagnosis in France. Radiology 298(2):E81–E87

Schalekamp S, Bleeker-Rovers CP, Beenen LF, QuarlesvanUfford HM, Gietema HA, Stöger JL et al (2021) Chest CT in the emergency department for diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia: Dutch experience. Radiology 298(2):E98–E106

Agostini A, Floridi C, Borgheresi A, Badaloni M, Pirani PE, Terilli F et al (2020) Proposal of a low-dose, long-pitch, dual-source chest CT protocol on third-generation dual-source CT using a tin filter for spectral shaping at 100 kVp for CoronaVirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients: a feasibility study. Radiol Med (Torino) 125(4):365–373

Homayounieh F, Holmberg O, Umairi RA, Aly S, Basevičius A, Costa PR et al (2021) Variations in CT utilization, protocols, and radiation doses in COVID-19 pneumonia: results from 28 countries in the IAEA study. Radiology 298(3):E141–E151

Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M, Yang Y, Fayad ZA, Zhang N, et al. Chest CT findings in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): relationship to duration of infection. Radiology. 2020:200463.

Chen A, Huang J-X, Liao Y, Liu Z, Chen D, Yang C et al (2020) Differences in clinical and imaging presentation of pediatric patients with COVID-19 in comparison with adults. Radiol Cardiothor Imaging 2(2):e200117

Chung M, Bernheim A, Mei X, Zhang N, Huang M, Zeng X et al (2020) CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Radiology 295(1):202–207

El Homsi M, Chung M, Bernheim A, Jacobi A, King MJ, Lewis S et al (2020) Review of chest CT manifestations of COVID-19 infection. Eur J Radiol Open 7:100239

Guan W-J, Ni Z-Y, Hu Y, Liang W-H, Ou C-Q, He J-X et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. New Engl J Med 382(18):1708–1720

Jajodia A, Ebner L, Heidinger B, Chaturvedi A, Prosch H (2020) Imaging in corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—a scoping review. Eur J Radiol Open 7:100237

Lomoro P, Verde F, Zerboni F, Simonetti I, Borghi C, Fachinetti C et al (2020) COVID-19 pneumonia manifestations at the admission on chest ultrasound, radiographs, and CT: single-center study and comprehensive radiologic literature review. Eur J Radiol Open 7:100231

Song F, Shi N, Shan F, Zhang Z, Shen J, Lu H et al (2020) Emerging 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. Radiology 295(1):210–217

Wang J, Liu J, Wang Y, Liu W, Chen X, Sun C et al (2020) Dynamic changes of chest CT imaging in patients with COVID-19. J Zhejiang Univ (Medical Sciences) 49(2):191–197

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y et al (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395(10223):497–506

Prokop M, Van Everdingen W, van Rees Vellinga T, Quarles van Ufford H, Stöger L, Beenen L et al (2020) CO-RADS: a categorical CT assessment scheme for patients suspected of having COVID-19—definition and evaluation. Radiology 296(2):E97–E104

Christner JA, Kofler JM, McCollough CH (2010) Estimating effective dose for CT using dose–length product compared with using organ doses: consequences of adopting International Commission on Radiological Protection Publication 103 or dual-energy scanning. Am J Roentgenol 194(4):881–889

Li K, Fang Y, Li W, Pan C, Qin P, Zhong Y et al (2020) CT image visual quantitative evaluation and clinical classification of coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Eur Radiol 30(8):4407–4416

Blažić I, Brkljačić B, Frija G (2021) The use of imaging in COVID-19—results of a global survey by the International Society of Radiology. Eur Radiol 31(3):1185–1193

Raptis CA, Hammer MM, Short RG, Shah A, Bhalla S, Bierhals AJ et al (2020) Chest CT and coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a critical review of the literature to date. Am J Roentgenol 215(4):839–842

Gu J, Yang L, Li T, Liu Y, Zhang J, Ning K et al (2021) Temporal relationship between serial RT-PCR results and serial chest CT imaging, and serial CT changes in coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: a descriptive study of 155 cases in China. Eur Radiol 31(3):1175–1184

Xie X, Zhong Z, Zhao W, Zheng C, Wang F, Liu J (2020) Chest CT for typical coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: relationship to negative RT-PCR testing. Radiology 296(2):E41–E45

Macri F, Greffier J, Pereira F, Mandoul C, Khasanova E, Gualdi G et al (2016) Ultra-low-dose chest CT with iterative reconstruction does not alter anatomical image quality. Diagn Interv Imaging 97(11):1131–1140

Baker ME, Dong F, Primak A, Obuchowski NA, Einstein D, Gandhi N et al (2012) Contrast-to-noise ratio and low-contrast object resolution on full-and low-dose MDCT: SAFIRE versus filtered back projection in a low-contrast object phantom and in the liver. Am J Roentgenol 199(1):8–18

Acknowledgements

The manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors, the requirements for authorship have been met, and each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: CM, ST. Administrative support: DS, EL. Provision of study materials or patients: CM, ST, DS, SG, EL, KM, NS. Collection and assembly of data: CM, ST, DS, SG, EL, KM, NS. Data analysis and interpretation: CM, ST, WM. Manuscript writing: All authors. Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Guarantor: CM, ST, WM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approved by the hospital institutional board committee in Bshary Governmental Hospital. The IRB has approved to waive the documentation of consent (the secondary analysis of existing data).

Competing interests

None to be declared by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tawk, S., Mansour, W., Sleiman, D. et al. Submillisievert CT chest for COVID-19 patients in a rural hospital with limited resources. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 53, 61 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-022-00737-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-022-00737-9